Abstract

Infants can imitate a novel action sequence from television and picture books; yet there has been no direct comparison of infants’ imitation from the two types of media. Varying the narrative cues available during the demonstration and test, we measured 18- and 24-month-olds’ imitation from television and picture books. Infants imitated from both media types when full narrative cues (Experiment 1; N = 76) or empty, meaningless narration (Experiment 2; N = 135) accompanied the demonstrations, but they imitated more from television than books. In Experiment 3 (N = 27), infants imitated from a book based on narration alone, without the presence of pictures. These results are discussed in relation to age-related changes in cognitive flexibility and infants’ emerging symbolic understanding.

The deferred imitation procedure was originally featured in Piaget’s theories of cognitive development. In the 1980’s, Meltzoff (1985, 1988a) operationalized the procedure to study learning and memory development. Subsequently, the imitation paradigm has been widely used to document the development of memory by pre- and early-verbal children (for reviews see Hayne, 2004; Hayne & Simcock, 2009). These studies have shown that infants and toddlers readily learn and reproduce novel action sequences demonstrated by an adult (Barr, Dowden & Hayne, 1996; Bauer & Dow, 1994; Hayne, Boniface & Barr, 2000; Herbert & Hayne, 2000a; Meltzoff, 1985), peer (Hanna & Meltzoff, 1993), or sibling (Barr & Hayne, 2003).

More recently, studies using the deferred imitation paradigm have shown that young children can copy novel action sequences from media-based presentations, such as television (Barr & Hayne, 1999; Barr, Muentener & Garcia, 2007; Barr, Muentener, Garcia, Fujimoto & Chavea, 2007; Barr, Shuck, Salerno, Atkinson & Linebarger, 2010; Barr & Wyss, 2008; Hayne, Herbert & Simcock, 2003; Meltzoff, 1988b; Strouse & Troseth, 2008), touch screens (Zack, Barr, Gerhardstein, Dickerson, & Melzoff, 2009), and picture books (Simcock & DeLoache, 2006, 2008; Simcock & Dooley, 2007). In these studies, children who are shown how to construct a novel toy via a media-based demonstration are more likely to copy the depicted actions than are age-matched participants who never saw the demonstration but were given the test objects to manipulate. These findings are consistent with recent studies using alternate methods that demonstrate that infants can relate novel information to corresponding real-world objects when the information is provided via pictures (DeLoache & Burns, 1994; Ganea, Allen, Butler, Carey & DeLoache, 2009; Ganea, Bloom-Pickard & DeLoache, 2008; Preissler & Carey, 2004; Suddendorf, 2003) or television (Decampo & Hudson, 2005; Krcmar, Grela, & Lin, 2007; Troseth, 2003a; Troseth & DeLoache, 1998; Troseth, Saylor & Archer, 2006).

Understanding what young children can learn from television and books, and whether there are any differences in learning between the media types, is important given the rapid increase in infant exposure to media in recent decades. Large-scale parental surveys have indicated that media is a prevalent part of most Western children’s daily lives starting very early in development. Reports indicate that approximately 70% of young children watch around one hour of television and video daily and that 80% are read to for around 30 minutes each day (Rideout & Hamel, 2006). Clearly, from infancy onwards, both television and books feature heavily in young children’s everyday lives.

Despite a long-standing interest in the developmental outcomes of picture-book reading and television viewing by preschoolers (3 years and over), research using the imitation paradigm has only recently begun to systematically explore what infants (2 years and younger) learn from these activities, and no studies have examined whether learning is similar across media types. To date, methodological differences in studies exploring imitation from books and television have made it difficult to directly compare the findings between media types.

One major procedural difference between book and television imitation studies has been the presence of adult narration during the demonstration. For example, empty narration, consisting of meaningless comments (e.g., “wow, look at that” and “what else can we do?”) has usually accompanied televised demonstrations and no verbal prompt (e.g., “what can you do with these things?”) has been provided at the test (Barr & Hayne, 1999; Barr et al, 2007; Hayne, et al, 2003; Meltzoff, 1988a). In contrast, full narration, consisting of meaningful comments (e.g., “we can use these things to make a rattle” and “put the ball into the jar”) has typically accompanied picture-book demonstrations and a verbal prompt (e.g., “you can use these things to make a rattle. Show me how to make a rattle”) has been provided at the test (Simcock & DeLoache, 2006; 2008).

Understanding the role of narration in learning from media is critical given that the purpose of reading children’s books or watching children’s television is often to teach new vocabulary ( Krcmar et al., 2007; Linebarger & Walker, 2005; Neuman, 1999; Rice, Huston, Truglio & Wright, 1990; Robb, Richert & Wartella, 2009; Senechal & LeFevre, 2002). The presence of narration impacts infants’ imitation from a live model by increasing long-term retention and generalization to novel test objects (Bauer, Herstgaard, Dropik, & Daly, 1988; Bauer, Wenner, Dropik, & Wewerka, 2000; Hayne & Herbert, 2004; Herbert & Hayne, 2000b). Barr and Wyss (2008) recently showed that labels accompanying a televised demonstration improve infants’ imitative performance on a difficult task relative to a demonstration without labels.

Another difference between book and television studies that may impact children’s imitative performance is the quality of the image during the demonstration. No doubt the televised and depicted images vary somewhat from study to study in terms of resolution, clarity, contrast, and color. Images of inferior quality are hypothesized to affect infants’ ability to encode the target information by increasing cognitive load (Schmitt & Anderson, 2003), possibly causing a decrease in performance relative to a high-quality image.

Finally, differences in exposure to the demonstration may affect imitative performance. Television studies usually use three demonstrations of the action sequence compared to two demonstrations used in picture book studies. Studies have found that doubling the number of demonstrations improves imitation from television (Barr et al., 2007) and books (Simcock & DeLoache, 2008). Moreover, Strouse and Troseth (2008) showed that infants imitate more from longer televised demonstrations, even with reduced repetitions. Demonstration times vary between and within media types, with book demonstrations averaging 1½ minutes (Simcock & Dooley, 2007) and television demonstrations ranging from one minute (Barr & Wyss, 2008) to 2½ minutes (Strouse & Troseth, 2008).

The purpose of the present research was to directly compare 18- and 24-month-olds’ imitation from picture books and television, controlling for prior differences in studies using each media type. The quality of the image and duration of the demonstration were controlled for by professionally producing the book and video simultaneously to ensure that they were equated for color, contrast, clarity, overall length, and the number of demonstrations. The primary goal of the experiments was to assess the effect of narrative cues on infants’ imitative performance by comparing imitation from television and picture books when full (Experiment 1) or empty narration (Experiment 2) was used during the demonstration and by varying whether a test prompt was provided during the test (Experiment 2). Further, imitation from a book was assessed when the pictures were covered and the infants received narrative cues only (Experiment 3).

EXPERIMENT 1

To date, studies examining infants’ imitation from television (TV) have exclusively used empty narration during the demonstration and no test prompt. In contrast, picture book studies have used full narration during the demonstration and a test prompt, making it difficult to directly compare imitation from books and TV. The purpose of Experiment 1 was thus to compare 18- and 24-month-olds’ imitation from TV and books when all participants were given full narrative cues during the demonstration and a test prompt (i.e., the verbal cue at retrieval).

Method

Participants

The final sample included 76 typically developing, full-term infants: 36 girls and 40 boys. There were 35 24-months-olds (M = 24.51 months, SD = .69) and 41 18-month-olds (M = 18.31 months, SD = .33). The infants were recruited from suburban areas surrounding major universities in Washington, DC, USA (US; n = 23) and Brisbane, QLD, Australia (AU; n = 53). Parents with infants of the target age were contacted via letter from existing participant databases or commercial mailing lists and were invited to participate in the study for a small gift. The majority of the infants were Caucasians from middle- to upper-class, well educated families and all had English as their first language.

Infants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: TV full narration (n = 28), book full narration (n = 25), or baseline + prompt (n = 23). Four additional infants were excluded from the final sample due to equipment failure (n = 1), experimenter error (n = 1) or overly fussy behavior (n = 2).

A pooled baseline was created using a partial replication approach to achieve n = 18 at each age (see Barr, Wyss & Somanader, 2009). An additional 13 participants (5 girls and 7 boys) were included in the baseline group from Simcock and Dooley (2007), who used the same test stimuli and methods. There were 9 24-month-olds (M = 25.19 months, SD = .19) and 4 18-month-olds (M = 18.17 months, SD = .46). The recruitment methods and demographics of the sample were the same as those for the participants in the current experiment.

Apparatus

Rattle stimuli

There were two sets of stimuli used to assemble a toy rattle (red and green versions) in a novel three-step sequence, each of which had the same three target actions: 1) push the ball into the jar; 2) attach the stick to the jar; 3) shake the stick to make a noise. The red rattle consisted of a red wooden stick (14.5 cm long) with a plug on the end which fitted into a blue plastic ball with a hole in the top (4.5 cm in diameter) and a red wooden ball (2 cm in diameter). The green rattle consisted of a green stick (12.5 cm long) attached to a white plastic lid (9.5 cm in diameter) with velcro attached to the underside of the lid, a green octagonal bead (3 cm in diameter × 2.5 cm in height), and a clear plastic cup with velcro around the top (5.5 cm in diameter × 8 cm in height).

Demonstration stimuli

There were professionally produced DVDs and picture books of an experimenter demonstrating how to construct the toy rattles. The DVDs and books were designed simultaneously to maximize similarities of the demonstration from each media type. For example, both were of high resolution, color, and brightness, and depicted identical angles and shots of the experimenter. The average size of the family TV set in the USA was 86 cm; the TV set at The University of Queensland was 76 cm. The seven page book was 13.5 cm by 17.5 cm with the photo located on the right page with text typed in black below it. Each shot in the DVD corresponded to a page in the book so that the visual images were identical in both stimuli. In the DVD and book, an adult female was shown standing against a grey background at a table covered with a black cloth and the target objects on it in front of her. The shots consisted of wide-angle at the beginning (showing the torso of the female at the table with the target objects on it) and at the end (showing the torso of the experimenter holding up the constructed rattle). The middle shots showed close-ups of the stimuli on the table and the experimenter’s hands performing the three target actions. Cuts were used to transition between the wide-angle and close-up shots, and the visual angle remained straight-on for the duration of the presentation of the book and the DVD.

Stimuli with full narration included descriptions of the goal and target actions, while stimuli with empty narration used general non-label terms (adapted from Hayne & Herbert, 2004; see Table 1). For the DVD, the narration was provided by a voiceover by the female experimenter as she performed the target actions. For the book, the female experimenter read the text corresponding to the picture on each page.

Table 1.

Description of the sequence of shots on the DVD and corresponding pages in the book, along with the accompanying full and empty narration.

| DVD Shot/Book Page | Narration Type

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Empty | Full | |

| Wide angle of experimenter at table with stimuli on it. | Linda is going to make something. | Linda makes a rattle. |

| Wide angle of experimenter at table with stimuli on it. | Linda has found some things on the table. | Linda has found some things on the table. |

| Close up of the stimuli on the table. | Look at what Linda has found. She can use these things to make something. | Linda has found a ball, a jar and a stick. She can use these things to make a rattle. |

| Close up of experimenter’s hands and the stimuli. | Look at what Linda is doing! | Linda pushes the ball into the jar. |

| Close up of experimenter’s hands and the stimuli. | Do you see what Linda is doing with those things? | Linda picks the stick up and puts it on the jar. |

| Close up of experimenter’s hands and the stimuli. | Look at what Linda is doing this time – wow! | Linda shakes the stick to make a noise: shake shake. |

| Wide angle of experimenter at table holding the rattle up. | Wow! Look what Linda made! Good job Linda! | Wow! Linda made a rattle! Good job Linda! |

Procedure

The US sample was tested in their homes and the AU sample was tested in a lab play-room at the University. All infants were tested at a day and time that the caregiver had identified as an alert and playful period. At the beginning of the visit, informed consent was obtained. To build rapport, the experimenter played with the infant for 5–10 minutes prior to commencing the study.

Demonstration Session

After the warm-up, the infant was seated comfortably for the demonstration. In the TV condition, infants sat on their caregiver’s lap, approximately 80 cm from the television set such that the screen was at eye level as they watched the video; the experimenter sat nearby on the couch. In the picture book condition, infants sat on their caregiver’s lap and the experimenter sat next to them, holding the book approximately 30 cm away at the infant’s eye level as she read. The infant saw a different female experimenter model the three target actions required to construct the toy rattle in the media demonstrations. If the infant looked away during the demonstration, the caregiver or the experimenter would redirect the toddler’s attention to the TV or book by pointing and saying the infant’s name or “look”. The media demonstration was repeated twice in succession, which took approximately one minute for both the video (M = 58.93 s, SE = .30) and the book (M = 66.73 s, SE = 1.00).

Test Session

The deferred imitation test occurred ten minutes after the demonstration and was identical for all conditions (including the no-demonstration baseline control group). During the test, the infant and the experimenter were seated facing each other on the floor; the caregiver was typically seated directly behind the infant. Each infant was tested with the same rattle stimuli (red or green) seen during the demonstration. During the 60 sec test, the experimenter placed the three parts of the rattle (ball, jar, stick) within the infant’s reach and provided the infant with the test prompt: “You can use these things to make a rattle. Show me how to make a rattle.”

Language Skill and Media Exposure

The caregivers in the media demonstration conditions were asked to complete the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory: Words and Sentences (CDI), which provides a measure of children’s general productive vocabulary. Attached was a form in which caregivers were asked to estimate the average minutes per day that their infant watched TV or was read picture books.

Coding and Reliability

Looking time

The infant’s looking time towards the TV or book was coded from a video of the demonstration session. The coder timed the duration that each infant visually attended to the TV or book based on the direction of the infant’s eye gaze during the demonstration. The infant’s looking time towards the demonstration was divided by the total length of the demonstration (book reading or TV viewing) and multiplied by 100 to give looking time expressed as a percentage. A second coder, blind to the studies’ hypothesis, independently coded 30% of the video clips for each experiment. Inter-coder reliability of intraclass correlations = .86 was obtained across the three experiments.

Imitation Scores

Infants’ production of the three target actions was coded from a video of the test session. The target actions were: 1) push the ball into the jar; 2) attach the stick to the jar; 3) shake the stick to make a noise (score range = 0–3). The coder gave each infant one point for the production of each target action completed within the 60 s test phase, timed from when the infant first touched one of the test objects. As in prior imitation studies, the actions could be produced in any order. A second coder, blind to the study’s hypothesis, independently coded 30% of the videos for each experiment. Inter-coder reliability of Kappa = .88 (94%) was obtained across the three experiments.

Results and Discussion

Preliminary analyses

Preliminary analyses of variance (ANOVAs) across all three experiments indicated no main effects or interactions involving gender, testing location, or rattle type (red vs green; with the exception of Experiment 2 in which rattle type was significant). The data were therefore collapsed across these variables for further analysis (except for Experiment. 2 in which rattle was included in the analysis). In addition, we conducted three preliminary checks to ensure that infants’ imitative performance was due to the book or TV demonstration and not to their general language skill, their daily exposure to media, or their looking time during the demonstration. We also analysed the infants’ sequencing scores as a preliminary check that the pattern of results for the order in which infants imitated the target actions did not differ from the pattern of results for the total imitation scores.

CDI Language Scores

Across all three experiments, approximately two-thirds of the CDIs were completed and returned at each age (63% reported at 18 months, M percentile rank = 37th, SD = 26.46; 65% reported at 24 months, M percentile rank = 50th, SD = 30.52) for the infants in the experimental groups. A one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to assess whether infants’ language scores influenced their imitation scores across the conditions. This analysis indicated no effect of CDI vocabulary scores on imitation, and it only accounted for 3% of the variance in infants’ imitation scores, F(1, 100) = .95, p = .33, partial η2 = .01. CDI scores were not considered further.

Daily Media Exposure

Across all three experiments, approximately two-thirds of the parents reported the average minutes per day that their infant was typically exposed to picture books (59% reported; M = 53.82 minutes, SE = 3.26) and television (70% reported; M = 55.23 minutes, SE = 5.24). One-way ANCOVAs were conducted to assess whether media exposure times influenced infants’ imitation scores in the book or TV imitation conditions. This analysis indicated no effect of daily book exposure time on imitation from books; it only accounted for 1% of the variance in infants’ imitation scores, F(1, 55) = .69, p = .41, partial η2 = .01. The ANCOVA exploring the effect of daily TV exposure on imitation from TV approached significance, F(2, 41) = 3.66, p = .06, partial η2 = .08. Additional ANCOVAs indicated that the effects of daily TV exposure on infants imitation scores were not significant for Experiment 1, F(1, 23) = .61, p = .45, partial η2 = .03 but approached significance for Experiment 2, F(1, 17) = 3.94, p = .06, partial η2 = .19. Daily media exposure times were not considered further.

Demonstration Looking Times

Infants’ looking time towards the book or TV during the demonstration was coded across the three experiments. Overall, the infants were very attentive to the demonstration (M = 90.00%, SE = 1.78). A one-way ANCOVA was conducted to assess whether infants’ attention to the demonstration was associated with their imitation scores across the conditions. This analysis indicated that there was no effect of infants’ attention to the media demonstration on their ability to imitate the target actions, and attention accounted for less than 2% of the variance in infants’ imitation scores, F(1, 161) = 2.45, p = .12, partial η2 = .02. Looking times were not considered further.

Sequencing Scores

To assess whether the infants produced the target actions in the correct order, their sequencing scores were calculated (see Table 2). Infants were given 1 point for producing pairs of target actions (i.e., target actions 1–2 and 2–3; score range = 0–2). For the three experiments the overall pattern of sequencing scores was very similar to the imitation scores (described below). A 2(age) × 3(condition) analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on sequence scores for Experiments 1 and 2. In both experiments, the age × condition interactions were significant (Exp 1: F(2, 82) = 4.37, p < .05; Exp 2: F(2, 132) = 6.95, p < .001). These interactions were explored with one-way ANOVAs across condition at each age with follow-up Student-Newman-Keuls tests (SNK; p < .05). At 24 months, the book and TV sequence scores exceeded baseline, Exp 1: F(2, 44) = 19.88, p < .001; Exp 2: F(2, 70) = 25.04, p < .001). However, at 18 months the TV sequence score exceeded baseline, but the book sequence score did not, Exp 1: F(2, 44) = 4.52, p < .05; Exp 2: F(2, 68) = 4.22, p < .05). This finding illustrates that, although 18-month-olds imitated significantly above baseline, their sequencing of the task from the book was not perfect. It is important to note, however, that this analysis provides confirmatory analysis for the target action scores that are reported throughout the paper. In the interests of length, sequencing scores were not considered further.

Table 2.

Sequencing scores (±SE) as a function of experiment, age, and demonstration condition.

| Book | Television | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1

| |||

| 18 months | .38 (.14) | .62 (.16)* | .06 (.13) |

| 24 months | .50 (.16)* | 1.50 (.15)* | .17 (.13) |

|

| |||

| Experiment 2

| |||

| 18 months | .23 (.17) | .49 (.16) | .17 (.23) |

| 24 months | .54 (.17)* | 1.43 (.16)* | .17 (.23) |

denotes that the group performed significantly above baseline

Imitation Scores

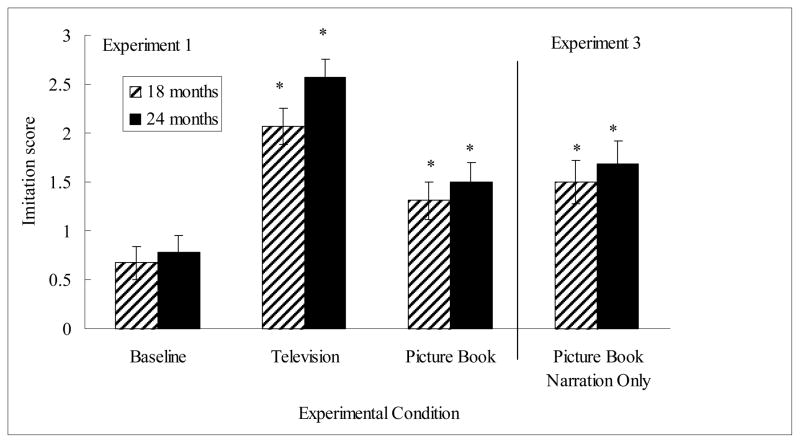

Infants’ mean imitation scores from Experiment 1 are shown in Figure 1 (left panel). These data were subjected to a 2 (age) × 3 (condition: book, TV, baseline) ANOVA. This analysis yielded a significant main effect of condition, F(2, 83) = 40.54, p < .001, partial η2 = .49. A SNK (p < .05) post-hoc test yielded three important findings. First, the infants in the baseline condition received the test prompt yet their scores were very low, indicating that infants will not spontaneously construct the rattle even when given a prompt to do so. Second, the infants in the TV (M = 2.32, SE = .13) and book conditions (M = 1.40, SE = .14) performed above baseline (M = .72, SE = .12), showing that infants successfully imitated regardless of media type. Finally, the imitative performance of the infants in the TV condition was greater than that of infants in the book conditions, indicating that infants found it easier to imitate the target actions from a TV demonstration than a book demonstration.

Figure 1.

Infants’ mean imitation scores (max = 3) as a function of condition and age in Experiment 1 (left panel) and Experiment 3 (right panel) when given full narration during the demonstration and a verbal prompt at the test. An asterisk indicates that the performance of that group is significantly greater than the age-matched baseline group.

The advantage in imitation from TV over books fits with Hayne’s (2004) representational flexibility hypothesis. That is, there is an age-related increase in infants’ ability to encode attributes of an event and subsequently retrieve the necessary target information, even under conditions that differ at encoding and retrieval. For example, although young infants fail a deferred imitation task when shown a mouse puppet at encoding but shown a rabbit puppet at test, older infants pass this task (Hayne, McDonald & Barr, 1997). By its very nature, TV has more encoding cues available (e.g., motion and sound) and has more attributes in common with the real 3-D test objects than a static picture, facilitating the development of a richer memory representation than is possible based on the cues provided in a book. Thus, when given the target objects and asked to “make a rattle”, the infants in the TV condition had a more elaborate memory from which to retrieve the target information than did the infants in the book condition.

There was no significant main effect of age, F(1, 83) = 3.14, p = .08, and age did not enter into any interactions. This differs from a number of studies showing that older infants imitate more than younger infants from media-based demonstrations (Barr et al., 2007; Hayne et al., 2003; Simcock & DeLoache, 2006, 2008). It is important to note, however, that consistent to prior research, there was a trend for 18-month-olds to perform fewer actions than 24-month-olds. It is possible that the full narrative cues at the demonstration and the test prompt may have provided optimal encoding and retrieval conditions for the younger infants and facilitated their imitative performance. The 18-month-old infants, with limited verbal skills themselves, benefited from the experimenter’s language cues to the point that they performed as well as the 24-month-olds. The notion that full narration at encoding and the test prompt improved infants’ performance was tested in Experiment 2 by removing the narrative cues available at encoding and/or retrieval and providing the infants with empty narration instead.

EXPERIMENT 2

In Experiment 1, the infants were provided with full verbal cues during the demonstration and the test phase, and they exhibited imitation from books and TV. The purpose of Experiment 2 was to assess infants’ imitation from media when no narrative cues were provided during the demonstration; the infants in Experiment 2 were provided with empty, meaningless narration. This will be the first time infants’ imitation from picture books without narrative cues will be assessed. The role of the test prompt was also examined. Half of the participants were tested with the same verbal prompt that was used in Experiment 1 (“Show me how to make a rattle”) and the other half were tested with a nonspecific prompt during the test (“Show me how to make something”).

Method

Participants

The final sample included 135 participants: 83 boys and 52 girls. There were 64 24-months-olds (M = 24.51 months, SD = .46) and 71 18-month-olds (M = 18.30 months, SD = .41). The recruitment methods and participant characteristics were the same as in Experiment 1. However, a portion of the data was also collected in New Zealand (NZ) from a sample consisting of participants from a similar demographic as the rest of the sample. There were 71 participants located in areas surrounding Georgetown University, 53 from areas around The University of Queensland, and 11 from suburbs around the University of Otago, NZ.

The infants were randomly assigned to one of five conditions: TV + prompt (n = 24), book + prompt (n = 25), TV + no prompt (n = 25), book + no prompt (n = 25), and baseline + no prompt (n = 13). For comparison purposes, the baseline + prompt (n = 23) group used in Experiment 1 was also included in the data analysis.

As in Experiment 1, an additional 24 baseline participants (10 girls and 14 boys) were included from prior published research using the same rattle stimuli to make a pooled baseline of n = 18 per group (from Barr et al., 2007 and Barr & Wyss, 2008). There were 12 24-month-olds and 12 18-month-olds. The recruitment methods and demographics of the sample were the same as those for the participants in the current experiment.

Apparatus

The same rattle sets, DVDs, and picture books used in Experiment 1 were used in Experiment 2.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to that used in Experiment 1. However, during the TV or book demonstration, all infants received empty narration (e.g., “Look at that” and “Wow, that looks interesting”). Further, during the test, half the infants were given the verbal test prompt: “You can use these things to make a rattle. Show me how to make a rattle.” and half the infants we given an empty test prompt: “You can use these things to make something. Show me how to make something.”

Results and Discussion

Imitation Scores

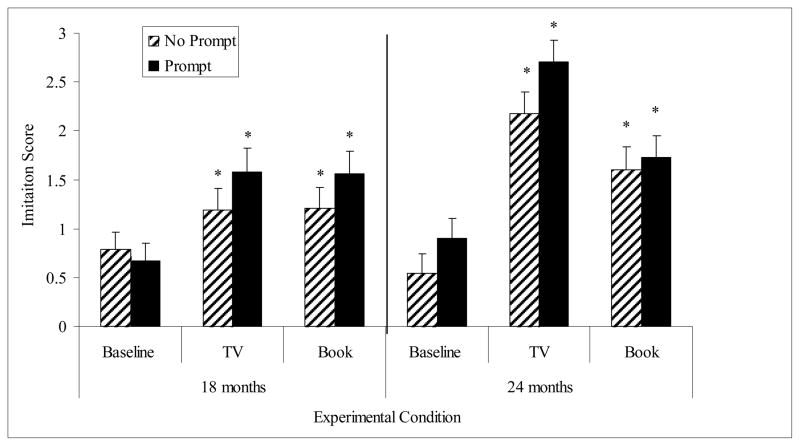

Infants’ mean imitation scores are shown in Figure 2. These data were subjected to a 2 (age) × 3 (condition: book, TV, baseline) × 2 (prompt, no prompt) × 2 (stimuli: red rattle, green rattle) ANOVA. There was a significant main effect of age, F(1, 148) = 13.53, p < .001, partial η2 = .08 and condition, F(2, 148) = 34.95, p < .001. These main effects were qualified by a significant condition × age interaction, F(2, 148) = 6.42, p < .005, partial η2 = .08.

Figure 2.

Infants’ mean imitation scores (max = 3) in Experiment 2 as a function of condition, test prompt, and age when given empty narration during the demonstration. An asterisk indicates that the performance of that group is significantly greater than the age-matched baseline group.

The interaction was explored with one-way ANOVAs across condition at each age. There were significant condition effects at 18 (F(2, 84) = 6.03, p < .005, partial η2 = .13) and 24 months (F(2, 82) = 35.11, p < .001, partial η2 = .46). SNK analyses (p < .05) showed that both age groups out-performed their age-matched baseline controls. However, at 18 months there was no significant difference in imitation from TV (M = 1.38, SE = .16) versus books (M = 1.39, SE = .15); whereas at 24 months, imitation from TV (M = 2.44, SE = .16) exceeded imitation from books (M = 1.66, SE = .16). This finding was supported with post-hoc one-way ANOVAs (p < .05) across age for each condition. There was no age-related difference in imitation in the baseline or book conditions, but the 24-month-olds imitated more than the 18-month-olds in the TV condition, F(1, 49) = 21.53, p < .005, partial η2 = .31. This age-related change in imitation from TV is likely due to older infants’ ability to make better use of the wider range of encoding cues (e.g., motion, sound) that were available from the TV demonstration in comparison to the book, particularly when few or no narrative cues were available. In contrast, without the additional provision of the experimenter’s verbal cues to facilitate encoding and retrieval, the 18-month-olds’ imitative performance was poorer relative to the 24-month-olds’ performance.

The analysis also yielded a significant main effect of test prompt, F(1, 148) = 5.46, p < .05, partial η2 = .04. Infants who received the test prompt (“Show me how to make a rattle”) during the test (M = 1.53, SE = .09) produced more target actions than those who received the empty (M = 1.25, SE = .09) test prompt (“Show me how to make something”). This finding is consistent with Hayne and Herbert’s (2004) conclusion that narrative cues at retrieval, rather than at encoding, have a greater effect on long-term recall.

There was also an unexpected main effect of stimuli. Infants produced more target actions with the red rattle (M = 1.67, SE = .09) than with the green rattle (M = 1.11, SE = .09), F(1, 148) = 20.60, p < .001, partial η2 = .12. The significant effect of stimulus is somewhat surprising and is inconsistent with the other experiments reported here, as well as with prior research that shows no difference in infants’ performance on the red and green rattles (Barr et al., 2007; Herbert & Hayne, 2000a, 2000b; Simcock & Dooley, 2007). The fact that the stimuli were counterbalanced and did not enter into any interactions suggests that this difference in performance occurred across the experiment and was not linked to a particular age or presentation mode.

The current finding of imitation from books and TV without the addition of narration shows that infants as young as 18 months were indeed exhibiting symbolic understanding of the depictions. This is consistent with research indicating that from around 18 months, infants show nascent referential understanding of pictures (DeLoache, Pierroutsakos, Uttal, Rosengren & Gottlieb, 1998; Ganea et al., 2008, 2009; Preissler & Carey, 2004).

EXPERIMENT 3

The use of narrative cues in prior picture book studies raised the question of whether the infants used the depictions symbolically to guide their imitative behavior or whether they relied on the experimenter’s narration to guide their actions (see Simcock & DeLoache, 2006). A true demonstration of symbolic use of the pictures would be imitation from the pictures without the accompaniment of verbal cues or labels. Such a finding would indicate true referential understanding of the depiction on TV or in a book; the infants would not only have to associate the 3-D test stimuli with the 2-D media, but they would also have to use the information to guide their actions with the test objects. Given that infants exhibit imitation from picture books without requiring the experimenter’s language (Experiment 2), we next investigated whether infants also imitated when they were provided with full narrative cues but no pictures were visible.

Experiment 3 explored infants’ ability to imitate based only on verbal cues. The experimenter read infants a book with full narration, but with the pictures of the rattle covered. Comparisons were made with infants in Experiment 1 who saw the pictures and received full narration and a test prompt, as well as with age-matched baseline control infants who never saw the book but were prompted at the test.

Method

Participants

The final sample included 27 participants: 12 boys and 15 girls. There were 13 24-months-olds (M = 24.59 months, SD = .42) and 14 18-month-olds (M = 18.38 months, SD = .45). Fourteen participants were tested at The University of Queensland, seven in NZ at the University of Otago, and six at Georgetown University. Recruitment and participant characteristics were the same as in Experiment 1 and 2.

All infants were assigned to the picture book verbal-cues-only condition. For comparison purposes, two conditions from Experiment 1 were included: book full narration + prompt (n = 25) and baseline + prompt (n = 36).

Apparatus

The same rattle sets and picture books used in Experiments 1 and 2 were used again in Experiment 3. However, in the present experiment the pictures of the target objects were covered with squares of paper (to ensure that the infants still looked at the book during the demonstration). Thus, the model or her hands were still visible in the book, but the target objects and actions could not be seen.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to that used in Experiment 1. The infants were provided with full narration during the demonstration and were given the full verbal prompt at the test (“You can use these things to make a rattle. Show me how to make a rattle.”).

Results and Discussion

Imitation Scores

The infants’ imitation scores are shown in Figure 1 (right panel). A 2 (age) × 3 (condition: full narration, no pictures, baseline) ANOVA on infants’ imitation scores yielded a significant main effect of condition, F(2, 82) = 10.01, p < .001, partial η2 = .20. A post-hoc SNK test (p < .05) showed that the experimental groups exhibited imitation by out-performing the control group (M = .72, SE = .14). Further, there was no difference in imitative performance whether pictures were present (M = 1.40, SE = .16) or absent (M = 1.60, SE = .16). As shown in Figure 1 (right panel), infants imitated from the book even when no pictures were present, indicating that a visual demonstration is not necessary for imitation to occur. The infants used the adult’s narration regarding the target actions to learn what to do with the target objects in much the same way that young infants can respond to another person’s verbal references about absent objects (Ganea, 2005; Ganea, Shutts, Spelke, & DeLoache, 2007; Saylor, 2004).

As in Experiment 1, there was no main effect of age and no interaction effect. When the infants received full narrative cues at the demonstration and a test prompt, the 18-month-olds performed as well as the 24-month-olds. Regardless of whether or not additional visual cues were present, the adult’s narration facilitated the young infants’ imitative performance.

General Discussion

The research reported here provides an important contribution to the imitation literature by (1) directly comparing learning a novel action sequence from books and TV during infancy and (2) examining the role of narrative cues on imitation from TV and picture books. This comparison was precluded in the past due to methodological differences between studies using each media type. After controlling for these differences, we examined the effect of an experimenter’s narrative cues on 18- and 24-month-olds’ imitation from books and television. We found that infants imitated elements of a novel action sequence from TV and books when they received a full description of the event (Experiment 1) as well as when the demonstration included no meaningful narration (Experiment 2). That is, infants imitate from TV and books with no narration, showing that they have an impressive ability to take information from symbolic media and apply it to real life objects. Moreover, imitation from TV exceeded imitation from books. In Experiment 3, infants imitated from the book when provided only with adult narration and when no visual cues were available. Overall, three major findings will be discussed (1) infants imitate from both TV and picture books in the absence of full narration, (2) infants can learn from narration without the presence of pictures and (3) infants imitate an action sequence better from TV than from a book.

These results show that even before infants can speak fluently themselves, they can use another person’s verbal cues to facilitate encoding and retrieval of a target event. This is similar to findings from the Bauer (Bauer et al., 1988, 2000) and Hayne (Hayne & Herbert, 2004; Herbert & Hayne, 2000a) labs that tested infants’ imitation from a live model and suggested that the same cognitive processes are at work with information learned from media-based demonstrations. The finding that a narrative prompt at the time of the test facilitates recall, even with no narration at the demonstration (Experiment 2), also fits with Hayne and Herbert’s (2004) conclusions that, when there is a high cognitive load (such as a long delay, or in this case, a media demonstration), verbal cues at retrieval play a more important role in memory than do the verbal cues at encoding.

Furthermore, infants imitated above baseline even when verbal cues or visual cues were not provided. This finding indicates that infants can use a picture book symbolically to guide their actions with real objects. As prior picture book imitation studies have included both verbal descriptions and visual depictions (to increase ecological validity), it was unclear to what extent infants used the pictures or narration to guide their behavior. Our finding that even 18-month-olds can imitate from pictures without narration is consistent with TV imitation studies (Barr & Hayne, 1999; Barr et al., 2007; Melzoff, 1988b) and research showing that, around this age, infants also exhibit other behaviors indicative of emerging symbolic understanding: They begin to point to and label pictures (DeLoache, et al., 1998), as well as transfer labels of depicted objects to the corresponding real objects (Ganea, et al., 2008; Ganea et al., 2009; Preissler & Bloom, 2007; Preissler & Carey, 2004; Vandewater, Park, Lee & Barr, in press).

Strikingly, Experiment 3 showed that infants imitated even when pictures were not visible in the book; they did so based on the experimenter’s narration alone. This discovery relates to research on infants’ understanding of another person’s reference to absent entities (Ganea, 2005; Saylor, 2004). In Ganea’s (2005) study, 14-month-olds were introduced to a stuffed toy animal that was then hidden behind a couch. When the experimenter named the toy, the infants indicated understanding of the verbal reference by looking, turning, and pointing to where the toy was hidden. In a subsequent study, when 22-month-olds were told that the hidden animal “had water spilled on it”, they correctly identified the wet toy rather than the dry toy they originally saw (Ganea et al., 2007). In the current study, the infants were never shown the components of the rattle before the test; yet they must have formed a mental representation of the event based on the experimenter’s narration (and possibly assimilated this with their prior experiences with toy rattles). The infants’ imitative performance nonetheless demonstrates an impressive ability to understand the experimenter’s references to the absent objects.

Despite controlling for differences between books and TV apparent in prior imitation studies (e.g., clarity of the image, duration of the demonstration, narrative cues), there was superior imitation of an action sequence from TV than from books by both age-groups in Experiment 1 and by the 24-month-olds in Experiment 2. This advantage occurred even though parents reported equal daily exposure to books and TV (average 1 hour of each). However, as there was a marginal relation between infants’ daily TV exposure and their imitation scores (see preliminary analyses) the TV advantage could possibly be attributed to their everyday TV exposure. We hypothesize that superior imitation of an action sequence from TV is due to additional encoding cues (e.g., motion, sound) afforded by TV that facilitates encoding of the target event, resulting in better memory performance (see also Gibbons, Anderson, Smith, Field, & Fischer, 1986). However, without the additional benefit of encoding the event with an adult’s narrative cues the 18-month-olds in Experiment 2 imitated from the book and TV at equal rates. This finding supports the notion that increasing the range of cues available at encoding and/or retrieval serves to facilitate infants’ memory performance (for reviews see Hayne 2006; Hayne & Simcock, 2009). The TV superiority finding does, however, require additional empirical attention.

Different media platforms may provide advantages for learning different types of content. In the present study, learning an event sequence from TV was more effective than learning it from a book, possibly due to the availability of action-related movement cues in the televised demonstration. Note, however, that performance depended on the availability of retrieval cues; only in some conditions did imitation approach high levels (see Figures 1 and 2). It remains open, however, as to whether different types of content (e.g., letters, numbers, colors, animals) that commonly feature in children’s media are best conveyed via books or TV. There are a number of recent studies showing that picture books are a successful teaching medium. For example, Ganea, Ma, and DeLoache (in press) demonstrated that preschoolers learn and transfer information about biological camouflage from picture books to real world situations, and research with toddlers has shown that they can learn facts from picture books (Tare, Chiong, Ganea, & DeLoache, under review). Recent findings demonstrate, however, that manipulatives such as tabs and pop-ups in books interfere with learning during early childhood (Chiong & Deloache, 2007; Tare et al., in press).

It might well be that the way that the medium is used by parents is just as important as how the information is presented (Barr, Zack, Muentener, & Garcia, 2008; Fidler, Zack, & Barr, 2010). Although there are individual differences between parents, book-reading is generally a highly scaffolded activity (e.g., Deloache & DeMendoza, 1987; Ninio, 1983). Through joint-reading interactions, infants learn the sounds of language via techniques such as rhyme and repetition (Foy & Mann, 2003) and the pre-literacy conventions of picture books: how to hold books upright, turn pages, and point to and label pictures (DeLoache, Uttal, & Pierroutsakos; 2000; Nino & Bruner, 1978). On the other hand, although high quality parent-child interactions during TV viewing can occur (Barr, et al., 2008; Fidler et al., 2010), the frequency of interactions tends to decrease relative to when the TV is off (Kirkorian, Pempek, Murphy, Schmidt, & Anderson, 2009). Coupled with the present findings, this suggests that, while quality interactions may be beneficial to infants during TV viewing, such interactions may be more common during book-reading. Future research is required regarding how to best facilitate learning from both television and book-reading during early childhood.

In summary, the present experiments are important in bridging the gap between TV and picture book imitation studies that have used different methodologies. They show that, when features of the demonstration are controlled, infants can imitate from TV and books even if only depictions and not descriptions are available. When directly comparing imitation from the media types, infants’ imitation of an event sequence from TV exceeded their performance from picture-books, showing that the wider range of retrieval cues afforded by TV facilitated imitation. Further, adding additional retrieval cues at the test with a specific verbal prompt also facilitated infants’ performance. Finally, the finding that infants can imitate from a book with only narrative cues shows an impressive ability to understand another person’s verbal references to absent objects.

Acknowledgments

Support for this paper was provided by NIH grant # HD056084 to Rachel Barr and Gabrielle Simcock. Special thanks to Natalie Brito, Paula McIntyre and Emily Atkinson for their help in the coding and collation of this data. A very special thank you to all the families who made this research possible.

Contributor Information

Kara Garrity, Email: kara.m.garrity@gmail.com.

Rachel Barr, Email: rfb5@georgetown.edu.

References

- Barr R, Dowden A, Hayne H. Developmental changes in deferred imitation by 6- to 24-month-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development. 1996;19:159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Hayne H. Developmental changes in imitation from television during infancy. Child Development. 1999;70(5):1067–1081. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Hayne H. It’s not what you know, it’s who you know: Older siblings facilitate imitation during infancy. International Journal of Early Years Education. 2003;11:7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Muentener P, Garcia A. Age-related changes in deferred imitation from television by 6- to 18-month-olds. Developmental Science. 2007;10:910–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Muentener P, Garcia A, Fujimoto M, Chavez V. The effect of repetition on imitation from television during infancy. Developmental Psychobiology. 2007;49:196–207. doi: 10.1002/dev.20208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Shuck L, Salerno K, Atkinson E, Linebarger DL. Music interferes with learning from television during infancy. Infant and Child Development. 2010;19:313–331. [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Wyss N. Reenactment of televised content by 2-year-olds: Toddlers use language learned from television to solve a difficult imitation problem. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31:696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Wyss N, Somanader M. Imitation from television during infancy: The role of sound effects. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2009;123:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Zack E, Muentener P, Garcia A. Infants’ attention and responsiveness to television increases with prior exposure and parental interaction. Infancy. 2008;13:3–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PJ, Dow GA. Episodic memory in 16- and 20-month-old children: Specifics are generalized but not forgotten. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:403–417. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PJ, Hertsgaard LA, Dropik P, Daly BP. When even arbitrary order becomes important: Developments in reliable temporal sequencing of arbitrarily ordered events. Memory. 1988;6:165–198. doi: 10.1080/741942074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PJ, Wenner J, Bropik PL, Wewerka SS. Parameters of remembering and forgetting in the transition from infancy to early childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2000;65:1–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiong C, Deloache JL. Unpublished manuscript. 2007. The effect of manipulative features on young children’s learning from picture books. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decampo JA, Hudson JA. When seeing is not believing: Two-year-olds’ use of video representations to find a hidden toy. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2005;6:229–258. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoache JS, Burns NM. Early understanding of the representational function of pictures. Cognition. 1994;52(2):83–110. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLoache JS, DeMendoza OA. Joint picture book interactions of mothers and 1-year-old children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1987;5:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoache JS, Pierroutsakos SL, Uttal DH, Rosengren KS, Gottlieb A. Grasping the nature of pictures. Psychological Science. 1998;9(3):205–210. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoache JS, Uttal DH, Pierroutsakos SL. What’s up? The emergence of an orientation preference for picture books. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2000;1:81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Fidler A, Zack E, Barr R. Television Viewing Patterns in 6- to 18-month-olds: The Role of Caregiver-infant Interactional Quality. Infancy. 2010;15:176–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2009.00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy JG, Mann V. Home literacy environment and phonological awareness in preschool children: Differential effects for rhyme and phoneme awareness. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003;24:59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ganea PA. Contextual factors affect absent reference comprehension in 14-month-olds. Child Development. 2005;76:989–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganea PA, Allen ML, Butler L, Carey S, DeLoache JS. Toddlers’ referential understanding of pictures. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganea PA, Bloom-Pickard MB, DeLoache JS. Transfer between picture books and the real world by very young children. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2008;9:46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ganea PA, Ma L, DeLoache JS. Young children’s learning and transfer of biological information from picture books to real animals. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01612.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganea PA, Shutts K, Spelke ES, DeLoache JS. Thinking of things unseen. Infants’ use of language to update mental representations. Psychological Science. 2007;18:734–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons J, Anderson DR, Smith R, Field DE, Fischer C. Young children’s recall and reconstruction of audio and audiovisual narratives. Child Development. 1986;57:1014–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna E, Meltzoff A. Peer imitation by toddlers in laboratory, home, and day-care contexts: Implications for social learning and memory. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:701–710. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H. Infant memory development: Implications for childhood amnesia. Developmental Review. 2004;24:33–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H. Age-related changes in infant memory retrieval: Implications for knowledge acquisition. In: Munakata Y, Johnson MH, editors. Processes of Brain and Cognitive Development. Attention and Performance XXI. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, Boniface J, Barr R. The development of declarative memory in human infants: Age-related changes in deferred imitation. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:77–83. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, Herbert J. Verbal cues facilitate memory retrieval during infancy. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2004;89:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, Herbert J, Simcock G. Imitation from television by 24- and 30-month-olds. Developmental Science. 2003;6:254–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, McDonald S, Barr R. Developmental changes in the specificity of memory over the second year of life. Infant Behavior & Development. 1997;20:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, Simcock G. Memory development in toddlers. In: Courage ML, Cowan N, editors. The Development of Memory in Infancy and Childhood. Psychology Press; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert J, Hayne H. Memory retrieval by 18–30-month-olds: Age-related changes in representational flexibility. Developmental Psychology. 2000a;36:473–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert J, Hayne H. The ontogeny of long-term retention during the second year of life. Developmental Science. 2000b;3:50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkorian HL, Pempek TA, Murphy LA, Schmidt ME, Anderson DR. The Impact of Background Television on Parent–Child Interaction. Child Development. 2009;80:1350–1359. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krcmar M, Grela B, Lin K. Can toddlers learn vocabulary from television? An experimental approach. Media Psychology. 2007;10:41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Linebarger DL, Walker D. Infants’ and toddlers’ television viewing and language outcomes. American Behavioral Scientist. 2005;48:624–645. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff A. Immediate and deferred imitation in 14- and 24-month-old infants. Child Development. 1985;56:62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff A. Infant imitation and memory: Nine-month-olds immediate and deferred tests. Child Development. 1988a;59:217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff A. Imitation of televised models by infants. Child Development. 1988b;59:1221–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb01491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman SB. Books make a difference: A study of access to literacy. Reading Research Quarterly. 1999;34:286–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ninio A. Joint book reading as a multiple vocabulary acquisition device. Developmental Psychology. 1983;19:445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Ninio A, Bruner J. The achievement and antecedents of labeling. Journal of Child Language. 1978;5:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Preissler MA, Bloom P. Two-year-olds appreciate the dual nature of pictures. Psychological Science. 2007;18:1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preissler MA, Carey S. Do both pictures and words function as symbols for 18- and 24-month-olds children? Journal of Cognition and Development. 2004;5(2):185–212. [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Huston AC, Truglio R, Wright J. Words from:Sesame Street”: Learning vocabulary while watching. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Rideout VJ, Hamel E. The media family: Electronic media in the lives of infants, toddles, preschoolers and their parents. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robb MB, Richert RA, Wartella EA. Just a talking book? Word learning from watching baby videos. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2009;27:27–45. doi: 10.1348/026151008x320156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor MM. 12- and 16-month-old infants recognize properties of mentioned absent things. Developmental Science. 2004;7:599–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt KL, Anderson DR. Television and reality: Toddlers use of visual information from video to guide behavior. Media Psychology. 2002;4:51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Simcock G, DeLoache J. Get the Picture? The effects of iconicity on toddlers’ re-enactment from picture books. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1352–1357. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simcock G, DeLoache J. The effect of repetition on infants’ imitation from picture books varying in iconicity. Infancy. 2008;13:687–697. [Google Scholar]

- Simcock G, Dooley M. Generalization of learning from picture books to novel test conditions by 18- and 24-month-old children. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1568–1578. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strouse GA, Troseth GL. “Don’t try this at home”: Toddlers’ imitation of new skills from people on video. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2008;101:262–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suddendorf T. Early representational insight: Twenty-four-month-olds can use a photo to find an object in the world. Child Development. 2003;74(3):896–904. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tare M, Chiong C, Ganea PA, DeLoache JS. Less is More: The effect of manipulative features on children’s learning from picture books. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.06.005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troseth GL. TV Guide: Two-year-old children learn to use video as a source of information. Developmental Psychology. 2003a;39:140–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troseth GL, DeLoache JS. The medium can obscure the message: Young children’s understanding of video. Child Development. 1998;69:950–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troseth GL, Saylor MM, Archer AH. Young children’s use of video as a source of socially relevant information. Child Development. 2006;77:786–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandewater E, Park SE, Lee SJ, Barr R. Transfer of learning from video to books during toddlerhood: Matching words across context change. in press. For review for the Journal of Children and Media. [Google Scholar]

- Zack E, Barr R, Gerhardstein P, Dickerson K, Meltzoff AN. Infant imitation from television using novel touch screen technology. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2009;27:13–26. doi: 10.1348/026151008x334700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]