Abstract

Measurement of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) is a non-invasive technique for studying protein dynamics in real time in living cells. FRAP studies are carried out on proteins tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) or one of its spectral variants. Illumination with high intensity laser light irreversibly bleaches the GFP fluorescence but has no effect on protein function. By photobleaching a limited region of the cytoplasm, the rate of fluorescence recovery provides a measure of the rate of protein diffusion. A detailed description of the FRAP technique is given, including its application to measuring the mobility of GFP-tagged Sup35p in [psi−] and [PSI+] cells.

Keywords: FRAP, Diffusion, GFP, Prion, Yeast

1. Introduction

The last decade has seen a revolution in the use of fluorescent microscopy in living cells brought about by the ability to express proteins with fluorescent tags. The most commonly used fluorescent tag is the green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea Victoria [1]. Development of variants of this protein with different spectral properties has enabled multiple proteins tagged with bright fluorescent signals to be imaged simultaneously [2]. There have been numerous applications of this technology for studying such diverse phenomena as protein diffusion, protein–protein interactions, and protein dynamics in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, as well as whole organisms including Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila, and mice. To achieve optimal imaging for a given sample a variety of different microscopes have been used. The total internal reflectance microscope images the basolateral surface with depth of field of about 100 nm, the confocal microscope images a section from one to several microns, and the wide-field microscope images the whole visual field.

One specific use of GFP fusion proteins is to study protein dynamics by determining the rate and magnitude of GFP fluorescence using the method of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) [3–5]. GFP produces bright, stable fluorescence that does not fade in low intensity light but is irreversibly bleached by high intensity light under conditions in which there is no significant damage of the protein fused to GFP. Thus the movement of non-bleached molecules into a bleached area can be monitored over time. If a GFP-tagged protein is reversibly bound to an immobilized structure, the rate of fluorescence recovery is typically determined by the dissociation rate of the protein rather than its rate of rebinding because the latter rate is usually only diffusion limited and is therefore much faster than the dissociation rate. On the other hand, if the GFP-tagged protein is diffusing freely in the cytosol or in a membrane, the time course and extent of fluorescence recovery provides information about the fraction of freely mobile protein and its rate of diffusion. The rate of fluorescence recovery of cytosolic proteins and membrane-bound proteins is governed by three-dimensional diffusion and lateral diffusion, respectively.

The confocal laser scanning microscope is suited for FRAP studies because it provides control over the region of illumination. This is achieved by use of the confocal pinhole which limits the amount of photobleaching in the lateral plane along the optical axis by removing out-of-focus fluorescence. Even with the pinhole, the conventional one-photon confocal fluorescence microscope accurately bleaches a defined area only in two-dimensional space [6,7]. Since the three-dimensional volume of the photobleached area is not well defined, the usefulness of this microscope in determining the true diffusion coefficient of a freely diffusible molecule is limited. Photobleaching in three-dimensional space can be achieved with much greater accuracy by using a two-photon or multi-photon fluorescence microscope because fluorophore excitation occurs only at the focal point of the microscope. This provides a well-defined three-dimensional photobleach volume and, provided that bleaching is done on a very-fast time scale, allows a true diffusion constant of the fluorophore to be measured in solution [7]. This methodology has also been applied to measuring the diffusion constants of GFP-tagged proteins in the cell, but in this case it is necessary to correct for anomalous diffusion due to transient binding to the immobile cytoplasmic matrix or to less mobile cytoplasmic proteins. Another technique for measuring diffusion coefficients is fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. This method, which measures fluctuations in fluorescence caused by diffusion of excited fluorophores in and out of a defined volume, is especially well-suited for rapidly diffusing molecules.

Even though a single-photon confocal microscope is limited in providing true diffusion coefficients, it can be used to measure relative diffusion coefficients of cytosolic proteins provided that identical photobleach settings are used when comparing either different GFP-fusion proteins or the same protein under different conditions. Therefore, even though the time course of the fluorescence recovery is not a single exponential, the half-life of the fluorescence recovery can be calculated to give a relative measure of the diffusion constant. Such an analysis has recently been applied to freely diffusing cytosolic proteins in both yeast and mammalian tissue culture cells [8–11].

FRAP has recently been used to study the mobility of the yeast cytosolic prion protein Sup35p by expressing a full-length construct of this protein fused to GFP. The relative diffusion of this construct in the non-prion and prion forms was measured in [psi−] and [PSI+] cells, respectively [8]. This article describes in detail the methodology for performing these experiments, which complement biochemical methods such as sedimentation and size chromatography to distinguish between soluble and aggregated material.

2. Experimental method

2.1. GFP-constructs of prion protein

To use FRAP to measure diffusion of prion proteins, constructs of prion proteins have to be tagged with GFP. It is necessary to insure that the GFP-tagging of the protein does not alter its functional properties. In the case of prion proteins, this means that in addition to the native conformation having normal physiological activity, it must also undergo conversion to the prion form of the protein that is able to self-propagate. Since the level of expression is important in prion biogenesis, it is best to use the endogenous promoter to express the protein. Such functional constructs of GFP-tagged prion proteins have been made for Ure2p and Sup35p. With Sup35p, the functional GFP protein (referred to as NGMC) was made by introducing the GFP between the N-terminal and middle domains of Sup35p [8]. Note that the fluorescence signal of the GFP-tagged proteins must be sufficiently bright to allow photobleaching.

2.2. Sample preparation

Several small colonies of yeast cells expressing the GFP-tagged prion protein, which were freshly plated on 1/2YPD medium (0.5% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose), are put in 10 ml of synthetic medium (SD, 0.7% yeast nitrogen base, 2% glucose) with CSM (complete supplement mixture, Q-BIOgene). The cells are grown overnight at 30 °C with 200 rpm shaking. The absorbance of the cells is measured at 600 nm the following morning, followed by dilution of the cells in 5 ml of medium to an absorbance of 0.1. The yeast cultures are maintained in log phase (absorbance less than 1 at OD600) by periodic dilution with fresh medium until the imaging experiments are performed. Unlike 1/2YPD medium, SD medium has no auto-fluorescence and is therefore suitable for imaging live cells by fluorescence microscopy.

A chamber slide (e.g. Lab-Tek chamber slide) is prepared by first coating the bottom with a 2 mg/ml solution of concanavalin A (Sigma C-5275) for 10 min. The chamber is dried by airflow in the hood, followed by washing with distilled water, and then redrying. An aliquot of cells is then added to the chamber and after 5 min the unbound cells are removed by gentle washing with medium.

2.3. Description of FRAP

Conditions have to be optimized for the specific sample that is to be photobleached; very different bleach conditions and times of image acquisition are used when measuring a freely mobile protein as opposed to a protein bound to an immobilized structure such as chromatin or Golgi. In experiments designed to examine the diffusion of cytosolic GFP-proteins, images have to be collected on a fast time scale to measure the half-life of fluorescence recovery. When photobleaching cells, it is important to optimize the settings to minimize photobleaching damage, to acquire images rapidly, and to achieve at least 50% photobleaching of the given area in order to accurately measure the time course of fluorescence recovery.

To minimize damage of the proteins by photobleaching the 488 nm line of an argon laser, which is used for both scanning and photobleaching, is adjusted to very low power level (2% output). The fluorescence intensity of the cell is adjusted electronically by raising the gain level so that the prebleach intensity is just below the saturation level of the photomultiplier tube. This increases the sensitivity of the FRAP by maximizing the range of the linear fluorescence scale. Setting the gain is best achieved by using the gray scale to image the cells; this changes the green color to shades of grayish-white unless the photomultiplier is saturated in which case the pixels are red. The gain should be adjusted so that only a few red pixels are present in the image. The pinhole setting is another variable that can be used to increase the signal. Increasing the pinhole increases the fluorescence signal since a thicker section of the cell is imaged. It is important to note that it is not possible to obtain a reasonable level of photobleaching if the sample is too dim compared to the background fluorescence of the cell. In addition, in FRAP experiments we routinely use the 40× 1.4 NA objective, rather than an objective with greater magnification (e.g. 63× or 100×), to reduce illumination and photobleaching of the sample. The zoom adjustment is used to increase the magnification of the cells.

Photobleaching of cytosolic proteins requires rapid acquisition of images in order to detect the rapid rate of fluorescence recovery that generally occurs with free GFP-tagged proteins in the cytosol. Faster data acquisition can be achieved by scanning along a smaller distance on the ordinate axis which allows rapid imaging without sacrificing resolution. A further increase in speed of acquisition can be obtained by reducing the total pixels on the screen from 512 × 512, as is routinely used, to 128 × 128. Scan speed is also a variable and is generally set for fast scanning with no number averaging of images. With these techniques, it is possible to get the scanning speed as fast as 5–10 frames/s. Of course, as the speed of acquisition is increased, there is a decrease in the resolution of the image. Therefore, the conditions that are used in FRAP studies are very different from those that are used just to examine the localization of the GFP-tagged protein in the cell. In the latter case, the settings are adjusted to optimize quality of image rather than speed of acquisition.

The photobleaching itself is achieved by repetitive photobleaching of the chosen region of interest, typically at 100% laser power. The number of bleaches is chosen to achieve a 50–80% decrease in fluorescence intensity. The shape of the photobleached area affects the extent of photobleaching and the speed of recovery. This is because diffusion into the photobleached area occurs while the area is still being bleached. In addition, GFP-tagged molecules diffuse in three-dimensions. If the bleached region is defined by a circle as opposed to a long narrow rectangle the rate of recovery in the former will be slower than in the latter even if the two regions have identical areas. This is because GFP molecules diffuse more slowly into the volume defined by a circle than that defined by narrow rectangle. However, due to limitations in the size of yeast cells, a long narrow rectangle does not work well as a bleach area in yeast cytosol, although it has been effectively used in the cytosol of mammalian cells [11].

In summary, the specific settings for photobleaching GFP-tagged cytosolic proteins in yeast cells are as follows for the Zeiss 510 confocal microscope; analogous settings can be used with other confocal microscopes. Photobleaches are done using a 488 nm laser with 40× 1.4 NA objective on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. The pinhole is adjusted to 3 µm, to achieve appreciable fluorescent signal. The gain is raised so that the full dynamic scale of the prebleached image is obtained, while insuring the photomultiplier tube is not saturated. A scan speed of nine and a zoom setting of six are routinely used; the latter yields a size of 0.07 µm/pixel. To increase the scanning rate, images are single scans and the ordinate axis of the scanning region is set to 18 µm (or less, if a faster rate of scanning is desired).

3. Experimental FRAP

3.1. FRAP of a completely mobile GFP-fusion protein

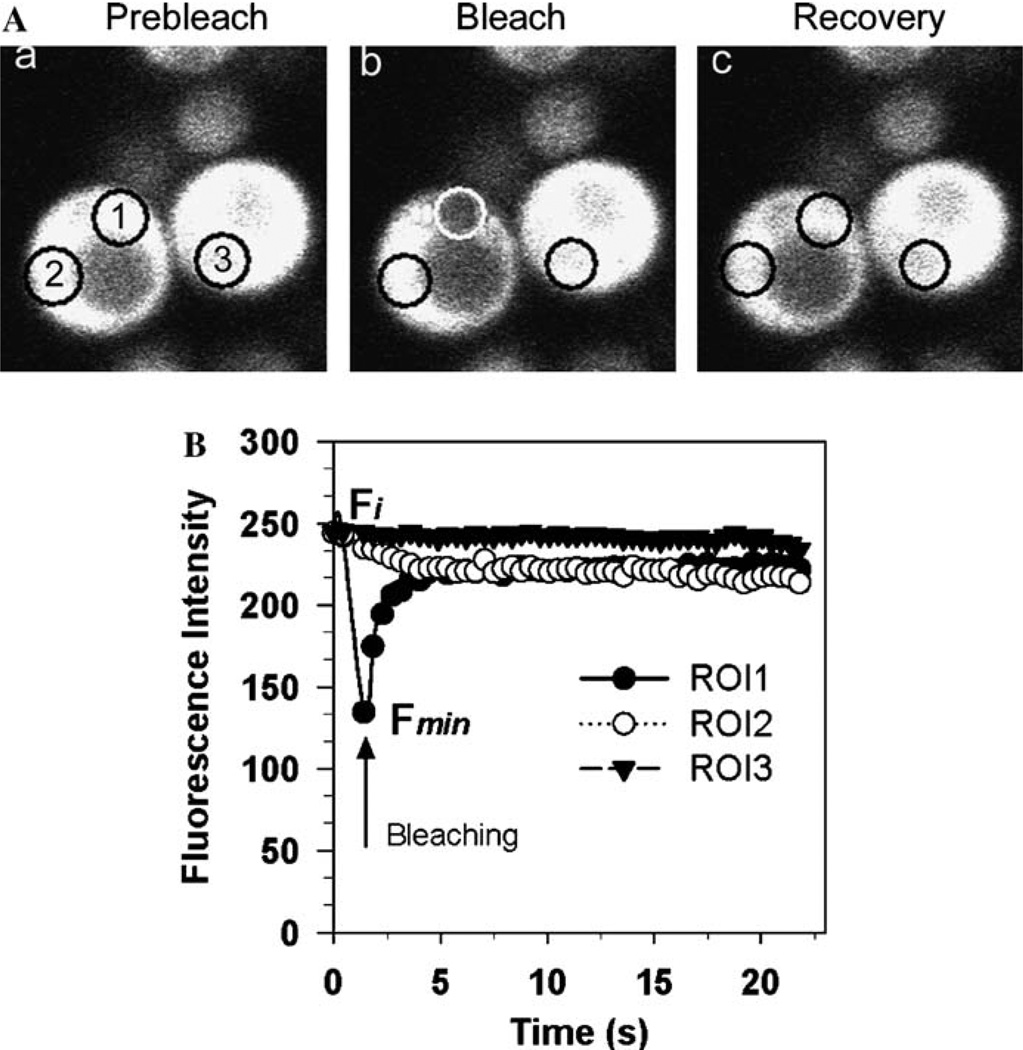

Fig. 1 shows a FRAP experiment on NGMC in [psi−] cells. The bleached region, indicated by region of interest-1 (ROI1), is a circle with a diameter of 29 pixels (~2.0 µm in diameter). ROI1 is positioned over the yeast cytosol. The cell is imaged twice at low laser intensity to obtain a prebleach value and then is rapidly photobleached 10 times at 100% laser power. Following the bleach, a series of 50 single section images are collected at low laser intensity with scan intervals of less than 0.5 s. Fig. 1A shows images of the yeast cell prior to bleaching, after bleaching, and after recovery. Two control regions are used in this bleaching experiment. ROI2, which is located in the same cell as ROI1, is a control to monitor the decrease in fluorescence intensity of the total cytosolic GFP pool due to photobleaching. Of course, ROI2 must be located in a region of the cell that has the same properties as ROI1 but it should be positioned to be minimally affected by its cytosol flowing into ROI1 during the actual bleach. ROI3, which is located in a nearby cell, is a control to monitor for photobleaching that is caused by the scanning at low level illumination.

Fig. 1.

FRAP of NGMC in [psi−] cells in yeast. (A) Cytosolic GFP-tagged protein is imaged before photobleaching (a), immediately after photobleaching (b), and 20 s after recovery (c). ROI1 is the bleached region of interest (ROI) 1. ROI2 is a control region in the bleached cell with similar fluorescence intensity as ROI1 used in correcting for the total decrease in the GFP pool. ROI3 is a control region in another cell used to determine photobleaching that occurs during the routine scanning at low laser power. The arrow indicates the time of bleaching. (B) The data obtained from the FRAP experiment in (A) are plotted as fluorescence intensity vs. function of time for the three regions. Photobleaching was performed as described in Section 2.

Fig. 1B shows the plots of the fluorescence intensity as a function of time for the three different ROIs generated using the Zeiss LSM 510 software. The ROI1 plot shows the time course of the photobleaching and fluorescence recovery. The ROI2 plot shows that the fluorescence intensity of the total cytosolic GFP pool decreased during the photobleaching of ROI1 and then remained constant during the recovery phase of the FRAP. This shows that GFP molecules are diffusing from the surrounding cytosol into the ROI1 region during the photobleach. Comparison of the ROI1 and ROI2 curves shows that the fluorescence intensity of ROI1 fully recovers when it is adjusted for the total decrease in fluorescence intensity of the cytosol. The ROI3 plot obtained in a neighboring cell is flat showing that the low intensity level scanning did not cause photobleaching.

3.2. FRAP of GFP-fusion protein with mobile and immobile fractions

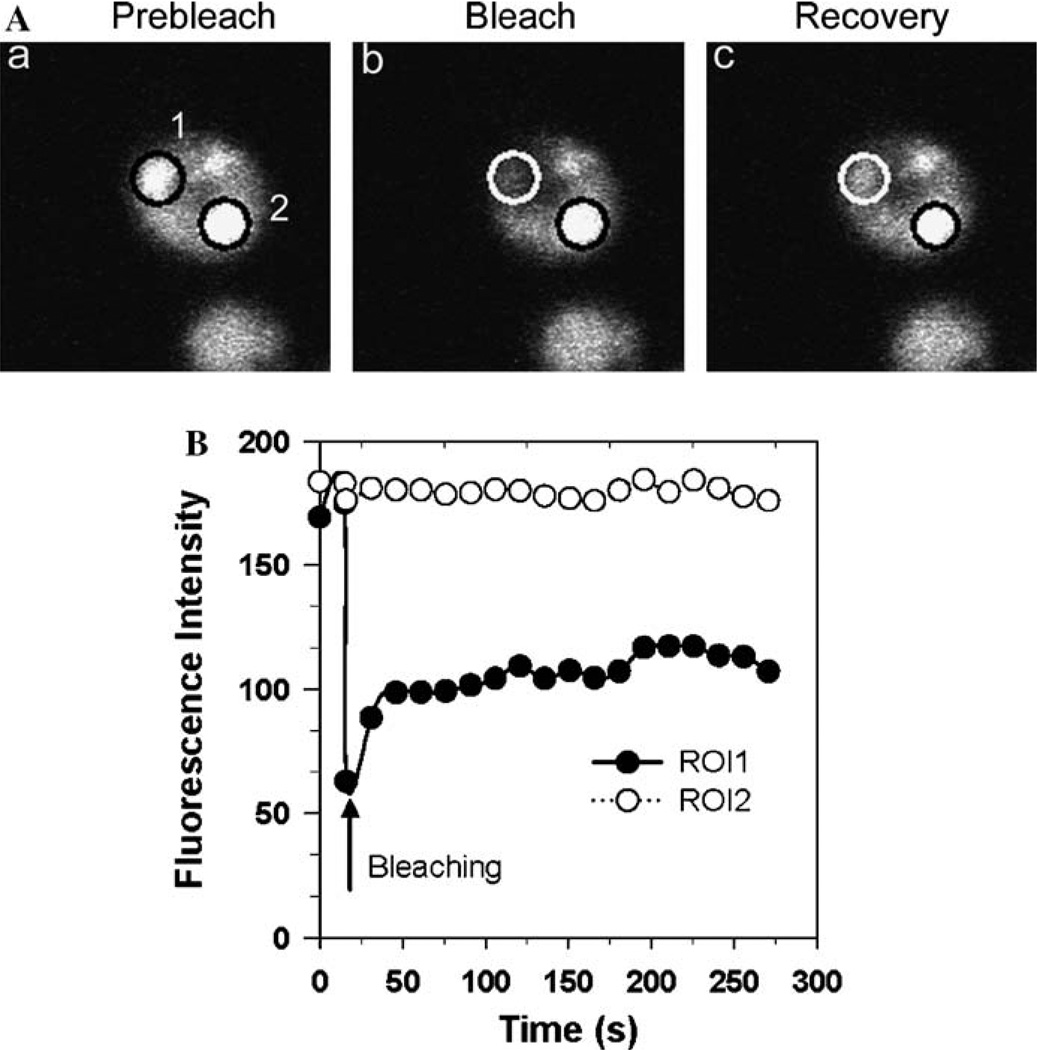

FRAP experiments can also be used to determine the mobility of GFP-tagged protein in the large protein aggregates that often occur in yeast cells. Fig. 2A shows the FRAP results obtained when an aggregate of NGMC in [PSI+] cells is photobleached in a cell containing both aggregates and free GFP-tagged protein. The results show that there is only partial recovery of ROI1 after photobleaching when ROI1 is compared to the control ROI2, which was centered in a similar aggregate in the cell that was not photobleached. To ensure that the bleached GFP-tagged protein in the aggregate is completely immobilized, the time course of recovery is followed for a much longer period of time with longer time intervals between scans than when the GFP-tagged protein is completely mobile (see above).

Fig. 2.

FRAP of NGMC in [PSI+] in yeast in late log phase. (A) Cytosolic GFP-tagged protein imaged before photobleaching (a), immediately after photobleaching (b), and 5 min after recovery (c). ROI1 and ROI2 are defined in Fig. 1. (B) The data obtained from the FRAP experiment in (A) are plotted as fluorescence intensity vs. function of time for the two regions. Note that the time scale of recovery is much slower in this figure compared to Fig. 1.

The graph of the FRAP experiment (Fig. 2B) shows that about two-thirds of the fluorescence never recovered while one third rapidly recovered. Importantly, the one-third of the fluorescence that rapidly recovered reached the same fluorescence level as the surrounding cytosol and also showed the same rate of recovery as freely diffusible GFP-tagged protein in the cytosol. Therefore, the one-third of the fluorescence that recovered is undoubtedly due to freely diffusible NGMC in the cytosol that was photobleached at the same time as the aggregate was photobleached. On the other hand, the fact that two-thirds of the fluorescence in ROI1 did not recover after 5 min when compared to the fluorescence of ROI2 suggests that the GFP-tagged protein in the aggregate was completely immobilized.

FRAP experiments are useful not only for determining the mobility of GFP-tagged proteins that are free in the cytosol or immobilized in large aggregates, but also can be used to give a quantitative measure of the amount of protein present in multiple small granules of immobilized GFP-tagged protein in the cytosol as well as the mobility of the granules themselves, which probably depends on their size. This quantitation requires the mobility of the small granules to be significantly slower than the diffusion of the freely mobile GFP-tagged protein. In this case, a biphasic fluorescence recovery curve will be observed. Of course, if most of the fluorescence is due to the granules the fluorescence recovery curve may simply appear relatively slow compared to the rapid rate that normally occurs with freely mobile GFP-tagged proteins in the cytosol.

4. Analysis of FRAP experiments

Using the fluorescence curves generated in Fig. 1B, the data can be readily exported to a spreadsheet such as Microsoft Excel to generate different plots to view the data. In Fig. 3A, the data are replotted as relative fluorescence intensity (RI) versus time using Eq. (1), where F(t)1 is the fluorescence intensity of ROI1 at time point t, and Fi1 is the initial intensity of ROI1 before bleaching.

| (1) |

Data can be plotted either with or without the correction for the fluorescence change in the control ROI2. Eq. (2), which has a correction for the ROI2 region, yields a plot of corrected relative intensity (cRI) versus time, where F(t)2 is the fluorescence intensity of ROI2 at time point t, and Fi2 is the initial fluorescence intensity of ROI2 before bleaching.

| (2) |

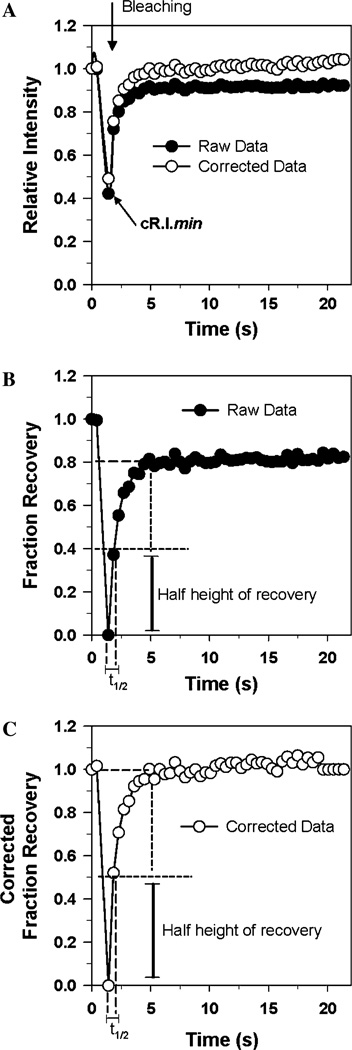

The graphs in Fig. 3A are for uncorrected (filled circles) and corrected data (open circles). The fluorescence intensity completely recovers after correction, which indicates that there is no immobilized fraction of fluorophores in the bleach region.

Fig. 3.

Creation of FRAP curves. (A) The data in Fig. 1A are plotted as relative fluorescence as a function of time using Eq. (1) for the uncorrected data and Eq. (2) for the corrected data. (B) The data in Fig. 1A are fitted as fraction of fluorescence recovery as a function of time using Eq. (3) for the uncorrected data. (C) The data in Fig. 1A are fitted as fraction of fluorescence recovery as a function of time for the uncorrected data Eq. (4) for the corrected data. The parameters used to calculate the half-life (t1/2) are shown in (B) and (C). Note that correction of the data does not significantly affect the half-life.

In Fig. 3B, the data are replotted as the fraction of recovery (FR) versus time which is useful to normalize the data. The importance of normalization is that it allows data sets obtained under identical conditions to be compiled. Specifically, for each time point, an average fraction of recovery value and its standard deviation can be calculated. Since a photobleach experiment is performed on a single cell, there is relatively high variability in the experimental data. Therefore, it is important to bleach many cells to get a representative photobleach plot with standard deviations for each time point. On the other hand, normalization obscures the extent of the initial bleach, which is why our data are processed using a spread sheet that shows plots of the relative intensity and fraction of fluorescence recovery for both corrected and uncorrected data. The relative fluorescence intensity is normalized on a zero to one scale in which the bleached intensity is equated to zero and the maximum fluorescence intensity, which is usually the prebleach intensity, is equated to one. Eq. (3) is used to normalize the data, where Fi1 is the initial intensity in ROI1 before bleaching; F(t)1 is the fluorescence intensity of ROI1 at time t; and Fmin1 is the minimum fluorescence intensity of ROI1 obtained during the experiment.

| (3) |

The above equation can then be corrected for any changes in fluorescence intensity measured in the ROI2 control region by using Eq. (4):

| (4) |

In this equation, cFR(t) is the corrected fraction of recovery, cRI(t) is the corrected relative intensity at time t and cRImin is the corrected minimum relative fluorescence intensity (obtained using Eq. (2)). Fig. 3C shows that after correcting for loss of fluorescence in the control ROI2 region, there is 100% recovery of fluorescence. As expected, the recovery curves do not fit a single exponential, but can be used to calculate the half-life of fluorescence recovery. The graphs in Fig. 3B and C show that the half-life of recovery is about 0.4 s whether or not the data are corrected. Ideally, correction should have no effect on the measured value of the half-life, but there is a small effect because the correction slightly affects the extrapolated value for maximum recovery.

5. Using FRAP to study the mobility of the yeast prion NGMC

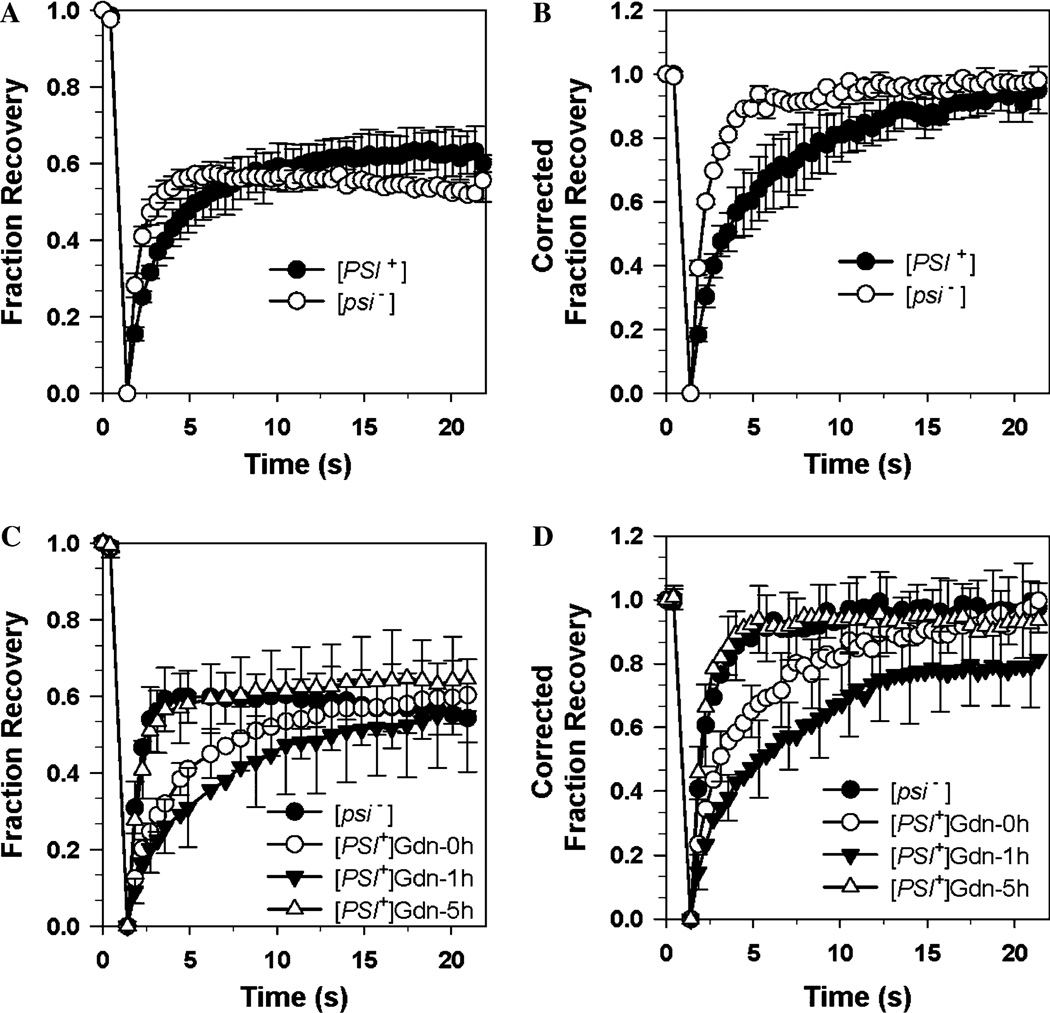

To study the Sup35p protein in both its non-prion form in [psi−] cells and its prion form in [PSI+] cells, we used yeast cells expressing the GFP-tagged Sup35p protein, NGMC. Although NGMC appeared diffuse in both [psi−] and [PSI+] cells at early log phase, FRAP measurements showed a difference in the rate of recovery in the two cell types [8]. The fluorescence recovery rate of NGMC after photobleaching was significantly slower in the prion form found in [PSI+] cells than in the non-prion form found in [psi−] cells (Fig. 4A). The extent of NGMC recovery was about 60% in both [psi−] and [PSI+] cells. Correcting the data for loss of fluorescence in the total GFP pool by using ROI2 (Eq. (4)), there is full recovery of NGMC after photobleaching (Fig. 4B). These results show that NGMC is completely mobile and photobleaching resulted in a loss of about 40% of the total GFP pool. FRAP experiments have also been used to show that the presence of the Hsp70 mutant, Ssa1-21p, slowed the recovery rate of the [PSI+] form of NGMC. In agreement with this result, column chromatography of the yeast lysate also indicated that the Hsp70 mutant caused an increase in Sup35p aggregation [8]. However, the FRAP technique has the obvious advantage of allowing observation of the prion protein in real time. Furthermore, the aggregation state of proteins might change after cell lysis.

Fig. 4.

Diffusion and dynamics of NGMC in yeast [PSI+] and [psi−] cells detected by FRAP. (A and B) FRAP of NGMC in [PSI+] and [psi−] cells was performed as described in the methods. The data are plotted as fraction fluorescence recovery versus time and are presented with no correction (Eq. (3)) and correction for ROI2 (Eq. (4)) in (A and B), respectively. (C and D) Change in dynamics of NGMC in [PSI+] cells after addition of 5 mM Gdn treatment. The data are plotted as fraction fluorescence recovery versus time and are presented with no correction (Eq. (3)) and correction for ROI2 (Eq. (4)) in (C and D), respectively. Data were obtained using 15–20 cells for each FRAP experiment. The average and standard deviation for each time point was calculated. (A and C) Reprinted from [9].

Recently, the FRAP technique was used to monitor the changes in the aggregation state of NGMC in [PSI+] cells as the yeast prion was cured by addition of a low concentration of guanidine hydrochloride (Gdn). Surprisingly, addition of Gdn to [PSI+] cells in log phase caused a biphasic response in the state of aggregation of NGMC. There was an initial increase in the size of the aggregates after 1 h of Gdn treatment followed by a slower dissolution of the aggregates resulting in the disappearance of the aggregates after ~5–6 h [9]. This biphasic response is clearly reflected in the fluorescence recovery rate in the FRAP experiment shown in Fig. 4C. During the first hour of incubation with Gdn, the rate of fluorescence recovery rate significantly decreased but then, with increasing time, this rate increased. Fig. 4D shows these same data after correcting for ROI2. In contrast to the uncorrected data, the corrected data show that the [PSI+] recovery curve obtained after 1 h of Gdn treatment does not fully recover in 20 s. The plot is still rising and it would be necessary to collect data for a longer time interval to calculate an accurate half-life and to determine whether there is an immobilized fraction in our population. Just by imaging of [PSI+] cells upon addition of Gdn, we also observed a biphasic change in the aggregation state of NGMC. Specifically, there was the appearance and dissolution of granules during the 5 h incubation period with Gdn. However, unlike FRAP, imaging alone cannot be used to quantify the extent of aggregation.

Interestingly, the FRAP experiments (Fig. 4C and D) showed that after 5 h in Gdn, the recovery rate of NGMC was identical in [psi−] and [PSI+] cells. When we plated the [PSI+] cells after 5 h in Gdn, the resulting colonies were [PSI+], which suggested there were still prion aggregates present in the cells but the amount or size of these aggregates had become too low to detect by FRAP. This observation that Gdn significantly reduced NGMC aggregation in both mother and daughter cells led us to examine whether over a longer period of time, Gdn could cure [PSI+] cells without cell division occurring. In fact, we found that this was indeed the case when we determined that the rate of curing upon addition of Gdn was not significantly affected by inhibiting cell division with α-factor [9]. Therefore, by using FRAP to examine aggregation states of [PSI+] in yeast, we have obtained important insights into the mechanism of prion curing by Gdn.

6. Concluding remarks

The use of FRAP on GFP- tagged cytosolic proteins provides a measure of the mobility of these proteins in cells. In addition to measuring the diffusion of the GFP-tagged prion protein Sup35p in [PSI+] and [psi−] cells, this methodology can be applied to other GFP-tagged proteins including Huntingtin fragments which have been expressed in yeast [12] and other yeast prions. Already, functional GFP-fusion proteins have been made such as Ure2-GFP and Rnq1-GFP [13,14], proteins which are known to exist in both non-prion and prion forms. In conclusion, the major advantage of FRAP is that it is a non-invasive method of examining the diffusional mobility of proteins in real time in the living cell. Thus, it complements biochemical methods using yeast lysates that have been used to measure the extent of aggregation of prion proteins in yeast.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Xufeng Wu for technical assistance in optimizing FRAP conditions and Dr. Ben Glick for technical advice in preparation of yeast cells for microscopy.

References

- 1.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, Campbell RE, Ting AY, Tsien RY. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:906–918. doi: 10.1038/nrm976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reits EA, Neefjes JJ. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:E145–E147. doi: 10.1038/35078615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Altan-Bonnet N, Patterson GH. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003 Suppl:S7–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Snapp E, Kenworthy A. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:444–456. doi: 10.1038/35073068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coscoy S, Waharte F, Gautreau A, Martin M, Louvard D, Mangeat P, Arpin M, Amblard F. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:12813–12818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192084599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown EB, Wu ES, Zipfel W, Webb WW. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2837–2849. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77115-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song Y, Wu YX, Jung G, Tutar Y, Eisenberg E, Greene LE, Masison DC. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:289–297. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.289-297.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu YX, Greene LE, Masison DC, Eisenberg E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:12789–12894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506384102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S, Nollen EA, Kitagawa K, Bindokas VP, Morimoto RI. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:826–831. doi: 10.1038/ncb863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng XC, Bhasin S, Wu X, Lee JG, Maffi S, Nichols CJ, Lee KJ, Taylor JP, Greene LE, Eisenberg E. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:4991–5000. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krobitsch S, Lindquist S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1589–1594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edskes HK, Gray VT, Wickner RB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1498–1503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Hong JY, Liebman SW. Cell. 2001;106:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]