Abstract

The repair and regeneration of large bone defects resulting from disease or trauma remains a significant clinical challenge. Bioactive glass has appealing characteristics as a scaffold material for bone tissue engineering, but the application of glass scaffolds for the repair of load-bearing bone defects is often limited by their low mechanical strength and fracture toughness. This paper provides an overview of recent developments in the fabrication and mechanical properties of bioactive glass scaffolds. The review reveals the fact that mechanical strength is not a real limiting factor in the use of bioactive glass scaffolds for bone repair, an observation not often recognized by most researchers and clinicians. Scaffolds with compressive strengths comparable to those of trabecular and cortical bones have been produced by a variety of methods. The current limitations of bioactive glass scaffolds include their low fracture toughness (low resistance to fracture) and limited mechanical reliability, which have so far received little attention. Future research directions should include the development of strong and tough bioactive glass scaffolds, and their evaluation in unloaded and load-bearing bone defects in animal models.

Keywords: bioactive glass, bone tissue engineering, scaffolds, fracture toughness, mechanical strength

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

In the last two decades, tissue engineering has emerged as a promising approach for the repair and regeneration of tissues and organs lost or damaged as a result of traumatic injuries, disease, or aging [1, 2]. Tissues such as skin [3–6], bone [7–9], and cartilage [10, 11] have been successfully regenerated (produced?). The approach has the potential to overcome the problem of a shortage of living tissues and organs available for transplantation. There are over 6.2 million bone fractures in the U. S. each year, and 10% fail to heal properly due to non-union or delayed union [12]. Osteoporosis currently affects 10 million people, and it is projected to increase to 14 million by 2020, resulting in health care costs of over $25 billion per year [13]. Worldwide, an estimated 2.2 million bone graft procedures are performed annually to promote fracture healing, fill defects, or repair spinal lesions [14].

Autografts are the gold standard for treatment of bone defects but limited supply and donor site morbidity are significant problems [15]. Bone allografts are alternatives to autografts but they are expensive, and suffer from potential risks such as disease transmission and adverse host immune response. Synthetic biomaterials would be ideal bone substitutes, but the clinical success of procedures performed with available synthetic biomaterials does not currently approach that for autologous bone. Most implants for bone replacement or fracture repair in load-bearing situations are made from strong materials selected to provide mechanical support, such as the Ti6Al4V or Co-Cr alloys used in total joint or knee replacement or plates and screws for the repair of fractures in the long bones or craniofacial region. Metallic implants have well-documented fixation problems [16–18], and unlike natural bone, cannot self-repair or adapt to changing physiological conditions [19]. They are stronger and stiffer than bone and promote bone resorption by shielding the surrounding skeleton from its normal stress levels. As a consequence, the implant becomes loose over time [20, 21].

The shortcomings of current treatments and the impact on health care costs have motivated interest in the engineering of new bone substitutes. Critical to bone tissue engineering is the scaffold, a porous structure that, ideally, must guide new tissue formation by supplying a matrix with interconnected porosity and tailored surface chemistry for cell growth and proliferation and the transport of nutrients and metabolic waste [22]. Designing the ideal scaffold means balancing the need for large interconnected porosity for tissue ingrowth, nutrient transport, and angiogenesis while controlling resorption rates and the required mechanical properties (e.g., stiffness, strength, and fracture resistance) [22–28]. These characteristics are often coupled, resulting in the difficulties in design, characterization and translation of the synthetic implants to clinical applications.

1.2 Scaffolds for bone tissue engineering

Currently, there are no clear design criteria for the mechanical properties of scaffolds intended for bone repair, particularly those to be used in load-bearing defects. It is often stated that the scaffolds should mimic the morphology, structure and function of bone in order to optimize integration with surrounding tissues [22, 29, 30]. The variability in the architecture and mechanical properties of bone, coupled with differences in age, nutritional state, activity (mechanical loading) and disease status of individuals, provide a major challenge in the design and fabrication of scaffolds for specific defect sites. Bone is generally classified into two types: cortical bone, also referred to as compact bone, and trabecular bone, also referred to as cancellous or spongy bone (Fig. 1) [31]. The mechanical properties of bone vary between subjects, from one to another, and within different regions of the same bone. Table 1 summarizes the compressive, flexural and tensile strength, elastic modulus and porosities of both trabecular and cortical bones for reference [32–40]. Although the requisite mechanical properties of scaffolds for bone repair are still the subject of debate, it is believed that their initial mechanical strength should withstand subsequent changes resulting from degradation and tissue ingrowth in the in vivo bone environment [30].

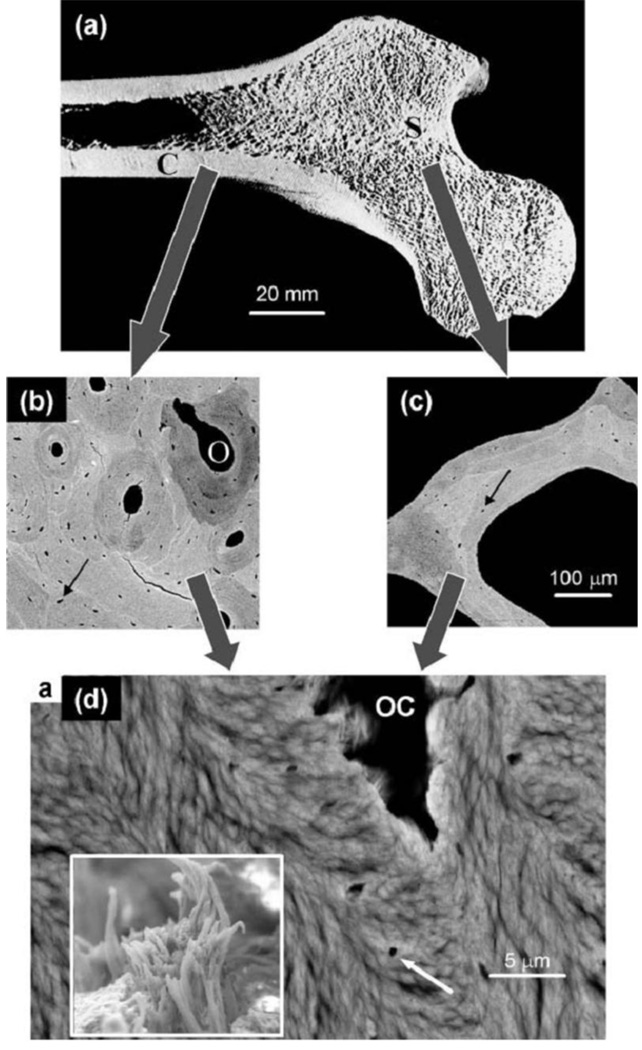

Figure 1.

Hierarchical structure of bone in the human femur. (a) Section through a femur head showing the shell of cortical (compact) bone (C) and the trabecular (spongy or cancellous) bone (S) inside. (b) Back scattered electron (BSE) image of cortical bone, revealing osteons (O) corresponding to blood vessels surrounded by concentric layers of bone materials. (C) BSE image of a single trabeculae from the trabecular bone region. The arrows in both (b) and (c) indicate osteocyte lacunae where bone cells have previously been living. (d) Further enlargement showing the lamellar and fibrillar material texture around an osteocyte lacuna (OC) as visible in scanning electron microscopy (see white arrow). The lamellae are formed by bundles of mineralized collagen fibrils (insert). (From Ref. 31)

Table 1.

Summary of the mechanical properties of human bone

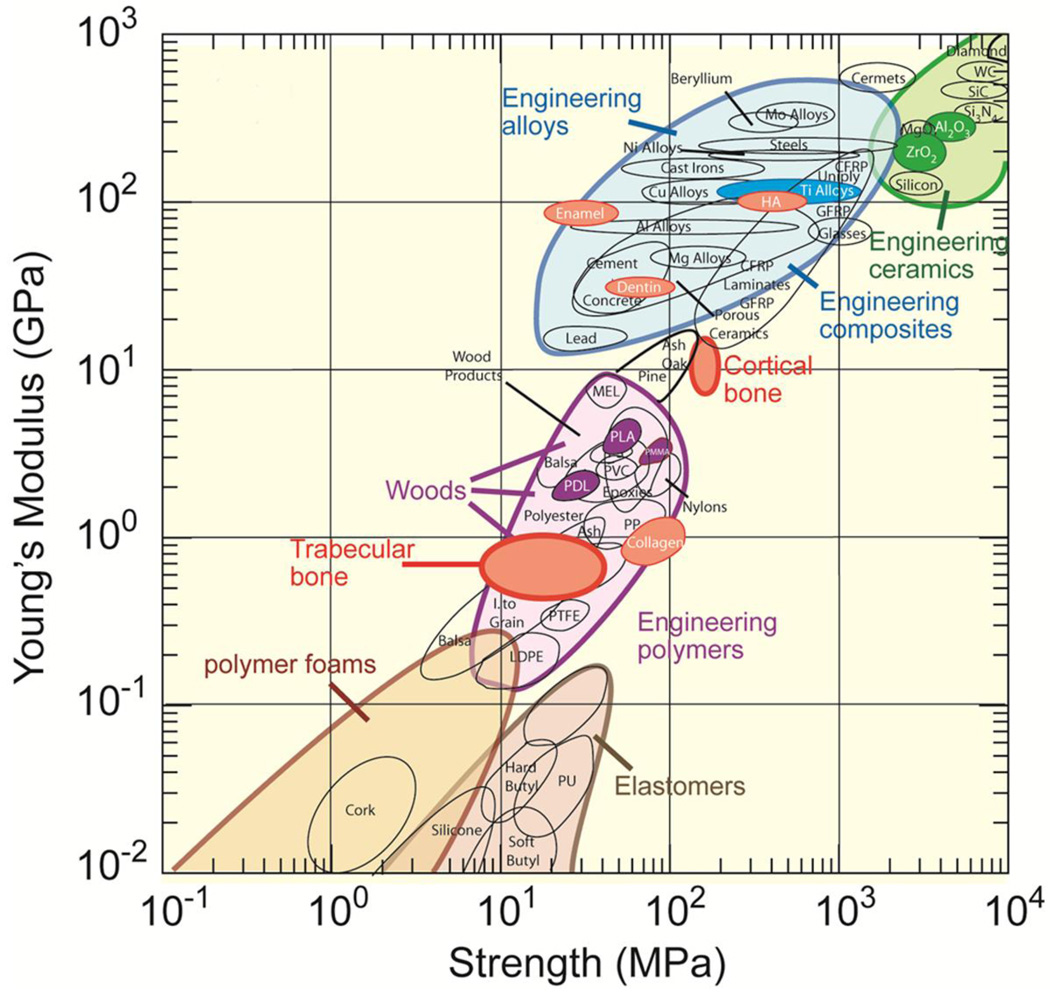

The properties of scaffolds depend primarily on the composition and microstructure of the materials. Figure 2 shows material property chart depicting strength and elastic modulus of natural and synthetic materials (typically with a dense microstructure containing no porosity) [41]. The mechanical response of bone is not matched by the biodegradable polymers, ceramics, or alloys currently used in orthopedic applications, yet, scaffolds for tissue engineering are commonly constructed from these materials. There are two kinds of biodegradable polymer materials: synthetic, and naturally derived [42–47]. For the regeneration of load-bearing bones, the use of biodegradable polymer scaffolds is challenging because of their low mechanical strength. Attempts have been made to reinforce the polymers with a biocompatible inorganic phase, commonly hydroxyapatite (HA) [30, 48, 49], but the success of that approach is uncertain. Brittle, scaffolds fabricated from inorganic materials such as calcium phosphate-based bioceramics and bioactive glass can provide higher mechanical strength than polymeric scaffolds. There is an increasing interest in creating and evaluating scaffolds of these materials and the fabrication and properties of the calcium phosphate based bioceramics have been extensively studied and reviewed in the literature [30, 50–53].

Figure 2.

Material property chart showing Young’s modulus vs. strength (From Ref. 41)

1.3 Bioactive glass scaffolds

Since the discovery of 45S5 bioactive glasses by Hench [54], they have been frequently considered as scaffold materials for bone repair [54–57]. Bioactive glasses have a widely recognized ability to foster the growth of bone cells [58, 59], and to bond strongly with hard and soft tissue [54, 55]. Upon implantation, bioactive glasses undergo specific reactions, leading to the formation of an amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) or crystalline hydroxyapatite (HA) phase on the surface of the glass, which is responsible for their strong bonding with the surrounding tissue [55]. Bioactive glasses are also reported to release ions that activate expression of osteogenic genes [60, 61], and to stimulate angiogenesis [62–64].

The advantages of the glasses are ease in controlling chemical composition and, thus, the rate of degradation which make them attractive as scaffold materials. The structure and chemistry of glasses can be tailored over a wide range by changing either composition, or thermal or environmental processing history. Therefore, it is possible to design glass scaffolds with variable degradation rates to match that of bone ingrowth and remodeling. A limiting factor in the use of bioactive glass scaffolds for the repair of defects in load-bearing bones has been their low strength [49, 56, 57]. Recent work has shown that by optimizing the composition, processing and sintering conditions, bioactive glass scaffolds can be created with predesigned pore architectures and with strength comparable to human trabecular and cortical bones [65, 66]. Another limiting factor of bioactive glass scaffolds has been the brittleness. This limitation has received little interest in the scientific community, judging from the paucity of publications that report on properties such as fracture toughness, reliability (i.e., Weibull modulus), or work of fracture of glass scaffolds.

This article presents an overview of current developments in the creation of bioactive glass scaffolds with the requisite structure and properties for bone tissue engineering, with a focus on their mechanical properties. We have organized the review in the following manner. First, we provide an overview of the fabrication techniques (methods) describing technologies that have been commonly used to produce bioactive glass scaffolds. The section titled “Mechanical properties of bioactive glass scaffolds” contains a detailed analysis of the strength, fracture toughness and toughening approaches, while the section on “in vitro and in vivo performance of bioactive glass scaffolds” presents a brief overview of the response of bioactive glass scaffolds to cells and tissues. We conclude with recommendations for future directions in the development of strong and reliable bioactive glass scaffolds.

2. Fabrication of bioactive glass scaffolds

In general, interconnected pores with a mean diameter (or width) of 100 µm or greater, and open porosity of >50% are considered to be the minimum requirements to permit tissue ingrowth and function in porous scaffolds [29, 67, 68]. A variety of methods have been used to fabricate bioactive glass scaffolds, including sol-gel, thermally bonding of particles, fibers or spheres, polymer foam replication, freeze casting, and solid freeform fabrication. A brief review of these fabrication techniques is presented next to give a general idea of the methodology.

2.1 Sol–gel processing

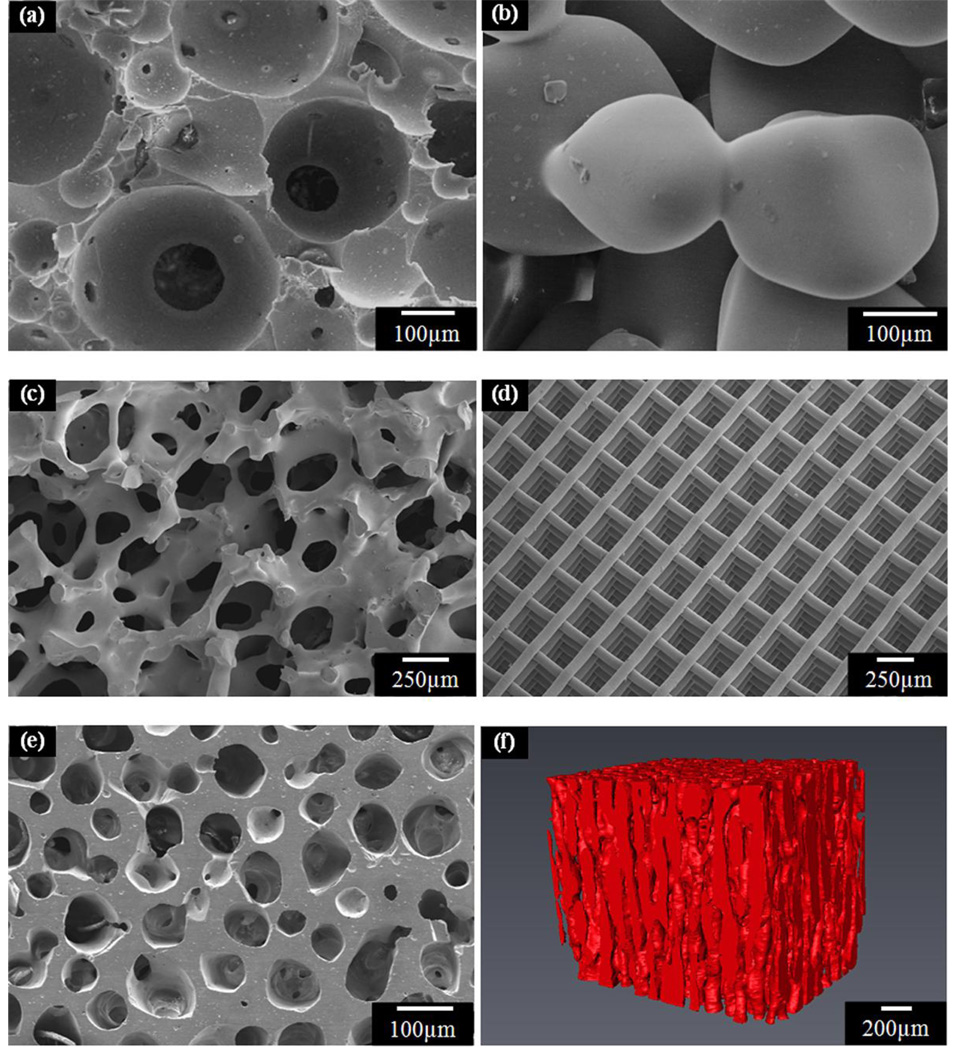

The preparation of bioactive glass scaffolds by the sol-gel process typically involves the foaming of a sol with the aid of a surfactant, followed by condensation and gelation reactions, as described for the glasses designated 58S and 70S30C [69–73]. The gel is then subjected to aging processes to strengthen it, drying to remove the liquid by-product, and sintering to form porous, three-dimensional scaffolds (Fig. 3a). The scaffolds have a hierarchical pore architecture, consisting of interconnected macropores (10–500 µm) resulting from the foaming process, and mesopores (2–50 nm) that are inherent to the sol–gel process. This hierarchical pore architecture is considered to be beneficial for stimulating the response of the scaffold to cells, because it mimics the hierarchical structure of natural tissues and more closely simulates a physiological environment. Because of the nanopores in the glass network, sol-gel derived scaffolds have high surface area (100–200 m2/g); as a result, these scaffolds degrade and convert faster to HA than scaffolds of melt-derived glass with the same composition. However, these sol-gel derived scaffolds have low strength (0.3–2.3 MPa) [72], and consequently they are suitable for substituting defects in low-load sites only.

Figure 3.

Microstructures of bioactive glass scaffolds created by a variety of processing methods: (a) sol-gel; (b) thermal bonding (sintering) of particles (microspheres); (c) ‘trabecular’ microstructure prepared by a polymer foam replication technique; (d) grid-like microstructure prepared by Robocasting; (e) oriented microstructure prepared by unidirectional freezing of suspensions (plane perpendicular to the orientation direction); (f) Micro-computed tomography image of the oriented scaffolds in (e).

2.2 Thermal bonding of particles or fibers

In this process, the scaffold is formed by thermally bonding a loose and random packing of particles (irregular or spherical in shape) or short fibers in a mold with the desired geometry (Fig. 3b) [74–84]. Bioactive glass scaffolds with a wide range of compositions (e.g., 45S5; A-W; 13–93) have been fabricated using this technique. In some studies, a porogen (such as NaCl, starch, or organic polymer particles) is mixed with the bioactive glass particles as a fugitive phase to increase the pore size and porosity of the scaffolds. The porogen is removed by leaching or decomposition after forming the scaffold, but prior to sintering. The technique offers the advantage of ease of fabrication without the need for complex machinery. However, the key disadvantage of the method is the poor pore interconnectivity at low porogen loading.

2.3 Polymer foam replication

The polymer foam replication method, first used many years ago to produce macroporous ceramics [85], has seen considerable use in recent years to create porous glass scaffolds. In this method, a synthetic (e.g., polyurethane, PU) or natural (e.g., coral; wood) foam is initially immersed in a ceramic suspension to obtain a uniform coating on the foam struts. After drying the coated foam, the polymer template and organic binders are burned out through careful heat treatment, typically between 300–600°C, and the glass struts are densified by sintering at 600–1000 °C, depending on the composition and particle size of the glass.

The polymer foam replication technique can provide a scaffold microstructure similar to that of dry human trabecular bone (Fig. 3c). Scaffolds of silicate, borosilicate, and borate bioactive glass have been prepared using this method [86–99]. The main advantage of this method is the production of highly porous glass scaffolds with open and interconnected porosity in the range 40–95%. However, the strength of the scaffold is low, typically in the range reported for trabecular bone, which limits its use to the repair of low-load bone sites.

2.4 Solid freeform fabrication

Solid freeform fabrication (SFF), also referred to as rapid prototyping or additive manufacturing, is a term to describe a group of techniques that can be used to manufacture objects in a layer-by-layer fashion from a computer-aided design (CAD) file, without the use of traditional tools such as dies or molds. The technique can be used to build scaffolds whose structure follows a predesigned architecture modeled on a computer. In that way, the scaffold architecture can be controlled and optimized to achieve the desired mechanical response, accelerate the bone-regeneration process, and guide the formation of bone with the anatomic cortical-trabecular structure [27]. Several SFF techniques have been used for scaffold fabrication, including: three-dimensional printing (3DP), fused deposition modeling (FDM), ink-jet printing, stereolithography (SL), selective laser sintering (SLS), and robocasting [27, 100].

Scaffolds with controlled internal architecture and interconnectivity are made with SFF from a variety of biomaterials including biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLGA; PCL), and calcium phosphate materials (e.g., HA; TCP), as well as composites of these two classes of materials (e.g., PLGA/TCP) [100–105]. The fabrication of composite scaffolds containing bioactive glass (e.g., PLA/45S5 glass; PCL/45S5 glass) using a robocasting SFF technique has been reported [103], but there is little information on the production of bioactive glass scaffolds using SFF methods. Recently, scaffolds of apatite-mullite glass-ceramics, 13–93, and 6P53B glasses have been manufactured using freeze extrusion, selective laser sintering and robocasting methods [65, 106, 107]. In the robocasting method, an aqueous paste of 6P53B bioactive glass powder is extruded through a fine nozzle in filamentary forms and deposited over the previous layer while maintaining the weight of the printed structures [65]. The technique enables precise manipulation of the three-dimensional architecture (Fig. 3d), and printing of lines as thin as 30 µm using micron-sized glass powders. The sintered glass scaffolds, with an anisotropic structure, show a compressive strength (136 MPa) comparable to human cortical bone, which indicates that these scaffolds have excellent potential for the repair and regeneration of load-bearing bone defects [65].

2.5 Freeze casting of suspensions

For the production of porous glass and ceramic scaffolds, the freeze casting route involves rapid freezing of colloidally-stable suspension of particles in a nonporous mold, and sublimation of the frozen solvent under cold temperatures in a vacuum. After drying, the porous constructs are sintered to remove the fine pores between the particles in the walls of the macropores, which results in an improvement in the mechanical strength. Directional freezing of the suspensions leads to growth of the ice in a preferred direction, resulting in the formation of porous scaffolds with an oriented microstructure. The technique has been used to produce porous polymer, glass, and ceramic scaffolds [66, 108–116]. A benefit of the oriented microstructure is higher scaffold strength in the direction of orientation, compared to the strength of a scaffold with a randomly oriented microstructure [117]. Hydroxyapatite scaffolds have shown unusually high compressive strength in the orientation direction, up to four times the value for similar materials with similar porosity but randomly arranged pores. These strengths allow their consideration for load-bearing applications. Both 45S5 and 13–93 glass scaffolds have been prepared using the technique [96, 111, 114]. However, oriented scaffolds prepared from aqueous suspensions typically have a lamellar microstructure, with a pore width in the range 10–40 µm that is considered to be too small to support tissue ingrowth.

It has been shown that the addition of an organic solvent such as 1,4-dioxane to the aqueous solvent) [97], or the use of an organic solvent such as camphene [66], results in a change of the lamellar microstructure to a columnar microstructure and an increase in the pore width. Bioactive glass (13–93) scaffolds with columnar microstructures and pore diameters of 100–150 µm have been prepared (Figs. 3e, 3f). In addition to their higher strength, these oriented bioactive glass scaffolds have shown the ability to support cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro, as well as tissue infiltration in vivo [114, 115].

3. Mechanical properties of bioactive glass scaffolds

While the mechanical properties of bioactive glass scaffolds have been widely reported in the literature, most studies have focused on the mechanical response in compression loading only, giving values of the compressive strength and, sometimes, the elastic modulus for selected deformation rates. However, other mechanical properties, such as flexural strength and modulus, fracture toughness (a measure of the ability to resist fracture when a crack is present), reliability, and work of fracture, are also of crucial importance for the applications of the scaffolds in load-bearing defects.

3.1 Strength

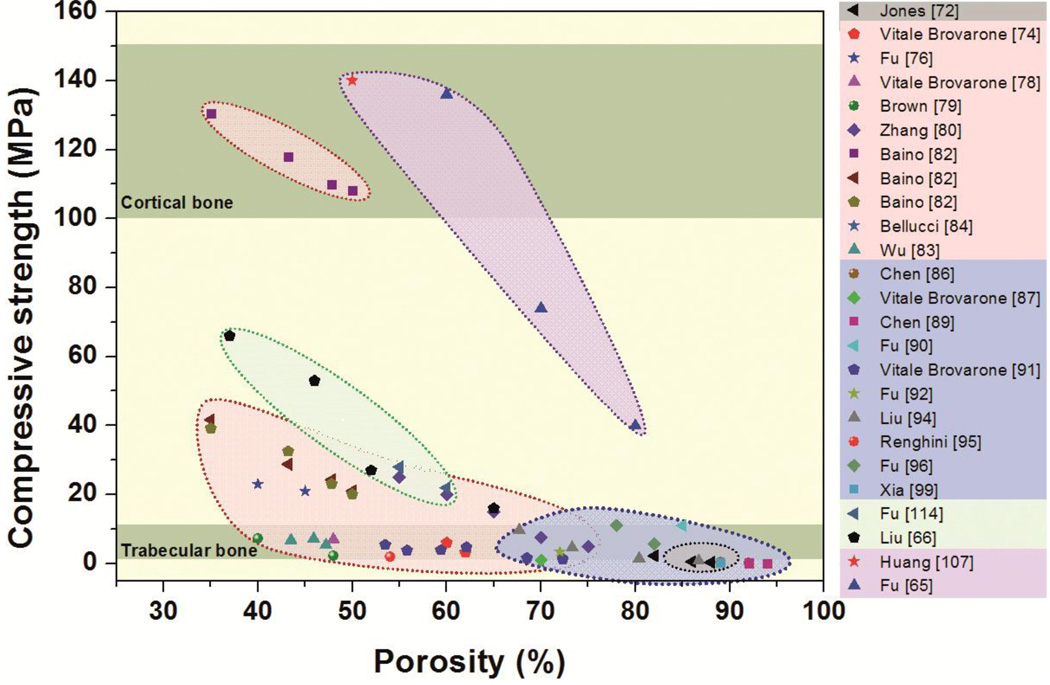

Data compiled from over 20 studies (Fig. 4) show the range of compressive strengths for bioactive glass scaffolds with different compositions and fabricated using a variety of methods. Table 2 provides details of the composition and pore characteristics of the scaffolds. A few trends can be observed. First, the compressive strengths span almost three orders of magnitude, ranging from 0.2 to 150 MPa for porosities of 30–95%. For the same glass composition and scaffold microstructure (fabrication method), the strength increases with a decrease in porosity, which is also commonly observed for other porous materials. The data show that porous bioactive glass scaffolds can be fabricated with compressive strengths comparable to the values reported for human trabecular and cortical bones (Table 1). This observation may be surprising to many researchers who often assume that bioactive glass scaffolds suffer from low strength and are therefore not suitable for the repair of load-bearing bone defects.

Figure 4.

Compressive strength of bioactive glass scaffolds complied from over 20 different studies, and grouped by fabrication methods. Gray: sol-gel, pink: thermally bonding of particles, blue: polymer foam replication, green: freeze casting and purple: solid freeform fabrication.

Table 2.

Compositions and pore characteristics of bioactive glass scaffolds (Legend to Fig. 4)

| Methold | Symbol | Reference | Glass system | Pore size (µm) | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sol-gel | Jones [72] | 70S30C: SiO2-CaO | 100–500 | 82–88 | |

| Thermally bonding of particles, fibers or spheres |

Vitale Brovarone [74] | SCK: SiO2-CaO-K2O | 100–150 | 60–62 | |

| Fu[76] | 13–93: SiO2-Na2O-K2O-MgO-CaO-P2O5 | 100–300 | 40–45 | ||

| Vitale Brovarone [78] | CEL2: SiO2-P2O5-CaO-MgO-K2O-Na2O | 100–800 | 48 | ||

| Brown [79] | 13–93 | 50–500 | 40–48 | ||

| Zhang [80] | A-W: CaO-MgO-SiO2-P2O5-CaF2 | 250–350 | 55–75 | ||

|

|

|||||

|

|

Baino [82] | Fa-GC: SiO2-CaO-Na2O-K2O-P2O5-MgO-CaF2 | 100–300 | 24–50 | |

|

|

|||||

| Bellucci [84] | Biok: SiO2-CaO-K2O-P2O5 | 100–500 | 70–80 | ||

| Wu [83] | 45S5: Na2O-CaO- SiO2-P2O5 | 100–420 | 44–48 | ||

| Polymer foam replication |

Chen [86] | 45S5 | 510–720 | 89–92 | |

| Vitale Brovarone [87] | CEL2 | 100–500 | 70 | ||

| Chen [89] | 45S5 | 510–720 | 92–94 | ||

| Fu [90] | 13–93 | 100–500 | 85 | ||

| Vitale Brovarone [91] | CEL2 | 100–500 | 54–73 | ||

| Fu [92] | 13–93 | 250–500 | 72 | ||

| Liu [94] | D-AlK-B: Na2O-K2O-MgO-CaO-SiO2-P2O5-B2O3 | 100–500 | 68–87 | ||

| Renghini [95] | CEL2 | 100–500 | 54 | ||

| Fu [96] | 13–93 | 100–500 | 78–82 | ||

| Xia [99] | 58S: CaO-SiO2-P2O5 | 100–500 | 89 | ||

| Freeze casting | Fu [114] | 13–93 | 90–110 | 55–60 | |

| Liu [66] | 13–93 | 10–160 | 19–60 | ||

| Solid freeform fabrication |

Huang [107] | 13–93 | 100–500 | 50 | |

| Fu [65] | 6P53B: Na2O-K2O-MgO-CaO-SiO2-P2O5 | 500–1000 | 60–80 | ||

Three studies by the same research group.

Second, the data show that the architecture (or microstructure) of the scaffold, which results from the fabrication method, has a strong effect on the strength, regardless of the composition of the glass. For the same porosity, scaffolds with an oriented pore architecture show far higher compressive strength (along the pore orientation direction) than scaffolds with a random or isotropic pore architecture. Among the common fabrication methods, unidirectional freezing of suspensions and solid freeform fabrication provide greater ease for the production of glass scaffolds with oriented pores. For example, Liu et al [66] created 13–93 bioactive glass scaffolds by unidirectional freezing of camphene-based suspensions, followed by thermal annealing to increase the pore diameter. They found that the compressive strength along the pore orientation direction was 2–3 times the value in the direction perpendicular to the pore orientation direction. In another study in which robocasting was used to fabricate 6P53B bioactive glass scaffolds, Fu et al [65] reported a compressive strength along the pore orientation direction which was 2.5 times the value in the perpendicular direction. The strength of these scaffolds in the orientation direction (136 MPa) is in the range reported for human cortical bone. These “oriented” bioactive glass scaffolds are likely to provide the requisite strength for the repair of load bearing applications.

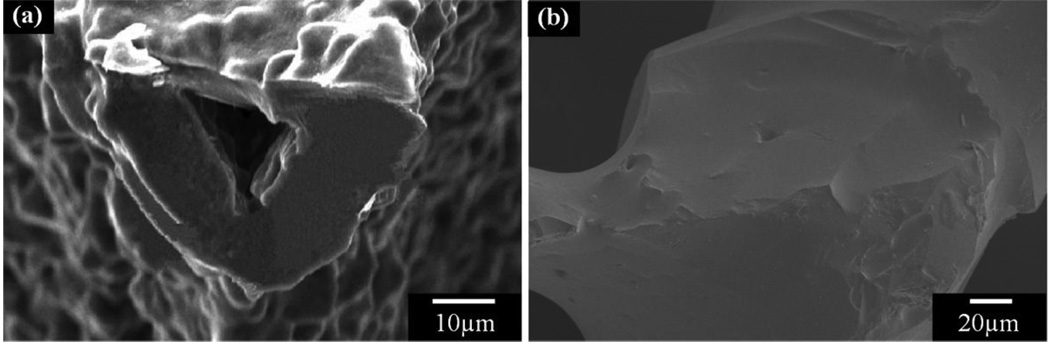

The strength-porosity data in Figure 4 show that for a given architecture (fabrication method), the glass composition can also have a marked effect on the mechanical strength of the scaffold. As an example, for scaffolds with approximately the same porosity (>80%) which were prepared by a polymer foam replication technique, the strength of 13–93 bioactive glass scaffolds (11 MPa) was almost 20 times the value for 45S5-derived glass-ceramic scaffolds (0.5 MPa). This difference in strength resulted primarily from the difference in sintering characteristics of the two glasses. 45S5 glass is prone to crystallization (devitrification) at sintering temperatures above ~1000°C, which leads to the formation of a predominantly combeite crystalline phase. This crystallization reduces the tendency of 45S5 glass to densify by viscous flow sintering. As a result, voids remaining from the burnout of the polymer foam are difficult to fill and may remain as triangular-shaped pores in the struts (Fig. 5a); these pores within the glass struts lead to a reduction in the strength of the scaffold. In comparison, as the sintering temperature of 13–93 glass is below its crystallization temperature, viscous flow sintering can lead to complete filling of the voids in the glass struts (Fig. 5b), leading to an improvement in the strength of the scaffold.

Figure 5.

Effects of glass composition on the microstructure of glass scaffolds: (a) 45S5-derived glass-ceramic scaffolds with a triangle hole within the rod; (b) 13–93 glass scaffolds with densified rods

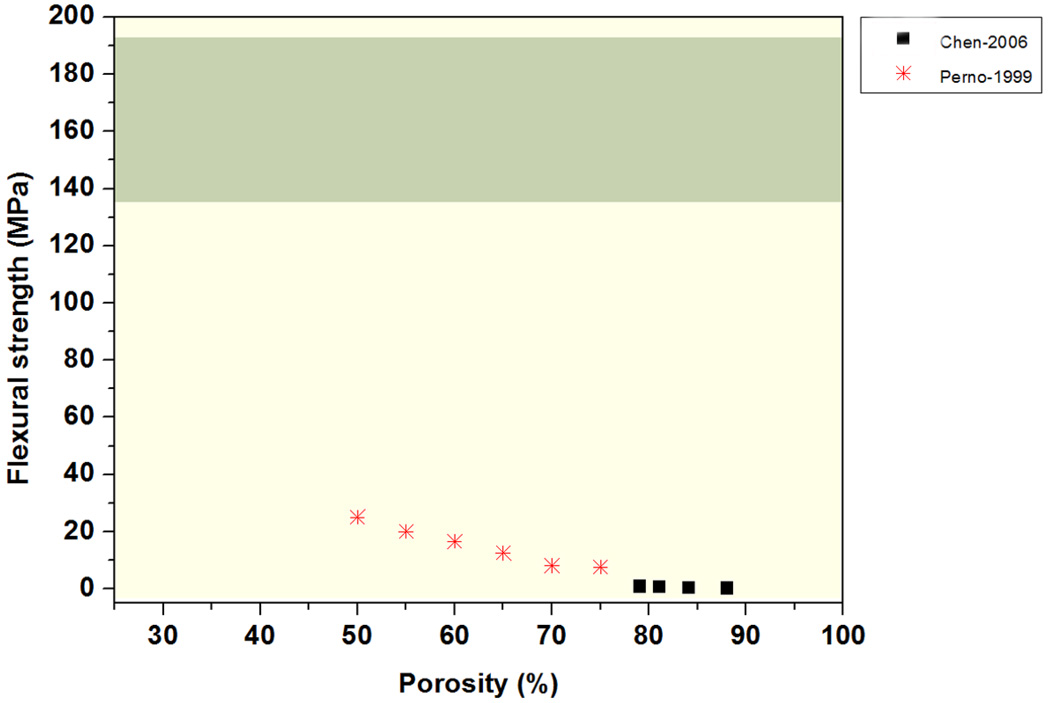

The flexural strength of two groups of bioactive glass scaffolds prepared using a polymer foam replication technique has been reported to span almost two orders of magnitude, in the range 0.4 to 25 MPa for porosities of 50–88% (Figure 6) [118, 119]. These flexural strengths are far lower than those reported for cortical bone (Table 1), but the value is comparable to that of human trabecular bone (10 – 20 MPa). As previously discussed, when compared to scaffolds prepared by the polymer foam replication technique, bioactive glass scaffolds prepared by unidirectional freezing of suspensions and solid freeform fabrication commonly have far higher compressive strengths. The mechanical response of these scaffolds in flexural loading is currently being evaluated in our lab.

Figure 6.

Flexural strength of bioactive glass scaffolds complied from 2 different studies.

To summarize, recent studies show that strength is not a limiting factor in the use of bioactive glass scaffolds for the repair of load-bearing defects. Optimization of the glass composition, coupled with improved control of the pore architecture using methods such as unidirectional freezing of suspensions and solid freeform fabrication, has resulted in the creation of scaffolds with the requisite combination of strength and porosity.

3.2 Fracture toughness and reliability

Scaffolds implanted in load-bearing bone defects are usually subjected to cyclic loading; therefore in addition to strength and elastic modulus, other mechanical properties such as fracture toughness and reliability are also of crucial importance. As described above, bioactive glass scaffolds can be created with the desired compressive strength for the repair of load-bearing bone defects (Fig. 4). However, their use in these applications may be limited by their intrinsic brittleness or low resistance to crack propagation. Commonly, the resistance of a material to crack propagation is measured in terms of an engineering parameter called the fracture toughness, denoted K1c. The K1c values for ceramics and glass are inherently low (typically K1c = 0.5–5 MPa·m1/2 for ceramics and 0.5–1 MPa·m1/2 for glass). Because of their low fracture toughness, ceramics and glass are very sensitive to the presence of small defects and flaws (~ 10 µm) and they can fail catastrophically when subjected to tensile or flexural stresses far lower than their compressive strength [120, 121]. While the fracture of brittle ceramics has been widely studied [47, 122, 123], there has been little effort to apply this knowledge to quantifying “brittle behavior” or toughness of porous bioactive glass scaffolds. Brittle behavior is often quantified using one or more of the following parameters: fracture toughness, Weibull modulus, and work of fracture.

Standard test methods for measuring the fracture toughness of brittle materials are specified by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) [124]. Typically, specimens in the shape of a beam (3 × 4 mm in cross section × 20–50 mm long), containing a sharp notch or a crack produced as a result of loading, are loaded in three-point or four-point flexure. In three-point flexure, K1c is determined by the following equation:

| (1) |

where a is the crack (or notch) length, W is the top to bottom dimension of the test specimen parallel to the crack length (depth), g is the function of the ratio a/W for three-point flexure, Pmax is the maximum force applied, S0 is the outer span is the specimens, B is the side to side dimension of the test specimen perpendicular to the crack length. The corresponding equation for four-point flexural loading is:

| (2) |

where f is the function of the ratio a/W for three-point flexure and S1 is the inner span.

The low strength of some bioactive glass scaffolds often provides difficulties in machining of the porous specimens into standard test bars with specific size and geometry. However, as previously discussed, strong and porous bioactive glass scaffolds can be created using solid freeform fabrication and unidirectional freezing of suspensions [65, 66], alleviating the machining difficulties associated with weak scaffolds.

Studies on the fracture behavior and reliability of porous scaffolds prepared from a CaO–Al2O3–P2O5 glass were characterized by measuring the fracture toughness of specimens with different porosities in three-point bending at room temperature [119]. The beam-shaped specimens, cut from porous scaffolds, were 20 mm long, and contained a notch (≤ 70 µm thick) of depth = 1.3 mm which was machined at the midpoint of one face. The K1c values were in the range 0.2–0.6 MPa•m1/2 for samples with porosities of 50–75%, far lower than the values reported for cortical bone (2–12 MPa•m1/2).

The reliability or the probability of failure of brittle materials is commonly quantified by a probability function proposed by Weibull [125], which is applicable to failure occurring from critical flaws. The Weibull distribution is given as a cumulative distribution:

| (3) |

where Pf(σ) is the probability of failure at a stress σ, σ0 is a scaling constant, σt is the threshold stress below which no failure occurs in the material, that practically can be taken as zero for brittle ceramics, and m is the Weibull modulus. The Weibull modulus, m, determines the reliability of the materials, with larger values corresponding to more reliable materials. To evaluate Pf the following equation is used:

| (4) |

where N is the total number of specimens tested and n is the specimen rank in ascending order of failure stress. To get an unbiased estimate of the failure probability, the recommended number of specimens is between 20 and 30 [126, 127].

The Weibull distribution has been used to evaluate the reliability of porous ceramic scaffolds [104, 128, 129], but the evaluation of porous bioactive glass scaffolds has received little attention. In one study, the Weibull distribution was used to evaluate the reliability of porous bioactive glass scaffolds (a CaO–Al2O3–P2O5 glass composition) in four-point flexural loading[119]. The measured Weibull modulus, in the range 3–8, was comparable to the values (3–9) reported for porous calcium phosphate scaffolds [104, 128, 129]. While the Weibull modulus provides a useful parameter for evaluating the reliability of the porous scaffolds, the requirement of a large number of test specimens may not be practical for some studies.

A simple way to measure the fracture toughness of porous scaffolds may be the work of fracture, γwof, i.e. the total energy consumed to produce a unit area of fracture surface during complete fracture [130]. Several groups have used the work of fracture to evaluate the toughness of porous glass and ceramic scaffolds [118, 131–133]. However, the work of fracture can only be used for comparison within a given study because it is not a true material property and it may vary due to the differences in sample dimension, sample geometry, and testing conditions.

While the compressive strength and elastic modulus of bioactive glass scaffolds have been widely studied, the brittle behavior and reliability of these scaffolds have received little attention. There is a need for more studies in this area because bioactive glass scaffolds are being considered for the repair of defects in loaded bone.

3.3 Toughening of porous bioactive glass scaffolds

Cortical bone has a fracture toughness of 2–12 MPa·m1/2 (Table 1), far higher than the values for the glass. Bone is a composite material, composed of collagen (35 dry wt%) for flexibility and toughness, carbonated apatite (65 dry wt%) for structural reinforcement, stiffness and mineral homeostasis, and other non-collagenous proteins for support of cellular functions (Fig. 1) [31] [134]. The toughening mechanisms in bone are reported to be crack deflection, microcracking, uncracked ligament bridging and collagen bridging of these, crack bridging by collagen fibrils has been reported to play an important role in toughening bone [135].

Inspired by the toughening mechanisms in bone, studies have been carried out to improve the toughness of porous glass and ceramic scaffolds. One approach is to coat or infiltrate the scaffold with a biodegradable polymer, providing an organic phase to toughen the inorganic phase. By coating alumina scaffolds with Polycaprolactone, PCL, a 7–13-fold increase in the work of fracture has been reported [131, 132]. In another study, they found that the work of fracture of biphasic calcium phosphate scaffolds increased up to 10 times after coating with the polymer. The significant increase in the toughness of these scaffolds is mainly attributed to the crack bridging by PCL fibrils.

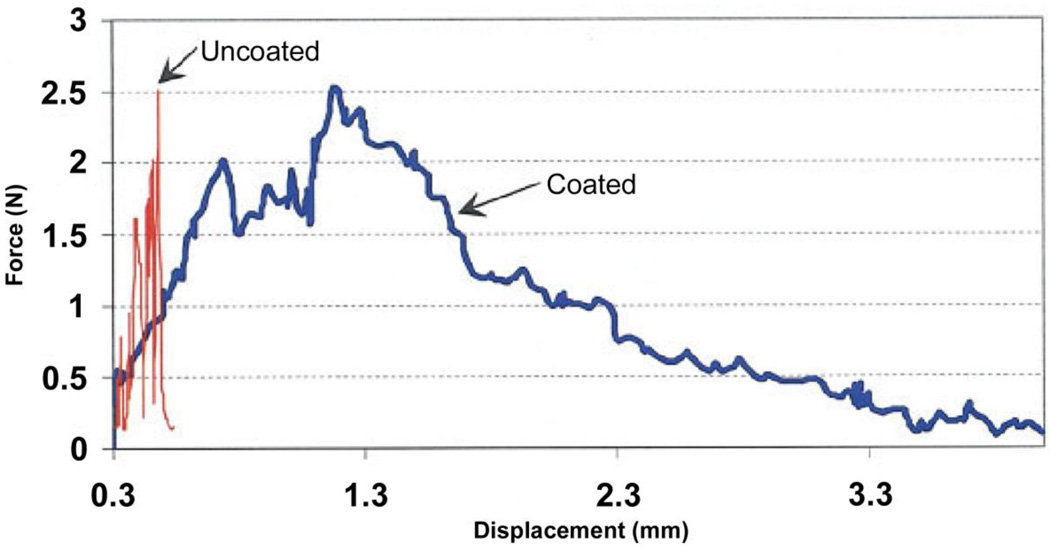

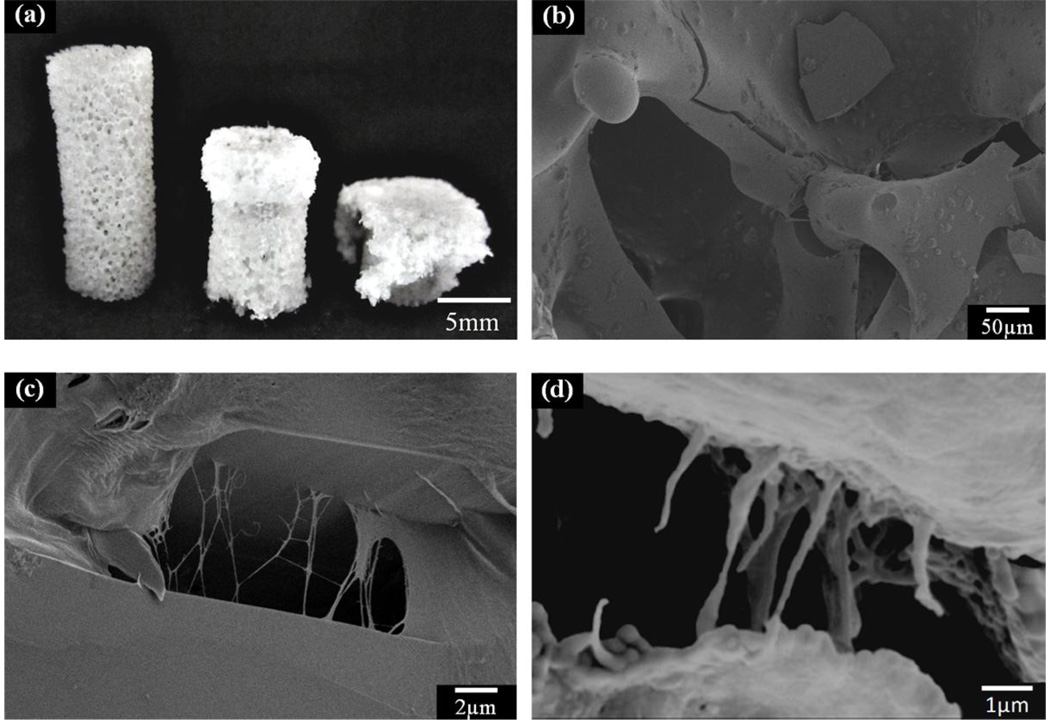

This approach of using a polymer coating has also been applied to the toughening of bioactive glass scaffolds. Biodegradable polymers, such as poly(D,L-lactic acid), PDLLA, poly(3-hydroxybutyrate), P(3HB), alginate, and PCL, have been used to coat bioactive glass scaffolds [118, 133, 136–138]. Chen et al. studied the effects of PDLLA coating on the mechanical properties of 45S5 bioactive glass-based scaffolds, and used the work of fracture in three-point bending to quantify the brittle behavior of the scaffolds. The work of fracture of scaffold coated with PDLLA was found to be 20 times higher than that for the scaffold without the polymer coating (Fig. 7). A similar study it was reported showed that coating scaffolds of the same glass with P(3HB) resulted in a doubling of the work of fracture [133]. Fu et al. [138] studied the effect of a PCL coating on the mechanical response of 13–93 bioactive glass scaffolds prepared by polymer foam replication method. The typical “brittle” behavior and catastrophic failure of the uncoated scaffolds was not observed upon compression the PCL-coated glass scaffold. Instead, the PCL-coated scaffolds showed a “plastic” response with a gradual failure mode (Fig. 8a). The main energy dissipation mechanism was believed to be PCL fibril extension and crack bridging, as observed from SEM images of the fractured scaffold (Figs. 8b, 8c). These toughening mechanism appear to be similar in nature to those provided by collagen fibrils in cortical bone (Fig. 8d).

Figure 7.

Stress-strain curve of toughened glass scaffolds (From Ref. 118)

Figure 8.

PCL toughened bioactive 13–93 glass scaffolds. (a) Optical image of the uncompressed (left) and compressed scaffolds (middle and right); (b) SEM image of the fracture surface of the scaffold; (c) high magnification of (b) to show the crack bridging by PCL fibrils; (d) crack bridging by collagen fibrils in human bone. (From Ref. 135)

While studies have been performed to evaluate the toughening of bioactive glass scaffolds, these studies have performed on scaffolds with a low strength. It is necessary to evaluate the toughening of bioactive scaffolds with far higher strength (e.g., compressive strength of 100–150 MPa, comparable to the values for cortical bone), for applications in the repair of load-bearing bone defects.

4. In vitro and in vivo response of bioactive glass scaffolds

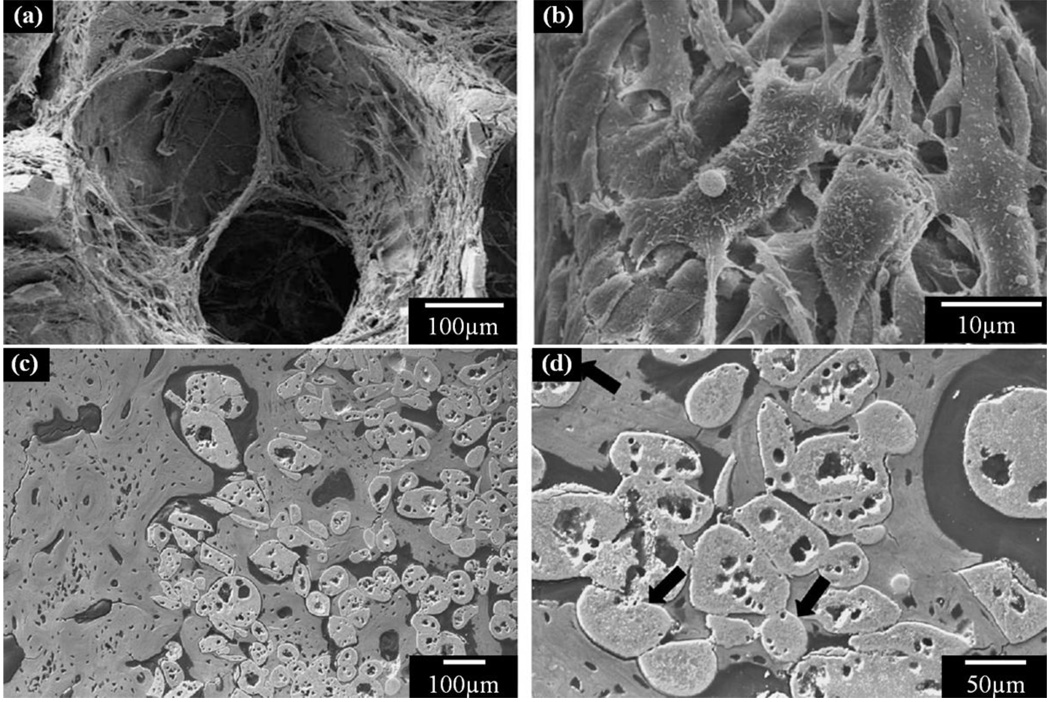

The in vitro and in vivo responses of bioactive glass scaffolds are dependent primarily on the glass composition and the pore architecture (microstructure) of the scaffolds. The ability of bioactive glass scaffolds to support cell proliferation and function in vitro and tissue ingrowth in vivo has been shown in numerous studies [90, 106, 139–142] [97, 115]. Fu et al. [90] showed that 13–93 bioactive glass scaffolds prepared using a polymer foam replication method supported the attachment and proliferation of MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblastic cells both on the surface and within the interior pores of the scaffold (Figs. 9a, 9b). Animal models including dogs, rabbits and rats have been used for the in vivo evaluation of bioactive glass scaffolds [97, 106, 115, 139–142]. In a rabbit tibia model, Goodridge et al. observed bone ingrowth into the pores of an apatite-mullite glass-ceramic scaffold prepared by selective laser sintering after implantation for 4 weeks [106]. Direct bonding between the scaffold and newly formed bone was observed (Figs. 9c, 9d). Further investigations are needed to evaluate the mechanical and chemical degradation of bioactive glass scaffolds and their integration with host bone when implanted in load-bearing defect sites in animal models.

Figure 9.

Cell and bone ingrowth in bioactive glass scaffolds. (a) Cell infiltration in bioactive 13–93 glass scaffolds; (b) Detailed cell morphology on the scaffold; (c) bone ingrowth in apatite-mullite scaffold; (d) High magnification of (c) to show the direct contact of bone to glass scaffold. (From Ref. 90 and 106).

5. Conclusions and Future trends

The fabrication, mechanical properties, and in vitro and in vivo performance of bioactive glass scaffolds were reviewed with emphasis on the mechanical behavior of the scaffolds for applications in the repair of loaded bone defects. Bioactive glass scaffolds with compressive strengths comparable to those of trabecular bone have been prepared using several methods; these scaffolds have potential for the repair of non-loaded bone defects. Recently, bioactive glass scaffolds with strengths comparable to those of cortical bone have been created, and these scaffolds may have potential for the repair of loaded bone defects. The toughness and mechanical reliability of bioactive glass scaffolds remain as limiting factors for applications in loaded bone repair, but so far they have received little attention. The addition of a biocompatible polymer coating is proposed as method for improving the toughness of bioactive glass scaffolds, providing a crack bridging mechanism by the polymer layer for energy dissipation. A focus of future work should be the creation of strong and tough bioactive glass scaffolds using advanced fabrication techniques and their evaluation in loaded and non-loaded bone defect sites in animal models.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIH/NIDCR) Grant No. 1R01DE015633.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Science. 1993;260:920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nerem RM. Ann Biomed Eng. 1991;19:529–545. doi: 10.1007/BF02367396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper ML, Hansbrough JF. Surgery. 1991;109:198–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansbrough JF, Morgan J, Greenleaf G, Parikh M, Nolte C, Wilkins L. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1994;15:346–353. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eaglstein WH, Falanga V. Clinical Therapeutics. 1997;19:894–905. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black AF, Berthod F, L’Heureux N, Germain L, Auger FA. Faseb Journal. 1998;12:1331–1340. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vacanti CA, Bonassar LJ, Vacanti MP, Shufflebarger J. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:1511–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105173442004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruyt MC, van Gaalen SM, Oner FC, Verbout A, de Bruijn JD, Dhert WJA. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1463–1473. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcacci M, Kon E, Moukhachev V, Lavroukov A, Kutepov S, Quarto R, Mastrogiacomo M, Cancedda R. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:947–955. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao Y, Vacanti JP, Paige KT, Upton J, Vacanti CA. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1997;100:297–302. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199708000-00001. discussion 303–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valonen PK, Moutos FT, Kusanagi A, Moretti MG, Diekman BO, Welter JF, Caplan AI, Guilak F, Freed LE. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2193–2200. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Praemer A, Furner S, Rice DP. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons., Musculoskeletal conditions in the United States. 2nd ed. Park Ridge, Ill: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane NE. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;194:S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannoudis PV, Dinopoulos H, Tsiridis E. Injury-International Journal of the Care of the Injured. 2005;36:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Long WG, Einhorn TA, Koval K, Mckee M, Smith W, Sanders R, Watson T. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume. 2007;89A:649–658. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UK Department of Health. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute of Dental Research Workshop. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piehler HR. Mrs Bull. 2000;25:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huiskes R, Weinans H, Vanrietbergen B. Clin Orthop Relat R. 1992:124–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webster TJ, Siegel RW, Bizios R. Nanostructured Materials. 1999;12:983–986. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutmacher DW. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2529–2543. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollister SJ, Maddox RD, Taboas JM. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4095–4103. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Ma PX. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:477–486. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000017544.36001.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salgado AJ, Coutinho OP, Reis RL. Macromolecular Bioscience. 2004;4:743–765. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200400026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sittinger M, Hutmacher DW, Risbud MV. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2004;15:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollister SJ. Nature Materials. 2005;4:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nmat1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen VJ, Smith LA, Ma PX. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3973–3979. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karageorgiou V, Kaplan D. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5474–5491. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagoner Johnson AJ, Herschler BA. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7:16–30. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fratzl P, Gupta HS, Paschalis EP, Roschger P. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:2115–2123. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reilly DT, Burstein AH, Frankel VH. J Biomech. 1974;7 doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(74)90018-9. 271-&. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein SA. J Biomech. 1987;20:1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rohl L, Larsen E, Linde F, Odgaard A, Jorgensen J. J Biomech. 1991;24:1143–1149. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keaveny TM HW. Mechanical Properties of Cortical and Trabecular Bone. In: Hall BK, editor. Bone. Boca Raton, FL: A Treatise, CRC Press; 1993. pp. 285–344. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fung YC. Biomechanics: mechanical properties of living tissues. 2nd ed. New York ; London: Springer-Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rho JY, Hobatho MC, Ashman RB. Med Eng Phys. 1995;17:347–355. doi: 10.1016/1350-4533(95)97314-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin RB, Burr DB, Sharkey NA. Skeletal tissue mechanics. New York ; London: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zioupos P, Currey JD. Bone. 1998;22:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oyen ML. Mrs Bull. 2008;33:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wegst UGK, Ashby MF. Philosophical Magazine. 2004;84:2167–2181. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayashi T. Progress in Polymer Science. 1994;19:663–702. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agrawal CM, Ray RB. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2001;55:141–150. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200105)55:2<141::aid-jbm1000>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffith LG. Acta Mater. 2000;48:263–277. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee KY, Mooney DJ. Chemical Reviews. 2001;101:1869–1879. doi: 10.1021/cr000108x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varghese S, Elisseeff JH. Polymers for Regenerative Medicine. 2006:95–144. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reis RL. Natural-based polymers for biomedical applications. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing Limited; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomson RC, Yaszemski MJ, Powers JM, Mikos AG. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1935–1943. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rezwan K, Chen QZ, Blaker JJ, Boccaccini AR. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3413–3431. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Groot K. Ceram Int. 1993;19:363–366. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daculsi G, Laboux O, Malard O, Weiss P. J Mater Sci-Mater M. 2003;14:195–200. doi: 10.1023/a:1022842404495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dorozhkin SV. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1465–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levengood SKL, Polak SJ, Poellmann MJ, Hoelzle DJ, Maki AJ, Clark SG, Wheeler MB, Johnson AJW. Acta Biomaterialia. 2010;6:3283–3291. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hench LL, Splinter WC, Allen WC, Greenlee TK. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Symp. 1971;2:117–141. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hench LL. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 1998;81:1705–1728. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rahaman MN, Brown RF, Bal BS, Day DE. Semi Arthrop. 2006;17:102–112. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yunos DM, Bretcanu O, Boccaccini AR. J Mater Sci. 2008;43:4433–4442. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wheeler DL, Stokes KE, Park HM, Hollinger JO. Journal of biomedical materials research. 1997;35:249–254. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199705)35:2<249::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wheeler DL, Stokes KE, Hoellrich RG, Chamberland DL, McLoughlin SW. Journal of biomedical materials research. 1998;41:527–533. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980915)41:4<527::aid-jbm3>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xynos ID, Edgar AJ, Buttery LDK, Hench LL, Polak JM. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;276:461–465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xynos ID, Edgar AJ, Buttery LDK, Hench LL, Polak JM. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2001;55:151–157. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200105)55:2<151::aid-jbm1001>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leach JK, Kaigler D, Wang Z, Krebsbach PH, Mooney DJ. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3249–3255. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leu A, Leach JK. Pharmaceutical Research. 2008;25:1222–1229. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gorustovich AA, Roether JA, Boccaccini AR. Tissue Engineering Part B-Reviews. 2010;16:199–207. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2009.0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fu Q, Saiz E, Tomsia AP. Adv Funct Mater. 2011;21:1058–1063. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu X, Rahaman MN, Fu QA. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7:406–416. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hulbert SF, Young FA, Mathews RS, Klawitter JJ, Talbert CD, Stelling FH. J Biomed Mater Res. 1970;4:433–456. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820040309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hollinger JO, Brekke J, Gruskin E, Lee D. Clin Orthop Relat R. 1996:55–65. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199603000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jones JR, Hench LL. J Mater Sci. 2003;38:3783–3790. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jones JR, Ahir S, Hench LL. J Sol-Gel Sci Techn. 2004;29:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gough JE, Jones JR, Hench LL. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2039–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jones JR, Ehrenfried LM, Hench LL. Biomaterials. 2006;27:964–973. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rainer A, Giannitelli SM, Abbruzzese F, Traversa E, Licoccia S, Trombetta M. Acta Biomaterialia. 2008;4:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vitale-Brovarone C, Di Nunzio S, Bretcanu O, Verne E. J Mater Sci-Mater M. 2004;15:209–217. doi: 10.1023/b:jmsm.0000015480.49061.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brovarone CV, Verne E, Appendino P. J Mater Sci-Mater M. 2006;17:1069–1078. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fu Q, Rahaman MN, Bal BS, Huang W, Day DE. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82A:222–229. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liang W, Rahaman MN, Day DE, Marion NW, Riley GC, Mao JJ. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 2008;354:1690–1696. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vitale-Brovarone C, Verne E, Robiglio L, Martinasso G, Canuto RA, Muzio G. J Mater Sci-Mater M. 2008;19:471–478. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brown RF, Day DE, Day TE, Jung S, Rahaman MN, Fu Q. Acta Biomaterialia. 2008;4:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang H, Ye XJ, Li JS. Biomed Mater. 2009;4 doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/4/4/045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haimi S, Gorianc G, Moimas L, Lindroos B, Huhtala H, Raty S, Kuokkanen H, Sandor GK, Schmid C, Miettinen S, Suuronen R. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5:3122–3131. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baino F, Verne E, Vitale-Brovarone C. Materials Science & Engineering C-Materials for Biological Applications. 2009;29:2055–2062. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu SC, Hsu HC, Hsiao SH, Ho WF. J Mater Sci-Mater M. 2009;20:1229–1236. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3690-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bellucci D, Cannillo V, Ciardelli G, Gentile P, Sola A. Ceram Int. 2010;36:2449–2453. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schwarzwalder K, Somers AV. USA. 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen QZZ, Thompson ID, Boccaccini AR. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2414–2425. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vitale-Brovarone C, Verne E, Robiglio L, Appendino P, Bassi F, Martinasso G, Muzio G, Canuto R. Acta Biomaterialia. 2007;3:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li Y, Rahaman MN, Fu Q, Bal BS, Yao A, Day DE. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2007;90:3804–3810. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen QZ, Efthymiou A, Salih V, Boccaccinil AR. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;84A:1049–1060. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fu Q, Rahaman MN, Bal BS, Brown RF, Day DE. Acta Biomaterialia. 2008;4:1854–1864. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vitale-Brovarone C, Baino F, Verne E. J Mater Sci-Mater M. 2009;20:643–653. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fu HL, Fu Q, Zhou N, Huang WH, Rahaman MN, Wang DP, Liu X. Materials Science & Engineering C-Materials for Biological Applications. 2009;29:2275–2281. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu X, Huang W, Fu H, Yao A, Wang D, Pan H, Lu WW. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2009;20:365–372. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3582-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu X, Huang W, Fu H, Yao A, Wang D, Pan H, Lu WW, Jiang X, Zhang X. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2009;20:1237–1243. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Renghini C, Komlev V, Fiori F, Verne E, Baino F, Vitale-Brovarone C. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5:1328–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fu QA, Rahaman MN, Fu HL, Liu X. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;95A:164–171. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fu QA, Rahaman MN, Bal BS, Bonewald LF, Kuroki K, Brown RF. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010:172–179. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu X, Pan HB, Fu HL, Fu Q, Rahaman MN, Huang WH. Biomed Mater. 2010;5 doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/5/1/015005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xia W, Chang J. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2010;95:449–455. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chu T-MG. Solid Freeform Fabrication of Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. In: Ma X, Eliseeff J, editors. Scaffolding in Tissue Engineering. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 2005. pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sachlos E, Czernuszka JT. European Cells and Materials. 2003;3:29–40. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v005a03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miranda P, Saiz E, Gryn K, Tomsia AP. Acta Biomaterialia. 2006;2:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Russias J, Saiz E, Deville S, Gryn K, Liu G, Nalla RK, Tomsia AP. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;83A:434–445. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Miranda P, Pajares A, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Guiberteau F. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;85A:218–227. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Franco J, Hunger P, Launey ME, Tomsia AP, Saiz E. Acta Biomaterialia. 2010;6:218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Goodridge RD, Wood DJ, Ohtsuki C, Dalgarno KW. Acta Biomaterialia. 2007;3:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Huang TS, Rahaman MN, Doiphode ND, Leu MC, Bal BS, Day DE. Materials Science and Engineering:C (submitted) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schoof H, Apel J, Heschel I, Rau G. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;58:352–357. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang HF, Hussain I, Brust M, Butler MF, Rannard SP, Cooper AI. Nature Materials. 2005;4:787–793. doi: 10.1038/nmat1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Deville S, Saiz E, Nalla RK, Tomsia AP. Science. 2006;311:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.1120937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Song JH, Koh YH, Kim HE, Li LH, Bahn HJ. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2006;89:2649–2653. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fu Q, Rahaman MN, Dogan F, Bal BS. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B-Applied Biomaterials. 2008;86B:125–135. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fu Q, Rahaman MN, Dogan F, Bal BS. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B-Applied Biomaterials. 2008;86B:514–522. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Fu Q, Rahaman MN, Bal BS, Brown RF. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;93A:1380–1390. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fu QA, Rahaman MN, Bal BS, Kuroki K, Brown RF. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;95A:235–244. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wegst UGK, Schecter M, Donius AE, Hunger PM. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society a-Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2010;368:2099–2121. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Deville S, Saiz E, Tomsia AP. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5480–5489. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chen QZ, Boccaccini AR. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77A:445–457. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pernot F, Etienne P, Boschet F, Datas L. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 1999;82:641–648. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Davidge RW. Mechanical behaviour of ceramics. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sakai M, Bradt RC. International Materials Reviews. 1993;38:53–78. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Brezny R, Green DJ. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 1989;72:1145–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gibson LJ, Ashby MF. Cellular solids : structure and properties. 2nd ed. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 124.A. International. Pennsylvania, USA: West Conshohocken; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Weibull W. Journal of Applied Mechanics-Transactions of the Asme. 1951;18:293–297. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bergman B. Journal of Materials Science Letters. 1984;3:689–692. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sullivan JD, Lauzon PH. Journal of Materials Science Letters. 1986;5:1245–1247. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cordell JM, Vogl ML, Wagoner Johnson AJ. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2009;2:560–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Martinez-Vazquez FJ, Perera FH, Miranda P, Pajares A, Guiberteau F. Acta Biomaterialia. 2010;6:4361–4368. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Barinov SM, Sakai M. Journal of Materials Research. 1994;9:1412–1425. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Peroglio M, Gremillard L, Gauthier C, Chazeau L, Verrier S, Alini M, Chevalier J. Acta Biomaterialia. 2010;6:4369–4379. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Peroglio M, Gremillard L, Chevalier J, Chazeau L, Gauthier C, Hamaide T. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2007;27:2679–2685. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bretcanu O, Misra S, Roy I, Renghini C, Fiori F, Boccaccini AR, Salih V. J Tissue Eng Regen M. 2009;3:139–148. doi: 10.1002/term.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Athanasiou KA, Zhu CF, Lanctot DR, Agrawal CM, Wang X. Tissue Eng. 2000;6:361–381. doi: 10.1089/107632700418083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Nalla RK, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Nature Materials. 2003;2:164–168. doi: 10.1038/nmat832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mantsos T, Chatzistavrou X, Roether JA, Hupa L, Arstila H, Boccaccini AR. Biomed Mater. 2009;4 doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/4/5/055002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mourino V, Newby P, Boccaccini AR. Adv Eng Mater. 2010;12:B283–B291. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Fu Q, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Rahaman MN. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.016. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Itala A, Koort J, Ylanen HO, Hupa M, Aro HT. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;67A:496–503. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lee JH, Lee CK, Chang BS, Ryu HS, Seo JH, Hong S, Kim H. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77A:362–369. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Yuan HP, de Bruijn JD, Zhang XD, van Blitterswijk CA, de Groot K. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2001;58:270–276. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(2001)58:3<270::aid-jbm1016>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Zhao DS, Moritz N, Vedel E, Hupa L, Aro HT. Acta Biomaterialia. 2008;4:1118–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]