Survivorship care plans were highly valued by these primary care providers, increasing their knowledge about survivors' cancer history and influencing patient management.

Abstract

Introduction:

The growing numbers of cancer survivors will challenge the ability of oncologists to provide ongoing surveillance care. Tools such as survivorship care plans (SCPs) are needed to effectively care for these patients. The UCLA-LIVESTRONG Survivorship Center of Excellence has been providing SCPs to cancer survivors and their providers since 2006. We sought to examine views on the value and impact of SCPs from a primary care provider (PCP) perspective.

Methods:

As part of a quality improvement project, we invited 32 PCPs who had received at least one SCP to participate in a semistructured interview focused on (1) the perceived value of SCPs for patient management and (2) PCP attitudes toward follow-up care for cancer survivors. Interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed.

Results:

Fifteen PCPs participated in the interviews and had received a total of 30 SCPs. Ten of them indicated reading the SCPs before being contacted for the interview. All 10 PCPs indicated that the SCP provided additional information about the patient's cancer history and/or recommendations for follow-up care, and eight reported a resulting change in patient care. PCPs identified useful elements of the SCP that assisted them with patient care, and they valued the comprehensive format of the SCP. PCPs indicated that after reading the SCPs they felt more confident and better prepared to care for the cancer survivor.

Conclusion:

SCPs were highly valued by these PCPs, increasing their knowledge about survivors' cancer history and recommended surveillance care and influencing patient care.

Introduction

Over the past three decades, the number of cancer survivors in the United States has increased more than threefold, with approximately 12 million cancer survivors today.1 These survivors are at risk for various physical and psychosocial long-term and late effects of cancer treatment. Although most receive good quality cancer care, they may experience difficulties in accessing appropriate post-treatment follow-up care, risking poorer health outcomes.2

The question of who should be responsible for coordinating the routine follow-up care of cancer survivors has received much attention.3–6 Several studies demonstrate that primary care providers (PCPs) can provide the same quality care as oncologists during recurrence surveillance.7–10 In addition, sole care by oncologists may lead to neglect of many important noncancer-related health processes.11 Indeed, some reports show that quality of cancer care is optimal when it is shared by oncologists and PCPs.5,12,13 Also, with the increasing volume of patients with cancer, it may be more efficient to transition surveillance care to PCPs and follow a shared-care model.3,14,15

The World Health Organization views the integration of PCPs into cancer care as a key step in coordinated and comprehensive care16; however, PCPs may need guidance to participate in post-treatment survivorship care.17,18 To facilitate this activity, the Institute of Medicine recommended that patients with cancer and their PCPs receive a written survivorship care plan (SCP) at the end of active treatment.2 However, little is known about how PCPs who receive SCPs perceive and use them, and whether SCPs are a useful means of communication between PCPs and medical oncologists.19 Studies to date have addressed only the hypothetical implementation of a “draft-template” and the “preferred” or “proposed content” of an SCP for a fictitious patient.20–22

Since 2006, the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) -LIVESTRONG Survivorship Center of Excellence (COE) has been providing survivorship consultations and sending SCPs to PCPs. As a quality improvement (QI) activity, we embarked on a qualitative evaluation of the value of the SCP in the setting of a large, university-affiliated comprehensive cancer center. The objectives of this QI project were to explore the views of PCPs on the perceived value of the SCP in patient management and PCP attitudes toward follow-up care for cancer survivors.

Institutional Setting

The COE clinical program has two clinics that provide comprehensive survivorship consultations for adult and childhood cancer survivors. Consultative services are provided by a specialized multidisciplinary team, including either a medical or pediatric oncologist with expertise in cancer treatment long-term and late effects, symptom management, cancer surveillance, and risk reduction strategies for common organ toxicities and second malignancies; a nurse practitioner who focuses on diet, nutrition, and health/wellness counseling; and a psychologist or oncology social worker who screens for depression and other psychosocial needs.

The survivorship team creates SCPs that include a detailed cancer treatment history, current medications, and recent surveillance testing results, as well as tailored recommendations for management of late effects, evidence- or consensus-based guidelines for surveillance, and appropriate referrals as needed. The SCP is sent to the patient and to all physicians currently involved in the patient's care and is stored in the UCLA electronic medical record for future reference.

Methods

Procedures and Participant Recruitment

Qualitative methods were used to assess PCP attitudes toward the SCP.23 A semistructured interview guide was developed by the research team, with open-ended questions followed by concurrent standardized and ad hoc probes (Data Supplement). The interview included (1) background questions about PCPs and their practice, (2) evaluative questions about PCP views on the impact of the SCP and survivorship clinic services on patient management, and (3) attitudes about responsibility for cancer survivor follow-up care. The UCLA institutional review board approved the activity, and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

The COE consultation database was used to identify all UCLA-affiliated PCPs (internists, family practice physicians) who had received an SCP between November 2006 and July 2009. PCPs were eligible if they had received at least one SCP and were still affiliated with UCLA. Thirty-two PCPs were identified, and all were invited to participate in the QI activity by an introductory invitation letter from the director of the COE. All recruitment efforts were conducted within a 6-week period by the interviewer, a PCP who was independent of the COE clinical program. Up to three follow-up e-mails were sent in an attempt to schedule an interview. For nonresponsive PCPs, a personal telephone call was made as the final attempt to schedule an interview. Interviews were conducted between September 8 and November 16, 2009, either in person or by telephone. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, with the exception of one PCP who declined to be recorded and for whom handwritten notes were taken. All interviews and transcripts were coded with unique identifiers to ensure confidentiality of the participants.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative data analysis was conducted according to strategies developed by Huberman and Miles.24 Analysis consisted of a series of steps including identification of themes, developing codes, and organization of categories. This process is rooted in the constant comparative method of grounded theory.25 To categorize the transcribed interview text into different themes, a code book was developed based on the interview question guide and interview notes. NVivo-8 software (QSR International, Cambridge, MA) was used to assist with text management and systematic coding.26 Two independent coders (M.M.S. and E.E.H.) analyzed the interview transcripts and notes. During the process of analysis, additional themes were added to the code book. Before agreement rates between the coders were calculated, 14 major themes (out of 27) were identified as being relevant to this article. The full text of all interviews was used as the reliability sample, comparing the results of coders for these 14 themes. As a result of the conversational nature of the interview transcripts, we expected to find variation in the way coders bounded each text unit for coding to a specific theme. The surrounding peripheral text captured with each text unit can vary between coders.27 Thus, agreement was verified if both researchers coded the same main text unit into the same theme, allowing for text-length variation within five lines. Cohen's kappa was calculated to measure intercoder reliability.28 There was an 82.5% agreement rate between coders. In cases where differences in theme identification arose between the coders, they were further reviewed and resolved.

Results

Participant Characteristics

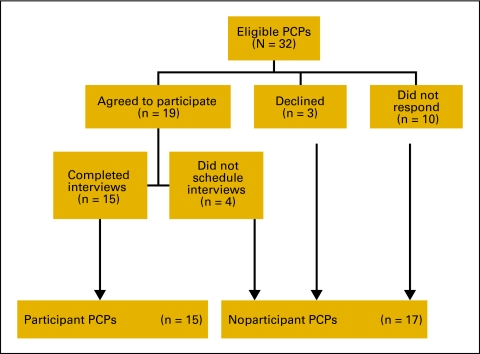

Of the 32 PCPs, 19 initially agreed to be interviewed, three declined, and 10 did not respond. Of the 19 PCPs who agreed to be interviewed, 15 completed the interview: nine in person and six by telephone (Figure 1). The main reason given for nonparticipation was lack of time. This response rate is similar to the mean response rate to mailed surveys among physicians, which is reported to be 54%.29 Characteristics of all PCPs and the SCPs received are shown in Appendix Table A1 (online only). There were no major differences between the participants and nonparticipants. Both groups were primarily internists, were more likely to be female, and received a similar distribution of SCPs. Overall, 30 SCPs were sent to the 15 PCPs interviewed (two SCPs on average; range, 1-10).

Figure 1.

Participant response rates. Of the 32 primary care providers (PCPs) invited to participate in the quality improvement project, 19 agreed to be interviewed and 15 completed the interview; three declined to participate.

Themes and Findings

SCP provided new information about patient's cancer history and recommendations for follow-up.

Ten of the 15 PCPs interviewed remembered having read the SCP before being contacted for the interviews. Those who did not remember the SCP reported reviewing the document before or during the interview, although it was not required that they do so. (It should be noted that the SCP is stored in an electronic medical record, allowing the PCPs to easily access and review the document as needed.) All 10 PCPs reported that the SCP had provided additional information about at least one of their patients' cancer history (n = 1), recommendations for follow-up care (n = 4), or both (n = 5). All 15 PCPs appreciated receiving a single comprehensive document for the patient's medical record that could be used for future reference. They reported that the summary considerations provided considerable value and resulted in greater efficiency in follow-up care for these patients. Even when the SCP did not provide new information, its recommendations provided reassurance and confirmation (Appendix Table A2, online only).

SCP changed survivor care.

Of the 10 PCPs who remembered and read the SCP before the interview, eight reported a resulting change in patient care and could remember and provide explicit examples of this change during the interview. The SCPs also assisted PCPs in updating and organizing the problem list of their patients, making it easier to complete the follow-up recommendations. In addition, PCPs mentioned that the recommendations facilitated health insurance approvals and reimbursement for recommended tests (Appendix Table 3, online only).

Importance of having an expert oncologist in the survivorship clinic.

Having an expert oncologist in the survivorship clinic was important to all 15 PCPs. They expressed greater confidence about recommendations written (or at least approved) by an oncologist. They also emphasized that this is particularly important in complex cases, like those commonly seen at a tertiary medical center, and especially with the childhood cancer survivors. PCPs were not sure whether they would read the SCP and accept its recommendations if it were prepared solely by a nurse practitioner. Seven PCPs added that a nurse practitioner would be acceptable in the simple cases, but with the more complicated patients or when expensive testing is being recommended, an oncologist is essential (Appendix Table A4, online only).

PCPs wish to continue receiving SCPs.

All PCPs stated that they value the SCPs and that they would like to continue receiving them. However, some PCPs made comments demonstrating concern that the SCP might generate extra or unnecessary work for the PCP; for example, “I don't know how much stuff they find that primary care doctors don't know and don't do. If the [survivorship] clinic is generating a lot of extra work that isn't likely to terribly benefit the patients, then I think [it] shouldn't exist.”

SCP length and comprehensiveness.

The average length of an SCP received by the participant PCPs was 5.3 pages (range, 3-7 pages). The length was considered appropriate by all PCPs, with variation according to the complexity of the case. PCPs noted that they frequently turned to the recommendations section of the SCP as this was most useful; however, they still preferred a comprehensive SCP format in case they needed to refer to the past treatment information. As one participant noted, “… in that way it helped me focus more on analyzing the patient as opposed to having to collect a lot of data, because it was all put together, which I felt was very, very helpful.”

SCP increased PCP's confidence and preparedness to participate in the shared-care model for cancer survivors.

On the basis of an operational definition of shared-care between primary and specialty providers for cancer survivors from Oeffinger and McCabe,6 all 15 PCPs reported a willingness to accept either sole or shared responsibility for the routine follow-up care of their patients, especially if they were provided with a SCP. Four PCPs added that their willingness also depends on the specific type of cancer, its complexity, and the type of the follow-up tests required. Six of the 10 PCPs who had previously used the SCP reported that the SCP made them feel more confident and empowered to care for their patients, allowing them to have more time to focus on implementing the recommendations. Four of the 10 stated that the SCP didn't change their attitude, as they were already positively inclined to provide such care.

Most useful elements of the SCP.

Overall, PCPs were very pleased with the SCPs they had received. On a 1 to 10 scale, PCPs rated their satisfaction as high, with a mean score of 8.9 (range, 7.5-10). The PCPs identified nine most useful elements of the SCP, some of which are quite similar to the 2005 Institute of Medicine report.2 Seven of the nine elements are related to the comprehensiveness of the SCP, and two of them refer to its evidence-based nature (Appendix Table 5, online only). PCPs highlighted the benefit of having external and historic cancer treatment information summarized clearly in one document, saving time and eliminating the challenge of personally retrieving this information. Second, the SCP lists the names of the providers who were involved in the patient's cancer treatment, which was valuable in facilitating further consultations, especially when patients didn't remember all the providers involved in their care. Also, providing information on possible late effects of cancer treatment was useful to PCPs, as it allowed incorporation of appropriate monitoring and future screening (eg, for late cardiac effects). Importantly, PCPs stressed the fact that recommendations were evidence based, which facilitated the approval and reimbursement for the recommended tests by the health insurance companies. And lastly, PCPs also found that providing evidence-based information on tests that have not been shown to increase survival and therefore are not recommended for regular follow-up care was very helpful. PCPs felt this information provided support in their discussions with patients who requested unnecessary tests and procedures (see other elements in Table A5).

In addition, PCPs suggested the following improvements to the SCP document:

SCPs should clearly specify which follow-up recommendations and tests the oncologist is responsible for and which should be completed by the PCP.

Survivorship clinics should educate PCPs about the mechanisms of referral and the types of cancer survivors who would benefit the most from a consultation, as it may be wasteful to refer all survivors without considering the cancer type and time elapsed since diagnosis.

Recommendations to other specialists should be limited, as many PCPs felt they could carry out the recommendations themselves or decide whether a specialist referral was necessary.

Putting the specific recommendations in tabular format with a brief summary would increase the usability of the SCP.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to explore views on the perceived value and usefulness of SCPs from the perspective of the PCPs who have been receiving them. Other research related to this topic has addressed only the hypothetical receipt of a SCP and whether it would potentially be useful in patient care.20–22 In conducting this QI activity, we learned about PCP views on the value and impact of SCPs among 15 busy PCPs in a large comprehensive cancer center. We were uncertain how usable and valuable the SCP would be to PCPs in a busy academic clinical setting, where physicians might be more up-to-date on the latest evidence-based recommendations. We found that despite their work overload, two thirds of physicians interviewed had read and used the SCPs they had received even before we contacted them for the interview, and could comment in some detail about their strengths and limitations. Moreover, all the PCPs who remembered initially receiving and reading the SCP indicated it added new information, and 80% of them reported a resulting change in their patients' care. This occurred even though 73% of the SCPs were for survivors of breast cancer, a common disease for which PCPs are likely to be quite knowledgeable. It may be that for rarer and more complex cancers SCPs could yield even greater value. Furthermore, physicians were highly satisfied with the SCP, noting the self-efficacy it promoted. We were surprised that the length of the SCP document was not a burden given the heavy clinical load of the PCPs; rather, the comprehensiveness of the SCP was greatly valued.

This QI project has several limitations. The small sample size may affect the generalizability of the findings. However, because little is known about the SCP's acceptability and value to PCPs, we chose to use qualitative methods and to study a small number of individuals rather than survey a large sample.30 This allowed for greater in-depth exploration of PCPs' perspectives. In addition, the unique setting of the study and characteristics of its participants may also limit the generalizability of these findings. The academic orientation of these PCPs and the fact that they are employed in the same medical setting as the COE clinicians may enhance their compliance with specialist recommendations; this unique combination may have resulted in overestimating the SCP's perceived impact. However, because the vast majority of cancer survivorship centers in existence today are operating in academic settings, these results may be relevant and generalizable to other academic centers. Finally, the lack of a comparison group is also a limitation. Future research evaluating the effectiveness of SCPs will ideally include pre- and postintervention data and a control group.

Although this QI project was undertaken with a small group of providers within a single academic institution, the themes and findings from this project may serve as a useful knowledge base for studies on the impact of SCPs. Program evaluation and projects of this type are a valuable tool in developing sustainable clinical programs that allow for effective and efficient high-quality care.

The results from this QI project suggest that the PCPs who have been receiving SCPs view them quite favorably and feel that SCPs provide new information on cancer treatment history and recommendations for future care. In addition, PCPs felt that the SCP assisted with patient care and with updating and organizing their patients' problem lists. Planning of this type is particularly needed in cancer care, where patients have multiple treating oncology physicians and may be lost to follow-up by the PCP for periods ranging from months to years.

These results can be used in oncology practices that are currently using or are planning to use SCPs. The current fragmentation of care and poor communication between specialists and PCPs increases the likelihood of both overuse of tests and procedures as well as underuse of necessary surveillance and preventive services. The use of SCPs to facilitate the coordination of post-treatment cancer care may be a critical first step in improving outcomes for the growing number of cancer survivors.

Acknowledgment

Supported in part by the Lance Armstrong Foundation.

Appendix

Table A1.

Characteristics of Primary Care Providers and Survivorship Care Plans

| Characteristic | Participant PCPs (n = 15) |

Nonparticipant PCPs (n = 17) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 9 | 60 | 9 | 53 |

| Male | 6 | 40 | 8 | 47 |

| Age, years | ||||

| Average | 48.1 | Not available | ||

| Range | 39-62 | |||

| Time elapsed since PCP graduated from medical school, years* | ||||

| Average | 21.9 | 26.4 | ||

| Range | 6-36 | 5-46 | ||

| Specialty† | ||||

| Internist | 10 | 66.6 | 13 | 76.5 |

| Family physician | 5 | 33.3 | 3 | 17.6 |

| Pediatricians | 1 | 0.07 | 1 | 5.9 |

| No. of SCPs sent to each PCP before the interview | ||||

| Average | 2 | 1.7 | ||

| Range | 1-10 | 1-9 | ||

| Total No. of SCPs sent to all PCPs | 30 | 29 | ||

| No. of SCPs sent stratified by cancer diagnosis | ||||

| Breast cancer | 22 | 73.3 | 15 | 51.7 |

| Other cancers‡ | 8 | 26.7 | 14 | 48.3 |

| SCP length, No. of typewritten pages | ||||

| Average | 5.3 | 5.9 | ||

| Range | 3-7 | 4-9 | ||

| Time elapsed since SCP was sent to PCP until study conducted, months‖ | ||||

| Average | 18.7 | 12.6 | ||

| Range | 2.3-34.1 | 1-35.5 | ||

Abbreviations: PCP, primary care provider; SCP, survivorship care plan.

Time elapsed was calculated by subtracting the year of medical school graduation from 2009.

Totals are exceeded because one of the 10 internists specialized in both internal medicine and pediatrics.

Other types of cancer included hematologic malignancies (leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma), ovarian, thyroid, synovial sarcoma, appendix, kidney, prostate, and neuroblastoma.

Because all interviews were conducted between September and November 2009, we used October 30 as the study period for both the participant and nonparticipant PCPs.

Table A2.

Survivorship Care Plans Provided Additional Information and Reassurance to Primary Care Providers

| Themes | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| Information on patient's cancer history | “It did [provide additional information], almost always, because records here are inadequate, plus many patients were treated outside UCLA.” “A lot of times I didn't know that they had surgery or they had radiation. I don't necessarily know all the detail of the cancer type, because the patients don't typically know that. So I thought that was a really nice summary not necessarily for me per say, but for the medical record. Should she or he ever have diagnosis again we would know in very details, in one single place … the pathology, the treatment history, the radiation history … and who were the prior treating physicians; that was nice for me.” |

| Information on recommendations for follow-up | “He is a Hodgkin's survivor … he needed an ultrasound for his carotid because of the radiation, and I would have never gotten that. I would have never occurred to me … Oh, another one required a cardiac echo … and I would not have known that, and it was because of the chemotherapy she received … ” |

| Recommendations assisted PCP with efficient time management | “The recommendations were new. So, I mean, I know where to find them. I know the websites to get them. But it would literally take me not even hours—I mean— it would take me days to ferret through for one patient … ” “The fact that all the data had been collected and organized … [allowed me to] pay much more closer attention to the assessment and plan … [the SCP] helps me … as a reminder in the future, “ding ding ding, when this patient walks in: remember! Here's your little road map' So, I think in that way it helped me focus more on analyzing the patient as opposed to having to collect a lot of data, because it was all put together, which I felt was very, very helpful.” |

| SCP provided reassurance and confirmation | “One of the things for us as primary care doctors is that these sorts of reports can really serve as a learning process, so you would expect that by the time you get the tenth or eleventh one, it may not surprise you–you'd probably know what you're supposed to do. But, yet it's still incredibly useful to have the summary of the treatment and also to have the oncologist really sign off on “yes, this patient gets sort of the standard thing that you've learned how to do' or “there's some special element that you need to consider.'” “I wouldn't get rid of it … I would keep it because it confirms … “Oh that's what I'm doing, I did do that' versus if there was something here and I was like-“oh I'm not doing that'-then that's good because it's nice to know that. But, on the other hand it's also nice to be reassured.” |

Abbreviations: PCP, primary care provider; SCP, survivorship care plan.

Table A3.

Survivorship Care Plan Changed Delivery and Organization of Patient Care

| Themes | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| SCP changed patient's management | “It did [changed management]. I would only do DEXA scans on her every 5 yr if at all, but she's been getting it every two years since then. But, in this case, based on what was written, it sounded like it was worth doing this test more often.” |

| SCP assisted in updating and organizing patient's problem list | “The surveillance piece I thought was very good, because in that way I was able to update my problem focus list and make sure I had some target dates to drive when things needed to happen, so I thought that was good. Also … now when I see a patient that may not be part of the survivorship program I go “ok, these are the things to (do) … this is the way to organize the thinking.” |

| Recommendations facilitated health insurance approval and payment for tests | “One of the patients I remember because she had Hodgkin's lymphoma as a child and she had radiation therapy to her chest, and of course that put her at higher risk for breast cancer … and it was the first year the recommendations came out for doing the MRI's for breast cancer screenings for very high risk patients like that. So … I'd heard of it, but [the SCP] actually helped because without that she wouldn't have gotten it covered by her insurance company.” |

Abbreviation: SCP, survivorship care plan.

Table A4.

Primary Care Providers' Comments on Survivorship Consultations

| Themes | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| Having an expert oncologist is important | “Oh, I think [having an oncologist] is absolutely essential to me, that's really the added value to this. … I think the key to this, for us as physicians, is— this is really a new area. People in the past have not really thought about how you take care of a survivor and so it's not protocolized. There's a lot of new information all the time so it's not really something that I think can be sort of routinely done.” “I'm a general internist … the type of patient that I would send there, I would really expect to get an oncologist's opinion, because by definition, that would be somebody complicated.” “It's important … because what I care about is the clinical synthesis, thankfully. I probably wouldn't send them over if there wasn't a doctor.” |

| An expert oncologist is particularly critical in complex cases | “In the case of my patient it's different from some more common malignancies like breast and colon cancer, where I would have a pretty good idea of what the regular follow up routine would be. With leukemia and diseases like that you need someone who knows how to stay on top of what needs to be done.” “I think that at a tertiary medical center like here, where I see patients maybe a little bit more complicated … it's important that maybe an expert oncologist see it.” “It can be stratified for certain illnesses. Maybe breast cancer can be some of the more standard illnesses, but childhood illnesses are a little more different; treatment plans can change quite a bit over the last several years.” |

| Hesitations about accepting recommendations written solely by a nurse practitioner | “Within a survivorship program, you could certainly have different providers for different tracks … You certainly could have a well-trained nurse practitioner who could give you the plan for a 65-yr-old woman who had a stage I breast cancer … I think where having the oncology oversight is so important … is in these more complicated cases, where patients have received multiple types of chemotherapy and there may be uncertainty or disagreement on what the follow-up should be.” “The other risk that I have seen working with some nurse practitioners … is again this whole issues that for us as primary care doctors, you better have the evidence for things that you recommend that cost money. If you say that this patient needs a breast MRI, you better have a good reason that I can give her insurance company because if you don't, then the patient's pissed off, I'm pissed off; it's just not going to work.” |

Table A5.

Important Elements of a Survivorship Care Plan From a Primary Care Provider Perspective

| Characteristic | Element |

|---|---|

| SCP is comprehensive and detailed | |

| 1 | All the information about the patient's cancer history is collected from different provider sources and summarized clearly in one document |

| 2 | Lists the names of all providers who were involved in patient's cancer treatment |

| 3 | Is based on a multidisciplinary approach; diet, exercise and psychosocial aspects are addressed. |

| 4 | Includes different alternatives of course of action and the patient is included in the decision making process |

| 5 | Provides information on possible late effects of cancer treatment |

| 6 | Includes information on genetic counseling and testing to identify high risk individuals |

| 7 | Lists the specific resources for psycho-social support for the patient |

| SCP is evidence based | |

| 8 | The recommendations in the SCP are evidence-based |

| 9 | Also lists the tests that were not shown to increase survival and therefore are not recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology for regular follow-up care of a cancer survivor |

Abbreviation: SCP, survivorship care plan.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Marina Mor Shalom, Erin E. Hahn, Jacqueline Casillas, Patricia A. Ganz

Administrative support: Marina Mor Shalom, Patricia A. Ganz

Collection and assembly of data: Marina Mor Shalom, Erin E. Hahn

Data analysis and interpretation: Marina Mor Shalom, Erin E. Hahn, Jacqueline Casillas, Patricia A. Ganz

Manuscript writing: Marina Mor Shalom, Erin E. Hahn, Jacqueline Casillas, Patricia A. Ganz

Final approval of manuscript: Marina Mor Shalom, Erin E. Hahn, Jacqueline Casillas, Patricia A. Ganz

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer Survivors — United States, 2007. MMWR. 2011;60:269–72. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5324a3.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2006. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, et al. Primary care physicians' views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3338–3345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weller D, McGorm K. GP versus hospital follow up for cancer patients. Is the choice based on evidence? Aust Fam Physician. 1999;28:356–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: Improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5112–5116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5117–5124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunfeld E, Mant D, Yudkin P, et al. Routine follow-up of breast cancer in primary care: Randomised trial. BMJ. 1996;313:665–669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7058.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, et al. Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: A comparison of family physician versus specialist care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:848–855. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wattchow DA, Weller DP, Esterman A, et al. General practice versus surgical-based follow-up for patients with colon cancer: Randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahboubi A, Lejeune C, Coriat R, et al. Which patients with colorectal cancer are followed up by general practitioners? A population-based study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2007;16:535–541. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32801023a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganz PA, Casillas J, Hahn EE. Ensuring quality care for cancer survivors: Implementing the survivorship care plan. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101:1712–1719. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Earle CC, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, et al. Quality of non-breast cancer health maintenance among elderly breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1447–1451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shulman LN, Jacobs LA, Greenfield S, et al. Care and cancer survivorship care in the United States: Will we be able to care for these patients in the future? J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:119–123. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0932001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, et al. Future supply and demand for oncologists: Challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Policy and Managerial Guidelines. ed 2. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. National Cancer Control Programmes. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 18.President's Cancer Panel. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2004. Living Beyond Cancer: Finding a New Balance. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganz PA, Hahn EE. Implementing a survivorship care plan for patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:759–767. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, et al. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: Qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2270–2273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson EK, Sugden EM, Rose PW. Views of primary care physicians and oncologists on cancer follow-up initiatives in primary care: An online survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:159–166. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0117-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baravelli C, Krishnasamy M, Pezaro C, et al. The views of bowel cancer survivors and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: An introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:42–45. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miles MB, Huberman AM. ed 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strauss A, Corbin J. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cambridge, MA: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2008. QSR NVivo 8: Software for Qualitative Analysis, Version 8 [computer program] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurasaki KS. Intercoder reliability for validating conclusions drawn from open-ended interview data. Field Meth. 2000;12:179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lombard M, Snyder-Duch J, Campanella Bracken C. Content analysis in mass communication. Hum Comm Res. 2002;28:587–604. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxwell JA. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. [Google Scholar]