Abstract

Background

In order to optimise the cost-effectiveness of active surveillance to substantiate freedom from disease, a new approach using targeted sampling of farms was developed and applied on the example of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) and enzootic bovine leucosis (EBL) in Switzerland. Relevant risk factors (RF) for the introduction of IBR and EBL into Swiss cattle farms were identified and their relative risks defined based on literature review and expert opinions. A quantitative model based on the scenario tree method was subsequently used to calculate the required sample size of a targeted sampling approach (TS) for a given sensitivity. We compared the sample size with that of a stratified random sample (sRS) with regard to efficiency.

Results

The required sample sizes to substantiate disease freedom were 1,241 farms for IBR and 1,750 farms for EBL to detect 0.2% herd prevalence with 99% sensitivity. Using conventional sRS, the required sample sizes were 2,259 farms for IBR and 2,243 for EBL. Considering the additional administrative expenses required for the planning of TS, the risk-based approach was still more cost-effective than a sRS (40% reduction on the full survey costs for IBR and 8% for EBL) due to the considerable reduction in sample size.

Conclusions

As the model depends on RF selected through literature review and was parameterised with values estimated by experts, it is subject to some degree of uncertainty. Nevertheless, this approach provides the veterinary authorities with a promising tool for future cost-effective sampling designs.

Background

Documented freedom from disease is the basis for international free trade of animals and animal products. In Switzerland, annual serological surveys are conducted to substantiate freedom from infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR), enzootic bovine leucosis (EBL), Brucella melitensis, Aujeszky's disease and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS). Switzerland is free of IBR and EBL since 1994. Therefore, a very low prevalence is considered for sample size calculation and, in consequence, a large sample size is required to demonstrate freedom from disease [1]. Thus, this active surveillance approach is costly and personnel-intensive. The development of cost-effective tools for animal disease surveillance is therefore of high interest to scientists and decision-makers in the field of veterinary public health.

One approach to increase the efficiency of active surveillance is targeting high-risk strata in the animal population, termed risk-based surveillance, or in the context of this manuscript called targeted sampling (TS). It is based on the identification and utilisation of specific, scientifically documented quantitative risk factors for occurrence of the respective diseases [2]. In conventional approaches to document disease freedom, a sample of farms is selected randomly from a central database. Randomness is necessary to ensure representativeness for induction on the population. Random sampling can be done in strata without violating the assumption of representativeness. However, random sampling does not take into account uneven distribution of disease risk. Thus, it is the best choice only in absence of information on the distribution of disease risk. When such information is available, this can be used to formulate risk strata. Consequently, testing high-risk strata offers a potential of detecting disease with a higher probability or a smaller sample size compared to testing non high-risk strata [2].

The aims of our study were to evaluate the performance and cost-effectiveness of a TS approach compared with conventional stratified random sampling (sRS) using stochastic scenario tree modelling [1,3]. Our study diseases for this task were IBR and EBL in Swiss cattle, the freedom of which we wanted to demonstrate at a maximum herd prevalence of 0.2% with an overall sensitivity of 99% [4]. Within the scope of this paper, the level of confidence yielded by a surveillance system is referred to as its sensitivity.

Methods

Evaluation of risk factors for IBR and EBL

The first step of the study consisted in identifying relevant risk factors (RF) for disease occurrence on individual cattle farms. A literature review on the epidemiology of IBR and EBL was conducted with a focus on specific RF for the diseases and their relevance for the Swiss cattle population, given that the population is considered to be free of these diseases. Lists of RF were generated and discussed with national experts within the field resulting in a final, strongly condensed selection of RF for both diseases (Table 1). As all cattle farms are registered in the animal movement database (TVD), the chosen RF could be allocated to the affected farms by means of the TVD and the geographical software ArcGis 9, ArcMap Version 9.2 (ESRI Inc.) providing us with an Excel list (Microsoft Corporation 2007) of all 52,176 Swiss cattle farms and their corresponding RF for IBR and EBL for the year 2008.

Table 1.

Risk factors for the introduction of IBR and EBL into Swiss cattle farms

| Risk factor (RF) | Farms exposed to RF | Definition of the risk involved |

|---|---|---|

| IBR | ||

| Animal contacts (AC) | All farms which send their cattle, or part of it, to summer pastures (inside the country or across the border) and/or let their bovines participate in cattle shows | Physical contacts with potentially infected bovines from other farms |

| Higher-than-average animal movements on farm (AM) | All farms having more cattle entries on farm per year than the yearly median value for their herd size category | Farms which purchase many bovines from outside have a higher risk of getting an IBR-positive animal into their herd than farms which do not purchase any cattle |

| Farm close to the border with another country (FcB) | All cattle farms situated up to 5 km from the Swiss border and 500 m at most from a larger road (in this zone) | Uncontrolled contacts between potentially infected animals; airborne transmission of pathogens; veterinarians from neighbouring countries treating cattle (having contact with potentially IBR-infected animals); facilitated illegal importation of bovines |

| High density of cattle farms in the vicinity (hDH) | All farms that have many (in our case >21) neighbouring farms within a radius of 1 km around their farm | Uncontrolled contacts between animals (over fences), or between animals and persons (neighbouring families, visitors...) |

| Importation of cattle (IC) | All farms having imported cattle in their herds | Even though cattle destined for importation must originate from IBR-free herds, or, in the case of non-IBR-free countries, have to be tested for IBR, an introduction of the disease through cattle importation can never be excluded |

| EBL | ||

| Higher-than-average animal movements on farm (AM) | All farms that have more cattle entries on farm per year than the yearly median value for their herd size category | Farms which purchase many bovines from outside, have a higher risk of getting an EBL-positive animal in their herd than farms which do not purchase any cattle |

| Importation of cattle (IC) | All farms having imported cattle in their herds | Even though cattle destined for importation must originate from EBL-free herds, or, in the case of non-EBL-free countries, have to be tested for EBL, an introduction of the disease through cattle importation can never be excluded |

| Summer pasture with animals from other herds (SP) | All farms which send their cattle, or part of it, on summer pastures (inside the country or across the border) | This risk factor implicates lengthy physical contacts between animals from different herds and therefore makes a transmission of EBL from one bovine to another possible; cattle are exposed to biting and stinging insects in the summer season (→ transmission of infected lymphocytes) |

To allow quantitative comparison of information content or gain of RFs - either single or combined - these had to be parameterised. To allocate values to the selected RF, we chose a modified Delphi approach for the gathering of expert opinion [5]. An electronic questionnaire, seeking estimations on the minimum, the most likely and the maximum values of relative risks (RR) for the selected RF (i.e. the expert-based change in disease risk compared to a baseline RF level) was sent to 15 experts in the field of veterinary epidemiology, veterinary virology and veterinary public health. We formulated the questions without giving a desired range for the RR values. Thus, the experts were boundless free to name their estimates. The same questionnaire, supplemented with the median values of all RR estimates from the first round was sent to the experts a second time, offering them the possibility to either adjust their estimates for the RR or to confirm their previous values. The final results considered for the parameterisation of the RF were the median values of all estimates from the second questioning round.

Adaptation and development of the scenario tree model

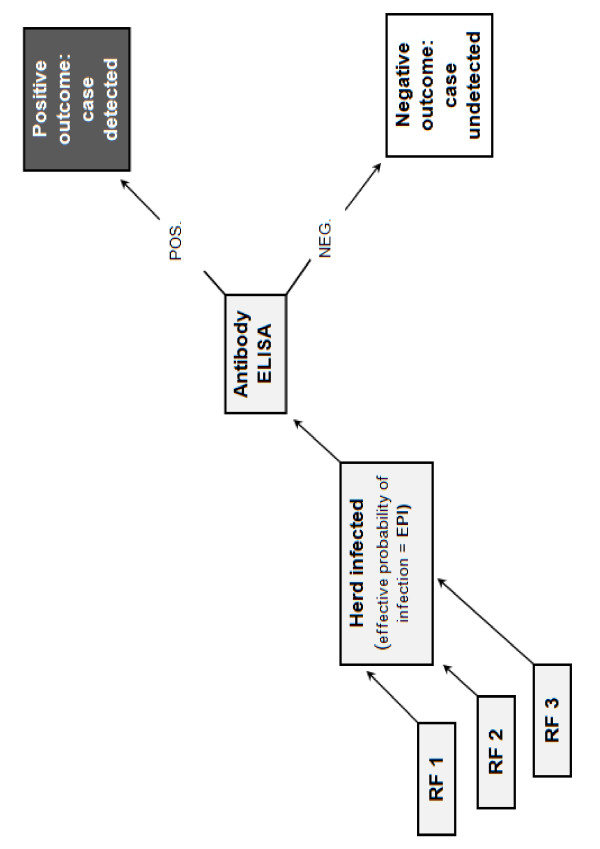

A scenario tree models the process of disease detection through a surveillance system component (SSC), tracing the probabilities that a single unit (eg. farm) will yield either a positive or a negative outcome. The tree includes all factors affecting the probability of infection or detection of a surveillance unit (Figure 1). Scenario tree modelling is used to calculate the sensitivity of a SSC for a given design prevalence and sample size [3].

Figure 1.

Conceptual schematic of the scenario tree for the annual serological survey to demonstrate freedom from EBL in Switzerland. For IBR, the same procedure applies, but with 5 instead of 3 risk factors (RF).

The scenario tree models described in literature so far are mostly used to calculate the sensitivity of a SSC for a given sample size and design prevalence [1,3]. In our use of the scenario tree method, we also aimed at calculating a sample size to demonstrate disease freedom for a given sensitivity and at a given prevalence. Hence, the SSC evaluated in our study was the annual serological survey for IBR and EBL. We also wanted to determine the risk factor combinations (eq. risk strata) that yielded the highest information gain, so as to choose as many farms as possible from these high-risk strata and, in consequence, keep the sample size minimal. We parameterised two models (one for IBR, one for EBL) using the corresponding data for the respective diseases and modelled two sampling scenarios, one hypothetical and one practical, for each disease.

Input parameters

In the scenario tree model, we used a design prevalence at the herd level (P*H) of 0.2% for both IBR and EBL (Table 2). We defined the proportions (PrRF) of the selected risk factors for Swiss cattle farms as well as their RR (RRRF) (Table 2) for the calculation of the adjusted risks and the effective probabilities of infection (EPI) for each combination of risk factors and hence, every single farm [1,3]. The medians of the minimum, the most likely and the maximum values for the RR determined through expert opinion were modelled as pert distributions in @Risk 5.0 (Palisade Corporation) and run with 1000 iterations. The test sensitivities for the antibody-ELISAs (CHEKIT® Trachitest Serum, IDEXX Laboratories and CHEKIT® Leucose Serum, IDEXX Laboratories) used for the annual serological surveys in Switzerland were set at 99.3% for IBR and 99.9% for EBL. These values were obtained from the Swiss reference laboratories for IBR and EBL (Table 2). All animals per herd are tested and a herd is already classified positive if only one single sample shows a positive reaction. Therefore, the values for the herd sensitivities are equal to the values of the diagnostic test (= single unit) sensitivities. The specificity of both ELISA-tests was set at 100%, since Switzerland is free of both diseases and every positive test result would consistently be retested with additional diagnostic tests until confirmed positive or negative. Therefore, the model does not account for false positive results.

Table 2.

Input parameters used in the scenario tree model to substantiate freedom from IBR and EBL in Switzerland

| Description of input parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Herd-level design prevalence for disease freedom from IBR and EBL (P*H) | 0.002 | OIE Animal Health Code 2010 |

| Proportions of risk factors for IBR in the cattle farm population (PrRF) | ||

| Proportion of "animal contacts" (PrAC) | 0.401 | TVD1 |

| Proportion of "animal movements" (PrAM) | 0.286 | TVD1 |

| Proportion of "farm close to border" (PrFcB) | 0.100 | TVD1 |

| Proportion of "high density of herds" (PrhDH) | 0.123 | TVD1 |

| Proportion of "importation of cattle" (PrIC) | 0.002 | TVD1 |

| Proportions of risk factors for EBL in the cattle farm population (PrRF) | ||

| Proportion of "animal movements" (PrAM) | 0.286 | TVD1 |

| Proportion of "importation of cattle" (PrIC) | 0.002 | TVD1 |

| Proportion of "common summer pasture" (PrSP) | 0.398 | TVD1 |

| Relative risks (RRRF) of risk factors for IBR | ||

| RR of "animal contacts" (RRAC) | RiskPert(2; 4; 6) | Expert opinion2 |

| RR of "animal movements" (RRAM) | RiskPert(2; 4; 6) | Expert opinion2 |

| RR of "farm close to border" (RRFcB) | RiskPert(2; 4; 6) | Expert opinion2 |

| RR of "high density of herds" (RRhDH) | RiskPert(1; 2; 3) | Expert opinion2 |

| RR of "importation of cattle" (RRIC) | RiskPert(2; 4; 6) | Expert opinion2 |

| Relative risks (RRRF) of risk factors for EBL | ||

| RR of "animal movements" (RRAM) | RiskPert(1; 2; 3) | Expert opinion2 |

| RR of "importation of cattle" (RRIC) | RiskPert(1.5; 4; 5) | Expert opinion2 |

| RR of "common summer pasture" (RRSP) | RiskPert(1; 1.5; 3) | Expert opinion2 |

| ELISA test-sensitivities for herd serology (TSensSH) | ||

| TSensSH of IBR-Antibody-ELISA (CHEKIT® Trachitest Serum, IDEXX Laboratories) | 0.993 | Swiss Reference Laboratory for IBR3 |

| TSensSH of EBL-Antibody-ELISA (CHEKIT® Leucose Serum, IDEXX Laboratories) | 0.999 | Swiss Reference Laboratory for EBL4 |

1Swiss Animal Movement Database (2008)

2Modified Delphi approach

3Institute of Virology, University of Zurich

4Institute of Veterinary Virology, University of Berne

Model Outputs

With the adapted scenario tree model, we were able to calculate the sensitivity of a certain targeted risk stratum using the following equation described by Martin et al. [3]:

| (1) |

where CSe (component sensitivity) is the sensitivity of a certain risk stratum, SUSe (system unit sensitivity) corresponds to the average probability that one randomly selected farm out of a certain risk stratum will yield a positive outcome, given that the country is infected at P*H. SUSe is calculated by summing up the limb probabilities for all limbs with positive outcomes in the scenario tree model.

The sample size n for conducting a random sample or a targeted sample in a certain risk stratum required to reach a given sensitivity CSe can be calculated by solving equation (1) for n:

| (2) |

As we were interested in calculating a sample size containing farms from different, especially high-risk strata, we needed to combine the CSe of several targeted risk strata to an overall SSe (system sensitivity) for all selected risk strata. This was done using the following equation described by Martin et al. [3]:

| (3) |

where J denotes the number of risk strata considered and CSej corresponds to the sensitivity for the j-th risk stratum.

(a) Using exclusive targeted sampling

For both diseases, a theoretical scenario involving solely TS in the highest risk stratum was modelled. In this scenario, only farms possessing all RF for the respective diseases, meaning that they were classified in the risk stratum with the greatest information gain, were considered for sampling. However, this implies that enough farms comprising each of the studied RF must exist, which, in reality was not the case. Exclusive TS in a practical sampling scenario is also possible. However, this means that farms from several risk strata would have to be considered for testing. The reduction in sample size would then be smaller than in the hypothetical scenario mentioned above, where only farms from the highest risk stratum are considered.

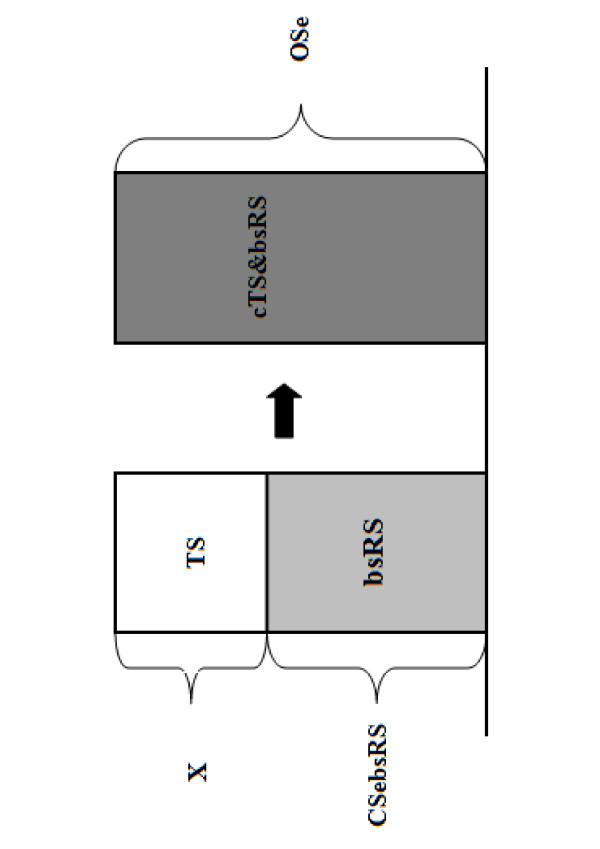

(b) Combining targeted and random sampling in one sampling scheme

In order to make use of the information gain of TS but without compromising the representativeness of the survey with a very small targeted sample size, we combined TS with a baseline stratified random sample (bsRS). This combined approach cTS&bsRS is conducted as follows: First, the sensitivity of a bsRS has to be determined. In our example, we decided to conduct a bsRS with a sensitivity of 90%. The sample size for the bsRS was calculated using equation (2) and instead of targeting a certain risk stratum, we ran the scenario tree model distributing the PrRF as they appear in the population, so as to obtain a sample chosen randomly out of all risk strata.

In order to reach the overall sensitivity (OSe) of 99% for the documentation of freedom from disease, the required SSe for the TS component can be calculated using the following formula, modified from Hadorn et al. [6]:

| (4) |

where x is the required SSe for the TS component, OSe the required overall sensitivity of cTS&bsRS and CSebsRS the sensitivity of the baseline random sample (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual schematic representing the process of combining targeted sampling with baseline random sampling to substantiate freedom from disease. TS is the targeted sampling component, bsRS denotes the baseline stratified random sampling component with the sensitivity CSebsRS, cTS&bsRS is the combination of targeted and random sampling, OSe is the required overall sensitivity to demonstrate freedom from disease and X represents the sensitivity of the TS component, the value of which can be calculated using eq. (4).

Analysis of cost-effectiveness

To compare the cost-effectiveness of the cTS&bsRS approach with that of sRS, we identified the differences in each step of the planning and implementation of the annual serological surveillance programme for the two methods. We then determined the costs linked to each step of the programme, based on already available data from the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office (FVO) (unpublished data: Sonia Menéndez, "Costs of surveillance systems (2008)", Monitoring Department, Federal Veterinary Office) and compared the resulting full survey costs for both approaches.

In Switzerland, all cattle over two years of age on selected survey farms are tested for IBR and EBL [7]. In order to get an estimate of cost for budgeting, we calculated the net costs of the samples (material and analysis) for the average number of individual animals to be tested per farm at 20 for randomly selected farms (which corresponds to the long-time average [7]), and in targeted selected farms at 30 animals per farm due to the larger average herd sizes in "risk farms" (corresponding to an average of 30 animals per farm, as deduced from our data). The detailed effective costs have to be calculated at the end of the survey.

Results

Evaluation of risk factors for IBR and EBL

As a result of the literature review and expert opinion survey, we identified the five following relevant RF for the introduction of IBR into Swiss cattle farms together with the corresponding sets of minimum, most likely and maximum values for their RR (in brackets): animal contacts (2/4/6), over-average animal movements (2/4/6), farm close to the border (2/4/6), importation of cattle (2/4/6) and high density of herds in the vicinity (1/2/3) (Table 1) [8-27]. With five RF and two possible outcomes (yes/no) each, we could generate 32 (= 25) possible different combinations of RF, meaning that we had 32 risk strata for IBR available in the scenario tree model. As a result, we could assert that ~ 40% (20,870) of all cattle farms had no RF for IBR, whereas only one farm (~ 0.002%) had all five RF for the disease.

For EBL, the following three RF were determined, together with the corresponding sets of minimum, most likely and maximum values for their RR (in brackets): importation of cattle (1.5/4/5), over- average animal movements (1/2/3), and summer pasture with other herds (1/1.5/3) (Table 1) [28-45]. With three risk factors and two possible outcomes, we could generate 8 (= 23) different risk strata for the EBL model. ~51.5% (26,870) of all cattle farms had no RF for EBL, while ~ 0.07% (40) of the farms had all three RF applying to them.

Adaptation and development of the scenario tree model

(a) Using exclusive targeted sampling

The theoretical sample sizes of the scenario involving solely TS in the highest risk stratum ranged from 21 to 58 farms (yielding a 99% sensitivity on the 95%- and 5%-percentile, respectively, on the distribution for CSe) for IBR and 208 to 486 farms (95%- and 5%-percentile, respectively) for EBL.

(b) Combining targeted and random sampling in one sampling scheme

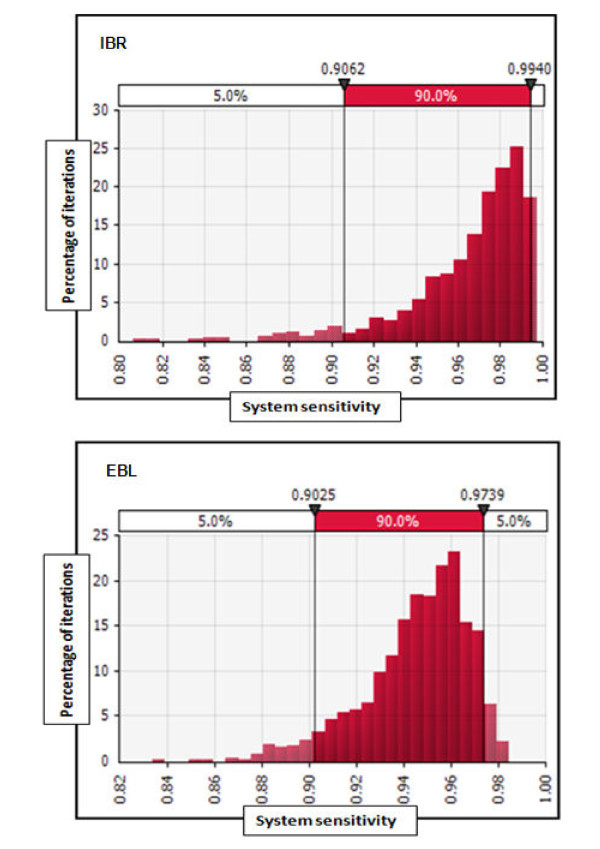

The sample sizes for bsRS resulted in 1,158 and 1,150 farms for IBR and EBL, respectively. The difference of 8 farms between IBR and EBL is explained by the difference in the test sensitivity for the two diseases (Table 2). The SSe required for the TS component calculated with equation 4 accounted for 90% in order to reach an OSe of 99% (Figure 2). The sample sizes for the TS component selected out of the highest risk strata for the respective diseases consisted of 83 farms for IBR and 600 farms for EBL in order to yield 90% sensitivity on the 5%-percentile. We used the results on the 5%-percentile as a conservative approach in defining the sample sizes for the TS component (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of the system sensitivity (SSe) of the targeted sampling component (TS) for IBR (n = 83 farms) and EBL (n = 600 farms).

For sampling, the farms, as they actually existed in reality, were successively selected out of the highest risk strata until the required SSe was reached. For IBR, this resulted in: the only farm out of the highest risk stratum with all RF present; all of the two farms out of the stratum with the RF AC, AM, FcB and IC present and 80 farms out of 125 actually available farms in the stratum with the RF AC, AM, FcB, and hDH present. For EBL this resulted in: all of the 40 farms out of the highest risk stratum with all RF present; all of the 18 farms out of the risk stratum with RF AM and IC; all of the 8 farms out of the risk stratum with RF SP and IC; all of the 34 farms out of the risk stratum with the RF IC and 500 farms out of actually 10,439 available farms of the risk stratum with RF SP and AM present.

Using cTS&bsRS, the total minimal sample sizes required were therefore 1,241 herds for IBR and 1,750 herds for EBL on the 5%-percentile. In comparison, a sRS with an overall sensitivity of 99% calculated with the software Freecalc (Moffsoft™) and using the test sensitivities mentioned in Table 2 consisted of 2,259 farms to be tested for IBR and 2,243 farms to be tested for EBL.

Analysis of cost-effectiveness

The annual serological survey for IBR and EBL in Switzerland is planned and conducted by the FVO in Berne. The samples are then collected by official veterinarians in the Regional Veterinary Offices (RVO, cantons) and sent to different diagnostic laboratories approved by the FVO for analysis. In case positive results are detected, samples are sent to the reference laboratories for IBR or EBL for confirmatory analysis. The evaluation and reporting of the results of the survey is again carried out by the FVO. The process of planning and implementation of the survey is basically identical for both cTS&bsRS and sRS. However, cTS&bsRS requires additional administrative effort and expenses for the annual updating of the RF per farm.

Using the values for the number of blood samples to be collected mentioned in the methods section, 25,650 individual blood samples were needed to substantiate freedom from IBR and 41,160 samples to demonstrate freedom from EBL using cTS&bsRS. Conventional sRS would require 45,180 individual blood samples to be tested for IBR and 44,860 samples for EBL.

The total costs for an IBR survey using cTS&bsRS amounted to 580,600 € (exchange ratio CHF/€ = 1.5), while a sRS cost 964,800 €. The total expenses for an EBL survey using cTS&bsRS added up to 880,100 €, while a sRS cost 955,900 € (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of costs for the annual serological survey to substantiate freedom from IBR and EBL using conventional stratified random sampling (sRS) and combined targeted and baseline stratified random sampling (cTS&bsRS) (figures based on data by S. Menéndez, Swiss Federal Veterinary Office (2008), exchange ratio CHF/€ = 1.5)

| Number of herds to be tested |

Number of individual blood samples |

Costs for the planning of the survey | Costs for sampling and laboratory analysis |

Total costs for the full survey5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBR | |||||

| sRS | 2,259 | 45,1801 | 8,700 € | 912,000 € | 964,800 € |

| cTS&bsRS | 1,241 | 25,6502 | 11,800 €3 | 524,500 € | 580,600 € |

| EBL | |||||

| sRS | 2,243 | 44,8601 | 8,700 € | 903,100 € | 955,900 € |

| cTS&bsRS | 1,750 | 41,1602 | 11,800 €3 | 824,000 € | 880,100 € |

1 The average number of animals to be tested (eq. individual samples) per farm was set at 20 for randomly selected farms.

2 The average number of animals to be tested (eq. individual samples) per farm was set at 30 for farms selected targeted and at 20 for farms selected randomly (baseline sample).

3Additional administrative expenses for updating of "risk farms".

4 The costs include farm visits, sampling labour and material, shipment/postage expenses and laboratory costs.

5 The costs for the evaluation and reporting of the survey results do not differ between the two methods and are therefore not mentioned separately in the table, but are included in the total costs of the survey.

Discussion

With the approach described in this paper, we developed a user-friendly instrument for the design of risk-based sampling programmes, providing veterinary authorities with a promising tool for future, cost-effective sampling strategies. Taking the gain in information of testing high-risk strata into account, we are able to considerably reduce the sample size. Especially for IBR, a reduction by almost half of the samples was achieved. We explain this fact by the larger number of relevant RF identified and the higher values for their respective RR compared to EBL. Another influential factor in this context is the larger number of farms available in the highest risk strata for IBR compared to EBL. The analysis of cost-effectiveness clearly revealed a financial benefit of cTS&bsRS, when compared to exclusive sRS for both IBR and EBL.

In the case of the theoretical scenario involving solely TS in the highest risk stratum, the reduction in sample size compared to sRS would be major. However, this scenario is hypothetical and based on the assumption that we have a large number of farms available in the highest risk stratum, which in reality is not the case. Nevertheless, it would be possible to conduct solely TS by considering all available farms in the different risk strata with the highest information gain and consequently to further decrease the necessary sample size. But the eventual geographical clustering of an entirely targeted sample due to uneven spread of risk would be a disadvantage in terms of representativeness and coverage of a survey in many regions or countries. The proposed approach of cTS&bsRS assures the representativeness of the survey, while at the same time taking into account the advantages of TS.

The stochastic scenario tree model to calculate CSe or n of the TS component depends on RF selected through literature review, parameterised with estimates based on expert opinion and is therefore subject to some degree of uncertainty. However, the distributions used for the RR and in consequence, consideration of conservative results on the 5%-percentile of the distribution for the CSe of TS provides a certain counterbalance for this issue. A survey based on cTS&bsRS guarantees an OSe of at least over CSebsRS in case the estimations for the RF and RR should have been completely inadequate. Furthermore, the percentage of CSebsRS on the OSe and therefore the degree of uncertainty can be varied and defined according to requirements. It has to be noted that correlation or dependence between RF was not considered in this study. The participants of the expert opinion survey were left free to assign any value to the RR of the evaluated RF. Although it is possible that experts intuitively considered some degree of correlation or dependence between RF, this issue was not addressed in the survey design.

Because a classical validation of a model with reliable field data is nearly impossible for rare diseases, we chose to verify the accuracy of our RF for IBR with past, well documented cases of the disease [46,47]. All of the three Swiss IBR outbreak farms from the canton of Jura in 2009 had at least one RF applying to them. One farm even had four RF. Consequently, those farms would have a high probability of being selected for a survey based on cTS&bsRS. For EBL however, even this attempt of validation was difficult to achieve, as only very few, poorly documented cases of leucosis actually occurred in Switzerland since the eradication of the disease.

Further surveillance components for IBR and EBL in Switzerland, such as passive clinical surveillance, slaughterhouse inspection and abortion examination, were not taken into account in this project as we aimed at analysing the legally prescribed annual serological survey only.

Additionally, we simulated and analysed the effect of varying input parameters on the SSC and directly explored the effects of several exchangeable parameters on the OSe. We did this using different values for PrRF and RRRF and checking if the scenario tree model produced logical results.

The problem of testing the same farms year by year can be reduced by a yearly updating of the risk factors per farm. This is a recommended procedure anyway, as RF for the cattle farms can change over time. More importantly, the bsRS has a certain compensational function also in this respect. Furthermore, if a large number of farms are available in a selected high risk stratum, the farms can be selected randomly within this risk stratum, and not all farms of a certain risk stratum would have to be tested. A verification of the accuracy of and, in consequence, updating of the RF and the RR in regular time intervals (i.e. every 5 years) is also a strategy to consider.

The different approaches described in this paper are all based on whole herd testing which corresponds to the sampling framework of IBR and EBL in Switzerland to demonstrate absence of disease on the farm level. However, the model described in this paper can also be modified for diseases with increased within-herd prevalence. For such diseases, the within-herd prevalence has to be included as an additional infection node in the scenario tree model.

Conclusions

Combined targeted and baseline stratified random sampling is a cost-effective approach for the substantiation of disease freedom and therefore has a potential to be implemented in the annual serological surveys for IBR and EBL in Switzerland. The scenario tree model described in this study can be modified, extended and further developed in order to fit other diseases and objectives for targeted surveillance in Switzerland and other countries.

Authors' contributions

SB conducted the study and wrote the manuscript. HS participated in the design of the study, provided substantial support in the collection of data related to the risk factors, helped to supervise the work and to draft the manuscript. ME provided valuable expertise and support on the studied viruses and critically revised the manuscript. MR provided substantial support in the analysis of data related to the risk factors, helped to supervise the work and to draft the manuscript. MGD helped to draft the manuscript and co-supervised the doctoral thesis in the framework of which the manuscript was written. DCH designed the study, was the main supervisor of the work and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sarah Blickenstorfer, Email: sarah.blickenstorfer@ymail.com.

Heinzpeter Schwermer, Email: heinzpeter.schwermer@bvet.admin.ch.

Monika Engels, Email: monika.engels@vetvir.uzh.ch.

Martin Reist, Email: martin.reist@vphi.unibe.ch.

Marcus G Doherr, Email: marcus.doherr@vphi.unibe.ch.

Daniela C Hadorn, Email: daniela.hadorn@bvet.admin.ch.

Acknowledgements

We thank the colleagues at the Federal Veterinary Office and the Veterinary Public Health Institute, especially Michael Binggeli, Patrick Presi, Marco Sievi and Ulrich Weber for their help in collecting and analysing data, especially related to the risk factors, cattle farms and survey costs. We also thank all participants of the modified Delphi expert opinion survey for their valuable support in the study. This project was funded by the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office.

References

- Hadorn DC, Stark KD. Evaluation and optimization of surveillance systems for rare and emerging infectious diseases. Vet Res. 2008;39(6):57. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2008033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark KD, Regula G, Hernandez J, Knopf L, Fuchs K, Morris RS, Davies P. Concepts for risk-based surveillance in the field of veterinary medicine and veterinary public health: review of current approaches. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PA, Cameron AR, Greiner M. Demonstrating freedom from disease using multiple complex data sources 1: a new methodology based on scenario trees. Prev Vet Med. 2007;79(2-4):71–97. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agreement between the European Community and the Swiss Confederation on trade in agricultural products, in: Annex 11, Appendix2. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:352:0024:0030:EN:PDF

- Anonymous. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delphi_method

- Hadorn DC, Rufenacht J, Hauser R, Stark KD. Risk-based design of repeated surveys for the documentation of freedom from non-highly contagious diseases. Prev Vet Med. 2002;56(3):179–192. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(02)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FVO Annual report on freedom from disease 2009. http://www.bvet.admin.ch/gesundheit_tiere/00314/index.html?lang=de

- Ackermann M, Müller HK, Bruckner L, Kihm U. Eradication of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis in Switzerland: review and prospects. Vet Microbiol. 1990;23(1-4):365–370. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90168-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann M, Engels M. Pro and contra IBR-eradication. Vet Microbiol. 2006;113(3-4):293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelaert F, Speybroeck N, de Kruif A, Aerts M, Burzykowski T, Molenberghs G, Berkvens DL. Risk factors for bovine herpesvirus-1 seropositivity. Prev Vet Med. 2005;69(3-4):285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brülisauer F, Thoma R, Cagienard A, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Lutz H, Meli ML, Regula G, Jorger K, Perl R, Dreher UM. et al. Anaplasmosis in a Swiss dairy farm: an epidemiological outbreak investigation. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2004;146(10):451–459. doi: 10.1024/0036-7281.146.10.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels M, Ackermann M. Pathogenesis of ruminant herpesvirus infections. Vet Microbiol. 1996;53(1-2):3–15. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(96)01230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage JJ, Vellema P, Schukken YH, Barkema HW, Rijsewijk FA, van Oirschot JT, Wentink GH. Sheep do not have a major role in bovine herpesvirus 1 transmission. Vet Microbiol. 1997;57(1):41–54. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage JJ, Schukken YH, Schols H, Maris-Veldhuis MA, Rijsewijk FA, Klaassen CH. Transmission of bovine herpesvirus 1 within and between herds on an island with a BHV1 control programme. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;130(3):541–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars MH, Bruschke CJ, van Oirschot JT. Airborne transmission of BHV1, BRSV, and BVDV among cattle is possible under experimental conditions. Vet Microbiol. 1999;66(3):197–207. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(99)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars MH, de Jong MC, van Maanen C, Hage JJ, van Oirschot JT. Airborne transmission of bovine herpesvirus 1 infections in calves under field conditions. Vet Microbiol. 2000;76(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(00)00218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollema L, Rijsewijk FA, Nodelijk G, de Jong MC. Quantification of the transmission of bovine herpesvirus 1 among red deer (Cervus elaphus) under experimental conditions. Vet Microbiol. 2005;111(1-2):25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muylkens B, Thiry J, Kirten P, Schynts F, Thiry E. Bovine herpesvirus 1 infection and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis. Vet Res. 2007;38(2):181–209. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuotio L, Neuvonen E, Hyytiainen M. Epidemiology and eradication of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis/infectious pustular vulvovaginitis (IBR/IPV) virus in Finland. Acta Vet Scand. 2007;49:3. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-49-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylin B, Madsen KG, Ronsholt L. Reintroduction of bovine herpes virus type 1 into Danish cattle herds during the period 1991-1995: a review of the investigations in the infected herds. Acta Vet Scand. 1998;39(4):401–413. doi: 10.1186/BF03547766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis-Calderon JJ, Segura-Correa VM, Segura-Correa JC, Alvarado-Islas A. Seroprevalence of and risk factors for infectious bovine rhinotracheitis in beef cattle herds of Yucatan, Mexico. Prev Vet Med. 2003;57(4):199–208. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(02)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiry J, Keuser V, Muylkens B, Meurens F, Gogev S, Vanderplasschen A, Thiry E. Ruminant alphaherpesviruses related to bovine herpesvirus 1. Vet Res. 2006;37(2):169–190. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik G, Dijkhuizen AA, Huirne RB, Schukken YH, Nielen M, Hage HJ. Risk factors for existence of Bovine Herpes Virus 1 antibodies on nonvaccinating Dutch dairy farms. Prev Vet Med. 1998;34(2-3):125–136. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(97)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik G, Schukken YH, Nielen M, Dijkhuizen AA, Benedictus G. Risk factors for introduction of BHV1 into BHV1-free Dutch dairy farms: a case-control study. Vet Q. 2001;23(2):71–76. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2001.9695085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik G, Schukken YH, Nielen M, Dijkhuizen AA, Barkema HW, Benedictus G. Probability of and risk factors for introduction of infectious diseases into Dutch SPF dairy farms: a cohort study. Prev Vet Med. 2002;54(3):279–289. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(02)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wuijckhuise L, Bosch J, Franken P, Frankena K, Elbers AR. Epidemiological characteristics of bovine herpesvirus 1 infections determined by bulk milk testing of all Dutch dairy herds. Vet Rec. 1998;142(8):181–184. doi: 10.1136/vr.142.8.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik G, Dijkhuizen AA, Huirne RB, Benedictus G. Adaptive conjoint analysis to determine perceived risk factors of farmers, veterinarians and AI technicians for introduction of BHV1 to dairy farms. Prev Vet Med. 1998;37(1-4):101–112. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(98)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acaite J, Tamosiunas V, Lukauskas K, Milius J, Pieskus J. The eradication experience of enzootic bovine leukosis from Lithuania. Prev Vet Med. 2007;82(1-2):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech-Nielsen S, Piper CE, Ferrer JF. Natural mode of transmission of the bovine leukemia virus: role of bloodsucking insects. Am J Vet Res. 1978;39(7):1089–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton BA, Schultz RD, Collins WE. Role of insects in the transmission of bovine leukosis virus: potential for transmission by mosquitoes. Am J Vet Res. 1982;43(8):1458–1459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiacomo RF, Hopkins SG, Darlington RL, Evermann JF. Control of bovine leukosis virus in a dairy herd by a change in dehorning. Can J Vet Res. 1987;51(4):542–544. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer JF, Piper CE. An evaluation of the role of milk in the natural transmission of BLV. Ann Rech Vet. 1978;9(4):803–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins SG, DiGiacomo RF. Natural transmission of bovine leukemia virus in dairy and beef cattle. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 1997;13(1):107–128. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0720(15)30367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono Y, Sentsui H, Arai K, Ishida H, Irishio W. Contact transmission of bovine leukemia virus under insect-free conditions. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi. 1983;45(6):799–802. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.45.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassauzet ML, Thurmond MC, Johnson WO, Stevens F, Picanso JP. Effect of brucellosis vaccination and dehorning on transmission of bovine leukemia virus in heifers on a California dairy. Can J Vet Res. 1990;54(1):184–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manet G, Guilbert X, Roux A, Vuillaume A, Parodi AL. Natural mode of horizontal transmission of bovine leukemia virus (BLV): the potential role of tabanids (Tabanus spp.) Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;22(3):255–263. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(89)90012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JM, van der Maaten MJ. Bovine leukosis--its importance to the dairy industry in the United States. J Dairy Sci. 1982;65(11):2194–2203. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(82)82482-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti GE, Frankena K, De Jong MC. Transmission of bovine leukaemia virus within dairy herds by simulation modelling. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(5):722–732. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuotio L, Rusanen H, Sihvonen L, Neuvonen E. Eradication of enzootic bovine leukosis from Finland. Prev Vet Med. 2003;59(1-2):43–49. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(03)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant JM, Lissemore KD, Martin SW, Leslie KE, McBride BW. Associations between winter herd management factors and milk protein yield in Ontario dairy herds. J Dairy Sci. 1997;80(11):2790–2802. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)76242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott HM, Sorensen O, Wu JT, Chow EY, Manninen K, VanLeeuwen JA. Seroprevalence of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis, Neospora caninum, Bovine leukemia virus, and Bovine viral diarrhea virus infection among dairy cattle and herds in Alberta and agroecological risk factors associated with seropositivity. Can Vet J. 2006;47(10):981–991. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher DJ, Pelzer KD, Lessard P. Possible effect of altered management practices on seroprevalence of bovine leukemia virus in heifers of a dairy herd with history of high prevalence of infection. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991;199(5):584–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurmond MC, Portier KM, Puhr DM, Burridge MJ. A prospective investigation of bovine leukemia virus infection in young dairy cattle, using survival methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117(5):621–631. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uysal A, Yilmaz H, Bilal T, Berriatua E, Bakirel U, Arslan M, Zerin M, Tan H. Seroprevalence of enzootic bovine leukosis in Trakya district (Marmara region) in Turkey. Prev Vet Med. 1998;37(1-4):121–128. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(98)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilesmith JW, Straub OC, Lorenz RJ. Some observations on the epidemiology of bovine leucosis virus infection in a large dairy herd. Res Vet Sci. 1980;28(1):10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blickenstorfer S, Engels M, Guerdat C, Saucy C, Reist M, Schwermer H, Perler L. [Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) in the canton of Jura: An epidemiological outbreak investigation] Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. pp. 555–560. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Christoph Riggenbach, "Eradication of IBR in Switzerland". http://www.bvet.admin.ch/gesundheit_tiere/01065/01083/01090/index.html?lang=de