Abstract

This article illustrates common patient and provider concerns about donating tissue for the purpose of research, discusses best practices, and provides answers to common patient questions.

Introduction

Research with biospecimens is essential for advancing knowledge regarding cancer at the molecular level and will ultimately lead to an increased number of treatment options, and likely, increased survival for patients with cancer. The only way this field can progress is through the generosity of individuals who donate their specimens for research purposes and the dedication of research teams to incorporating the use of biospecimens as standard practice within clinical trials. More trials are incorporating the requirement for collection of biospecimens, and good communication and understanding are necessary for both patients and providers to make biospecimen research successful. This article, part of the series on attributes of exemplary clinical trial sites,1 uses a vignette format to illustrate common patient and provider concerns about donating tissue for the purpose of research. The article discusses best practices and provides answers to common patient questions. Mutual understanding of why biospecimen research is important and what it entails is necessary for both patients and providers to make informed decisions.

Vignette

Patient Perspective

Kathy, a vice president of a local bank, is 55 years old and has been diagnosed with locally advanced, triple-negative breast cancer. She is very scared and has heard that her probability of survival is shorter than most other patients with breast cancer. She has three adult children, two daughters and a son. One of the girls is pregnant with her first child. The other two children are in college and graduate school. Not only does she have many bills to pay, she keeps thinking about the milestones she wants to reach.

Her primary concern is finding the best treatment that will give her the time to reach her goals and keep the disease from getting worse. Second, she is concerned about her family, especially her husband Bob, who is considering a potential promotion that will mean more travel and longer hours at work. Third, Kathy is worried about whether the adverse effects of the treatment she will receive will affect her ability to function, continue working, and enjoy the life she has left to live.

She and her husband are meeting this afternoon with her oncologist to better understand her treatment options. She feels so sad and overwhelmed. She hopes her oncologist has clear and conclusive information about treatment options so that the decisions about treatment will be more straightforward.

Provider Perspective

I have just seen my two o'clock new patient. She is a 55-year-old woman who has just been diagnosed with triple-negative, locally advanced breast cancer. I know this is a setting in which the overall prognosis suggests she will have a high chance of recurrence with metastatic disease at some point in the future. I also know that the treatments we currently have for triple-negative breast cancer are inadequate, and we need better agents for our patients. I have a clinical trial with a promising new targeted agent in combination with standard therapy that I think would be a great option for her. However, to better understand how this agent is working, she would be required to provide a pathology specimen from her diagnosis, as well as pretreatment tumor biopsy, submission of a sample of her operative specimen once she undergoes surgery, and several sets of blood biomarkers.

My patient is already facing so many stressors, having just been diagnosed with a difficult cancer, and she is coming to terms with having to receive preoperative treatment and then a mastectomy. Now I am going to discuss being on a clinical trial, and, in addition, this trial is going to include a significant number of extra tests, including extra biopsies. How do I explain to her why this is important and what all these tests will mean to her? And my next new patient is waiting in the room next door.

Discussion

The preceding vignette illustrates a scenario commonly faced by patients and providers. The provider knows that the patient is eligible for a promising clinical trial, but with all of the other stressors she is facing, how will she react when the physician presents this option? Will the patient feel overwhelmed when the physician explains that participation on the clinical trial requires submission of several biospecimens? Although every situation is different, there is a growing body of evidence that can help providers prepare for these scenarios, and which provides insight into patient attitudes toward biospecimen research.

Patients Are Likely to Donate Tissue If Asked

Patients are generally receptive about donating their tissue for the purpose of research. Data published by the Eastern Cooperative Group (ECOG) found an average consent rate of 88% when an optional request for biologic specimens was made to 30,496 patients participating on an ECOG trial between November 2000 and August 2008. The consent rate varied by disease type and ranged from 63% to 93.8%, depending on the specific population.2 Populations that most frequently consented to having their specimens banked for research purposes included individuals with leukemia (93.8%), breast cancer (93.5%), and gastrointestinal cancer (91%). Populations that consented least frequently included individuals with thoracic cancer (75.7%) and multiple myeloma (75%), as well as those participating in prevention trials (63%).

There are also data suggesting that patients who are not otherwise participating on a clinical trial are often willing to donate their tissue for research purposes. In a 2003 study, investigators found that, of 3,140 surgical patients who were approached regarding donation of surplus tissue for the purpose of commercial research, only 1.2% declined.3 Reasons for not consenting included fear that anonymity would not be upheld, perceived lack of time to make the decision, spiritual beliefs, fear of compromising the diagnosis, and patient anxiety/depression. Similarly, an abstract published at the 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting reported data from a survey completed by employees at 12 cancer research sites. An average of 80% of patients at these sites are approached about donating specimens, and only 20% decline.4 These data are an important reminder that consent rates are typically high if patients are made aware of the opportunity to donate tissue for the purpose of research.

Communication Between Patient and Provider Is Essential

There is a growing body of knowledge related to the importance of provider communication to a patient's decision to participate in research. Albrecht et al found that “… patients were more likely to accrue to cancer clinical trials when their physician verbally presented items normally included in an informed consent document and when their physicians communicated in a reflective, patient-centered, supportive, and responsive manner.”5(p3324) Specific behaviors associated with patient enrollment included discussing the risks and benefits of the study, addressing patient concerns, and offering resources to help manage patient concerns. Subsequent work by Albrecht et al found that the quality and quantity of patient-physician communication affect the patient's decision-making process. Specific physician behaviors associated with decision making include building an alliance, providing support, and explaining medical content in a manner that is comprehendible to the patient and their family.6 Although the work by Albrecht et al specifically focused on communication and a patient's decision to participate in therapeutic clinical trials, these evidence-based approaches are also informative for providers who want to improve their communication with patients about donating tissue for research.

Providers should be mindful of terminology they and their staff use to explain research with specimen requirements. For example, patients may not be familiar with words like “biospecimen” or “genetic material.” Use of unfamiliar words may confuse the patient or cause increased concern that could have been prevented if more familiar wording were used. Some words can also have negative connotations for patients. For example, many patients dislike the word “biopsy” because they associate it with testing for cancer; providers should use “tissue sample” instead.7 It is always important to clearly explain medical terminology and encourage the patient to ask questions. Consistent wording should be used among physicians, nurses, and research associates at the research site. Verbal use of terminology should also be consistent with the language in the informed consent document. It can become understandably confusing to a patient (and even within the research team) when different terms are used to describe the same concept.

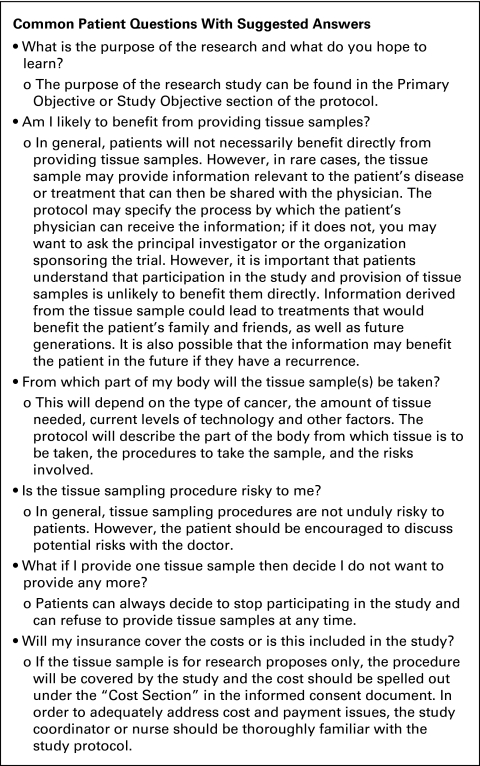

Investigators and research staff should also be prepared to answer patient questions. The Research Advocacy Network developed an information packet that provides investigators with answers to questions patients commonly ask about providing tissue samples for research.8 Selected questions from this packet are provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sample questions and answers about donation of biospecimens. From “How You Can Help Advance Cancer Research: Providing Tissue Samples as Part of a Clinical Trial,” a packet offered by the Research Advocacy Network. For more information and to download free patient and provider resources regarding research with biospecimens, please visit www.researchadvocacy.org.

Increased Patient Information About the Use of Their Specimens Does Not Reduce Participation

Another common concern is that the more intensive consent forms required for biospecimen trials may deter patients from donating their tissue for research. However, data published by ECOG have shown that the use of a more detailed consent form actually resulted in increased participation. ECOG requires patients to consent to the storage and research use of their excess tissue collected in the context of participation in therapeutic clinical trials. In a study published in 2002, investigators compared consent rates for a standard consent form and a more detailed consent form that asked patients to agree or disagree separately to each of the following three statements: (1) My tissue may be kept for use in research to learn, prevent, treat, or cure cancer; (2) My tissue may be kept for research about other health problems (for example, cause of diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, and heart disease); (3) My doctor (or someone from ECOG) may contact me in the future to ask me to take part in more research.

The investigators found that consent was actually higher when the more detailed consent form was used (93.7% assent rate) than when the original form was used (89.4% assent rate).9 These data indicate that use of a consent form that provides patients with increased control over the use of their specimens does not negatively affect patient decisions to donate specimens for the purpose of research.

Additional Practices That Can Be Implemented in Your Clinic

There are many practices that sites can implement to increase patient awareness about donating specimens for research and participating in clinical trials. The following are examples of such practices.

Conduct multidisciplinary team meetings.

Conducting team meetings may be a way to increase patient participation in clinical research. Investigators evaluating the impact of multidisciplinary team meetings on patient accrual to clinical trials discovered that 65% of eligible patients who were recommended by the team for participation ultimately consented, versus only 49% of eligible individuals who were not recommended.10 The investigators reported that the accrual rate likely was higher because team meetings helped identify potentially eligible patients and served as a reminder to discuss research options with these patients.

Team meetings should include all members of the research team: investigators, nurses, research associates, patient navigators, and patient advocates. Meeting with all members of the team will help ensure consensus and serve as an opportunity to educate the team about specific research topics, including research with biospecimens. Specific topics of discussion might include what pathways are being targeted by the investigational agent(s), specific requirements associated with collecting and processing biospecimens, and strategies for talking with patients about biospecimen research. Not only will team meetings help promote staff awareness and support, but the discussions will also help team members feel more competent when educating other colleagues and patients.

Display research-related posters where patients can see them.

Some investigators make a practice of hanging posters about research on their clinic walls. Many sites display the popular “ask me about clinical trials” posters developed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Such posters can serve as an important conversation starter and help articulate the site's clinical research culture. NCI-developed posters and buttons can be ordered at no cost from NCI's online publication locator (https://cissecure.nci.nih.gov/ncipubs/), using they key word search “ask me about clinical trials.”

Alternatively, some sites display posters of abstracts that were presented by investigators at research conferences. The posters show patients what was learned because of research conducted at the site and illustrate how patient participation is helping advance the field. The posters can also boost staff moral because they serve as a constant reminder that their hard work and commitment to research serve a global purpose. In addition to the posters, some sites hang banners that read, “Thank you for participating in research.”

Direct patients to credible online resources.

The Internet has become an increasingly common resource for patients seeking medical information. According to a study regarding patient attitudes about clinical trials, 87% of patients reported searching the Internet for health-related information. Among the same survey population, the Internet was cited most frequently as a source for information about clinical trials (58% of respondents). The next most common sources of information regarding clinical trials were health care professionals (55% of respondents), other patients (20% of respondents), and other media (20% of respondents).11 Directing patients to credible resources can help ensure they are obtaining factual information.

Have informational resources immediately available to patients.

Providing print resources to patients helps reinforce the teaching done by the research team. Such resources can also be taken home and shared with family who may not have been present during the initial discussion. Helpful patient resources are available on the Web sites of the NCI and Research Advocacy Network. Also be sure to provide the patient with the name and phone number of someone at the research site who can answer any questions that arise.

Resources for Credible Patient Information.

The “Patient Corner” on NCI's Office of Biorepositories and Biospecimen Research (OBBR) Web site:www.biospecimens.cancer.gov/patientcorner

The Research Advocacy Network Web site: www.researchadvocacy.org

The clinical trials section on Cancer.Net, ASCO's patient education Web site: www.cancer.net/clinicaltrials

A provider can greatly influence patient decision making regarding participation in clinical research. As discussed, the majority of patients are willing to donate tissue for research even if they are not otherwise participating in a clinical trial. This article illustrates common patient and provider concerns and discusses practices that can improve patients' awareness regarding the opportunity to participate in research.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Allison R. Baer, Mary Lou Smith, Johanna C. Bendell

Administrative support: Allison R. Baer

Data analysis and interpretation: Allison R. Baer, Mary Lou Smith, Johanna C. Bendell

Manuscript writing: Allison R. Baer, Mary Lou Smith, Johanna C. Bendell

Final approval of manuscript: Allison R. Baer, Mary Lou Smith, Johanna C. Bendell

References

- 1.Zon R, Meropol NJ, Catalano RB, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement on minimum standards and exemplary attributes of clinical trial sites. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2562–2567. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenab-Wolcott J, Catalano P, Fillingham B, et al. Voluntary submission of biological specimens from cancer clinical trials: An update of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(suppl):15s. abstr 6597. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jack A, Womack C. Why surgical patients do not donate tissue for commercial research: Review of records. BMJ. 2003;327:262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7409.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank E, Burns R, Carbine N, et al. Collecting tissue for research purposes: A survey of 16 institutions in the Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium (TBCRC) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl):658s. abstr 10615. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albrecht TL, Blanchard C, Ruckdeschel JC, et al. Strategic physician communication and oncology clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3324–3332. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albrecht TL, Eggly SA, Gleason MW, et al. Influence of clinical communication on patients' decision making on participation in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2666–2673. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Research Advocacy Network. Supporting a Patient's Decision to Enroll in a Clinical Trial: Tips and Talking Points. http://www.researchadvocacy.org/index.php?/research-engagement/biospecimens-biorepositories/

- 8.Research Advocacy Network. How You Can Help Advance Cancer Research: Providing Tissue Samples as Part of a Clinical Trial. Tip Sheet. http://www.researchadvocacy.org/index.php?/research-engagement/biospecimens-biorepositories/

- 9.Malone T, Catalano PJ, O'Dwyer PJ, et al. High rate of consent to bank biologic samples for future research: The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group experience. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:769–771. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.10.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNair AG, Choh CT, Metcalfe C, et al. Maximising recruitment into randomised controlled trials: The role of multidisciplinary cancer teams. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2623–2626. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolinsky CM, Wei SJ, Hampshire MK, et al. Breast cancer patients' attitudes toward clinical trials in the radiation oncology clinic versus those searching for trial information on the Internet. Breast J. 2006;12:324–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]