Abstract

The unfolded protein response (UPR) is a signal transduction pathway that is activated by the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae the ER transmembrane receptor, Ire1p, transmits the signal to the nucleus culminating in the transcriptional activation of genes encoding an adaptive response. Yeast Ire1p requires both protein kinase and site-specific endoribonuclease (RNase) activities to signal the UPR. In mammalian cells, two homologs, Ire1α and Ire1β, are implicated in signaling the UPR. To elucidate the RNase requirement for mammalian Ire1 function, we have identified five amino acid residues within IRE1α that are essential for RNase activity but not kinase activity. These mutants were used to demonstrate that the RNase activity is required for UPR activation by IRE1α and IRE1β. In addition, the data support that IRE1 RNase is activated by dimerization-induced trans-autophosphorylation and requires a homodimer of catalytically functional RNase domains. Finally, the RNase activity of wild-type IRE1α down-regulates hIre1α mRNA expression by a novel mechanism involving cis-mediated IRE1α-dependent cleavage at three specific sites within the 5′ end of Ire1α mRNA.

Keywords: Endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mRNA degradation, mRNA splicing, unfolded protein response (UPR), signal transduction

The unfolded protein response (UPR) is a signaling pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the nucleus that protects all eukaryotic cells from stress caused by the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER (for review, see Chapman et al. 1998; Kaufman 1999; Pahl 1999). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Ire1p is an ER transmembrane protein with its amino terminus inside the ER lumen where unfolded or misfolded proteins accumulate under conditions of ER stress (Nikawa and Yamashita 1992; Cox et al. 1993; Mori et al. 1993). Its carboxyl terminus, composed of a Ser/Thr protein kinase domain and a site-specific endoribonuclease (RNase) domain, extends into the cytoplasm and/or the nucleoplasm (Mori et al. 1993; Sidrauski and Walter 1997). Ire1p senses unfolded proteins through an unknown mechanism and subsequent dimerization/oligomerization and autophosphorylation activates its dual catalytic activities that are required to initiate ER-stress-activated splicing of HAC1 mRNA (Shamu and Walter 1996; Welihinda and Kaufman 1996). Hac1p is a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor necessary for transcriptional activation of genes encoding ER protein chaperones and folding enzymes as well as ER protein degrading machineries (Cox and Walter 1996; Mori et al. 1996; Casagrande et al. 2000; Travers et al. 2000). Hac1p binds to a consensus UPR element (UPRE) in the promoter region of responsive genes. The level of Hac1p in the cell regulates transcriptional activity at the UPRE. HAC1 mRNA is constitutively expressed, but only a spliced form of HAC1 mRNA is translated efficiently. Splicing of HAC1 mRNA does not require the conventional eukaryotic mRNA splicesomal machinery. In contrast, the splicing reaction was reconstituted in vitro with only two components, Ire1p RNase and tRNA ligase Rlg1p (Sidrauski et al. 1996; Sidrauski and Walter 1997). Because the intron in unspliced HAC1u (uninduced) is a translation attenuator, only Hac1ip (induced) is completely synthesized and detected in the cell (Chapman and Walter 1997; Kawahara et al. 1997).

Although extensive evidence suggests that the UPR signaling pathway is conserved through evolution, the UPR in higher eukaryotic cells is more complex than that in yeast. Upon accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER, both adaptive and apoptotic signaling pathways are activated (Kaufman 1999). In higher eukaryotes, multiple mechanisms have been proposed to induce transcription of the ER stress-response genes, also known as genes encoding glucose-regulated proteins (GRPs), such as BIP (GRP78), GRP94, and ERP72 (Haas and Wabl 1983; Lee et al. 1984; Dorner et al. 1990; Muresan and Arvan 1997). Two related homologs of yeast IRE1, referred to as Ire1α and Ire1β, were identified in both the murine and human genomes (Tirasophon et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998; Niwa et al. 1999). Because the predicted products from the mammalian Ire1 genes, referred to as IRE1α and IRE1β, share the same domain structure as yeast Ire1p, it is possible that they signal the UPR through a similar mRNA splicing reaction. In support of this, the RNase specificity of hIRE1α and hIRE1β were conserved from yeast Ire1p, as evidenced by the ability of both enzymes to cleave at the 5′ and 3′ splice site junctions of yeast HAC1u mRNA (Tirasophon et al. 1998; Niwa et al. 1999). However, to date, a HAC1 homolog has not been identified in either the Caenorhabditis elegans or Drosophila melanogaster genomes or the genomes of other higher eukaryotes. In addition, nullizygous Ire1α mouse embryo fibroblasts display an intact UPR, supporting that additional pathways exist (Urano et al. 2000; W. Tirasophon and R.J. Kaufman, unpubl.). Finally, ATF6 is a 90-kD type II ER transmembrane protein that is cleaved on ER stress to generate a 50-kD cytoplasmic fragment that migrates to the nucleus to activate GRP gene transcription (Haze et al. 1999). Therefore, ER stress-induced proteolysis of ATF6 is one mechanism that can activate the UPR in higher eukaryotes. Because Atf6 mRNA is not detectably spliced on ER stress (Yoshida et al. 1998), there is question as to whether an IRE1-mediated HAC1 mRNA-like splicing reaction exists in higher eukaryotes.

Support for an IRE1-dependent pathway for UPR activation is based on the observation that overexpression of either IRE1α or IRE1β activated the UPR in transfected mammalian cells (Tirasophon et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998). However, it remains unknown whether the overexpressed IRE1 is recognized as an unfolded protein and activates the UPR indirectly, or whether IRE1 directly signals transcriptional activation of the GRPs. Amino acid substitution of the conserved lysine 599 for alanine within the hIRE1α kinase ATP-binding subdomain II destroyed kinase activity and reduced UPR signaling in transfected cells (Tirasophon et al. 1998). Interestingly, this single substitution also elevated hIre1α mRNA level and hIRE1α protein synthesis by approximately 15-fold. It was proposed that the kinase activity of hIRE1α autoregulates hIre1α mRNA expression (Tirasophon et al. 1998). This autoregulation appears important to limit hIRE1α expression because overexpression of either yeast IRE1 or mIre1β is toxic to cells (Shamu and Walter 1996; Wang et al. 1998). Through analysis of RNase-defective IRE1α and IRE1β single amino acid substitution mutants, we have elucidated the mechanism of this autoregulation. Using in vitro cleavage assays and functional analyses, we demonstrate that IRE1 is activated by trans-autophosphorylation-induced activation of the RNase function. The RNase activities of wild-type IRE1α and IRE1β were required for autoregulation of mRNA levels and for activation of the UPR.

Results

Site-directed mutagenesis identifies RNase-defective hIRE1α mutants

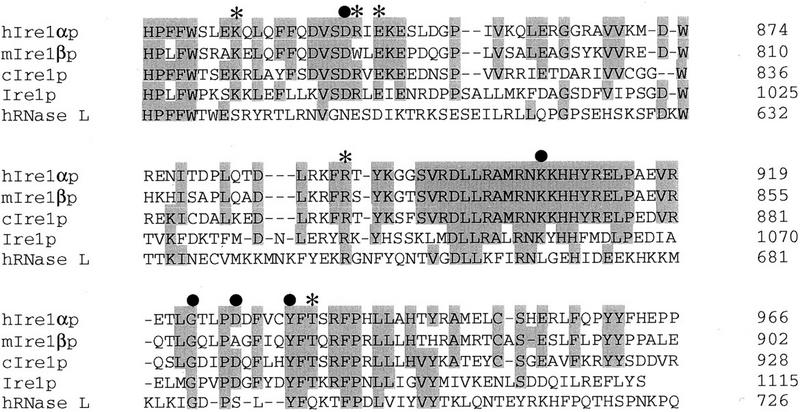

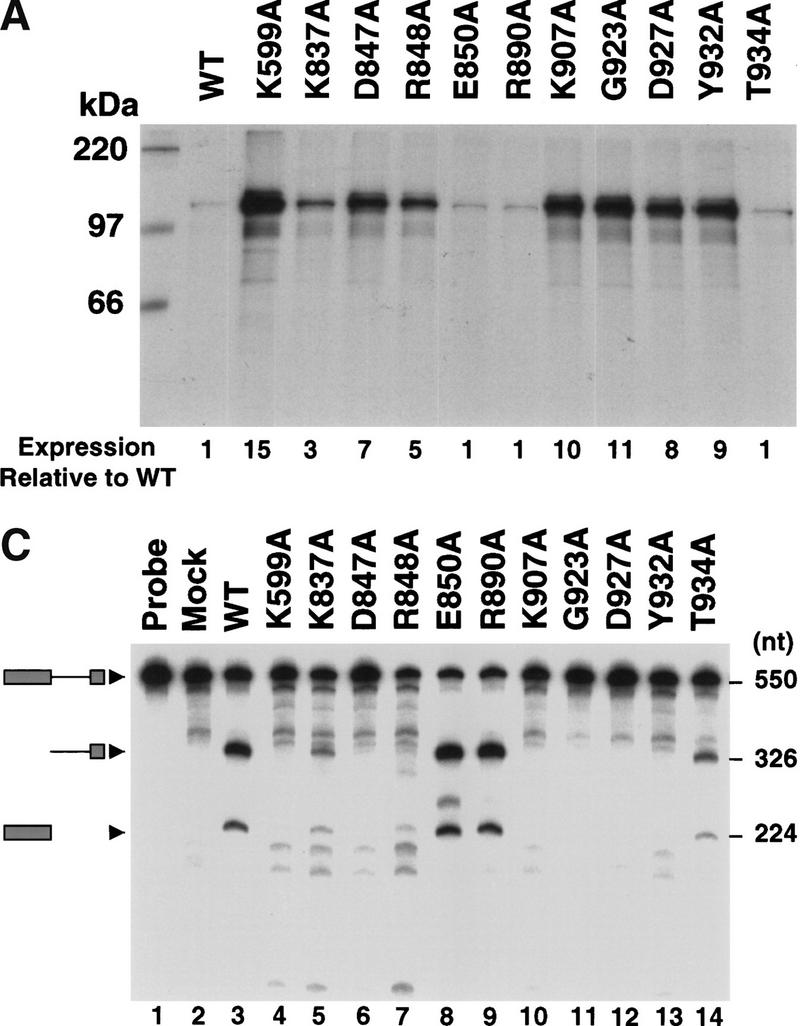

To elucidate the role for the RNase activity of hIRE1α in UPR signaling, a series of point mutants were made in conserved residues within the RNase domain. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the IRE1 RNase domains from four different species as well as human RNAse L, identified 20 invariant amino acid residues (Fig. 1). Ten mutant cDNAs were made in which Ala was substituted at positions Lys 837, Asp 847, Arg 848, Glu 850, Arg 890, Lys 907, Gly 923, Asp 927, Tyr 932, and Thr 934. The synthesis of the mutant hIRE1α proteins was measured by [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine pulse-labeling of transiently transfected COS-1 cells and immunoprecipitation of hIRE1α from prepared cell extracts (Fig. 2A). All the mutant proteins were expressed as polypeptides migrating with a molecular mass of ∼110 kD, although the expression level of individual mutant proteins varied dramatically. hIRE1α with Ala substitutions at residues Glu 850, Arg 890, or Thr 934 were synthesized at levels similar to wild-type (Fig. 2A). In contrast, Ala substitution at positions Lys 837, Asp 847, Arg 848, Lys 907, Gly 923, Asp 927, or Tyr 932 improved the expression level. Of these seven mutants, the D847A, K907A, G923A, D927A, and Y932A mutants were synthesized at levels close to the kinase-defective mutant hIRE1α (K599A) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the RNase domains of hIRE1α, mIRE1β, C. elegans IRE1, S. cerevisiae IRE1 and human RNase L. The conserved residues are shaded. Dashes represent gaps between residues to obtain maximal matching. Mutations that disrupt (filled circle) or do not effect (*) RNase activity are indicated. Numbers on the right are the position of the last amino acid.

Figure 2.

Expression and characterization of hIRE1α RNase domain mutants. (A) Expression of RNase domain mutants inversely correlates with RNase activity. COS-1 cells were transfected transiently with the expression plasmid encoding wild-type, kinase-defective (K599A), or mutant hIRE1α with the single amino acid substitutions indicated. Transfected cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine for 15 min. Cell extracts were prepared and equal numbers of counts were immunoprecipitated with anti-hIRE1α antibody and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The band intensities relative to the wild-type hIRE1α are indicated below. (B) Point mutations within the RNase domain of hIRE1α do not affect kinase activity. Wild-type and mutant hIRE1α proteins were immunoprecipitated from lysates of transfected COS-1cells with anti-hIRE1α antibody. The kinase activities in the immune complexes were determined by in vitro autophosphorylation in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a nylon membrane. The phosphorylation status was monitored by autoradiography (top). The amount of hIRE1α present in each lane was measured by Western blot analysis using mouse anti-hIRE1α antibody and rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (bottom). (C) Identification of five conserved amino acids required for hIRE1α RNase activity. An in vitro transcribed 32P-labeled HAC1 RNA fragment was incubated with immunoprecipitated wild-type or mutant hIRE1α protein. HAC1 RNA cleavage was monitored by denaturing gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Intact HAC1 RNA substrate and its cleaved products are shown on the left. Numbers on the right represent the predicted sizes of the RNA substrate and cleaved products.

Although these mutations reside outside the kinase domain, it is possible that the mutations may alter the overall structure of the protein and disrupt kinase function. Therefore, the protein kinase activity of these mutant hIRE1α proteins was measured by an in vitro autophosphorylation assay (Fig. 2B). The mutant hIRE1α molecules were immunoprecipitated from transfected COS-1 cells, incubated in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. All of these mutant proteins were efficiently autophosphorylated, supporting the hypothesis that they retain intact kinase activity (Fig. 2B, top). Importantly, the kinase-defective K599A mutant was not phosphorylated, indicating that contaminating cellular protein kinases were not responsible for the phosphorylation detected. Consistent with our previous observations (Tirasophon et al. 1998), phosphorylation of hIRE1α slightly reduced its mobility on SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis demonstrated the degree of phosphate incorporation into these mutants, except for K599A, roughly correlated with the steady state level of hIRE1α protein measured by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2B, bottom). Therefore, we conclude that the amino acid substitutions in the RNase domain do not significantly affect hIRE1α kinase activity.

To date, a natural RNA substrate for hIRE1α has not been identified. However, it was demonstrated previously that wild-type hIRE1α could efficiently cleave an in vitro transcribed yeast HAC1 RNA fragment at the correct 5′ splice site junction (Tirasophon et al. 1998). Cleavage of the 550 base HAC1 RNA fragment generated two RNA products: a 224-base fragment representing the 5′ exon and a 326-base RNA fragment representing the intron plus the 3′ exon (Fig. 2C, lane 3; Tirasophon et al. 1998). Under these conditions, cleavage at the 3′ splice site is inefficient and not detected (Tirasophon et al. 1998; Niwa et al. 1999). We utilized this assay to measure the RNase activity of the mutant hIRE1α proteins described above. RNase activity was observed for five hIRE1α mutants: K837A, R848A, E850A, R890A, and T934A that generated similarly sized cleavage fragments in variable amounts, indicating that these mutants are able to recognize and cleave the yeast HAC1 RNA substrate (Fig. 2C). The amount of yeast HAC1 RNA cleaved by E850A or R890A were comparable to those of the wild-type protein, indicating that their RNase activity was not altered (Fig. 2C, lanes 3,8,9). In contrast, RNase activity was not detected for mutants D847A, K907A, G923A, D927A and Y932A (Fig. 2C, lanes 6,10–13). Interestingly, the expression levels of the mutants inversely correlated with their RNase activity. For example, those mutants expressed at the highest level had undetectable RNase activity.

The RNase activity of wild-type hIRE1α down-regulates Ire1α mRNA

The inverse correlation between hIRE1α expression level and RNase activity suggested that the RNase activity of wild-type hIRE1α is required for hIre1α mRNA down-regulation. To test this hypothesis, Northern blot analysis was performed to measure the mRNA levels for each of the hIRE1α mutants. The expression level of the plasmid-derived hIre1α mRNA for each mutant in transfected COS-1 cells correlated well with its rate of protein synthesis (Figs. 2A, 3A). From these results, we conclude that the RNase activity of wild-type hIRE1α, and not its kinase activity, is essential to down-regulate hIre1α mRNA expression.

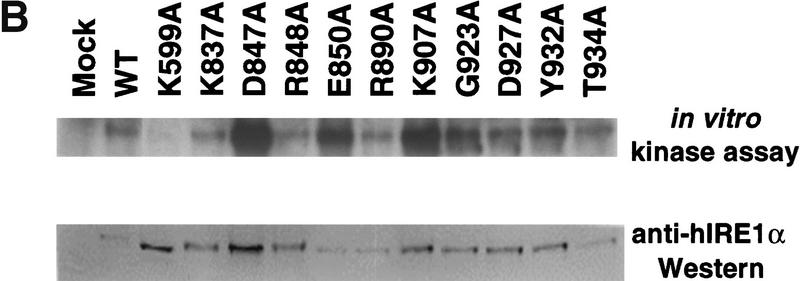

Figure 3.

RNase activity of hIRE1α reduces hIre1α mRNA levels. (A) Northern blot analysis of cells overexpressing mutant hIRE1α. Samples of total RNA obtained from COS-1 cells transfected with wild-type or mutant hIRE1α expression plasmids were resolved in a formaldehyde agarose gel. The hIre1α transcripts were probed with a 0.5 kb XbaI–BamHI fragment of hIre1α cDNA. The arrow identifies hIre1α mRNA. This autoradiogram is an overexposure in order to show the 5′ cleavage product of hIre1α mRNA (asterisk). (B) Identification of the 5′ end of hIre1α mRNA fragments by primer extension. Total RNA samples isolated from COS-1 cells transfected with wild-type (1 and 2) or K599A kinase-defective (3 and 4) hIRE1α expression plasmids were reverse transcribed using antisense hIre1α oligonucleotides in the presence of [α-35S]dATP. The same primers were used for DNA sequence analysis of the hIRE1α expression plasmid. Indicated residues are the positions where the reverse transcription ends. Lanes 1,3 and 2,4 are samples from two different transfection experiments. (C) Nucleotide sequences flanking the cleavage sites within hIre1 mRNA. Numbers on the right are the position of the last nucleotide relative to the initiation codon (the A in ATG is 1). Arrows indicate the predicted cleavage site within hIre1α mRNA. Underlined residues in HAC1 mRNA are resides that are conserved and required for cleavage by Ire1p (Kawahara et al. 1998; Gonzalez et al. 1999). (D) Cis- and trans-autoregulation of hIre1α mRNA expression. A T7-tagged kinase-defective full-length hIRE1α expression plasmid (top) or a truncated hIRE1α expression plasmid (bottom) was cotransfected with wild-type or mutant hIRE1α expression plasmids into COS-1 cells. Total RNA was prepared at 50 h posttransfection and analyzed by Northern blot hybridization. The blots were probed with an α-32P-labeled 3.5 kb EcoRI–XbaI fragment of hIre1α cDNA (top) or an α-32P-labeled 0.5 kb XbaI–BamHI fragment from the 5′ end of hIre1α cDNA (bottom). Arrows indicate positions of the plasmid-derived transcripts. hIre1α–T7 mRNA is smaller than hIre1α mRNA due to deletion of 3′ UTR during plasmid construction (see Materials and Methods). This autoradiogram is an overexposure to demonstrate the 5′ cleavage product of hIre1α mRNA (asterisk).

On overexposure of the Northern blot in Figure 3A, an extra RNA fragment (∼0.5 kb) that hybridized to the 5′-end of the hIre1α cDNA was detected in cells transfected with expression plasmids encoding the wild-type hIRE1α as well as the hIRE1α mutants K837A and R848A that exhibit RNase activity (Fig. 3A,D, bottom, asterisk). This fragment was not detected in RNA samples from mutants defective in RNase activity. Primer extension analysis was used to identify cleavage sites within the 5′ end of Ire1α mRNA. cDNA was synthesized using total RNA obtained from transfected COS-1 cells and antisense oligonucleotide primers specific to the hIre1α mRNA sequence. Four major primer-extended products were detected from wild-type hIre1α transfected cells (Fig. 3B). The 5′ end of these cDNAs ended at C187, G634, C663, and T664 of the hIre1α cDNA (where 1 is the A in the translation initiation codon) (Fig. 3C). The same primer-extended products were observed in cells transfected with the RNase-active hIre1α mutants (E850A and R890A, data not shown). However, these products were not observed from control untransfected cells or from cells transfected with the K599A kinase-defective hIre1α mutant (Fig. 3B; data not shown). These results support the conclusion that the truncated hIre1α mRNA species is either a direct or indirect product from the RNase activity of hIRE1α.

To further elucidate the mechanism of hIre1α mRNA autoregulation, we asked whether hIRE1α protein regulates hIre1α mRNA in cis or in trans. The wild-type, K599A kinase-defective, or the K907A RNase-defective mutant hIRE1α expression plasmids were cotransfected with a T7 epitope-tagged K599A kinase-defective hIRE1α expression plasmid (Fig. 3D, top). The expression vector encoding the T7-tagged hIRE1α has deleted the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) in hIre1α mRNA yielding a smaller sized mRNA that can be distinguished by Northern blot analysis. These expression vectors were also cotransfected with a carboxy-terminal-truncated hIRE1α expression plasmid to elucidate the requirement for RNA sequences in the 3′ half of hIre1α mRNA for autoregulation (hIRE1α ΔC, Fig. 3D, bottom). Overexpression of wild-type hIRE1α decreased the level of mRNA encoding T7-tagged kinase-defective hIRE1α-K599-T7 as well as hIRE1α ΔC. In contrast, overexpression of either K599A kinase mutant or K907A RNase mutant hIRE1α did not reduce the mRNA level derived from the cotransfected hIre1α (Fig. 3D, top, cf. lanes 2–4 with 7–9). Therefore, the RNase activity of hIRE1α was able to down-regulate the mRNAs encoding either T7-tagged kinase-defective hIRE1α or the hIREα ΔC mutant in trans. Because hIre1α ΔC mRNA was also reduced by the RNase activity of hIRE1α, sequences 3′ to nucleotide 1634 are not required for down-regulation (Fig. 3D, bottom). Interestingly, quantification of the amount of mRNA reduced in trans (1.7-fold for hIre1α-K599A-T7) compared to the amount reduced in cis (3.6-fold for the hIre1α), indicated that the majority of hIre1α mRNA was degraded in cis.

We then asked whether hIRE1α could cleave its own mRNA in vitro. An assay similar to the yeast HAC1 mRNA cleavage reaction shown in Figure 2C was performed using an in vitro-transcribed 32P-labeled truncated 800-bp fragment from the 5′ end of hIre1α mRNA as a substrate. Specifically cleaved hIre1α mRNA products were not detected under conditions where control yeast HAC1 mRNA was cleaved by hIRE1α (data not shown). It is possible that the cleavage of hIre1α mRNA by hIRE1α in vitro may be very inefficient, may require additional cellular factors, or may require an mRNA engaged with ribosomes. Taken together, the results demonstrate the RNase activity of wild-type hIRE1α is required to down-regulate hIre1α mRNA and that hIRE1α may act in cis as well as in trans to initiate hIre1α mRNA cleavage.

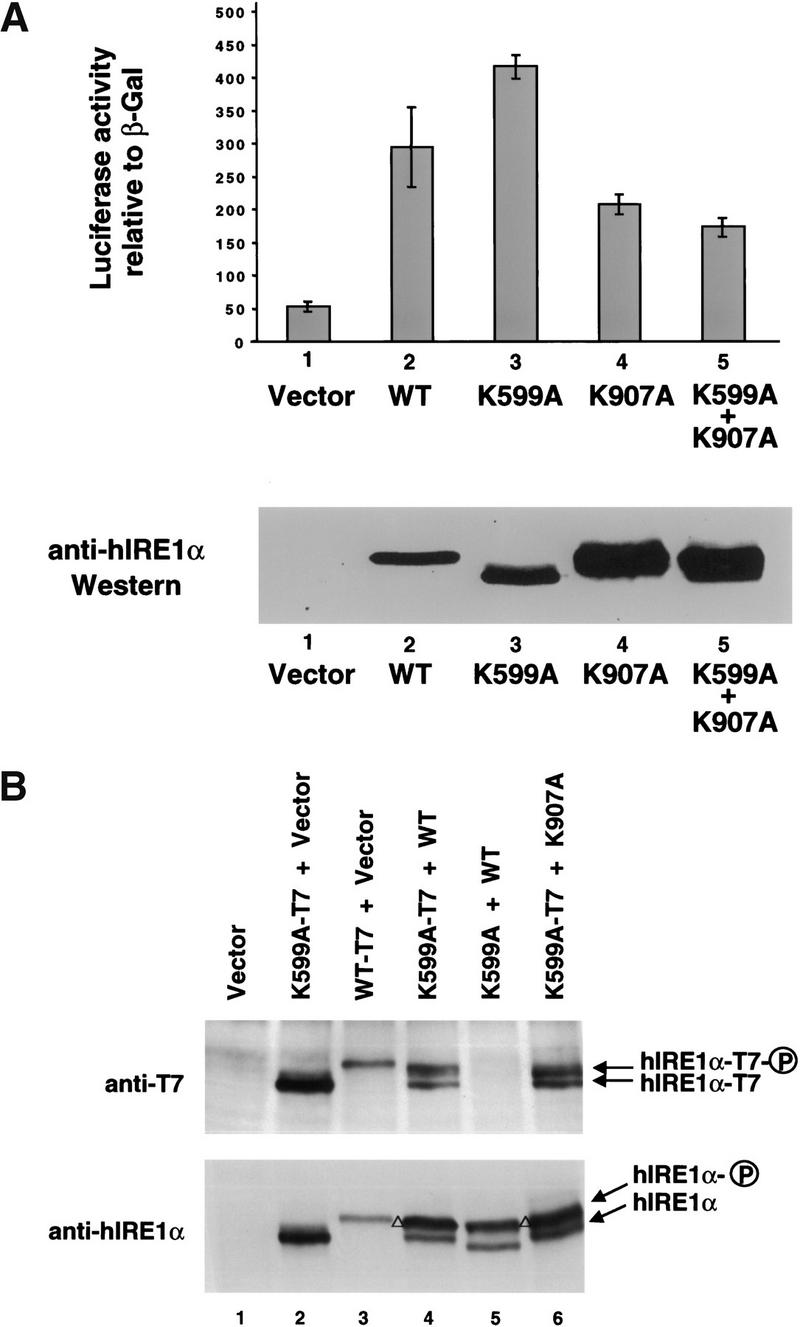

The RNase activity of hIRE1α is required for UPR signaling

The conserved specificity between yeast Ire1p and hIRE1α for cleaving the 5′ and 3′ splice sites of yeast HAC1 mRNA suggests the possibility that a splicing reaction similar to that characterized in yeast is conserved in higher eukaryotic cells. However, a mammalian RNA substrate equivalent to yeast HAC1 mRNA has not been identified. To test directly whether the RNase activity of hIRE1α is essential for activation of the mammalian UPR, a luciferase reporter plasmid under control of the rat BIP promoter was cotransfected with wild-type or mutant hIRE1α expression plasmids into COS-1 cells. To correct for transfection efficiency, cells were cotransfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector. The luciferase activity relative to β-galactosidase activity detected in the cell extract reflects the hIRE1α-mediated trans-activation of the rat BIP promoter. On tunicamycin treatment to promote accumulation of unglycosylated and misfolded protein in the ER, control cells transfected with empty vector activated the rat BIP promoter approximately fourfold (Fig. 4A). Overexpression of wild-type hIRE1α or the RNase-active mutants (E850A and R890A) activated the BIP promoter in the absence of tunicamycin treatment, and tunicamycin treatment did not significantly increase BIP reporter gene expression any further (Fig. 4A). In contrast, overexpression of the RNase-defective hIRE1α mutants ΔC, K907A or G923A did not induce luciferase reporter gene expression in the absence of tunicamycin, and actually reduced the tunicamycin-dependent activation of this reporter (Fig. 4A). We consistently observed that the hIRE1α ΔC mutant acts as a stronger dominant negative than the RNase-defective hIRE1α mutants. Previous experiments suggested that the kinase-defective K599A mutant hIRE1α might also act in a trans-dominant negative manner to inhibit endogenous hIRE1α (Tirasophon et al. 1998). However, more detailed analysis has shown that this mutant hIRE1α does activate the BIP reporter construct compared to the vector, although to a variable extent (Fig. 4A). The variable activation of the BIP reporter by the K599A mutant may depend on the growth conditions of the cell that may influence the activation status of endogenous IRE1. These results show that the RNase activity of hIRE1α is required to activate the UPR. In addition, the RNase-defective hIRE1α mutants act in a trans-dominant negative manner to inhibit the endogenous UPR signaling pathway activated by accumulation of unfolded unglycosylated proteins in the ER, although less effectively than truncated hIRE1α ΔC.

Figure 4.

The RNase activity of hIRE1α is required for the mammalian UPR. (A) The reporter plasmids containing the luciferase gene under control of the rat BIP promoter and β-galactosidase under control of the SV40 early promoter were cotransfected with the hIRE1α expression plasmids into COS-1 cells as indicated. The transfected cells were treated with 10 μg/ml tunicamycin for 6 h prior to harvest. The luciferase activities are presented relative to SV40 β-galactosidase activities. Similar results were obtained from two independent experiments. (B) Cells were transfected as above in the presence of pMT2-μ or pMT2-Δsμ. The vector used for wild-type and mutant hIRE1α expression is pEDΔC.

To test whether overexpression of a wild-type glycosylated protein can also activate hIRE1α, ER stress was induced by overexpression of immunoglobulin μ heavy chain in the absence of its light chain. Expression of μ heavy chain activated the BIP reporter in cotransfection experiments. Compared to overexpression of the wild-type hIRE1α, overexpression of K599A kinase mutant displayed intermediate activation and expression of the K907A RNase mutant blocked activation by μ immunoglobulin overexpression (Fig. 4B; μ). In contrast, overexpression of a mutant μ heavy chain deleted of the signal peptide (Srinivasan et al. 1993), so that it is not translocated into the ER lumen, did not activate the BIP reporter construct (Fig. 4B; Δsμ). This result shows that overexpression of the RNase-defective hIRE1α can prevent activation of the UPR on wild-type protein translocation into the ER lumen. This is the first data supporting that overexpression of a secreted wild-type protein can signal through hIRE1α to activate the UPR. From these results we conclude that the RNase activity is essential for hIRE1α to activate the mammalian UPR.

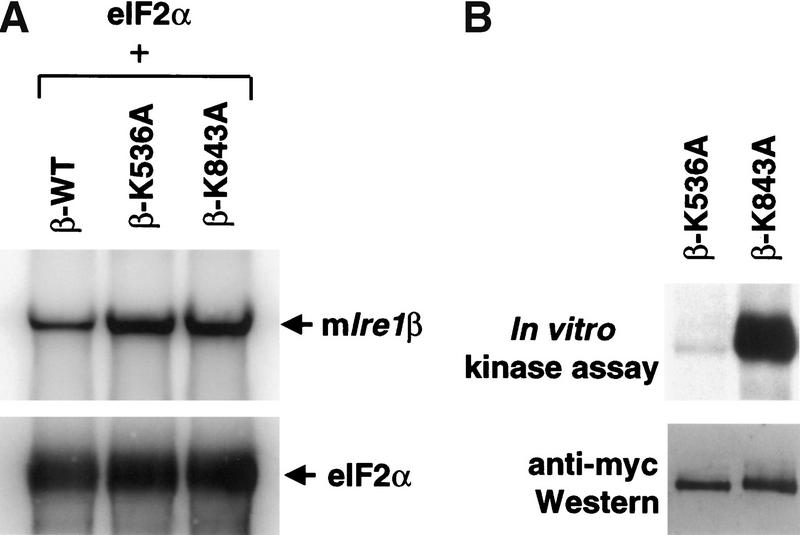

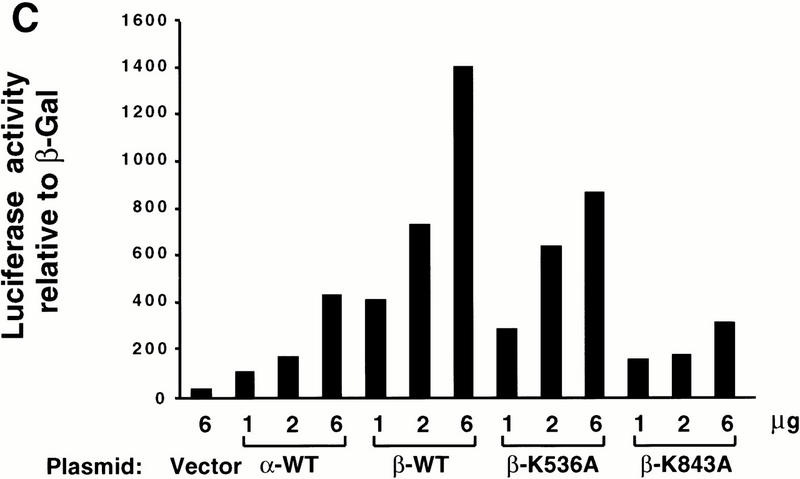

The RNase activity of mIRE1β is required for autoregulation and signaling

Two mammalian Ire1 homologs, Ire1α and Ire1β, exist which are each able to activate the UPR on overexpression in mammalian cells (Tirasophon et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998; Niwa et al. 1999). Their conservation in domain structure and amino acid sequence suggests that IRE1β may share a number of properties with IRE1α. To study the role of the RNase activity in IRE1β, we introduced a K843A mutation into IRE1β, the residue homologous to Lys 907 that is required for RNase activity in hIRE1α. The mRNA levels for wild-type, the kinase-defective (K536A), and the RNase-defective (K843A) mIRE1β mutants were measured after transient transfection into COS-1 cells. Expression vectors were cotransfected with a vector encoding eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) as an internal transfection control (Tirasophon et al. 1998). Compared with the kinase-defective and RNase-defective mutants, the expression level of wild-type mIre1β mRNA was reduced threefold where there was no reduction in the mRNA encoding eIF2α (Fig. 5A). These results support that the RNase activity of wild-type mIRE1β specifically degrades mIre1β mRNA. Whereas wild-type mIRE1β was not detected on Western blot analysis (data not shown), both the K536A kinase mutant and the K843A RNase mutant were detected readily (Fig. 5B). Immunoprecipitation and in vitro kinase activity assay demonstrated that the RNase-defective K843A mutant mIRE1β was autophosphorylated (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the mutation in the RNase domain of mIRE1β did not interfere significantly with kinase activity.

Figure 5.

The RNase activity of mIRE1β is required for mRNA autoregulation and activation of the UPR. (A) Northern blot analysis of mIre1β mRNA. COS-1 cells were transfected with a plasmid carrying eIF2α and either wild-type, kinase-defective (K536A), or RNase defective (K843A) mIRE1β expression plasmids as indicated. Total RNAs were prepared at 40 h posttransfection and analyzed by Northern blot hybridization. The blots were probed with α-32P-labeled 3.0 kb EcoRI–XhoI fragment of pcDNA-mIre1β–myc (top) and a 0.25 kb exon 2 fragment of eIF2α (bottom). The vector used for wild-type and mutant mIRE1β expression is pcDNA3 and eIF2α is expressed in pED. Arrows indicate the positions of plasmid-derived transcripts. (B) In vitro kinase assay of mIRE1β. COS-1 cells were transfected with either kinase-defective mIRE1β or RNase-defective mIRE1β expression plasmids. Cell lysates were prepared at 40 h posttransfection, immunoprecipitated, and subjected to in vitro kinase assay as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were separated in a 6% acrylamide gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane before quantitation by PhosphorImaging (top). The same blot was analyzed by Western blot analysis using anti-c-Myc epitope antibody and anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Band intensities were measured after enhanced chemilumenescence (bottom). (C) The RNase activity of mIRE1β is required to activate the UPR. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with BIP-luciferase reporter, the SV40–β-gal reporter, and the indicated mutants of mIRE1β. Analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

We then tested whether the RNase activity of mIRE1β is required to activate the BIP reporter gene. Transfection of increasing amounts of mIre1β activated BIP reporter gene expression significantly greater than that observed for hIre1α (Fig. 5C). Although we could not compare directly the expression levels of hIRE1α and mIRE1β, Western blot analysis suggests that mIRE1β is expressed at a lower level than hIRE1α (Figs. 5B,6; and data not shown). Transfection of the K536A kinase mutant mIre1β displayed an intermediate activation, whereas transfection of the K843A RNase mutant mIre1β did not activate the BIP reporter gene (Fig. 5C). Cotransfection of wild-type mIre1β with wild-type hIre1α did not yield greater activation of the BIP reporter than that observed with mIre1β alone (data not shown). In addition, the hIRE1α RNase mutant did not reduce activation provided by wild-type mIRE1β and vice versa, indicating that the products from these two homologous genes did not interact, an observation also supported by coimmunoprecipitation (data not shown). Finally, the pattern of BIP promoter activation shown in Figure 5C was identical to that observed when using an ERP72 promoter linked to chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) as reporter (Srinivasan et al. 1993; data not shown). Although these studies support that these two different UPR-inducible genes are activated by hIRE1α or mIRE1β overexpression, mIRE1β is a more potent activator than hIRE1α for both the BIP and ERP72 promoters. In conclusion, these results demonstrate that both IRE1α and IRE1β require the RNase activity to signal transcriptional activation.

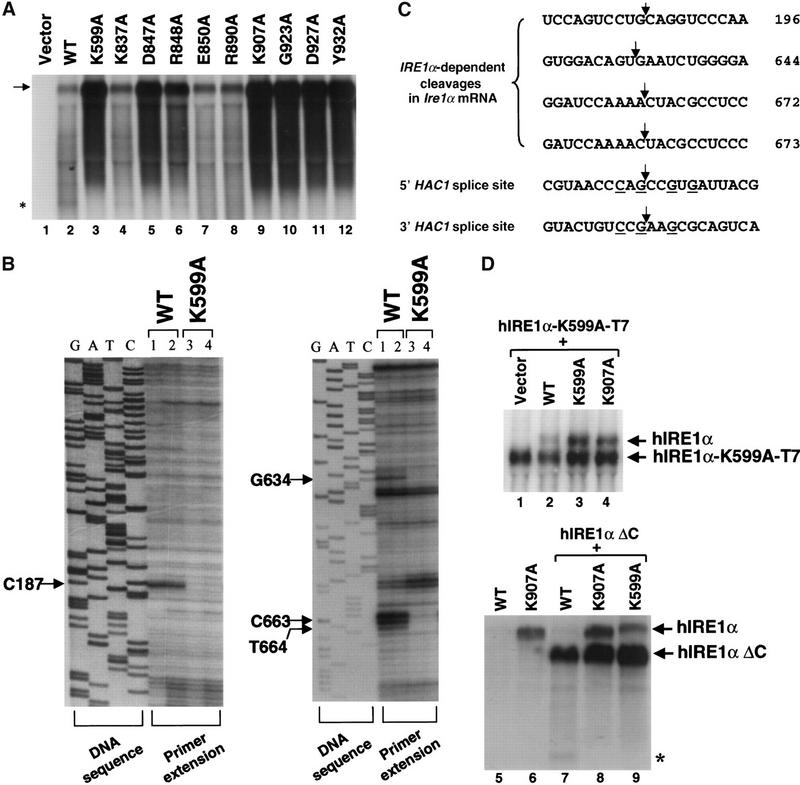

Figure 6.

Two functional RNase domains are required for the RNase activity of hIRE1α. (A) RNase-defective and kinase-defective IRE1α mutants do not trans-complement each other. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with the ERP72 CAT reporter construct and the indicated mutants of hIRE1α. Cell lysates were prepared and CAT protein and β-galactosidase activity were measured as described in Materials and Methods. The error bars represent the average of two independent experiments. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-hIRE1α antibody that reacts with the luminal domain of hIRE1α (bottom). (B) hIRE1α is autophosphorylated by both inter- and intramolecular phosphorylation reactions. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with pEDΔC vector, or vector expressing wild-type, kinase-defective (K599A), or RNase-defective (K907A) hIRE1α as indicated. In the cotransfection experiments, equal amounts of each plasmid DNA were used. Protein extracts were prepared at 48 h posttransfection and were subjected to Western blot analysis using mouse anti-T7 antibody (top) or mouse anti-hIRE1α luminal domain antibody (bottom). Detection was performed with rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase using enhanced chemilumenescence. The arrows indicate the migration of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated hIRE1α. The open triangle on the left side of the lane indicates migration of a phosphorylated doublet of full-length and T7-epitope tagged hIRE1α. The T7-epitope tagged IRE1α molecules migrate slightly slower than untagged IRE1α molecules.

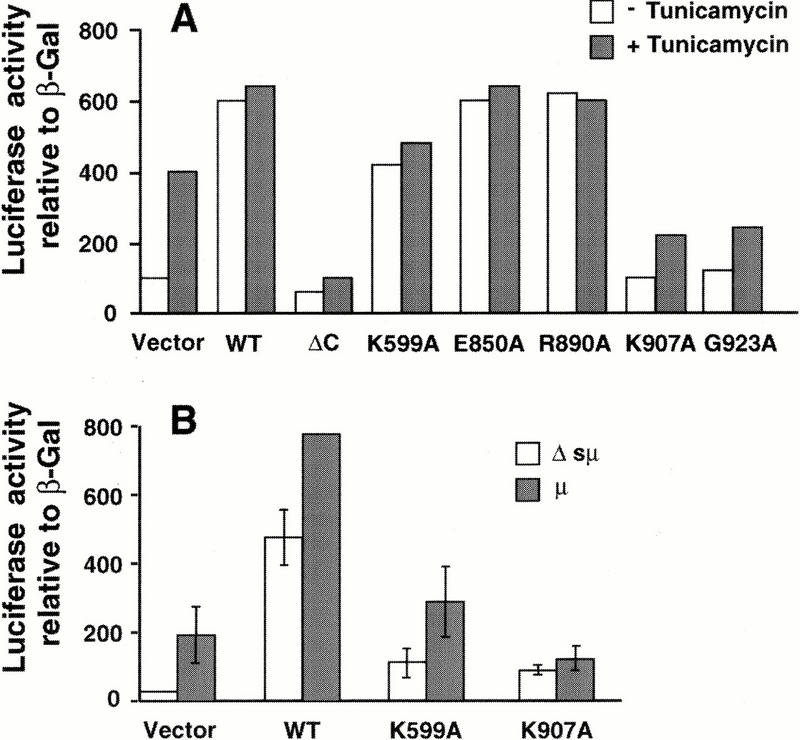

The IRE1α mutant in RNase activity cannot complement in trans an IRE1α mutant in kinase activity

Because the RNase-defective hIRE1α mutants act in a trans-dominant negative manner to inhibit the endogenous UPR signaling pathway, we propose that the mutant protein dimerizes with endogenous IRE1 to prevent signaling. If dimerization occurs, then we may expect that the kinase activity of the K907A RNase-defective hIRE1α should complement the K599A kinase-defective hIRE1α. This hypothesis was tested by coexpression of the kinase-defective (K599A) and RNase-defective (K907A) hIRE1α molecules to measure activation of the ERP72 promoter using the ERP72-CAT construct (ERPTRE-CAT; Srinivasan et al. 1993). Surprisingly, the induction caused by overexpression of K599A kinase-defective IRE1α was blocked by coexpression of the K907A RNase-defective hIRE1α mutant (Fig. 6A). The CAT expression in cells cotransfected with the RNase-defective hIRE1α and the kinase-defective hIRE1α was as low as that measured in cells transfected with the RNase-defective hIRE1α alone and lower than that in cells transfected with the kinase-defective hIRE1α alone (Fig. 6A). Western blot analysis demonstrated that each of the coexpressed proteins was expressed well (Fig. 6A, bottom). Similar results were obtained during analysis of the BIP reporter gene (data not shown), demonstrating that the RNase-defective hIRE1 can function in a trans-dominant negative manner to prevent UPR transcriptional activation at both the BIP and ERP72 promoters. These findings support that hIRE1α forms a homodimer and two functional RNase domains are required to activate the UPR.

To examine whether trans-phosphorylation between hIRE1α molecules occurs, Western blot analysis was performed on lysates from transfected COS-1 cells. By Western blot analysis, it is possible to distinguish unphosphorylated hIRE1α from phosphorylated hIRE1α due to the slower migration of the latter on reducing SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with anti-T7 and anti-hIRE1α antibodies. Cells transfected with T7-tagged kinase-defective K599A mutant hIRE1α displayed a single species that was detected by both antibodies (Fig. 6B, lane 2). In contrast, cells transfected with T7-tagged wild-type hIRE1α had a slower migrating species, corresponding to phosphorylated hIRE1α, that also reacted with both antibodies (Fig. 6B, lane 3). Cells cotransfected with wild-type hIRE1α and the T7-tagged K599A mutant hIRE1α displayed two species corresponding to phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated hIRE1α that were detected with the anti-hIRE1α antibody. However, the anti-T7 antibody also detected phosphorylated forms of the T7-tagged K599A mutant hIRE1α (Fig. 6B, lane 4), demonstrating that phosphorylation of this molecule is dependent on the wild-type hIRE1α. For an antibody control, no species were detected with the anti-T7 antibody in the absence of the T7-epitope tag on wild-type and K599A mutant hIRE1α molecules (Fig. 6B, lane 5). Finally, the K599A mutant hIRE1α was also phosphorylated by the K907A RNase-defective hIRE1α (Fig. 6B, lane 6). Importantly, the level of phosphorylated hIRE1α in these cotransfected cells was significantly greater than that observed for the wild-type hIRE1α transfected cells (Fig. 6B, cf. lane 3 with 6), although there was no activation of the reporter gene (Fig. 6A). These results demonstrate that trans-autophosphorylation between mutant hIRE1α molecules can occur. However, although the RNase-defective hIRE1α was able to phosphorylate the kinase-defective hIRE1α mutant, this phosphorylation was not sufficient to activate the RNase activity of the kinase mutant.

Discussion

IRE1 is structurally related to type I growth factor receptors that require dimerization and/or oligomerization for activation (Lemmon and Schlessinger 1994; Wrana et al. 1994; Heldin 1995). Therefore, the concentration of these receptors is regulated tightly at a level that prevents spontaneous dimerization and activation, and at the same time permits rapid signaling on demand. The requirement for stringent Ire1 expression is underscored by the observation that overexpression of mammalian hIRE1β induces apoptosis (Wang et al. 1998). Previous studies in transfected COS-1 cells demonstrated that expression of wild-type hIRE1α protein and mRNA is ∼15-fold lower compared to kinase-defective (K599A) mutant hIRE1α (Tirasophon et al. 1998), suggesting that hIRE1α may negatively autoregulate its expression. To test this hypothesis, we have introduced specific point mutations into conserved residues in the RNase domain of hIRE1α to study its functional significance.

The novel RNase domain of hIRE1α has homology to RNase L, a 741 amino acid protein that mediates the interferon antiviral response (Diaz-Guerra et al. 1997; Stark et al. 1998). Despite structural similarities, the two proteins are involved in different cellular processes. Whereas RNase L is a nonspecific RNase that participates in degradation of cellular RNAs on viral infection, yeast Ire1p requires cleavage specificity to mediate the UPR. RNase L is activated by binding of 2′,5′-linked oligoadenylates (2′,5′-A). Upon binding to 2′,5′-A molecules, the inactive monomeric form of RNase L dimerizes into its catalytically active form that can bind substrate (Dong and Silverman 1995; Cole et al. 1997). Although RNase L was cloned in 1993, very little is known regarding its structural requirements for RNase activity. Dong and Silverman (1997) demonstrated that residues 710–720 are required for substrate binding and catalytic activity. Interestingly, these residues are outside the region (residues 587–706) that has homology to IRE1 (Fig. 1). Most of the mutations we made were at residues conserved between IRE1 molecules from human, C. elegans, and S. cerevisiae. To identify potential determinants in RNA cleavage specificity for hIRE1α, mutations were constructed at two residues that were not conserved in mIRE1β and at seven residues that were not conserved in RNase L. Our mutagenesis studies demonstrated that hIRE1α residues G923 and Y932 are required for hIRE1 RNase activity. Because these residues are conserved in RNase L, they may be essential for catalytic function. Residues D847, K907, D927, and T934 were required for IRE1α RNase activity toward yeast HAC1 RNA and are not conserved in RNase L. Interestingly, three of these residues alter charge between IRE1α and RNase L, possibly suggesting substrate interaction sites. Finally, the homologous residue for D927 in hIRE1α is Ala in mIRE1β. However, the D927A hIRE1α mutant did not display RNase activity. Because all known Ire1 genes encode acidic amino acid residues in this position, the Ala in mIRE1β may be a cloning error. We have confirmed that the mIre1β DNA sequence isolated previously (Wang et al. 1998) does encode an Ala at this position. Future studies will characterize the interaction of IRE1α and IRE1β with their RNA substrates, once they are identified. Significantly, our studies are the first to separate the kinase activity from the RNase activity in IRE1.

Although autophosphorylation of hIRE1α has been reported (Tirasophon et al. 1998), we have now demonstrated that trans-autophosphorylation between hIRE1α molecules occurs. However, the UPR-signaling activity of the K599A kinase-defective hIRE1α was not activated by the kinase activity of the K907A RNase-defective hIRE1α mutant. Although there are several interpretations for this observation, we propose that functional RNase activity requires a homodimer of functional RNase domains where each RNase domain contributes a necessary function for catalytic activity. This is somewhat analogous to tRNA endoribonuclease where the active enzyme requires a homodimer of two functional RNase molecules (Trotta et al. 1997). We propose that ER stress promotes dimerization of the inactive IRE1 monomers and subsequent trans-autophosphorylation. Recent studies are consistent with dimerization-induced activation of IRE1α on ER stress (Bertolotti et al. 2000; Liu et al. 2000). Phosphorylation of the molecule then induces a conformational change to activate the RNase function. The RNase function requires that IRE1 be maintained as a dimer. The RNase activity may be attenuated by action of a phosphatase or by dissociation of the homodimer. The studies support that it may be possible to limit activation of IRE1 by design of molecules that prevent dimerization. Future studies are required to identify sites of phosphorylation and their role in the activation of the RNase activity.

The mRNAs encoding RNase-defective hIRE1α molecules that retain kinase function were all expressed at ∼15× greater levels than the wild-type or RNase active mutants, demonstrating that the RNase activity, and not the kinase activity, of hIRE1α is required for hIre1α mRNA down-regulation. The most direct interpretation of these results is that the RNase activity of hIRE1α initiates degradation of hIre1α mRNA. However, our in vitro studies did not detect direct cleavage of hIre1α mRNA by hIRE1α protein. Surprisingly, hIRE1α protein preferentially degraded hIre1α mRNA in cis compared to in trans. The preferential cis-dependent autoregulation suggests that hIRE1α-mediated decay of hIre1α mRNA is independent of hIRE1α concentration and therefore is likely not a consequence of hIRE1α overexpression. The observation that degradation occurs in cis suggests that cleavage may be initiated while the nascent polypeptide is still associated with the polysome. We propose that the amino-terminal end of the cytosolic domain within the nascent IRE1 polypeptide binds to the 5′ end of its own mRNA. After release of the nascent chain from the ribosome, IRE1 dimerizes to activate the RNase activity to initiate Ire1 mRNA degradation. The RNase-dependent autoregulation of hIre1α mRNA was not unique because similar findings were made in analysis of hIre1β mRNA expression, although regulation was to a lesser degree. These findings have elucidated a unique strategy for gene regulation in which a protein utilizes its RNase activity to fine-tune its mRNA expression.

A partially degraded 0.5-kb mRNA fragment derived from the 5′ end of hIre1α mRNA was identified in cells overexpressing the wild-type or the RNase active mutants of hIRE1α, but was absent in cells overexpressing RNase-defective hIRE1α. To our knowledge, this is the first in vivo identification of a cleavage intermediate in an mRNA degradation pathway in higher eukaryotes. Primer extension analysis identified several cleavage sites, although alignment of the nucleotide sequences flanking these sites with that of the 5′ and 3′ splice sites of yeast HAC1 mRNA did not identify any conserved features (Fig. 3C). These cleavage sites do not possess a stem structure with a seven-member nucleotide ring that was proposed to be crucial for substrate recognition by yeast Ire1p (Sidrauski and Walter 1997; Kawahara et al. 1998). They also do not display the 3–4 conserved residues found to be required for HAC1 mRNA cleavage (Fig. 3C) (Kawahara et al. 1998; Gonzalez et al. 1999). It is possible that hIRE1α cleaves hIre1α mRNA in association with another factor(s) that lessens its sequence specificity in vivo. Alternatively, the RNase activity of hIRE1α may activate a second RNase that displays a lesser sequence specificity and cleaves hIre1α mRNA. In this context, it is interesting to note that one of the cleavage sites we identified is after CUG, which fits the consensus site for cleavage detected by the Xenopus laevis estrogen-regulated polysomal nuclease involved in degradation of albumin mRNA (Chernokalskaya et al. 1997). This CUG cleavage specificity was also characterized for a polysomal-associated RNase that degrades the c-Myc mRNA (Lee et al. 1998). With this in mind, it is possible that the hIRE1α RNase activity may contribute to the degradation of c-Myc and albumin mRNAs.

Overexpression of hIRE1α or hIRE1β activates the UPR in mammalian cells (Tirasophon et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998). However, it is unknown whether mammalian cells have a yeast-like IRE1-mediated HAC1 mRNA splicing reaction. To date, a bZIP homolog of S. cerevisiae HAC1 has not been identified in higher eukaryotes, including the sequenced C. elegans and D. melanogaster genomes. Although Niwa et al. (1999) have reported that yeast HAC1 mRNA can be spliced in mammalian cells, we have not observed this in our laboratory (Foti et al. 1999). In addition, it is not necessary to invoke RNase activity for UPR signaling because Mori and co-workers demonstrated that overexpression of the bZIP transcription factor ATF6 can activate transcription from the ER stress response element (ERSE) (Haze et al. 1999). The activity of ATF6 is regulated by ER-stress-induced proteolysis to generate a DNA-binding and transcription-activating fragment of ATF6 (a 50-kD protein) that translocates to the nucleus. In addition, Atf6 mRNA processing was not detected on ER stress (Yoshida et al. 1998). Finally, deletion of mIre1α in mouse embryonic fibroblasts did not reduce the induction of BIP on ER stress (Urano et al. 2000; W. Tirasophon et al., unpubl.). However, our results show that overexpression of hIRE1α or mIRE1β activated the UPR in a manner that required the RNase activity, supporting that a HAC1 mRNA-like splicing reaction exists in mammalian cells and that hIRE1α and mIRE1β share a common substrate. This common substrate signals to activate both the BIP and ERP72 promoters. It is possible that IRE1-mediated splicing may activate the translation of a protease that subsequently cleaves ATF6 (Yoshida et al. 1998). In support of this hypothesis, Wang et al. (2000) demonstrated recently that the kinase-defective hIRE1α mutant K599A blocks ER stress-induced activation of ATF6 in mammalian cells, suggesting that ATF6 cleavage is downstream from IRE1α signaling.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction and site-directed mutagenesis

To create RNase mutant hIRE1α clones, a 3-kb XbaI–EcoRI fragment from pED-hIRE1α was subcloned into the pALTER plasmid (Promega). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed according to the manufacturer's procedure. Ten mutant cDNAs were created using the following primers: K837A, 5′-ACTGGA GCTGCGCCTCTAGGCTCC-3′; D847A, 5′-TTTCTATTCTG GCGCTCACGTCC-3′; R848A, 5′-CCTTTTCTATTGCGTC GCTCACGT-3′; E850A, 5′-GGGATTCCTTTGCTATTCTGT CG-3′; R890A, 5′-CTTTATAGGTCGCGAATTTACGCA-3′; K907A, 5′-AGTGGTGCTTCGCATTTCTCATGG-3′; G923A, 5′-CGGGGAGGGTCGCCAGCGTCTCC-3′; D927A, 5′-AC GCCGTCGGCGGGGAGGGTC-3′; Y932A, 5′-GAGACGTGA AGGCGCACACGCCGT-3′; T934A, 5′-GAAGCGAGACGCG AAGTAGCACA-3′.

Mutated residues are represented in bold, and mutated triplet codons are underlined. Two independent clones from each mutagenesis reaction were subcloned into the pEDΔC mammalian expression plasmid (Kaufman et al. 1991) and characterized. Wild-type and K599A hIre1α cDNAs with a T7 epitope tag were created by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the oligonucleotide primer 5′-CCGCTCGAGTTAACCCATTTGCT GTCCACCAGTCATGCTAGCCATTCCGAGGGCGTCTGG AGTCAC-3′. To construct HA-tagged hIRE1α ΔC, a 0.2-kb fragment corresponding to nucleotides 1455–1634 of hIre1α was amplified by PCR using primers 5′-GCTGATTGGCTGGGTG GCCTTC-3′ and 5′-CCGGAATTCAAGCGTAGTCTGGGAC GTCGTATGGGTAGCTGTCCAGGAGCTCGCCG-3′ and Vent DNA polymerase. The PCR fragment was digested with NsiI and EcoRI and then subcloned into the respective sites in pED–hIRE1α. Wild-type and K536A mutant mIRE1β cDNAs cloned into pcDNA3 were a gift from Dr. David Ron (New York University Medical School, New York). The RNase-defective mIRE1β (K843A) was created by site-directed PCR mutagenesis using the following primers: K843A-1, 5′-CCCTGTAGTGGT GCTTCGCGTTCCTCATGGC-3′ K843A-2, 5′-GCCATGAG GAACGCGAAGCACCACTACAGGG-3′ 5820G, 5′-CCTCG GCAGGATGGGTACTGGCTC-3′ 5823G-myc, 5′-GGGGCT CGAGTCACAGATCCTCCTC-3′. Mutated residues are represented in bold, and mutant triplet codons are underlined. All mutations were verified by DNA sequencing.

The immunoglobulin μ expression vectors and the ERPTRE-CAT reporter were described previously (Srinivasan et al. 1993) and kindly provided by Dr. Michael Green (St. Louis University, St. Louis, MO). The eIF2α expression vector pED-2α (Kaufman et al. 1991) and the BIP-luciferase reporter plasmid (Tirasophon et al. 1998) were described previously.

Transient DNA transfection and analysis in mammalian cells

COS-1 monkey cells were cultured and DNA transfection was performed and analyzed as described previously (Tirasophon et al. 1998). At 60 h posttransfection the transfected cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine (>1000 Ci/mmole, Amersham Pharmacia) for 15 min prior to harvesting the cells.

Immunoprecipitation analysis

Cell extracts were preadsorbed with protein A sepharose. The precleared lysates were subsequently incubated with anti-hIRE1α, anti-c-Myc epitope or anti-T7 epitope antibodies in NP-40 lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors at 4°C for 14 h and then incubated with rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody for 1 h. The immune complexes were adsorbed to protein A sepharose and washed sequentially with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing Triton X-100 at 1%, 0.1%, and 0.05%.

In vitro phosphorylation and Western blot analysis

Immunoprecipitated hIRE1α or mIRE1β from transfected COS-1 cells was incubated in kinase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na2MoO4) containing 2 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 10 μCi [γ-32P]ATP (6000 Ci/mmole, Amersham) at 30°C for 40 min. The protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiographed after electroblotting onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with mouse anti-hIRE1α, anti-c-Myc, or anti-T7 antibody followed by goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Band intensities were measured by enhanced chemilumenescence and quantified using the NIH Image 1.55b program.

RNA analysis

Total RNA from transfected COS-1 cells was prepared at 50 h posttransfection (unless otherwise specified) using TRIzol reagent (Bethesda Research Labs, Rockville, MD). For Northern analysis, RNA samples (10 μg) were electrophoresed on 1% formaldehyde agarose gels and transferred onto a Hybond nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia) for hybridization (Tirasophon et al. 1998). 32P-labeled probes were prepared using the random prime labeling system (Amersham Pharmacia). Primer extension was performed as described by Sambrook et al (1989).

In vitro cleavage of HAC1 RNA

In vitro cleavage of HAC1 mRNA was performed as described previously by Sidrauski and Walter (1997) with modifications (Tirasophon et al. 1998).

UPR reporter assays

Each 100 mm plate of COS-1 cells was cotransfected with BIP-luciferase reporter plasmid (2 μg), SV40-β-gal (1 μg, Promega, Madison, WI), and wild-type or mutant pED-hIRE1 expression plasmids (6 μg each) by the calcium phosphate procedure (Tirasophon et al. 1998). In some experiments the ERP72 reporter plasmid (ERPTRE-CAT, kindly provided by Michael Green, St. Louis University, St. Louis, MO) replaced the BIP-luciferase reporter plasmid. At 52 h posttransfection, cells were treated with or without 10 μg/ml tunicamycin for 6 h and cell lysates were prepared. β-galactosidase activity assays (Promega, Madison, WI), CAT ELISA assays (Boehringer Mannheim), and luciferase activity assays (Boehringer Mannheim) were performed according to manufacturer's instructions. The luciferase and CAT activities were normalized to β-galactosidase activity.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Chuan Yin Liu for critical reading of this manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL kaufmanr@umich.edu; FAX (734) 763-9323.

Article and publication are at www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.839400.

References

- Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM, Harding HP, Ron D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:326–332. doi: 10.1038/35014014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande R, Stern P, Diehn M, Shamu C, Osario M, Zuniga M, Brown PO, Ploegh H. Degradation of proteins from the ER of S. cerevisiae requires an intact unfolded protein response pathway. Mol Cell. 2000;5:729–735. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RE, Walter P. Translational attenuation mediated by an mRNA intron. Curr Biol. 1997;7:850–859. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman R, Sidrauski C, Walter P. Intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:459–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernokalskaya E, Dompenciel R, Schoenberg DR. Cleavage properties of an estrogen-regulated polysomal ribonuclease involved in the destabilization of albumin mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:735–742. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JL, Carroll SS, Blue ES, Viscount T, Kuo LC. Activation of RNase L by 2′,5′-oligoadenylates. Biophysical characterization. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19187–19192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Walter P. A novel mechanism for regulating activity of a transcription factor that controls the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1996;87:391–404. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Guerra M, Rivas C, Esteban M. Activation of the IFN-inducible enzyme RNase L causes apoptosis of animal cells. Virology. 1997;236:354–363. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Silverman RH. 2-5A-dependent RNase molecules dimerize during activation by 2-5A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4133–4137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— A bipartite model of 2-5A-dependent RNase L. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22236–22242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner AJ, Wasley LC, Raney P, Haugejorden S, Green M, Kaufman RJ. The stress response in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Regulation of ERp72 and protein disulfide isomerase expression and secretion. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:22029–22034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti DM, Welihinda A, Kaufman RJ, Lee AS. Conservation and divergence of the yeast and mammalian unfolded protein response. Activation of specific mammalian endoplasmic reticulum stress element of the grp78/BiP promoter by yeast Hac1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30402–30409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez TN, Sidrauski C, Dorfler S, Walter P. Mechanism of non-spliceosomal mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response pathway. EMBO J. 1999;18:3119–3132. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas IG, Wabl M. Immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein. Nature. 1983;306:387–389. doi: 10.1038/306387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH. Dimerization of cell surface receptors in signal transduction. Cell. 1995;80:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: Coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1211–1233. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RJ, Davies MV, Wasley LC, Michnick D. Improved vectors for stable expression of foreign genes in mammalian cells by use of the untranslated leader sequence from EMC virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4485–4490. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.16.4485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara T, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced mRNA splicing permits synthesis of transcription factor Hac1p/Ern4p that activates the unfolded protein response. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1845–1862. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.10.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Unconventional splicing of HAC1/ERN4 mRNA required for the unfolded protein response. Sequence-specific and non-sequential cleavage of the splice sites. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1802–1807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AS, Bell J, Ting J. Biochemical characterization of the 94- and 78-kilodalton glucose-regulated proteins in hamster fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:4616–4621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Leeds P, Ross J. Purification and characterization of a polysome-associated endoribonuclease that degrades c-myc mRNA in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25261–25271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Regulation of signal transduction and signal diversity by receptor oligomerization. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:459–463. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CY, Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. Ligand-independent dimerization activates the stress-response kinases IRE1 and PERK in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24881–24885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Ma W, Gething MJ, Sambrook J. A transmembrane protein with a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase activity is required for signaling from the ER to the nucleus. Cell. 1993;74:743–756. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90521-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Kawahara T, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T. Signalling from endoplasmic reticulum to nucleus: Transcription factor with a basic-leucine zipper motif is required for the unfolded protein-response pathway. Genes Cells. 1996;1:803–817. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muresan Z, Arvan P. Thyroglobulin transport along the secretory pathway. Investigation of the role of molecular chaperone, GRP94, in protein export from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26095–26102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikawa J, Yamashita S. IRE1 encodes a putative protein kinase containing a membrane-spanning domain and is required for inositol phototrophy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1441–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, Sidrauski C, Kaufman RJ, Walter P. A role for presenilin-1 in nuclear accumulation of Ire1 fragments and induction of the mammalian unfolded protein response. Cell. 1999;99:691–702. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81667-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl HL. Signal transduction from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cell nucleus. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:683–701. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shamu CE, Walter P. Oligomerization and phosphorylation of the Ire1p kinase during intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. EMBO J. 1996;15:3028–3039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidrauski C, Walter P. The transmembrane kinase Ire1p is a site-specific endonuclease that initiates mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1997;90:1031–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidrauski C, Cox JS, Walter P. tRNA ligase is required for regulated mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1996;87:405–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M, Lenny N, Green M. Identification of genomic sequences that mediate the induction of the endoplasmic reticulum stress protein, ERp72, by protein traffic. DNA Cell Biol. 1993;12:807–822. doi: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirasophon W, Welihinda AA, Kaufman RJ. A stress response pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus requires a novel bifunctional protein kinase/endoribonuclease (Ire1p) in mammalian cells. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1812–1824. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;101:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta CR, Miao F, Arn EA, Stevens SW, Ho CK, Rauhut R, Abelson JN. The yeast tRNA splicing endonuclease: A tetrameric enzyme with two active site subunits homologous to the archaeal tRNA endonucleases. Cell. 1997;89:849–858. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP, Ron D. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XZ, Harding HP, Zhang Y, Jolicoeur EM, Kuroda M, Ron D. Cloning of mammalian Ire1 reveals diversity in the ER stress responses. EMBO J. 1998;17:5708–5717. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Shen J, Arenzana N, Tirasophon W, Kaufman RJ, Prywes R. Activation of ATF6 and an ATF6 DNA binding site by the ER stress response. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27013–27020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welihinda AA, Kaufman RJ. The unfolded protein response pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Oligomerization and trans-phosphorylation of Ire1p (Ern1p) are required for kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18181–18187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrana JL, Attisano L, Wieser R, Ventura F, Massague J. Mechanism of activation of the TGF-β receptor. Nature. 1994;370:341–347. doi: 10.1038/370341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Haze K, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Identification of the cis-acting endoplasmic reticulum stress response element responsible for transcriptional induction of mammalian glucose-regulated proteins. Involvement of basic leucine zipper transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33741–33749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]