Abstract

Three models have been proposed to explain the imprinting of the mouse Igf2 gene on the maternal chromosome. We ruled out the importance of DNA methylation at Igf2 by showing that silencing of Igf2 accompanying the loss of DNA methylation could be overcome by a mutation at the neighboring H19 gene that activates Igf2. By replacing the H19 structural gene with a protein-coding gene, we have ruled out a role for H19 RNA in the imprinting of Igf2. This replacement resulted in sporadic activation of the H19 promoter on the paternal chromosome without affecting the level of expression of Igf2, a finding that is inconsistent with strict promoter competition between the genes. We conclude that a transcriptional model involving access to a common set of enhancers shared between Igf2 and H19 is the most likely explanation for Igf2 imprinting.

Keywords: Genomic imprinting, H19, Igf2, DNA methylation, promoter competition, chromatin

The mammalian genome harbors a small number of genes whose expression is affected by the parental origin of the chromosome, a process known as genomic imprinting (Barlow 1995; Bartolomei and Tilghman 1997). The number of imprinted genes that have been identified now numbers >20, and comparisons among these genes have begun to reveal some common features. Foremost among these is allele-specific DNA methylation, which has been implicated in the mechanism by which a cell discriminates between the two parental alleles of an imprinted gene and determines which will be transcribed (Li et al. 1993). Furthermore, imprinted genes are frequently linked within clusters that contain both maternally and paternally expressed genes (Zemel et al. 1992; Mutirangura et al. 1993; Rougeulle et al. 1997; Vu and Hoffmann 1997; Wutz et al. 1997). Finally, an unusual feature of these clusters is that they contain at least one imprinted gene that encodes an untranslated RNA (Brannan et al. 1990; Kay et al. 1993; Wevrick et al. 1994; Wutz et al. 1997).

All of these properties are evident within an ∼800-kb cluster of genes that resides on the distal end of mouse chromosome 7 (Caspary et al. 1998). This cluster contains the paternally expressed insulin-like growth factor 2 (Igf2) and insulin-2 (Ins2) genes, which are flanked on the telomeric side by the maternally expressed p57Kip2, Mash2, and Kvlqt1 genes and on the centromeric side by the maternally expressed H19 gene. Of these genes, the one whose imprinting mechanism is best understood is H19, which encodes the first of the untranslated RNAs to be shown to be imprinted (Brannan et al. 1990; Bartolomei et al. 1991). The silence of H19 on the paternal chromosome is thought to be the result of DNA methylation within the gene and its 5′ flank that is established during spermatogenesis and maintained throughout embryogenesis (Bartolomei et al. 1993; Brandeis et al. 1993; Ferguson-Smith et al. 1993; Li et al. 1993).

The absence of any DNA methylation on the silent Igf2 gene forced us to consider alternative models to explain its imprinting. In fact, it is the expressed paternal allele of Igf2 that is specifically methylated in two locations: within the gene itself and in its 5′ flank (Sasaki et al. 1992; Feil et al. 1994). Furthermore, this correlation between methylation and expression of Igf2 extends to the choroid plexus, a tissue that expresses both alleles of Igf2 and exhibits biallelic methylation (DeChiara et al. 1991; Feil et al. 1994; Svensson et al. 1995), and to mutations at H19 that activate Igf2 (Forne et al. 1997). These results, taken together with the loss of Igf2 expression in embryos deficient in DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt), led to the proposal that methylation was acting as a positive signal for transcription, possibly by inhibiting the binding of a repressor (Walter et al. 1996).

An alternative to this hypothesis was based on the very similar patterns of expression of Igf2 and H19 during development. Bartolomei and Tilghman (1992) proposed that their imprinting is linked through a competition for a common set of transcriptional enhancers. In this scenario, the silence of the maternal Igf2 gene is a consequence of its failure to compete successfully with the unmethylated H19 gene in cis. This model gained considerable support when it was demonstrated that both genes require for their expression two endoderm-specific enhancers that lie 3′ of the H19 gene (Leighton et al. 1995b). Furthermore, the insertion of an extra set of enhancers between the two genes results in the activation of the unmethylated maternal Igf2 gene (Webber et al. 1998). Finally, two targeted mutations that delete the competitor H19 gene and either 10 kb (H19Δ13) or 40 bp (H19Δ3) of its 5′ flank also result in complete or partial activation, respectively, of the maternal Igf2 gene 90 kb away (Leighton et al. 1995a; Ripoche et al. 1997).

In this report we perform an epistasis test to assess the relative importance of DNA methylation, versus the absence of the H19 region, to Igf2 expression. We conclude that the Igf2 gene does not require DNA methylation for its expression in the embryo. Furthermore, we generate a targeted replacement of the H19 structural gene to definitively show that the RNA itself plays no role in the imprinting of Igf2.

Results

Igf2 is expressed in the absence of DNA methylation in H19 mutant animals

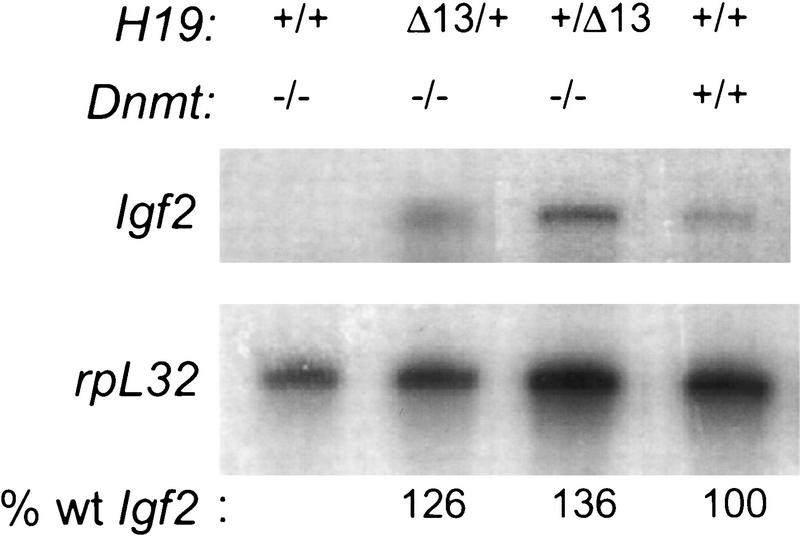

To assess the relative importance of methylation in Igf2 imprinting, we performed an epistasis test to ask whether the silencing of Igf2 by loss of DNA methylation in Dnmt−/− embryos could be overcome by the H19Δ13 mutation that activates maternal expression of Igf2. We utilized mice bearing the null DnmtS allele; homozygous mutant embryos do not survive past e10, and exhibit a marked reduction in both genome-wide and Igf2-specific methylation (Li et al. 1992, 1993; Tucker et al. 1996). Dnmt−/− embryos that had also inherited the H19Δ13 mutation on either the maternal or paternal chromosome were harvested at e9.5. DNA was prepared from yolk sacs for genotyping, and the levels of Igf2 RNA were determined by RNase protection in pooled embryos of the same genotype. As the results in Figure 1 illustrate, Igf2 expression is unaffected by the loss of DNA methylation when the H19Δ13 mutation is present. The levels of Igf2 expression in Dnmt−/−; H19Δ13/+ embryos were similar to those obtained in Dnmt+/+ littermates, on the basis of comparisons with rpL32 RNA, which served as an internal control. The levels were independent of the parental origin of the H19Δ13 mutation, as would be predicted if the loss of methylation had erased all differences between the parental chromosomes. From this observation, we conclude that the expression of Igf2 at this stage in development does not require DNA methylation, but does require the methylation or deletion of the H19 gene region.

Figure 1.

Expression of Igf2 RNA in Dnmt−/−;H19Δ13/+ double mutant embryos. Embryos were generated by crossing Dnmt+/− heterozygotes to Dnmt+/−; H19Δ13/+ double heterozygotes. Embryos were pooled according to genotype and the levels of Igf2 and rpL32 mRNAs were determined by RNase protection. The level of Igf2 RNA is expressed as a percent of that in wild-type embryos, after normalization to rpL32 RNA by PhosphorImager densitometry.

Igf2 imprinting does not require H19 RNA in cis

Although the original enhancer competition model predicted a strictly transcriptional role for the H19 gene in Igf2 imprinting, a function for the RNA product of the gene has been suggested, as both the H19Δ13 and H19Δ3 mutations that disrupted Igf2 imprinting removed both the promoter and the structural H19 gene (Leighton et al. 1995a; Ripoche et al. 1997). Moreover, the presence of untranslated RNAs in multiple imprinted regions, together with the compelling evidence that expression of an untranslated RNA encoded by the Xist gene is required for X chromosome inactivation (Penny et al. 1996; Marahrens et al. 1997), raised expectations that there might be some function for these RNAs in imprinting. Functional evidence for the importance of sequences within the H19 structural gene came from the experiments of Pfeifer et al. (1996) who observed that when the H19 structural gene was replaced with the luciferase gene within the context of a 14-kb transgene, imprinting of the transgene was lost.

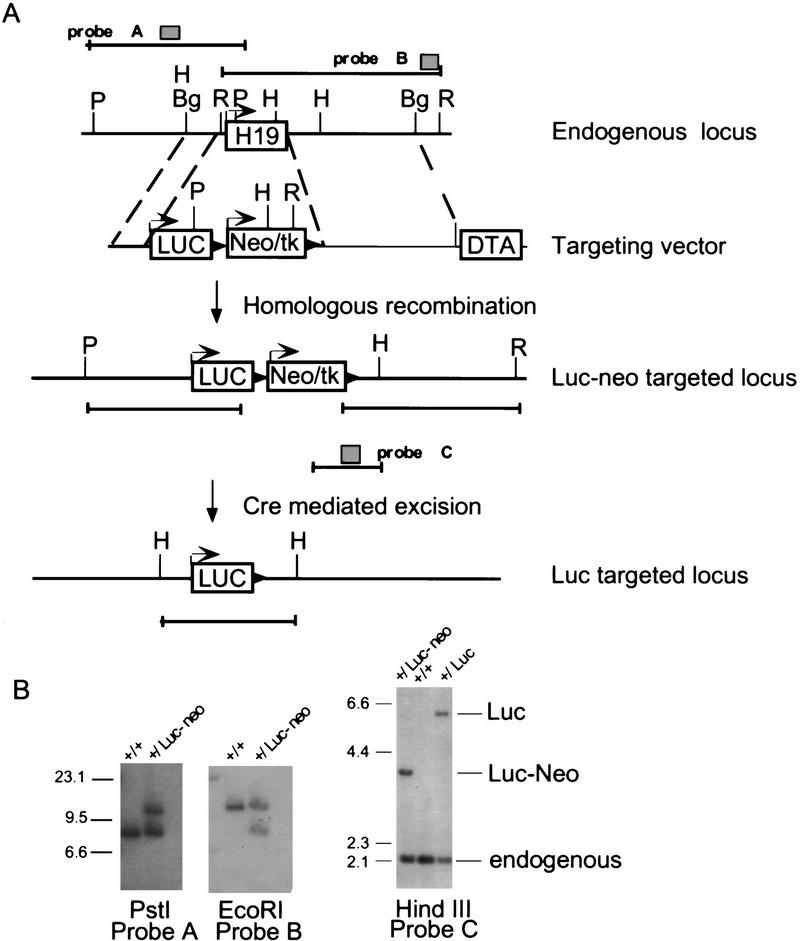

To examine the role of H19 RNA in the silencing of Igf2, a targeting strategy was devised to delete all but the first three nucleotides of the H19 transcript and replace them with a gene coding for the protein luciferase (luc) (Fig. 2). The neomycin resistance (neoR) selectable marker was flanked by loxP sites to facilitate removal by Cre-mediated homologous recombination, which would leave the targeted locus modified only within the coding region of the H19 gene (Sauer and Henderson 1989). Correctly targeted events and accurate excision of neoR were verified with probes that lie outside of the targeting vector (Fig. 2B). RNase protection analysis confirmed the absence of maternal H19 RNA (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Strategy for replacing H19 RNA with luciferase RNA. (A) Structure of the endogenous H19 locus, along with the positions and sizes of restriction fragements and radiolabeled probes (shaded boxes) used in B, are illustrated at the top. The targeting vector contains the luciferase coding region (LUC) inserted at +3 bp of the H19 structural gene, followed by the neoR gene linked to the tk gene by an internal ribosomal entry site (neoR/tk) driven by the phosphoglycerokinase promoter. The neo/tk gene is flanked by loxP sites from bacteriophage P1 (▸). The regions of homology between the targeting vector and the endogenous locus are indicated by broken lines. The vector also includes the diphtheria toxin A (DTA) chain gene for negative selection (McCarrick et al. 1993). The structure of the correctly targeted locus, before and after excision of neo/tk with Cre recombinase, are illustrated, along with the restriction fragments used to diagnose them. The position of probe C is indicated by the shaded box. (B) DNAs prepared from E14.1 wild-type cells (+/+) and a correctly targeted line before (+/Luc–Neo) and after (+/Luc) excision of Neo/tk were analyzed by digestion with restriction enzymes and hybridized to probes A–C, as indicated. The size marker was λDNA digested with HindIII. (P) PstI; (Bg) BglII; (R) EcoRI; (H) HindIII.

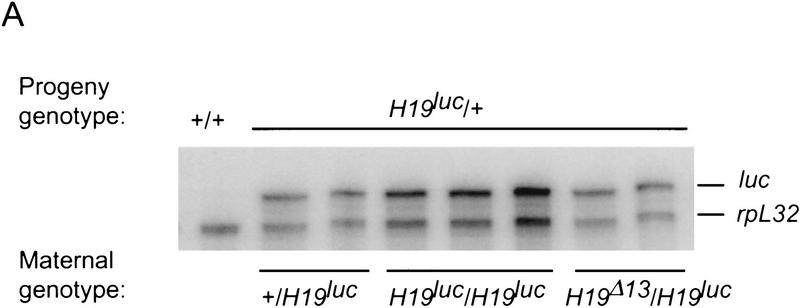

The expression of the luc gene in neonatal liver was examined by an RNase protection assay in progeny of +/H19luc mothers (Fig. 3A). Regardless of whether the mutation was on the grandmaternal or grandpaternal chromosome, the gene was expressed at equivalent levels, suggesting that resetting from a male to a female epigenetic state was occurring. Similar results were obtained in skeletal muscle (data not shown). To ask whether the maternally inherited H19luc locus was unmethylated, the 5′ flank and the luc gene were examined by digestion of genomic DNA from neonatal liver with methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes (Fig. 3B). A region encompassing from −2 to −4 kb within the 5′ flank of the gene, which is thought to contain the primary paternal gametic mark but is always unmethylated on the maternal chromosome (Tremblay et al. 1995, 1997), is equally unmethylated in maternal H19luc mice. The lack of methylation is also evident within the promoter and the luc gene itself (data not shown). These results are consistent with the findings of Ripoche et al (1997), who showed that a neoR gene inserted in place of the H19 promoter and structural gene was appropriately unmethylated and expressed on the maternal chromosome.

Figure 3.

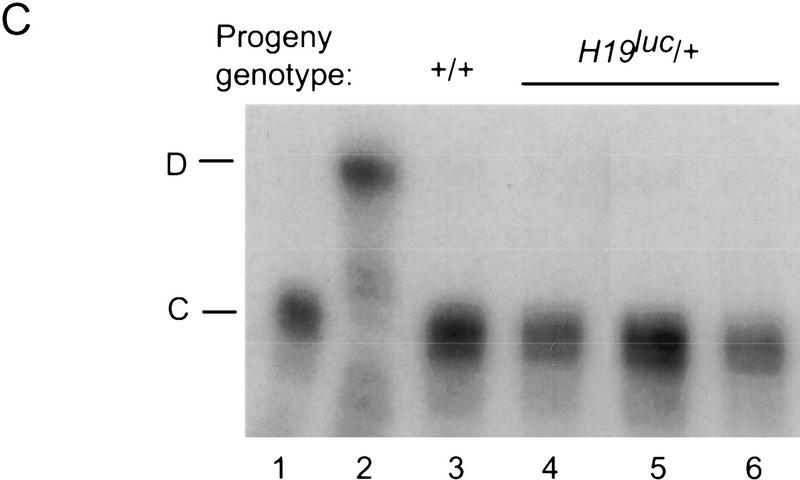

Maternal inheritance of H19luc. (A) Expression of H19luc and rpL32 were measured by RNase protection in day 4 and 5 neonatal livers of progeny of +/H19luc, H19luc/H19luc, and H19Δ13/H19luc mothers and M. castaneus (+) fathers. (B) Genomic DNA from wild type (+/+) and progeny of H19luc/+ females and M. castaneus males was digested with SacI alone (−) or SacI together with HpaII, HhaI, or MspI, as indicated. The DNA was detected with a 4-kb EcoRI hybridization probe (shaded rectangle) derived from the 5′ end of the H19 gene. The positions of the SacI (S) sites, including the polymorphic site in M. castaneus (S*) are indicated, along with the start of H19 transcription (arrow). (M) Maternal allele; (P) paternal allele. The size markers are indicated at right. (C) Igf2 RNA was assayed by an allele-specific RNase protection assay in a subset of the animals described in A as well as in M. castaneus neonatal liver (C, lane 1) and C57BL/6J liver (D, lane 2). The maternal genotypes are +/H19luc (lane 4), H19luc/H19luc (lane 5), and H19Δ13/H19luc (lane 6).

Although there is no requirement for maternal H19 RNA in the embryo, the RNA could be required in trans for setting the maternal imprint in primordial germ cells or in early germ-cell development, in which the gene has been shown to be expressed from both chromosomes (Szabo and Mann 1995). To test this, we examined transmission of a paternally inherited H19luc allele from both H19luc homozygous and H19Δ13/H19luc females. The females were crossed to wild-type males and +/H19Δ13 males so that the expression and methylation of the H19luc gene could be assessed in either the presence or absence of the paternally provided H19 gene. No differences in the expression of H19luc RNA were observed in any of these genetic combinations, providing strong evidence that there is no requirement for H19 RNA in the maternal germline for resetting or maintaining the unmethylated, transcriptionally active status of the H19luc allele (Fig. 3A and data not shown).

Having verified that replacement of H19 with luc resulted in normal maternal expression from the H19 promoter, we next examined the impact of this mutation on Igf2 imprinting. Heterozygous, homozygous, and compound heterozygous female mice bearing the H19luc allele (H19luc/+, H19luc/H19luc, and H19luc/H19Δ13) were crossed to Mus castaneus males and Igf2 expression was examined in livers and skeletal muscle from neonatal progeny by allele-specific RNase protection (Fig. 3C; data not shown). No activation of the maternal Igf2 gene was observed under any circumstance, establishing that imprinting of the Igf2 gene does not require the presence of the H19 RNA in cis. Thus, unlike the previous two mutations at H19, both of which removed the promoter and structural gene, the loss of the structural gene alone has no consequence for Igf2 imprinting.

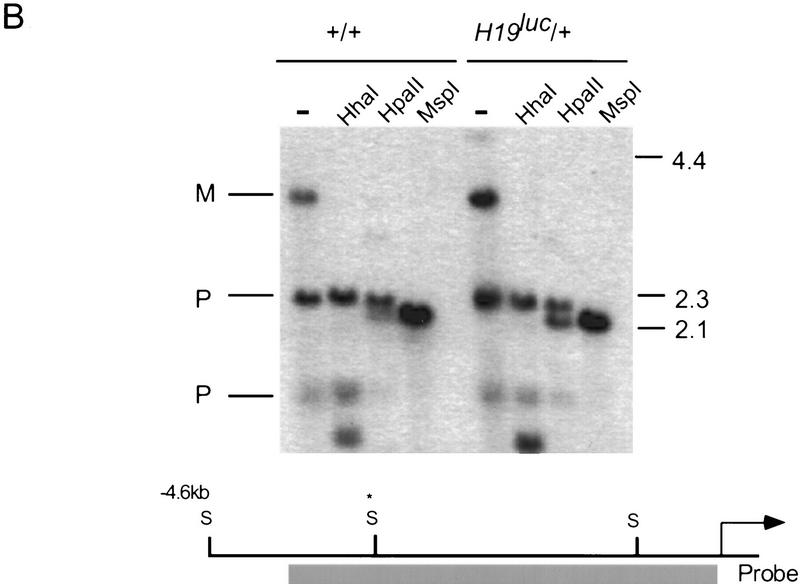

Sporadic methylation and silencing of H19luc on the paternal chromosome

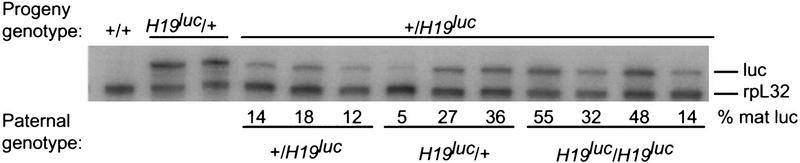

When the H19luc mutation was inherited from fathers, the level of expression of luc RNA in the progeny was surprisingly variable, suggesting that there had been sporadic relaxation of the imprint (Fig. 4). The levels varied from 5% to 55% of that measured in age-matched progeny inheriting H19luc maternally, on the basis of comparisons with the levels of rpL32 RNA for normalization. The variability could not be ascribed to the presence or absence of wild-type H19 during spermatogenesis in the father, as progeny of both H19luc homozygotes and H19luc/H19Δ13 males displayed the same degree of variability in luc imprinting as those from H19luc heterozygotes. Furthermore, the variability did not depend on the presence of H19 RNA during embryogenesis, as it occurred in both +/H19luc and H19Δ13/H19luc progeny (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of luc RNA upon paternal inheritance. Males of the genotype indicated (paternal genotype) were crossed to wild-type (+/+) females or +/H19Δ13 females and the levels of luc RNA and rpL32 RNA was determined by RNase protection assay in neonatal livers of the progeny. The levels of luc RNA, as determined by PhosphorImager densitometry and normalization to rpL32 RNA levels, are expressed as a percent of the level upon maternal inheritance (H19luc/+).

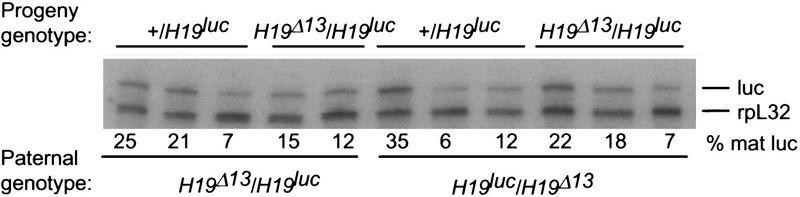

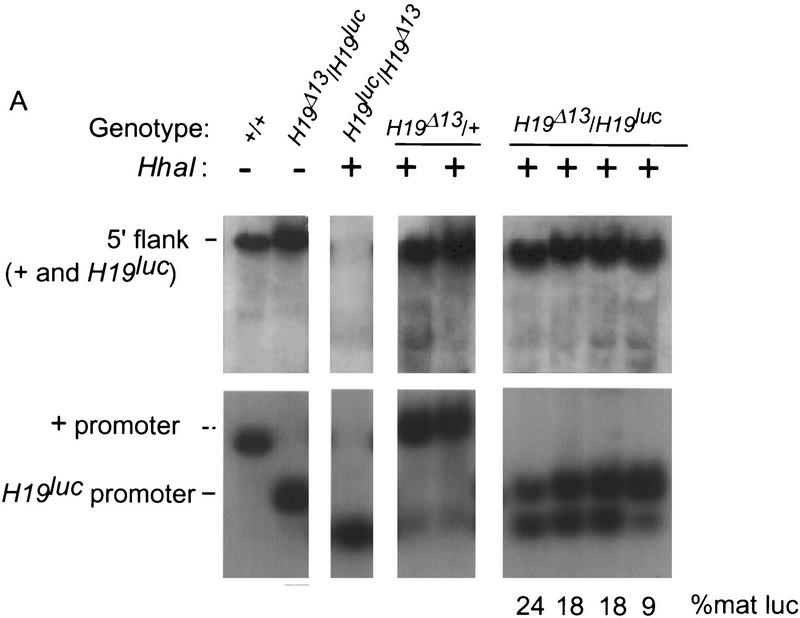

To examine the basis for the variability, the levels of luc methylation in progeny showing relaxation of the imprint after paternal inheritance were examined. To simplify the analysis, we used tissues from H19Δ13/H19luc animals in which the H19 gene and its 5′ flank were deleted on the maternal chromosome. In progeny exhibiting the lowest levels of luc expression, the methylation pattern was indistinguishable from that observed on a wild-type paternal H19 gene throughout the 5′ flank; that is, both the 4-kb SacI fragment encompassing the gametic imprint as well as the smaller promoter fragment resisted digestion with HhaI. Moreover, this methylation extended into the luc gene itself, reminiscent of the methylation of the H19 structural gene (data not shown). In contrast, in animals in which the expression of luc was detected, there was an inverse correlation between the expression level and the degree of methylation of the promoter, but not the 5′ gametic imprint region, which remained fully methylated (Fig. 5). Thus, the replacement of the H19 structural gene with the luc gene results in some degree of undermethylation of the promoter and sporadic expression of luc. This result suggests that sequences within the H19 structural gene contribute to the maintenance of its silent state on the paternal chromosome. CpG density alone, however, cannot account for this, as the luc gene, which is almost identical in length to H19, has almost twice the number of CpG dinucleotides. On the other hand, the luc gene’s overall G+C content is 43%, which is closer to the genome average than H19, which is 56%.

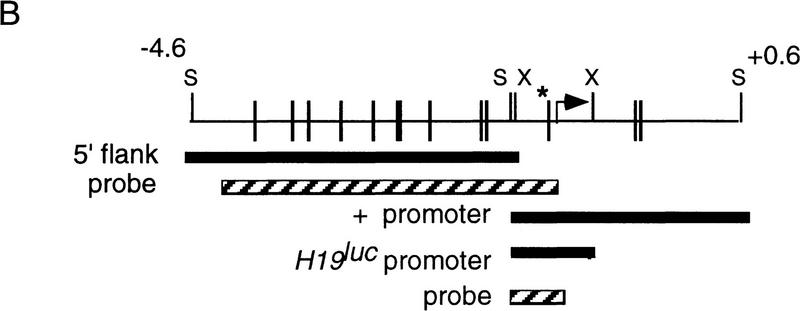

Figure 5.

Effect of paternal H19luc inheritance on DNA methylation. (A) Genomic DNA from livers of wild-type (+/+), +/H19luc heterozygotes, and H19Δ13/H19luc homozygotes were digested with SacI and XbaI alone (−, first two lanes) or SacI, XbaI, and HhaI (+), separated on 1% agarose gels, and hybridized to a 4-kb EcoRI fragment that detects the 3.8-kb SacI fragment in the 5′ flank of the + and H19luc alleles (top) or a 600-bp XbaI–EcoRI fragment from the 5′ end of the H19 gene that detects a 1.2-kb SacI fragment encompassing the + promoter and a 0.7-kb XbaI fragment encompassing the H19luc promoter (bottom). The level of expression of paternal luc RNA in the four compound heterozygotes is indicated as a percent of maternal luc RNA expression. (B) A map of the H19 5′ region, with the start of transcription indicated by the arrow, is drawn below, along with the positions of the SacI and XbaI fragments assayed (solid rectangles). (S) SacI; (X) XbaI. (|) HhaI; (*) HhaI site assayed in the bottom of A. The probes used in A are indicated by hatched boxes.

The sporadic expression of luc on the paternal chromosome provides an explanation for the failure of H19–luc fusion transgenes to be imprinted (Pfeifer et al. 1996). One difference between the luc transgene and the germ-line replacement is the maintenance of DNA methylation in the 5′ flank in the latter. It may be that the 14-kb transgenes contained only a subset of the epigenetic information required for maintenance of DNA methylation, a conclusion that is consistent with the recent observation that single copy 130-kb YAC transgenes of the locus are correctly imprinted (Ainscough et al. 1997).

H19luc expression has no effect on Igf2 expression

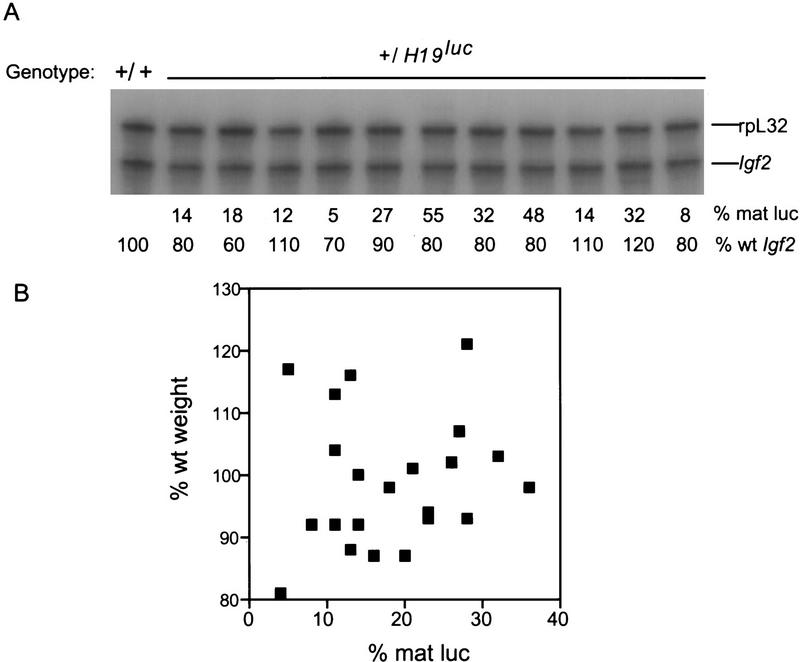

It was of considerable interest to ask whether transcription of luc on the paternal chromosome affected Igf2 expression. If a strict competition for transcription governs its expression, we would anticipate a decrease, analogous to the effect of mutations in the β-globin gene promoter on γ-globin gene expression in chickens, in which promoter competition has been clearly demonstrated (Choi and Engel 1988; Foley and Engel 1992). However, there was no correlation between the levels of Igf2 RNA (normalized to rpL32 RNA levels) and the expression of paternal luc RNA (Fig. 6A). Moreover, the birth weights of the animals were unaffected by paternal luc expression (Fig. 6B). These data argue against a strict competition between the H19 and Igf2 promoters in maintaining imprinted Igf2 expression.

Figure 6.

Effect of paternal luc expression on Igf2 expression. (A) Expression of Igf2 and rpL32 RNAs in paternal H19luc heterozygotes was determined by an RNase protection assay (Webber et al. 1998). The level of luc RNA in each animal is indicated as a percent of maternal luc RNA, and the level of Igf2 RNA is expressed as a percent of that in wild-type embryos after normalization to rpL32 RNA by PhosphorImager densitometry. (B) The weights of +/H19luc neonatal offspring (expressed as percent of mean +/+ littermate weight) were plotted against paternal luc RNA expression (expressed as percent of maternal luc RNA levels).

Discussion

The maintenance of Igf2 imprinting in mice that have substituted luc for the H19 coding region rules out a role for H19 RNA itself in imprinting. Two previous mutations at the locus, both of which removed both the H19 gene and its promoter, had resulted in the inappropriate expression of the maternal Igf2 gene (Leighton et al. 1995a; Ripoche et al. 1997). These findings, coupled with the demonstration by Marahrens et al (1997), that the Xist gene itself is required for X chromosome inactivation, made the H19 RNA an attractive candidate for playing a role in imprinting. However, this is clearly not the case. Instead, the important epigenetic mark for Igf2 imprinting must lie in the vicinity of the promoter and the 5′ flank of the H19 gene.

The fact that the H19luc mice display no phenotype whatsoever leaves unexplained the evolutionarily conserved primary sequence and secondary structure of the RNA (Brannan et al. 1990; Pfeifer and Tilghman 1994). It could be that the RNA has a function unrelated to imprinting that is either nonessential or redundant. Alternatively, it could be that the sole function of the gene is to be transcribed at high rates to imprint Igf2 and that the conservation of its product reflects the necessity of packaging and sequestering a very abundant RNA. If so, this would be an entirely novel function for a gene.

From the outset, the epigenetic configuration of the Igf2 and H19 genes suggested that the genes were not being regulated identically. The finding of extensive methylation of the paternally inherited H19 gene suggested a straightforward explanation for its silence, given the long-standing correlation between gene silencing and DNA methylation. Furthermore, the differential hypersensitivity of the maternal and paternal H19 promoters to nuclease digestion reinforced the idea that the two alleles were in different chromatin conformations (Bartolomei et al. 1993; Brandeis et al. 1993; Ferguson-Smith et al. 1993). In contrast, Igf2 is methylated exclusively on the expressed paternal chromosome, and the two parental promoters are in equally hypersensitive states (Sasaki et al. 1992). Despite the correlation between Igf2 methylation and expression observed in vivo, our findings demonstrate that this methylation is not required for Igf2 expression, but is likely the consequence of its expression.

The initial model proposed by Bartolomei and Tilghman (1992) suggested that the transcriptional status of H19 was mediating the imprinting of Igf2. The possibility of pairing a transcription unit that is the target of epigenetic information (i.e., H19) with an oppositely imprinted response gene (Igf2) has now been raised for another imprinted gene, Igf2r. Like Igf2, its methylated epigenetic mark occurs on the expressed maternal chromosome, within a large intron of the gene (Stoger et al. 1993). Wutz et al (1997) have now shown that this CpG island is the promoter for a paternally expressed antisense transcript that is required for Igf2r imprinting. Barlow (1997) has suggested that the mechanism underlying Igf2r imprinting is promoter competition with the antisense RNA coding gene, like the one we have described at Igf2 and H19.

More recent observations suggest that imprinting control may be more complex than strict promoter competition. First, in an effort to understand the basis for the competition between Igf2 and H19, we transposed the 3′ H19 enhancers to a position midway between the genes (Webber et al. 1998). To our surprise, the Igf2 gene was expressed to the exclusion of H19, essentially reversing the direction of the imprint on the maternal chromosome. This argues that the position of a gene and its enhancers relative to the epigenetic mark may play a crucial role in the nature and direction of the imprint.

Second, in this report we observed significant levels of expression of the paternal luc gene without a concomitant change in the expression of Igf2, a finding that directly contradicts strict promoter competition. It is possible that the substitution of the luc gene for H19 reduced the transcription rate from the H19 promoter, and thus, it is a poor competitor for transcription with Igf2. However, if this were the case, according to strict promoter competition, one might have expected an increase in maternal Igf2 expression. Rather, it appears that the reciprocal expression of H19 and Igf2 is unlike that between the adult and embryonic chicken β-globin genes, in which an increase in expression of one gene is always accompanied by a decrease in the other (Foley and Engel 1992). Our data show that the H19 promoter can be active on the paternal chromosome without decreasing Igf2 expression. On the basis of both of these studies, we propose that it is the methylation of the epigenetic mark upstream of H19 that is essential for Igf2 expression, and would further suggest that the function of methylating this mark may be to inactivate a chromatin boundary that isolates Igf2 from the downstream enhancers. On the maternal chromosome, where the epigenetic boundary is unmethylated, and therefore active, Igf2 is insulated from its transcriptional regulatory elements.

Material and methods

Mutant genotyping

Dmnt genotyping was accomplished by a PCR reaction that detected both the wild-type locus with forward Dmnt 1114 primer (5′-CCTTCAGTGTGTACTGCAGTCG-3′) and reverse Dmnt 1169 primer (5′-AATGAGACCGGTGTCGACAG-3′) and the targeted locus with forward Dmnt 1114 primer and reverse Pgk3 primer (5′-CTTGTTGTAGCGCCAAGTGC-3′). Genomic DNA (100 ng) was amplified for 35 cycles at 90°C for 30 sec, 53°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec in 20 μl.

H19Δ13 is a replacement from an EcoRI site at −10 kb to a SalI site at +3 kb at the H19 locus with the Pgkneo cassette (Leighton et al. 1995a). Genotyping was performed by use of the forward primer in the region 5′ of the H19Δ13 deletion (5′-CAGTGTGGGAAACAGCCT-3′) and Pgk3 for the reverse primer. luc genotyping by PCR utilized the forward primer LH195′ (5′-GCCATGTACTGATTGGTTGA-3′) and the reverse primer Luc3′ (5′-TTGCTCTCCAGCGGTTCCAT-3′). Conditions for amplificaton were identical to those used for Dmnt genotyping.

RNA analysis

RNAs were prepared from pools of from four to five embryos in the Dnmt;H19Δ13 crosses with the RNaqueous kit from Ambion. Ten micrograms of each RNA were hybridized to radiolabeled RNA antisense probes specific for rpL32 (Webber et al. 1998), Igf2 (Leighton et al. 1995a), and H19 (Brunkow and Tilghman 1991) by use of the Ambion RPAII kit. Protected fragments were resolved by electrophoresis on 7.5% denaturing acrylamide gels run in 1× TBE.

The luc riboprobe was generated by ligating a 540-bp XbaI–EcoRI fragment from pGL2 into BS KSII−, linearizing with BsrFI and transcribing with T3 polymerase. Ten micrograms of total neonatal liver RNA was used in each assay.

Generation of H19luc mutant mice

H19 genomic clones were isolated from a 129Sv/J bacteriophage genomic library (Stratagene). A BglII–DraIII fragment of the H19 5′ flank from −1.8 kb to +3 bp and a SalI–BglII 6.5-kb fragment of H19 3′-flanking sequence were cloned into Bluescript KSII−. The luc was isolated from the pGL2 vector (Promega) as a HindIII–SalI fragment and ligated to the 5′ arm. The diptheria toxin A-chain cassette was ligated downstream of the 3′ homologous sequence. neo/tk (Wu et al. 1994) was ligated between two tandem loxP sites and inserted immediately 3′ of luc in the final targeting vector. E14.1 ES cells (Kuhn et al. 1991) were transfected as described (Webber et al. 1998) and selected for 6–7 days with 200 μg/ml G418 (active) before picking neoR clones. Cre excision and derivation of chimeric mice and germ-line offspring were performed as described (Webber et al. 1998).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rudolph Jaenisch for providing the Dnmt mutant mice, and members of the laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. B.K.J. is supported by a National Research Service Award from the National Institutes of Health and S.M.T. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL stilghman@molbio.princeton.edu; FAX (609) 258-3345.

References

- Ainscough JF-X, Koide T, Tada M, Barton S, Surani A. Imprinting of Igf2 and H19 from a 130 kb YAC transgene. Development. 1997;124:3621–3632. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DP. Gametic imprinting in mammals. Science. 1995;270:1610–1613. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5242.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Competition—A common motif for the imprinting mechanism? EMBO J. 1997;16:6899–6905. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei MS, Tilghman SM. Parental imprinting of mouse chromosome 7. Semin Dev Biol. 1992;3:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- ————— Genomic imprinting in mammals. Annu Rev Genet. 1997;31:493–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei MS, Zemel S, Tilghman SM. Parental imprinting of the mouse H19 gene. Nature. 1991;351:153–155. doi: 10.1038/351153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei MS, Webber AL, Brunkow ME, Tilghman SM. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying the imprinting of the mouse H19 gene. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:1663–1673. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.9.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandeis M, Kafri T, Ariel M, Chaillet JR, McCarrey J, Razin A, Cedar H. The ontogeny of allele-specific methylation associated with imprinted genes in the mouse. EMBO J. 1993;12:3669–3677. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan CI, Dees EC, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM. The product of the H19 gene may function as an RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:28–36. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkow ME, Tilghman SM. Ectopic expression of the H19 gene in mice causes prenatal lethality. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:1092–1101. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary T, Cleary MA, Baker CC, Guan X-J, Tilghman SM. Multiple mechanisms regulate imprinting of the distal chromosome 7 gene cluster. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3466–3474. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi O-RB, Engel JD. Developmental regulation of β-globin switching. Cell. 1988;55:17–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChiara TM, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Parental imprinting of the mouse insulin-like growth factor II gene. Cell. 1991;64:849–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90513-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil R, Walter J, Allen ND, Reik W. Developmental control of allelic methylation in the imprinted mouse Igf2 and H19 genes. Development. 1994;120:2933–2943. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson-Smith AC, Sasaki H, Cattanach BM, Surani MA. Parental-origin-specific epigenetic modifications of the mouse H19 gene. Nature. 1993;362:751–755. doi: 10.1038/362751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley KP, Engel JD. Individual stage selector element mutations lead to reciprocal changes in β- vs. ε-globin gene transcription: Genetic confirmation of promoter competition during globin gene switching. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:730–744. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forne T, Oswald J, Dean W, Saam JR, Bailleul B, Dandolo L, Tilghman SM, Walter J, Reik W. Loss of maternal H19 gene induces changes in Igf2 methylation in both cis and trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:10243–10248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay GF, Penny GD, Patel D, Ashworth A, Brockdorff N, Rastan S. Expression of Xist during mouse development suggests a role in the initiation of X chromosome inactivation. Cell. 1993;72:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90658-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science. 1991;254:707–713. doi: 10.1126/science.1948049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton PA, Ingram RS, Eggenschwiler J, Efstratiadis A, Tilghman SM. Disruption of imprinting caused by deletion of the H19 gene region in mice. Nature. 1995a;375:34–39. doi: 10.1038/375034a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton PA, Saam JR, Ingram RS, Stewart CL, Tilghman SM. An enhancer deletion affects both H19 and Igf2 expression. Genes & Dev. 1995b;9:2079–2089. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992;69:915–926. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, Beard C, Jaenisch R. The role of DNA methylation in genomic imprinting. Nature. 1993;366:362–365. doi: 10.1038/366362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marahrens Y, Panning B, Dausman J, Strauss W, Jaenisch R. Xist-deficient mice are defective in dosage compensation but not spermatogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:156–166. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarrick III JW, Parnes JR, Seong RH, Solter D, Knowles BB. Positive-negative selection gene targeting with the diphtheria toxin A-chain gene in mouse embryonic stem cells. Transgenic Res. 1993;2:183–190. doi: 10.1007/BF01977348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutirangura A, Jayakumar A, Sutcliffe JS, Nakao M, McKinney MJ, Buiting K, Horsthemke B, Beaudet AL, Chinault AC, Ledbetter DH. A complete YAC contig of the Prader-Willi/Angelman chromosome region (15q11-q13) and refined localization of the SNRPN gene. Genomics. 1993;18:546–552. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(11)80011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny GD, Kay GF, Sheardown SA, Rastan S, Brockdroff N. Requirement for Xist in X chromosome inactivation. Nature. 1996;379:131–137. doi: 10.1038/379131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer K, Tilghman SM. Allele-specific gene expression in mammals: The curious case of the imprinted RNAs. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:1867–1874. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer K, Leighton PA, Tilghman SM. The structural H19 gene is required for its own imprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:13876–13883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripoche M-A, Kress C, Poirier F, Dandolo L. Deletion of the H19 transcription unit reveals the existence of a putative imprinting control element. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:1596–1604. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.12.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougeulle C, Glatt H, Lalande M. The Angelman syndrome candidate gene, UBE3A-AP, is imprinted in brain. Nature Genet. 1997;17:14–15. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Jones PA, Chaillet JR, Ferguson-Smith AC, Barton S, Reik W, Surani MA. Parental imprinting: Potentially active chromatin of the repressed maternal allele of the mouse insulin-like growth factor (Igf2) gene. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:1843–1856. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer B, Henderson N. Cre-stimulated recombination at loxP-containing DNA sequences placed into the mammalian genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:147–161. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoger R, Kubicka P, Liu C-G, Kafri T, Razin A, Cedar H, Barlow DP. Maternal-specific methylation of the imprinted mouse Igf2r locus identifies the expressed locus as carrying the imprinting signal. Cell. 1993;73:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90160-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson K, Walsh C, Fundele R, Ohlsson R. H19 is imprinted in the choroid plexus and leptomeninges of the mouse foetus. Mech Dev. 1995;51:31–37. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)00345-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo PE, Mann JR. Biallelic expression of imprinted genes in the mouse germ line: Implications for erasure, establishment, and mechanisms of genomic imprinting. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1857–1868. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay KD, Saam JR, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM, Bartolomei MS. A paternal-specific methylation imprint marks the alleles of the mouse H19 gene. Nature Genet. 1995;9:407–413. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay KD, Duran KL, Bartolomei MS. A 5′ two kilobase pair region of the imprinted mouse H19 gene exhibits exclusive paternal methylation throughout development. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4322–4329. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker KL, Beard C, Dausman J, Jackson-Grusby L, Laird PW, Lei H, Li E, Jaenisch R. Germ-line passage is required for establishment of methylation and expression patterns of imprinted but not of nonimprinted genes. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1008–1020. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu TH, Hoffmann AR. Imprinting of Angelman syndrome gene, UBE3A, is restricted to brain. Nature Genet. 1997;17:12–13. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter J, Allen N, Kruger T, Engemann S, Kelsey G, Feil R, Forne T, Reik W. Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. Genomic imprinting and modifier genes in the mouse; pp. 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Webber A, Ingram RI, Levorse J, Tilghman SM. Location of enhancers is essential for imprinting of H19 and Igf2. Nature. 1998;391:711–715. doi: 10.1038/35655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wevrick R, Kerns JA, Francke U. Identification of a novel paternally expressed gene in the Prader-Willi syndrome region. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1877–1882. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.10.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Liu X, Jaenisch R. Double replacement: Strategy for efficient introduction of subtle mutations into the murine Colla-1 gene by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:2819–2823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wutz A, Smrzka OW, Schweifer N, Schellander K, Wagner EF, Barlow DP. Imprinted expression of the Igf2r gene depends on an intronic CpG island. Nature. 1997;389:745–749. doi: 10.1038/39631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemel S, Bartolomei MS, Tilghman SM. Physical linkage of two mammalian imprinted genes. Nature Genet. 1992;2:61–65. doi: 10.1038/ng0992-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]