Abstract

This study explored the drug resistance strategies that urban American Indian adolescents consider the best and worst ways to respond to offers of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana. Focus group data were collected from 11 female and 9 male American Indian adolescents attending urban middle schools in the southwest. The youth were presented with hypothetical substance offer scenarios and alternative ways of responding, based on real-life narratives of similar youth. They were asked to choose a preferred strategy, one that would work every time, and a rejected strategy, one they would never use. Using eco-developmental theory, patterns in the preferred and rejected strategies were analyzed to identify culturally specific and socially competent ways of resisting substance offers. The youth preferred strategies that included passive, non-verbal strategies like pretending to use the substance, as well as assertive strategies like destroying the substance. The strategies they rejected were mostly socially non-competent ones like accepting the substance or responding angrily. Patterns of preferred and rejected strategies varied depending on whether the offer came from a family member or non-relative. These patterns have suggestive implications for designing more effective prevention programs for the growing yet under-served urban American Indian youth population.

Substance abuse and its associated health problems have long been recognized as major factors in health disparities experienced by American Indian communities (Dixon, 2001; Indian Health Service, 2001, 2005, 2009). Research on ways to improve addiction prevention, treatment, and aftercare for American Indians is an urgent priority of American Indian community leaders, urban Indian coalitions, and health providers (Association of American Indian Physicians, 2005; Joseph-Fox & Kekahbah, 1999; National Urban Indian Family Coalition, 2008). Although comprehensive and coordinated approaches across the lifespan are needed to prevent or postpone the initiation of substance use and reduce its harmful effects on health, there is a critical need for substance abuse prevention programs for American Indian youth that address their unique cultural and social environments, recognizing important differences among those from urban areas rather than reservation communities and among those from different tribes and regions (May & Moran, 1995; Moran & Reaman, 2002).

The current study focused on an essential component for developing effective prevention interventions for urban American Indian youth: knowledge of culturally and developmentally appropriate ways to successfully resist substance use. Based on findings from focus groups where these youth prioritized different ways of responding in situations where alcohol and drugs might be offered or available to them, the study sought to identify and assess the preferred drug resistance strategies of urban American Indian youth in a large southwestern city. The study relied on the youths as expert informants, and analyzed their responses from an eco-developmental perspective (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999) that situated substance use scenarios within the social and developmental contexts of their daily experience (Okamoto, LeCroy, Dustman, Hohmann-Marriott, & Kulis 2004). The analysis leads to several provisional conclusions about the culturally determined nature of vulnerability and resistance to substance use offers and opportunities for urban American Indian youth. These conclusions have suggestive implications for the design of prevention programs for this growing yet underserved American Indian population.

SUBSTANCE USE AMONG AMERICAN INDIAN YOUTH: PREVALENCE AND HEALTH CONSEQUENCES

American Indians suffer disproportionately from preventable diseases that result from substance use (Centers for Disease Control, 2006). Age-adjusted mortality rates attributable to alcohol dependence are six or more times higher for American Indians and Alaska Natives than for non-Hispanic Whites (Indian Health Service, 2009). Of the 10 leading causes of death among American Indians, four are connected closely to substance abuse: liver disease and cirrhosis, injuries, suicide, and homicide (Centers for Disease Control, 2001). The corresponding rates in Arizona, the site of the current study, indicate that alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among American Indians constitutes the most extreme ethnic or racial health disparity in the state (Arizona Public Health Association, 2005; Mrela & Torres, 2008).

These disparities have roots early in the life course. Compared to non-native adolescents, American Indian youth report higher rates, earlier onset, and more severe consequences of substance abuse, and they are more likely to perceive minimal risk of harm from substance use (Moncher, Holden, & Trimble, 1990; Rutman, Park, Castor, Taualii, & Forquera, 2008; SAMHSA, 2004). By age 11 nearly one-third of American Indians have tried alcohol (Mail, 1995) and a majority have used illicit drugs by age 17 (SAMHSA, 2006). Over half of American Indian youth report having tried marijuana, rates that are higher than for other racial/ethnic groups (Indian Health Service, 2005). In addition to the high prevalence of substance use, some American Indian youth are reported as especially vulnerable to heavy or very frequent use of alcohol (SAMHSA, 2005), marijuana (Novins & Mitchell, 1998), and tobacco (Moncher et al., 1990). Disparities in mortality attributable to alcohol abuse and dependence are particularly high among the young, nearly 13 times higher among American Indian men aged 15–24 than among non-Hispanic whites of the same age (Indian Health Service, 2004).

Substance use is a major public health problem for all youth, but its consequences for American Indian youth are particularly severe. Compared with other racial/ethnic groups, American Indian youth have more damaging health, social, and economic consequences related to substance use (Schinke, Tepavac, & Cole, 2000), including depression, conduct disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidality (Stiffman, Striley, Brown, Limb, & Ostmann, 2003). Substance use has been linked to risky sexual behavior among American Indian youth (Baldwin, Maxwell, Fenaughty, Trotter, & Stevens, 2000; Fenaughty, Fisher, Cagle, Stevens, Baldwin, & Booth, 1998; Hellerstedt, Peterson-Hickey, Rhodes, & Garwick, 2006; Simoni, Sehgal, & Walters, 2004), and to increased vulnerability to academic failure, delinquency, unemployment, and violent criminal behavior (Moncher et al., 1990).

These health disparities in substance use and its consequences extend to the majority of the American Indians who now are urban residents (Castor, Forquera, Lawson, Park, Smyser, & Taualii, 2006; National Urban Indian Family Coalition, 2008; Urban Indian Health Commission, 2007), and to urban American Indian youth specifically (Rutman et al., 2008). The early onset and severe impact of substance use for urban American Indian youth create a critical need for the development of effective drug use prevention approaches for this underserved population.

AMERICAN INDIAN YOUTH SUBSTANCE USE FROM AN ECO-DEVELOPMENTAL PERSPECTIVE

The diversity of urban American Indian communities makes any generalizations difficult, but the high prevalence and severe consequences of substance abuse among urban American Indian youth is often attributed to common experiences of family and residential instability, socioeconomic stress, and cultural disruption. Urban American Indian families frequently move between the reservation and the city and experience very high mobility within the city. This residential instability, in turn, is associated with familial instability and a high proportion of low income households with a single mother or extended kin as household head (King, Smith, & Gracey, 2009). Multiple familial factors have been implicated in the vulnerability of American Indian youth to substance use, many related to unstable home environments (Garrett & Herring, 2001). These include poor child rearing practices (Herring, 1997a), lack of parental monitoring (Chewning, Douglas, Kokotailo, LaCourt, Clair, & Wilson, 2001), drug offers from family members (Kulis, Okamoto, Rayle, & Nyakoe, 2006), deficient family support or caring (Chewning et al., 2001), excessive free time (Herring, 1997b), parental and community permissive attitudes about drug use and adult modeling of substance use (Moran & Reaman, 2002; SAMHSA, 2004), low familial importance on education (Chewning et al., 2001), cultural conflicts (Garrett & Herring, 2001; Herring, 1997a, 1997b), and socioeconomic stressors (Clarke, 2002; SAMHSA, 2004). These same familial factors are cited as placing Arizona’s urban American Indian youth at unacceptably high risk for substance abuse, teen pregnancy, delinquency, school drop-out, and violent behaviors (Urban Indian Coalition of Arizona, 2009).

Other factors placing American Indian youth at risk for substance use include stress due to discrimination, forced assimilation, colonization, and loss of culture (Beauvais, 1998; Frank, Moore, & Ames, 2000; Whitbeck, Chen, Hoyt, & Adams, 2004). As has been found for immigrant and other ethnic minority youth, American Indian youth may be vulnerable to substance use as a means of coping with cultural conflicts that arise from trying to fit in the dual worlds of mainstream and native culture (LaFromboise, Trimble, & Mohatt, 1990; Schinke, Shilling, Gilchrist, Asby, & Kitajima, 1989).

Eco-developmental theory provides a framework for understanding how American Indian youths’ vulnerability to drug use is shaped by familial, community, peer, cultural, and societal forces (Coatsworth, Pantin, McBride, Briones, Kurtines, & Szapocznik, 2002; Perrino, Gonzalez-Soldevilla, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2000; Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). The theory outlines how substance use may be encouraged or discouraged through the interaction of nested systems. Microsystems are social groups in which the youth participate directly (e.g., family, school, peers). Mesosystems describe relationships between microsystems that influence the youth indirectly (e.g., parent-peer or parent-school interactions). Macrosystems are broad social forces and structures that influence the youth (e.g., culture, social inequality). Social support within and coordination among these systems facilitates positive social outcomes, while conflict among them can lead to behavior problems, such as substance use. With its primary responsibility for the socialization of youth, the family plays a pivotal role in the development or prevention of problem behaviors (Coatsworth et al., 2002).

Consistent with eco-developmental theory, studies of American Indian youth have revealed patterns of substance use risk and resiliency that emerge from interdependent relationships with peers and family members. In reservation communities, siblings and cousins—both biological and ascribed—exert strong peer pressure to engage in or resist substance use (Trotter, Rolf, & Baldwin, 1997). This influence may be magnified when American Indian youth interact with cousins in multiple environments (e.g., school and their reservations), which may compound either the risk of encountering their cousins’ substance offers or serve to intensify protection, as when cousins “look out” for each other in multiple settings (Hurdle, Okamoto, & Miles, 2003; Waller, Okamoto, Miles, & Hurdle, 2003). Although intergenerational cycles of drug abuse and parental offers of substances to their children are cited as posing serious risks for American Indian youth (Nielsen, 1994), urban American Indian youth report that offers of alcohol and drugs from cousins are more difficult to handle than offers from parents (Okamoto et al., 2004). Other studies have emphasized the influence of peer approval and of substance abusing friends and peers in the substance use trajectories of American Indian youth (Bates, Beauvais, & Trimble, 1997; Beauvais, 1992; Kegler, Kingsley, Malcoe, Cleaver, Reid, & Solomon, 1999; Sellers, Winfree, & Griffiths, 1993). The relative importance of parents versus peers or cousins, however, may vary by substance. In a study linking substance offers to actual substance use, urban American Indian youth exposed to more parental substance offers reported more frequent use of licit substances (alcohol and cigarettes), while substance offers from cousins predicted more frequent use of marijuana (Kulis et al., 2006). In addition, gender differences appear in the sources of substance offers and their connection to substance use among urban American Indian youth (Rayle, Kulis, Okamoto, Tann, LeCroy, Dustman, et al., 2006). Compared to their male counterparts, females report more substance offers from their parents, greater difficulty in resisting the offers, and a stronger association between substance offers from parents and personal use of substances. These studies document the importance of considering the sociocultural and relational context in which substance use occurs for American Indian youth, in particular variations in outcomes depending on the youths’ relationship to the person offering substances and the type of substance offered.

The eco-developmental macrosystem for American Indian youth includes the influences of sociohistorical experiences, culture, and institutions. Stressors connected to forced assimilation, colonization, and acculturation are well-identified factors in substance abuse among American Indian youth (Beauvais, 1998; Frank et al., 2000), leading to calls for prevention efforts that recognize the unique sociohistorical/cultural contexts in which these youth operate (Garrett & Herring, 2001) and their experiences of environmental, institutional, and interpersonal discrimination (Browne & Fiske, 2001; Walters, Simoni, & Evans-Campbell, 2002).

PREVENTION EFFORTS FOR URBAN AMERICAN INDIAN YOUTH

Recommendations for the development of drug abuse prevention efforts for American Indian populations have centered on ways to integrate authentic representations of distinctive features of American Indian culture. These include: the incorporation of narratives that are infused with culturally appropriate symbols, metaphors, and relationships; consciousness of nonverbal communication; recognition of essential differences in native and Western philosophies of wellness; and awareness of healing practices rooted in religious and spiritual traditions (More, 1989; Nebelkopf & Phillips, 2004). Efforts to identify practices that have cultural resonance across tribes have focused on a common holistic approach to healing that addresses spirit, mind, and body, and connects the individual to the family, community, and culture (Alvord & Van Pelt, 1999; Arguelles, Buchwald, Garroutte, Goldberg, & Sarkisian, 2006). Researchers recommend avoiding the “disease model” of substance abuse used in many prevention and treatment programs because it has less relevance to American Indians (Garrett & Carroll, 2000; Stubben, 2001).

Some prevention programs build upon core cultural values as a way to increase identification with American Indian culture, a demonstrated means of helping American Indian youth avoid risk behaviors (Moran, Fleming, Somervell, & Manson, 1999; Stubben, 2001; Whitbeck, Hoyt, McMorris, Chen, & Stubben, 2001). There are examples of successful intervention programs for American Indian youth targeting substance abuse, self-esteem, problem solving, and family cohesion that are systematically designed to strengthen connections to American Indian values (Moran et al., 1999; Stubben, 2001). Numerous substance abuse prevention efforts for American Indian populations exist and are in use, but most can be classified as culturally supported interventions (CSI) that have been developed at a grassroots level through social service programs serving native communities (Duran, Wallerstein, & Miller, 2007). These programs typically incorporate cultural values and traditions that gain the community’s trust and support, but are seldom evaluated for efficacy using scientific methods (Beauvais & Trimble, 2003; Chavez, Duran, Baker, Avila, & Wallerstein, 2003; Duran & Walters, 2004; Hawkins, Cummins, & Marlatt, 2004). However, there are relatively few evidence-based substance use prevention programs for native youth that have been subjected to rigorous scientific standards in development and testing (Marlatt, Larimer, Mail, Hawkins, Cummins, Blume, et al., 2003; Schinke et al., 2000). Programs developed specifically for urban American Indian youth are especially rare (Moran & Bussey, 2007).

Existing prevention programs designed specifically for American Indian youth have typically incorporated some version of personal and social skills training that is integrated with cultural components specific to the population, including those developed for native youth populations in the Pacific Northwest (Dorpat, 1994; Gilchrist, Schinke, Trimble, & Cvetkovich, 1987; Schinke, Orlandi, Botvin, Gilchrist, Trimble, & Locklear, 1988; Schinke et al., 1989; Trimble, 1992), Rocky Mountains (Moran, 1998), Plains states (Schinke et al., 2000), and Northeast (Schinke, 1999). A complement to prevention programs based on improving personal and social skills in general is to provide training in the use of drug resistance strategies and teaching specific skills for handling substance use offers and opportunities. This approach is founded on research showing that youth are less likely to use substances if they have a wide repertoire of drug resistance strategies and are socially adept at turning down substance offers while maintaining relationships with peers (Doi & DiLorenzo, 1993; Jackson, Henriksen, Dickinson, & Levin, 1997; Skara & Sussman, 2003). Four drug resistance strategies—refuse, explain, avoid, and leave—have been found to be used most often by U.S. adolescents and by youth in some areas of Mexico (Alberts, Miller-Rassulo, & Hecht, 1991; Hecht, Alberts, & Miller-Rassulo, 1992; Kulis, Marsiglia, Castillo, Becerra, & Nieri, 2008; Reardon, 1989). These four strategies form the basis for the drug resistance training that is a core component in the keepin’ it REAL substance use prevention program in middle schools, a model program listed on the SAMHSA National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (Hecht, Marsiglia, Elek-Fisk, Wagstaff, Kulis, & Dustman, 2003).

Prevention programs that teach a repertoire of drug refusal strategies have been found to be effective among multicultural samples including Latino and African American youth (Botvin, Schinke, Epstein, & Diaz, 1994; Hecht et al., 2003; Kulis, Marsiglia, Elek, Dustman, Wagstaff, & Hecht, 2005). However, there is some evidence that existing drug resistance training programs are less effective for American Indian youth than for other youth, possibly because these programs are insufficiently adapted to native cultural values and social settings (Dixon, Yabiku, Okamoto, Tann, Marsiglia, Kulis, et al., 2007). Cultural backgrounds can shape the social contexts in which substances are offered or available, as well as influence which responses to offers are considered acceptable or preferred (Gosin, Marsiglia, & Hecht, 2003; Hecht et al., 1992; Hecht, Ribeau, & Alberts, 1989; Marsiglia & Hecht, 2005; Moon, Hecht, Jackson, & Spellers, 1999). To date there is little systematic research on culturally appropriate drug resistance skills employed by American Indian youth, and none specifically addressing urban Indian youth. The current study attempts to address this gap.

METHODS

Prior Phases of the Study

The current analysis is the final phase of a study whose aim was to identify culturally specific factors that contribute to resilience and drug resistance among urban and semi-urban American Indian youth, and to apply the findings to inform culturally grounded prevention efforts for these youths (see Okamoto, LeCroy, Tann, Rayle, Kulis, Dustman, et al., 2006). All phases of the study utilized data provided by American Indian middle school students attending public schools in the Phoenix, Arizona metropolitan area. The first phase of the study utilized reports from 10 gender-segregated focus groups where youths were asked about the situational contexts where they encountered opportunities and pressures to use substances (see Waller et al., 2003). A content analysis conducted by multiple members of the research team, and focusing on the narrative content of the focus group transcripts (Neuendorf, 2002), extracted a list of 62 typical situations of urban or semi-urban American Indian youth encounters with substance use. The second phase of the study recruited a new sample of 71 American Indian youth from three public middle schools in the Phoenix metropolitan area who completed a self-administered questionnaire, reporting the frequency with which they encountered each of the 62 typical substance offer scenarios, and the perceived difficulty of dealing with these situations. The scenarios were widely prevalent: over half the youths had experienced at least two of the scenarios, a third had been in seven scenarios, and one-fifth had encountered 40 or more of the scenarios (see Okamoto et al., 2004).

Design of the Current Study

Informed by these prior study phases, the current study asked focus groups of urban American Indian youth to list and prioritize different ways of responding to the most common and most difficult substance offer scenarios. The procedures were designed to generate realistic and culturally specific responses to situations where native youth faced opportunities to use substances. These methods mirrored those used by MacNeil and LeCroy (1997) to identify culturally grounded and socially competent responses to challenging situations faced by youth.

Setting

The study site—the Phoenix metropolitan area—exemplifies several of the defining features of many urban American Indian communities: a long migration history, multi-tribal community identities and values, and strong ties to reservation communities (e.g., Ackerman, 1988, 1989; Bonvillain, 1989a, 1989b; Lobo, 2001; Salo, 1995). For decades Phoenix has been a migration destination for American Indians, with stages that reflect the influence of the Federal government’s past assimilationist relocation policies, emigration in search of economic and educational opportunities in the city, and the encroachment of an explosively growing non-native population that has reached the borders of Indian reservations adjacent to the city. Phoenix now has the second largest urban American Indian population, after Los Angeles (National Urban Indian Family Coalition, 2008). The U.S. Census Bureau’s 2005 American Community Survey counted 81,185 American Indian residents in the metropolitan area, not including those who identify as multi-racial or live on reservations adjacent to the metropolitan area. American Indians in Phoenix report many tribal affiliations, with the largest single tribe, the Diné/Navajo, accounting for about one-fourth. The proximity to Phoenix of the 21 American Indian nations located in Arizona allows for frequent return visits for ceremonies and family responsibilities (Guillemin, 1975; Straus, 1998; Weibel-Orlando, 1994).

Sample

The participants in this study phase were a convenience sample of urban American Indian youth in two urban public middle schools. The students were enrolled in a cultural enhancement program for native students, a program delivered during regular school hours that is sponsored and staffed by the largest multi-service agency serving the local urban Indian community. Students were eligible for this program if their parent(s) completed a Title VII form indicating their tribal affiliation when enrolling their child in school. In one school, six female students participated in the sessions where data for the current study were collected. This group stayed intact for all sessions and students collaborated as a single group. In the second school, five female and nine male students participated, and students self-selected into several small groups. The student participants at the two sites represented a wide range of tribal backgrounds, with the majority affiliated with the Diné/Navajo, Apache, or Hopi nations.

Focus Groups

The focus groups were led by adult American Indian program facilitators from the local urban Indian services agency. They were trained by the research team to guide the focus group sessions using elements of brainstorming (rules, procedures) as well as different ways to group students to foster more interaction and active participation. In the focus group sessions, the youth were presented with representative situations where urban American Indian youth like themselves had reported being offered alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and other drugs. The situations were 25 of the 62 scenarios identified in the prior phase of the study that youth had encountered most frequently and found most difficult to handle (see Okamoto et al., 2004). The research team organized the 25 scenarios into five sets, ensuring that each set represented different eco-developmental social contexts, including a range of substances (alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana), different persons offering the substances (parents, other adult family members, cousins, friends, other peers), and a variety of settings (e.g., after-school, party, home, family gathering) (see Table 1). The order of the items in the five sets of scenarios was rotated among different groups of students.

Table 1.

Substance Offer Scenarios

| Scenario Set (A–E) and Type (Offeror, Substance) | Full Scenario |

|---|---|

| A1: Parents offer beer | You’re at home with your cousin, and your mother and father are drinking beer. They offer some to both you and your cousin. |

| A2: Other adult offers liquor | Your parents take you to the bar with them and someone there offers you some liquor. |

| A3: Family offer cigarettes | Your whole family goes to celebration party and everyone takes out cigarettes to smoke, and they pass them around to everyone who doesn’t have them. |

| A4: Cousin offers marijuana | All the cousins are together and one of the older ones passes a joint of marijuana around the group, calling everyone names who doesn’t want to take a hit. |

| A5: Older peers offer liquor | You and your friends run into some older kids who are drinking. They offer you a bottle of liquor. |

| B1: Parents offer cigarettes | When you and your family attend celebrations, your brothers and sisters are smoking cigarettes. When you tell your parents, they laugh and say, “Try it, if you want to.” |

| B2: Family offers marijuana | When you’ve gone over to a family member’s house, they tell you to try some marijuana and they tell you “it’s no big deal.” |

| B3: Cousins offer liquor | At a family celebration your cousin holds out some liquor to you and keeps telling you over and over, “Take a drink, c’mon, what are you scared of? |

| B4: Peers offer marijuana | You start talking to a kid in your class and don’t know well, and after school the kid asks you if you want to stop by the park on the way home and smoke some marijuana. |

| B5: Friends offer marijuana | One night you’re out with your friends. Everyone goes out back behind your one friend’s house to smoke marijuana and get high. |

| C1: Parents offer liquor | You go home after school and your mom and dad are at home with a couple of friends and they have been drinking and are pretty messed up. They give you some liquor and say you need to learn how to hold your own. |

| C2: Aunts and uncles offer beer | You’re at a family fathering, and a bunch of your aunts, uncles, and cousins are playing a drinking game with beer. Several of your aunts and uncles invite you to play the game with them. |

| C3: Cousin offers marijuana | While walking home from school with two of your cousins, one of them asks you if you’ve ever tried marijuana. Right then, the other cousin pulls out a joint, lights it up, and offers it to you. |

| C4: Friend offers marijuana | At a friend’s house after school with several of your friends, someone passes around a joint of marijuana. The joint comes around to you. |

| C5: Peer offers liquor | Your friend and you are at the corner store with this person you both know, who is trying to find someone who will buy you a bottle of liquor. |

| D1: Family offers liquor | You are visiting some family members. They tease you about not being taught enough to make it in the world while they are handing you some liquor. |

| D2: Cousin offers marijuana | You’re over at your cousins’ house, talking and stuff. One of you cousins rolls up a joint of marijuana and hands it to your other cousin, and says if you want, you can have a hit too. |

| D3: Older peers offer beer | You’re the youngest one in a whole carload of teenagers. They begin to pass a bottle of beer around to everyone in the car, and make fun of anyone who doesn’t take a big drink. |

| D4: Peers offer liquor | You’re hanging out outside with these really cool kids, and they pass around a bottle of liquor and everyone takes a drink. |

| D5: Friends offer marijuana | Two of your friends are walking home from school with you, and one of them asks if you’ve tried marijuana. The other friend pulls out a joint, lights up, and offers it to you. |

| E1: Parents offer beer | Your parents have been drinking and says “Help yourself to a beer.” |

| E2: Aunt and uncle offer beer | At your cousin’s house, your aunt and uncle are drinking beer. They offer a bottle of beer to both you and your cousins. |

| E3: Cousins offer beer | All the cousins are together and one of them passes a bottle of beer around the group. |

| E4: Friends offer marijuana | A group of kids corner you at school and they pressure you to drink beer with them. |

| E5: Peer offers marijuana | It’s Saturday night and you’re at a party with some friends. There is a lot of music and many people of all ages are drinking and smoking. Your friend comes over to you with this person you don’t know, who offers a joint of marijuana. |

At the first sessions of the focus groups, the youth were presented with the 25 drug offer scenarios and told that these situations were ones that occur for many youth. Students were asked to think about how they would react to each situation and then brainstormed potential responses. The facilitator read each real-life scenario, then paused for students to write down one possible response before moving on to the next scenario. After the first sessions, all of the suggested responses to each particular scenario from all participants were typed up verbatim by the research team, eliminating duplicate responses to particular scenarios, but with no attempt at further coding or categorization. The responses were then printed onto a poster under a description of the specific scenario that had elicited them, creating a separate poster for each of the 25 scenarios that were presented to the students.

Two weeks after the brainstorming sessions, the students met again with the objective of evaluating and prioritizing the potential responses they had enumerated in the earlier sessions. This step of the process was focused on how the students identified socially competent ways of responding. Facilitators used the sorting process known as the Nominal Group Technique, in which students were asked to evaluate whether their brainstormed responses would be socially acceptable and useful in real life. Students were presented in turn with each of the 25 scenarios and possible responses listed on a poster board. They were asked first to select the one strategy that would “work every time.” Each student was prompted to put an adhesive dot on the poster next to their chosen strategy. Before the group moved on to the next scenario, students were then asked to select a strategy they “would never use,” and place a different colored dot next to that one. There was no prescribed order among the students for placing dots on the poster boards, and students were invited, but not required, to make known their choice of a preferred and a rejected strategy. Most did so. There were two instances where students chose not to register a preferred option by placing the dots and 15 instances where they did not select a rejected option. The prioritization process took two sessions at one school and three sessions at the other school.

Data Analysis

After the prioritization sessions, the research team calculated the number of students who selected a particular strategy as the preferred (“would work every time”) and rejected (“would never use”) response to each scenario to produce raw counts, combining information from the two school sites. Several steps of analysis ensued. First, the responses and their corresponding preferred and rejected raw counts were sorted into 14 types of strategies that emerged through a prior qualitative analysis (Kulis, Reeves, Dustman, & O’Neill, in press; see Table 2, “brainstormed”). These types had been derived by the research team, working individually and in pairs, by grouping common actions together and assigning an umbrella term or a pertinent theme for each type of responses. Intercoder reliability was ensured by rechecking and adjusting initial coding decisions, each time with additional coders involved.

Table 2.

Responses to Substance Offer Scenarios

| Strategy type | Brainstormed as potential responsea | Preferred: “Would work every time”b | Rejected: “Would never use”b | Preferred adjusted to 100%c | Rejected adjusted to 100%c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refuse—say “No” to the offer or that you do not want to use the substance | 10.5% | 11.0% (38/345) | 23.2% (80/345) | 5.9% | 15.2% |

| Explain—give a reason for resisting the offer, including a fabricated reason | 14.6% | 10.3% (39/380) | 7.1% (27/380) | 5.5% | 4.7% |

| Avoid/Evade—stay away from the situation or take an evasive action while remaining | 4.6% | 10.0% (19/190) | 4.2% (8/190) | 5.3% | 2.8% |

| Leave—leave the surroundings altogether or move away from the offeror or substance | 11.2% | 18.1% (52/287) | 8.7% (25/287) | 9.6% | 5.7% |

| Pass—pass on the offered substance to someone else | 4.4% | 13.2% (16/121) | 5.8% (7/121) | 7.0% | 3.8% |

| Pretend—create a pretense of accepting the offer without using the substance | 2.2% | 23.6% (21/89) | 2.2% (2/89) | 12.5% | 1.5% |

| Redirect—change the subject or offer a substitute activity; give an irrelevant or inane response unconnected to the offer | 7.3% | 7.7% (19/248) | 10.9% (27/248) | 4.1% | 7.1% |

| Destroy/Discard—destroy the substance, openly or discreetly; eliminate the chance for others to use it | 4.9% | 15.5% (29/187) | 6.4% (12/187) | 8.3% | 4.2% |

| Set Relationship Boundaries—question the appropriateness of the offeror’s behavior, given their relationship | 3.4% | 14.8% (20/135) | 5.9% (8/135) | 7.9% | 3.9% |

| Accept—accept the substance offered or agree to take it, including conditionally | 13.4% | 24.4% (78/320) | 30.9% (99/320) | 13.0% | 20.3% |

| Anger/Aggression—negative verbal or physical response | 1.5% | 8.5% (8/94) | 23.4% (22/94) | 4.5% | 15.4% |

| Challenge—counter offer with strong language, forceful opinions, or name calling; challenge the offeror’s status | 14.1% | 12.3% (41/333) | 22.5% (75/333) | 6.5% | 14.8% |

| Deny/Disclaim—view offer as hypothetical or counter-factual; state that (s)/he and/or other people would not use the substance | 6.8% | 8.7% (24/276) | 1.1% (3/276) | 4.6% | 0.7% |

| Distance/Reflect—assess or judge others’ substance use in a detached manner; distance oneself from them or their actions | 1.0% | 10.0% (4/40) | 0.0% (0/40) | 5.3% | 0.0% |

| Total N (responses or selections) | 410 | 408/3045 | 395/3045 | ||

| Total % | 100% | 188.1c | 152.4c | 100% | 100% |

Percentage of all strategies presented on poster boards as initially brainstormed potential responses to the 25 scenarios.

Raw count/number of times this strategy type was presented.

Percentages adjusted proportionally across all types to add to 100% (i.e., multiplying column 3 percentages by 100/188.1 and column 4 percentages by 100/152.4.

Second, the raw counts of preferred and rejected strategies were transformed into a proportional (percentage) measure of the probability of selecting a particular type of strategy, by dividing the raw count by the number of times that type of strategy could have been selected. For these calculations, the numerator was the total raw count of times a particular type of strategy was selected as preferred, or as rejected, and the denominator was the frequency that responses of that type appeared on posters multiplied by the number of students making selections for those posters. This adjustment was important because the students had brainstormed certain types of strategies more often than others as possible responses to the scenarios, and the number of distinctive responses listed varied from scenario to scenario. On the poster boards presented to the students, each scenario had between 12 and 19 distinct possible responses listed (mean = 16.4), and these responses fell into 6 to 11 of the 14 substantive types identified by the research team (mean = 7.9). Thus, for particular scenarios not all strategies were represented, and some presented the same strategy in multiple ways. For example, some version of the “explain” strategy—citing a reason for declining the substance offer—was listed as a response to 22 of the 25 scenarios, more often than for any other type of strategy. Moreover, on the posters where it did appear, the explain strategy was listed from one to six different ways; i.e., providing various explanations for declining the offer (to live longer, not die young, avoid cancer, escape addiction, stay out of juvenile detention, evade parental punishment). Other types of strategies appeared less often on the poster boards, some much less often. For example, the strategy of pretending to use the substance was listed for only 6 of the 25 scenarios, and for these it appeared in only one or two specific versions (e.g., act like you drank some, not let it in your mouth).

Without adjustments for the varying number of times that certain types of strategies appeared on the poster boards, strategies that were listed more often would automatically have higher odds of emerging as preferred strategies, and strategies listed infrequently would have artificially low odds of being selected. After the adjustments, however, the odds of selection were calculated based on a shifting denominator such that the probabilities summed to greater than 100%. Thus, a second adjustment was made, multiplying the initial calculation of the odds of selection of each type of strategy, in percentages, by a fraction that returned their sum to 100%. This preserved the rank order and relative position of the selections but made it easier to compare the tendencies to identify certain types of strategies as potential (brainstormed), preferred, and rejected options (see Table 2 footnotes).

In the third step of analysis, the probabilities of selecting particular types of strategies as preferred and rejected courses of action were further analyzed after first sorting the scenarios into subcategories according to the relationship to the person offering the substance (friends, other peers, cousins, parents, extended family).

RESULTS

Table 2 presents a breakdown by substantive type of the strategies that students brainstormed as potential responses to the scenarios, and then those they selected as the preferred (“would work every time”) and rejected (“would never use”) choices. The table provides definitions of the responses in each of 14 types, which can be sorted further into four groups:

the “REAL” strategies—refuse, explain, avoid, leave;

other relatively passive or indirect strategies—pass, pretend, redirect;

other assertive strategies—destroy/discard, set relationship boundaries;

and ineffective strategies lacking social or communication competence—accept, anger/aggression, challenge, deny/disclaim, distance/reflect.

Before describing the preferred and rejected choices we briefly summarize the broad substantive types into which they were sorted through an earlier analysis (Kulis et al., in press).

The REAL strategies included refuse, a simple response of saying no to the offer or making a clear statement that one did not want to use the substance, without providing a rationale. The explain strategy provided a reason or excuse for turning down the substance, often citing concerns about the negative effects of substance use (“I’d say I’m scared of getting cancer”), getting into trouble with parents and adult authorities (“Say you can’t because your mom knows when someone has been drinking”), and interfering obligations (“I have to babysit”). The avoid/evade responses were divided almost equally between staying away from situations where substances would be offered or available (“I wouldn’t go near them”) or remaining present but evading substance use (e.g., “drink water instead of alcohol”). The strategy of leaving included walking away from risky situations calmly or fleeing hurriedly (“I’d grab my cousin and run out”).

A second group of responses involved more passive but potentially effective ways of resisting the offer—pass, pretend, and redirect. The passing strategy usually described simply handing the substance to another person without any verbal comments, but also some instances of passing the substance back to the offeror. Pretend included a variety of ways to feign to use the substance without actually doing so, again non-verbally. Redirect strategies included even more diverse ways to shift the focus of the interaction away from the substance offer by changing the subject or making attention-getting remarks unrelated to the substance offer.

The next group of responses—destroy/discard and setting relationship boundaries—represented relatively assertive ways to resist substance offers other than the REAL strategies. Destroying or discarding the substance was offered at times as an open and even confrontational response (throwing it on the floor), but also as a less overt form of resistance, such as dropping or spilling the substance, that would prevent others from using the substance as well. Another response would be to set boundaries by questioning the nature of the offeror’s relationship to the student, stating or implying that the substance offer was inappropriate given their relationship or lack thereof.

The last group of strategies represented ways of responding that were clearly ineffective or were not socially competent. These included simple responses like accepting the offer, and issuing an angry or aggressive physical or verbal reply that might escalate into a confrontation. In addition, there were more complex responses lacking social competence including those that the research team labeled challenge, deny/disclaim, and distance/reflect. Challenging responses confronted the offeror with strong or profane language, name calling, or forcefully stated opinions about substance use, all without explicitly refusing the offer. Deny/disclaim responses rejected the possibility that the scenario would ever happen to them or simply insisted that the student would never use substances, without indicating how they would resist the offer. Distancing responses described internal dialogues while watching or reflecting on the scenario, rather than responding directly to it, sometimes passing negative judgment on the substance-users in the scenario, or imagining the consequences of acting or becoming like them.

The first column of Table 2 reports the relative frequency that the different types of responses appeared on the poster boards, which reflects the types of strategies the students had brainstormed most and least often in the first group sessions. Table 2 then presents the preferred (“would work every time”; n = 408) and rejected (“would never use”; n = 395) choices for responding to the scenarios. The preferred and rejected choices are first calculated as a percentage of all the times they were presented on poster boards to the respondents, and then after adjusting the percentages to add to 100% across types yet taking into account the differing frequency with which particular types of strategies were offered as potential responses. After these adjustments, there was great variability and little consensus about the type of responses that was the preferred choice overall. The most common selection was to accept the offer or pretend to use the substance (each 12–13%), followed by leaving, destroying/discarding, setting relationship boundaries, and passing (each 7–10%), and then all the other types (each 4–6%).

The strategies identified as the rejected options were more concentrated, and four strategies accounting for two-thirds of those identified as never to be used. Three of these were the least socially competent responses: accepting the substance, responding angrily or aggressively, and issuing challenging remarks. The fourth response rejected relatively often was the refuse strategy.

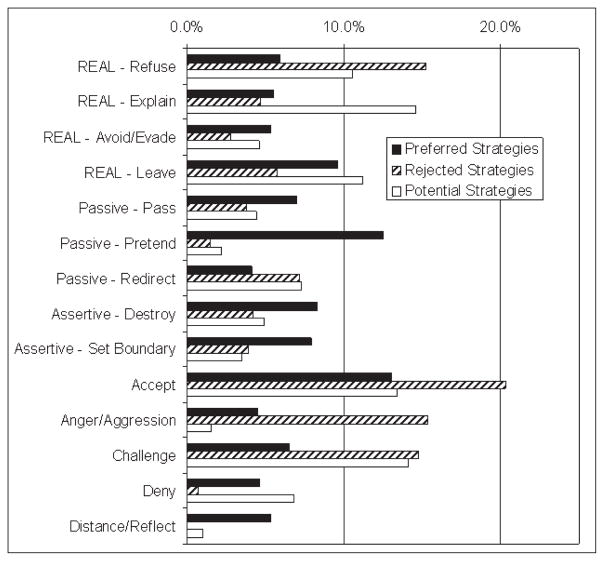

Figure 1 provides a graphic way of contrasting the preferred and rejected responses to the scenarios, relative to the frequency that these strategies emerged as potential responses. The bar chart presents the adjusted percentages of strategies falling into each type that students said “would work every time,” that they “would never use,” and that they brainstormed as potential responses to the scenarios. Two of the REAL strategies—refuse and explain—were chosen as preferred strategies far less often than they had been brainstormed as potential responses, but refuse appeared disproportionately more frequently on the list of rejected strategies. Avoid/evade and leave were nominated at similar rates as preferred and potential options, yet were mentioned less frequently as rejected responses. Destroy/discard, set relationship boundaries, pass, and pretend were all types of strategies that were brainstormed less often than they were nominated as preferred responses; they were selected as rejected responses at rates similar to their appearance in the brainstorming sessions. Redirect was mentioned at about equal rates as a rejected strategy and in the brainstorming session, but less often as a preferred strategy. Three of the least socially competent types of responses—accept, anger/aggression, and challenge—were frequently nominated as responses students would never use. However, although accept and anger/aggression were selected as rejected strategies at much higher rates than they had emerged in the brainstorming sessions, they were also selected as preferred strategies at rates similar to or exceeding their appearance in brainstorming. Deny and distance/reflect also were mentioned more often as a preferred strategy than as a rejected strategy, and at rates that approached or exceeded the brainstorming sessions.

Figure 1.

Distribution of strategies identified as preferred, rejected, and potential responses to substance offers

Table 3 presents preferred and rejected strategies broken down according to the relationship between the student and the person offering, whether the offer was from a friend, another peer, or a cousin, parent, or other extended family member (usually uncles or aunts). While Table 2 showed only slight variations overall in preferred strategies for dealing with substance offers, these preferences varied more sharply depending on the offeror. In scenarios involving friends, the strategy of passing the substance (35.0%) was nominated as the preferred choice much more often than other strategies, with accepting the offer (18.2%) a distant second choice. In scenarios with other peers, pretending to use and leaving the scene were top choices, followed by setting relationship boundaries and simply refusing the offer. For offers from cousins, the most common preferred strategy was to accept the offer, followed by challenging and angry/aggressive responses. More than half of the preferred strategies for dealing with offers from cousins were not socially competent responses, the highest percentage of any type of offeror. Destroying the substance was the top choice in offers from parents, followed by three strategies nominated at equal rates: accepting, challenging, and setting relationship boundaries. Preferred strategies for dealing with offers from other extended family members were distributed most evenly across the types, with destroy, leave, accept, avoid/evade, and distance/reflect slightly more common than others.

Table 3.

Strategies Nominated as Preferred and Rejected Responses to Substance Offers, by Relationship to Offeror

| Strategy | Preferred

|

Rejected

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friend | Other peer | Cousin | Parent | Extended family | Friend | Other peer | Cousin | Parent | Extended family | |

| R.E.A.L. | ||||||||||

| – Refuse | 8.5% | 11.8% | 2.4% | 5.5% | 4.3% | 3.7% | 4.0% | 18.6% | 6.1% | 5.7% |

| – Explain | 6.1% | 5.2% | 8.7% | 6.0% | 6.4% | 7.4% | 5.4% | 8.4% | 5.1% | 3.9% |

| – Avoid/Evade | 10.9% | 2.4% | 4.3% | NA | 12.3% | 2.5% | 1.6% | 0.0% | NA | 19.4% |

| – Leave | 0.0% | 17.7% | 1.7% | 6.6% | 13.4% | 3.2% | 8.8% | 0.0% | 6.1% | 7.7% |

| Passive | ||||||||||

| – Pass | 35.0% | 0.0% | 8.1% | NA | 2.9% | 3.6% | 4.3% | 0.0% | NA | 4.6% |

| – Pretend | NA | 18.1% | NA | NA | 4.8% | NA | 1.9% | NA | NA | 0.0% |

| – Redirect | 5.5% | 5.4% | 8.5% | 8.0% | 1.4% | 18.8% | 8.6% | 0.0% | 4.5% | 2.2% |

| Assertive | ||||||||||

| – Destroy | 2.0% | 4.1% | 5.6% | 18.1% | 15.1% | 4.0% | 10.4% | 10.9% | 1.7% | 0.01% |

| – Set Boundary | 4.4% | 14.1% | 4.2% | 11.6% | 3.5% | 0.0% | 7.2% | 0.0% | 3.3% | 0.0% |

| Non-Competent | ||||||||||

| – Accept | 18.2% | 9.4% | 23.8% | 12.0% | 12.9% | 18.4% | 14.0% | 20.8% | 34.3% | 22.5% |

| – Anger/Aggression | 0.0% | 1.9% | 12.7% | 9.2% | NA | 36.1% | 18.6% | 21.7% | 20.5% | NA |

| – Challenge | 7.0% | 2.4% | 16.2% | 12.0% | 3.9% | 0.0% | 15.1% | 19.6% | 17.2% | 34.1% |

| – Deny | 2.4% | 7.5% | 3.7% | 11.0% | 6.8% | 2.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.2% | 0.0% |

| – Distance/Reflect | NA | NA | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.3% | NA | NA | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Notes: NA: Not applicable because this type of strategy was never listed as an option in these scenarios. There was only one scenario involving adults other than family members, and those results are not presented above.

The strategies identified most often as the rejected responses to the scenarios varied somewhat by offeror, but non-socially-competent strategies predominated. Regardless of offeror, nearly half or more of the responses identified as never to be used were accept, anger/aggression, or challenge. One of these three was also the single most common choice of a rejected strategy, but that most common choice varied by offeror. About a third of the students thought that anger/aggression was the top rejected response to offers from friends, accepting the offer was the top rejected response to parents, and challenge was the top rejected response to offers from extended family members. Other than accept, anger/aggression, and challenge, three other rejected strategies emerged with some frequency but for different offerors: to never use redirect with friends, to never use refuse with cousins, and to never use avoid/evade with other extended family members.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the strategies that groups of urban American Indian middle school students identified as preferred and rejected ways of responding in hypothetical scenarios where they might encounter substance offers from different people in their family and social networks. Although these youth did not generate them, the scenarios had been described by native youth from the same metropolitan area who identified these as the types of drug use offers and opportunities that they face most frequently. Thus, the responses of the study participants to these scenarios were likely to reflect the social and cultural contexts in which the youth confront opportunities to use substances with some regularity, and their views of the preferred and rejected ways to respond. These preferences provide insights into the students’ views of socially competent ways of responding in risky situations.

Both the preferred and rejected strategies are notable in their diversity and the lack of consensus. Students identified a wide repertoire of strategies as the best and worst ways to respond. Nevertheless, some patterned preferences emerged, particularly when contrasting different groups of strategies collectively. The research team organized the strategies into four groups: REAL strategies—refuse, explain, avoid, leave—used most commonly by non-native youth; passive but effective strategies that may reflect native cultural influences; other assertive strategies; and strategies that were judged ineffective or lacking in social competence.

The REAL strategies were not generally the strategies of choice for this sample of native youth. But within this group, the two that were more passive—avoid/evade and leave—were identified as preferred options at about the rate they had been brainstormed. The more assertive REAL strategies—refuse and explain—were nominated as preferred options much less often than they had been brainstormed, and refuse was identified quite disproportionately as a rejected option, one that was never to be used. In other words, the urban American Indian youth in the sample seemed much more likely to recognize that refuse and explain were available as potential responses to the scenarios than they were to see them as preferred ways to respond. This may signal a cultural preference for more respectful responses than simple, direct refusals, which may seem abrupt in many native cultures. REAL strategies emerged as somewhat more or less salient depending on the offeror. Refuse was identified as a preferred strategy more commonly for friends and other peers than for all categories of family members, and it was a relatively common rejected option when responding to offers from cousins. It may be particularly difficult to refuse a family member, especially cousins who are often close in age. Avoid/evade was mentioned as a preferred option more often for offers from friends and extended family members, but was also a top rejected option when dealing with offers from extended family members. With friends and certain extended family members, one may have the knowledge to limit exposure to substance using situations, but that option may be less available when dealing with parents and cousins. Leaving the scene was a more common preferred option for peers and for extended family members than for friends, cousins, and parents, possibly reflecting the practicality and the consequences of removing oneself from or limiting contact with these different members of the youths’ social network.

Moving beyond the REAL group of responses, there were two passive strategies that were non-verbal—passing the substance to another person, and pretending to use it—which were mentioned as preferred strategies at rates that exceeded their appearance as options. Passing was the single most common preferred strategy for dealing with offers from friends, and pretending was the most common for dealing with other non-family peers. A third passive strategy—redirect (changing the subject)—was seldom a preferred strategy but was the most common rejected strategy for dealing with friends. The special salience of these passive strategies in situations with friends and peers may indicate a preference for methods of resisting substance use that are neither confrontational nor attention-getting when dealing with same-age peers. It is interesting that the youth focused on different ways to deal with offers from friends versus less well known peers. With friends, passing the substance may attract less attention than trying to redirect or change the subject, which may risk appearing contrived, inauthentic, or lacking group solidarity. With other peers, the strategy of pretend may seem a better option because these peers may not know the student well enough to notice or care whether the student is feigning use.

Two assertive strategies—destroy and set relationship boundaries—were also listed as preferred strategies more often than they appeared as options. Again, however, they applied mostly to specific categories of offerors. Destroy was a relatively common preferred option for dealing with offers from parents and extended family members (mostly adults), but not with friends, cousins, and other non-family peers. As noted previously, destroying the substance not only prevents the student from having to use it, it also prevents all others from using it. This consequence may make destroying the substance a difficult option with one’s age peers, and a more acceptable method with parents, uncles, and aunts. Among age peers, destroying the substance passes implied negative judgment on peers who do use substances or find such use acceptable, and may pose considerable risk of peer group rejection. While destroying substances offered by adults would seem to entail some risk of an angry reaction, with parents and adult family members it may work if it communicates the message that offering the substance to a child in the family is inappropriate.

Another assertive strategy—setting relationship boundaries—emerged as a preferred option when dealing with two very different groups: parents and peers other than friends. But the descriptions of this strategy were qualitatively different for the two types of offerors. In the case of parents, setting boundaries usually involved an implied challenge that suggested that responsible or “real” parents would not offer substances to their children. With other peers the responses coded as setting boundaries all involved a statement that the student did not know the offeror well enough to be offered substances or to accept them.

Students listed strategies that were ineffective or less socially competent responses to substance offers much more frequently as rejected than as preferred options. Of the five strategies the research team identified as relatively non-competent—accept, anger/aggression, challenge, deny, and distance/reflect—the one that emerged most commonly as a preferred option was to accept the substance. There were, however, variations by the type of offeror. Non-competent responses were listed as preferred options much more often when dealing with family members than with non-relatives. Over half the preferred options for cousin offers were non-competent, nearly half (44%) for parent offers, and over a third (36%) for other extended family member offers. By comparison, only 28% of preferred responses to offers from friends were deemed non-competent and 21% of preferred responses to other non-family peers.

One way of interpreting these patterns of non-competent responses is that their use reflects a sense of better options being unavailable. Students appeared to have more difficulty identifying a way to deal with substance offers emerging from within their family that was effective and based on skillful communication and problem solving. On the other hand, students seemed to recognize the limitations of these non-competent strategies when they listed them at high rates as rejected options, those never to be used. They were most consistent in recognizing the limitations of these strategies in the case of parents and cousins: socially non-competent strategies accounted for almost three out of four (73%) of the rejected strategies listed for offers from parents, and three out of five (62%) of the rejected strategies for offers from cousins.

IMPLICATIONS

These findings have several implications for the design of prevention efforts for urban American Indian youth. First, although native youth were aware of the REAL strategies and often listed them as possible options for dealing with many substance offer scenarios, they were much less likely to identify them as good options that “would work every time.” Training in the use of these strategies may need to recognize their relative lack of salience to urban native youth which may be due to a poor cultural fit. The students’ pattern of rejecting use of the refuse strategy in particular suggests a need for prevention programming that devises and teaches respectful ways for native youth to issue simple refusals.

Second, prevention approaches for urban native youth can be enhanced by incorporating effective strategies that are consistent with cultural values and communication preferences. The students’ preference for passive strategies like passing and pretending to use the substance in response to offers from non-family peers can be a starting point for discussions of other non-confrontational ways to deal with these offers without risking peer group rejection or disapproval. The alternatives can include the REAL strategies of avoiding/evading risky situations and leaving the scene, but these may need to be presented in a manner that acknowledges inherent limitations on their use, such as the inability of youth to control the social situations they encounter or remain in. Pass and pretend are strategies that share the characteristic of allowing the student to stay in a risky situation without using substances. The preferences they expressed for two assertive strategies—destroy and set boundaries—demonstrate that urban American Indian youth perceive creative alternative means of resisting substance offers that studies of other youth populations have not highlighted.

Third, the results include reminders of the need for prevention efforts to recognize and address specific eco-developmental influences on substance use by urban native youth. Their preferred and rejected strategies for resisting substance offers differed depending whether they came from family or non-relatives, and from age peers or adults. Offers from cousins and parents emerged as the most problematic for the youth to handle as indicated by their nomination of non-socially competent strategies as the preferred way to respond to these offers about half the time, much more often than for offers from friends, other peers, and other extended family members. Additional qualitative research on culturally appropriate and effective ways to handle these substance offers from close family members would be useful ways to inform and improve prevention approaches for this population.

LIMITATIONS

The preferred and rejected strategies that emerged in this analysis are based on a small non-probability sample drawn from two schools in one urban area. Thus, the results are quite limited in generalizability. Although the families of the youth did represent an array of tribal backgrounds, their responses may reflect cultural expressions that are somewhat specific to the urban American Indian community in the Phoenix metropolitan area. In addition, the sample was recruited in a way such that youth and families who embraced their native heritage and may have had a strong sense of American Indian identity were self-selected. Students were eligible for the study only if they were in a native cultural heritage program to which they had been invited based on lists of students whose parents indicated they were American Indian. The results may differ for a sample including native students who were less motivated to learn about their cultural heritage and/or had parents who identified less strongly as American Indian.

The results are also open to interpretation concerning how clearly the preferred and rejected ways of dealing with substance offers reflected the personal inclinations and past experiences of the respondents. Because the students had varied degrees of exposure to the substance offer scenarios presented to them, and to avoid eliciting socially desirable responses in group settings, the research team decided not to ask the students how they had actually responded to these scenarios in the past. Nor were they asked how they thought they would respond in the scenarios (only how they would not respond). Instead they were asked to identify which strategies would generally be effective (or “work every time”) for youth like them. It is likely that some preferred strategies might not actually be used by the students who nominated them, especially those describing aggressive and challenging responses that could put the student at further risk. Future research can be directed toward more precise measurement of strategies that urban American Indian youth use in real rather than hypothetical substance offer scenarios they might face.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite these limitations, reports from this convenience sample provide indications of the types of drug resistance strategies that urban American Indian youth find most and least useful when dealing with substance use opportunities, and suggestive evidence of eco-developmental and cultural influences on these preferences. Although they frequently brainstormed the REAL strategies—refuse, explain, avoid, leave—that predominate in the repertoire of youth from other ethnic backgrounds, the native youth typically did not identify these as the best way to deal with substance offers. Prevention efforts for urban American Indian youth may need to adapt these strategies and the way they are taught. The alternative strategies that native youth gave higher priority included an impressive range, from passive and non-verbal strategies like passing on or pretending to use the substance, to assertive strategies like destroying the substance and questioning the appropriateness of the offer. Because these alternative strategies allowed the youth to remain present in social settings they may not be able or may not want to exit, these may be important strategies for cultural reasons as well as reflections of the social contexts in which they encounter substance offers. Prevention efforts can also build on the students’ recognition of strategies that are not socially competent, which made up the majority of those they rejected. Finally, patterns of preferred and rejected strategies varied depending on the relationship to the offeror, suggesting that prevention efforts need to recognize and be tailored to a variety of specific social contexts where native urban youth face the greatest risk of substance use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patricia Dustman, Marissa O’Neill, and Leslie Reeves for assistance with the original qualitative coding of the data, and Maureen Olmsted for assistance in developing the strategy for the quantitative analysis.

Footnotes

Data collection for this study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R-24 DA 13937-01, F. F. Marsiglia, PI) and data analysis was supported by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20-MD002316-03, F. F. Marsiglia, PI; P20-MD002316-039001, S. Kulis, PI) for the project “Culturally-Specific Substance Abuse Prevention for Urban American Indian Youth” (P20- MD002316-030004, E. F. Brown, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ackerman L. Residential mobility among the Colville Indians. Washington, DC: Center for Survey Methods Research, Bureau of the Census; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman L. Residents or visitors: Finding motives for movements in an Indian population. Paper presentation at the Society for Applied Anthropology; Santa Fe, New Mexico. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts JK, Miller-Rassulo MA, Hecht ML. A typology of drug resistance strategies. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 1991;19:129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Alvord L, Van Pelt E. The scalpel and the silver bear: The first Navajo woman surgeon combines Western medicine and traditional healing. New York: Bantam Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arguelles L, Buchwald D, Garroutte EM, Goldberg J, Sarkisian N. Cultural identities and perceptions of health among health care providers and older American Indians. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arizona Public Health Association. Report prepared through the Office of Minority Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention; Rockville, MD: 2005. Health disparities in Arizona’s racial and ethnic minority populations: Living and dying in Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Indian Physicians. 2005 http://www.aaip.com/resources/alcohol.html Retrieved February 13, 2005.

- Baldwin JA, Maxwell CJ, Fenaughty AM, Trotter RT, Stevens SJ. Alcohol as a risk factor for HIV transmission among American Indian and Alaska Native drug users. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2000;9:1–16. doi: 10.5820/aian.0901.2000.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates SC, Beauvais F, Trimble JE. American Indian adolescent alcohol involvement and ethnic identification. Substance Use and Misuse. 1997;32(14):2013–2031. doi: 10.3109/10826089709035617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F. Drug use of friends: A comparison of reservation and non-reservation Indian youth. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1992;5(1):43–50. doi: 10.5820/aian.0501.1992.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F. American Indians and alcohol. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1998;22:253–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F, Trimble JE. The effectiveness of alcohol and drug abuse prevention among American-Indian youth. In: Sloboda Z, Bukoski WJ, editors. Handbook of drug abuse prevention: Theory, science, and practice. New York: Kluwer; 2003. pp. 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Bonvillain N. Ethnographic Exploratory Research Report #5. Center for Survey Methods Research, Bureau of the Census; Washington, DC: 1989a. Residence patterns at the St. Regis Reservation. [Google Scholar]

- Bonvillain N. The census process at St. Regis Reservation. Center for Survey Methods Research, Bureau of the Census; Washington, DC: 1989b. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin G. Advancing prevention science and practice: Challenges, critical issues, and future directions. Prevention Science. 2004;5:69–72. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013984.83251.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW. Drug abuse prevention curricula in schools. In: Sloboda Z, Bukoski WJ, editors. Handbook of drug abuse prevention: Theory, science, and practice. New York: Kluwer; 2003. pp. 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Ifill-Williams M. Preventing binge drinking during early adolescence: One- and two-year follow-up of a school-based preventive intervention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15(4):360–365. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Schinke SP, Epstein JA, Diaz T. Effectiveness of culturally focused and generic skills training approaches to alcohol and drug abuse prevention among minority youths. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8(2):116–127. [Google Scholar]

- Browne AJ, Fiske J. First Nations women’s encounters with mainstream health care services. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2001;23(2):126–147. doi: 10.1177/019394590102300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castor ML, Forquera RA, Lawson SA, Park AN, Smyser MS, Taualii MM. A nationwide population-based study identifying health disparities between American Indians/Alaska Natives and the general populations living in select urban counties. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(8):1478–1484. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Death rates and number of deaths by state, race, sex, age and cause, 1994–1998. Atlanta, GA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Healthy youth! Addressing health disparities. 2006 Retrieved October 8, 2006 from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/healthtopics/disparities.htm.

- Chavez V, Duran B, Baker QE, Avila MM, Wallerstein N. The dance of race and privilege in community based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2003. pp. 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chewning B, Douglas J, Kokotailo PK, LaCourt J, Clair D, Wilson D. Protective factors associated with American Indian adolescents’ safer sexual patterns. Maternal and Child Health. 2001;5(4):273–280. doi: 10.1023/a:1013037007288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AS. Social and emotional distress among American Indian and Alaska Native students: Research findings. [Electronic Version] Charleston, WV: ERIC Digest; 2002. Retrieved March 4, 2005, from http://www.ael.org/page.htm?andid=503andpd=res8721. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, McBride C, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopmental correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6(3):126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M. Access to care issues for Native American consumers. In: Dixon M, Roubideaux Y, editors. Promises to keep: Public health policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2001. pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon AL, Yabiku ST, Okamoto SK, Tann SS, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, et al. The efficacy of a multicultural prevention intervention among urban American Indian youth in the Southwest U.S. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28:547–568. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0114-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi SC, DiLorenzo TM. An evaluation of a tobacco use education-prevention program: A pilot study. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1993;5:73–78. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90124-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorpat N. PRIDE: Substance abuse education/intervention program. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: Journal of the National Center. 1994;4:122–133. doi: 10.5820/aian.mono04.1994.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran BG, Wallerstein N, Miller WR. New approaches to alcohol interventions among American Indian and Latino communities: The experience of the Southwest Addictions Research Group. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Duran B, Walters KL. HIV/AIDS prevention in “Indian country”: Current practice, indigenist etiology models, and postcolonial approaches to change. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:187–201. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.3.187.35441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenaughty AM, Fisher DG, Cagle HH, Stevens S, Baldwin JA, Booth R. Sex partners of Native American drug users. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1998;17:275–282. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199803010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JW, Moore RS, Ames GM. Historical and cultural roots of drinking problems among American Indians. American Journal of Public Health. 2000 doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett MT, Carroll JJ. Mending the broken circle: Treatment of substance dependence among Native Americans. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2000;78(4):379–388. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett MT, Herring RD. Honoring the power of relation: Counseling Native adults. Journal for Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development. 2001;40:139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist L, Schinke SP, Trimble JE, Cvetkovich G. Skills enhancement to prevent substance abuse among American Indian adolescents. International Journal on the Addictions. 1987;22:869–879. doi: 10.3109/10826088709027465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosin M, Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. keepin it R.E.A.L.: A drug resistance curriculum tailored to the strengths and needs of pre-adolescents of the southwest. Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33(2):119–142. doi: 10.2190/DXB9-1V2P-C27J-V69V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Wilson DB. Characteristics of effective school-based substance abuse prevention. Prevention Science. 2003;4:27–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1021782710278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Nichols T. Long-term follow-up effects of a school-based drug prevention program on adolescent risky driving. Prevention Science. 2004;5(3):207–212. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037643.78420.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Nichols TR, Scheier LM. Low perceived chances for success in life and binge drinking among inner-city minority youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34(6):501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin J. Urban renegades: The cultural strategy of American Indians. New York: Columbia University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EH, Cummins LH, Marlatt GA. Preventing substance abuse in AI and Alaska Native youth: Promising strategies for healthier communities. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(2):304–323. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Alberts JK, Miller-Rassulo M. Resistance to drug offers among college students. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1992;27(8):995–1017. doi: 10.3109/10826089209065589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Corman SR, Miller-Rassulo M. An evaluation of the drug resistance project: A comparison of film versus live performance media. Health Communication. 1993;5(2):75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek-Fisk E, Wagstaff DA, Kulis S, Dustman P. Culturally-grounded substance use prevention: An evaluation of the keepin’ it REAL curriculum. Prevention Science. 2003;4(4):233–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1026016131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Ribeau S, Alberts JK. An Afro-American perspective on interethnic communication. Communication Monographs. 1989;56:385–410. [Google Scholar]