Abstract

Danggui, also known as Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels (Apiaceae), has been used in Chinese medicine to treat menstrual disorders. Over 70 compounds have been isolated and identified from Danggui. The main chemical constituents of Angelica roots include ferulic acid, Z-ligustilide, butylidenephthalide and various polysaccharides. Among these compounds, ferulic acid exhibits many bioactivities especially anti-inflammatory and immunostimulatory effects; Z-ligustilide exerts anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, neuroprotective and anti-hepatotoxic effects; n-butylidenephthalide exerts anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer and anti-cardiovascular effects.

Background

Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels (Apiaceae) (AS), the root of which is known in Chinese as Danggui (Figure 1), was first documented in Shennong Bencao Jing (Shennong's Materia Medica; 200-300AD) and has been used as a blood tonic to treat menstrual disorders [1]. Danggui is marketed in various forms worldwide [2,3]. Over 70 compounds have been identified from Danggui, including essential oils such as ligustilide, butylphthalide and senkyunolide A, phthalide dimers, organic acids and their esters such as ferulic acid, coniferyl ferulate, polyacetylenes, vitamins and amino acids. Z-ligustilide (water insoluble and heat stable), among which Z-butylidenephthalide and ferulic acid are thought to be the most biologically active components in AS [4] and are often used in quality control and pharmacokinetic studies of Danggui [3-6].

Figure 1.

A section of root of Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels (Apiaceae) used in Chinese medicine.

Z-ligustilide is the main lipophilic component of the essential oil constituents and a characteristic phthalide component of a number of Umbelliferae plants. Z-ligustilide is considered to be the main active ingredient of many medicinal plants, such as Danggui [7] and Ligusticum chuangxiong [8].

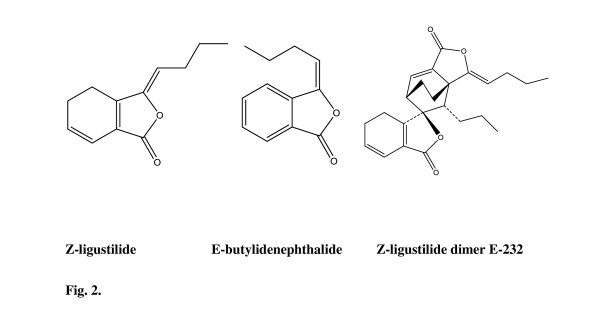

Phthalides

Phthalides (Figure 2) consist of monomeric phthalides such as Z-ligustilide and phthalide dimers. In 1990 Danggui was reported in the literature when the Z-ligustilide dimer E-232 was isolated [9]. The majority of the phthalides identified is relatively non-polar, the fraction of which can be extracted with solvents such as hexanes, pentane, petroleum ether, methanol, 70% ethanol and dichloromethane. The amount of Z-ligustilide in Danggui varies between 1.26 and 37.7 mg/g dry weight [6,10,11]. Z-ligustilide facilitates blood circulation, penetrates the blood brain barrier to limit ischemic brain damage in rats and attenuates pain behaviour in mice [12-14]. Preclinical studies have indicated that AS and Z-ligustilide may also relax smooth muscle in the circulatory, respiratory and gastrointestinal systems [15].

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of various identified phthalides found in Angelica sinensis.

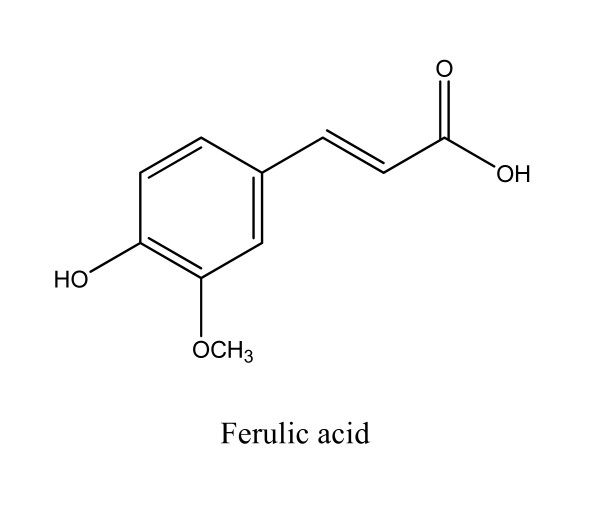

Organic acids

Danggui contains many organic acids. For example, ferulic acid (Figure 3) isolated from Danggui is widely used as the marker compound for assessing the quality of Danggui and its products. Methanol, methanol-formic acid (95:5), 70% methanol, 70% ethanol, 50% ethanol or diethyl ether-methanol (20:1) is used as the initial extraction solvent. The amount of ferulic acid in Danggui varies between 0.21 and 1.75 mg/g dry weight [6,16]. We recently extracted ferulic acid from AS using ethyl acetate and obtained 3.75 mg/g dry weight of the whole plant [11]. Abundant in rice bran, wheat, barley, tomato, sweet corn and toasted coffee, ferulic acid is an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer agent and apart from its effects against Alzheimer's disease, it possesses anti-hyperlipidemic, antimicrobial and anti-carcinogenic properties [17-21].

Figure 3.

Chemical structure of the major organic acid in Angelica sinensis.

Polysaccharides

Biochemical and medical researchers have recently been interested in the anti-tumor and immunomodulatory effects of polysaccharides [22]. The efficacy of Danggui is associated with its various polysaccharides [22] which are extracted with water as the initial extraction solvent. Polysaccharides from Danggui consist of fucose, galactose, glucose, arabinose, rhamnose and xylose [23]. Danggui contains a neutral polysaccharide and two kinds of acidic polysaccharides [24].

Pharmacological activities

Anti-inflammatory effects

Ferulic acid and isoferulic acid inhibit macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) production by murine macropharge RAW 264.7 cells, suggesting that these compounds contribute to the anti-inflammatory activity of AS [25,26]. Z-ligustilide also shows anti-inflammatory effects, probably related to inhibition of the TNF-α and NF-κB activities [27]. Using an NF-κB-dependent trans-activation assay as a pre-screening tool, our study demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effect of the ethyl acetate fraction of AS or Danggui [28]. AS suppresses NF-κB luciferase activity and decreases NO and PGE2 production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/IFN-γ-stimulated murine primary peritoneal macrophages. Ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide, two major compounds in AS, decrease NF-κB luciferase activity, which may contribute to the anti-inflammatory activity of AS [11]. Our in vivo study further confirmed that the ethyl acetate extract of AS inhibits the production of inflammatory mediators thereby alleviating acute inflammatory hazards and protecting mice from endotoxic shock [29]. Using a murine air pouch model, Jung et al. reported that the leukocyte count in the pouch exudate decreases in the BALB/c mice fed with 100 mg/kg body weight of a root extract (A. senticosus: AS: Scutellaria baicalensis), accompanied by a decrease in the neutrophil count, IL-6 mRNA level and TNF-α mRNA level in the pouch membrane and by decreased IL-6 and PGE2 concentrations in the pouch fluid and that the concentration of anti-inflammatory PGD2 in the pouch fluid increases as well [30]. Fu et al. reported that n-butylidenephthalide decreases the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α during LPS stimulated activation of murine dendritic cells 2.4 via the suppression of the NF-κB dependent pathways [31].

Anti-cancer effects

AS extract induces apoptosis and causes cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 in brain tumor cell lines [32]. AS extract also decreases the expression of the angiogenic factor vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in brain astrocytoma [33]. Moreover, n-butylidenephthalide and Z-ligustilide are cytotoxic against brain tumor cell lines [34] and leukemia cells [35]. The three main AS phthalides, namely n-butylidenephthalide, senkyunolide A and Z-ligustilide, decrease cell viability of colon cancer HT-29 cells dose-dependently [36]. Yu et al. reported that pretreatment of the PC12 cells with Z-ligustilide attenuates H2O2-induced cell death, attenuates an increase in intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) level, decreases Bax expression and cleaves caspase-3 and cytochrome C [37]. A novel polysaccharide (50 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg) isolated from AS inhibits the growth of HeLa cells in nude mice via an increased activity in the caspase-9, caspase-3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) [38].

Immunomodulatory effect

Treatment of BALB/c mice spleen cells with AS polysaccharide (100 μg/ml) increases the production of IL-2 and IFN-γ and decreases the production of IL-4 [39]. An acidic polysaccharide fraction isolated from AS stimulates female BALB/c murine peritoneal macrophages to produce higher levels of nitric oxide (NO) via the induction of iNOS gene expression [40]. The AS polysaccharide (mannose, rhamnose, glucuronic acid, galacturonic acid, glucose, galactose, arabinose, xylose)-dexamethasone conjugate demonstrates a therapeutic effect on trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced ulcerative colitis in rats and the systemic immunosuppression caused by dexamethasone [41]. Four hydrosoluble fractions of AS polysaccharide exert the most conspicuous mitogenic effects on phagocytic activity and NO production by female ICR mouse peritoneal macrophages [42]. AS polysaccharide treatment rescues BALB/c mice from retro-orbital bleeding induced anemia and increases IL-6, granulocyte-macrophages colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) concentrations in spleen cells [43].

Ferulic acid, an antioxidant from AS, decreases H2O2-induced IL-1β, TNF-α, matrix metalloproteinase-1 and matrix metalloproteinase-13 levels and increases SRY-related high mobility group-box gene 9 gene expression in chondrocytes [44]. AS induces the proliferation of ICR murine bone marrow mononuclear cells by activating ERK1/2 and P38 MAPK proteins [45]. Pretreatment with 50 mg/kg AS increases serum colony-stimulating activity together with IFN-γ and TNF-α levels in the spleen mononuclear cells of Listeria monocytogenes-infected BALB/c mice [46].

Anti-cardiovascular effects

Pre-treatment with AS (15 g/kg daily for 4 weeks) decreases doxorubicin-induced (15 mg/kg intravenously) myocardial damage and serum aspartate aminotransferase levels in male ICR mice [47]. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with AS water extract activate VEGF gene expression and the p38 pathway, thereby increasing angiogenic effects of HUVECs both in vitro and in vivo [48].

Excess adipose tissue can lead to insulin resistance and increases the risk of type II diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Water and 95% ethanol extracts of AS effectively decrease fat accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and reduce triglyceride content [49]. Yeh et al. demonstrated that n-butylidenephthalide is anti-angiogenic and is associated with the activation of the p38 and ERK1/2 signaling pathways [50].

Neuroprotective effects

Z-ligustilide treatment decreases the level of malondialdehyde (MDA) and increases the activities of the antioxidant enzymes glutathione peroxidise (GSH-Px) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the ischemic brain tissues in ICR mice; meanwhile there is a decrease in Bax and caspase-3 protein expression [51]. Z-ligustilide increases the choline acetyltransferase activity and inhibits the acetylcholine esterase activity in ischemic brain tissue from Wistar rats [52]. Huang et al. reported that AS extract protects Neuro 2A cell viability against β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide induced oxidative damage by ROS, MDA and glutathione (GSH) and rescues mitochondrial transmembrane potential levels [53]. Z-ligustilide inhibits the TNF-α-activated NF-κB signaling pathway, which may contribute to Z-ligustilide's protective effect against Aβ peptide-induced neurotoxicity in rats [54].

AS methanol extract significantly attenuates Aβ1-42 induced neurotoxicity and tau hyperphosphorylation in primary cortical neurons [55]. AS polysaccharides (18.6% saccharose) reduce myocardial infarction size and enhance cardiotrophon-1 levels, serum GSH levels, serum SOD levels, GSH-Px activity and brain caspase-12 expression in Wistar rats treated with a single oral dose (100, 200, 300 mg/kg) daily for two months [56].

A multi-herbal mixture composed of Panax ginseng, Acanthopanax senitcosus, AS and S. Baicalensis, HT008-1 down regulates COX-2 and OX-42 expression in the penumbra region [57].

Anti-oxidative activities

Water AS extract can be further purified into various AS polysaccharide fractions, such as a highly acidic polysaccharide fraction consisting of galacturonic acid. BALB/c murine peritoneal macrophages pretreated with various AS polysaccharide fractions alleviate the decrease in cell survival caused by tert-butylhydroperoxide, with an increased intracellular GSH content [58]. Furthermore, acidic polysaccharide fraction is also the most active fraction in terms of inhibiting the decrease in cell viability caused by H2O2. Acidic polysaccharide fraction also decreases the MDA formation, reduces the decline in SOD activity and inhibits the depletion of GSH in murine peritoneal macrophages caused by H2O2 [59]. Ethanol extract of AS combined with eight other Chinese herbs significantly increase the radical scavenging ability of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl hydrazine (DPPH) [60].

Anti-hepatotoxic effects

The liver contains a series of microsome hemoproteins called cytochrome P450s (CYPs). CYPs play an important role in the metabolic oxygenation of a variety of lipophilic chemicals including drugs, pesticides, food additives and environmental pollutants. The most important isoenzyme forms of cytochrome are CYP1A2 (13%), CYP2C (20%), CYP2D6 (2%), CYP2E1 (7%) and CYP3A (29%) [61]. Tang et al. reported that water and ethanol extracts of AS strongly increase the CYP2D6 and CYP3A activity in the microsome fraction of male Wistar rat livers [62]. Gao et al. demonstrated that treatment with Danggui Buxue Tang (DBT), which contains the roots of Astragali and AS, induces erythropoietin mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line Hep3B [63]. Dietz et al. reported that Z-ligustilide targets cysteine residues in human Keap1 protein thereby activating Nrf2 and the transcription of antioxidant response element (ARE) regulated genes and inducing NADPH:quinine oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) [64].

Kidney protective effects

There has been a 60% increase in the number of people needing treatment for chronic kidney disease between 2001 and 2010. Characterized by an increase in interstitial fibrosis and tubular epithelial cell atrophy, renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis is the common pathogenetic process of chronic kidney disease [65-67]. Angiotensin II appears to play a key role in several mechanisms involved in tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Angiotensin II up-regulates the expression of TGFβ1, a profibrotic cytokine involved in many of the events leading to renal fibrosis. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) can reduce renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis [68].

Oral administration of Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus and AS (14 g/kg/day) to Wistar rats increases the constitutive ROS activity in the kidneys. The treatment also enhances NO production via eNOS activation and the scavenging of ROS in the obstructed kidney in Wistar rats after unilateral ureteral obstruction [69]. In analysis with genechips, gene expression is induced, including transient receptor protein 3 (TRP3), bone marrow stromal cell antigen 1 (BST-1), peroxisomal biogenesis factor 6 (PEX6), xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH), CYP1A1, serine/cysteine proteinase inhibitor clade E member 1 (PAI-1) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). These genes may be involved in the increased degeneration of the extracellular matrix (ECM), decreasing ROS and regulating calcium phosphate metabolism [70]. Administration of Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus and AS into Sprague Dawley rats, as a unilateral ureteral obstruction model, decreases TGFβ1 levels, fibroblast activation, macrophage accumulation and tubular cell apoptosis [71]. Song et al. reported that oral administration of Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus and AS (12 g/kg/day) shows renoprotective effects, possibly associated with a reduction of proteinuria and up regulation of VEGF. These changes may have reduced the loss of capillaries and improve microstructure dysfunction in nephrectomized rats [72].

A study on 47 herbs of potential interest in the context of renal or urinary tract pathologies demonstrated that AS, Centella asiatica, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Scutellaria lateriflora and Olea europaea have strong antioxidant effects in tubular epithelial cells or apoptotic effects on renal mammalian fibroblasts or both [73].

Other effects

Ethanol extract of AS (100, 300 mg/kg) prolongs estrus in rats and the estrogenic activity of AS extract is likely due to the presence of Z-ligustilide [74]. A dichloromethane extract of AS exhibits a potent inhibitory effect on melanin production [75]. AS polysaccharide (ASP, 2.5 mg/day) enhances recovery in platelet, red blood cells and white blood cells counts in BALB/c mice after irradiation (4 Gy) [76]. ASP also reduces hepcidin expression by inhibiting signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3/5 and decapentaplegic protein (SMAD) 4 expression in the liver. Thus, ASP is suggested to be used for treating hepcidin-induced diseases [77].

Conclusion

Bioactive components extracted from AS roots include Z-ligustilide, ferulic acid and AS polysaccharides. Major pharmacological effects of Danggui extract or its components include anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, immunomodulatory, anti-cardiovascular, neuroprotective, anti-oxidative, anti-hepatotoxic and renoprotective activities.

Abbreviations

AS: Angelica sinensis; MIP-2: macrophage inflammatory protein-2; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; ROS: reactive oxygen species; JNK: c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; AP-1: activating protein-1; PARP: poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophages colony stimulating factor; ERK1/2: extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2; HUVEC: human umbilical vein endothelial cell; MDA: malondialdehyde; GSH-Px: glutathione peroxidise; SOD: superoxide dismutase; GSH: glutathione; DPPH: 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl hydrazine; CYP: cytochrome P450; Nrf2: nuclear factor E2-related factor 2; ARE: transcription of antioxidant response element; ACEi: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; TRP3: transient receptor protein 3; BST-1: bone marrow stromal cell antigen 1; PEX6: peroxisomal biogenesis factor 6; XDH: xanthine dehydrogenase; CYP1A1: cytochrome P450 subfamily I member A1; PAI-1: serine/cysteine proteinase inhibitor clade E member 1; FGF23: fibroblast growth factor 23; STAT3/5: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3/5.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

WWC and BFL searched the literature and wrote the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Wen-Wan Chao, Email: d91623701@ntu.edu.tw.

Bi-Fong Lin, Email: bifong@ntu.edu.tw.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by a grant (CCMP93-RD-052, CCMP94-RD-026, CCMP95-RD-105) from the Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Health, Taiwan.

References

- Monograph. Angelica sinenesis (Dong quai) Alternative Medicine Review. 2004;9(4):429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Burdette JE, Xu H, Gu C, van Breemen RB, Bhat KP, Booth N, Constantinou AI, Pezzuto JM, Fong HH, Farnsworth NR, Bolton JL. Evaluation of estrogenic activity of plant extracts for the potential treatment of menopausal symptoms. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:2472–2479. doi: 10.1021/jf0014157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao KJ, Dong TTX, Tu PF, Song ZH, Lo CK, Tsim KWK. Molecular genetic and chemical assessment of radix Angelica (Danggui) in China. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:2576–2583. doi: 10.1021/jf026178h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YL, Liang YZ, Chen BM, He YK, Li BY, Hu QN. LC-DAD-APCI-MS-based screening and analysis of the absorption and metabolite components in plasma from a rabbit administered an oral solution of danggui. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;383:247–254. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong ZB, Li SP, Hong M, Zhu Q. Hypothesis of potential active components in Angelica sinenesis by using biomembrane extraction and high performance liquid chromatography. J Pharm and Biomed Anal. 2005;38:664–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi L, Liang Y, Wu H, Yuan D. The analysis of Radix Angelicae sinensis (Danggui) J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:1991–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Zhu GD, Sun QM, Fang QC. Chemical studies of Angelica sinensis. Acta Pharmaceut Sin. 1979;14:529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito T, Ikeya Y, Okada M, Mistuhashi H, Maruno M. Two phthalides from Ligusticum chuanxiong. Phytochem. 1996;41:233–236. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00524-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LZ, He XG, Lian LZ, King W, Elliott J. Liquid chromatographic-electrospray mass spectrometric study of the phthalides of Angelica sinensis and chemical changes of Z-ligustilide. J Chromatogr A. 1998;810:71–79. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(98)00201-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gijbels MJM, Scheffer JJC, Svendsen AB. Analysis of phthalides from Umbelliferae by combined liquid-solid and gas-liquid chromatography. Chromatographia. 1981;14:452–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02263532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chao WW, Kuo YH, Li WC, Lin BF. The production of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 in peritoneal macrophages is inhibited by Andrographis paniculata, Angelica sinensis and Morus alba ethyl acetate fractions. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Yu Y, Ke Y, Wang C, Zhu L, Qian ZM. Ligustilide attenuates pain behavior induced by acetic acid or formalin. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;112:211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng HY, Du JR, Zhang GY, Kuang X, Liu YX, Qian ZM, Wang CY. Neuroprotective effect of Z-ligustilide against permanent focal ischemic damage in rats. Biol Pharmaceut Bull. 2007;30(2):309–312. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang X, Du JR, Liu YX, Zhang GY, Peng HY. Postischemic administration of Z-ligustilide ameliorates cognitive dysfunction and brain damage induced by permanent forebrain ischemia in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;88:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedge DE, Klun JA, Tabanca N, Demirci B, Ozek T, Baser KHC, Liu Z, Zhang S, Cantrell CL, Zhang J. Bioactivity-guided fractionation and GC/MS fingerprinting of Angelica sinensis and Angelica archangelica root components for antifungal and mosquito deterrent activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:464–470. doi: 10.1021/jf802820d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu GH, Chan K, Leung K, Chan CL, Zhao ZZ, Jiang ZH. Assay of free ferulic acid and total ferulic acid for quality assessment of Angelica sinensis. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1068:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.01.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan JJ, Cho JY, Kim HS, Kim KL, Jung JS, Huh SO, Suh HW, Kim YH, Song DK. Protection against β-amyloid peptide toxocoty in vivo with long-term administration of ferulic acid. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:89–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou L, Kong LY, Zhang XM, Niwa M. Oxidation of ferulic acid by Momordica charantia peroxidase and related anti-inflammation activity changes. Biol Pharmaceut Bull. 2003;26:1511–1516. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronchetti D, Impagnatiello F, Guzzetta M, Gasparini L, Borgatti M, Gambari R, Ongini E. Modulation of iNOS expression by a nitric oxide releasing derivative of the natural antioxidant ferulic acid in activated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;532:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan WLT, Cho CH, Rudd JA, Lin G. Study of the anti-proliferative effects and synergy of phthalides from Angelica sinensis on colon cancer cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudheer AR, Muthukumaran S, Devipriya N, Devaraj H, Menon VP. Influence of ferulic acid on nicotine induced lipid peroxidation, DNA damage and inflammation in experimental rats as compared to N-acetylcysteine. Toxicology. 2008;243:317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi VE, Liu F. Immunomodulation and anti-cancer activity of polysaccharide protein complexes. Curr Med Chem. 2000;7:715–729. doi: 10.2174/0929867003374705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QJ, Ding F, Zhu NN, He PG, Fang YZ. Determination of the compositions of polysaccharides from Chinese herbs by capillary zone electrophoresis with amperometric detection. Biomed Chromatogr. 2003;17:483–488. doi: 10.1002/bmc.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Tang J, Gu X, Li D. Water-soluble polysaccharides from Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels: preparation, characterization and bioactivity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2005;36:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai S, Ochiai H, Nakajima K, Terasawa K. Inhibitory effect of ferulic acid on macrophage inflammatory protein-2 production in a murine macrophage cell line, RAW264.7. Cytokine. 1997;9(4):242–248. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai S, Kawamata H, Kogure T, Mantani N, Terasawa K, Umatake M, Ochiai H. Inhibitory effect of ferulic acid and isoferulic acid on the production of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 in response to respiratory syncytial virus infection in RAW264.7 cells. Mediators of Inflammation. 1999;8:173–175. doi: 10.1080/09629359990513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Ning ZQ, Shan S, Zhang K, Deng T, Lu XP, Cheng YY. Phthalide lactones from Ligusticum chuanxiong inhibit lipopolysaccharide induced TNF-α production and TNF-α mediated NF-κB activation. Planta Medicine. 2005;71:808–813. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao WW, Kuo YH, Lin BF. Construction of promoters based immunity screening system and its application on the study of traditional Chinese medicine herbs. Taiwanese J Agric Chem Food Sci. 2007;45:193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Chao WW, Hong YH, Chen ML, Lin BF. Inhibitory effects of Angelica sinensis ethyl acetate extract and major compounds on NF-κB trans-activation activity and LPS-induced inflammation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;129:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung SM, Schumacher HR, Kim H, Kim M, Lee SH, Pessler F. Reduction of urate crystal uinduced inflammation by root extracts from traditional oriental medicinal plants: elevation of prostaglandin D2 levels. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2007;9:R64–72. doi: 10.1186/ar2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu RH, Hran HJ, Chu CL, Huang CM, Liu SP, Wang YC, Lin YH, Shyu WC, Lin SZ. Lipopolysaccharide stimulated activation of murine DC2.4 cells is attenuated by n-butylidenephthalide through suppression of the NF-κB pathway. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33(5):903–910. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0528-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai NM, Lin SZ, Lee CC, Chen SP, Su HC, Chang WL, Harn HJ. The antitumor effects of Angelica sinensis on malignant brain tumors in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3475–3484. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WH, Jin JS, Tsai WC, Chen YT, Chang WL, Yao CW, Sheu LF, Chen A. Biological inhibitory effects of the Chinese herb danggui on brain astrocytoma. Pathobiology. 2006;73:141–148. doi: 10.1159/000095560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai NM, Chen YL, Lee CC, Lin PC, Cheng YL, Chang WL, Lin SZ, Harn HJ. The natural compound n-butylidenephthaliude derived from Angelica sinensis inhibits malignant brain tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. J of Neurochem. 2006;99:1251–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QC, Lee JP, Jin WY, Youn UJ, Kim HJ, Lee IS, Zhang XF, Song KS, Seong YH, Bae KH. Cytotoxic cocstituents from Angelica sinensis radix. Archives of Pharmacol Res. 2007;30:565–569. doi: 10.1007/BF02977650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan WLT, Cho CH, Rudd JA, Lin G. Study of the anti-proliferative effects and synergy of phthalides from Angelica sinensis on colon cancer cells. J of Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Du JR, Wang CY, Qian ZM. Protection against hydrogen peroxide induced injury by Z-ligustilide in PC12. Exp Brain Res. 2008;184:307–312. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Li XQ, Wang X, Fan HT, Zhang XN, Hou Y, Liu SB, Mei QB. A novel polysaccharide, isolated from Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels induces the apoptosis of cervical cancer HeLa cells through an intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Phytomed. 2010;17:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Jia M, Meng J, Wu H, Mei Q. Immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharide isolated from Angelica sinensis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2006;39:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zhao Y, Wang H, Mei Q. Macrophage activation by an acidic polysaccharide isolated from Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;40(5):636–643. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2007.40.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Zhang B, Liu X, Teng Z, Huan M, Yang T, Yang Z, Jia M, Mei Q. A new natural Angelica polysaccharide based colon specific drug delivery system. J of Pharm Sci. 2009;98(12):4756–4768. doi: 10.1002/jps.21790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Duan JA, Qian D, Guo J, Song B, Yang M. Assessment and comparison of immunoregulatory activity of four hydrosoluble fractions of Angelica sinensis in vitro on the peritoneal macrophages in ICR mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PJ, Hsieh WT, Huang SH, Liao HF, Chiang BH. Hematopoietic effect of water soluble polysaccharides from Angelica sinensis on mice with acute blood loss. Experimental Hematology. 2010;38:437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MP, Yang SH, Chou CH, Yang KC, Wu CC, Cheng YH, Lin FH. The chondroprotective effects of ferulic acid on hydrogen peroxide stimulated chondrocytes: inhibition of hydrogen peroxide induced pro-inflammatory cytokines and metalloproteinase gene expression at the mRNA level. Inflamm Res. 2010;59:587–595. doi: 10.1007/s00011-010-0165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoping C, Jianghua C, Ping Z, Jizeng D. Angelica stimulates proliferation of murine bone marrow mononuclear cells by the MAPK pathway. Blood Cells Mol diseases. 2006;36:402–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz MLS, Torello CO, Constantino AT, Ramos AL, Queiroz JDS. Angelica sinensis modulates immunohematopoietic response and increases survival of mice infected with Listeria monocytogenes. J Med Food. 2010;13(6):1451–1459. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin YF, Zhou GL, Shen M, Chen YX, Liu SP, Chen GC, Chen H, You ZQ, Xuan YX. Angelica sinensis: a novel adjunct to prevent doxorubicin induced chronic cardiotoxicity. Basic & Clinical Pharmacol &Toxicol. 2007;101:421–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam HW, Lin HC, Lao SC, Gao JL, Hong SJ, Leong CW, Yue PYK, Kwan YW, Leung YH, Wang YT, Lee SMY. The angiogenic effects of Angelica sinensis extract on HUVEC in vitro and zebrafish in vivo. J of Cellular Biochem. 2008;103:195–211. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo AJ, Choi RC, Cheung AWH, Li J, Chen IX, Dong TT, Tsim KWK, Lau BWC. Stimulation of apolipoprotein A-IV expression in Caco-2/TC7 enterocytes and reduction of triglyceride formation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by potential anti-obesity Chinese herbal medicines. Chinese Medicine. 2009;4:5–12. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh JC, Cindrova-Davies T, Belleri M, Morbidelli L, Miller N, Cho CW, Chan K, Wang YT, Luo GA, Ziche M, Presta M, Charnock-Jones DS, Fan TP. The natural compound n-butylidenephthalide derived from the volatile oil of Radix Angelica sinensis inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Angiogenesis. 2011. on line. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kuang X, Yao Y, Du JR, Liu YX, Wang CY, Qian ZM. Neuroprotective role of Z-ligustilide against forebrain ischemic injury in ICR mice. Brain Res. 2006;1102:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang X, Du JR, Liu YX, Zhang GY, Peng HY. Postishemic administration of Z-ligustilide ameliorates cognitive dysfunction and brain damage induced by permanent forebrain ischemia in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;88:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SH, Lin CM, Chiang BH. Protective effects of Angelica sinensis extract on amyloid β-peptide induced neurotoxicity. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:710–721. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang X, Du JR, Chen YS, Wang J, Wang YN. Protective effect of Z-ligustilide against amyloid β-induced neurotoxicity is associated with decreased pro-inflammatory markers in rat brains. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zhao R, Qi J, Wen S, Tang Y, Wang D. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β by Angelica sinensis extract decreases β-amyloid induced neurotoxicity and tau phosphorylation in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:437–447. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, He B, Ge J, Li H, Luo X, Zhang H, Li Y, Zhai C, Liu P, Liu X, Fei X. Extraction, chemical analysis of Angelica sinensis polysaccharides and antioxidant activity of the polysaccharides in ischemia reperfusion rats. Int J Biol Macromol. 2010;47:546–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Y, Kwon S, Kim YT, Kim MY, Choi H, Kim JG, Jamarkattel-Pandit N, Dore S, Kim SH, Kim H. Neuroprotective effect of HT008-1, a prescription of traditional Korean medicine, on transient focal cerebral ischemia model in rats. Phytother Res. 2010;24:1207–1212. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zhao Y, Lv Y, Yang Y, Ruan Y. Protective effect of polysaccharide fractions from Radix A. sinensis against tert-Butylhydroperoxide induced oxidative injury in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;40(6):928–935. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2007.40.6.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zhao Y, Zhou Y, Lv Y, Mao J, Zhao P. Component and antioxidant properties of polysaccharide fractions isolated from Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30(10):1884–1890. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WJ, Li DP, Li JK, Li MH, Chen YL, Zhang PZ. Synergistic antioxidant activities of eight traditional Chinese herb pairs. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32(6):1021–1026. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedric G, Rachel B, Sarah W, Karine A. Inhibition of human P450 enzymes by multiple constituents of the Ginkgo biloba extract. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:1072–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JC, Zhang JN, Wu YT, Li ZX. Effect of the water extract and ethanol extract from traditional Chinese Medicines Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort. And Rheum palmatum L. on rat liver cytochrome P450 activity. Phytother Res. 2006;20:1046–1051. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao QT, Cheung JKH, Choi RCY, Cheung AWH, Li J, Jiang ZY, Duan R, Zhao KJ, Ding AW, Dong TTX, Tsim KWK. A Chinese herbal decoction prepared from Radix Astragali and Radix Angelica sinensis induces the expression of erythropoietin in cultured Hep3B cells. Planta Med. 2008;74:392–395. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz BM, Liu D, Hagos GK, Yao P, Schinkovitz A, Pro SM, Deng S, Farnsworth NR, Pauli GF, van Breemen RB, Bolton JL. Angelica sinensis and its alkylphthalides induce the detoxification enzyme NADPH: quinine oxidoreductase 1 by alkylating Keap1. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:1939–1948. doi: 10.1021/tx8001274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JL, Ma JZ, Louis TA, Collins AJ. Forecast of the number of patients with end-stage renal disease in the United States to the year 2010. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2753–2758. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12122753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Noble NA, Border WA. Therapeutic strategies to halt renal fibrosis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:177–181. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4892(02)00144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguid EI, Nahas A, Bello AK. Chronic kidney disease: the global challenge. Lancet. 2005;365:331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17789-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf G. Renal injury due to rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation of the transforming growth factor-beta pathway. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1914–1919. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Qu L, Tang J, Cai SQ, Wang H, Li X. A combination of Chinese herbs, Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus and Angelica sinensis, enhanced nitric oxide production in obstructed rat kidney. Vascular Pharmacol. 2007;47:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Putten VV, Qu L, Nemenoff RA, Shang MY, Cai SQ, Li X. Altered expression of gene profiles modulated by a combination of Astragali Radix and Angelicae sinensis Radix in obstructed rat kidney. Planta Med. 2010;76:1431–1438. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcikowski K, Wohlmuth H, Johnson DW, Gobe G. Effect of Astragalus membranaceus and Angelica sinensis combined with Enalapril in rats with obstructive uropathy. Phytother Res. 2010;24:875–884. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Meng L, Li S, Qu L, Li X. A combination of Chinese herbs, Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus and Angelica sinensis, improved renal microvascular insufficiency in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Vascular Pharmacol. 2009;50:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcikowski K, Wohlmuth H, Johnson DW, Rolfe M, Gobe G. An in vitro investigation of herbs traditionally used for kidney and urinary system disorders: potential therapeutic and toxic effects. Nephrol. 2009;14:70–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Circosta C, Pasquale RD, Palumbo DR, Samperi S, Occhiuto F. Estrogenic activity of standardized extract of Angelica sinensis. Phytother Res. 2006;20:665–669. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam RYY, Lin ZX, Sviderskaya E, Cheng CHK. Application of a combined sulphorhodamine B and melanin assay to the evaluation of Chinese medicines and their constituent compounds for hyperpigmentation treatment. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Li J, Meng FY, Liang SX, Deng R, Li CK, Pong NH, Lau CP, Cheng SW, Ye JY, Chen JL, Yang ST, Yan H, Chen S, Chong BH, Yang M. Polysaccharides from the root of Angelica sinensis promotes hematopoiesis and thrombopoiesis through the PI3K/AKT pathway. BMC Complement Alter Med. 2010;10:79–90. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KP, Zeng F, Liu JY, Guo D, Zhang Y. Inhibitory effect of polysaccharides isolated from Angelica sinensis on hepcidin expression. J of Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134(3):944–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]