Abstract

Purpose: The Shared Hospital Electronic Library of Southern Indiana (SHELSI) research project was designed to determine whether access to a virtual health sciences library and training in its use would support medical decision making in rural southern Indiana and achieve the same level of impact seen by targeted information services provided by health sciences librarians in urban hospitals.

Methods: Based on the results of a needs assessment, a virtual medical library was created; various levels of training were provided. Virtual library users were asked to complete a Likert-type survey, which included questions on intent of use and impact of use. At the conclusion of the project period, structured interviews were conducted.

Results: Impact of the virtual health sciences library showed a strong correlation with the impact of information provided by health sciences librarians. Both interventions resulted in avoidance of adverse health events. Data collected from the structured interviews confirmed the perceived value of the virtual library.

Conclusion: While librarians continue to hold a strong position in supporting information access for health care providers, their roles in the information age must begin to move away from providing information toward selecting and organizing knowledge resources and instruction in their use.

BACKGROUND

The rapidly changing fields of health care, telecommunications, and computer technology converge at the virtual medical library. The virtual medical library has no specific physical location but is ubiquitous through the Internet with the text, graphics, and hypertext capabilities of the Web. It provides knowledge-based information from the traditional print formats of text and reference books, journal articles, and indexes to journal articles and less traditional formats such as practice guidelines, drug information, and patient-education databases. The potential for audio, streaming video, and interactive data collection forms exists. The virtual library is mobile, requires only a conveniently located computer, and is available on demand. To the untrained novice, navigating the virtual library is intimidating and frequently unproductive—similar to the inexperienced library user in a traditional medical library.

In 1999, a National Library of Medicine (NLM) Information Access Grant (1-G07-LM06611–01A1) provided a virtual medical library for eighteen health care institutions and unaffiliated health professionals in southwestern Indiana. The project, called Shared Hospital Electronic Library of Southern Indiana (SHELSI), had a Web home site that linked to purchased electronic resources as well as free materials on the Web. Training sessions were offered to health professionals. As part of the evaluation process, a form for SHELSI users to submit data on the use of the SHELSI resources was linked from the home page. Structured interviews with a sample of primary care providers that used the resources were conducted, and the perceptions of the value of the SHELSI resources were documented.

The geographic region for the project extends southward from central Indiana to the Ohio River and west from Bloomington in the center of the state to the Illinois state line. It covers 7,750 square miles with a population of approximately 900,000. The region is mostly rural with sparsely populated areas that are medically underserved. The urban areas on the perimeter of the region have hospital libraries. Indiana has no Area Health Education Center (AHEC), and previous arrangements for supplying information service to the small rural hospitals in the northern part of the region have collapsed. Many of the hospitals have no arrangements for information service.

Four hospital librarians participated in the project by serving on the SHELSI Advisory Board and encouraging health professionals to participate in the training. None of the hospitals in the region used DOCLINE at the beginning of the project. One hospital had 200 current subscriptions, and the remainder had fewer than seventy subscriptions. The total of hospital library journal subscriptions was less than 700. The supply and currency of text and reference books was also an issue in most of the institutions. An outreach project introducing health professionals in this region to Internet Grateful Med, PubMed, and other Internet resources was conducted in 1998. The southwestern section of the state comprised the target area for Phase 1 of the planned two-phase project for all of southern Indiana.

Marshall's Rochester study [1] and the Klein article [2] documented the value of hospital library services. However, these services are nonexistent in many rural areas, and other options for information service have been explored through outreach projects in other parts of the country. Burnham [3] questioned why the outreach projects introducing MEDLINE and Loansome Doc to rural health professionals have not worked. Dorsch [4, 5] defined some of the barriers for information service to rural health professionals and actions to resolve the barriers. The Dee article [6] emphasized the fact that MEDLINE and the journal literature alone were not enough to serve the information needs of rural health professionals. The need according to Dee was for “immediate access to high-quality, synthesized answers to specific patient care questions at the time of patient contact” [7]. These findings implied that the efficacy of any plan for serving the information needs of rural primary care providers depended upon immediate and appropriate access to current electronic textbooks and journals as well as indexes to the journal literature.

THE PROJECT

The SHELSI project originated in December of 1996, when representatives from health care institutions in southern Indiana attended a meeting to discuss the SHELSI vision. Thirty institutions indicated an interest in participating and an Information Access Grant proposal for SHELSI was submitted to the National Library of Medicine in June of 1997. The review of that proposal suggested dividing the project into smaller geographic areas. The SHELSI Phase 1 project proposal was submitted in March of 1998, and the project began in March of 1999. The southwestern section was selected for the first phase because of the comparative strength of support from hospital libraries. The southeastern portion had only one trained hospital librarian, and the need in this area was more profound than in the southwestern section. The success of Phase 1 would be a determinant in funding the proposal for Phase 2. Each participating institution signed a memorandum of agreement specifying certain conditions of participation that included continued support of the project after the grant expired.

Prior to the submission of the first proposal in 1997, a needs assessment was done to determine the extent of use of medical information, barriers to use, and use of computers and electronic information by health professionals in southern Indiana. The survey instrument was a Likert-type questionnaire, eliciting opinions from the health care users with the choices of “never,” “seldom,” “some,” “usually,” and “always.” The surveys were distributed by participating hospital representatives. Nearly 600 of the surveys were returned, and a number of broad conclusions were drawn from the results of this survey. Of the returned surveys, 507 were considered usable. This sample was composed of 170 physicians, 224 nurses, and 113 in the “other” category, including such allied health professions as physicians' assistants, physical therapists, and optometrists.

Most of the respondents, regardless of profession or specialization, felt that they encountered questions in their practice that could be answered by ready access to medical literature; if they did encounter such questions, they indicated that they frequently used books or journal articles to find the answers. They also felt that practice guidelines had relevance to their practice. When looking at obstacles, the majority of the respondents identified lack of both time and ready access to resources as primary problems. Potential costs associated with timely access to needed information was more significant to non-doctors.

Responses to questions about the use of computers indicated that most respondents would use a computer to access electronic resources if such access were available. However, the professions diverged in terms of perceptions of availability of hardware. Physicians felt that they already had convenient access to computers, while nurses and other health care providers did not. Only nurses felt that their lack of computer training would present a barrier to information retrieval.

The more traditional forms of information access, the use of MEDLINE and the acquisition of needed articles, were not routinely used by the respondents. To attempt to obtain a granular response, the issue of MEDLINE access was queried in two questions—one attempting to ascertain whether respondents used the database themselves and the second asking if they used a librarian or another individual to perform searches. The answer to both queries was negative.

In looking at the use of the Internet, most of the respondents did not use email, did not use a browser to search the Web, and had never found useful, patient-related information on the Web. Concomitantly, the majority indicated that their patients never or seldom researched their own diagnoses. The findings from the Internet questions on the 1997 survey would probably differ today with the growing access to Internet technology in this area.

In December of 1996, all twenty-three hospitals in the eighteen-county, southwestern Indiana region were invited to participate in the project. Fourteen of these hospitals agreed. Each institution was asked to sign a memorandum of agreement to (1) commit a hospital representative to serve as liaison for the training, (2) provide an unspecified amount of funding for succeeding years if the project were deemed successful, (3) participate in DOCLINE if the hospital had a sufficient collection of information resources, and (4) locate the project computer where it could accessed by an optimum number of health professionals. Lack of interest by the hospital administration or concern for ongoing financial commitment were the main reasons that nine of the hospitals did not participate. Three rural health clinics and a mental health clinic were among the original participating institutions. By the time the project was funded, two of the rural health clinics had received a telemedicine grant that included funding for electronic library resources and were no longer interested in participating in SHELSI. Invitations to join SHELSI were sent to the nonparticipating hospitals in the eighteen-county region. Two more hospitals joined the project, so that there were sixteen hospitals, a mental health clinic, and a rural health clinic as Phase 1 SHELSI participants.

When implemented, the SHELSI project provided a computer for each institution that agreed to participate. Other elements for the project included creating a SHELSI Website, training hospital liaisons to use the virtual library resources, providing hands-on training to health professionals in the region that were registered with the Indiana Bureau of Health Professionals, and collecting data that documented how the resources were used. A SHELSI Advisory Board was created. A physician, a nurse, a hospital administrator, a person providing library service in one of the smaller hospitals, and the four hospital librarians comprised the board. The board was actively involved in the selection of resources, other administrative details, and plans for continuing the consortium.

The SHELSI Website is hosted by InCOLSA, the state's library service agency. The virtual library collection consists of the resources on MD Consult (thirty-five medical textbooks, an index to the journal literature, the full content of forty-eight journals, a patient-education database, a drug information database, and a collection of practice guidelines); NLM's PubMed, Loansome Doc, and MEDLINEplus; article access to the Special Collection of Northern Light for nursing full-text materials; The Guidelines Clearinghouse; and the EBSCOhost databases in Indiana's Inspire collection. Links to free materials on the Web are selected by a hospital librarian and collected under buttons designated for physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and so on.

Training sessions of differing formats, locations, and times of day were developed for health professionals. Three-and-one-half-hour hands-on training sessions were offered in computer classrooms at higher education institutions distributed throughout the eighteen-county area. Publicity brochures listing all the scheduled sessions were created and distributed using mailing labels created by the Indiana Bureau of Health Professionals from its database of registered health professionals. The use of these labels ensured that health professionals throughout the region were invited to participate without regard to hospital affiliation. A total of 15,000 training-session announcements were distributed by U.S. Mail. Approximately 10% of these mailed items were returned due to insufficient addresses.

Registration with a small fee for these sessions was required, and continuing-education credit was arranged for physicians and nurses. Demonstration sessions were given at most of the participating hospitals. Abbreviated hands-on sessions were given at the urban hospitals with small computer-training rooms. Participants in the training were strongly encouraged to submit data about the use of the SHELSI resources.

Both to evaluate the project and to provide feedback in preparation for the Phase 2 submission, a two-part research protocol was designed. The first part was a forms-based questionnaire to be used with the participants' initial and subsequent accesses to the electronic information. The second part involved structured interviews designed to ascertain whether or not the information access had an impact on improved health care outcomes.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A database of all the individuals who had a formal introduction to SHELSI was created. Lack of formal instruction did not preclude use of resources for eligible health care providers but did exclude them from the initial research phase. Individuals in the database comprised the population for the survey. Health professionals at two institutions were trained by project liaisons and were not included in the database. The total number in the database slightly exceeded 400 and included physicians, nurses, social workers, speech pathologists, physical and occupational therapists, hospital liaisons, and a small number of others. Of the more than four hundred health providers in the database, sixty-one were physicians, and 130 were nurses. Nursing faculty at the host training sites accounted for approximately one-fourth of the nurses. More than one-third of the names were not affiliated with the hospitals participating in the project. A shareware counter was put on the SHELSI Website, and the number of hits averaged 2,000 per month during the training months. The average number of SHELSI accesses in the maintenance period has stabilized at about 800 per month.

A data collection form was designed to determine which SHELSI resources were used, the extent of use of these resources, the locations where the virtual library was accessed, the intended use of the information, the impact of the information on decision making, and the perceived influence of the information on health care outcomes. Sections of the survey were modeled on the instrument used in the Rochester study [8]. A pilot test of the instrument was conducted at a nonparticipating hospital a month before the training sessions began. Paper copies of the survey instrument were distributed in the early training sessions; later a Web version of the instrument was added to the SHELSI Website. Participants were encouraged to complete and return the forms, because data was needed for the evaluation component of the grant-funded project, and project continuation depended upon a demonstration of use and usefulness. Participants were instructed to submit data on single uses of SHELSI resources.

A structured interview form was developed for the interviews to be conducted at the end of the project. The interview was designed to determine the perceived value and impact of SHELSI on primary care providers in the region. Statements were formulated with responses for varying degrees of agreement. For the first interviews, physicians were selected from those who had submitted data indicating use of the system. A physician's assistant and nurse practitioner were subsequently added to the sample. MD Consult provided data that indicated recent use of the service; potential candidates for the interviews were selected from both early users of the system and those that had used MD Consult within one month of the scheduled interview. One interview participant had been trained by the local hospital liaison and was not in the database.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

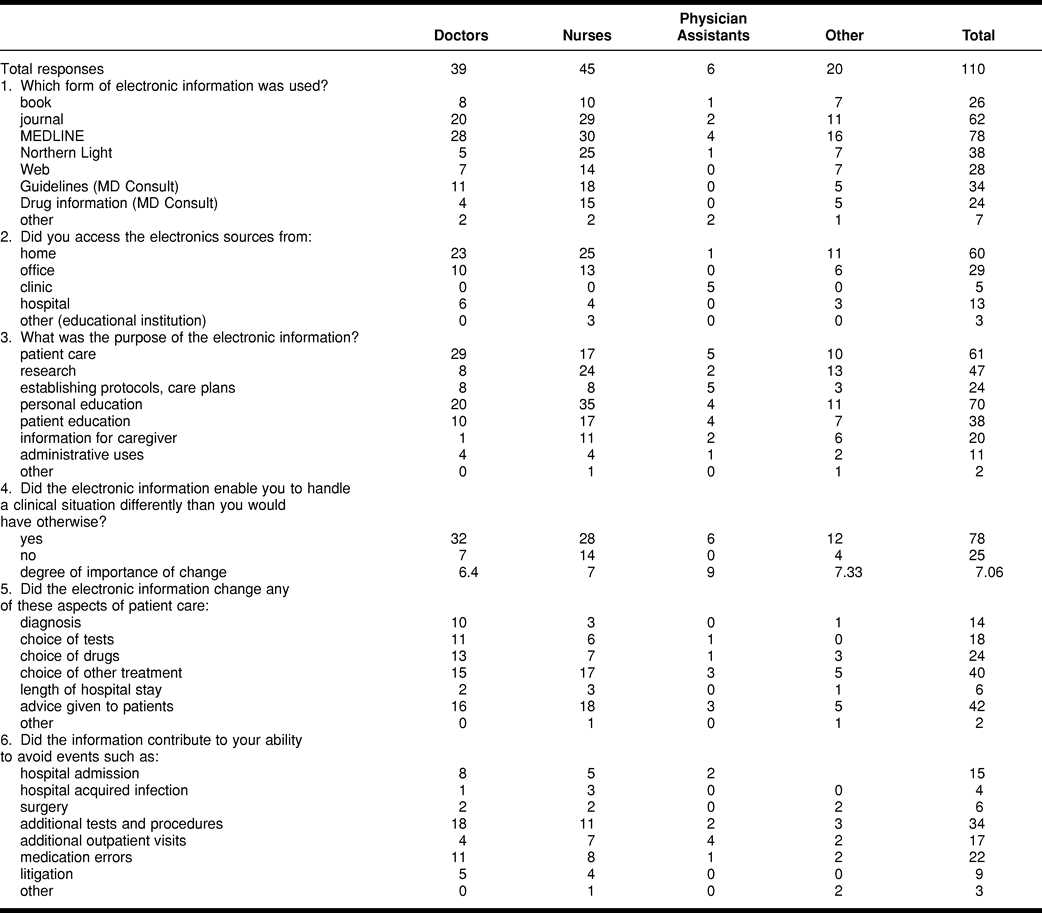

More than 200 data-collection forms were completed. Those forms from educators, hospital liaisons, and other nonclinicians as well as those from health professionals who did not participate in training were not used in the results. One hundred and ten responses (39 from physicians, 45 from nurses, 6 from physicians assistants, and 20 from the “other” category) were used in the analysis. The questions and the results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Use of SHELSI resources

The first question addressed preferred resources. Multiple responses were accepted. MEDLINE and the full-text journals were the most heavily used. The drug information, textbooks, and guidelines on MD Consult were also accessed. The average number of sources used by all respondents to answer information questions was 2.7. Physicians and physicians' assistants tended to use fewer sources, while nurses frequently used three or more sources. Because of the relatively small numbers in the stratification of the sample, there was no attempt to correlate the number of resources used with the type of information query.

While the intent of the virtual library project was to provide information at the point of clinical decision making, the majority of survey respondents indicated that they used the system from home. Based on the question of computer access in the needs assessment, this preference for use of the virtual library resources at home might relate to the perception that there was little or no computer access in the workplace.

In seeking data about the reasons for accessing information resources, personal education was the most common reason cited, followed closely by need for information to support patient care. Research and patient education were also significant determinants for use. In looking at the stratification of the professions, physicians primarily used the virtual library for patient care, while nurses and physicians' assistants used the information more for continuing education and patient education. Multiple reasons could be indicated in response to the question, and the information tended to meet 2.5 disparate needs among the user population.

Questions 4 through 6 asked for perceptions from the health professional about the perceived impact of the information access on their clinical decision making and health care outcomes. Question 4 asked if the electronic information enabled the respondents to handle a clinical situation differently than they would have otherwise. Seventy-five percent responded “yes,” and the degree of importance of change averaged 7 on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 having the highest impact. More than 80% of the physicians in the sample responded in the affirmative, although their perceived level of impact was less, at 6.4.

When queried about which aspects of patient care were influenced by the obtained information, advice given to patients and choice of treatment were the most frequent responses, with choice of drugs and choice of tests also having significant scores. Individual physician access to information resources tended to impact two aspects of health care delivery, while other health care providers indicated that such access resulted in a single change. A possible reason for this difference might lie with the ability of physicians to affect more aspects of health care delivery.

One of the greatest problems facing health care today involves adverse events that occur in health settings. These commonly include nosocomial infections, medication errors, additional visits to the health care provider, and length of stay in a health care facility. In asking the users of the virtual library to identify possible adverse events that were avoided by information access, the primary positive perceived impact was in a reduced need for additional tests and procedures. Other areas in which information access made a significant impact were in reduced medication errors, reduced need for additional outpatient visits, and reduced need for hospital admissions.

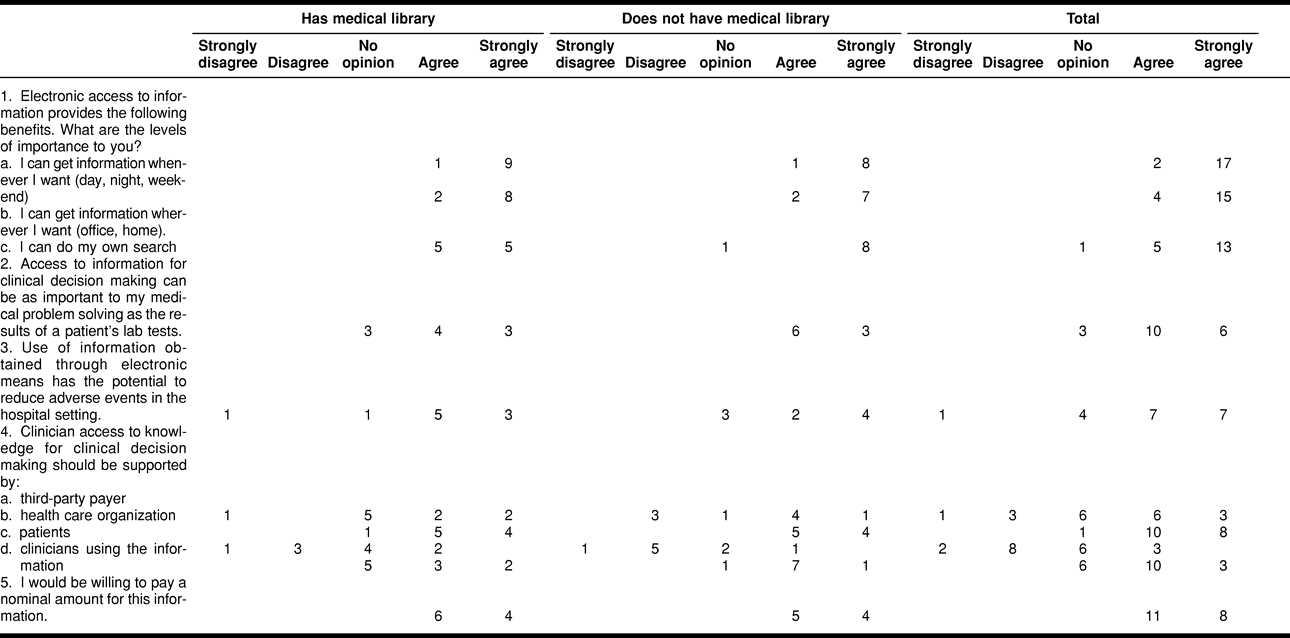

The structured interviews were conducted three months following the full implementation of the project. Nineteen interviews were completed with seventeen physicians, a physician's assistant providing primary care, and a nurse practitioner. The responses were broken down into two categories: those with access to a traditional medical library and those without. Ten had access to a medical library, and nine did not. One of the respondents indicated that she had access to a medical library, although there was no formal library service available through her respective health care facility. Based on the provider response, data from this interview were included in the “with library” group. The numerical results of the structured interviews are found in Table 2.

Table 2 Interview results

Question 1 of the interview focused on which elements of the virtual library project were of value. The respondents overwhelmingly agreed that accessing information when and where they chose was important. While those who did not have ready access to a medical library felt that the ability to perform their own searches was of high importance, half of those who had library access felt that the ability to do their own searches was only of moderate importance.

Question 2 attempted to determine the relative value of the information access when compared to information gleaned from the patient. Six of the nineteen responses strongly agreed that convenient information was as important as patient lab results, while ten agreed, and three offered no opinion. In the area of whether the respondents felt that knowledge-based information had the potential to positively impact adverse events in hospitals (Question 3), the majority felt that it did. However, one respondent strongly disagreed with this hypothesis, and four had no opinion, differing with the suggested findings of the impact survey.

Questions 4 and 5 looked at the costs of information access. There was fairly uniform consensus that patients should not pay for information access for their health care providers. Similarly, most of the respondents felt that the health care organizations should underwrite the service. There was also sentiment for support from third-party payers and clinicians using the information. To test the “real” value, the final question asked if the respondents themselves would be willing to pay, and all answered in the affirmative.

The questions of the structured interview were deliberately brief to give respondents an opportunity to respond to a more open-ended query about how access to the information has affected practice. Many of the responses dealt with the ability to quickly obtain information about obscure diagnoses or treatment of medical conditions not commonly seen. The ability to keep current was of significant importance. Several of the less common responses included a statement about the increased use of patient-education materials because of their immediate accessibility through the system, a statement about how information access contributed to more expedient and cost-effective delivery of health care, and a statement by the untrained health care provider about how valuable a training session would have been to enable efficient access to the information resources.

The results of both the survey and the structured interviews indicated that health care providers in a rural area of Indiana received significant benefits from access to a rural virtual medical library designed to provide information resources targeted to specific health care information needs. The initial feedback about the value of the training sessions led to the hypothesis that education in the use of the resources was a critical component to both the efficiency and effectiveness of the information access. Research in Phase 2 of SHELSI will be designed to test this hypothesis.

LIMITATIONS

The primary limitations to this study are the use of the self-selection model for data collection and the low response rate to the questionnaire based on the uses of the system. This response rate is not unusual in the health care environment, in which time is a critical variable, and nonessential activities receive low priority. Another limitation was the potential for introducing bias by reminding the participants during training that data was needed to prove efficacy of the project to support continuation.

The structured interview component was designed to validate research findings from the questionnaires and to broaden the population to include those not trained. However, specific identification of a potential sample was limited by lack of a mechanism to track specific user access, except the users of MD Consult, and only one health care provider, a physician, was identified by this method and interviewed. This hardly constituted a representative sample of the untrained population of users, and no statistical inference can be drawn from nineteen interviews.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARIANS

Both the Marshall [9] and the Klein [10] studies demonstrated that information services provided by hospital librarians in support of clinical decision making had a significant impact on health care outcomes. The intervention in both of these studies was the librarians providing high-quality information in a timely manner. Both studies were done in metropolitan areas in hospitals that had both libraries and trained librarians to provide the services.

Conversely, there are many parts of the country in which such ready access to quality information services provided by trained librarians is not feasible. Areas with few health care providers, whether those areas are rural with low population densities or urban inner cities, are virtually unable support an onsite, trained health information professional. However, the need for quality information services is growing, and the potential impact of such services on health care outcomes has been demonstrated. As demonstrated in this study, health professionals with access to a hospital library appreciate the convenience of the virtual medical library as much as those without a professional library.

Computers are becoming ubiquitous to medical practice, regardless of location or relative wealth of the local health care community. Therefore, to ensure that all health care providers have equal access to necessary information to support their decision making, it is necessary to explore new ways of delivering that information in an efficient and effective manner. This need challenges librarians to reengineer their practices for delivering such information.

Librarians have always been experts at identifying and organizing information for their libraries, which in turn support their ability to deliver information services to their clients. In a virtual library, these skills are critically important. The primary difference is that the information is electronic, and the library locus is a Website or some other means of ready access for the client.

Just as bibliographic instruction is essential to assist library clients in the optimum use of the physical library, instruction in the use of the virtual library is important. Potential virtual library users will frequently cross disciplines and bring diverse backgrounds to their need for information to support decision making. This challenges health sciences library educators to develop new instructional modalities to ensure that all potential virtual library clients are given the knowledge and skills to make them effective in accessing appropriate information resources.

Just as the health care community has specialists, there is still the need for skilled information specialists to provide information at times when the information generalist, regardless of medical specialty, needs tertiary information consultation. However, access to a high-quality virtual library, one developed and organized by a health information professional, and targeted training in the use of the virtual library by the health information professional should lessen the need for such on-demand tertiary information consultation.

The need for high-quality health information professionals or librarians is not diminishing. However, their roles in the pervasive digital environment will change. If librarians do not seize this growing opportunity to address critical information needs, then for-profit medical Web companies will fill the void, and neither the medical library profession nor health information professionals will be well served.

CONCLUSION

A number of studies have been done on the impact of library services on a variety of health care outcomes. Most of these studies have centered on librarians providing quality-filtered information to health care providers. However, it is unrealistic to expect the availability of a health information professional each time an information need is identified. To address this issue, the concept of a virtual library, with appropriate training in its use, has proved to be a viable option.

The impact in terms of health care outcomes of the virtual library project was comparable to the aforementioned Marshall study. Two elements of the virtual library project contributed to its success. The first was identifying and organizing appropriate electronic resources, which would support clinical decision making. The second was the training offered to facilitate use of the resources. The results of this project, the growing availability of the Internet in even the most remote areas of this country, and the changing health care market place suggest the need for health information professionals to position themselves for next generation library services.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Deborah Kellenburger, RN, M.I.S., in this project.

Footnotes

* This program was supported by NIH Grant no. 1-G07-LM06611-01A1 from the National Library of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- Marshall JG. The impact of the hospital library on clinical decision making: the Rochester study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1992 Apr; 80(0):169–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MS, Ross FV, Adams DL, and Gilbert CM. Effect of online literature searching on length of stay and patient care costs. Acad Med. 1994 Jun; 69(0):489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham JF, Perry M. Promotion of health information access via Grateful Med and Loansome Doc: why isn't it working? Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1996 Oct; 84(0):498–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsch JL. Equalizing rural health professionals' information access: lessons from a follow-up outreach project. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Jan; 85(0):39–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsch JL, Landwirth TK. Document needs in a rural GRATEFUL MED outreach project. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994 Oct; 82(0):357–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dee C, Blazek R. Information needs of the rural physician: a descriptive study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1993 Jul; 81(0):259–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dee C, Blazek R. Information needs of the rural physician: a descriptive study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1993 Jul; 81(0):263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JG. The impact of the hospital library on clinical decision making: the Rochester study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1992 Apr; 80(0):169–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JG. The impact of the hospital library on clinical decision making: the Rochester study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1992 Apr; 80(0):169–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MS, Ross FV, Adams DL, and Gilbert CM. Effect of online literature searching on length of stay and patient care costs. Acad Med. 1994 Jun; 69(0):489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]