Abstract

This study examined family and neighborhood influences relevant to low-income status to determine how they combine to predict the parenting behaviors of Mexican–American mothers and fathers. The study also examined the role of parenting as a mediator of these contextual influences on adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Study hypotheses were examined in a diverse sample of Mexican–American families in which 750 mothers and 467 fathers reported on their own levels of parental warmth and harsh parenting. Family economic hardship, neighborhood familism values, and neighborhood risk indicators were all uniquely associated with maternal and paternal warmth, and maternal warmth mediated the effects of these contextual influences on adolescent externalizing symptoms in prospective analyses. Parents’ subjective perceptions of neighborhood danger interacted with objective indicators of neighborhood disadvantage to influence maternal and paternal warmth. Neighborhood familism values had unique direct effects on adolescent externalizing symptoms in prospective analyses, after accounting for all other context and parenting effects.

Keywords: Economic hardship, Neighborhood, Parenting, Culture, Adolescence, Mental health

Introduction

Mexican–Americans are a large and growing population that demonstrates abnormally high rates of mental health problems during adolescence (CDC 2006; Delva et al. 2005). These disparities are often attributed to their disproportionate exposure to contextual risk factors, particularly family and neighborhood economic disadvantage. However, despite their high concentration in disadvantaged neighborhoods and poverty rates nearly triple that of non-Latinos (National Center for Children in Poverty 2000), few studies have examined processes by which these contextual factors lead, over time, to adverse adolescent outcomes for this population. A specific focus on Mexican–Americans is important because this group experiences unique economic and cultural conditions that shape their families and neighborhoods, and may alter their response to contextual risks in the U.S. (Gonzales et al. in press). The current study addressed this gap by testing a prospective meditational model in which mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behavior was hypothesized to account, in part, for the link between contextual risk and adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

This work was informed by a cultural-ecological perspective which recognizes the several layers of overlapping contextual influences that shape developmental processes and person-environment transactions over time (e.g., Bronfenbrenner 1979; Szapocznik and Coatsworth 1999). In this framework, developing youth are influenced by and need to adapt to multiple social contexts simultaneously, including their family, peer, neighborhood, and school contexts, as well as broader macrosystem influences. Ecological models also emphasize the interplay of influences across contexts, and the way in which the presence and impact of risk in one setting (e.g., family) may depend on the presence of risk in other settings (e.g., neighborhood, peer group). Because it is difficult to test complex ecological models representing all relevant contexts and their interactive effects simultaneously, we selectively target the interplay between parenting and neighborhood, focusing on neighborhood effects on parenting and their joint effects on adolescent mental health symptoms.

We also integrate a cultural perspective to understand how Mexican–American parenting is influenced by the broader community and cultural context. Culture has been defined as patterns of behavior and ways of thinking that people living in distinct social groups learn, create, and share (Triandis 1994). A cultural ecological framework emphasizes that culture is not only a function of a shared cultural identity (i.e., ethnic group membership), but also is determined by factors such as family socioeconomic status (SES), immigration status, and the types of communities in which individuals settle (Roosa et al. 2002). These multiple influences combine to account for the unique cultural experiences of youth and families, and we believe they must be included to understand factors that shape Mexican–American parenting practices and ultimately affect youth adaptation.

Economic Hardship and Disrupted Parenting

According to family stress theory (FST), economic pressures due to financial strain lead to disruptions in parents’ personal functioning and in their family relations and parenting practices, and in turn place children at risk for internalizing and externalizing problems (Conger and Elder 1994; Conger et al. 2000). Disruptions in parenting occur on a number of dimensions but in general the quality of parenting is expected to deteriorate, leading to decreased nurturance or warmth in parents’ behavior toward their children and increased harsh and ineffective discipline strategies. Although a number of longitudinal studies have supported FST and the role of disrupted parenting as a central mechanism (e.g., Conger et al. 1997, 2000; Cutrona et al. 2003), Latino youth have not been represented in these studies. Thus, this study was one of the first to prospectively test parenting as a pathway through which socioeconomic disadvantage leads to poor mental health for Mexican–American adolescents. A test of this pathway is critical to inform developmental theory and lend empirical support to the use of parenting interventions for this population.

Empirical validation is especially needed with Mexican–Americans because the link between socioeconomic indicators and mental health are not as consistently shown in research with this population (e.g., Alegria et al. 2007; Crouter et al. 2006). It is possible these inconsistencies occur because the bulk of research with Mexican–Americans: has typically sampled from the poorest neighborhoods, thereby restricting variability on socioeconomic indicators; failed to account for variability within the Mexican–American population on factors that are highly correlated, and confounded, with income (e.g., immigrant status); and has failed to consider the possibility that objective indicators of income poverty may not have similar meaning for this population, particularly those that have immigrated from Mexico. A weaker association between income and economic pressure has been reported for Mexican–American families, which is attributed to a non-U.S. frame of reference and the greater sharing of resources that is characteristic of collectivistic cultures (Parke et al. 2004). Mexican immigrants, although technically living in poverty, may be materially better off than they were before migration thus feeling little economic pressure despite their financial circumstances. Economic hardship and economic pressure, concepts introduced by FST, capture the subjective experience or “psychological meaning’ of living in poverty (Conger and Conger 2002) and may be better at differentiating families who have learned to manage well with few resources from those who cannot (Barrera et al. 2002). The current study was ideally suited to address the foregoing limitations because it sampled broadly across SES levels, neighborhood types, and generation status; controlled for parents’ nativity; and included a measure of economic hardship that combined indicators of financial strain and economic pressure that have been included in prior family stress research.

Neighborhood Disadvantage and Disrupted Parenting

Social disorganization theory argues that poverty-related threats to youth adaptation also occur within the community, at the neighborhood level (Sampson et al. 1997). Neighborhood disadvantage, commonly defined as concentrated poverty and characteristics associated with it (e.g., high levels of unemployment, high crime rates), reduces social organization, which in turn impedes residents’ abilities to effectively control and regulate conventional behaviors within a neighborhood. The negative impacts of neighborhood disorganization on adult residents’ behaviors are further expressed through family functioning and parenting behaviors (Furstenberg 1993). Consequently, adolescents living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to experience lower levels of parental warmth and higher levels of harsh parenting (Pinderhughes et al. 2001), and this may increase their risk for internalizing and externalizing problems. A number of studies have supported this hypothesis with general population (e.g., Xue et al. 2005), African American (Ceballo and McLoyd 2002), and mixed Latino samples (Eamon and Mulder 2005), even after controlling for family SES. Although research with Mexican–Americans confirms detrimental effects of neighborhood disadvantage on family functioning (Deng et al. 2006; Roosa et al. 2005), this research has not focused specifically on parenting.

In a recent exception, White et al. (2009) examined Mexican–American parents’ perceptions of economic hardship and neighborhood danger in a cross-sectional test of parent depression as a mediator of the link between context and parenting. They found economic hardship was positively related to depression for mothers and fathers, and had indirect effects on parental warmth that were mediated by parents’ depression. Perceptions of living in a dangerous neighborhood also predicted higher levels of depression for fathers, but not mothers. In addition to highlighting the importance of studying fathers (Cabrera and Garcia Coll 2004), particularly in Mexican–American families where two-parent families are more prevalent (Upchurch et al. 2001), these findings introduced evidence that mothers and fathers may respond in different ways to neighborhood conditions. The current study drew from the same sample as White et al. (2009) but tested direct effects of context on mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. This study extended this research further by examining prospective effects of contextual risk and parenting on internalizing and externalizing symptoms assessed 2 years later, when the youth were in 7th grade. Neighborhood effects are expected to increase as youth enter adolescence and have increased contact with peers and activities within their neighborhoods (Boyce et al. 1998). The study also included objective and subjective indicators of neighborhood context to explore whether predictions of parenting might be improved by considering both within the same model.

Although few studies have included both objective and subjective indicators, doing so may allow for a more nuanced understanding of parents’ reactions to neighborhood risk and the underlying processes by which neighborhood context impacts parenting. For example, research with African Americans has shown that when parents in disadvantaged neighborhoods are concerned about threatening neighborhood conditions and they perceive their neighborhoods to be dangerous, they may use more extreme measures, including harsh disciplinary strategies, to guard and protect youth (Mason et al. 1996). When employed strategically in response to a dangerous context, higher levels of harsh parenting also may be accompanied by high levels of warmth in the parent–child relationship (Deater-Deckard et al. 2006). Findings such as these offer a different interpretation of neighborhood effects on parenting by suggesting that they might not only result as “disruptions” in parenting brought on by increase stress and social disorganization, but may reflect conscious, strategic adaptations that parents make to cope with a threatening context. These findings also suggest that objective indicators of neighborhood disadvantage (e.g., census data, police crime data) may interact with parents’ perceptions and may show stronger or qualitatively different relations with parenting depending on parents’ subjective awareness or sensitivity to objective neighborhood dangers. This hypothesis was examined in the current study by testing interactive effects of objective neighborhood disadvantage, based on census block group data, with parents’ perceptions of neighborhood danger. We expected disadvantage neighborhoods would have stronger effects on parenting when parents perceived their neighborhoods as more dangerous.

Familism describes a strong identification and attachment of individuals with their immediate and extended families and strong feelings of loyalty, reciprocity and solidarity among family members, which often includes non-biological members of a supportive family network (Comas-Diaz 1989). Because of the centrality of familism in traditional Mexican culture (Marin and Marin 1991), ethnically identified Mexican–American communities often have a strong orientation to family and the importance of raising children that will stay on “el buen camino” (“the good path”; Azmitia and Brown 2002). Accordingly, these neighborhoods are oriented toward supporting parental authority and parents efforts to protect and guide youth. Although most studies of community focus only on risks, there is some evidence that community cultural orientation and values can protect Mexican–Americans from the negative effects of poverty (Huie et al. 2002; Denner et al. 2001). Thus, this study included a community-level measure of familism values as a potentially important dimension of neighborhood context that may impact parenting in Mexican–American families. We predicted neighborhoods characterized by high levels of familism would support parents to maintain warm, respectful relations with their children that are highly valued within traditional Mexican culture, thus providing some compensation for family and neighborhood disadvantage.

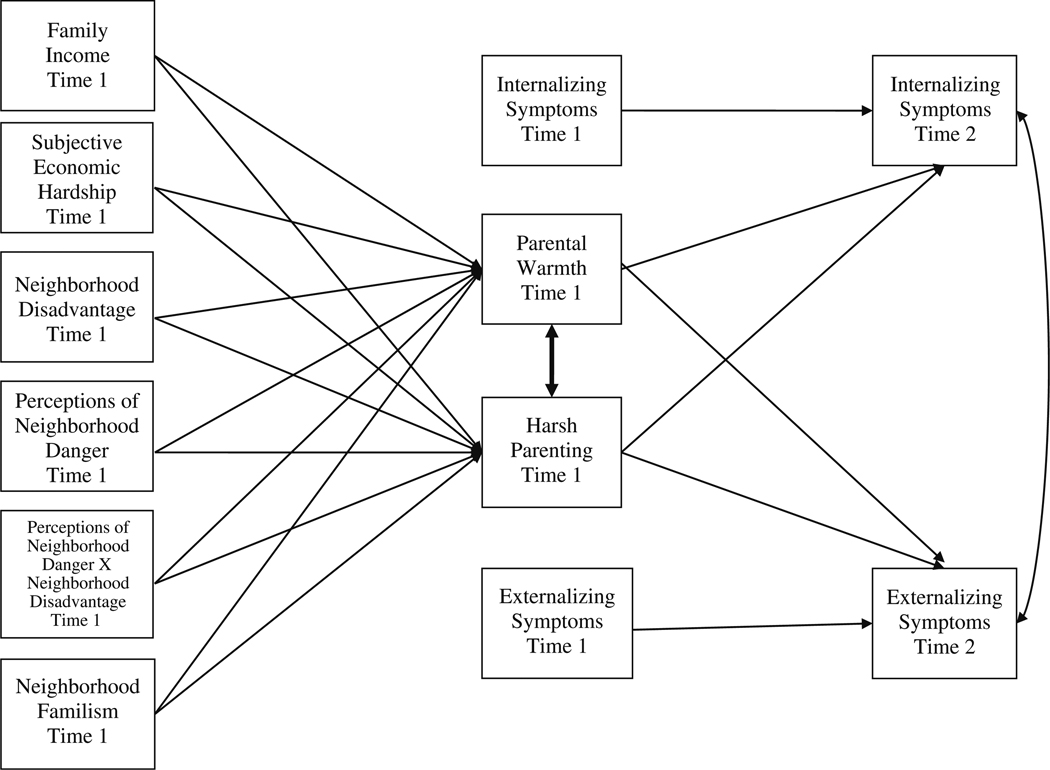

The full hypothesized model is presented in Fig. 1. Consistent with family stress and social disorganization theories, we hypothesized that objective and subjective indicators of family economic hardship and neighborhood disadvantage would be associated with disrupted parenting (low warmth, high levels of harsh parenting), but subjective indicators (i.e., parents’ perceptions of danger) would show stronger relations in the model. We also expected objective (i.e., census block group) indicators of neighborhood disadvantage would interact with parents’ perceptions of neighborhood danger and show stronger effects for parents who perceived neighborhoods as more dangerous. Neighborhood familism was expected to have compensatory protective benefits to predict less disrupted parenting. Disrupted parenting was expected, in turn, to predict increased internalizing and externalizing symptoms in 7th grade, controlling for initial levels of these variables.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized Prospective Model of Context and Parenting Effects on Adolescent Mental Health

Method

Data for this study come from the first and second waves of an ongoing longitudinal study investigating the role of culture and context in the lives of Mexican–American families in a large southwestern metropolitan area (Roosa et al. 2008). Participants were recruited when they were students in 5th grade, selected from school rosters that served ethnically diverse communities. Eligible families met the following criteria at Time 1: (a) they had a target fifth grader attending a sampled school; (b) the participating mother was the child’s biological mother, lived with the child, and self-identified as Mexican or Mexican–American; (c) the child’s biological father was of Mexican origin; (d) the target child was not learning disabled; and (e) no step-father or mother’s boyfriend was living with the child. In total 750 mothers and 5th graders were interviewed at Time 1. Although participation was optional for fathers, 467 (81.9%) fathers from the 570 two-parent families in the study also participated.

Data describing the full sample (mothers and children) and the subsample (fathers and children) at Time 1 are presented in Table 1. Among the full sample, 22.9% were single-parent families and 77.1% were two-parent families. In contrast to the majority of previous studies of Mexican–American families, this sample was diverse on both SES indicators and language (Roosa et al. 2008). Family incomes ranged from less than $5,000 to more than $95,000, with the average family reporting an income of $30,000–$35,000. In terms of language, 30.2% of mothers, 23.2% of fathers, and 82.5% of adolescents were interviewed in English. The mean age of mothers in the study was 35.9 (SD = 5.81) and mothers reported an average of 10.3 (SD = 3.67) years of education. The mean age of fathers was 38.1 (SD = 6.26) and fathers reported an average of 10.1 (SD = 3.94) years of education. The mean age of adolescents (48.7% female) was 10.42 (SD = .55). A majority of mothers and fathers were born in Mexico (74.3, 79.9% respectively), while a majority of adolescents were born in the U.S. (70.3%).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the sample of families

| Variable (n mother/n father) | Full sample of mothers and children | Father-participating subsample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Range | Mean | SD | % | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Age of parents (750/463) | 25–54 | 35.86 | 5.81 | 27–63 | 38.09 | 6.26 | ||

| Age of children (749/467) | 9–12 | 10.43 | 0.54 | 9–12 | 10.40 | 0.54 | ||

| Family incomea (733/467) | 1–20 | 6.73 | 4.40 | 1–20 | 7.73 | 4.61 | ||

| Parents’ years of education (749/465) | 1–19 | 10.34 | 3.67 | 1–20 | 10.09 | 3.94 | ||

| Two parent household (750/467) | 77.07 | 99.78 | ||||||

| Parents born in U.S. (750/467) | 25.73 | 19.91 | ||||||

| Children born in U.S. (750/467) | 70.27 | 66.59 | ||||||

| Parents interviewed in English (749/467) | 30.17 | 23.18 | ||||||

| Children interviewed in English (749/467) | 82.77 | 81.58 | ||||||

| Female children (750/467) | 48.70 | 48.39 | ||||||

| Subjective economic hardship (745/466) | 1.47–2.54 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 1.31–2.57 | 0.00 | 0.82 | ||

| Perceived neighborhood danger (748/465) | 1–5 | 2.52 | 1.03 | 1–5 | 2.42 | 0.94 | ||

| Parental warmth (749/466) | 2.5–5 | 4.44 | 0.50 | 2.38–5 | 4.21 | 0.54 | ||

| Harsh parenting (749/466) | 1–4.63 | 2.18 | 0.64 | 1–3.88 | 1.95 | 0.59 | ||

| Internalizing symptoms—time 1 (748/−)b | 0–62.5 | 16.13 | 9.11 | 0–62.5 | 15.85 | 9.08 | ||

| Externalizing symptoms—time 1(742/−)b | 0–28.5 | 5.15 | 4.76 | 0–23.5 | 4.76 | 4.45 | ||

| Internalizing symptoms—time 2 (687/−)b | 0–59.5 | 13.22 | 8.04 | 0–41.5 | 12.87 | 7.43 | ||

| Externalizing symptoms—time 2(685/−)b | 0–30 | 5.80 | 4.97 | 0–26 | 5.32 | 4.34 | ||

income reported in multiples of $5,000

Internalizing and externalizing based on combination of mother and child report

Families were re-interviewed at T2 approximately 2 years after Time 1 data collection; time between interviews ranged from 20 to 34 months (X = 23.32, SD = 1.32). A total of 711 families participated at T2, resulting in a 95% rate of retention. Families who participated in Time 2 interviews were compared to families who did not on several Time 1 demographic variables and no differences emerged on child characteristics (i.e., gender, age, generational status, language of interview), mother characteristics (i.e., marital status, age, generational status) or father characteristics (i.e., age, generational status).

Procedures

Using a combination of random and purposive sampling, the research team identified communities served by 47 public, religious, and charter schools from throughout the metropolitan area chosen to represent the economic, cultural, and social diversity of the city (see Roosa et al. 2009 for full description of sampling methods). These schools were chosen from 237 potential schools in the metropolitan area with at least 20 Latino students in fifth grade, the target age group. Prior to selecting potential schools to include in the study, the cultural context of each of these communities was scored. Cultural context was operationalized using multiple indicators: (a) the Mexican–American population density; (b) the percentage of elected and appointed Latino office holders; (c) the number of churches providing services in Spanish; (d) the number of locally owned stores selling traditional Latino foods, medicines, and household items; and (e) the presence of traditional Mexican-style stores (e.g., carnicerías). The score from each indicator was standardized and summed to create a community cultural context score. Next, the 237 school communities were arranged from lowest score to highest (i.e., from low to high levels of support for Mexican culture). The five “outliers” on the high end of the scale were selected because they represented particularly interesting living contexts (Mexican ethnic enclaves). Next, 25 additional schools were systematically selected from the remainder of this list by choosing a random starting point within the 10 lowest scores and selecting every 9th score (school) thereafter to represent the complete spectrum of community contexts. In total, 47 schools from 18 public school districts, the Catholic Diocese, and alternative schools were selected and organized into 42 distinct, noncontiguous communities. The communities sampled included semirural, suburban, urban, and inner city neighborhoods; 44.7% of schools were categorized as large urban schools, 6.4% midsize urban, 36.2% large suburb, 6.4% small suburb, 2.1 rural fringe, and 4.3% rural distant (National Center for Education Statistics 2006). The mean percent of students eligible for free/reduced lunch at these schools was 67.3% (SD = 27.1), with a low of 7.5% and a high of 100%. Proportion of Hispanics in these schools ranged from 15 to 98% with a mean of 70% (SD = .237).

Recruitment materials (in English and Spanish) were sent home with all 5th grade children in selected schools that explained the research project and asked parents to indicate whether they were interested in participating. Interested families were screened if their ethnicity was Hispanic or they had Hispanic/Latino surnames. Over 85% of those who returned the recruitment materials were eligible for screening (e.g., Hispanic) and 1,028 met study eligibility criteria. In-home Computer Assisted Personal Interviews were then scheduled; 750 families (mothers and child required, fathers optional) completed interviews, 73% of those eligible. Cohabitating family members’ interviews were conducted concurrently by professionally trained interviewers in different locations at their home. Interviewers read each survey question and possible response aloud in participants’ preferred language to reduce problems related to variations in literacy levels. Families were paid $45 and $50 per participating family member at Time 1 and 2, respectively.

Measures

Participants were asked a series of demographic questions including annual family income (“estimate your total family income for the past year,” with response options ranging from 1 = $0,000–$5,000 to 20 = 95,001 ?), years of education, and nativity (“in what country were you born?”, 1 = U.S., 2 = Mexico). Consistent with prior research, neighborhoods were operationalized at the level of the census block group (Deng et al. 2006) which contain approximately 1,500 residents and are delineated with the assistance of local participants to enhance their relevance as an identifiable geographic space (U.S. Census Bureau 2000). There were a total of 259 neighborhoods represented in the current study with a mean of 2.9 families per neighborhood (range of 1–17).

Perceived Economic Hardship

Mothers and fathers reported their subjective economic hardship using three subscales reflecting (a) an inability to make ends meet (2 items), (b) not enough money for necessities (7 items), and (c) financial strain (2 items). Items on these subscales are either directly from or derived from the economic hardship and economic pressure subscales developed by Conger et al. (1994). The mean of the three subscales was computed to derive an economic hardship score for mothers and fathers (separately) with higher scores reflecting greater economic hardship. This scale was validated in prior research with Mexican–American parents (Barrera et al. 2001) and demonstrated good reliability among mothers (α = .76 English, .75 Spanish) and fathers (α = .82 English, .76 Spanish) in the current sample.

Neighborhood Disadvantage

For each neighborhood (census block group), 2000 U.S. Census data of (a) the percent of families below poverty level, (b) percent of families headed by a single female, (c) percent of males unemployed, (d) percent of people with less than a HS education, and (e) percent of families on assistance were used as indicators of neighborhood disadvantage. All are common indicators of disadvantage in the neighborhood (Deng et al. 2006). The neighborhood disadvantage score is the average of the standardized score for the five indicators; this score ranged from −1.31 to 4.32 across all neighborhoods represented in the study, with a mean of .05 (SD = .75) for the full sample and −.02 (SD = .67) for the father subsample.

Perceived Neighborhood Danger

Mothers and fathers reported on their own perceptions of the degree of danger in their neighborhoods using a 3-item subscale of the Neighborhood Quality Evaluation Scale (NQES, Roosa et al. 2005). Individuals were asked to indicate their levels of agreement ranging from (1) not true at all to (5) very true on items such as “It is safe in your neighborhood” (reverse coded). Higher scores reflect a higher sense of perceived danger. This is the only known neighborhood perceptions measure with evidence of cross-cultural and cross-language (English/Spanish) equivalence (Kim et al. in press). Cronbach’s alphas were high for mothers (α = .92 English, .87 Spanish) and fathers (α = .86 English, .87 Spanish) in the current study.

Neighborhood Familism

Mothers and fathers reported on their own familism values by responding to the familism subscale of the Mexican–American Cultural Values Scale (MACVS, Knight et al. in press) that tapped three dimensions: support and emotional closeness (6 items; e.g., “Parents should teach their children that family always comes first”), obligations (5 items; e.g., “If a relative is having a hard time, one should help them out if possible”), and family as a referent (5 items; “It is important to work hard and do one’s best because this work reflects on the family”). Participants rated how much they agreed or disagreed with each item with responses ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely). Cronbach’s alphas for overall familism were .75 for mothers and .79 for fathers. Mother and father scores (if available) were averaged to produce a familism score for each family. Neighborhood familism scores were then calculated by taking a mean of these family scores in a given neighborhood (census block group). Neighborhood familism ranged from 3.25 to 4.97, with a mean of 4.38 (SD = .20) for the full sample and 4.39 (SD = .19) for the father subsample.

Parenting Behavior

Parents reported on their own parenting behavior using the Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI) originally developed by Schaefer (1965) and subsequently adapted for use with culturally diverse parents (see White et al. 2009, for description of adaptations). The CRPBI has demonstrated cross-cultural and cross language equivalence (Knight et al. 1992, 1994). The warmth subscale is a self-report measure on which parents reported how often they performed a list of eight behaviors in relation to their adolescent in the past month on a 5-point Likert scale from almost never to almost always. Harsh parenting consisted of eight items administered with the same response format. Cronbach’s alphas for warmth ranged from .72 to .85 for mothers and fathers (English and Spanish); the range for harsh parenting was .71–.73.

Child Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms

We used symptoms counts from the computerized version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; Shaffer et al. 2000) to assess psychiatric symptoms. The DISC has been successfully translated into Spanish (Bravo et al. 2001, 1993), and adequate reliability and validity have been reported for use with Mexican–American youth (Roberts and Roberts 2006). Mother and child were administered the DISC independently and their reports were combined such that a given symptom was considered present if reported by either respondent (Shaffer et al. 2000). This accepted method of combining reporters is different than averaging scores across parent and child or deriving multiple reporter latent constructs (as is often done with behavioral rating scales), because it uses diagnostic data from each reporter to derive a single count of symptoms (e.g., Garland et al. 2001). Symptom counts for anxiety and mood disorders were summed to represent internalizing problems, and symptom counts for conduct disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders, and oppositional defiant disorders were summed to represent externalizing problems.

Results

Analytic Plan

The longitudinal model shown in Fig. 1 was estimated in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2007) using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. FIML estimation uses all available observations and provides unbiased estimates of model parameters in the presence of missing data. The multi-level nature of the data (i.e., multiple families from the same neighborhood) was accounted for by the software; standard errors of path coefficients are adjusted to account for neighborhood clustering. All context and parenting variables were assessed at Time 1 to examine their effects on Time 2 internalizing and externalizing symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms. All variables were standardized (i.e., converted to z-scores) based on the means and standard deviations at the individual family level rather than at the neighborhood level. Two separate models were estimated to test the effects of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting as a mediator of family and neighborhood context. Separate models enabled us to retain a larger, more representative sample (including single mothers) for the mother report model. Both models included the same objective measures of context and mental health outcomes. Given interest in the effects of parents’ perceptions on their own parenting, mothers’ and fathers’ self reports of subjective economic hardship, perceived neighborhood danger and parenting were used in their corresponding models. Parent nativity and child gender were included as covariates on parenting variables and mental health outcomes; direct effects from contextual predictors (neighborhood disadvantage, neighborhood familism, and economic hardship) to mental health outcomes were included.

Interaction terms were created by calculating the product of the two (standardized) variables of interest and using the product as a manifest variable (Tein et al. 2004). Follow up analyses for interactions were conducted according to Aiken and West (1991). Mediation effects were tested using the product of coefficients method with the multivariate delta method of deriving the standard error (Sobel 1982). This test is somewhat conservative, but has excellent power in samples of this size (MacKinnon et al. 2002). Standardized path coefficients are presented for models. Standardized path coefficients can be interpreted as the number of standard deviations change in the outcome for a 1 standard deviation change in the predictor; standardized path coefficients can be interpreted like other similar standardized effect sizes such as Cohen’s d. Good (acceptable) model fit is reflected by a non-significant chi-square test, CFI greater than .95 (.90), RMSEA less than .05 (.08), and SRMR less than 0.05 (0.08) (Hu and Bentler 1999; Kline 2005). Multiple fit indices are used because no single indicator is unbiased in all analytic conditions.

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Intercorrelations are presented in Table 2 with variables used in the mother report model in the upper triangle and those for father report in the lower triangle. For mothers, the nativity covariate correlated with all four indicators of contextual risk (income, economic hardship, neighborhood disadvantage, perceived neighborhood danger), neighborhood familism, and adolescent externalizing at Time 1 and Time 2. Father’s nativity correlated with all four indicators of contextual risk and neighborhood familism. Though positively correlated with all other contextual predictors, family income was not related to any parenting mediators or mental health outcomes. Thus, family income was dropped from the models presented below; when models were run with income included, analyses confirmed it was not a significant predictor and its exclusion did not change substantive findings. Although neighborhood disadvantage was not correlated with any parenting or mental health measures, it was retained to test for hypothesized interaction effects.

Table 2.

Correlations of variables in the mother-report model (upper triangle) and father-report model (lower triangle)

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family i–ncome | – | −0.50** | −0.33*** | −0.21*** | −0.18*** | −0.39*** | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| 2. Subjective economic hardship | −0.52*** | – | 0.19*** | 0.17*** | 0.05 | 0.18*** | −0.01 | −0.10** | 0.11** | 0.14*** | 0.10*** | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| 3. Neighborhood disadvantage | −0.35*** | 0.16*** | – | 0.29*** | 0.16*** | 0.14*** | −0.11** | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| 4. Perception of neighborhood danger | −0.30*** | 0.30*** | 0.35*** | – | −0.01 | 0.10** | −0.11** | −0.08* | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| 5. Average neighborhood familism | −0.21*** | 0.07 | 0.17*** | 0.08 | – | 0.14*** | −0.08* | 0.15*** | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.10** |

| 6. Parent nativity | −0.50*** | 0.26*** | 0.15*** | 0.20*** | 0.12** | – | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.14*** | −0.01** |

| 7. Child gender | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.05 | – | −0.09* | 0.14*** | −0.07 | −0.09* | 0.13*** | 0.10** |

| 8. Parental warmth | 0.05 | −0.16 | −0.01 | −0.21*** | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.02 | – | −0.15*** | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.16*** | −0.23*** |

| 9. Harsh parenting | −0.05 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.07 | – | 0.13*** | 0.11** | 0.21*** | 0.21*** |

| 10. Internalizing symptoms—Time 1 | −0.06 | 0.21*** | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.10* | −0.07 | 0.06 | – | 0.45*** | 0.50*** | 0.25*** |

| 11. Internalizing symptoms—Time 2 | −0.02 | 0.10* | −0.00 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.11* | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.46*** | – | 0.31*** | 0.53*** |

| 12. Externalizing symptoms—Time 1 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.12** | −0.15*** | 0.19*** | 0.46*** | 0.29*** | – | 0.54*** |

| 13. Externalizing symptoms—Time 2 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.09 | −0.08 | −0.06 | 0.10* | −0.16** | 0.20*** | 0.24*** | 0.52*** | 0.49*** | – |

Sample size ranges from 702 to 750 for time 1 variables and from 673 to 709 for time 2 variables for mother-report model variables. Sample size ranges from 440 to 467 for time 1 variables and from 416 to 440 for time 2 variables for father-report model variables. Parent nativity is coded 1 = U.S., 2 = Mexico. Gender is coded 1 = female, 2 = male

p <.05;

p <.01

p <.001

Intraclass correlations (ICCs) for individual level variable were calculated to assess the proportion of variation in these variables attributable to neighborhood clustering. About 22% of the variation in father’s perception of neighborhood danger, about 17% in mother’s perception of neighborhood danger, and about 14% in mother’s assessment of economic hardship was attributable to neighborhood; all other individual-level variables had ICCs of 7% or less.

Multi-group models with child gender as the grouping variable were examined to determine how child gender may differentially affect the paths in the model. For the mother and father models, two multi-group models were compared: a fully fixed model in which all model paths were constrained to be the same for boys and girls and a fully free model in which all model paths were allowed to vary between boys and girls. Nested model tests comparing these two models indicated that the fully free model did not fit significantly better than the fully fixed model (χ2(26) = 35.728, NS for mother model, χ2(26) = 18.692, NS for father model). This suggests that the paths in the model do not differ significantly across child gender. Thus, all models presented in this paper are single-group models with child gender included as a covariate.

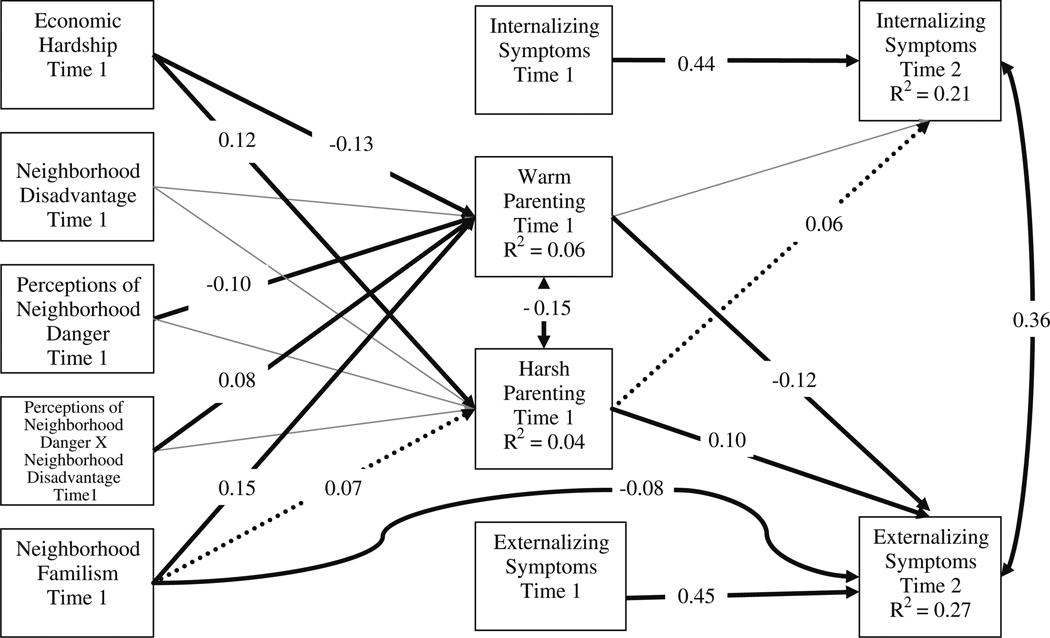

Test of Hypothesized Model

The fit of the hypothesized mother-report model was good (χ2(10) = 59.361, p < .0001; CFI = 0.937; RMSEA = 0.081; SRMR = 0.032). Figure 2 shows the results for this model. Paths from covariates (mother nativity and child gender) to parenting variables and mental health outcomes were included in the model but are not shown in Fig. 2. All direct paths from contextual predictors to mental health outcomes were included in the model but only significant paths are shown in Fig. 2. Mother’s subjective economic hardship was negatively related to maternal warmth and positively related to harsh parenting. Neighborhood familism was positively related to maternal warmth. Mother’s perception of neighborhood danger was negatively related to maternal warmth, but also interacted with neighborhood disadvantage to affect maternal warmth. Prospective effects of maternal parenting on adolescent mental health were found. Specifically, maternal warmth was negatively related and maternal harsh parenting was positively related to externalizing symptoms. Only one prospective direct path from context to mental health was significant; there was a negative direct path from neighborhood familism to Time 2 externalizing symptoms. Given the general absence of direct context effects on mental health, a model was tested in which all the non-significant direct paths were removed and this did not result in any substantive changes in the direction or significance of paths in the model.

Fig. 2.

Results for mother-report model showing standardized path coefficients. Note. Maternal nativity and child gender covariates are not included in the figure. Non-significant direct paths from neighborhood disadvantage, economic hardship, and neighborhood familism to internalizing and externalizing are not shown. Significant (p < .05) paths are bolded lines; marginal (.05 < p < .10) paths are dashed; non-significant paths are light, solid lines

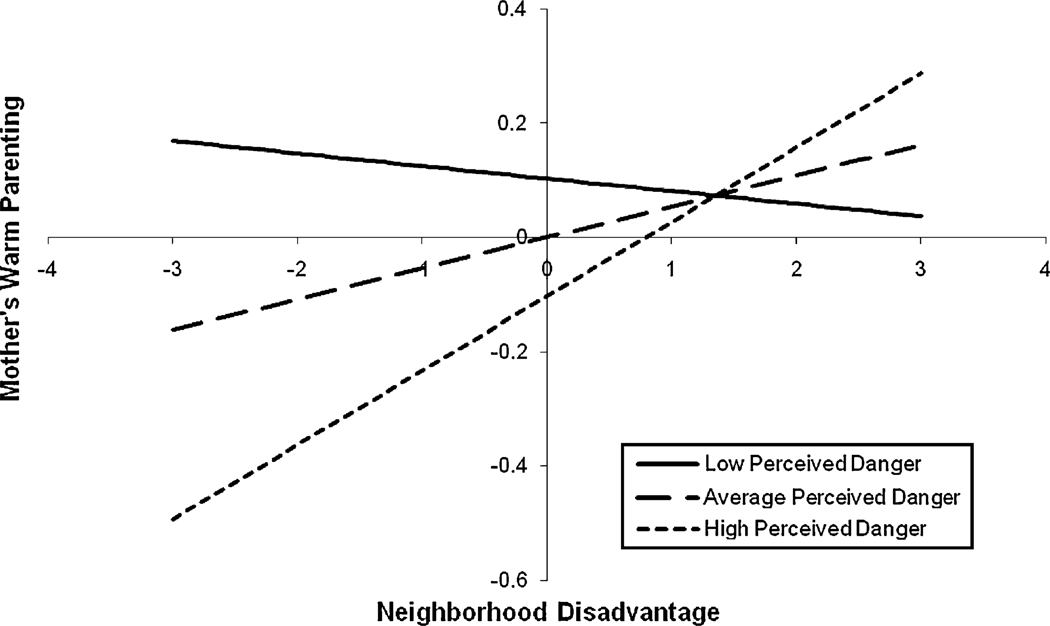

Figure 3 shows a simple slope plot of the interaction between neighborhood disadvantage and mother’s perceptions of neighborhood danger on maternal warmth. The pattern of the interaction was such that there was no relation between neighborhood disadvantage and maternal warmth when mothers perceived the neighborhood was average in danger (mean of neighborhood danger, z = 1.444, NS) or low in danger (1 standard deviation below the mean of perceived neighborhood danger, z = −.467, NS), but there was a positive relation when mothers perceived the neighborhood was high in danger (1 standard deviation above the mean of perceived neighborhood danger, z = 2.866, p < .01).

Fig. 3.

Interaction of neighborhood danger and mother’s perceptions of neighborhood danger on mother’s warm parenting

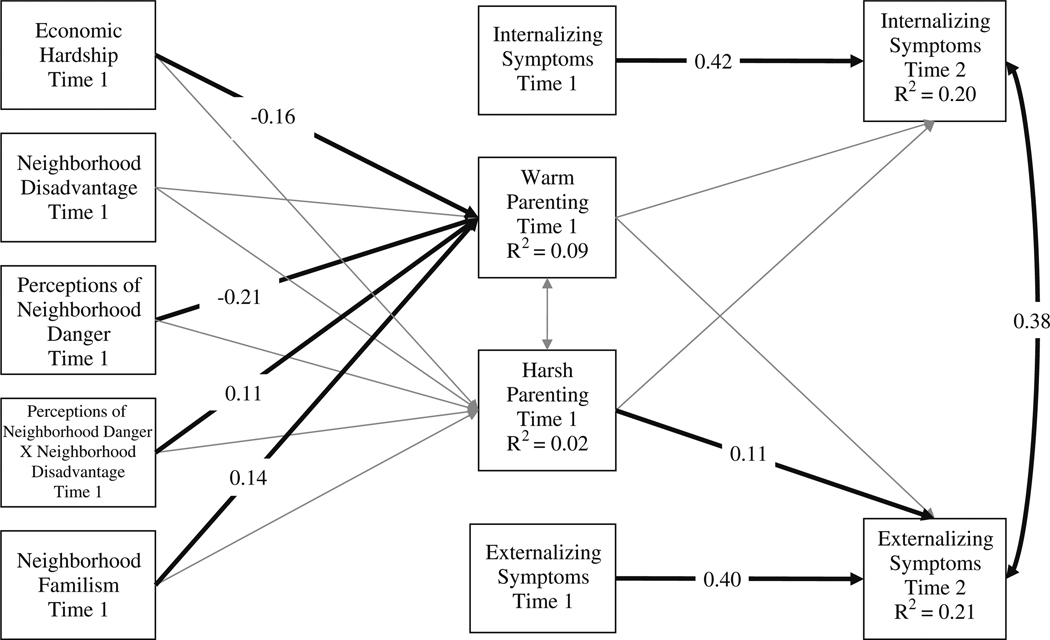

The fit of the hypothesized father-report model shown in Fig. 4 was good (χ2(10) = 34.784, p < .01; CFI = 0.937; RMSEA = 0.073; SRMR = 0.030). Paths from covariates (father nativity and child gender) to parenting variables and mental health outcomes were included in the model but are not shown in Fig. 4. Direct paths from contextual predictors to mental health outcomes were included in the model but are not shown in Fig. 4. Fathers’ subjective economic hardship was negatively related to paternal warmth and marginally positively related to paternal harsh parenting. Average neighborhood familism was marginally positively related to paternal warmth. Father’s perception of neighborhood danger was negatively related to paternal warmth, but also interacted with neighborhood disadvantage to affect paternal warmth. Paternal harsh parenting showed positive prospective effects on externalizing symptoms. The direct path from neighborhood familism to Time 2 externalizing was marginal and negative. A model in which these non-significant direct paths were removed did not result in any substantive changes in the direction or significance of paths in the model.

Fig. 4.

Results for father-report model showing standardized path coefficients. Note. Paternal nativity and child gender covariates are not included in the figure. Non-significant direct paths from neighborhood disadvantage, economic hardship, and neighborhood familism to internalizing and externalizing are not shown. Significant (p < .05) paths are bolded lines; marginal (.05 < p < .10) paths are dashed; non-significant paths are light, solid lines

Simple slopes plots of the interaction between neighborhood disadvantage and father’s perceptions of neighborhood danger on paternal warmth were nearly identical to the plots for mother report shown in Fig. 3. The pattern was such that there was no relation between neighborhood disadvantage and paternal warmth when fathers perceived the neighborhood was average in danger (mean of perceived neighborhood danger, z = 1.079, NS) or low in danger (1 SD below the mean of perceived neighborhood danger, z = −0.996, NS), but there was a positive relation when fathers perceived the neighborhood was high in danger (1 SD above the mean of perceived neighborhood danger, z = 2.603, p < .01).

Test of Mediation

Significant mediation effects were found in the mother-report model only. Subjective economic hardship had a positive effect on externalizing symptoms through maternal warmth (z = 2.125, p < .05) and maternal harsh parenting (z = 2.108, p < .05). Neighborhood familism had a negative effect on externalizing symptoms through maternal warmth (z = −2.509, p < .05). The interaction of neighborhood disadvantage and perceptions of neighborhood danger had a negative effect on externalizing symptoms through maternal warmth (z = −2.100, p < .05). The nature of this interaction effect was such that the indirect effect from neighborhood disadvantage to maternal warmth to externalizing depended on the mother’s perceived neighborhood danger. Neighborhood disadvantage had a negative effect on externalizing through maternal warmth when mothers perceived the neighborhood as high in danger (1 SD above the mean of neighborhood danger, z = −2.144, p < .05) and non-significant effects when mothers perceived the neighborhood as average (mean of neighborhood danger, z = −1.301, NS) or low in danger (1 SD below the mean of neighborhood danger, z = 0.464, NS). The overall mediated effect of mother’s perceptions of neighborhood danger on externalizing symptoms via warm parenting was positive (z = 2.025, p < .05).

Adolescent Perceptions of Parenting

Because the central focus of this study was to examine parents’ responses to neighborhood risk based on their own evaluations of their neighborhoods and the behaviors they enact in response to these risks, their self reports of parenting were used to provide the best test of this question. However, adolescent reports of parenting were also available for our sample and raise the question of whether findings would be validated if these reports were used instead or in combination with parent report of parenting. Adolescents’ reports of parenting did not correlate with parents’ reports at a magnitude that would support a composite or latent construct. Thus, we evaluated a mother and a father model in which adolescent report of warm parenting and harsh parenting were added to the models presented above, acting as additional mediators between neighborhood variables and symptoms in these models. Although the additional of adolescent report of parenting did not change any of the aforementioned findings of either model, these models showed minimal effects of context on adolescent report of parenting and no relations between adolescent report of parenting and adolescent mental health. Because they do not contribute substantively to the current study, these additional models are not presented but should be considered when interpreting the current findings.

Discussion

This study’s primary aim was to test the role of parenting as a mediator of the effects of family and community economic disadvantage on adolescent mental health, using parents’ own reports of their parenting behavior. Guided by a cultural ecological framework, the study examined multiple, overlapping contextual influences relevant to low-income status to determine how they operate together to shape parenting and ultimately affect adolescent mental health. The study was unique in its inclusion of neighborhood cultural values when modeling family and neighborhood effects, offering one of the first attempts to test the protective role of cultural values at the neighborhood level. Findings supported parenting as a mediator and showed that family and neighborhood economic conditions uniquely impact parenting behavior in Mexican–American families. However, as discussed in greater detail below, evidence for indirect effects (parenting mediation) on mental health were supported for mothers but not fathers, and parenting effects on mental health were found for externalizing but not internalizing symptoms.

Economic Hardship and Disrupted Parenting

Although family income was not related to parenting or adolescent mental health, mothers’ subjective economic hardship was associated with lower levels of maternal warmth and higher levels of maternal harsh parenting. Maternal parenting predicted increased externalizing behaviors, in turn, and tests of mediation showed that indirect paths from economic hardship to adolescent externalizing through maternal warmth and harsh parenting were both significant. Father’s perceptions of economic hardship were related to lower levels of paternal warmth as well, but the relation of paternal warmth to externalizing was not significant, thus explaining why the study failed to find evidence for mediation through father’s parenting. Nevertheless, the significant mediation effects with maternal parenting, and the similar link between paternal economic hardship and parenting are consistent with FST (Conger et al. 1997, 2000). These findings support the view that parenting is compromised in Mexican–American families when parents experience financial strains and pressures due to their economic circumstances. Although similar findings have been reported in prior research with this population (e.g., Barrera et al. 2001; Parke et al. 2004), this is the first of these studies to show that parenting disruptions associated with economic hardship account prospectively for youth mental health. Thus, these findings lend additional support to the causal processes outlined in FST as well as their applicability to Mexican–American adolescents. However, it is important to note that our test of FST processes was limited in its focus on parenting and did not test the full chain of family stress processes, such as the intervening role of marital conflict, that are hypothesized to account for family economic hardship effects on children’s psychological problems.

Neighborhood Effects on Parenting and Mental Health

Neighborhood scholars have proposed that subjective perceptions of the neighborhood may be more impactful than objective indicators and that greater understanding of neighborhood effects may be possible by studying both types of neighborhood indicators together (Cook et al. 1997; Roosa et al. 2009). The current study offered evidence to support both assertions. Tests of interactions between the objective and subjective neighborhood indicators produced the study’s most novel and surprising effects. Consistent with neighborhood socialization theory, mothers’ subjective perceptions of neighborhood danger were associated with lower levels of maternal warmth, theoretically due to the disruptive effects of living in a stressful and threatening environment (Sampson et al. 1997). However, for a subset of parents that had the most heightened concerns about neighborhood danger, objective indicators of neighborhood disadvantage were positively associated with parental warmth, and this pattern was replicated with both mothers and fathers report of their own parenting. Further, when mothers perceived high levels of neighborhood danger, census indicators of neighborhood disadvantage were indirectly linked (through maternal warmth) to decreased externalizing in early adolescence.

These findings suggest that neighborhood effects may be conditioned in important ways on parents’ subjective evaluations and individual experiences in their neighborhoods. It is possible that some parents are more acutely aware of neighborhood dangers, and may have extra motivation to provide warm, responsive parenting due to greater concern for their children’s safety. This interpretation is consistent with findings in the empowerment literature that have shown that perceptions of environmental problems can serve as a motivator to action (Maton and Rappaport 1984). For example, some studies find parents in high risk neighborhoods keep children closer to home, chaperone them more closely in the neighborhood, or proactively seek out alternative environments for their children outside the neighborhood context (Burton 1991; Furstenberg et al. 1998; Punteney 1997). Studies with African Americans also report parents may use more restrictive, harsh discipline strategies under these circumstances (Mason et al. 1996), but this was not shown here. While it is impressive that the interactive neighborhood effects on parental warmth were found for both mothers and fathers, this is a novel finding and should be replicated. If supported in subsequent studies, it potentially offers a more nuanced understanding of parenting in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Although most neighborhood research has studied risky conditions and processes almost exclusively, the current study operationalized traditional Latino family values at the neighborhood level, using the census block group as the neighborhood unit. Neighborhood familism showed the most robust effects of all contextual predictors. It was positively related to maternal and paternal warmth and, in turn, showed indirect effects through maternal warmth to predict lower externalizing symptoms. Moreover, neighborhood familism was the only contextual predictor that had prospective, direct effects on adolescent mental health (externalizing) after controlling for all other context and parenting effects. A number of mechanisms may explain how shared familism values may protect adolescents from engaging in problem behaviors. A community with uniformly high, shared values that center on the importance of family can validate and support parents’ commitment to family, thereby helping them to maintain positive parenting practices and family relationships. These communities can also offer parental and kin support, relationship networks that provide collective supervision and resources for youth to pursue goals, positive opportunities, safe places, and norms that emphasize education, social control, and rule enforcement (Aber et al. 1997; Benson et al. 1998; Jessor 1993; Sampson et al. 1997). Denner et al. (2001) conducted qualitative interviews with residents in poor communities that had significantly lower teen birth rates compared to other similarly poor communities. Residents in these neighborhoods were more likely to be immigrant, Latino, and linguistically isolated, and they reported strong social ties that resulted in the maintenance of traditional values about commitment to family and community, respect for the family and family reputation, close ties to religious institutions, and the control, close monitoring, and protection of adolescents. These researchers concluded that cultural values and norms intersect with social processes in immigrant communities to protect youth from engaging in high risk behaviors. As one of the first quantitative studies to operationalize cultural values at the neighborhood level, the current study supports Denner et al.’s conclusion. However, a limitation of the neighborhood familism measure used in the current study is that parents reported on their own values and did not report directly on cultural values they observed among residents within their neighborhoods. Nevertheless, the study shows that Latino family values are an important protective resource. Future research is needed to better understand at what level they operate and specifically how they influences social processes within diverse neighborhoods.

Context effects on parenting were most pronounced for parental warmth. With the exception of family income, each contextual variable showed a significant association with parental warmth and the pattern of findings was similar for mothers and fathers. In contrast, none of the contextual variables were related to father’s harsh parenting. Although it is tempting to conclude that the lack of mediation through fathers’ parenting is evidence that fathers play a diminished role in adolescent mental health relative to mothers, this explanation would be inaccurate as it does not account for father’s impact in terms of harsh parenting. Although paternal warmth was not related to adolescent outcomes, paternal harsh parenting had significant prospective effects to predict adolescent externalizing symptoms. Further, it is possible the lack of mediation through paternal parenting is due to the smaller sample size and reduced power in the father subsample. Effects on internalizing were not shown for any predictors in this study, however the timing of data collection may not be ideal for detecting such effects. Internalizing symptoms decreased overall for the current sample during the study time frame and a closer examination shows this was the result of a decrease in anxiety symptoms that are more common during childhood. Other internalizing symptoms, particularly depressive symptoms, begin to increase later in adolescence (Lewinsohn et al. 1994), at which point context and parenting effects may be detected in this sample.

Study Limitations and Contributions

The current study should be viewed in light of its limitations, including the small effect sizes associated with most paths, altogether accounting for roughly four to six percent of variance in mothers’ parenting, two to nine percent in father’s parenting, and twenty to twenty seven percent in adolescent mental health symptoms. These estimates suggest a need to consider other risk and protective processes operating within children’s social ecologies that may account for their mental health outcomes, such as other family or peer processes that may operate independently or interactively with neighborhood processes. Although the use of prospective data is an important contribution, given the near absence of such data for Mexican–American youth, the mediation effects were tested with only two waves of data. Thus conclusions about causality between context and parenting must be tempered, especially for the subjective indicators, since both were measured at the same time point. Moreover, with only two waves of data yet available for the sample, it was not possible to test more complex, reciprocal effects involving neighborhood, parenting and child outcome that are consistent with ecological theory. Method variance also is a concern in these relations and in the link between parenting and adolescent mental health, particularly given the lack of replication of findings when adolescent reports of parenting were used. The use of both mother and adolescent report to assess internalizing and externalizing symptoms reduces this concern somewhat, but also suggest the weaker effects found in the father model may have resulted from the lack of father report of symptoms.

Despite these limitations, the study had several notable strengths, including use of prospective data, a focus on both mothers and fathers, and integration of family and neighborhood research traditions. The study also employed a sampling plan that was unique in the neighborhood literature because “culture” was a core dimension driving selection of communities included in the study. This type of design is ideally suited to identify and understand community cultural processes because it provides the variability in cultural context needed to test hypothesized effects. Further, by sampling a broad array of neighborhood types, spanning central urban to rural communities, we were able to achieve greater variability on family demographic variables, particularly on socioeconomic status, than is typical in research with Mexican–American families. Though rarely used, such a design is becoming increasingly important because the Mexican–American population shows vast diversity and has migrated to widely divergent geographic locations and communities across the U.S. Emerging evidence suggests that risk and protective processes associated with Latino cultural adaptation can vary widely depending on the extent to which traditional culture is supported, treated with hostility, or absent within receiving communities (Gonzales et al. 2009; Portes and Zady 2002). Thus, failure to account for cultural differences at the community level may limit understanding of how unique social processes operating within diverse communities can offset or amplify family and community economic conditions.

The cultural ecological framework guiding this study also represents an advance in the study of culture. In much of the prior research, studies have examined “cultural” variables, such as immigrant status or acculturation level as predictors in isolation of other key cultural and context variables. Broader contributing factors, such as location or type of residential community, have often been omitted, along with critical demographic confounds (e.g., socioeconomic status), leading to a literature that has been rife with inconsistent findings (Rogler et al. 1991). Studies also have failed to identify underlying cultural processes beyond demographic markers or language that can provide modifiable targets for social action. In contrast, the current study included multiple, overlapping cultural-contextual influences to capture “culture” more broadly, to test a process model by which these influences combine to impact adolescent mental health prospectively, and to control for confounding relations among these variables. As a result, the significant prospective effects of community cultural values were not confounded in this study with family immigrant status or socioeconomic status, but were shown to be uniquely important to the prediction of adolescent externalizing behaviors. However, as noted earlier, the model that was tested was limited, and did not simultaneously capture additional cultural variables (e.g., acculturative stress) or settings (e.g., peers, schools) that might also be included in research with Mexican–American youth. Nevertheless, our theoretically driven process model provides one example of research that moves toward a more comprehensive, multilayered conceptualization of culture and its intersection with community context.

The study’s conceptual framework also offered an important new dimension to the study of neighborhood effects. Although a considerable body of empirical research has shown a strong connection between neighborhood disadvantage and low neighborhood social cohesion, qualitative studies with Latino immigrant populations have described social and cultural resources in economically poor communities and have raised questions about the relevance of the underclass concept for immigrant Latino communities (Menjivar 1997; Velez-Ibanez 1993). These studies suggest community processes may differ for Latino populations because they often reside in ethnically segregated neighborhoods that are poor and lacking in resources, yet manage to maintain strong networks of support and shared values among residents (Cooper et al. 1999; Portes and Zhou 1993). Our findings provide some support for this perspective and highlight the importance of assessing the cultural characteristics of communities to understand how residents in poor communities use cultural resources to manage environmental challenges. Future research should identify other cultural characteristics that may serve as community resources for Mexican–Americans, as well as for other minority groups, and examine whether and how they facilitate critical processes of interest in community psychology, including community involvement, citizen participation, and community empowerment (Florin and Wandersman 1990).

Results from this study have implications for interventions to reduce adolescent problem behaviors in disadvantaged communities. At a basic level, this study suggests that parental warmth and harsh parenting are important influences for Mexican–American youth, and that parenting interventions are a viable strategy to reduce externalizing problems for Mexican–American youth in high risk communities (e.g., Martinez and Eddy 2005). Findings also suggest it may be useful to increase parents’ awareness of neighborhood risks and their motivation to be proactive in protecting their children. However, the current findings also place parenting within a broader context and highlight a need to support policies and intervention that strengthen protective neighborhood resources, particularly those cultural strengths that may exist within traditionally oriented Mexican–American communities. In a study of inner-city youth in Chicago, Sheidow et al. (2001) found that positive family functioning is only effective at reducing youth exposure to community violence if community level protective processes are also in place within these communities. Thus, strategies that strengthen family processes while simultaneously building shared community cultural values and support, may be an especially potent approach to use when planning family-focused programs and other services for Mexican–American families. However, a remaining challenge for community psychology is to understand the conditions that can promote and maintain shared cultural values and strong sense of community in neighborhoods that lack these resources (Florin and Wandersman 1990). Further, if shared values are accompanied by isolation from the broader community, as is the case for some immigrant communities, the reduced risk for youth problem behavior may come at a cost of reduced integration and access to other important resources for positive youth development. This possibility and strategies to build strong bicultural communities are topics to explore in future research that combines community and cultural perspectives.

Acknowledgements

Work on this paper was supported, in part, by grant MH 68920 (Culture, context, and Mexican–American mental health), grant T-32-MH18387 to support training in prevention research, and the Cowden Fellowship program of the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. The authors are thankful for the support of Marisela Torres, Jaimee Virgo, our Community Advisory Board and interviewers, and the families who participated in the study.

Contributor Information

Nancy A. Gonzales, Email: nancy.gonzales@asu.edu, Department of Psychology, Arizona State Univeristy, P.O. Box 871104, Tempe, AZ 85287-1104, USA.

Stefany Coxe, Department of Psychology, Arizona State Univeristy, P.O. Box 871104, Tempe, AZ 85287-1104, USA.

Mark W. Roosa, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Rebecca M. B. White, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

George P. Knight, Department of Psychology, Arizona State Univeristy, P.O. Box 871104, Tempe, AZ 85287-1104, USA

Katharine H. Zeiders, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Delia Saenz, Department of Psychology, Arizona State Univeristy, P.O. Box 871104, Tempe, AZ 85287-1104, USA.

References

- Aber JL, Gephart MA, Brooks-Gunn J, Connell JP. Development in context: Implications for studying neighborhood effects. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty: Context and consequences for children. Russell Sage: New York; 1997. pp. 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, Polo A, Cao Z, Canino G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:68–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, Brown JR. Latino immigrant parents’ beliefs about the “Path of Life” of their adolescent children. In: Contreras J, Neal-Barnett A, Kerns K, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2002. pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr, Caples H, Tein J. The psychological sense of economic hardship: Measurement models, validity, and crossethnic equivalence for urban families. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:493–517. doi: 10.1023/a:1010328115110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr, Prelow HM, Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Michaels ML, et al. Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents’ distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family, and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Benson PL, Leffert N, Scales PC, Blyth DA. Beyond the “village” rhetoric: Creating healthy communities for children and adolescents. Applied Developmental Science. 1998;2:138–159. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Frank E, Jensen PS, Hessler RC, Nelson CA, Steinberg L, et al. Social context in developmental psychopathology: Recommendations for future research from the MacArthur Network on Psychopathology and Development. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:143–164. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo M, Woodbury-Farina M, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M. The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in Puerto Rico. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1993;17:329–344. doi: 10.1007/BF01380008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo M, Ribera J, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Shrout PE, Ramirez R, et al. Test-retest reliability of the Spanish version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:433–444. doi: 10.1023/a:1010499520090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM. Everyday life in two high-risk neighborhoods: Caring for children. The American Enterprise. 1991;2:34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Garcia Coll C. Latino fathers: Uncharted territory in need of much exploration. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4th ed. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley; 2004. pp. 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo RM, McLoyd VC. Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development. 2002;73:1310–1321. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US. Appendix A: Census 2000 geographic terms and concepts. DC: Washington: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance Summaries. MMWR. 2006 June 9;55 (No. SS-5) [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Diaz L. Culturally relevant issues and treatment implications for Hispanics. In: Salett EP, Koslow DR, editors. Crossing cultures in mental health. Washington, DC: SIETAR; 1989. pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ. Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr . Families in troubled times. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge XJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH. Family economic hardship and adolescent adjustment: Mediating and moderating processes. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 288–310. [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Rueter MA, Conger RD. The role of economic pressure in the lives of parents and their adolescents: The family stress model. In: Crockett LJ, Silbereisen RK, editors. Negotiating adolescence in times of social change. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Cook TD, Shagle SC, Degirmencioglu SM. Capturing social process for testing meditational models of neighborhood effects. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty: Context and consequences for children. New York: Russell Sage; 1997. pp. 94–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CR, Denner J, Lopez EM. Cultural brokers: Helping Latino children on pathways toward success. The Future of Children. 1999;9:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Davis KD, Updegraff K, Delgado M, Fortner M. Mexican American fathers’ occupational conditions: Links to family members’ psychological adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:843–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Abraham WT, Gardner KA, Melby JM, Bryant C, et al. Neighborhood context and financial strain as predictors of marital interaction and marital quality in African American couples. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:389–409. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Ivy L, Petrill SA. Maternal warmth moderates the link between physical punishment and child externalizing problems: A parent-offspring behavior genetic analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2006;6:59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Wallace JM, Jr, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. The epidemiology of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use among Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban American, and other Latin American eighth-grade students in the United States: 1991–2002. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:696–702. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Lopez V, Roosa MW, Ryu E, Burrell GL, Tein JY, et al. Family processes mediating the relationship of neighborhood disadvantage to early adolescent internalizing problems. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2006;26:206–231. [Google Scholar]

- Denner J, Kirby D, Coyle K, Brindis C. The protective role of social capital and cultural norms in Latino communities: A study of adolescent births. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Eamon MK, Mulder C. Predicting antisocial behavior among Latino young adolescents: An ecological systems analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:117–127. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin P, Wandersman A. An introduction to citizen participation, voluntary organizations, and community development: Insights for empowerment through research. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;18:41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FFJ. How families manage risk and opportunity in dangerous neighborhoods. In: Wilson WJ, editor. Sociology and the public agenda. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. pp. 231–258. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg R, Jr, Cook T, Eccles J, Elder G, Sameroff A. Managing to make it: Urban families in high risk neighborhoods. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Garland A, Hough R, McCabe K, Yeh M, Wood P, Aarons G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:409–418. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Fabrett FC, Knight GP. Acculturation, enculturation and the psychological adaptation of Latino youth. In: Villaruel FA, Carlo G, Azmitia M, Grau J, Cabrera N, Chahin J, editors. Handbook of US Latino Psychology. New York: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Germán M, Fabrett FC, Meza C. US Latino Youth. In: Chang EC, Downey CA, editors. Mental health across racial groups: Lifespan Perspectives. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analyses: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huie SA, Hummer RA, Rodgers RG. Individual and contextual risks of death among race and ethnic groups in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:359–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Successful adolescent development among youth in high risk settings. American Psychologist. 1993;48:117–126. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Nair RL, Knight GP, Roosa MW. Measurement equivalence of neighborhood quality measures for European American and Mexican American families. Journal of Community Psychology. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20257. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Tein J, Shell R, Roosa MW. The cross-ethnic equivalence of parenting and family interaction measures among Hispanic and Anglo-American families. Child Development. 1992;63:1392–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Virdin LM, Roosa MW. Socialization and family correlates of mental health outcomes among Hispanic and Anglo American children: Consideration of cross-ethnic scalar equivalence. Child Development. 1994;39:212–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds D, Germán M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Major depression in community adolescents-age at onset, episode during, and time to recurrence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:809–818. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199407000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Marin BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Jr, Eddy JM. Effects of culturally adapted parent management training on Latino youth behavioral health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:841–851. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CA, Cauce AM, Gonzales NA, Hiraga Y. Neither too sweet nor too sour: Problem peers, maternal control, and problem behavior in African American adolescents. Child Development. 1996;67:2115–2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI, Rappaport J. Empowerment in a religious setting: A multivariate investigation. In: Rappaport J, Hess R, editors. Studies in Empowerment: Steps toward understanding action. New York: Haworth; 1984. pp. 37–72. [Google Scholar]

- Menjivar C. Immigrant kinship networks: Vietnamese, Salvadoreans, and Mexicans in comparative perspective. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1997;28:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus user’s guide [Fourth Edition] Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Children in Poverty. Child poverty in the states: Levels and trends from 1979 to 1998. New York: Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Public Elementary/Secondary School Locale Code File: School Year 2003–04, Version 1a (2006) [Retrieved May 30th, 2009];2006 from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/handbook/data/pdf/appendix_d.pdf.

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, et al. Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American Families. Child Development. 2004;75:1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, Jones D. Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 2001;63:941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Zhou M. The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants among post-1965 immigrant youth. Annals of the American Academy of Political Social Science. 1993;530:74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Portes PR, Zady MF. Self esteem in the adaptation of Spanish-speaking adolescents: The role of immigration, family conflict, and depression. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2002;24:296–318. [Google Scholar]

- Punteney DL. The impact of gang violence on the decisions of everyday life: Disjunctions between policy assumptions and community conditions. Journal of Urban Affairs. 1997;19:143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts R. Prevalence of youth-reported DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among African, European, and Mexican American adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1329–1337. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000235076.25038.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]