Abstract

B cell development is exquisitely sensitive to location within specialized niches in the bone marrow and spleen. Location within these niches is carefully orchestrated through chemotactic and adhesive cues. Here we demonstrate the requirement for the actin-bundling protein L-plastin (LPL) in B cell motility towards the chemokines CXCL12 and CXCL13 and the lipid chemoattractant sphingosine-1-phosphate, which guide normal B cell development. Impaired motility of B cells in LPL−/− mice correlated with diminished splenic maturation of B cells, with a moderate (40%) loss of follicular B cells and a profound (>80%) loss of marginal zone B cells. Entry of LPL−/− B cells into the lymph nodes and bone marrow of mice was also impaired. Furthermore, LPL was required for the integrin-mediated enhancement of transwell migration but was dispensable for integrin-mediated lymphocyte adhesion. These results suggest that LPL may participate in signaling that enables lymphocyte transmigration. In support of this hypothesis, the phosphorylation of Pyk-2, a tyrosine kinase that integrates chemotactic and adhesive cues, is diminshed in LPL−/− B cells stimulated with chemokine. Finally, a well-characterized role of marginal zone B cells is the generation of a rapid humoral response to polysaccharide antigens. LPL−/− mice exhibited a defective antibody response to Streptococcus pneumoniae, indicating a functional consequence of defective MZ B cell development in LPL−/− mice.

Keywords: B cells, chemokines, actin-binding proteins

Introduction

Lymphocyte motility depends upon tightly regulated rearrangements in the actin cytoskeleton (1, 2). Actin-binding proteins coordinate the rapid cytoskeletal changes required for motility, including the polymerization of actin, the generation of actin-based structures such as lamellipodia, and the polarization of lymphocytes (3). L-plastin (LPL), an actin-bundling protein uniquely expressed in hematopoietic cells, is required for normal motility of T lymphocytes and for full T cell activation (4, 5). LPL binds two F-actin helices to create tightly cross-linked bundles of parallel actin filaments, and thus stabilizes larger-order actin structures (6). LPL is the only member of the plastin subclass of actin-bundling proteins expressed in hematopoietic cells. LPL has no defined function in signal transduction beyond its capacity to bundle actin filaments, and the mechanism by which LPL functions in lymphocyte motility remains unclear. Furthermore, while LPL is required for the adhesion-dependent respiratory burst in neutrophils, LPL is dispensable for neutrophil motility (7). The requirement for LPL in motility of hematopoietically-derived cells is therefore cell-specific. To determine if LPL is required for motility of B lymphocytes, and to further elucidate the mechanism by which LPL functions in lymphocyte motility, we investigated the dependence of B cell motility and B cell development on LPL.

B cell motility during B cell maturation is guided by chemokines and the lipid chemoattractant, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P). Chemokines, small protein chemoattractants, decorate the stromal network of fibroblasts and epithelial cells that create the cellular framework of secondary lymphoid organs through which lymphocytes continually recirculate (8). Chemokine receptors are seven-transmembrane G-protein-coupled proteins that enable the lymphocytes on which they are expressed to navigate lymphoid compartments. Chemokines and their receptors thus determine both underlying lymphoid architecture and lymphocyte movement through and localization within this architecture. CXCR4, the chemokine receptor for CXCL12, and CXCR5, the receptor for CXCL13, are critical for B cell development (9, 10).

B cell development begins in the bone marrow and is completed in the spleen (reviewed in (11)). In the bone marrow, CXCL12 and CXCR4 retain the earliest B cell precursors within the appropriate bone marrow niches required for B cell maturation (12). Following successful rearrangement of the immunoglobulin locus to generate and express IgM, immature B cells emigrate from the bone marrow, guided by receptors for S1P (13–15). Entering the spleen through the bloodstream, these immature B cells form the population of transitional B cells. CXCL13 and CXCR5 guide B cells to the B cell compartment within splenic and lymph node tissue. In the absence of CXCR5 or CXCL13, lymphoid architecture is disturbed, devoid of clearly defined B and T cell zones or B cell follicles (9, 16). Transitional B cells move through the red pulp, cross the barrier of cells lining the marginal sinus of the spleen, and enter the white pulp. In the white pulp transitional B cells generate IgD and develop into either follicular or marginal zone (MZ) B cells.

Chemotactic cues guide the development of MZ B cells, as MZ B cell development requires the appropriate localization of maturing B cells at the border of the follicle and the red pulp (11). MZ B cells are among the first immune cells to capture bloodborne antigens and can generate rapid humoral responses to T-independent antigens. Absence of MZ B cells reduces the humoral reponse mounted to polysaccharide antigens (17). MZ B cells also traffic into the follicle to stimulate an adaptive response (18). Development of splenic MZ B cells is especially sensitive to location within the appopriate lymphoid architecture (19, 20). Deficienices of proteins such as Dock2, Dock8, Rap1B, and Pyk-2, required for chemotaxis and adhesion, can disrupt the localization and maturation of MZ B cells (17, 21–24).

Here we present the requirement for LPL in B cell motility and MZ B cell development. Developing B cells isolated from the bone marrow of LPL−/− mice demonstrated diminished motility towards CXCL12 and S1P. In spite of reduced movement towards CXCL12, bone marrow development of early B cell precursors was not impacted in LPL−/− mice. However, there was a 40% decrease in the number of mature B cells isolated from the spleens of LPL−/− mice, and MZ B cells were nearly absent. Splenic architecture was not disrupted in LPL−/− mice, and defective MZ B cell maturation was intrinsic to LPL−/− B cells, suggesting that LPL−/− B cells could not migrate to the correct splenic niches to complete MZ B cell maturation. Functionally, LPL−/− mice demonstrated a reduced humoral response to intravenous challenge with the polysaccahride antigen heat-killed Streptococcus pneumoniae, as would be predicted from a deficit of MZ B cells. MZ B cell development thus requires LPL.

Materials and Methods

Mice

LPL−/− mice were used between the ages of 5 and 14 weeks (7). Age- and gender-matched wild-type (WT) mice were bred and maintained in the same specific pathogen-free housing as LPL−/− mice at Washington University School of Medicine. All experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

Cell isolation

For determination of cell counts, two axillary and two inguinal lymph nodes were isolated from each mouse. Single cell suspensions were generated from lymph nodes and spleen by gentle disruption of the tissue with a 3 ml syringe in a small culture dish to release the lymphocytes. Peritoneal cells were harvested by washing the peritoneal cavity with 8–10 ml of sterile PBS. Bone marrow cells were isolated from both femurs and tibias of each mouse unless otherwise noted.

Flow cytometry

Directly conjugated antibodies were commercially available: anti-IgM-FITC (clone II/41), anti-B220-PerCPCy5.5 (clone RA3), anti-IgD-PE (clone 11–26), anti-CD23-PE (clone B3B4), anti-CD1d-biotin (clone 1B1), streptavidin-allophycocyanin (APC), AA4.1-APC (clone AA4.1), anti-CD11b-FITC (clone M1/70), anti-CD5-biotin (clone 53-7.3), anti-CD69-FITC (clone H1.2F3), anti-CD86-PE (clone GL1) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA); anti-CD43-PE (clone 1B11), anti-CD21/35-FITC (clone 7E9), anti-IgM-biotin (clone RMM-1), anti-CD45.1-APC/Cy7 (clone A20), anti-CD45.2-PE/Cy7 (clone 104), anti-CD24-PE/Cy7 (clone M1/69), anti-IgD-Pacific Blue (clone 11–26c.2a), anti-Ly51-biotin (clone 6C3) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). All samples were blocked with 1 μg Fc-block (anti-CD16/32, clone 93, eBioscience). Cells were acquired either with a FACSCalibur, a modified FACScan, or LSR (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc., Ashland, OR).

BrdU incorporation

Assessment of cell turnover was determined using BrdU incorporation (25, 26). BrdU incorporation into bone marrow and splenic B cell subsets was assessed using the BD Biosciences BrdU-APC kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions, 48 h after mice were injected i.p. with 2 mg BrdU in PBS (10 mg/ml; BD Biosciences and Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Transwell assays

Transwell inserts (5 μM; Corning Costar, Lowell, MA) were incubated overnight at 4°C with recombinant murine VCAM-1-Fc chimera (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or with an equivalent concentration of the control protein BSA, and washed with sterile PBS. Transmigration assays were performed as described (4) with CXCL12, CXCL13 (R&D Systems) or sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P; Sigma) at the indicated concentrations. After incubation for 3–4 h at 37°C, cells were recovered from the lower chamber and counted using a hemocytometer with subpopulations determined by flow cytometry. Percentage of migrated cells was determined by dividing the number of migrated cells, gated as indicated, by the total number of equivalently gated input cells.

Generation of bone marrow chimeras

Bone marrow was harvested from WT (CD45.1) and LPL−/− (CD45.2) mice, mixed and injected either retro-orbitally or i.v. via tail vein injection into irradiated (900–1000 rads) WT (CD45.1) mice. After 6 wks, mice were sacrificed and bone marrow, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, lymph node cells and splenocytes were assessed for expression of IgD, IgM, B220, CD43, AA4.1, CD21/35, CD23, CD1d, CD45.1, and CD45.2 by flow cytometry.

Lymphoid organ entry

B cells were isolated from WT or LPL−/− splenocytes using B cell negative isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA). Purity of isolated cells was >98% B220+ as determined by flow cytometry. B cells from WT mice were labeled with CFSE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and B cells from LPL−/− mice were labeled with Cell Trace Far Red DDAO (Invitrogen). Labeled cells were mixed and injected i.v. via tail vein injection into WT recipient mice. After 3 h, peripheral blood monocytes, lymph nodes, spleens and bone marrow were obtained from recipient mice and proportions of B220+ transferred cells were determined by flow cytometry. The ratio of LPL−/−:WT derived cells from each organ was divided by the ratio of LPL−/−:WT cells in the mix injected into each mouse, to normalize ratios across multiple experiments.

Adhesion assays

Adhesion assays were performed as described previously, with minor modifications (22, 27–29). Flat-bottomed 96-well Immulon plates were coated overnight with Fc-VCAM-1 (1 or 3 μg/ml) with BSA or with CXCL12 (500 ng/ml) in PBS at 4°C. Plates were washed with PBS, then blocked with 1% BSA in PBS at 37°C for 1 h. Splenocytes from WT or LPL−/− mice were incubated in complete I10 media (IMDM plus 10% FBS, 10 mM Hepes) in a cell culture flask for 30 min at 37°C to remove adherent cells. Non-adherent splenocytes were removed from the flasks, subjected to RBC lysis, washed, and resuspended in warmed serum-free media (RPMI with 10 mM Hepes and 0.5% BSA) and rested for at least 1 h at 37°C. Cells (5 × 104/well) were plated onto the blocked plate, briefly centrifuged to settle cells (30 – 50 g × 20 s) and incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Experimental wells were washed with warm serum-free media eight times. Adherent cells were then detached by incubation for 20 m on ice with cold RPMI with 10 mM EDTA. The number of “input” cells was determined from control wells coated with BSA in which cells were plated but not subjected to washing and detachment. Cells recovered from each well were counted and analyzed for expression of B220, CD23, and CD21/35 by flow cytometry. Percentage of adherent cells was determined by dividing the number of cells, gated as indicated, by the total number of equivalently gated input cells.

Upregulation of activation markers and proliferation

B220+ cells isolated from WT or LPL−/− splenocytes were incubated overnight with plate-bound anti-IgM. Upregulation of CD69 and CD86 on B cells was assessed by flow cytometry.

For proliferation assays, B220+ cells isolated from WT or LPL−/− splenocytes using negative selection (Miltenyi Biotec Inc.) and were labeled with CFSE (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated for 72 h in the absence or presence of soluble anti-IgM stimulation (10 μg/ml; F(ab')2 fragment of goat anti-mouse IgM, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), and rIL-4 (10 ng/ml, R&D Systems). Cells were analyzed for CFSE dilution by flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemistry

Spleens from naïve WT and LPL−/− mice were embedded in OCT (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), frozen with 2-methylbutane cooled in liquid nitrogen, sectioned, fixed with acetone, and stored at −20 °C before staining. For staining, the 8 μm sections were rehydrated with PBS, blocked with 5% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in 0.1% Tween-20, and stained with anti-MOMA-FITC (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC), anti-B220-PE, anti-IgD, anti-IgM (eBioscience), anti-IgM-Biotin, or anti-Thy1.2-AF488 (BioLegend). Secondaries used were Streptavidin-Dylight 594, Streptavidin-Dylight 488 (BioLegend), or Alexa Fluor 594 anti-rat IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen). Sections were mounted and visualized on a Zeiss Axioskop using a Zeiss Plan-Neufluar 10× or 20× objective or an Olympus BX60 using an Olympus U Plan Fl 20× objective. Images were acquired using a Zeiss AxioCam with AxioVision software. Color levels (brightness and contrast) were adjusted in Adobe PhotoShop.

Immunoblots

Purified B220+ cells (Miltenyi Biotec) from WT or LPL−/− spleens were stimulated with CXCL12 (100 ng/ml) or the F(ab')2 fragment of goat anti-mouse IgM (10 μg/ml; Jackson ImmunoResearch) for the indicated time. Cells were lysed in TNE buffer with protease inhbitors added. Post-nuclear lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were probed with the indicated primary antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Goat anti-rabbit-AlexaFluor680 (Invitrogen) and goat anti-mouse-IRDye800 (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) antibodies were used to detect membrane bound antibodies. Signal was visualized and quantified using LiCOR Odyssey imager and software (LiCor, Lincoln, NE). To compare the degree to which phosphorylation of each protein was stimulated in WT and LPL−/− B cells, the ratio of each phospho-specific protein to the total protein level in stimulated cells was determined, and then normalized to the ratio of the phospho-specific protein to the total level of protein in unstimulated cells.

Determination of IgM response to i.v. Streptococcus pneumoniae

Mice were injected intra-venously with 1×107 cfu heat-killed Streptococcus pneumoniae (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) in 100 μl HBSS. Mice were bled at the indicated time-points following immunization. Sera were plated at an initial dilution of 1:30 and diluted serially 1:3 in Immulon II plates (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) coated with 5 μg/ml phosphorylcholine-BSA (Biosearch Technologies, Inc., Novato, CA) and blocked with PBS/0.1%Tween/1%BSA. Bound serum antibody was detected by anti-mouse IgM-HRP (1:2500) (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) and developed for at least 15 min using ABTS substrate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Absorbance was measured at 410 nm on a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Statistics

The Mann-Whitney test was used to determine statistical significance, with p < 0.05 considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

LPL required for motility, but not development, of B cells in the bone marrow

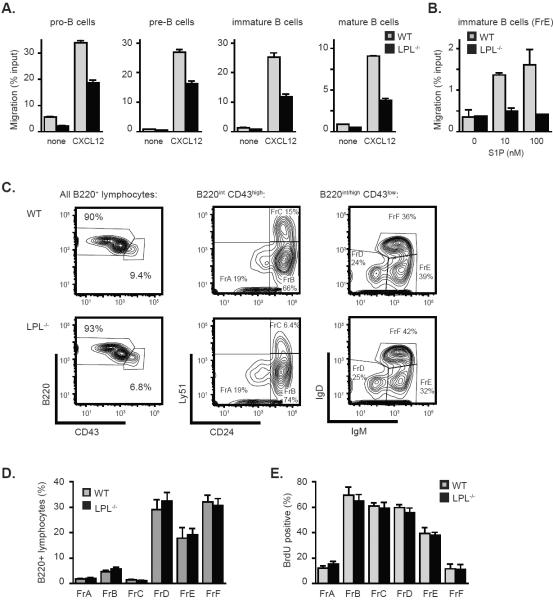

Chemokine-induced motility of thymocytes and T cells depends upon the actin-binding protein LPL (4). We hypothesized that B cell motility would also require LPL. B220+ cells were isolated from the bone marrow of WT and LPL−/− mice and defined as pro-B, pre-B, immature and mature B cells based upon expression of B220, IgM, and CD43 (Fig. S1A). Pro-B, pre-B, immature B, and mature B cells isolated from LPL−/− mice all demonstrated reduced motility towards CXCL12, despite normal expression of CXCR4 (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1B). Increasing the concentration of CXCL12 was insufficient to overcome the diminished motility of LPL−/− B cells (Fig. S1C). Immature LPL−/− B cells (defined as Hardy Fraction E, see below) also demonstrated reduced motility to the lipid chemoattractant (S1P), indicating that motility induced by multiple chemoattractant receptors requires LPL (Fig. 1B). Interactions between CXCL12 and CXCR4 are essential for B cell production in the bone marrow (10), and interactions between S1P and at least two receptors, S1P1 and S1P3, regulate bone marrow egress of immature B cells (13–15). To determine whether diminished motility towards CXCL12 or S1P would impact bone marrow development of B cells in LPL−/− mice, we employed the Hardy method to delineate subsets of developing B cells using the markers B220, CD43, Ly51, CD24, IgM and IgD to determine fractions A-F (FrA – FrF) (Fig. 1C) (30). Despite the requirement for LPL in CXCL12- and S1P-stimulated motility, bone marrow development of B cells proceeded normally in LPL−/− mice (Fig. 1C, 1D). Additionally, turnover of bone marrow subsets in LPL−/− mice, assessed using BrdU incorporation, appeared normal (Fig. 1E), in contrast to the reduced turnover of immature B cells observed in mice deficient for S1P1 (15). Thus, chemoattractant-induced motility appeared to be dispensable for B cell development, indicating that other functions of CXCR4 and receptors for S1P must be required for B cell maturation in the bone marrow.

Figure 1.

Normal bone marrow development of B cells in LPL−/− mice despite dependence of chemoattractant-induced motility upon LPL. (A) CXCL12 (100 ng/ml)-stimulated transwell migration of bone marrow cells isolated from WT (grey bars) or LPL−/− (filled bars) mice. Data presented as mean ± SEM of triplicate samples from two independent experiments. (B) S1P-stimulated transwell migration of immature B220+CD43lowIgM+IgDlow (FrE) bone marrow cells from WT (grey bars) or LPL−/− (filled bars) mice. Data presented as mean ± SEM of duplicate samples from one of two independent experiments. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of of B220, CD43, CD24, Ly51, IgM and IgD expression on gated lymphocytes from bone marrow of WT or LPL−/− mice. Representative of 7 pairs of mice (age-matched between 8 and 12 weeks). (D) Subset delineation from the bone marrow of WT (grey bars; n=7) and LPL−/− (filled bars; n=7) mice using Hardy fractions, as determined using the gating strategy depicted in (C). Data presented as mean ± SEM. (E) BrdU incorporation into bone marrow B220+ cell subsets isolated from WT (grey bars) or LPL−/− (filled bars) mice. Data shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6 WT and LPL−/− mice, from three independent experiments).

Defective maturation of MZ B cells in LPL−/− mice

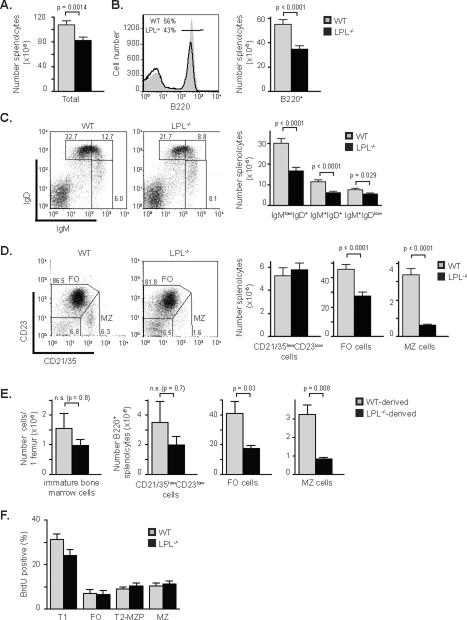

Following egress from the bone marrow, immature B cells traffic to the spleen, forming the subset of T1 splenic B cells that then undergo further maturation (22). Spleens from LPL−/−mice contained fewer lymphocytes overall (Fig. 2A), and fewer B220+ cells (Fig. 2B). The percentage of IgMhighIgDlow B cells was maintained in LPL−/− mice while the percentages of IgMhighIgDhigh and IgMlowIgDhigh populations were diminished (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2A). Numerically, there was a loss of the more mature IgMhighIgDhigh and IgMlowIgDhigh populations, relative to the slight reduction in the number of IgMhighIgDlow B cells (Fig. 2C). The IgMhighIgDlow population of B220+ cells contains both immature transitional B cells and MZ B cells. To better define the subsets of splenic B220+ cells, we analyzed the expression of the surface markers CD21/35 and CD23. Follicular (FO) B cells have been defined as CD23highCD21/35int, MZ B cells as CD23lowCD21/35high, and “newly-forming” cells as CD23lowCD21/35low (23). Numbers of FO cells were reduced by approximately 40% and numbers of MZ B cells were reduced by 80% in the spleens of LPL−/− mice (Fig. 2D). The numbers of newly-forming B cells were equivalent in the spleens of WT and LPL−/− mice. Four color analysis of the expression of IgM, CD21/35, CD23 and B220, performed on a sample subset, confirmed that the number of early T1 splenic B cells, defined as B220+CD23negIgMhighCD21/35neg, was maintained in the spleens of LPL−/− mice, while more mature populations of FO, T2 and marginal zone precursor (T2-MZP), and MZ B cells were lost (Fig. S2B, S2C). The maintenance of T1 B cells was confirmed by AA4.1 expression (Fig. S2D), and loss of MZ B cells was confirmed by CD1d expression (Fig. S2E). Maintenance of the immature B220+ splenocyte population is consistent with the observation that bone marrow development is normal in LPL−/− mice, and suggests little defect in trafficking of immature B cells into the spleen. Defective B cell maturation in LPL−/− mice is therefore specific to the splenic compartment.

Figure 2.

Reduced splenic maturation of B cells in LPL−/− mice, with profound loss of MZ B cells. (A) Total numbers of splenocytes isolated from WT or LPL−/− mice. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of B220 expression on splenocytes isolated from WT (filled grey histogram) or LPL−/− (solid line) mice. Bar graph depicts number of B220+ splenocytes isolated from WT or LPL−/− mice. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of IgM and IgD expression on all splenocytes isolated from WT or LPL−/− mice. Bar graph depicts number of IgMlowIgD+, IgM+IgD+, and IgM+IgDlow cells isolated from WT or LPL−/− mice. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of CD21/35 and CD23 expression on B220+ splenocytes from WT or LPL−/− mice. FO cells identified as CD21/35intCD23high and MZ cells identified as CD21/35highCD23low. Bar graphs depict number of CD21/35lowCD23low, FO, and MZ splenocytes from WT or LPL−/− mice. (A, B, C, D) All quantitative data, WT (grey bars; n = 21) and LPL−/− (filled bars; n = 25) data shown as mean ± SEM, p-value determined by Mann-Whitney test. Mice were age-matched and between 5 and 12 weeks of age, average age WT (8.2 ± 0.3 wk) and LPL−/− (8.1 ± 0.4 wk) , ages listed as mean ± SEM. (E) Numbers of cells derived from WT (grey bars) or LPL−/− (filled bars) bone marrow in competitive bone marrow chimeric mice that were either immature bone marrow B cells (B220intIgM+, as in Sup Fig 1A), or B220+ splenocyte subsets, the “newly-forming” CD21/35lowCD23low B cells, FO B cells, or MZ B cells (n = 5 chimeric mice from 3 independent experiments; data shown as mean ± SEM, p-value determined by Mann-Whitney test). (F) BrdU incorporation into splenic B220+ cell subsets isolated from WT (grey bars) or LPL−/− (filled bars) mice. Data shown as mean ± SEM (n=9 WT and 10 LPL−/− mice, from five independent experiments).

To determine if the defective MZ B cell development in LPL−/− mice was cell-intrinsic or extrinsic, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras (Fig. 2E). Analysis of bone marrow subsets in chimeric mice revealed no significant block in bone marrow maturation of B cells derived from LPL−/− bone marrow (data not shown), although some variability in engraftment into the WT recipients resulted in a statistically insignificant reduction of immature B cells derived from LPL−/− bone marrow (Fig. 2E). Analysis of splenic B220+ cells from the competitive, mixed bone marrow chimeras revealed no significant differences in the number or percentage of immature, CD21/35lowCD23low cells derived from WT or LPL−/− bone marrow (Fig. 2E, Fig. S2F), and the statistically insignificant decrease seen is likely due to the variable engraftment also observed in the bone marrow subset. However, there was a pronounced and significant reduction in the number and percentage of MZ B cells derived from LPL−/− bone marrow, demonstrating a cell-intrinsic defect in LPL−/− MZ B cell development (Fig. 2E, Fig. S2F). Additionally, there was a significant, though moderate, reduction in the number of FO B cells derived from the LPL−/− marrow, though the percentages were not significantly reduced (Fig 2E and data not shown).

Interestingly, the loss of FO and MZ B cells from LPL−/−-derived marrow in the mixed bone marrow chimeras does not appear to be as profound as the losses observed in the LPL−/−mice. For instance, the percentage of MZ B cells derived from LPL−/− bone marrow, compared to the percentage of MZ B cells derived from WT bone marrow, was reduced by about 50% (Fig. S2F), which was not as great as the 80% reduction in MZ B cells seen when comparing WT and LPL−/− mice (Fig. 2D). The partial correction of FO and MZ B cell development observed in the competitive chimeras may indicate that the splenic B cell maturation defect is partially cell-extrinsic in the LPL−/− mouse. However, the significant reduction of MZ B cells derived from LPL−/− bone marrow in a competitive chimeric assay indicated that the major requirement for LPL in MZ B cell maturation is cell-intrinsic.

A loss of both FO and MZ B cells in the competitive bone marrow chimeric mice suggested a block in early splenic maturation. Consistent with this suggestion, turnover of splenic B cell subsets in LPL−/− mice, assessed using BrdU incorporation, revealed a mild, though not statistically significant, reduction in the turnover of T1 cells in LPL−/− mice (Fig. 2F). Turnover of other splenic subsets appeared unaffected (Fig. 2F). Reduced turnover of T1 B cells in LPL−/− mice would explain the reduction in numbers of both FO and MZ B cells.

Disrupted splenic B cell maturation was not due to obviously disrupted splenic architecture. Normal separation of T and B cell regions in the spleen were maintained in LPL−/−mice (Fig. 3A), in contrast to mice deficient for the chemokine receptor CCR7 or CXCR5 (16, 31). Furthermore, reductions in the MZ B cell population in spleens from LPL−/− mice were confirmed by histology, by visualizing MOMA-1 and IgM expression or by visualizing IgM and IgD expression in the follicles (Fig. 3B and 3C). Diminished splenic B cell development in LPL−/− mice did not result in, or result from, disturbed splenic architecture

Figure 3.

Normal separation of T and B cell zones but absence of B cells in the marginal zone in spleens from LPL−/− mice. (A) T and B cell zones visualized by staining fixed, frozen sections of spleens from WT and LPL−/− mice for Thy1.1 (FITC) and B220 (PE). Images representative of 3 independent experiments from 3 pairs of mice. (B) MZ B cells visualized by staining fixed, frozen sections of spleen from WT and LPL−/− mice for IgM (AlexaFluor594) and MOMA-1-FITC. (C) MZ B cells visualized by staining fixed, frozen sections of spleen from WT and LPL−/− mice for IgM (DyLight488) and IgD (AlexaFluor594). (B, C) Arrows indicate the marginal zone. Images representative of 2 independent experiments from 2 pairs of mice. (A, B, C) Scale bar equivalent to 100 μm.

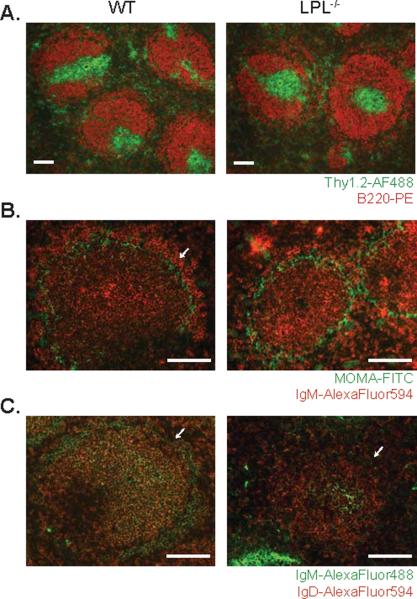

Increased numbers of B cells in the blood of LPL−/− mice

To determine if the loss of mature B cells from the spleen affected the number of peripheral B cells in other sites, the total numbers of B cells from blood and peripheral lymph nodes in LPL−/− mice were assessed. Total and B220+ lymphocytes from the blood of LPL−/− mice were greater than those of WT mice (Fig. 4A). The percentages of IgMlowIgDhigh, IgMhighIgDhigh, and IgMhighIgDlow cells were similar between WT and LPL−/− mice (Fig. 4B), while the total number of mature and immature subsets of B cells were increased in the blood of LPL−/− mice (Fig. 4C). Thus, while more B cells circulate in the bloodstream of LPL−/− mice, there was no shift towards a more immature population in the blood. There was no statistically significant difference in the numbers or percentages of total and B220+ lymphocytes isolated from the peripheral lymph nodes of WT and LPL−/− mice (Fig. 4D), and also no significant shift towards a more immature population of B cells in the lymph nodes of LPL−/− mice (Fig. 4E, 4F). These data indicate that after maturation, B cells can exit the spleen and populate the peripheral lymph nodes in LPL−/− mice.

Figure 4.

Increased numbers of lymphocytes in the blood of LPL−/− mice. (A) Total cell number and number of B220+ cells isolated from blood of WT and LPL−/− mice. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of IgM and IgD expression on peripheral blood mononuclear cells of WT and LPL−/−mice. (C) Number of IgMlowIgD+, IgM+IgD+, and IgM+IgDlow cells isolated from PBMCs of WT or LPL−/− mice. (A, C) Quantitative data from WT (grey bars; n = 16) and LPL−/− (filled bars; n = 18) mice depicted as mean ± SEM with p-value determined by Mann-Whitney test. (D) Total cell number and number of B220+ cells isolated from four peripheral lymph nodes (axillary and inguinal) of WT or LPL−/− mice. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of IgM and IgD expression on lymphoyctes isolated from lymph nodes of WT and LPL−/− mice. (F) Number of IgMlowIgD+, IgM+IgD+, and IgM+IgDlow cells isolated from lymph nodes of WT or LPL−/− mice. (D, F) Quantitative data from WT (grey bars; n = 14) and LPL−/− (filled bars; n = 16) mice depicted as mean ± SEM. (G) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of B220, CD23, CD11b and CD5 on peritoneal lymphocytes isolated from WT or LPL−/− mice. Bar graph depicts percentages of B1a, B1b, and B2 cells, determined by the gating strategy indicated, isolated from the peritoneal cavities of WT (grey bars; n = 6) or LPL−/− (filled bars; n = 6) mice (data shown as mean ± SEM).

Peritoneal B cells can be divided into subsets based on the expression of B220, CD23, CD11b and CD5 (32). The percentages of B1a (B220+CD23−CD11b+CD5+), B1b (B220+CD23-CD11b+CD5−) and B2 (B220+CD23+) cells were not diminished in LPL−/− mice (Fig. 4G), indicating that the defect in B cell development in LPL−/− mice was limited to the splenic compartment.

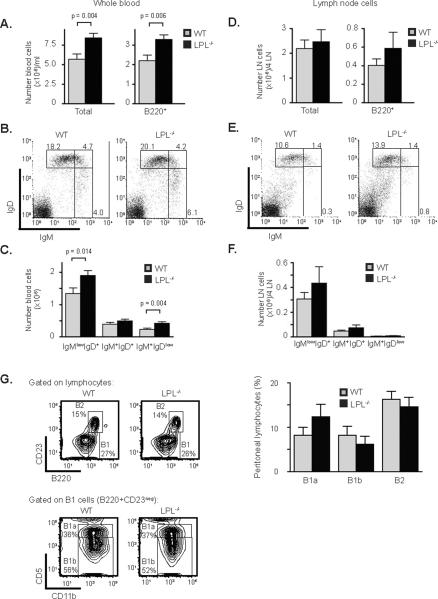

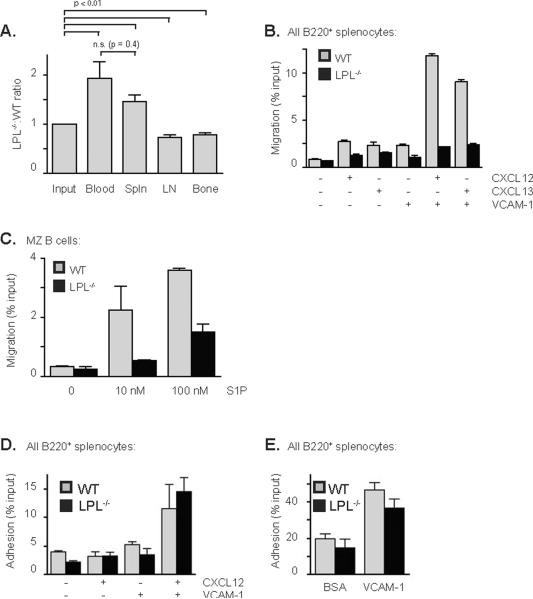

LPL−/− B cells are defective in entry into lymph nodes and bone marrow

The increased number of B220+ cells in the blood of LPL−/− mice suggested that LPL−/− B cells may be deficient in the ability to exit the blood and enter peripheral sites. We tested for deficient lymphoid organ entry by co-transferring CFSE-labeled WT and DDAO-labeled LPL−/−B220+ cells into WT mice and enumerating transferred cells in the blood, spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow of recipient mice (Fig. 5A). An increased ratio of transferred LPL−/− to WT cells in the blood and a reduced ratio of LPL−/− to WT cells in the lymph nodes and bone marrow of recipient mice indicated that LPL−/− B cells are relatively, though not absolutely, defective in the ability to enter lymphoid organs (Fig. 5A). LPL−/− B cells were able to enter the spleen normally, consistent with findings that there are normal numbers of immature B cells in the spleens of LPL−/− mice (Fig. 2C, 2D). LPL is thus required for normal B lymphocyte entry into lymph nodes and bone marrow, but not for entry into the spleen.

Figure 5.

Defective lymphoid organ entry and motility of LPL−/− B cells. (A) Ratio of LPL−/−:WT B cells isolated from each organ, with ratios normalized to that of the mix of WT and LPL−/− cells injected into each mouse (“input”). Data shown as mean ± SEM (n = 5 recipient mice in 3 independent experiments), p-value determined with Mann-Whitney test, comparing groups as shown. (B) Transwell migration of splenocytes isolated from WT (grey bars) or LPL−/− (filled bars) mice to either CXCL12 (100 ng/ml) or CXCL13 (1 μg/ml). Transwell inserts were coated with either Fc-VCAM-1 (1 μg/ml) or control protein BSA (1 μg/ml) prior to the assay. Data shown as mean ± SEM of duplicate samples from two independent experiments. (C) Transwell migration of MZ B cells from WT (grey bars) or LPL−/− (filled bars) mice towards S1P. Data shown as mean ± SEM of duplicate samples from two independent experiments. (D) Adhesion of WT (grey bars) and LPL−/− (filled bars) B cells to VCAM-1 (1 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of plate-bound CXCL12 (500 ng/ml). Data shown as mean ± SEM of triplicate samples from one of two independent experiments. (E) Adhesion of WT (grey bars) and LPL−/− (filled bars) B cells to VCAM-1 (3 μg/ml). Data shown as mean ± SEM of triplicate samples from four independent experiments.

Integrin binding did not enhance the transwell migration of LPL−/− B cells

Trafficking of B cells is regulated in part by the chemokine receptors CXCR4, CXCR5 and S1P1, and by the integrin VLA-4 (9, 16, 19, 33). We assessed the CXCL12- and CXCL13-directed motility of splenic B cells from LPL−/− mice in the presence or absence of VCAM-1, which is the ligand for VLA-4 (Fig. 5B). Integrin binding augments the ability of cells to migrate across a barrier (25), and coating the upper surface of transwell inserts with VCAM-1 dramatically increased the percentage of WT cells that crossed the insert (Fig. 5B). When analyzing the migration of all B220+ cells, we found a 50% decrease in the percentage of LPL−/−B cells that migrated to the chemokines CXCL12 and CXCL13 in the absence of integrin ligation, despite normal expression of CXCR5 and CXCR4 (Fig. S3A, S3B). Integrin binding had a negligible effect on the transmigration of LPL−/− B220+ cells (Fig. 5B). Separating the migrating cells into populations of newly-forming CD21/35negCD23neg, FO and MZ B cells revealed that both newly-forming and FO B cells from LPL−/− mice demonstrated significant defects in motility in the presence or absence of integrin ligand, while MZ B cells appeared less deficient in the absence of integrin ligation (Fig S3C). However, MZ B cells still demonstrated a requirement for LPL in chemokine-mediated motility in the presence of integrin ligand (Fig S3C). Thus, LPL is required for the integrin-induced increase in chemokine-mediated transmigration.

MZ B cells are dependent upon S1P for localization within the marginal zone (19). We therefore tested whether MZ B cell migration to S1P would require LPL. LPL−/− MZ B cells demonstrated a diminished chemotactic response to S1P (Fig 5C), indicating that LPL is required for normal motility towards S1P in mature as well as immature B cells.

Intriguingly, LPL was not required for the chemokine-enhanced adhesion to integrins. Chemokine stimulation can activate integrin-mediated adhesion in the presence of shear forces (34, 35). We tested the dependence of chemokine-activation of integrins upon LPL by using a static plate-bound adhesion assay (Fig. 5D). It is thought that the extensive washing in this assay provides the shear forces necessary to generate chemokine-mediated integrin activation (36). LPL−/− B cells adhered to plates coated with VCAM-1 and CXCL12 similarly to WT B cells (Fig. 5D, Fig. 5E). Analysis of the results presented in Fig. 5D and Fig. 5E using the additional markers CD21/35 and CD23 revealed no difference in the adhesion of WT and LPL−/− splenic B cell subsets (Fig. S3D and Fig. S3E), indicating that LPL was not required for adhesion in any splenic subset. LPL is thus dispensable for integrin-mediated adhesion, but is required for the integrin-mediated enhancement of transwell migration in response to chemokine stimulation.

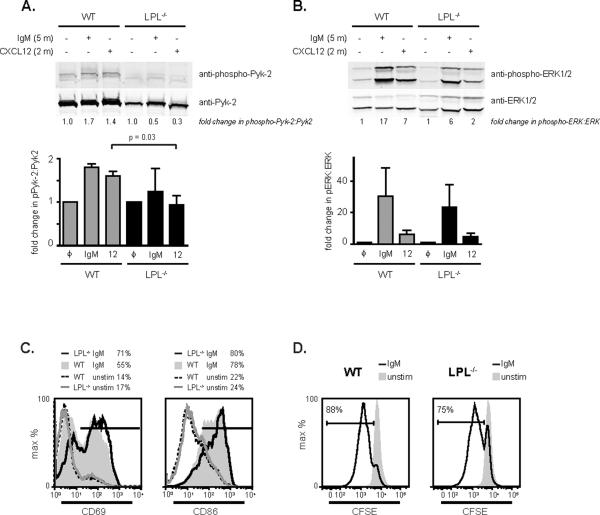

Diminished Pyk-2 phosphorylation in LPL−/− B cells following chemokine stimulation

Many downstream signaling effectors are required for chemokine-mediated motility, including the small GTPase Rac, and the kinases ERK, Akt, and Pyk-2 (reviewed in (37)). To determine if the activation of signaling molecules depended on LPL, we used phospho-specific antibodies in immunoblot assays of cell lysates from WT and LPL−/− B cells stimulated with either anti-IgM or with CXCL12 (Fig. 6A, Fig. 6B). The total cellular concentration of Pyk-2 was decreased in comparison to the levels of the kinase ERK (Fig. 6A, Fig. 6B; immunoblots of the same membrane are shown in Fig. 6A and 6B). Generation of post-nuclear lysates separates a detergent-insoluble fraction which can contain cytoskeletal elements. Immunoblot did not reveal increased partitioning of Pyk-2 into the detergent-insoluble fraction in LPL−/− B cells (data not shown), indicating that total protein expression of Pyk-2 is diminished in the absence of LPL. Furthermore, stimulation of LPL−/− B cells with CXCL12 did not result in the modest but consistent 1.5-fold increase in phosphorylation of Pyk-2 observed in CXCL12-stimulated WT B cells (Fig. 6A). Thus, both the total level and chemokine-induced phosphorylation of Pyk-2 were diminished in LPL−/− B cells. Although phosphorylation of the mediator ERK at times appeared to be slightly diminished in stimulated LPL−/− B cells, no significant reduction of ERK activation was observed in replicate experiments (Fig. 6B). Similarly, stimulation of phosphorylation of p38 was not significantly diminished in LPL−/− B cells (data not shown). Thus, the requirement of LPL for maintenance of Pyk-2 protein levels and activation-dependent phosphorylation appeared to be specific for Pyk-2.

Figure 6.

Diminished levels and phosphorylation of Pyk-2 in LPL−/− B cells. (A, B) Immunoblot using phospho-specific antibodies for phosphorylated (A) Pyk-2 or (B) ERK of post-nuclear lysates generated from purified WT or LPL−/− B cells stimulated with either the F(ab')2 fragment of goat anti-mouse IgM (10 μg/ml, 5 min) or CXCL12 (100 ng/ml, 2 min). Total protein levels were assessed by immunoblot for total Pyk-2, or total ERK. Ratios of phosphorylated protein:total protein in stimulated cells, normalized to the ratio of phosphorylated protein:total protein in unstimulated cells, is given below each lane. Normalized ratios from replicate experiments are depicted in bar graphs below each immunoblot. Data shown as mean ± SEM, p-value determined by Mann-Whitney test, n = 4 for phospho-Pyk-2 and n=3 for phospho-ERK. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of the upregulation of the activation markers CD69 and CD86 following stimulation of WT and LPL−/− B cells on plate-bound anti-IgM (10 μg/ml). Representative of two independent experiments. (D) CFSE dilution of WT and LPL−/− B cells unstimulated or stimulated with soluble F(ab')2 fragment of goat anti-mouse IgM (10 μg/ml) and rIL-4 (10 ng/ml) for 72 h.

To determine if LPL is required for activation signaling through IgM, splenocytes from WT and LPL−/− mice were stimulated overnight on plate-bound IgM. B cells from LPL−/− mice upregulated CD69 and CD86 to a slightly greater extent than B cells from WT mice (Fig. 6C). Splenic B cells isolated from LPL−/− mice also underwent proliferation in response to stimulation through soluble anti-IgM and IL-4, though the percentage of proliferating cells was slightly reduced compared to that of WT B cells (Fig. 6D). Thus, proximal IgM signaling appeared largely intact in LPL−/− B cells, though there may be a subtle alteration in signaling outcomes.

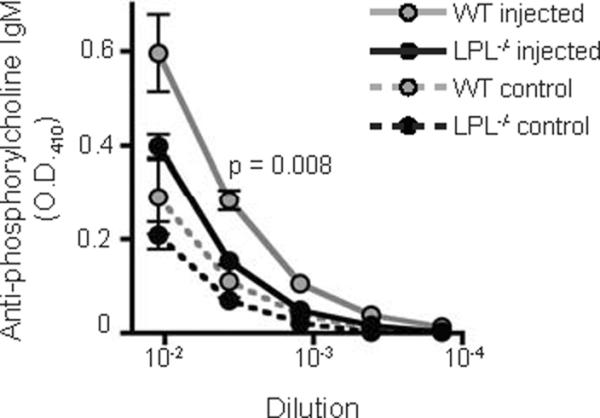

Reduced immunty of LPL−/− mice to Streptococcus pneumoniae

MZ B cells are critical to the generation of a rapid humoral response to bloodborne, polysaccharide organisms (17). Given that MZ B cells are greatly diminished in LPL−/− mice, we predicted a functional deficit of LPL−/− mice in responding to bloodborne, T-independent, polysaccharide antigens. We tested this prediction through measuring antibody titers generated against the pneumococcal cell wall component, phosphorylcholine, in response to i.v. injection of heat-killed S. pneumoniae. The increase in anti-phosphorylcholine IgM was reduced in challenged LPL−/− mice (Fig. 7). Thus, LPL−/− mice demonstrate a functional immunodeficiency predicted by the loss of MZ B cells.

Figure 7.

Decreased IgM response to heat-killed S. pneumoniae. Serum anti-phosphorylcholine IgM antibody titers were determined by ELISA five days after i.v. challenge with heat-killed S. pneumoniae of WT (grey circles) and LPL−/− (filled circles) mice. Data shown as mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments (n = 5 mice injected with heat-killed S. pneumoniae, indicated by solid line; n = 3 uninjected control mice, indicated by dashed line), p-value of titers at 1:270 dilution determined by Mann-Whitney test.

Discussion

Here we demonstrate the requirement for the actin-bundling protein LPL in splenic maturation of B cells. LPL−/− mice have significantly reduced numbers of splenic FO and MZ B cells, despite normal bone marrow development and apparently normal splenic entry of immature B cells. Furthermore, B cell entry into the lymph nodes and bone marrow was partially impaired by LPL-deficiency. Splenic B cell development and lymphoid organ entry are both regulated by chemokine receptor signaling. Normal chemokine-mediated motility of B cells required LPL. Furthermore, the addition of an integrin ligand to the transwell assay did not promote the transmigration of LPL−/− cells as it did for WT cells. Interestingly, MZ B cells that did develop in LPL−/− mice appeared less dependent upon LPL for CXCL12- and CXCL13-induced motility than did newly-forming and FO splenic B cell subsets. A diminished requirement for LPL in chemokine-mediated motility in MZ B cells from LPL−/− mice may represent selection bias, in that only those developing B cells able to migrate in the absence of LPL were selected to populate the MZ B cell niche. MZ B cells did, however, require LPL for migration towards S1P, a chemoattractant critical for MZ B cell development (19). Also, like newly-forming and FO splenic B cells, MZ B cells required LPL for normal chemokine-mediated transmigration in the presence of integrin ligand. LPL was not required for chemokine-mediated activation of integrin adhesion in any splenic B cell subset. The activity of LPL in motility therefore seems to be similar to that of Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein (WASP), in that deficiency of these proteins impairs motility without impacting adhesion (38). The observation that integrin ligation does not enhance the transmigration of LPL−/− cells, despite normal adhesion, suggests a critical role for LPL in the convergence of chemokine and integrin contributions to the transmigration of lymphocytes.

Chemokine receptor signaling pathways that regulate lymphocyte motility and adhesion have been extensively reviewed (3, 39). In brief, chemoattractants bind to G-protein-coupled seven-transmembrane receptors. Binding triggers calcium flux, activates src-family kinases and other kinases such as ERK, Akt, p38, and Pyk-2, and recruits small GTP-binding proteins such as Rho, Rac, and Rap. Activation of the small GTP-binding proteins requires the recruitment of guanine nucleotide exchange factors, such as Dock2 and Dock8. The plethora of activated signaling molecules combine to trigger changes in cell shape, polarity, and adhesion, which promote cellular motility. Changes in shape, polarity and adhesion require dynamic rearrangements in the actin cytoskeleton that are enabled by multiple actin-binding proteins, such as WASP and coronin. Specific deficiencies in these proteins lead to diminshed chemotaxis and impaired B cell development (17, 22–25, 40, 41). While many individual elements of chemokine signaling have been identified, a thorough understanding of interactions between different components has remained elusive. A comparison of B cell development in LPL−/− mice to B cell development in other mice genetically deficient for molecules required for chemotaxis, adhesion or transmigration should further elucidate signaling pathways unique to each process.

Early bone marrow development of B cells depends upon CXCL12 and its receptor, CXCR4. CXCR4 and CXCL12 localize B cell precursors to specific bone marrow niches. Despite deficient motility towards CXCL12, early B cell development in the bone marrow of LPL−/− mice appeared unaffected, as assessed by flow cytometric analysis of B cell subsets in WT and LPL−/− mice, analysis of competitive bone marrow chimeras, and BrdU incorporation to determine turnover of bone marrow subsets. Both integrin-mediated adhesion and chemotaxis were reduced in Rap1B−/− B cells, and early bone marrow development was impaired in Rap1B−/−mice (23). The normal B cell development we observed in the bone marrow of LPL−/− mice argues that CXCR4-induced motility or transmigration is dispensable for early bone marrow development, while CXCR4-induced adhesion is required. This argument correlates with prior observations that CXCR4 signaling upregulates the adhesiveness of pro- and pre-B cells for VCAM-1 (12). Thus, the dominant function of CXCR4 within the bone marrow compartment for early B cell development may be the promotion of adhesion.

After progressing to the immature B cell stage, developing B cells move from the bone marrow to the spleen via the bloodstream. Normal emigration of immature B cells from the bone marrow in LPL−/− mice is suggested by normal turnover of B cells subsets (Fig. 1E), as diminished emigration of immature B cells has been shown to result in reduced turnover of the immature B cell subset (15). Normal emigration of immature B cells appears to occur in LPL−/−mice despite a requirement for LPL in S1P-mediated motility, again suggesting that a downstream function of the chemoattractant receptor other than induction of motility, such as the promotion of changes in adhesion or effects upon signaling through CXCR4, is required for maturation and egress of bone marrow B220+ cells (13, 42). Alternatively, the residual motility of LPL−/− bone marrow B220+ cells may be sufficient to permit normal bone marrow maturation and egress.

Normal splenic entry by LPL−/− immature B cells is implied by the normal number of immature B cells in the spleens of LPL−/− mice (Fig 2D) and directly demonstrated through cotransfer experiments (Fig 5A). These results suggest that chemokine-mediated transmigration is not required for splenic entry. This conclusion is supported by the analysis of mice deficient for both Rac1 and Rac2, in which immature B cells are defective in both chemotaxis and adhesion. Immature Rac1/Rac2−/− B cells also enter the spleen normally, demonstrating that neither the movement of immature B cells from the bone marrow to the blood, nor from the blood into the spleen, requires intact chemotaxis (25). B cell development in LPL−/− mice proceeds unimpeded until the immature B cells enter the spleen.

After splenic entry, developing B cells cross the marginal sinus lining cells into the splenic white pulp, where a majority mature into FO B cells and a small number differentiate into MZ B cells. MZ B cells require additional chemotactic and adhesive cues to remain appropriately localized in the marginal zone (11). Deficiencies of various regulators of chemotaxis or adhesion impair different stages of splenic B cell development, suggesting a high degree of complexity in the regulation of B cell movement through splenic compartments during maturation. Rac1/Rac2−/− B cells cannot enter the splenic white pulp, and are therefore suspended in an early transitional stage (25). Rap1B−/− B cells generate normal numbers of FO and T2 but diminished numbers of MZ B cells, suggesting that Rap1B is not required for the initial crossing of the marginal sinus, but is necessary for the localization of either MZ B cells or MZ B cell precursors. Talin1-deficiency, which disrupts integrin-mediated adhesion but not chemotaxis, impairs MZ B cell development but not maturation of T1, FO and T2 B cells. These different models of deficiency suggest a maturation process in which there are no barriers to restrict splenic entry of immature B cells, but at least two barriers regulate maturation of MZ B cells. First, transitional B cells must migrate into the splenic white pulp to mature into FO and T2 cells (25). Second, MZ precursor or MZ B cells must cross out of the white pulp and reside in the splenic marginal zone (33). LPL deficiency partially blocks FO B cell development and severely, though not completely, blocks MZ B cell development. Furthermore, BrdU incorporation suggested slightly reduced turnover of the earliest T1 splenic subset, consistent with diminished maturation of this stage (Fig. 2F). The simplest explanation is that the combined chemotactic and integrin signals enabling lymphocyte transmigration across barriers are partially dependent upon LPL. Thus LPL−/− B cells are partially inhibited both in entering the white pulp, resulting in the decrease in FO B cell maturation, and further inhibited in migrating to the marginal zone, resulting in the loss of MZ B cells.

A requirement for LPL in lymphocyte transmigration also explains the competitive defect in entry of LPL−/− B cells into lymph nodes and bone marrow. Lymph node entry occurs via high endothelial venules. Lymphatic endothelial cells present a variety of adhesive and chemokine cues, including CD62L ligand, CCL21, and the lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (43, 44). Mature FO B cells recirculate to the bone marrow and reside in perisinusoidal niches (45). Lymphocytes must respond to the appropriate chemotactic and adhesive cues, then cross the cellular barriers into the lymph nodes or perisinusoidal niches. Lymphocytes from mice deficient for proteins required for chemotaxis or adhesion, such as talin1, Dock2, or CasL, are impaired in lymph node entry (40, 44, 46). We found increased B cells in the blood of LPL−/−mice (Fig. 4A), and LPL−/− B cells were at a competitive disadvantage in entering both lymph nodes and the bone marrow in co-transfer assays (Fig. 5A). The observation that there is no decrease in the number of B cells present in the lymph nodes or bone marrow of LPL−/− mice may be due to an inability of LPL−/− B cells to egress from these sites, though this possibility has not yet been formally tested.

We have further advanced our understanding of the the mechanism by which LPL promotes B lymphocyte transmigration through the observation that Pyk-2 levels are decreased in LPL−/− B cells, relative to the expression of the critical kinase ERK. We also found that phosphorylation of Pyk-2 upon stimulation of CXCR4, and to a lesser extent, IgM, is diminished in LPL−/− B cells. The tyrosine kinase Pyk-2 is homologous to focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Pyk-2 is activated in response to a variety of adhesive, chemotactic, and antigen receptor stimuli (17, 47–50). Phosphorylation of tyrosine residue 402 of Pyk-2 enables kinase activation and the recruitment of src family kinases (50). Pyk-2 deficiency results in diminished chemotaxis and impaired MZ B cell development (17). Interestingly, Pyk-2 phosphorylation was not inhibited in LPL−/− PMNs stimulated through integrin adhesion, indicating a different role for LPL in neutrophils than in lymphocytes (7). LPL deficiency did not appear to significantly impact the activation of the kinase ERK, indicating that the effect of LPL deficiency on Pyk-2 activity is specific. The mechanism by which the activity of an actin-bundling like LPL regulates the level and phosphorylation of the kinase Pyk-2 remains an area of active investigation. As Pyk-2 is known to be required for normal lymphocyte motility, the diminshed levels and activation of Pyk-2 in LPL−/− B cells offers a molecular explanation for the motility deficit of LPL−/−lymphocytes.

While LPL is clearly required for chemokine-mediated motility and transmigration, LPL is dispensable for several outcomes of chemokine signaling. As discussed, the chemokine-mediated increase in integrin adhesion is intact in LPL−/− cells (Fig. 5D, 5E). ERK activation downstream of chemokine stimulation is intact in LPL−/− B cells (Fig. 6B). Also, T and B cell zones are clearly separated in LPL−/− splenic sections, indicating that the functions of chemokine receptors required for maintaining T and B cell zones do not depend upon LPL (Fig. 3A). Increasing the concentration of chemokine did not enhance motility of LPL−/− B cells (Fig S1C), suggesting that LPL deficiency does not reduce the sensitivity of developing B cells to chemokine. Finally, transwell experiments indicate that the baseline motility of LPL−/− B cells is reduced as well as chemokine-mediated motility, such that the fold-increase over control in migration can appear similar between WT and LPL−/− B cells. Combined, these results indicate that LPL is required specifically for the recruitment of the cellular machinery needed for motility, but not for the initial receptor engagement of chemokine or other chemokine-mediated signaling or functions.

Assessment of IgM signaling in LPL−/− B cells did not reveal a severe block in anti-IgM-mediated upregulation of activation markers or proliferation, indicating that IgM signaling in LPL−/− B cells is largely intact. There was a slight increase in the expression of activation markers on anti-IgM-stimulated LPL−/− B cells, and a slight decrease in the anti-IgM-mediated proliferation of LPL−/− B cells, suggesting a subtle alteration in the outcome of IgM signaling in LPL−/− B cells. It is possible that this slight decrease in anti-IgM-mediated proliferation contributed to the diminished BrdU incorporation of T1 B cells in LPL−/− mice. We did not find statistically significant decreases in phosphorylation of Pyk-2, ERK, or p38 following IgM engagement on LPL−/− B cells. However, the possibility that the reduction of total Pyk-2 levels in LPL−/− B cells altered the outcome of IgM signaling has not been excluded.

By virtue of their localization at the border of the splenic marginal zone with the splenic red pulp, MZ B cells are among the first immune cells to contact blood-borne antigens (21). MZ B cells are critical to the rapid response to T-independent, polysaccharide antigens (17, 51). Immunity to the Gram positive bacterium S. pneumoniae depends upon the ability to generate antibodies to polysaccharide antigens. A reduced humoral response to i.v. injection with heat-killed S. pneumoniae in LPL−/− mice correlated with diminished numbers of MZ B cells (Fig. 7). Whether a deficient humoral response to S. pneumoniae leads to increased susceptibility of LPL−/− mice to penumococcal infection is under study.

In summary, the actin-bundling protein LPL is required for B lymphocyte motility towards chemokines, and for the integrin-associated enhancement of chemokine-induced transwell migration. LPL is dispensable for integrin-mediated adhesion. Deficiency of LPL results in diminished protein levels and activation of the tyrosine kinase Pyk-2, which is required for normal lymphoycte migration. Defective motility of LPL−/− B cells results in diminished splenic maturation of B cells, with a significant defect in maturation of MZ B cells. A loss of MZ B cells leads to an inability to respond to blood-borne polysaccharide antigens, such as S. pneumoniae. LPL is a critical regulator of B lymphocyte motility and thus of splenic B lymphocyte development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Paul M. Allen, Eric J. Brown, Phil Tarr and Mary Dinauer for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Darren Kreamelmeyer for technical assistance with maintenance of the mouse colony.

This work was supported by the Children's Discovery Institute (MD-FR-2010-83) (SCM), by the NIH grant K08AI081751-01 (SCM), and by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society-St. Jude's Award for Basic Research (SCM). SCM is a Scholar of the Child Health Research Center of Excellence in Developmental Biology at Washington University School of Medicine (K12-HD01487).

Footnotes

3Abbreviations used: L-plastin (LPL), wild-type (WT), marginal zone (MZ), follicular (FO), allophycocyanin (APC), Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein (WASP), sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P).

References

- 1.Vicente-Manzanares M, Sanchez-Madrid F. Role of the cytoskeleton during leukocyte responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:110–122. doi: 10.1038/nri1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez TS, Billadeau DD. T cell activation and the cytoskeleton: you can't have one without the other. Adv. Immunol. 2008;97:1–64. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)00001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thelen M, Stein JV. How chemokines invite leukocytes to dance. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:953–959. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morley SC, Wang C, Lo WL, Lio CW, Zinselmeyer BH, Miller MJ, Brown EJ, Allen PM. The actin-bundling protein L-plastin dissociates CCR7 proximal signaling from CCR7-induced motility. J. Immunol. 2010;184:3628–3638. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C, Morley SC, Donermeyer D, Peng I, Lee WP, Devoss J, Danilenko DM, Lin Z, Zhang J, Zhou J, Allen PM, Brown EJ. Actin-bundling protein L-plastin regulates T cell activation. J. Immunol. 2010;185:7487–7497. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delanote V, Vandekerckhove J, Gettemans J. Plastins: versatile modulators of actin organization in (patho)physiological cellular processes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005;26:769–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Mocsai A, Zhang H, Ding RX, Morisaki JH, White M, Rothfork JM, Heiser P, Colucci-Guyon E, Lowell CA, Gresham HD, Allen PM, Brown EJ. Role for plastin in host defense distinguishes integrin signaling from cell adhesion and spreading. Immunity. 2003;19:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cyster JG. Chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:127–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forster R, Mattis AE, Kremmer E, Wolf E, Brem G, Lipp M. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell. 1996;87:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Takakura N, Nishikawa S, Kitamura Y, Yoshida N, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature. 1996;382:635–638. doi: 10.1038/382635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allman D, Pillai S. Peripheral B cell subsets. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008;20:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagasawa T. The chemokine CXCL12 and regulation of HSC and B lymphocyte development in the bone marrow niche. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007;602:69–75. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72009-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allende ML, Tuymetova G, Lee BG, Bonifacino E, Wu YP, Proia RL. S1P1 receptor directs the release of immature B cells from bone marrow into blood. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1113–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan EE, Pelanda R, Torres RM. S1P3 confers differential S1P-induced migration by autoreactive and non-autoreactive immature B cells and is required for normal B-cell development. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010;40:688–698. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira JP, Xu Y, Cyster JG. A role for S1P and S1P1 in immature-B cell egress from mouse bone marrow. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ansel KM, Ngo VN, Hyman PL, Luther SA, Forster R, Sedgwick JD, Browning JL, Lipp M, Cyster JG. A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles. Nature. 2000;406:309–314. doi: 10.1038/35018581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guinamard R, Okigaki M, Schlessinger J, Ravetch JV. Absence of marginal zone B cells in Pyk-2-deficient mice defines their role in the humoral response. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:31–36. doi: 10.1038/76882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopes-Carvalho T, Foote J, Kearney JF. Marginal zone B cells in lymphocyte activation and regulation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2005;17:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cinamon G, Matloubian M, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Low C, Lu T, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 promotes B cell localization in the splenic marginal zone. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:713–720. doi: 10.1038/ni1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan JB, Xu K, Cretegny K, Visan I, Yuan JS, Egan SE, Guidos CJ. Lunatic and manic fringe cooperatively enhance marginal zone B cell precursor competition for delta-like 1 in splenic endothelial niches. Immunity. 2009;30:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin F, Kearney JF. Marginal-zone B cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nri799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Yu M, Podd A, Wen R, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, White GC, Wang D. A critical role of Rap1b in B-cell trafficking and marginal zone B-cell development. Blood. 2008;111:4627–4636. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu H, Awasthi A, White GC, 2nd, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Malarkannan S. Rap1b regulates B cell development, homing, and T cell-dependent humoral immunity. J. Immunol. 2008;181:3373–3383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randall KL, Lambe T, Johnson AL, Treanor B, Kucharska E, Domaschenz H, Whittle B, Tze LE, Enders A, Crockford TL, Bouriez-Jones T, Alston D, Cyster JG, Lenardo MJ, Mackay F, Deenick EK, Tangye SG, Chan TD, Camidge T, Brink R, Vinuesa CG, Batista FD, Cornall RJ, Goodnow CC. Dock8 mutations cripple B cell immunological synapses, germinal centers and long-lived antibody production. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:1283–1291. doi: 10.1038/ni.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson RB, Grys K, Vehlow A, de Bettignies C, Zachacz A, Henley T, Turner M, Batista F, Tybulewicz VL. A novel Rac-dependent checkpoint in B cell development controls entry into the splenic white pulp and cell survival. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:837–853. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira JP, An J, Xu Y, Huang Y, Cyster JG. Cannabinoid receptor 2 mediates the retention of immature B cells in bone marrow sinusoids. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:403–411. doi: 10.1038/ni.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mobley JL, Shimizu Y. Measurement of cellular adhesion under static conditions. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2001:28. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0728s37. Chapter 7:Unit 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Gorter DJ, Reijmers RM, Beuling EA, Naber HP, Kuil A, Kersten MJ, Pals ST, Spaargaren M. The small GTPase Ral mediates SDF-1-induced migration of B cells and multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2008;111:3364–3372. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herroeder S, Reichardt P, Sassmann A, Zimmermann B, Jaeneke D, Hoeckner J, Hollmann MW, Fischer KD, Vogt S, Grosse R, Hogg N, Gunzer M, Offermanns S, Wettschureck N. Guanine nucleotide-binding proteins of the G12 family shape immune functions by controlling CD4+ T cell adhesiveness and motility. Immunity. 2009;30:708–720. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tung JW, Parks DR, Moore WA, Herzenberg LA. Identification of B-cell subsets: an exposition of 11-color (Hi-D) FACS methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;271:37–58. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-796-3:037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Muller I, Wolf E, Lipp M. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray A, Dittel BN. Isolation of mouse peritoneal cavity cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2010;35:1488. doi: 10.3791/1488. doi: 10.3791/1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu TT, Cyster JG. Integrin-mediated long-term B cell retention in the splenic marginal zone. Science. 2002;297:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.1071632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imhof BA, Aurrand-Lions M. Adhesion mechanisms regulating the migration of monocytes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:432–444. doi: 10.1038/nri1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glodek AM, Le Y, Dykxhoorn DM, Park SY, Mostoslavsky G, Mulligan R, Lieberman J, Beggs HE, Honczarenko M, Silberstein LE. Focal adhesion kinase is required for CXCL12-induced chemotactic and pro-adhesive responses in hematopoietic precursor cells. Leukemia. 2007;21:1723–1732. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woolf E, Grigorova I, Sagiv A, Grabovsky V, Feigelson SW, Shulman Z, Hartmann T, Sixt M, Cyster JG, Alon R. Lymph node chemokines promote sustained T lymphocyte motility without triggering stable integrin adhesiveness in the absence of shear forces. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1076–1085. doi: 10.1038/ni1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kehrl JH. Chemoattractant receptor signaling and the control of lymphocyte migration. Immunol. Res. 2006;34:211–227. doi: 10.1385/IR:34:3:211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westerberg LS, de la Fuente MA, Wermeling F, Ochs HD, Karlsson MC, Snapper SB, Notarangelo LD. WASP confers selective advantage for specific hematopoietic cell populations and serves a unique role in marginal zone B-cell homeostasis and function. Blood. 2008;112:4139–4147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kehrl JH, Hwang IY, Park C. Chemoattract receptor signaling and its role in lymphocyte motility and trafficking. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009;334:107–127. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-93864-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukui Y, Hashimoto O, Sanui T, Oono T, Koga H, Abe M, Inayoshi A, Noda M, Oike M, Shirai T, Sasazuki T. Haematopoietic cell-specific CDM family protein DOCK2 is essential for lymphocyte migration. Nature. 2001;412:826–831. doi: 10.1038/35090591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moratz C, Hayman JR, Gu H, Kehrl JH. Abnormal B-cell responses to chemokines, disturbed plasma cell localization, and distorted immune tissue architecture in Rgs1−/− mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:5767–5775. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5767-5775.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimura T, Boehmler AM, Seitz G, Kuci S, Wiesner T, Brinkmann V, Kanz L, Mohle R. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonist FTY720 supports CXCR4-dependent migration and bone marrow homing of human CD34+ progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;103:4478–4486. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mueller SN, Germain RN. Stromal cell contributions to the homeostasis and functionality of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:618–629. doi: 10.1038/nri2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manevich-Mendelson E, Grabovsky V, Feigelson SW, Cinamon G, Gore Y, Goverse G, Monkley SJ, Margalit R, Melamed D, Mebius RE, Critchley DR, Shachar I, Alon R. Talin1 is required for integrin-dependent B lymphocyte homing to lymph nodes and the bone marrow but not for follicular B cell maturation in the spleen. Blood. 2010;116:5907–5918. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-293506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cariappa A, Mazo IB, Chase C, Shi HN, Liu H, Li Q, Rose H, Leung H, Cherayil BJ, Russell P, von Andrian U, Pillai S. Perisinusoidal B cells in the bone marrow participate in T-independent responses to blood-borne microbes. Immunity. 2005;23:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seo S, Asai T, Saito T, Suzuki T, Morishita Y, Nakamoto T, Ichikawa M, Yamamoto G, Kawazu M, Yamagata T, Sakai R, Mitani K, Ogawa S, Kurokawa M, Chiba S, Hirai H. Crk-associated substrate lymphocyte type is required for lymphocyte trafficking and marginal zone B cell maintenance. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3492–3501. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma EA, Lou O, Berg NN, Ostergaard HL. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes express a beta3 integrin which can induce the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and the related PYK-2. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:329–335. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Durand CA, Westendorf J, Tse KW, Gold MR. The Rap GTPases mediate CXCL13- and sphingosine1-phosphate-induced chemotaxis, adhesion, and Pyk2 tyrosine phosphorylation in B lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36:2235–2249. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tse KW, Dang-Lawson M, Lee RL, Vong D, Bulic A, Buckbinder L, Gold MR. B cell receptor-induced phosphorylation of Pyk2 and focal adhesion kinase involves integrins and the Rap GTPases and is required for B cell spreading. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:22865–22877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Collins M, Bartelt RR, Houtman JC. T cell receptor activation leads to two distinct phases of Pyk2 activation and actin cytoskeletal rearrangement in human T cells. Mol. Immunol. 2010;47:1665–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin F, Oliver AM, Kearney JF. Marginal zone and B1 B cells unite in the early response against T-independent blood-borne particulate antigens. Immunity. 2001;14:617–629. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.