Abstract

Background

Pulmonary hypertension is associated with vascular remodeling and increased extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. While the contribution of ECM in vascular remodeling is well documented, the roles played by their receptors, integrins, in pulmonary hypertension have received little attention. Here we characterized the changes of integrin expression in endothelium-denuded pulmonary arteries (PAs) and aorta of chronic hypoxia as well as monocrotaline-treated rats.

Methods and Results

Immunoblot showed increased α1-, α8- and αv-integrins, and decreased α5-integrin levels in PAs of both models. β1- and β3-integrins were reduced in PAs of chronic hypoxia and monocrotaline-treated rats, respectively. Integrin expression in aorta was minimally affected. Differential expression of α1- and α5-integrins induced by chronic hypoxia was further examined. Immunostaining showed that they were expressed on the surface of PA smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), and their distribution was unaltered by chronic hypoxia. Phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase was augmented in PAs of chronic hypoxia rats, and in chronic hypoxia PASMCs cultured on the α1-ligand collagen IV. Moreover, α1-integrin binding hexapeptide GRGDTP elicited an enhanced Ca2+ response, whereas the response to α5-integrin binding peptide GRGDNP was reduced in CH-PASMCs.

Conclusion

Integrins in PASMCs are differentially regulated in pulmonary hypertension, and the dynamic integrin-ECM interactions may contribute to the vascular remodeling accompanying disease progression.

Key Words: Integrins, Chronic hypoxia, Monocrotaline, Pulmonary hypertension, Pulmonary arteries

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension is characterized by a sustained rise in the pulmonary arterial pressure that results from pulmonary vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling [1]. Pulmonary vascular remodeling involves increased pulmonary arterial cell proliferation and hypertrophy, leading to thickening of the pulmonary arterial wall. Another underlying feature of pulmonary vascular remodeling that accompanies pulmonary hypertension is an increase in the deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, particularly collagen, elastin, tenascin-C and fibronectin, which have been documented in both human and animal models of the disease [1,2,3,4]. The increased deposition of matrix proteins in the pulmonary vasculature has been attributed to increases in serine elastase activity, as well as a change in the balance of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMP) activity [5,6]. The importance of elastase/proteinase in pulmonary vascular remodeling is exemplified in animal models of pulmonary hypertension. For example, inhibition of serine elastase activity reversed pulmonary hypertension both in rats exposed to chronic hypoxia as well as monocrotaline (MCT) [5,7], while inhibition of MMPs by gene transfer of a human TIMP1 gene attenuated and aggravated vascular remodeling, respectively, in rats treated with MCT and chronic hypoxia [6]. Additionally, the specific MMP inhibitor Batimastat, which has no influence on systemic circulation, attenuated pulmonary hypertension in chronically hypoxic rats [6].

While the importance of matrix components in pulmonary vascular remodeling has been implicated extensively in the development of pulmonary hypertension, relatively little attention has been paid to the involvement of integrins, the receptors for the ECM proteins. Integrins comprise a superfamily of structurally related heterodimeric transmembrane receptors that mediate cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions. They physically bridge the ECM and the cytoskeleton, acting as transducers of ‘outside-in’ and ‘inside-out’ signaling [8]. Of the 18 α- and 8 β-subtypes that have been identified to date, α1–9, αv, β1, β3, β4 and β5 integrins have been reported in vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs), and α1–5, α7, α8, αv, β1, β3 and β4 integrins have been detected in the pulmonary vasculature [8,9,10]. Integrins play important roles in various vascular functions, including mechano-transduction, myogenic response, ECM synthesis, SMC proliferation, apoptosis and migration, neointimal formation, and eutrophic inward remodeling [9,11]. In the pulmonary vasculature, we showed that integrin-binding hexapeptides are capable of mobilizing intracellular Ca2+ in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs). We further showed that one of these peptides, namely GRGDSP, mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ from ryanodine receptor-gated organelles and lysosome-related acidic organelles, by causing an increase in cyclic ADP ribose [10]. In the context of pulmonary hypertension, the involvement of αvβ3 integrin has thus far been documented in MCT-treated rats, where the elastase-mediated activation of MMPs leads to αvβ3 integrin clustering and subsequent transcription of tenascin-C and an increase in SMC proliferative response to growth factors [1,12,13].

In this study we hypothesized that integrins are regulated concurrently with the increased deposition of ECM components observed in the development of pulmonary hypertension. To test this hypothesis, we took advantage of two different rat models of pulmonary hypertension, namely the chronic hypoxia and MCT-induced models, in order to discriminate between the direct effects of experimental treatments (that is, hypoxia or MCT) versus those related to the resultant vascular remodeling. In doing so, we systematically compared the differences in the expression of a number of α and β integrin proteins specifically in endothelium-denuded pulmonary arteries (PAs) and aorta, in contrast to previous gene expression profiling studies that have taken a global approach using mostly extracts from whole lung tissues [for review, see [14]]. We further confirmed the expression of the integrins in small PAs by immunohistochemistry, compared focal adhesion kinase (FAK) phosphorylation in PAs and PASMCs, and correlated the changes in function by monitoring the [Ca2+]i responses generated by integrin-specific peptide ligands in PASMCs of the chronic hypoxia rat model.

Materials and Methods

Chronic Hypoxia and MCT Treatment

Male Wistar rats (150–200 g) were used for all treatments. Hypoxic pulmonary hypertension was induced by exposure to normobaric hypoxia (10% O2) for 4 weeks, while normoxic controls were reared in room air for the same period of time. MCT-induced pulmonary hypertension was developed by injection with a single subcutaneous dose of MCT (60 mg/kg; Sigma). Animals were sacrificed 24 days later. All animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (130 mg/kg intraperitoneally) prior to removing the heart and lungs. Development of pulmonary hypertension was validated in both models by confirming right ventricular hypertrophy, which was done by separating the right ventricle (RV) from the left ventricle plus septum (LV+S), weighing these components and calculating the ratio of RV/(LV+S). All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines specified by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation of PAs and PASMCs

PAs were dissected and PASMCs were enzymatically isolated as previously described [15]. Briefly, lungs were removed from male Wistar rats (150–200 g) anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (130 mg/kg intraperitoneally), upon which intrapulmonary arteries of 3rd and higher generations (inner diameter approx. 0.3–1 mm) were dissected in HEPES-buffered salt solution (HBSS) containing (in mM) 130 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES and 10 glucose, pH 7.4. PAs were cut open, carefully cleaned of connective tissue, and the endothelial layer was removed by rubbing the luminal surface thoroughly with a cotton swab. Arteries were stored at −80°C for Western blot analysis. For enzymatic isolation of PASMCs, arteries were incubated in icecold HBSS (30 min), and then in reduced-Ca2+ (20 μM) HBSS (20 min, room temperature), upon which they were digested in reduced Ca2+ HBSS containing collagenase (type I, 1,750 U/ml), papain (9.5 U/ml), bovine serum albumin (2 mg/ml) and dithiothreitol (1 mM) at 37°C for 18 min. After washing with Ca2+-free HBSS, single SMCs were gently dispersed from the tissues by trituration in Ca2+-free HBSS. PASMCs were plated on 25-mm glass cover slips for Ca2+ fluorescence experiments or on 35-mm culture dishes, which were noncoated or coated with human collagen type IV or fibronectin (BD Biosciences), for determination of FAK phosphorylation. PASMCs isolated from normoxic and chronic hypoxic rats and normoxic rats were transiently cultured under normoxic condition (air + 5% CO2) or in a modular incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberg) containing 4% O2 and 5% CO2 (16–24 h, 37°C).

Preparation of Protein Samples and Immunoblot

Total protein was isolated from PAs, aorta, and cultured PASMCs for Western blot analysis of integrin expression and phosphorylation of FAK. Endothelium-denuded PAs and aorta were frozen in liquid nitrogen, pulverized and homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer (30 strokes) in ice-cold Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1 mM) and protease cocktail inhibitor (Roche). Homogenized tissues or cultured cell lysate were centrifuged (3,000 g, 4°C, 10 min), upon which the protein concentrations of the postnuclear supernatant were measured with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). Protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot. They were treated with Laemmli sample buffer with (for integrin β3) or without (for all other integrin subtypes) β-mercaptoethanol (100°C, 5 min), separated by an 8% polyacrylamide gel (5 μg per lane), and electrotransferred onto Immobilon P membranes (0.45 mm; Millipore) using a tank transfer system (80 V, 3 h, 4°C). Upon blocking (1 h, room temperature) with 5% skim milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST), membranes were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in PBST containing 3% BSA (BSA/PBST) at 4°C overnight. The following primary antibodies were used: integrin α1 (1:1,000, AB1934; Chemicon International); α5 (1:1,000, AB1949; Chemicon); α8 (1:2,500; generous gift from Dr. Lynn Schnapp, University of Washington); αv (1:250, 611012; BD Biosciences); β1 (1:2,000, AB1952; Chemicon); β3 (1:500, 4702; Cell Signaling); total FAK (1:1,000, 06-543; Millipore); phospho-FAK (1:1,000, 44-624G; Invitrogen); Actin (1:5,000, SC-1615; Santa Cruz). After washing in PBST, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-coupled donkey-anti-rabbit or sheep- anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences) diluted in 1% BSA/PBST (1 h, room temperature), and again washed extensively. Protein signal was then detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce Biotechnologies), and intensity was quantified using a Gel Logic 200 Image System (Kodak).

Immunostaining of Lung Section and PASMCs

Lung tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS (0.05 M phosphate buffer, 0.9% sodium chloride, pH 7.4), rinsed in PBS and cryoprotected with 18% sucrose in PBS (24 h, 4°C). Alternate cryostat sections (10 μm) were collected on lysine-coated slides, dried briefly, and blocked with 1% BSA and 10% normal goat serum (60 min, room temperature). For immunostaining α8 integrin, a tyramine signal amplification kit (Perkin Elmer) was used; for these sections, prior to blocking with goat serum, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with hydrogen peroxide (3 in 50% methanol in PBS, 30 min). The sections were then incubated overnight (4°C) in a rabbit antibody recognizing individual integrins (same antibodies as used for immunoblotting) and mouse monoclonal antibody recognizing smooth muscle α-actin (Abcam Inc.) diluted in PBS containing 1% BSA, 0.5% Triton X-100). Separate sections were processed similarly for negative control except the primary antibody was replaced with rabbit IgG to evaluate nonspecific staining. For tyramine signal amplification, sections were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (1 μg/ml) and then with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated tyramide (Molecular Probes) in amplification solution; otherwise, sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti-mouse conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594. Washed slides were mounted in Tris-buffered glycerol (pH 8.6).

PASMCs from normoxic and hypoxic rats were placed on poly-L-lysine (0.01% w/v in H2O; Sigma) coated 25 mm cover glass and incubated at 37°C in Ham's F-12 medium under air and 5% CO2 or 4% O2 and 5% CO2 in a modular incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberg), respectively, for 5 h. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 min and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies for integrin α1 (1:400 dilution; Chemicon AB1934) and α5 (1:100 dilution; Chemicon AB1949) in the presence of 1% normal goat serum. Cy™3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:800 dilution, 111-165-144; Jackson Immuno) was used for secondary antibody incubation for 1 h at room temperature. After mounting the cover glass, images were captured using a Carl Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Calcium Imaging

PASMCs were loaded with fluo-3 AM dissolved in DMSO containing 20% pluronic acid (10 μM) for 45 min at room temperature (Molecular Probes). Upon washing thoroughly with Tyrode solution containing (in mM) 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 D-glucose and 10 NaHEPES (pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH), the cytosolic dye was allowed to de-esterify for 20 min. Fluo-3 fluorescence of PASMCs were detected under a Nikon Diaphot microscope equipped with epifluorescence attachments and a microfluorometer (model D-104; PTI). After a stable resting [Ca2+]i was attained for more than 10 min, the integrin-specific ligands GRGDTP and GRGDNP were applied to PASMCs and the fluorescent signal was recorded for 15 min. The Ca2+ response of both normoxic and hypoxic PASMCs was examined under normoxic conditions for the comparison of integrin-dependent response in the absence of acute influence of hypoxia intracellular [Ca2+]i. Protocols were executed and data collected on-line with a Digidata analog-to-digital interface and the pClamp software package (Axon Instruments Inc.). Fluorescence intensity (F) was used to calculate the intracellular concentrations of Ca2+: [Ca2+]i = [KD· (F – Fbg)]/(Fmax – F), where Fbg is the background fluorescence and Fmax is the maximum fluorescence. Values for Fmax were determined in situ by superfusing the cells with the 10 μM Ca2+ ionophone 4-Br-A23187 (EMD Biosciences), and values for Fbg were obtained in an area devoid of cells upon Mn2+ quenching.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. The numbers of cells are specified in the text. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was assessed by paired or unpaired Student's t tests or ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post hoc analyses wherever applicable. For Western blot analysis of integrin subtypes, each sample represented protein isolated from one animal and was normalized to the average intensities of control samples within each blot. Control-normalized values were then averaged between replicate blots. FAK phosphorylation was quantified by the ratio of the phospho-FAK signal over total FAK signal for each sample. Conventional housekeeping genes, such as smooth muscle α-actin, β-actin, GAPDH and cyclophilin are regulated with hypoxia [16,17]. Immunoblot analysis of smooth muscle α-actin, and β-actin were consistently regulated in these experiments, and were therefore not used as loading controls. Instead, protein concentration was used to ensure even loading, and a large sample size was used to minimize random errors resulting from pipetting.

Results

Validation of the Rat Models of Pulmonary Hypertension

Right ventricular hypertrophy as measured by comparing the mass ratio, RV/(LV+S), was used to confirm the development of pulmonary hypertension in chronic hypoxia and MCT-treated animals. RV/(LV+S) was significantly elevated in rats exposed to 4 weeks of chronic hypoxia (normoxia: 0.276 ± 0.004, n = 48; hypoxia: 0.52 ± 0.01, n = 46, p < 0.001) and in rats 3 weeks after MCT injection (control: 0.265 ± 0.005, n = 27; MCT: 0.53 ± 0.03, n = 25, p < 0.001).

Effect of Chronic Hypoxia on Integrin Protein Levels

We investigated the effect of chronic hypoxia on selected integrin subtypes at the protein level by immunoblot analysis. Chronic hypoxia significantly elevated α8 integrin protein levels by 51.7 ± 14.9% compared to normoxic controls (p < 0.007, n = 12 animals), along with the levels of integrins α1 and αv (45.6 ± 6.4%, p < 0.001, n = 12 animals for α1; 45.1 ± 10.0%, p < 0.002, n = 15 animals for αv) (fig. 1a, b). On the other hand, integrin α5 and β1 protein levels were decreased in PAs isolated from chronically hypoxic rats (−36.6 ± 6.1%, p < 0.001, for α5; −35.5 ± 6.7%, p < 0.001, for β1; n = 15 animals each) (fig. 1a, b). In contrast to the significant changes in protein expression observed in the PA, chronic hypoxia affected integrin levels minimally in the aorta (fig. 1c, d), in which only the expression of α8 integrin was reduced to statistically significant levels by chronic hypoxia (−16.6 ± 3.5%, p < 0.001, n = 16 animals).

Fig. 1.

Representative immunoblots of integrin proteins in endothelium-denuded PA (a) and aorta (c) of rats exposed to chronic hypoxia and normoxia. Each lane represents protein isolated from an individual animal. b, d Densitometric data obtained from immunoblots (n = 12–15 animals). Twelve animals per treatment group were used to compile the data in b for α1 and α8 integrins, while 15 were used for all others. Data are normalized to the average of the normoxic controls. Asterisks show significant changes in integrin protein expression upon exposure to chronic hypoxia (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. control).

Effect of MCT Treatment on Integrin Protein Levels

To distinguish whether the changes in integrin expression were due to direct effects of hypoxia or to pulmonary vascular remodeling, we turned to the MCT model of pulmonary hypertension. As shown in figure 2a and b, the changes in integrin protein expression were more pronounced in the PAs of MCT-treated animals. α1 integrin expression was most dramatically increased, by 149 ± 36% (p = 0.004, n = 11 animals), when compared to controls. This was followed by α8 and αv integrins, which were increased by 71.4 ± 14.8% (p < 0.001, n = 11 animals) and 65.1 ± 19.5% (p = 0.006, n = 11 animals), respectively. Levels of α5 and β3 integrins were reduced in PAs isolated from MCT-treated animals by 24.7 ± 6.7% (p = 0.006, n = 11 animals) and 26.2 ± 10.8% (p = 0.034, n = 11 animals) respectively. Protein levels of integrin β1, while unaffected in PAs, were increased by 37.8 ± 13.6 % (p = 0.015, n = 11 animals) in aorta isolated from MCT-treated animals (fig. 2c, d).

Fig. 2.

Representative immunoblots of integrin proteins in endothelium-denuded PA (a) and aorta (c) of rats treated with MCT (60 mg/kg) for 24 days versus control. b, d Densitometric data obtained from immunoblots (n = 11–12 animals). Data are normalized to the average of the controls. Asterisks show significant changes in integrin protein expression upon treatment with MCT (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. control).

Detection of Integrin Expression by Immunohistochemistry

We further examined the expression of integrins in small PA in lung sections using double immunofluorescent staining. Positive signals were detected in small PAs using specific antibodies against α1, α5, α8, β1, and β3 integrins, which overlapped with the signals of smooth muscle-specific α-actin (fig. 3), indicating that they originated from SMCs of small PAs. These results are consistent with the immunoblot studies using large PAs demonstrating integrin expression in PA smooth muscle. Immunoreactivities of various integrin subtypes were also detected in cells other than smooth muscle, but their signal levels were generally higher in actin-positive cells. However, immunohistochemistry was unsuitable for quantitative comparison of integrin expression in PAs of the chronic hypoxia and MCT models due to possible variability introduced by sectional plains, size of smooth muscle layer and sample processing. Differential expression of α1 and α5 integrins was further investigated in PASMCs of chronic hypoxia rat. Confocal imaging detected clear immunoreactivity of α1 and α5 integrins in the peripherial regions of PASMCs isolated from normoxic and chronic hypoxic rats (fig. 4a, b), suggesting that the integrin proteins were expressed predominantly on the cell surface. Cell surface expression of integrin was similar in normoxic and chronic hypoxic cells. The signals for α1 integrin were generally stronger, while those for α5 integrin were weaker, in the hypoxic PASMCs when they were recorded using the same settings for confocal imaging. However, variability of immunofluorescence signals in different samples precluded quantitative comparison.

Fig. 3.

Immunostaining of integrin and smooth muscle α-actin in small PAs in lung sections of control rats. Confocal images show fluorescent signals from lung sections double-stained with a α1 (a), α5 (b), α8 (c), β1 (d) and β3 (e) integrin-specific antibody, and an α-actin-specific antibody. Transmission images show the lung structures, while the yellow color indicates the regions in which there were overlaying of signals of integrin protein and α-actin in PAs. The images were taken with a Plan Neofluar ×20 objective (numerical aperture = 0.5), pinhole size = 1 airy, and zoom was between 2.7 and 3.6. Scale bars = 20 μm (a, b); 10 μm (c–e).

Fig. 4.

Confocal images of immuno-fluorescent signals (red) of α1 (a) and α5 integrin (b) in PASMCs isolated from normoxic and chronic hypoxic rats. Transmitted light images (right panels) were included for reference. The images were taken with a Plan Neofluar ×40 oil objective (numeric aperture = 1.3), pinhole size = 1 airy, and zoom = 4. Laser power, sensitivity and gain were set at the same level for confocal imaging of the normoxic and hypoxic cells.

Effect of Chronic Hypoxia on FAK Phosphorylation in PAs and PASMCs

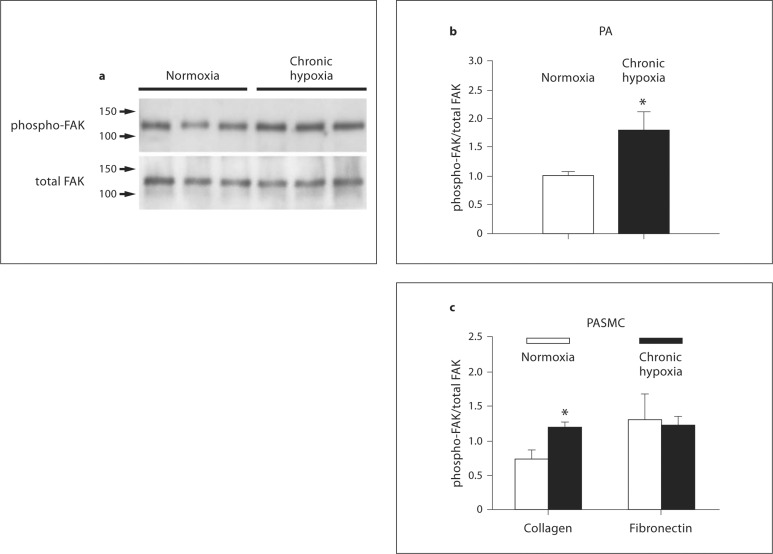

To examine if the alterations in integrin expression were evidenced in integrin-dependent signaling pathways, phosphorylation of FAK in endothelium-denuded PAs of control and chronic hypoxic rats was determined by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for phosphorylated and total FAK. The signal ratio of phosphorylated over total FAK was significantly higher (181.4 ± 29.7% of normoxic control, n = 6, p < 0.025) in the hypoxic PAs (fig. 5). FAK phosphorylation was also higher in PASMCs isolated from hypoxic rats (180.8 ± 34.0% of normoxic control, n = 4), when transiently cultured (24 h) on surfaces coated with type IV collagen, a ligand for the α1 integrin whose expression was elevated in hypoxic PASMCs (fig. 1a, b). In contrast, the differences of FAK phosphorylation between normoxic and hypoxic PASMCs disappeared when cells were cultured on fibronectin, a typical ligand for α5 integrin, whose expression was reduced by hypoxia (fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 5.

a Representative immunoblots of phosphorylated FAK and total FAK in endothelium-denuded PAs from normoxic and hypoxic animals. Each lane represents protein isolated from an individual animal. b A bar graph summarizes the averaged signal ratio of phosphorylated FAK over total FAK in PAs (n = 6 animals in each group). c The signal ratio of phosphorylated FAK over total FAK in PASMCs isolated from normoxic and hypoxic rats that were transiently cultured in culture dish coated with collagen IV or fibronectin (n = 4 experiments with cells from 4 different animals in each group). Asterisks show significant changes in increase in FAK phosphorylation upon exposure to chronic hypoxia (* p < 0.05 vs. normoxia).

RGD-Induced Calcium Signals

To test if the changes in hypoxia-induced integrin expression are translated into altered physiological function, we monitored the [Ca2+]i response to RGD peptides in PASMCs isolated from normoxic and chronic hypoxic rats. Integrin α1, whose expression was significantly upregulated upon exposure to chronic hypoxia, recognizes collagen types I and IV when dimerized with β1 integrin. We therefore compared the intracellular Ca2+ response of PASMCs to GRGDTP, which preferentially interacts with receptors for collagen, including α1β1 integrin [18].

Exogenous application of GRGDTP (1 mM) to PASMCs isolated from normoxic control rats elicited a maximum increase in [Ca2+]i of 73 ± 16 nM (fig. 6a, b; at 10 min, n = 30 dishes). When applied to PASMCs isolated from rats exposed to chronic hypoxia, GRGDTP caused [Ca2+]i changes of a larger magnitude (Δ[Ca2+]i = 114 ± 24 nM, at 3.5 min, n = 29 dishes) than in normoxic PASMCs. Moreover, the time course of the [Ca2+]i transient induced by GRGDTP was faster in the hypoxic cells, where the peak Δ[Ca2+]i was reached by 3.5 min after GRGDTP application, as opposed to 8 min in normoxic controls. At 3.5 min after GRGDTP application, the Ca2+ response observed in PASMCs isolated from chronic hypoxic rats was significantly larger than the normoxic controls (fig. 6b, p < 0.001).

Fig. 6.

[Ca2+]i transients elicited by integrin-binding peptides in PASMCs from normoxic and chronic hypoxic rats. a Time course of GRGDTP-induced [Ca2+]i response in normoxic (black squares) or chronic hypoxic (gray circles) PASMCs. n = 29 dishes of PASMCs, from 3 rats on 3 separate days. b Bar graph summarizing the peak and plateau phases of Δ[Ca2+]i at 3.5 and 10 min after application of GRGDTP. c Time course of GRGDNP-elicited [Ca2+]i response in normoxic (black squares) or chronic hypoxic (gray circles) PASMCs. n = 30 dishes of PASMCs, from 3 rats on 3 separate days. d Bar graph summarizing the peak and plateau phases of Δ[Ca2+]i at 3.5 and 13 min postapplication of GRGDNP.

To test if the decreased α5 integrin expression in the PAs of chronic hypoxic rats affected [Ca2+]i signaling, we utilized the hexapeptide GRGDNP, which predominantly targets the fibronectin receptor including α5β1 integrin [19]. GRGDNP (0.5 mM) elicited a biphasic Ca2+ response with an initial peak followed by a sustained plateau phase (fig. 6c, d). The initial response in PASMCs isolated from normoxic and chronic hypoxic rats were similar, at 153 ± 21 and 125 ± 21 nM, respectively. However, the sustained phase of the GRGDNP-induced Ca2+ response was significantly reduced in PASMCs isolated from chronic hypoxic rats (34 ± 8 nM, n = 27 dishes) as compared to those isolated from normoxic controls (79 ± 12 nM, n = 26 dishes, p = 0.003).

Discussion

The present study extends our previous report on the characterization of integrin expression and Ca2+ response in rat PA smooth muscle [10]. Immunostaining shows that integrin proteins are expressed in α-actin-positive smooth muscle layer in small PAs and localized in the surface of PASMCs. The expression of integrin proteins is altered in endothelium-denuded PAs in chronic hypoxia and MCT-induced pulmonary hypertensive rats. Both models displayed significant increases in α1, α8 and αv integrins as well as a downregulation of α5 integrin. Integrin β1 and β3 protein levels were also significantly suppressed in chronic hypoxia and MCT-treated rats, respectively. Downstream integrin signaling was also affected in congruence with the altered integrin expression, such that the levels of FAK phosphorylation were augmented in PAs of chronically hypoxic rats, and the enhanced phosphorylation was further maintained in hypoxic PASMCs when cultured on the α1 integrin ligand collagen IV. Moreover, the upregulation of α1 integrin and the downregulation of α5 integrin in chronic hypoxic PAs were correlated with increased and decreased Ca2+ mobilization in PASMCs induced by RGD peptides that specifically target these integrins. The effects of both chronic hypoxia and MCT were specific to the pulmonary vasculature, as endothelium-denuded aorta from the same animals displayed virtually no change in integrin expression, except a small reduction of α8 integrin in the hypoxic animals and a minor increase in β1 integrin in MCT treated rats. Our results therefore indicate that integrin expression and associated signaling pathways are altered in pulmonary hypertension and partake in pulmonary vascular remodeling that accompanies disease progression.

The differential regulation of integrins observed in this study underscores the complex interplay of ECM/integrin-dependent mechanisms, which depends on the temporal alterations in synthesis, deposition and reorganization of various ECM components, as well as the expression of specific integrins at different stages of disease progression. In the chronic hypoxia model, increased deposition of ECM components including collagen type I, III and IV, elastin, laminin as well as fibronectin has been reported [20,21,22,23]. Transcripts of type IV collagen increase within 6 h and decline after 10 days, whereas type I and III collagen as well as fibronectin mRNA increase after 3 days and then decline to the control level after 10 days of exposure to hypoxia [22]. Elevated levels of ECM proteins could be observed in 4 days of hypoxia and progress with time [23]. Similar increases in collagen, elastin, laminin, tenascin and fibronectin occur in the MCT model [24,25,26,27]. Elevated mRNA levels of laminin and tenascin could be detected within one day, and the increases in immunolocalizable fibonectin, laminin, perlecan and type IV collagen protein around the vasculature could be observed 4 days after MCT treatment [24,26]. ECM components continue to increase as the disease develops. The present study at 4 weeks of chronic hypoxia and 24 days of MCT treatment, therefore, is a snapshot view of the alterations in integrin expression in established pulmonary hypertension.

Amongst the integrins surveyed in this study, α1 integrin was most prominently increased in both chronic hypoxia and MCT models of pulmonary hypertension. α1 integrin, when dimerized to β1 integrin is a major receptor for collagen [4,28], with a preference for type IV collagen, the basement membrane collagen [29]. In addition to type IV collagen adhesion, α1β1 integrin mediates feedback regulation of type I collagen synthesis and collagen-dependent proliferation [29]. Its expression is associated with the differentiated phenotype of SMCs, where transition from a contractile to synthetic phenotype results in its downregulation at both transcript and protein levels [28,30]. Levels of the ligand, type IV collagen, are increased in PAs of animals with chronic hypoxia and MCT-induced pulmonary hypertension [3,24], along with the expression and activity of MMP-2, which degrades collagen type IV [1,6]. Loss of intact type IV collagen accompanying basement membrane degradation is associated with SMC dedifferentiation and a correlative increase in SMC migration [31]. We hypothesize that the upregulation of α1 integrin in hypertensive PAs increases the sensitivity of PASMCs to intact type IV collagen, in order to maintain SMCs in a differentiated state counteracting the dedifferentiation process involved with the progression of pulmonary hypertension.

In addition to the α1 integrin, αv and α8 integrins are upregulated in PAs of chronic hypoxia and MCT-treated rats. αv-protein dimerizes with β1, β3, β5, β6, and β8 integrins to recognize RGD-containing ligands, including vitronectin, fibronectin, fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, thrombospondin, osteopontin and collagen [8]. Its increased protein levels in PAs isolated from chronic hypoxia and MCT-treated rats is consistent with previous studies in the systemic vasculature demonstrating, for example, its upregulation in small mesenteric arteries of hypertensive rats [32,33] as well as in the neointima of various animal models of vascular injury [11,32,34]. αvβ3 integrin is furthermore involved in PASMC hyperplasia in the MCT model of pulmonary hypertension [1,12,13]. Many studies including those in the pulmonary vasculature show reduced vascular response to injury via decreased SMC proliferation and migration, MMP production and increased SMC apoptosis upon αvβ3 inhibition [34,35,36,37]. The increase in αv integrin observed in this study may contribute to PASMC proliferation and migration in pulmonary hypertension as a part of the vascular remodeling process.

α8 integrin is highly expressed in vascular smooth muscle and dimerizes with β1 integrin to bind ligands such as tenascin-C, vitronectin and fibronectin [8,38,39]. Expression of α8β1 integrin has been proposed as required for maintaining the contractile, differentiated phenotype of vascular SMCs. Indeed, α8 integrin expression is decreased during neointimal formation. α8 integrin gene silencing increases vascular SMC migration and expression of SMC de-differentiation markers. α8 integrin overexpression attenuates SMC migratory activity and restores contractile phenotypes [11,38,39]. On the other hand, integrin α5β1, the prototypical receptor for fibronectin, acts as a signal for cell proliferation [40,41]. It is involved in the polymerization of fibronectin, which promotes SMC replication, migration and survival, and the overall maintenance of a synthetic phenotype [41]. α5 integrin was decreased in both models of pulmonary hypertension. Thus, the upregulation of α8 integrin and downregulation of α5 integrin PAs obtained from both models of pulmonary hypertension may provide feedback signals to maintain the contractile phenotype of PASMCs and offset pulmonary vascular remodeling.

Compared to the large repertoire of α-subunits, the number of β integrins is limited. Only 8 β integrins are available to heterodimerize with 18 α-subunits. Of the 24 αβ heterodimers identified to date, 12 contain the β1, while the major partner for β3 integrin is αv[8]. β1 and β3 integrins were decreased in PAs of chronic hypoxia and MCT models of pulmonary hypertension, respectively. Inhibition of β1 integrin has been shown to reduce vascular SMC migration and adhesion [42,43], and knockout as well as blockade of β3 integrin decreased neointimal thickening and SMC migration in injured arteries [37,44]. Since β integrins heteromerize with various α-subtypes, the modest decrease in β1 and β3 levels may limit the availability of functionally active heterodimeric integrins, although its significance within the context of pulmonary hypertension is presently unclear.

The changes in integrin protein expression detected by immunoblot in PA of pulmonary hypertensive rat models are likely translated into alterations of integrin-dependent signaling. This is evidenced by further examining the functional consequences of differential α1 and α5 integrin expression in the chronic hypoxia model. α1 and α5 integrins were chosen due to the availability of RGD peptides and ECM proteins that target these integrins relatively specifically. The predominant α1 and α5 integrin immunoreactivity on the surface of PASMCs of chronically hypoxic rats suggest that the integrin proteins are incorporated into the sarcolemma, precluding the possibility that cytosolic accumulation of nonfunctional integrin proteins may contribute to the immunoblot data. A higher integrin-dependent activity is supported by the elevated level of FAK phosphorylation, a major downstream signaling pathway, in PASM of hypoxic rats. The enhanced phosphorylation could be related in part to the upregulated α1 integrin because it was maintained in PASMCs isolated from hypoxic rats that were cultured on the α1β1 ligand type IV collagen, but not on the α5β1 ligand fibronectin. Upregulation of α1 integrin in the chronic hypoxic PASMCs was furthermore reflected in the increased Ca2+ mobilization elicited by the α1 integrin-binding peptide, GRGDTP, in a manner similar to the collagen IV-induced Ca2+ response observed in other cell types [45,46]. Likewise, the decreased α5 integrin expression correlated with the reduced sustained Ca2+ response of chronic hypoxic PASMCs to the α5 integrin-binding hexapeptide, GRGDNP. It has to be mentioned, however, that the Ca2+ response induced by soluble RGD peptide ligands may only partially reflect the signaling induced by the immobile ligands within the native tissue.

The unique kinetic profiles of the intracellular Ca2+ transients elicited by the hexapeptides, GRGDTP and GRGDNP, suggest that integrins mobilize intracellular Ca2+ through subtype-specific pathways. Indeed, although both αvβ3 and α5β1 integrins are necessary for myogenic constriction in cremester arterioles [47], α5β1 integrin activation causes vasoconstriction through L-type Ca2+ channel potentiation, while αvβ3 ligands induce vasodilation, K+ current activation and L-type Ca2+ channel inhibition [9]. We have also shown that the common integrin ligand GRGDSP mediates Ca2+ release from ryanodine-gated Ca2+ stores and lysosome-related acidic organelles in rat PASMCs [10]. The diverse modes of Ca2+ mobilization transduced by the various integrins are likely linked to the ultimate downstream effect and function of the specific integrins. It will be important in the future to address the Ca2+ signaling pathways linked to the specific integrins that are altered in pulmonary hypertension.

In summary, we quantified the integrin levels in PAs of chronic hypoxia and MCT-induced pulmonary hypertensive rats. The similarity in the regulation of α-integrin expression in the two models suggest that they are related generally to pulmonary hypertension, and not to the direct effects of hypoxia or MCT on the pulmonary vasculature. The differential regulation of integrins in the PAs of pulmonary hypertensive animals exemplifies the complex nature of ECM/integrin-mediated signaling, and underscores the multifactorial nature of the mechanisms involved in pulmonary hypertension. Although the exact mechanisms leading to the development of pulmonary hypertension are a topic of active debate, the results of this study highlighting the involvement of a new player, namely integrins, in pulmonary hypertension along with its ECM ligands that play a major role in disease pathogenesis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Lynn Schapp (University of Washington) for generously providing the antiserum to α8 integrin, Lionel McIntosh and Holly Rohde for technical assistance, and Dr. Xiao-Ru Yang for sage advice. This work was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL-071835 and HL-075134 to J.S.K.S. and a Pulmonary Hypertension Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Award to A.U.

References

- 1.Humbert M, Morrell NW, Archer SL, Stenmark KR, MacLean MR, Lang IM, Christman BW, Weir EK, Eickelberg O, Voelkel NF, Rabinovitch M. Cellular and molecular pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:13S–24S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botney MD, Kaiser LR, Cooper JD, Mecham RP, Parghi D, Roby J, Parks WC. Extracellular matrix protein gene expression in atherosclerotic hypertensive pulmonary arteries. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:357–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crouch EC, Parks WC, Rosenbaum JL, Chang D, Whitehouse L, Wu LJ, Stenmark KR, Orton EC, Mecham RP. Regulation of collagen production by medial smooth muscle cells in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1045–1051. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durmowicz AG, Stenmark KR. Mechanisms of structural remodeling in chronic pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Rev. 1999;20:e91–e102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaidi SH, You XM, Ciura S, Husain M, Rabinovitch M. Overexpression of the serine elastase inhibitor elafin protects transgenic mice from hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2002;105:516–521. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassoun PM. Deciphering the ‘matrix’ in pulmonary vascular remodelling. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:778–779. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00027305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowan KN, Heilbut A, Humpl T, Lam C, Ito S, Rabinovitch M. Complete reversal of fatal pulmonary hypertension in rats by a serine elastase inhibitor. Nat Med. 2000;6:698–702. doi: 10.1038/76282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3901–3903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Lemus LA, Wu X, Wilson E, Hill MA, Davis GE, Davis MJ, Meininger GA. Integrins as unique receptors for vascular control. J Vasc Res. 2003;40:211–233. doi: 10.1159/000071886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umesh A, Thompson MA, Chini EN, Yip KP, Sham JS. Integrin ligands mobilize Ca2+ from ryanodine receptor-gated stores and lysosome-related acidic organelles in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34312–34323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heerkens EH, Izzard AS, Heagerty AM. Integrins, vascular remodeling, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1–4. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252753.63224.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones PL, Jones FS, Zhou B, Rabinovitch M. Induction of vascular smooth muscle cell tenascin-C gene expression by denatured type I collagen is dependent upon a beta3 integrin-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and a 122-base pair promoter element. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 4):435–445. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones PL, Crack J, Rabinovitch M. Regulation of tenascin-C, a vascular smooth muscle cell survival factor that interacts with the alpha v beta 3 integrin to promote epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation and growth. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:279–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bull TM, Coldren CD, Geraci MW, Voelkel NF. Gene expression profiling in pulmonary hypertension. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:117–120. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-128JG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimoda LA, Sham JS, Shimoda TH, Sylvester JT. L-type Ca2+ channels, resting [Ca2+]i, and ET-1-induced responses in chronically hypoxic pulmonary myocytes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L884–894. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.5.L884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones R, Jacobson M, Steudel W. alpha-smooth-muscle actin and microvascular precursor smooth-muscle cells in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:582–594. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.4.3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong H, Simons JW. Direct comparison of GAPDH, β-actin, cyclophilin, and 28S rRNA as internal standards for quantifying RNA levels under hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:523–526. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dedhar S, Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher MD. A cell surface receptor complex for collagen type I recognizes the Arg-Gly-Asp sequence. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:585–593. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierschbacher MD, Ruoslahti E. Influence of stereochemistry of the sequence Arg-Gly-Asp-Xaa on binding specificity in cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:17294–17298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poiani GJ, Tozzi CA, Yohn SE, Pierce RA, Belsky SA, Berg RA, Yu SY, Deak SB, Riley DJ. Collagen and elastin metabolism in hypertensive pulmonary arteries of rats. Circ Res. 1990;66:968–978. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.4.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estrada KD, Chesler NC. Collagen-related gene and protein expression changes in the lung in response to chronic hypoxia. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2009;8:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s10237-008-0133-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg JT, Breen EC, Fu Z, Mathieu-Costello O, West JB. Alveolar hypoxia increases gene expression of extracellular matrix proteins and platelet-derived growth factor-B in lung parenchyma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1920–1928. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9804076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vyas-Somani AC, Aziz SM, Arcot SA, Gillespie MN, Olson JW, Lipke DW. Temporal alterations in basement membrane components in the pulmonary vasculature of the chronically hypoxic rat: impact of hypoxia and recovery. Am J Med Sci. 1996;312:54–67. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipke DW, Arcot SS, Gillespie MN, Olson JW. Temporal alterations in specific basement membrane components in lungs from monocrotaline-treated rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;9:418–428. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/9.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka Y, Bernstein ML, Mecham RP, Patterson GA, Cooper JD, Botney MD. Site-specific responses to monocrotaline-induced vascular injury: evidence for two distinct mechanisms of remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:390–397. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.3.8810644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipke DL, Aziz SM, Fagerland JA, Majesky M, Arcot SS. Tenascin synthesis, deposition, and isoforms in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertensive rat lungs. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:L208–L215. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.2.L208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todorovich-Hunter L, Johnson DJ, Ranger P, Keeley FW, Rabinovitch M. Altered elastin and collagen synthesis associated with progressive pulmonary hypertension induced by monocrotaline. A biochemical and ultrastructural study. Lab Invest. 1988;58:184–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belkin VM, Belkin AM, Koteliansky VE. Human smooth muscle VLA-1 integrin: purification, substrate specificity, localization in aorta, and expression during development. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2159–2170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.5.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heino J. The collagen receptor integrins have distinct ligand recognition and signaling functions. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:319–323. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Obata H, Hayashi K, Nishida W, Momiyama T, Uchida A, Ochi T, Sobue K. Smooth muscle cell phenotype-dependent transcriptional regulation of the α1 integrin gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26643–26651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aguilera CM, George SJ, Johnson JL, Newby AC. Relationship between type IV collagen degradation, metalloproteinase activity and smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation in cultured human saphenous vein. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:679–688. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heerkens EH, Shaw L, Ryding A, Brooker G, Mullins JJ, Austin C, Ohanian V, Heagerty AM. αv integrins are necessary for eutrophic inward remodeling of small arteries in hypertension. Hypertension. 2006;47:281–287. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000198428.45132.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Intengan HD, Thibault G, Li JS, Schiffrin EL. Resistance artery mechanics, structure, and extracellular components in spontaneously hypertensive rats: effects of angiotensin receptor antagonism and converting enzyme inhibition. Circulation. 1999;100:2267–2275. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.22.2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Zee R, Murohara T, Passeri J, Kearney M, Cheresh DA, Isner JM. Reduced intimal thickening following αvβ3 blockade is associated with smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Cell Adhes Commun. 1998;6:371–379. doi: 10.3109/15419069809109146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merklinger SL, Jones PL, Martinez EC, Rabinovitch M. Epidermal growth factor receptor blockade mediates smooth muscle cell apoptosis and improves survival in rats with pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2005;112:423–431. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bendeck MP, Irvin C, Reidy M, Smith L, Mulholland D, Horton M, Giachelli CM. Smooth muscle cell matrix metalloproteinase production is stimulated via αvβ3 integrin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1467–1472. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.6.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slepian MJ, Massia SP, Dehdashti B, Fritz A, Whitesell L. β3-integrins rather than β1-integrins dominate integrin-matrix interactions involved in postinjury smooth muscle cell migration. Circulation. 1998;97:1818–1827. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zargham R, Touyz RM, Thibault G. α8 Integrin overexpression in de-differentiated vascular smooth muscle cells attenuates migratory activity and restores the characteristics of the differentiated phenotype. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zargham R, Thibault G. α8β1 Integrin expression in the rat carotid artery: involvement in smooth muscle cell migration and neointima formation. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:813–822. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davenpeck KL, Marcinkiewicz C, Wang D, Niculescu R, Shi Y, Martin JL, Zalewski A. Regional differences in integrin expression: role of α5β1 in regulating smooth muscle cell functions. Circ Res. 2001;88:352–358. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pickering JG, Chow LH, Li S, Rogers KA, Rocnik EF, Zhong R, Chan BM. α5β1 inte-grin expression and luminal edge fibronectin matrix assembly by smooth muscle cells after arterial injury. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64750-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itoh H, Nelson PR, Mureebe L, Horowitz A, Kent KC. The role of integrins in saphenous vein vascular smooth muscle cell migration. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25:1061–1069. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee RT, Berditchevski F, Cheng GC, Hemler ME. Integrin-mediated collagen matrix reorganization by cultured human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1995;76:209–214. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi ET, Khan MF, Leidenfrost JE, Collins ET, Boc KP, Villa BR, Novack DV, Parks WC, Abendschein DR. β3-integrin mediates smooth muscle cell accumulation in neointima after carotid ligation in mice. Circulation. 2004;109:1564–1569. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121733.68724.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Somogyi L, Lasic Z, Vukicevic S, Banfic H. Collagen type IV stimulates an increase in intracellular Ca2+ in pancreatic acinar cells via activation of phospholipase C. Biochem J. 1994;299:603–611. doi: 10.1042/bj2990603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savarese DM, Russell JT, Fatatis A, Liotta LA. Type IV collagen stimulates an increase in intracellular calcium. Potential role in tumor cell motility. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21928–21935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinez-Lemus LA, Crow T, Davis MJ, Meininger GA. αvβ3- and α5β1-integrin blockade inhibits myogenic constriction of skeletal muscle resistance arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H322–H329. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00923.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]