The numbers are in! Deaths due to cardiovascular disease are declining in the United States.1 That is the good news. The bad news is that cardiovascular mortality in women exceeds that of men.1 One factor contributing to this disparity may be low socioeconomic status, which deters some women from seeking medical care. However, this disparity also reflects basic differences in normal physiology and pathophysiology between males and females that are not well understood and remain understudied.2 The lack of attention to sex differences in etiology of cardiovascular disease has resulted in inadequate methodologies and strategies to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiovascular diseases in women compared with men. For example, physicians routinely order less stress testing and coronary angiography, and treat with less proven medications, in women they believe to have angina.3

This article provides a brief overview of cardiovascular diseases affecting women compared with men, how sex hormones affect vascular function, and illustrative scenarios applicable to reproductive medicine. In this discussion, “sex” is defined by the sex chromosomes and functioning reproductive organs; “gender,” or maleness and femaleness, is defined along a continuum of how an individual functions according to societal attributes or expectations.4

Sex disparity in cardiovascular diseases

Cardiovascular diseases fall into 3 general categories with regard to sex disparity: (1) conditions unique to one sex (erectile dysfunction in men; preeclampsia/hypertension of pregnancy in women, hot flushes of menopause), (2) conditions that occur in both men and women but that have disparate prevalence rates (predominance in females of pulmonary hypertension, Raynaud’s disease, migraine, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome [POTS], atrial fibrillation, ventricular apical ballooning [takotsubo syndrome]; predominance in males of systemic hypertension), and (3) conditions that present differently in women than in men (myocardial infarction symptoms, which in men often include chest and radiating pain, but in women more often include multiple symptoms, including chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, indigestion, and fatigue).5

Conditions unique to one sex

This category is particular to reproductive function. Although erectile dysfunction is not a fatal condition, it may be a symptom of more systemic cardiovascular disease/risk, which could be fatal.6 On the other hand, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including pre-eclampsia, can be fatal if not treated. Even when treated successfully, these hypertensive disorders, as well as gestational diabetes, may double the 10-year risk for adverse cardiovascular events in affected women compared with women who do not have a history of pregnancy disorders.3,7

Conditions occurring in both sexes, with different prevalence

These conditions are complex and may be due, in part, to sex differences in autonomic control of vascular function and stress.8 Much remains to be learned about these disorders, reflecting their complexity, perhaps their female predominance, and the lack of animal models. While these conditions reduce quality of life, they do not carry high mortality.

Conditions that present differently in women than in men

Myocardial infarction is perhaps the most studied adverse event of atherosclerotic ischemic heart disease. Although women present with chest pain as frequently as their male counterparts, they have greater associated symptoms of neck, jaw, and back pain and nausea.5 Differential presentation of ischemic heart disease symptoms reflects differences in the underlying etiology and characteristics of the disease. In men, atherosclerotic lesions are more punctuated, while in women they are more diffuse, often involving the microcirculation. Further, increased microvascular disease may contribute to increased rates of angina and have a greater negative impact on quality of life in women, compared with men, after a myocardial infarction.9

Genetic influences on cardiovascular diseases

The genetic variable underlying sex differences in cardiovascular disease is the complement of sex chromosomes (XX or XY). Genes on the X chromosome affect development of cardiovascular diseases through modulation of mitochondrial function, adiposity, response to hypoxia, apoptosis, and response to androgens.10 Genetic variance in genes on the X chromosome will have greater influence on the physiologic processes and phenotype in males, who have one copy of the gene, compared with females, in whom mosaic inactivation of either the maternal or paternal X will result in greater heterogeneity of phenotype.

An example of this phenomenon is the CAG repeat polymorphism that encodes the transcriptional domain of the androgen receptor. In males, the length of this repeat is associated with androgen receptor activity and levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, abdominal obesity, elevated sympathetic tone, and blood pressure.11 This repeat polymorphism is, however, seen in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) but is not associated with changes in HDL cholesterol, sympathetic tone, or blood pressure.10

The SRY of the Y chromosome, while necessary for testicular development, also affects expression of tyrosine hydroxylase, a rate-limiting step in the conversion of tyrosine to dihydrophenylalanine (DOPA), required for synthesis of norepinephrine, the adrenergic neurotransmitter. Translocation of this gene from a male hypertensive rat to a normotensive rat or to an autosome of a female animal results in development of spontaneous hypertension in the recipient animal.12,13

Studies need to analyze data by sex

Sex as a biological variable is dichotomous. Therefore, results from experimental and clinical studies should be analyzed by sex, as well as using sex as a covariate. This requirement for scientific excellence is not yet a reality, since the sex of cultured cells or isolated tissues used to define molecular mechanisms of disease is usually not identified or considered.

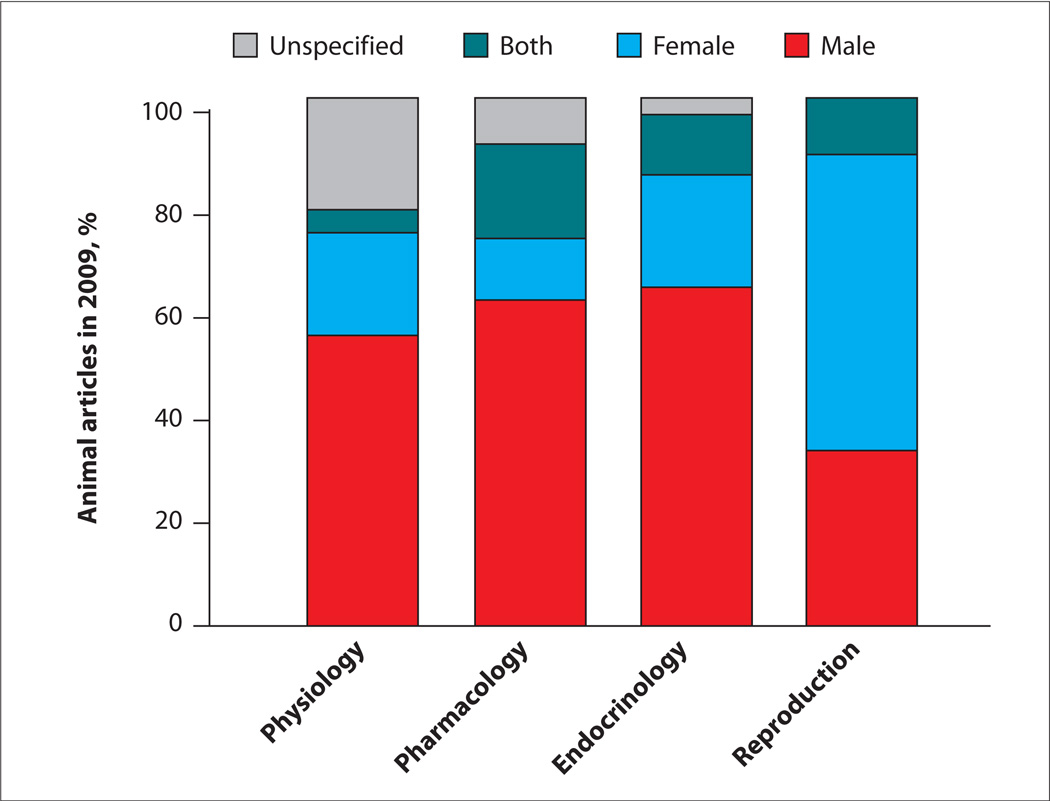

Basic and preclinical studies conducted on experimental animals in fields of study directly relevant to cardiovascular disease (physiology, pharmacology, and endocrinology) mostly use male animals (FIGURE 1).14 In clinical trials, women are underrepresented (TABLE 1).15,16 Further, position papers on diagnostic/treatment modalities or their implementation often do not consider sex.17

FIGURE 1. Most animals used in cardiovascular disease research in 2009 were male.

The chart displays the percentage of use of male, female, both male and female, or unspecified animals in basic science studies in physiology, pharmacology, endocrinology, and reproduction.

Adapted from Beery AK, Zucker I.14

TABLE 1.

Representation of women in randomized clinical trials of therapeutics used to treat cardiovascular disease

| Class of therapeutic agents | No. of trials | Overall population | % women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker | 30 | 234,028 | 30.8 |

| Antiplatelet for secondary prevention of coronary artery disease | 21 | 97,893 | 27.8 |

| β blocker | 25 | 84,930 | 35.6 |

| Lipid-lowering agents, statins | 18 | 73,693 | 26.9 |

Data from Kim AK, et al.15

Treatment efficacy in women vs men

Despite these shortcomings, many treatment modalities identified from major clinical studies may apply to women, but with some exceptions.3 For example, smoking cessation reduces the risk of myocardial infarction in women and men; however, because sex differences exist in the factors contributing to addictive behaviors and substance abuse, smoking cessation programs are best when tailored to the individual.18

Statin therapies reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and global cardiovascular risk in women as in men, but the absolute benefit in women who do not have established coronary disease is small.19 Women with established coronary disease, however, benefit as much from statin therapy as, if not more than, men.20–22

Low-dose aspirin, a standard primary prevention therapy against myocardial infarction in men, is not effective in women and is not recommended in this group until after 65 years of age.23 In both men and women, aspirin is beneficial in patients who have established coronary artery disease.

Reducing blood pressure to target levels (<140/90 mm Hg and <130/80 mm Hg in those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease) decreases cardiovascular risk in women and men.24 The impact of prehypertension on cardiovascular risk may be less in women than men.25 Medications for blood pressure control should be individualized; agents such as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors may be the treatment of choice if a woman has diabetes or heart failure, but their use should be carefully considered in any woman who may become pregnant because of risk to the fetus.

For detailed treatment strategies based on classifications and levels of evidence for women, the interested reader is referred to the latest Effectiveness-based Guidelines for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women, published by the American Heart Association.3

Sex hormones and vascular function

Although sex chromosomes provide a genetic basis for sex differences in cardiovascular disease, sex hormones represent modulating factors for genes that have response elements for the steroid receptors on both autosomes and sex chromosomes.

Transcription of these genes is differentially expressed over the life span as the endogenous concentrations of sex steroids change with sexual maturity, reproductive health, pregnancy, and aging to reproductive senescence. Influences of sex steroids on gene expression affect every organ26; however, only some studies of cardiovascular disease examine gene expression accounting for sex or reproductive/hormonal status of the study subjects.27,28

Sex steroid hormones affect all components of the vascular wall and heart: innervation, neurotransmission, extracellular matrix, smooth muscle/myocardium, endothelium/endocardium, as well as blood elements that contact the luminal surfaces (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2.

Effects of sex steroids on factors regulating vascular tone

| Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenergic neurotransmission | |||

| Synthesis of NE | Tyrosine hydroxylase | SRY ↑ | Estrogen ↑ |

| Tryosinase | Estrogen ↓ | ||

| Uptake of NE | Estrogen ↑ | ||

| Degradation of NE by COMT | Estrogen ↓ | ||

| Endothelium-derived NO | Testosterone ↑↓ | Estrogen ↑ | |

| Testosterone ↓ | |||

| Platelet secretome* | |||

| Thromboxane | Testosterone ↑ | ? | |

| PDGF | ? | Estrogen ↓ | |

Data obtained from porcine platelets, see Miller VM, et al.35

COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; NE, norepinephrine; NO, nitric oxide; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; ↑, increase; ↓, decrease; ?, not known.

Estrogen regulates adrenergic neurotransmission

Our earlier discussion on genetics mentioned how adrenergic neurotransmission is affected by the SRY gene on the Y chromosome. However, estrogen upregulates expression of tyrosine hydroxylase, as well as transporters, for uptake of norepinephrine into the nerve terminal and vascular smooth muscle. In addition, estrogen and its metabolites, the catecholestrogens, down-regulate other enzymes, including tyrosinase (required for the synthesis of tyrosine) and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) (required for the degradation of norepinephrine).8

These numerous sites where estrogen could affect adrenergic neurotransmission may in part explain the predominance of vasospastic disorders in women compared with men, the absence of a linear relationship between sympathetic nerve activity and total peripheral resistance in women,29 and changes in sympathetic tone that influence heart rate variability in women as they age.30

Perhaps the most studied effect of sex steroids on the vascular wall is estrogenic modulation of nitric oxide in endothelial cells, mediated partly by activation of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα).31 Endothelium-derived nitric oxide is considered protective against development of vascular disease. In a man lacking ERα, atherosclerosis was accelerated, and flow-mediated and endothelium-dependent vasodilatation (reactive hyperemia) was absent.31 Polymorphisms in ERα are also associated with myocardial ischemia and myocardial infarction, both of which develop as a result of endothelial dysfunction and decreased production of endothelium-derived nitric oxide.32,33

Alternatively, exogenous administration of estrogen to men undergoing transgender procedures increases reactive hyperemia. In postmenopausal women, estrogenic treatments increase reactive hyperemia, while testosterone treatments in women undergoing transgender procedures reduce it.34 Sex steroids also affect production of other endothelium-derived factors, including endothelin-1, prostacyclin, thromboxane, ACE, and reactive oxygen species.34 It is the net effect of sex steroid on synergistic and antagonistic pathways in endothelial or smooth muscle cell or cardiac myocytes that influences expression of a particular phenotype.

Hormonal influences on platelets

Blood elements, including platelets, contain receptors for sex steroids. Estrogen and testosterone affect protein content of platelets in the circulation through transcription of genes in bone marrow megakaryocytes, from which the platelets are derived. As platelets turn over (in humans, within about 10 days), changes in circulating hormone levels will affect the characteristics of the pool of circulating platelets.

As might be expected, platelets from estrogen/testosterone-replete animals will have different sensitivity to stimuli that trigger aggregation and contain different concentrations of mitogenic and vasoactive substances than platelets from gonadectomized or aged reproductively senescent animals. For example, the thromboxane content in platelets from reproductively competent male pigs is greater than that in females. Alternatively, aggregability of platelets and their content of the mitogen platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) increase with ovariectomy in female pigs; these effects are reversed by estrogenic treatments.35

These observations need validation in humans. Since platelets are implicated in vasospasticity and vascular remodeling of atherosclerosis, it is likely that these hormonal effects on platelets and their interaction with the vascular wall contribute to sex differences in expression and development of vascular disease.

Cardiovascular considerations in reproductive medicine

Information presented above supports the hypothesis that changes in concentrations of endogenous sex steroids have vascular consequences. In humans, changes in sex steroids occur throughout life—in puberty, pregnancy, menopause, and gonadal failure— and when exogenous hormonal supplements/treatments are administered.

Decreased estrogen levels raise cardiovascular risk

In the clinical setting, endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular risk increase in women as endogenous estrogen declines due to premature ovarian failure, oophorectomy, or menopause. Observational and epidemiologic studies provide convincing evidence that administration of estrogen-based therapy reduces both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality associated with these conditions in women.36–38 Randomized controlled clinical trials, however, have not validated the cardiovascular protective effects of estrogenic treatments by reducing such adverse events as myocardial infarction and stroke in postmenopausal women.39

One potential explanation for this discrepancy is the timing at which estrogen treatment is initiated. Occlusive vascular disease occurs on a continuum throughout life. Early intervention with estrogenic treatments in women who have premature ovarian failure, oophorectomy prior to age 50, and menopausal symptoms in the early postmenopause would reduce progression of disease.40 Indeed, carotid intima medial thickness (CIMT) and coronary artery calcification are reduced in menopausal women who use estrogenic treatment (including women asymptomatic for menopausal symptoms).41,42

These observations provide the basis for the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS; www.keepstudy.org). KEEPS, which will close in 2012, is evaluating CIMT and coronary artery calcification in women who were less than 3 years past menopause at study entry. Patients were randomized to 4 years of treatment with placebo (oral and transdermal), oral conjugated equine estrogen, or transdermal 17β-estradiol with pulsed micronized progesterone (12 days per month). This study is unique in that it compares oral and transdermal estrogen formulations. Transdermal delivery modalities may carry lower thrombotic risk than oral estrogen products.43

PCOS: A harbinger of cardiovascular risk

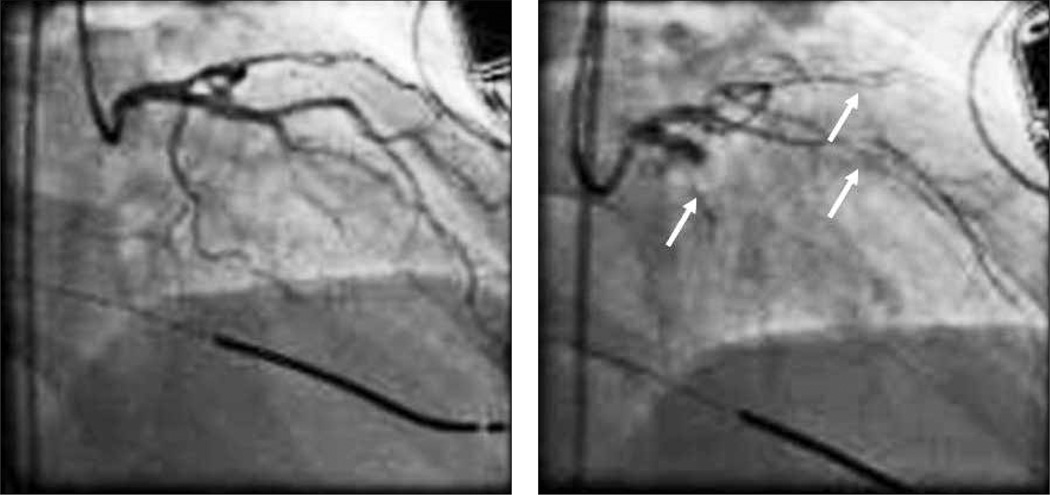

The most common endocrine disorder affecting women (approximately 4% to 10%) is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is associated with one of the earliest forms of coronary artery disease, endothelial dysfunction (FIGURE 2),44 and with a 7-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction.45

FIGURE 2.

Angiogram of a 42-year-old woman with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) prior to (left panel) and after (right panel) an intracoronary infusion of acetylcholine to evaluate endothelial function. Infusion of acetylcholine resulted in marked constriction of the coronary vasculature (arrows), indicating endothelial dysfunction, an early sign of cardiovascular disease. With healthy endothelium, vasodilatation would be expected.

Long-term treatment with estrogen and progestogen therapy to restore the estrogenic state has been shown to decrease the progression of hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and abdominal fat deposition associated with PCOS.46 Treatment of PCOS patients with either metformin or thiazolidinediones improved endothelial function.47,48 Women with PCOS often have a cluster of other cardiovascular risk factors, such as central adiposity, hypertension, and diabetes. Thus, cardiovascular prevention in this high-risk population must focus on all risk factors.

Low testosterone in men

Although some clinical evidence indicates that low testosterone in men raises cardiovascular risk, it is less clear if treatment to increase testosterone is cardioprotective.49,50 Studies of hormone treatment in men may be confounded by lack of assessment of integrity of the androgen receptors, aromatization of testosterone to estrogen, and assessment of functional estrogen receptors. Similar to studies of estrogenic treatment in women, adverse cardiovascular effects in men may be related to the timing of initiation of testosterone therapy. A study of testosterone treatment in older men (average age, 74 years) found that testosterone therapy increased the hazard ratio for adverse cardiovascular events to 5.4.51

Where do we go from here?

Much needs to be learned about the mechanisms by which sex affects development of cardiovascular disease. Effects of sex and treatment outcomes could be clarified by consistent analysis of clinical trial data by sex. Post hoc analysis of published clinical trials may reveal patterns of response and efficacy that will increase our overall knowledge of potential sex differences in various treatments. Accounting for sex as a covariate may not provide the same insight as analysis by sex as a dichotomous variable.

In addition, many questions remain about how hormonal therapies affect cardiovascular health. For example, what is the optimal timing for initiating therapy in conditions of hormonal deficiency, and what treatment duration will maximize benefits while minimizing harm? In women, based on breast cancer outcomes of the Women’s Health Initiative and the Million Women Study, it is recommended that hormone treatment be used for menopausal symptoms at the lowest dose for the shortest duration of time.52 This duration, however, may not be long enough to impact progression of cardiovascular disease, which may require from 6 to 8 years for benefit to be seen.53,54

The potential beneficial cardiovascular effects of various formulations of hormonal treatments need to be clarified. Metabolism of sex steroids is complex. Polymorphisms in genes encoding enzymes involved in these pathways have the potential to reduce treatment efficacy. For example, genetic polymorphisms in 17β hydroxydehydrogenase are associated with menopausal vasomotor symptoms, and those of catechol-O-methyltransferase may affect development of ischemic heart disease.34 Tailoring treatment modalities to genetic profiles is a goal of personalized pharmacogenomics.

Synthetic progestogens have varying degrees of efficacy for binding to glucocorticoid receptors, and some may antagonize estrogen’s effects on the cardiovascular system. Cardiovascular outcome in women using various formulations of contraceptive products, evaluated as cumulative years of exposure, is unclear at this time.55 Alternatively, the impact of fertility treatments on long-term cardiovascular risk remains to be assessed.

Conventional risk assessment tools, such as the Framingham Risk Score and Reynold’s Score, underestimate cardiovascular risk in women. Hypertensive complications of pregnancy may increase risk for cardiovascular disease in women as they age; the latest guidelines for prevention of cardiovascular disease in women include using a history of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or pregnancy-induced hypertension as part of the criteria for risk of cardiovascular disease.3 A validated assessment tool specific for women, which includes information about pregnancy, reproductive history, and hormone exposure, might improve cardiovascular risk stratification for targeting early intervention in women as they age.

Many opportunities exist for reproductive endocrinologists and other women’s and men’s health physicians to partner with basic scientists to address these issues. Gynecologists and reproductive endocrinologists may be the entry point for primary care for many women. Thus, they have the opportunity to initiate cardiovascular risk reduction and preventive strategies with their patients. Physicians can help their patients develop better personal records of hormone use and reproductive history. Some of the disparity in all-cause cardiovascular mortality between women and men will be reduced by increased understanding of how hormonal and reproductive health impact development and risk for cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Dr Miller is president of the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences and serves on the Board of Directors for the Society of Women’s Health Research. Her research is funded by a grant from the Aurora Foundation to Kronos Longevity Research Institute and grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL90636, AG29624, NS66147, and HD65987).

Footnotes

Dr Best reports no commercial or financial relationships from any sources.

Contributor Information

Virginia M. Miller, Departments of Surgery, Physiology and Biomedical Engineering, Mayo Clinic Rochester, Minnesota.

Patricia J. M. Best, Departments of Internal Medicine and Cardiovascular Diseases, Women’s Heart Clinic, Mayo Clinic Rochester, Minnesota.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon VR, Hai T, Williams SK, et al. Scientific Report Series: Understanding the Biology of Sex Differences. Washington, DC: Society for Women’s Health Research; 2005. National Institutes of Health: intramural and extramural support for research on sex differences, 2000–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. American Heart Association. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women—2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(11):1243–1262. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820faaf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wizemann TM, Pardue ML, editors. Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg RJ, O’Donnell C, Yarzebski J, et al. Sex differences in symptom presentation associated with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Am Heart J. 1998;136(2):189–195. doi: 10.1053/hj.1998.v136.88874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berookhim BM, Bar-Chama N. Medical implications of erectile dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95(1):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garovic VD, Bailey KR, Boerwinkle E, et al. Hypertension in pregnancy as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease later in life. J Hypertens. 2010;28(4):826–833. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335c29a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart EC, Charkoudian N, Miller VM. Sex, hormones and neuroeffector mechanisms. Acta Physiol (Oxf) doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02192.x. [published online ahead of print September 27, 2010]. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010 .02192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bairey Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Reis SE, et al. WISE Investigators. Insights from the NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study: Part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(3 suppl):S21–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller VM. Sex-based differences in vascular funciton. Women’s Health (London Engl) 2010;6(5):737–752. doi: 10.2217/whe.10.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van PL, Bakalov VK, Zinn AR, Bondy CA. Maternal X chromosome, visceral adiposity, and lipid profile. JAMA. 2006;295(12):1373–1374. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ely D, Milsted A, Bertram J, et al. Sry delivery to the adrenal medulla increases blood pressure and adrenal medullary tyrosine hydroxylase of normotensive WKY rats. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2007;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold AP, Chen X. What does the “four core genotypes” mouse model tell us about sex differences in the brain and other tissues? Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beery AK, Zucker I. Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim AM, Tingen CM, Woodruff TK. Sex bias in trials and treatment must end. Nature. 2010;465(729):688–689. doi: 10.1038/465688a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geller SE, Koch A, Pellettieri B, Carnes M. Inclusion, analysis and reporting of sex and race/ethnicity in clinical trials: have we made progress? J Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2011;20(3):315–320. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer A, Malik M, Schmidt G, et al. Heart rate turbulence: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use: International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electro-physiology Consensus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(17):1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Croghan IT, Ebbert JO, Hurt RD, et al. Gender differences among smokers receiving interventions for tobacco dependence in a medical setting. Addict Behav. 2009;34(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. JUPITER Study Group. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe C, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(15):1495–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [erratum apppears in N Engl J Med 2006;354(16):778] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, et al. REVERSAL Investigators. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1071–1080. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis SJ, Sacks FM, Mitchell JS, et al. Effect of pravastatin on cardiovascular events in women after myocardial infarction: the cholesterol and recurrent events (CARE) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(1):140–146. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trail of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(13):1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rich-Edwards JW, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. The primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(26):1758–1766. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506293322607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, et al. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(18):1291–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang X, Schadt EE, Wang S, et al. Tissue-specific expression and regulation of sexually dimorphic genes in mice. Genome Res. 2006;16(8):995–1004. doi: 10.1101/gr.5217506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isensee J, Witt H, Pregla R, et al. Sexually dimorphic gene expression in the heart of mice and men. J Mol Med. 2008;86(1):61–74. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0240-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heid IM, Jackson AU, Randall JC, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 13 new loci associated with waist-hip ratio and reveals sexual dimorphism in the genetic basis of fat distribution. Nat Genet. 2010;42(11):949–960. doi: 10.1038/ng.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart EC, Charkoudian N, Wallin BG, et al. Sex differences in sympathetic neural-hemodynamic balance: implications for human blood pressure regulation. Hypertension. 2009;53(3):571–576. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.126391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu CC, Kuo TB, Yang CC. Effects of estrogen on gender-related autonomic differences in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285(5):H2188–H2193. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00256.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duckles SP, Miller VM. Hormonal modulation of endothelial NO production. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459(6):841–851. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0797-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuit SC, Oei HH, Witteman JC, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2004;291(24):2969–2977. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollak A, Rokach A, Blumenfeld A, et al. Association of oestrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphism with the angiographic extent of coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(3):240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller VM, Duckles SP. Vascular actions of estrogens: functional implications. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60(2):210–241. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller VM, Jayachandran M, Owen WG. Aging, oestrogen, platelets and thrombotic risk. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34(8):814–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalantaridou SN, Naka KK, Bechlioulis A, et al. Premature ovarian failure, endothelial dysfunction and estrogen-progestogen replacement. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17(3):101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shuster LT, Gostout BS, Grossardt BR, Rocca WA. Prophylactic oophorectomy in premenopausal women and long-term health. Menopause Int. 2008;14(3):111–116. doi: 10.1258/mi.2008.008016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shuster LT, Rhodes DJ, Gostout BS, et al. Premature menopause or early menopause: Long-term health consequences. Maturitas. 2010;65(2):161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller VM, Black DM, Brinton EA, et al. Using basic science to design a clinical trial: baseline characteristics of women enrolled in the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2009;2(3):228–239. doi: 10.1007/s12265-009-9104-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarkson TB. Estrogen effects on arteries vary with stage of reproductive life and extent of subclinical atherosclerosis progression. Menopause. 2007;14(3 pt 1):373–384. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31803c764d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and cardiovascular disease in perspective. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51(3):564–580. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318181de86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manson J, Allison M, Rossouw JE, et al. Estrogen therapy and coronary-artery calcification. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(25):2591–2602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Canonico M, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G, et al. Estrogen and Thromoembolism Risk (ESTHER) Study Group. Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women: impact of the route of estrogen administration and progestogens: the ESTHER study. Circulation. 2007;115(7):840–845. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paradisi G, Steinberg HO, Hempfling A, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2001;103(10):1410–1415. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.10.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dahlgren E, Johansson S, Lindstedt G, et al. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome wedge resected in 1956 to 1965: a long-term follow-up focusing on natural history and circulating hormones. Fertil Steril. 1992;57(3):505–513. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54892-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pasquali R, Gambineri A, Anconetani B, et al. The natural history of the metabolic syndrome in young women with the polycystic ovary syndrome and the effect of long-term oestrogen-progestagen treatment. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999;50(4):517–527. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paradisi G, Steinberg HO, Shepard MK, et al. Troglitazone therapy improves endothelial function to near normal levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(2):576–580. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agarwal N, Rice SP, Bolusani H, et al. Metformin reduces arterial stiffness and improves endothelial function in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):722–730. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu PY, Death AK, Handelsman DJ. Androgens and cardiovascular disease. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(3):313–340. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phillips GB. Is atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease an endocrinological disorder? The estrogen-androgen paradox. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(5):2708–2711. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):109–122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, et al. Endocrine Society. Postmenopausal hormone therapy: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(7) suppl 1:s1–s66. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toh S, Hernández-Diaz S, Logan R, et al. Coronary heart disease in postmenopausal recipients of estrogen plus progestin therapy: does the increased risk ever disappear? Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):211–217. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-4-201002160-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harman SM, Vittinghoff E, Brinton EA, et al. Timing and duration of menopausal hormone treatment may affect cardiovascular outcomes. Am J Med. 2011;124(3):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnston JM, Colvin A, Johnson BD, et al. Comparison of SWAN and WISE menopausal status classification algorithms. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15(10):1184–1194. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]