Abstract

Building on the experiences of librarian representatives to curriculum committees in the colleges of dentistry, medicine, and nursing, the Health Science Center Libraries (HSCL) Strategic Plan recommended the formation of a Library Liaison Work Group to create a formal Library Liaison Program to serve the six Health Science Center (HSC) colleges and several affiliated centers and institutes. The work group's charge was to define the purpose and scope of the program, identify models of best practice, and recommend activities for liaisons. The work group gathered background information, performed an environmental scan, and developed a philosophy statement, a program of liaison activities focusing on seven |primary areas, and a forum for liaison communication. Hallmarks of the plan included intensive subject specialization (beyond collection development), extensive communication with users, and personal information services. Specialization was expected to promote competence, communication, confidence, comfort, and customization. Development of the program required close coordination with other strategic plan implementation teams, including teams for collection development, education, and marketing. This paper discusses the HSCL's planning process and the resulting Library Liaison Program. Although focusing on an academic health center, the planning process and liaison model may be applied to any library serving diverse, subject-specific user populations.

INTRODUCTION

The University of Florida (UF) Health Science Center Libraries (HSCL) are the primary information centers for the faculty, students, staff, and administrators of the six colleges (dentistry, health professions, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and veterinary medicine) of the Health Science Center (HSC). Thirteen librarians and fifty-nine other staff serve more than 11,000 HSC clients from three locations: Gainesville's main HSC Library and Veterinary Medicine Reading Room (VMRR) and the Borland branch library on the Jacksonville urban campus [1].

In September of 1996, the HSCL embarked on a strategic-planning process intended to position the library as a leader in the provision of health sciences information and services. A major component of the plan, completed in July of 1997, was the recommendation to develop and implement a formal Library Liaison Program [2]. In January of 1998, the Library Liaison Work Group was appointed by the HSCL director and given the following charges:

to define the purpose and scope of a library liaison program to serve the six colleges and programs of the Health Science Center;

to define the scope of library liaison activities;

to identify models of best practice for library liaisons within the field of librarianship, including in academic medical centers;

to recommend which liaison activities are essential, preferred, and desired;

to identify groups or patrons for liaison activities that have not been assigned and recommend a plan for supporting those programs.

The work group consisted of Gainesville library staff from various departments and at various levels (see authors). In May of 1998, program development was completed, and, following staff and division head's approval, full implementation was begun at the Gainesville campus in the spring of 1999.

LIAISON ACTIVITIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA HEALTH SCIENCE CENTER LIBRARIES (HSCL) AND ELSEWHERE

Library liaisons assigned to academic colleges, departments, or units (CDUs) have been shown to be effective at facilitating communication with library users and improving library services [3–9]. Liaisons can enhance the image of the library and promote new and current services to a library's users. Liaison services, in which one liaison is assigned to a particular academic unit or group of subject-related patrons, can provide focused, subject-specific customized services. By working closely with a particular group of clients, librarians can increase their understanding of user needs and facilitate responses to those needs in a more user-centered fashion. A liaison can encourage partnerships with faculty through collection development, course-integrated instruction, curriculum development, and other activities.

The HSCL already had a history of using liaisons in certain focused instances. In 1993–94, the library's Curriculum Committee, consisting of teaching librarians, discussed the use of library liaisons to colleges and developed three objectives for these liaisons:

to integrate the technological changes in information access into course work to ensure students and faculty have the skills to function in a managed-care environment;

to heighten faculty awareness of library resources and library faculty teaching expertise;

to establish a mechanism for gathering and disseminating information to support health science center college curricula [10].

HSCL librarian participation on college curriculum committees began in 1992 in the college of medicine and in 1996 in dentistry and nursing. Work on these committees reported by Francis and Fisher included performance of literature searches to support the curriculum, identification of modes of bibliographic instruction for individual classes, integration of library skills instruction into academic classes, assignment design to reinforce library skills, instruction to keep faculty abreast of the new technologies, acquisition of new materials needed by the college curriculum committee, collection and dissemination of requests for grant proposals, and consulting services [11]. The authors noted that benefits of librarian participation on college curriculum committees included increased “visibility of the library and credibility of the staff.” Francis and Fisher's work in conjunction with that of the HSCL Curriculum Committee, became the basis for “pre-program” liaison services to the HSC. These pre-program liaison relationships were extended to the remaining colleges (health professions, pharmacy and veterinary medicine) during 1997.

FORMAL PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT

Work group meetings began in January of 1998 and were scheduled for one-and-one-half hours approximately every other week. As with the strategic planning process as a whole, all members of the work group were encouraged to participate fully, without regard to rank in the organization. Minutes taken at each meeting were distributed via email to all library staff, archived on the HSCL intranet, and served several purposes: they provided a record and a reminder to help the work group keep track of the completed tasks; updated the nine other implementation groups and standing committees of work group progress, thus avoiding overlap and redundancy; and reminded the library staff at large that progress was being made—the strategic plan was not “sitting on the shelf.”

The first phase of program development consisted of information gathering and an environmental scan. It was essential that the work group identify what peer institutions were offering their patrons in terms of liaison services and develop an understanding of the current activities of the HSCL's pre-program liaisons. It was also essential that the work group scan the environment at the HSC to learn as much about users' needs as possible and to identify activities or trends in the six colleges or elsewhere on campus that might affect liaison services. Thus the information-gathering stage consisted of three primary parts: best practices, HSCL informal liaison activities, and the HSC environment.

Best practices

One work group member conducted a thorough literature search on library liaisons and identified several articles that helped to codify best practices. Another member's Internet search yielded an even greater wealth of information. Library Web pages—especially those from Kent State University [12], the University of Connecticut [13], and Dartmouth Biomedical Libraries [14]—provided details of their liaison programs that had not been found in the literature. Finally, the work group invited the members of various library email discussion lists (AAHSL-L, MEDLIB-L, SLA-DPHM, BSDNET-L) to participate in a series of short surveys to share what their libraries provided concerning liaison services (Appendix A). Information collected from these sources emphasized the ability to increase communication with and improve services to users via liaison programs.

One of the hallmarks of the literature was the utility of subject specialization by liaisons. Pratt described [15] the development, implementation, and evaluation of a biotechnology library liaison program. He noted that “For the liaison, growth in subject knowledge has been key in the evolution from providing access to literature toward identifying information” [16]. Ryans et al. described successful liaison services in an academic library and suggested that “ideally, to provide these services, the library liaison should have a strong background in the subject area of the academic unit they serve” [17]. Grover and Hale, while not specifically referring to library liaisons, discussed the role of librarians in the faculty research process [18]. They indicated that, for librarians to be truly useful to researchers, and to be part of the researchers' “visible” college, librarians needed to “be able to anticipate the researcher's patterns” [19] and be able to “identify the leading paradigms in a discipline and relate them to campus researchers and their work” [20]. They noted that “Librarians and researchers must form partnerships in order to facilitate the research process,” and “librarians who are familiar with the leading paradigms within disciplines can work more effectively with faculty researchers” [21]. What better way is there to raise awareness than through liaison subject specialization and concentration and advocacy for a particular finite domain-related group of patrons?

HSCL informal liaison activities

As noted above, pre-program liaisons had been assigned to the six HSC colleges by 1997. Additionally, two of the colleges (medicine and veterinary medicine) were assigned two liaisons each, one for clinical departments and one for basic science departments, to take advantage of librarian expertise and enhance customization of services. As part of the work group information-gathering process, all pre-program liaisons were queried via email concerning their liaison activities, plans for the future, and successes and failures thus far (Appendix B). Responses were compiled and arranged loosely under categories found on the University of Connecticut Website [22]. This list was later fashioned into a first draft of the program activities list (Appendix C) discussed below.

The email responses from pre-program liaisons gave the work group insights into the diversity of needs of the particular colleges, as well as their colleges' different levels of ability and willingness to work with liaisons. For example, the faculty from one college were unable to communicate with the library email system. Another college refused to allow a librarian access to its email distribution lists; email had to be sent to one college administrator to be passed along. A third college, although very interested in having library orientations for its doctoral students, would not relinquish time in the curriculum to have these sessions. It became clear that prescribed liaison activities would need to be kept to a minimum in the final plan and that great flexibility would be necessary. It also became clear that creativity, political savvy, and diplomacy would be requirements for service as a liaison.

HSC environment

During strategic planning, the steering committee met with deans and associate deans from the six colleges to assess user needs and expectations and to determine what new programs the colleges might be considering. Discovering these new programs and subsequently sharing the information with the work group was essential for two reasons: information concerning new opportunities was channeled to the appropriate liaison, and the information allowed the work group to introduce into the plan activities that had not yet been considered (i.e., liaison services to respond to needs of distance-education programs, liaisons' collection development to support new programs, the need for liaisons to become competent in a new subject area). HSC college and departmental Web pages were also consulted for information about CDUs and their programs.

Finally, the HSC supports a number of research centers and institutes. Some of these centers are quite specific in nature (i.e., Gene Therapy Center), while others are multidisciplinary and draw researchers from both the HSC and the main campus. It was important for the work group to determine which of these groups were affiliated with the HSC and were, therefore, HSC primary clientele. The survey to pre-program liaisons identified seventeen groups on and off campus that might benefit from liaison services (Appendix B, question 3) and served as the basis for a final list of more than forty centers and institutes related to the HSC. These centers and institutes were profiled concerning their purpose, structure, and constituency.

The information uncovered through these three avenues (best practices, HSCL informal liaison activities, HSC environment)—along with the library's goals of customized, specialized, personal service for users—were discussed and analyzed at subsequent work group meetings. The resultant Library Liaison Program consisted of three parts: library liaison philosophy statement, liaison activities, and liaison forum.

LIBRARY LIAISON PROGRAM

Philosophy statement

The first product of the work group was a philosophy statement describing the purpose of the program. The philosophy addressed the overall desired outcome and vision from the library's strategic plan.

The Health Science Center Library (HSCL) has instituted a Library Liaison Program to facilitate a partnership between the library and the Health Science Center (HSC) Colleges to support learning, research and clinical care. The program provides a range of mechanisms to enhance communications between the HSC Colleges and the HSCL, and within the HSCL. In addition to fostering coordinated communication, the program strives to support continuous improvement of library services to the colleges, strengthen the learning experiences of faculty, staff, and students, and nurture collaborative activities involving all HSCL staff.

The philosophy emphasizes inclusiveness to all primary clientele (students, faculty, staff, and administrators) of all HSC programs. All levels of HSCL staff are considered essential to the success of the program, whether they are formal liaisons or not. Communication and partnerships between library and faculty are also emphasized. Support for the mission of the colleges drives the work of the library, as well as that of the program.

Library liaison activities

The HSCL Strategic Plan clearly indicated that liaison activities would be broad and would cover a variety of areas within the library. The strategic plan had no fewer than twelve instances where the need for a liaison program was stated in recommendations [23] contributed by three of the six task forces: user education, collection development, and outreach. Specific liaison recommendations from the strategic plan included emphasizing information literacy, gathering information from users, communicating to colleges, working with curriculum development and course-integrated instruction, developing and maintaining collections, and increasing collaboration and partnerships with faculty. It became apparent that the liaison program could become the unifying theme for developing and providing library services and communication. Four other implementation groups launched from the strategic plan had some overlap in mission and membership with the work group: user education (2 members overlapped), marketing (1), HSCL internal communication (1), and collection management advisory committee (1).

Given the discussion of specialization and partnering presented in the literature, the work group envisioned a model whereby specialization combined with personal service to a CDU could facilitate the development of the five Cs: competence, customization, confidence, comfort, and communication. Specialization in this model referred both to subject expertise as well as to concentrated knowledge of the needs, trends, and politics of the assigned CDU. Limiting liaisons' duties to particular subject areas should concentrate the liaisons' efforts to develop proficiency in a specific group of resources, databases, and CDU trends and programs. It was proposed that competence gained through this specialization would enhance confidence, both of liaisons in themselves and of library users in their liaison. Increased confidence would enable the user-liaison relationship to be more comfortable and facilitate communication. Finally, this increased communication would facilitate needs assessment; understanding user needs in combination with subject expertise would allow for developing and providing personalized, customized user services. Good “word-of-mouth” communication among users based on successful interactions should increase liaison contact with users.

Seven focus areas, fashioned from the University of Connecticut list [24] and the pre-program liaison survey (Appendix B), have been identified for all library liaisons: communication, collection development, education, user services, information access, liaison development, and program evaluation. Possible liaison activities for each of these focus areas are presented in Appendix C. These focus areas are not considered a supervisor's checklist to evaluate the liaisons' activities or performance, but instead as guidelines to provide structure to the program without insisting all liaisons be identical. The activities are general enough to apply to all HSC CDUs and yet specific enough to provide some structure and consistency among liaisons. Although these are goals that liaisons should strive to meet, liaison success in each depends not only on the liaison's efforts but also on the varying needs of the CDUs, the acceptance of liaisons into the CDU, and the CDUs' abilities to deal with the liaisons.

Communication (Focus Area 1)

This focus area refers to communication from liaison to CDU, CDU to liaison, and liaison to liaison. As bridges to their users, it is essential that liaisons communicate frequently with patrons, keeping them abreast of changes in library policy, new databases and services, and whatever specialized information is important to the CDUs. Joining email distribution lists, attending departmental meetings, and participating on college curriculum committees are some ways communication to these groups occurs.

However, communication must not be a one-way street. Liaisons must make use of their patron base to gain information, whether via conducting formal needs assessment, sending periodic mass emails for help in collection development, or just by making their users feel comfortable enough that unsolicited comments, suggestions, and questions are sent to the liaisons. Liaisons should be considered the users' primary contact at the library. Users should not have to identify and remember one contact to request items be ordered for the library, another to ask for help with electronic resources, and yet another to get detailed subject-specific reference services. The liaison can provide “one-stop shopping,” either by solving the request or by referring the question internally to the appropriate specialist. Liaisons are advocates for both the library and the CDUs, so a high comfort level must be developed between the liaisons and their CDUs. Some modes of information gathering about CDUs can be quite unobtrusive. For example, a liaison may be placed on departmental newsletter mailing lists to gain information about journal clubs, research priorities, departmental policies, plans, publications, and so forth. Being added to departmental seminar mailing lists and keeping track of the dissertations coming out of departments can give insights into research collection needs.

The third component of communication is among liaisons. Communication regarding activities of the various CDUs, and what activities have worked well or have not worked and why, can keep liaisons from unproductive duplication of effort. Although liaisons are expected to use their professional judgment to disseminate information informally and in a timely manner to other liaisons and appropriate library management, formal means of communication have also been developed (see “Library liaison forum” below). For everyday communication needs, an email discussion list has been developed for the HSCL liaisons, and minutes of the liaison forum meetings are archived on the library intranet.

It is also essential that internal and external communications be consistent and accurate. Although uniformity of information is important, it must be balanced by the individual needs, politics, personalities, and modes of communication of the various CDUs. For major changes in library resources or policies, it makes sense for one person familiar with the details to draft a message that the liaisons can customize for their users.

Collection development (Focus Area 2)

During the development of the program, the HSCL standing Collection Management Advisory Committee was also developing its formal Collection Development Policy, including goals and guidelines for selectors of materials. The suggested liaison activities for collection development support the developed guidelines.

Collection development builds on Focus Area 1, communication. All liaisons are expected to understand their CDUs' missions, curricular offerings, clinical requirements, and research interests to build viable collections to support these efforts. Catalogs, course descriptions, reserve readings, course syllabi, faculty publications, academic department seminars, planned future course curricula, participation on CDU committees, and informal surveys of faculty all provide indications of collection need. Furthermore, communication from liaisons to the CDU regarding budget constraints or surpluses, new product trials, and acquisition of materials in relevant areas of teaching or research is key. Additionally, collaboration among other campus libraries and overlap between collections are areas for consideration and opportunities for liaison input.

Continuous successful collection development depends upon liaisons improving subject expertise in their CDUs' disciplines over time. This expertise may not be consistent among liaisons; some liaisons are degreed subject experts, while others acquire knowledge on the job via continuing-education coursework, core bibliographies, and memberships in professional organizations. Liaison development (Focus Area 6) plays an important role here.

Liaisons are expected to evaluate the collection in their subject domains and identify areas where coverage is inadequate or outdated. Circulation statistics and user surveys can suggest needs. Liaisons evaluate and recommend electronic and print resources that support their CDUs. Liaisons must understand how their CDUs will use the various resources and their expectations of these resources. Reevaluation of the collection must be continuous to ensure the collection is adequately meeting the needs of the CDUs and does not stagnate.

The bottom line for collection development is that no two liaisons or CDUs will have the same needs or solutions. Each subject discipline is vastly different. Some have better-developed collections than others and will require less effort by the liaison. Other CDU subject areas are dramatically underdeveloped and will need much effort by the liaisons to bring the collection up to a minimum standard. In turn, budget allocations can vary each year and will affect the speed with which a collection is enhanced.

Education (Focus Area 3)

During the development of the program, the HSCL also developed its formal education plan through its Education Work Group, an extension of its Strategic Planning User Education Task Force. Although details of the new HSCL Education Plan will be reserved for another forum, liaison emphasis in education should clearly parallel the education plan. The plan emphasizes partnering with academic faculty to develop course-integrated instruction (rather than simple library orientations); creating courses for academic faculty development; customizing classes to specific user needs and types of user (faculty, students, researchers, clinicians); advertising this customization; enabling liaisons to specialize in teaching; using liaisons as conduits for developing students' lifelong learning skills; and increasing the library's bioinformatics instruction. Many ideas in both the education plan and liaison program were based on past HSCL successes and failures.

User services (Focus Area 4)

This focus area is broad in scope, covering provision of multiple services by the library to the HSC as a whole. The liaisons play marketing and public relations roles in communicating to the CDUs the availability of the library's services and, in turn, communicating to the library the CDUs' special needs. The library can then work as a partner with the CDUs in achieving their goals. To accomplish this partnership, liaisons must be knowledgeable about the CDUs' programs to identify their needs and about library services and resources to fulfill needs.

For example, the HSCL provides as a standard service a computer lab and adjoining classroom where access to electronic databases, word-processing and spreadsheet software, Internet and email is provided to all faculty, staff, and students of the HSC. In contrast, a special need of a CDU may be to use the computer classroom as a test-taking site for a semester. Liaisons play an important function in communicating to the CDUs the availability of the library's services and, in turn, communicating to the library the CDUs' special needs. Other user services that liaisons could provide in this area include email communications to the CDUs when library services are changed or enhanced, conducting user-needs assessments so new services could be developed that directly support unmet needs, tailoring faculty packets to each CDU emphasizing the services that would be of special benefit to them, offering individualized support for reference queries, and orienting faculty.

Information access (Focus Area 5)

In this area, the liaisons serve to identify and provide access to resources in any format that support the CDUs' missions. Again, communication plays a major role. Liaisons must communicate to the CDUs the addition of new resources in the library, the availability of resources on a trial basis, and the resources that would most appropriately suit the CDUs' research or teaching needs. In turn, liaisons must solicit input from the CDUs regarding the types of information access that are most desired and best suited to their discipline and environment.

For example, polling the faculty of the college of pharmacy led to changing a subscription to an electronic database. The poll indicated that the current database was not meeting the needs of the college sufficiently. This indication led to the trial and purchase of another resource that better suited the activities of the college's students, faculty, and staff.

Another activity liaisons undertake to promote access to information is the development of subject-specific Web pages. Previous to the development of the Library Liaison Plan, two HSCL librarians created SearchNet [25], a subject guide to Internet-based resources in the health sciences available through the HSCL Website. This resource has now evolved into the HSCL's Internet Resource Catalog (IRC) [26]. With the liaison program in place, the liaisons work with the Web manager to populate this IRC with evaluated Websites and assist in subject classification. Liaisons may also arrange links back and forth to CDU Internet resources.

Liaison development (Focus Area 6)

This focus area is crucial to the success of the program. Subject specialization by liaisons enhances their competence and improves the quality of their services (collection development, database searching, user training, in-depth reference) and customers' confidence in the liaisons. The demonstrated quality of service and the ability to communicate in the specialty “lingo” develops the customers' confidence in their liaisons.

Although the HSCL is fortunate to employ liaisons with advanced degrees in biology, psychology, and public health, liaisons are not required to have acquired subject knowledge through academic programs or advanced degrees. Without the subject background, however, liaison expertise development is essential, time consuming, and expensive.

For liaisons to specialize competently, they need to take the initiative to learn the subject areas. Pratt has suggested [27] multiple ways to develop biotechnology liaison subject expertise including auditing doctoral level courses, extensive database and vendor training, and attendance at local biotechnology presentations and at Medical Library Association continuing-education (CE) classes in biotechnology. In cases where subject expertise did not already exist, Ryans et al. have stressed the need for “more support, such as subject bibliographies from the collection development office, release time to attend classes in the subject area, and clerical help” [28]. Other ways librarians may become competent in the subject area include sitting in on or taking classes through their assigned CDUs, reading CDU newsletters, attending their departmental seminars, and reviewing dissertations written by students in their CDUs. Joining the appropriate organizations (e.g., sections or special interest groups of the Medical Library Association, divisions of the Special Libraries Association, and discipline-specific groups like the library section of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy) is also useful.

Even when liaisons have a good understanding of a subject area, they must continue to learn specifics, new trends, and vocabularies and to learn how the subject areas relate to their CDUs. Just as the program emphasizes lifelong learning for the library patrons, the program must emphasize lifelong learning for the liaisons; growth and development should be continuous. The library must support the liaisons in these endeavors with time and funding.

Program evaluation (Focus Area 7)

The seventh focus area is also essential to the success of the program. Evaluation will not only assess how well the program is working: its results will be used to help fine-tune the program each year to make it even more effective. Liaisons will write annual reports for each of their liaison assignments, describing activities, successes, challenges, changes in their CDUs, and future plans. A survey, following Yang [29], will be performed to determine users' perceptions of the program.

Francis and Fisher [30] have enumerated necessary competencies for librarians serving on college curriculum committees. These librarians must be able to provide bibliographic instruction, exhibit excellent database- and Internet-searching skills, possess knowledge of databases and library services, and be familiar with various teaching techniques and multiple educational theories. They have also noted that library liaisons should “have excellent interpersonal skills, be able to listen and synthesize information, be able to make tactful suggestions, recognize opportunity, and promote library services which can be incorporated into the curriculum.” These characteristics, in addition to subject expertise, are required for the liaisons in the HSCL program as well. Throughout implementation of the program, liaisons will meet to identify and discuss the other attributes that facilitate liaison success. These “knowledge, skills and abilities” will not be a supervisor's checklist, but, like the liaison activities, will serve as guidelines and goals to which liaisons should aspire.

Library liaison forum

Following the example of the University of Connecticut [31], the work group created the liaison forum to provide formal communication for all liaisons. The purpose of the forum was to provide an opportunity for all the liaisons to meet to plan activities for the coming semester; share ideas, concerns, successes, and problems; and collaborate on activities as appropriate, including:

identifying needed services;

identifying new resources, services, and policies information needing dissemination;

sharing information about CDUs with other liaisons;

reviewing proposed library policies or changes for impact on colleges;

sharing ideas that work and ideas that do not work;

assessing annual goals; and

evaluating the program.

The work group recommends that meetings occur monthly for at least the first year and no less than three times a year once the program is well underway. A yearly retreat is recommended to deal with long-range planning and policy adjustment. Agenda-coordinating and minute-taking responsibilities are assigned on a yearly basis. Participation in the forum would include all officially appointed liaisons, along with invited representatives from the circulation, interlibrary loan, collection management, resource management, marketing, and library administration departments. The opening of the forum to staff other than the liaisons facilitates communication among the library staff of changes in library services, library and CDU news, and other important information. It also allows liaisons to express concerns about the impact of library policy and service changes and allows for the development of uniform messages from the HSCL to users.

In planning the liaison forum, the work group recognized the value of liaisons and other staff learning from each other about what works and does not work and about the political and cultural realities of the CDUs. The struggle for the work group was to find a timely yet effective approach to sharing information and experiences.

Program approval

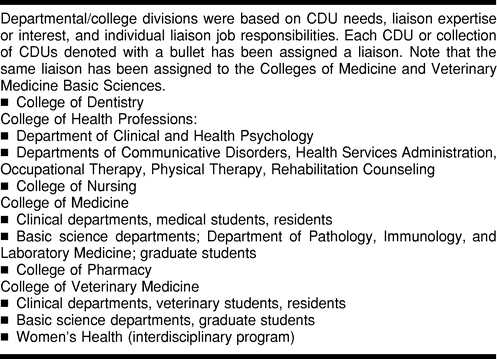

The HSCL's first official liaison forum was held on July 30, 1998. At this meeting, the program was presented to pre-program liaison librarians. The plan was accepted by the liaisons with minor word changes to the philosophy and activities list. During this session, liaisons also described their activities and plans and preparations for the upcoming fall semester. Most of the discussion centered around course-integrated instruction, communication activities, and marketing of services. The program was then sent to division heads, the library's senior management team, for final ratification. Once sanctioned, liaisons were encouraged to use the list of activities to expand their services and to market these services to their users. Final formal liaison assignments (Table 1) were made and implementation was ready to commence in the fall of 1998. Staffing shortages delayed implementation, and the formal program effectively started during the spring semester of 1999.

Table 1 Formal library liaison appointments to HSC colleges, departments, and units (CDUs) at commencement of Library Liaison Program implementation

FUTURE EVALUATION AND ISSUES TO CONSIDER

Formal evaluation of the program will begin in the spring of 2001, giving liaisons sufficient time to query their users concerning information needs, initiate a variety of activities, and market the activities to their clientele. Indirect and direct measures will follow those described in the “Program evaluation” section. Even prior to formal program evaluation, several issues, which may necessitate fine-tuning the program, have come to the forefront.

Covering large colleges, departments, or units (CDUs)

Questions remain concerning the appointment of liaisons to large colleges, those with hundreds of faculty, staff, and students. The HSC's College of Medicine (COM) is the largest CDU, with more than 950 faculty and 500 students. This college is covered by two liaisons (one for clinical and one for research areas) based on the liaisons' expertise and interests. However, this split is uneven—the clinical liaison covers sixteen clinical departments, medical students, and residents, while the research liaison covers seven basic science departments, one clinical department, graduate students, and post-doctoral students. The clinical assignment may prove to be too large for one liaison and may necessitate the assignment of a third liaison to the COM.

Covering diverse CDUs

Some colleges are also quite diverse. The College of Health Professions (COHP) covers six marginally related departments (clinical and health psychology, communicative disorders, health services administration, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and rehabilitation counseling, with health informatics joining the fold sometime in 2000–01). At the beginning of implementation, two liaisons were assigned to the COHP. One liaison covered clinical and health psychology, as she had subject expertise and had been working with this department for many years, building close relationships with her users. A second librarian was named the formal liaison to the remaining five departments, necessitating expertise in widely divergent subject areas. Covering so many disparate departments may not be practical for one person.

Overlapping subject area among liaisons

Some subject areas are included in two or more unrelated CDUs and are addressed by more than one liaison. For example, the COM includes a Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, which is covered by the COM research liaison. The College of Pharmacy (COP) naturally has its own interest in pharmacology and related topics and is covered by the COP liaison. Dentistry, nursing, and veterinary medicine also have interests in these areas and are covered by separate liaisons. It is essential that these liaisons communicate effectively and coordinate planning. Good communication cannot be mandated by the program; instead liaisons must be willing to share turf and learn from each other.

Departing or replacing liaisons

This issue was first discussed through the email discussion list questionnaire during the initial information-gathering stage of program development (Appendix A). The work group did not resolve the issues of liaison recruitment in the event of a liaison's departure or how to foster backups for liaisons. Searching for new staff members based on a specific liaison opening might limit the pool of applicants dramatically. Shifting assignments to accommodate a new librarian's interest or expertise would result in loss of subject skills and relationships developed by the staff member changing CDUs. How should backups be assigned to cover short-term departures (vacations, attendance at association meetings, illness)? This area will be addressed during the early phases of program implementation.

Covering branch locations

The initial program is meant to cover the needs of the main HSCL and will be implemented there first. The Borland Library and the Veterinary Medicine Reading Room have unique needs and serve unique sets of users. Although the program is designed to be flexible and give the liaisons broad range in serving their CDUs, the program may need to be adjusted to ensure that the needs of the branch locations are adequately addressed. Does the Jacksonville campus need its own formal liaison located at Borland, or does current HSCL liaison communication with Borland users suffice? Does a librarian need to be onsite at the VMRR? How do the College of Veterinary Medicine liaisons fit into this issue? As the program progresses and gaps in service become more apparent, additional liaison appointments may be necessary.

Extending liaison services to other groups

As noted above, pre-program liaisons suggested seventeen additional on- and off-campus groups that would benefit from liaison services, and the work group identified and analyzed more than forty HSC-affiliated institutes and centers that did not have formal liaison assignments. For a variety of reasons, the work group determined that no official liaison relationship would be extended to these groups during the first year of program implementation. Although workload issues were a consideration, additional factors affected the decision. Nearly all faculty, students, and staff of the HSC institutes and centers have liaison coverage through their home departments. Non-HSC UF groups, although heavy users of the HSCL, are officially covered by other libraries on campus. Thus, the work group determined that forming formal liaison ties to these groups would be impolitic; instead, an informal communication network will be developed. Finally, given the staffing situation at the library and workload issues, non-UF groups are being considered for services on a case-by-case basis but are not receiving formal liaison coverage. These issues will be revisited following the first year of program implementation.

Monitoring workload

The majority of the liaison activities (collection development, teaching, database searching, etc.) involved in the program are those expected of all reference librarians hired at the HSCL and, theoretically, would not increase the librarians' workloads. Subject specialization, in fact, may be expected in some ways to reduce workload (i.e., the more competent librarians are in their specific areas of expertise, the more quickly they can accomplish specific tasks; librarians will do less work outside their areas of expertise). As the program will be heavily marketed to users, the work group expects that liaisons will perform more searches, teach more classes, answer more questions via email, and have more formal consultations with users. Additionally, liaisons will be much more involved in needs assessment for their particular CDUs, a task that had not been a primary responsibility of pre-program liaisons. It is essential to document how these new responsibilities affect workload. Liaisons will keep detailed statistics and present them in their annual reports. The HSCL's non-liaison librarians (professionals other than those in public services) are not expected to see their workload affected by the program.

CONCLUSIONS

The HSCL's Library Liaison Program has been developed to improve services to library users. Hallmarks of the program include subject specialization, intensive communication with users, and personal, customized services. The program provides a framework for liaisons through its philosophy and seven focus areas for activities. It also facilitates communication and learning among the liaisons through the liaison forum. Although formal evaluation of the program has not yet occurred, there is consensus among liaison librarians that the program is valuable and has facilitated improved services to the HSCL's users. Liaisons have indicated that communication with users is at an all-time high. Preliminary evidence suggests that the CDUs are intrigued by and are accepting the Library Liaison Program. Faculty and students are apparently using their liaisons as their primary contact point in the library.

The program has provided the groundwork and infrastructure from which to implement successful liaison services. However, the program should be viewed as a dynamic, ever-evolving entity that will need continuous assessment and fine-tuning to thrive. Difficult situations, as well as successes, must be addressed throughout program implementation. Several of these “issues to consider” have been noted above. Surely, more issues will become apparent during continuing program implementation. HSCL liaisons and staff are looking forward to completing implementation and performing the 2001 program evaluation to test expectations and to provide direction for future program enhancement.

APPENDIX A

Survey of existing liaison programs in academic libraries

Seventeen contact people in academic libraries with liaison programs were identified from inquiries to several Internet discussion lists (e.g., AAHSL-L, MEDLIB-L, SLA-DPHM, BSDNET-L). Each library supported programs in health professions, but not all served several distinct health-related colleges as the HSCL does. A survey of fourteen questions, divided into four topic areas, was sent out by email during a four-week period. Eleven people responded to at least one group of questions. Responses varied widely in amount of detail offered and in the practices described.

Week 1: liaison groups

How is your liaison program administered or managed?

Do you have a formal mechanism for liaisons to coordinate and communicate their activities and ideas? If so, please explain.

How often do your liaisons meet as a group? If so, what are the outcomes from those group meetings?

Would you or your library be interested in participating in a liaison email discussion list, if one were formed?

Highlights: A majority of liaison programs were associated with their library's collection development or selection functions. Most also had some forum for communicating about their liaison activities, but the format of the group and the frequency of meetings varied widely. A few expressed interest in a liaison program email discussion list, but none was developed at that time.

Week 2: assignment of responsibility

What process do you use to assign liaison responsibilities?

When a staff member leaves, what process do you use to reassign their liaison responsibility?

When a position with liaison responsibility is vacant, do you include liaison responsibility in the position advertisement?

Do you require subject expertise in the liaison area?

Highlights: Most liaison assignments were based on a combination of interest and academic background or expertise. Vacancies often meant an opportunity for reshuffling, but some were just filled by the new person. Position ads usually included liaison responsibilities, but rarely mentioned a specific subject area. Expertise was valued when available, but interest and willingness to learn were also important factors.

Week 3: sharing liaison responsibility

For large colleges, like the college of medicine, do you assign more than one person to provide liaison activities?

If a college or department has more than one liaison, how are the liaison activities shared or divided?

If selection is a responsibility of the liaison, how is it assigned for large colleges, like the college of medicine?

Highlights: Some libraries had divided their colleges of medicine, with each liaison assigned several departments. There was often a relationship to selection responsibilities as well as an effort to balance workload.

Week 4: liaison development and evaluation

What are the skills and abilities you desire in a successful liaison?

What training have you identified to assist staff in improving their liaison skills?

How do you evaluate whether a liaison is successful?

Highlights: There was great consensus on the importance of communication skills. Also mentioned were service orientation and teaching skills. Formal coursework, training-the-trainer sessions (especially for teaching computer-based resources), inhouse training, and continuing-education classes were all means of developing greater expertise. Increases in the awareness of and use of library resources by the client group and indications that they were using their liaisons as conduits were seen as evidence of success.

APPENDIX B

Survey of HSCL “pre-program” liaison activities

Nine HSCL librarians responded to the following questions concerning their informal pre-program liaison activities. Summaries are presented below each question.

Question 1: For each group to which you are a liaison, please list for us what you currently do. Annotate your answers as necessary

Summary: All nine pre-program liaisons indicated that they had provided some user-directed services. Thirty total activities were listed, varying in specificity and depth. Several liaisons had performed course-integrated instruction or library orientation and collection development. Some liaisons had access to or developed their own email distribution lists for communication with faculty, attended college curriculum committee meetings, contributed to curriculum development, performed literature reviews for faculty, and joined affiliated groups to promote liaison self-development. Twenty-three additional activities were reported by no more than one liaison each.

Question 2: For each group to which you are a liaison, please list your plans for the future

Summary: Eight of the nine liaisons responded, listing twenty-eight different activities they planned for the future. The most common responses included: extending course-integrated instruction for returning students, performing needs assessment for their CDUs, developing workshops for faculty, and offering more stand-alone database classes customized for their CDUs. Several liaisons described how they planned to increase communication with their users and learn more about their CDUs, including developing faculty and student email distribution lists, meeting with department chairs, attending department meetings to describe the liaison program, creating a “dog and pony show” describing the program, orienting new CDU faculty to the library, attending CDU seminars, and perusing CDU Web pages. Liaisons noted they would attend continuing-education classes to improve their subject knowledge and planned to add subject-specific areas to SearchNet [32].

Question 3: Are there groups on or off campus that you feel you (or another liaison) should be covering, but are not currently covered?

Summary: Five liaisons suggested a total of seventeen programs that would benefit from HSCL liaison services, including HSC CDUs (e.g., Brain Institute and Cancer Center), non-HSC University of Florida groups (e.g., departments of zoology and health and human performance), and off campus non-UF groups (e.g., nurses in Gainesville and the Florida AIDS Education and Training Center). “Issues to Consider” contains a discussion of liaison services to these groups.

Question 4: From your experience, what has worked well, or not so well, in your liaison activities so far?

Summary: All three liaisons who served on college curriculum committees indicated that this participation had been fruitful, resulting in new contacts. Academic faculty became more aware of librarians' abilities and contributions and more comfortable and collegial toward them. One liaison reported that participating in email distribution lists and learning about CDUs through unobtrusive means (CDU newsletters, Web pages, seminars, dissertations, and other research documents) had been quite effective.

Liaisons reported experiencing challenges as well. Scheduling meetings with busy faculty members was problematic. One liaison cited lack of time to devote to liaison services. Some liaisons noted that they had not yet been able to reach many people, and one of the more established liaisons indicated that she could not determine how to make her users “more proactive” in using liaison services. Another liaison noted that she probably needed to be “more aggressive” in marketing to her users.

Question 5: Any advice, suggestions, specific directions you would like our work group to discuss?

Summary: Pre-program liaisons did not provide the work group with much help in this category. Respondents recommended that liaisons be proactive and suggested that increased latitude and independence of the liaison would result in better response from the CDUs. One liaison offered the use of some training materials on how to interview faculty about their research information needs.

APPENDIX C

Focus areas and liaison activities

The HSCL's Library Liaison Program (LLP) unifies seven focus areas: communication, collection development, education, user services, information access, liaison development, and program evaluation. Potential activities for each focus area are listed below.

1. Communication

1.1 Make regular contact with the assigned college, department, or unit (CDU; i.e., institute, center, program, etc.).

1.2 Consult within the HSCL to ensure that the information communicated to the CDU is accurate and timely.

1.3 Inform the CDU's faculty, staff, and students of new library policies and procedures.

1.4 Inform the CDU's faculty, staff, and students of new library resources and services.

1.5 Provide information about available library services and resources to the appropriate CDU as new programs are established in those areas.

1.6 Advise HSC faculty on course-integrated instruction development.

1.7 Consult with faculty, staff, and students about appropriate purchases for the library's collection.

1.8 Solicit and encourage ongoing HSC faculty input regarding their activities, interests, or programs and their information and education needs.

1.9 Support collaborative relationships between the HSCL and the HSC CDUs.

1.10 Be an advocate of the CDU, so they have their interests represented to the HSCL.

1.11 Be an advocate for the HSCL, so that its resources, services, and needs are represented to the CDU.

1.12 Participate in a forum of all HSCL liaisons to share ideas to enhance the LLP.

2. Collection development

2.1 Develop and maintain comprehensive knowledge of the information resources pertinent to the CDU.

2.2 Represent the CDU's interest in implementing the collection development policy of the HSCL.

2.3 Evaluate and select appropriate materials in the key subject areas of the CDU.

2.4 Solicit and encourage ongoing HSC faculty, staff, and student input regarding new items for the collection regardless of format.

2.5 Monitor and evaluate the acquisition process.

2.6 Notify faculty about new library materials of interest to their research or teaching.

2.7 Evaluate subject coverage and ensure that the CDU's subject areas are current and adequately represented in the collection to meet the information needs of faculty, staff, and students.

2.8 Evaluate the HSCL's resources in support of new CDU programs.

2.9 Evaluate the special needs of the CDU concerning age of materials; weed or retain as appropriate.

2.10 Collaborate with other UF campus libraries to coordinate purchase of resources.

3. Education

3.1 Monitor CDU activities or programs relevant to the development of educational programs by participating on a curriculum committee, attending departmental meetings, or through other less formal means.

3.2 Develop educational sessions and syllabi that will aid faculty, staff, and students in acquiring information literacy and critical thinking skills.

3.3 Develop and coordinate bibliographic instruction for all faculty, staff, and students in the CDU, whether course-integrated instruction, faculty development sessions, staff workshops, or in-office consultations.

3.4 Support and encourage the use of course-integrated instruction in CDU's curriculum.

3.5 Consult with faculty about the design of assignments to involve the use of library resources.

3.6 Communicate to the HSC faculty, staff, and students information about relevant instructional sessions offered by the library or by a library liaison to another CDU.

3.7 Support the use of new learning techniques and technologies in the CDU's curriculum.

3.8 Provide support for distance-education programs that are part of the CDU's program.

3.9 Evaluate and identify the need for guides to library resources in the subject disciplines of the CDU. Develop appropriate guides based on those identified needs.

3.10 Coordinate with other liaisons about guides of general interest to all library users.

3.11 Collaborate with other University of Florida campus libraries to coordinate the provision of library educational sessions.

4. User services

4.1 Ensure that faculty, staff, and students of each CDU are aware of ongoing library services and resources.

4.2 Inform the CDU of new or revised library services available to them.

4.3 Provide information about available library services and resources to the appropriate CDU as new programs are established in those areas.

4.4 Support development of appropriate guides to library services.

4.5 Offer individualized support for subject-specific reference needs to college faculty, staff, and students when requested.

5. Information access

5.1 Select appropriate electronic resources to support the CDU.

5.2 Solicit and encourage ongoing HSC faculty input regarding the availability of new electronic resources in their subject discipline.

5.3 Inform the faculty, staff, and students of the CDU of new electronic resources relevant to their subject discipline.

5.4 Advise the faculty, staff, and students about the most appropriate electronic resources for their research needs and how to access those resources.

5.5 Compile subject-related Internet resources for the CDU.

6. Liaison development

6.1 Participate in a forum of all HSCL liaisons to share ideas to enhance the LLP.

6.2 Develop subject knowledge in the disciplines that make up the assigned CDU.

6.3 Participate in subject-related divisions, interest groups, or sections of professional library organizations relating to liaison activities and attend meetings as appropriate.

6.4 Develop knowledge of the professional organizations and their resources related to the disciplines within the CDU.

6.5 Participate in relevant organizations (whether local, state, regional, national, etc.) in the CDU's subject discipline and attend meetings when appropriate.

6.6 Participate in training opportunities to enhance skills as liaisons.

7. Liaison program evaluation

7.1 Solicit feedback from the HSC Colleges regarding the LLP, its achievements and areas for improvement.

7.2 Provide an annual report of the activities, successes, program strengths, and barriers and suggested areas for improvement as liaison to their CDU.

7.3 Utilize feedback and annual reports to update LLP.

Footnotes

* Based on a poster presented at the Forty-eighth Annual Meeting of the Southern Chapter of the Medical Library Association, Lexington, Kentucky, October 12, 1998.

REFERENCES

- University of Florida Health Science Center Libraries. 1998–1999 annual report. Gainesville, FL. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- University of Florida Health Science Center Libraries. Strategic plan [Web document]. Gainesville, FL: The University, 1998. [cited 18 Apr 2000]. 〈http://www.library.health.ufl.edu/about/sp.htm〉. [Google Scholar]

- Francis BW, Fisher CC. Librarians as liaisons to college curriculum committees. Med Ref Serv Q. 1997 Summer; 16(0):69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt GF. Liaison services for a remotely located biotechnology research center. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Oct; 79(0):394–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryans CC, Suresh RS, Zhang WP.. Assessing an academic library liaison programme. Libr Rev. 1995;44(0):14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schloman BF, Lilly RS, and Hu W. Targeting liaison activities: use of a faculty survey in an academic research library. RQ. 1989 Summer; 28(0):496–505. [Google Scholar]

- Shedlock J. The library liaison program: building bridges with our users. Med Ref Serv Q. 1983 Spring; 2(0):61–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Bowman M, Gardner J, Sewell RG, and Wilson MC. Effective liaison relationships in an academic library. Coll Res Libr News. 1994 May; 55(0):254–303. [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZY. University faculty's perception of a library liaison program: a case study. J Acad Librarianship. 2000 Mar; 26(0):124–8. [Google Scholar]

- Francis BW, Fisher CC. Librarians as liaisons to college curriculum committees. Med Ref Serv Q. 1997 Summer; 16(0):70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis BW, Fisher CC. Librarians as liaisons to college curriculum committees. Med Ref Serv Q. 1997 Summer; 16(0):70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent State University. Liaison program directory [Web document]. Kent, OH: The University, 1996. [cited 3 Oct 1996]. <http://www.library.kent.edu/collection/lpdirect.html>. (Note: this URL is no longer active.). [Google Scholar]

- University of Connecticut Libraries. Academic liaison program [Web document]. Storrs, CT: The University, 1998. [cited 9 Jan 1998]. 〈http://spirit.lib.uconn.edu/liaison/〉. [Google Scholar]

- Dartmouth College Library, Biomedical Libraries. Library liaison program [Web document]. Hanover, NH: The University, 1997. [cited 18 Dec 1997]. 〈http://www.dartmouth.edu/∼biomed/services.htmld/liaison. htmld〉. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt GF. Liaison services for a remotely located biotechnology research center. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Oct; 79(0):394–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt GF. Liaison services for a remotely located biotechnology research center. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Oct; 79(0):400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryans CC, Suresh RS, Zhang WP.. Assessing an academic library liaison programme. Libr Rev. 1995;44(0):21. [Google Scholar]

- Grover RJ, Hale ML. The role of librarians in faculty research. Coll Res Libr. 1988 Jan; 49(0):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Grover RJ, Hale ML. The role of librarians in faculty research. Coll Res Libr. 1988 Jan; 49(0):12. [Google Scholar]

- Grover RJ, Hale ML. The role of librarians in faculty research. Coll Res Libr. 1988 Jan; 49(0):11. [Google Scholar]

- Grover RJ, Hale ML. The role of librarians in faculty research. Coll Res Libr. 1988 Jan; 49(0):13. [Google Scholar]

- University of Connecticut Libraries. Academic liaison program [Web document]. Storrs, CT: The University, 1998. [cited 9 Jan 1998]. 〈http://spirit.lib.uconn.edu/liaison/〉. [Google Scholar]

- University of Florida Health Science Center Libraries. Strategic plan [Web document]. Gainesville, FL: The University, 1998. [cited 18 Apr 2000]. 〈http://www.library.health.ufl.edu/about/sp.htm〉. [Google Scholar]

- University of Connecticut Libraries. Academic liaison program [Web document]. Storrs, CT: The University, 1998. [cited 9 Jan 1998]. 〈http://spirit.lib.uconn.edu/liaison/〉. [Google Scholar]

- Flint SE, Hsu PP. Internet for ready reference: hypertext reference sources. Poster Session, Southern Chapter of the Medical Library Association Annual Meeting, Memphis, TN, October 14, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- University of Florida Health Science Center Libraries. Internet resource catalog [Web document]. Gainesville, FL: The University, 1999. [cited 18 Apr 2000]. 〈http://www.library.health.ufl.edu/irc/Catalog/〉. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt GF. Liaison services for a remotely located biotechnology research center. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Oct; 79(0):394–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryans CC, Suresh RS, Zhang WP.. Assessing an academic library liaison programme. Libr Rev. 1995;44(0):22. [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZY. University faculty's perception of a library liaison program: a case study. J Acad Librarianship. 2000 Mar; 26(0):124–8. [Google Scholar]

- Francis BW, Fisher CC. Librarians as liaisons to college curriculum committees. Med Ref Serv Q. 1997 Summer; 16(0):73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Connecticut Libraries. Academic liaison program [Web document]. Storrs, CT: The University, 1998. [cited 9 Jan 1998]. 〈http://spirit.lib.uconn.edu/liaison/〉. [Google Scholar]

- Flint SE, Hsu PP. Internet for ready reference: hypertext reference sources. Poster Session, Southern Chapter of the Medical Library Association Annual Meeting, Memphis, TN, October 14, 1996 [Google Scholar]