Abstract

The present study investigated whether perception of receiving emotional support mediates the relationship between one partner’s giving of emotional support and the other partner’s depressive symptomatology using a population-based sample of 423 couples from the Changing Lives of Older Couples study. A path model was used guided by the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Results indicated that spouses’ giving emotional support was related to the degree to which their spouse reported receiving emotional support. Perception of receiving emotional support, in turn, was related to lower depressive symptomatology of the support recipient. Both husbands and wives can benefit from emotional support through their perception of receiving emotional support, and spouses’ perceptions, as well as their actions, should be considered in support transactions.

Keywords: Depressive Symptomatology, Emotional Support, Giving Support, Older Couples, Receiving Support

Introduction

There is a robust literature showing that married individuals are healthier, have fewer illnesses, are less depressed, and live longer than unmarried individuals, in part because they have social support from their spouses (Burman & Margolin, 1992; House, Landi, & Umberson, 1988), but few studies examine emotional support given and received in older couples’ relationships. We use data from the Changing Lives of Older Couples (CLOC) study to examine the interrelationships between older couple’s reports of giving and receiving emotional support in their marital relationship and depressive symptomatology. More specifically, we investigate one couple member’s report of giving emotional support to their spouse, their spouse’s perception of receiving emotional support, and vice versa and the interrelationships of these reports as related to depressive symptomatology. The goal of this paper is to capitalize on this unique data set to better understand how the perceptions of giving and receiving emotional support in older couples are related to their well-being.

Social support can be conceptualized in many different ways, but generally refers to the exchange of psychological and material resources between an individual and his or her social network members, with the intention of enhancing an individual’s ability to cope with stress (Cohen, 2004). Social support can promote positive psychological states, such as positive affect and self-esteem, which are thought to induce health-promoting physiological responses in neuroendocrine and immune system functions (Cohen, 1988, 2004; Uchino, 2006). Social support can also influence health by eliminating or buffering the effects of stressful experiences, thereby promoting less-threatening interpretations of adverse events and bolstering effective coping strategies (Cohen, 2004; Bass, McClendon, Brenna, & McCarthy, 1998). In marital relationships, support exchanged between husbands and wives can directly influence health and also can serve as a buffer against stressors that are external to the marital dyad (Burman & Margolin, 1992; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001).

Social support necessarily involves at least two people, one to provide and the other to receive; however, the support process as it operates between the support provider and the support receiver has not been adequately described. Previous studies investigating the support process found that one partner’s provision of support corresponded with his or her perception of receiving support from the other partner (Acitelli & Antonucci, 1994, Liang, Krause, & Bennett, 2001), and both were shown to be predictors of health (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003). In one study that investigated the social support process by modeling support provision, support receipt, and stress among younger couples, support provision and support receipt were shown to be positively correlated, but exerted unique and opposite effects on support receivers’ distress: giving support reduced distress, while receiving support increased distress (Bolger, Zuckerman, & Kessler, 2000). Findings from previous research provide considerable insight into the support process and the relationships between giving support, receiving support, and health. These interrelationships, however, have not been systematically examined. To address this gap, we investigated the idea that a support recipient’s perceptions of receiving emotional support may mediate the association between a social network member’s reports of giving emotional support and the support recipient’s depressive symptomatology. In the present study, such mediation would be indicated if the association between one spouse’s report of giving emotional support and their partner’s depressive symptomatology is mediated by the partner’s report of receiving emotional support, as shown in Figure 1.

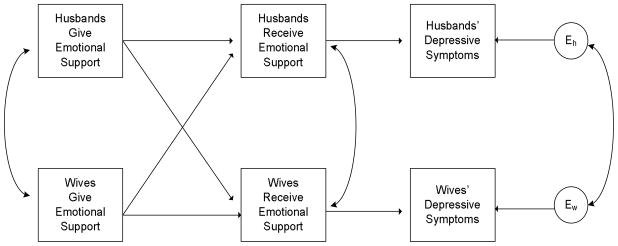

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model of the relationships between giving emotional support, receiving emotional support, and depressive symptomatology in husbands and wives.

Social support and depressive symptomatology among older adults

Understanding the relationship between giving and receiving emotional support in older couples is particularly important for several reasons. First, the benefits of emotional support from one’s partner become more important as people age, because social networks tend to become smaller over time (Carstensen, 1992; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004). Older individuals appear to purposely shift the focus of their relationships, interacting and maintaining social ties with those who are closest to them (Carstensen, 1992; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004). Social networks also shrink through retirement, the deaths of family members and friends, and limitations to social activity due to declining health (Bruce, 2002). In these circumstances, spouses often become the primary and most influential support provider (Carstensen, 1992; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004), underscoring the need to study how support operates within older couples (Acitelli &Antonucci, 1994; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004).

Second, older individuals are at higher risk for developing depressive symptomatology (Bruce, 2002; Glass, DeLeon, Bassuk, & Berkman, 2006). Depressive symptomatology is more prevalent in older adults because they are more likely to experience negative life events (e.g., loss of loved ones), functional limitations (e.g., declines in vision, hearing, and/or mobility), and health problems which may be irreversible. In addition, retirement may cause financial difficulties that can contribute to depressive symptomatology (Bruce, 2002; Glass et al., 2006). Research indicates that emotional support is the most effective type of support for reducing depression and depressive symptomatology in the event of such experiences (Bruce, 2002; Turner & Turner, 1999).

Third, although the protective effects of emotional support on depressive symptomatology have been well-documented, little is known about how support is given and received among older couples and how it may be related to depressive symptomatology. Furthermore, literature also reports conflicting findings on the beneficial effects of giving and receiving support on depressive symptomatology (Bolger et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2003). Some studies have reported that giving more support lessened support recipients’ distress during stressful situations among both younger and older individuals (Bolger et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2003). Other studies have found that people’s well-intentioned attempts to give support may fail or may even make matters worse for the person under stress (Bolger et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2003; Coyne et al., 1988). Studies on the effects of support on recipients’ health among younger and older individuals also have reported conflicting findings. For example, support can increase support recipients’ depressive symptomatology, making support recipients feel unskilled in coping with a stressor and overly dependent on others (Liang et al., 2001; Lindorff, 2000; Lu & Argyle, 1992).

Lastly, previous research has noted gender differences in how older husbands and wives perceive the giving and receiving of support. In one study, husbands reported giving more support to their wives than wives reported giving to their husbands, yet wives reported receiving less support from their husbands than their husbands reported receiving from their wives (Depner & Ingersoll-Dayton, 1985). Such discrepancies between husbands’ and wives’ reports of support given and received, as well as the potential vulnerability of older adults to depressive symptomatology and the conflicting findings about the benefit of support, all necessitate further study of the social support process among older couples, especially studies incorporating reports from both couple members.

The present study

By including the perspectives of both couple members as emotional support providers and recipients, the present study fills gaps in the literature on how emotional support operates in older married couples. Specifically, it enhances our knowledge of the relationship between social support and depressive symptomatology by conceptualizing the perception of receiving emotional support as a mediator variable between one spouse’s report of giving emotional support and the other spouse’s depressive symptomatology. A mediator variable helps explain the mechanism through which a predictor variable is able to influence the outcome variable (MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000; Baron & Kenny, 1986).

The conceptual model shown in Figure 1 is a general organizing framework for understanding the social support process through the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kashy & Kenny, 1999). The APIM is a dyadic data-analytic approach that allows estimation of effects for both members of the couple simultaneously, while controlling for the interdependence between them (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). The APIM also enables researchers to test the interpersonal effects of a participant’s own reports of giving emotional support on their own (actor effect) and their spouse’s (partner effect) depressive symptomatology, while taking into account the dyad’s interdependence. Figure 1 indicates whether the relationship between a spouse’s report of giving emotional support and his or her partner’s depressive symptomatology is mediated by the partner’s perception of having received emotional support, controlling for the partner’s giving emotional support (Kane, Jaremka, Guichard, Ford, Collins, & Freeny, 2007). While previous studies have examined the relationship between giving support, receiving support, and health, they have done so in a non-mediational framework (Bolger et al., 2000) or have used individuals as the unit of analysis (Brown et al et al., 2003). The current study examines the indirect relationship, i.e., mediational relationship, of the emotional support process on depressive symptomatology among older couples.

Using the data from the Changing Lives of Older Couples (CLOC) study, we addressed the following research questions: (1) Is the association between emotional support given by husbands and wives’ depressive symptomatology mediated by wives’ own perceptions of receiving emotional support? And (2) Is the association between emotional support given by wives and husbands’ depressive symptomatology mediated by husbands’ own perceptions of receiving emotional support? We hypothesized that the relationship between husbands’ and wives’ own reports of giving emotional support would be associated with less depressive symptomatology in their spouses, through the spouses’ perception of receiving emotional support.

Methods

Sample

Data were derived from the CLOC study, a prospective study of widowhood conducted from June 1987 to April 1988 in Michigan. Researchers used two-staged area probability sampling from the Detroit Standardized Metropolitan Area to collect information from married individuals. Eligible participants spoke English, were married, and were not institutionalized, and the husband in each couple was age 65 or older. Of those sampled, 1,532 individuals completed a baseline interview, a 68% response rate which is consistent with response rates from other Detroit-area studies (Carr, House, Kessler, Nesse, Sonnega, & Wortman, 2000; Carr, House, Wortman, Nesse, Kessler, 2001).

Researchers conducted face-to-face interviews averaging 2.5 hours per person during a 10-month period between June 1987 and April 1988. Of the 1,532 individuals who completed the baseline interview, 846 were members of married couples (423 couples) in which both husband and wife were interviewed. The other 686 participants were married individuals whose spouses were not interviewed. Analyses conducted for this project were restricted to the 423 married couples interviewed at baseline.

Demographic characteristics did not differ significantly between husbands and wives, except on age and education. Overall, husbands were older (p<.01) than their wives. The mean age for husbands was 82.93 (SD = 5.35); for wives it was 78.83 (SD = 6.13) (p<.01). Husbands were also more educated than their wives, with 62% having completed at least some high school, compared to 48% of wives (p<.05). Most participants were white (88%), U.S. born (89%), had been married an average of 52 years (±13 years), and averaged 2 to 3 children. The majority reported good or excellent health. More husbands than wives, however, experienced limitations in their daily activities due to health (35% vs. 30%, p< .05).

Measures

Depressive symptomatology

Depressive symptomatology was a self-reported measure using a subset of nine negative items from the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Study Depression (CES-D) scale (Radloff, 1977) measuring the degree to which participants had experienced depressive symptomatology during the past week. Examples included “I felt depressed” and “I felt lonely.” Response categories were 1 = hardly ever, 2 = some of the time, or 3 = most of the time. The scale was standardized, and higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms. The items showed good internal consistency (α = .76). This measure has been previously reported in the literature using the CLOC data (Carr et al. 2000, 2001).

Perception of giving emotional support

The primary predictor variable, giving emotional support, was measured with items from the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976). The two questions were “How much do you think you make your (husband/wife) feel loved and cared for?” and “How much are you willing to listen when your (husband/wife) needs to talk about (his/her) worries or problems?” The mean was calculated for these two questions. Response options were 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = some, 4 = quite a bit, and 5 = not at all a great deal. Higher scores indicated more support given as reported by the support providers. This measure was previously reported in secondary analyses of the CLOC data (Brown et al., 2003).

Perception of receiving emotional support

The potential mediator variable, perception of receiving emotional support, also came from the Dyadic Adjustment Scale. The two-item measure of perceived emotional support from a spouse was identical to the measure of giving support, except that participants were asked whether their spouse made them feel loved and cared for, and whether their spouse was willing to listen if they needed to talk. The mean was calculated for these two items, and higher scores indicated more support perceived by the support recipient. These measures have been used to assess emotional support from a spouse, which includes both feeling emotionally supported and feeling free to have an open discussion (Rankin-Esquer, Deeter, & Taylor, 2000).

Control variables

To control for the possibility that the effect of giving support and receiving support on depressive symptomatology may be due to a spouse’s characteristics, we included a variety of demographic variables. Age was collected as a continuous variable and calculated using the date of birth and the date of the interview. Education was assessed as highest grade of school completed, and used as a categorical variable with the options of 1= no high school, 2= some high school or high school degree, and 3 = more than high school. Race was measured as white, Black, American Indian, Asian, and other, and was categorized as white versus another race/ethnicity. Born in the U.S. was measured by asking in what foreign country the respondents were born, and used by categorizing those born in the U.S. versus those born outside the U.S.

Confounding variables

The analysis controlled for four possible confounding variables (i.e., health status, functional limitation, death of loved ones, and number of comorbidities) that were linked to depressive symptomatology (Bruce, 2002; Glass et al., 2006). Health status was measured using one question based on the Center for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) concerning health-related quality of life. The question asked “How would you rate your health at the present time?” Response options were 1= excellent, 2 = very good, 3 = good, 4 = fair, and 5 = poor. Functional limitation was also measured with one question from BRFSS: “How much are your daily activities limited in any way by your health or health-related problems?” Response categories ranged from 1= not at all, to 5 = a great deal. Death of loved ones was measured with two questions: “Did a parent, brother, or sister die in the past 12 months?” and “Did someone else you felt very close to die in the past 12 months?” If participants answered yes to either of these questions, they were coded as having lost a loved one to death. Number of comorbidities was measured by asking whether the participants have had arthritis or rheumatism, a lung disease, hypertension, a heart attack or other heart trouble, or diabetes or high blood sugar during the last 12 months. Reports of co-morbidities were summed, and ranged from 0 to 5.

Analysis approach

Analyses were conducted using M-PLUS software version 4.2. Created by Muthén and Muthén, M-PLUS allows for examination of multiple relationships between a number of predictor and outcome variables. We constructed a path analysis with observed measures of study variables instead of latent variable models, because our social support variables had only two items. Our analyses treated the dyad as the unit of analysis (i.e., the number of couples, rather than individuals, was used to calculate the degrees of freedom) because of the interdependence of the data on the couple-level effect on depressive symptomatology (ICC= 0.18, p<.0001).

Model fit

Multiple indices were used to assess model fit. These included the Chi-square test statistic, the Root-Mean-Square-Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Standardized Root Square Mean Residual (SRMR), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI). With a large sample size, the Chi-square test is not a reliable method for assessing model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Thus, we relied on standard cutoff recommendations for the RMSEA, SRMR, CFI, and TLI (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For the RMSEA and the SRMR, values approximating .05 indicate close fit. For the CFI and the TLI, values greater than or equal to .95 suggest a model with proportionate improvement in fit from the baseline model.

Model specification

An Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) was constructed with structural equation modeling (SEM) as specified by the conceptual model guiding this research. That is, husbands’ and wives’ reports of giving emotional support were specified as predictor variables, husbands’ and wives’ reports of receiving emotional support as mediator variables, and husbands’ and wives’ depressive symptomatology as outcome variables (Kashy & Kenny, 1999). Demographic characteristics that were significantly different between husbands and wives (i.e., age, education) and other covariates that may affect emotional support and depressive symptomatology (i.e., self-reported health, functional limitation, death of loved ones, and number of comorbidities) were adjusted in the model. We also specified interdependence between husbands’ and wives’ giving emotional support, receiving emotional support, and depressive symptomatology. Correlations among the variables are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Correlation among emotional support measures and depressive symptomatology in husbands and wives

| Wives reports | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giving emotional support | Receiving emotional support | Depressive symptoms | ||

| Husbands reports | Giving emotional support | 0.32** | 0.56** | −0.18* |

| Receiving emotional support | 0.59** | 0.39** | −0.28** | |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.17* | −0.22** | 0.17* | |

Note. Correlations for wives appear above the diagonal; correlations for husbands appear below the diagonal. Correlations between husbands and wives are in bold.

p < .05;

p < .01.

Next, we examined gender differences in the mediation effect by building nested models. Model 1 (initial model) was built by constraining the actor effects and the partner effects to be equal. Model 2 was built to test whether the actor effects differed for husbands and wives by removing the equality constraint on paths a, b, c, and d. Model 3 tested whether the partner effects differ for husbands and wives by removing the equality constraint on paths f and e. Of these, the model that provided the best fit to the data was selected.

Results

Comparison of husbands and wives on the study variables

Means and standard deviations for husbands and wives are presented in Table 1. There were significant gender differences in reports of receiving emotional support and depressive symptomatology. Husbands reported receiving more emotional support from their wives than wives reported receiving from their husbands (p <.001). Wives also reported feeling more depressed than did husbands (p <.05). No significant gender difference was found in giving emotional support.

TABLE 1.

Means, standard deviations, and tests of gender differences among husbands and wives

| Variable | Wives (n=423) | Husbands (n=423) | t-value | df | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | ||||

| Giving emotional support | 4.19 | 0.71 | 3.48–4.90 | 4.14 | 0.74 | 3.40–4.88 | 1.36 | 415 | .17 |

| Receiving emotional support | 4.02 | 0.92 | 3.10–4.94 | 4.28 | 0.83 | 3.45–5.00 | −5.39 | 419 | <.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.07 | 0.98 | −0.91–1.07 | −0.10 | 0.98 | −1.08-0.88 | 2.85 | 422 | <.05 |

Note. Eight couples (16 individuals) had missing values for giving emotional support. Four couples (8 individuals) had missing values for receiving emotional support. One couple (2 individuals) had missing values for depressive symptoms.

Correlations among the husbands’ and wives’ variables

The correlations among giving emotional support, receiving emotional support, and depressive symptomatology are presented in Table 2. Correlations for husbands are reported below the diagonal, and correlations for wives above the diagonal. Correlations between partners on each variable (i.e., within-dyad correlations) are displayed along the diagonal. Partners’ scores on giving emotional support, receiving emotional support, and depressive symptomatology were significantly but modestly correlated.

For both husbands and wives, their own reports of giving emotional support to their spouses were significantly correlated with their own perception of receiving emotional support, and with their partners’ reports of receiving emotional support from them. Husbands’ and wives’ own reports of giving emotional support were inversely correlated with their own as well as with their spouses’ depressive symptomatology. Husbands’ and wives’ reports of receiving emotional support were also inversely correlated with their own and their spouses’ depressive symptomatology.

Mediation effect of perception of receiving support

The APIM using SEM and testing the hypothesized relationship between giving emotional support, receiving emotional support, and depressive symptomatology adjusting for covariates and confounders had a good fit; χ2 (30, N = 423) = 32.29, CFI = .97, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .03, and SRMR = .02. One additional path was specified as indicated by the modification indices and was conceptually sensible (Bolin, 1989). This path correlated husbands’ age and husbands’ own perception of receiving emotional support. The modified model with one additional path improved the overall model fit with χ2 (29, N = 423) = 34.93, CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .02, and SRMR = .02. The additional path, however, was not statistically significant.

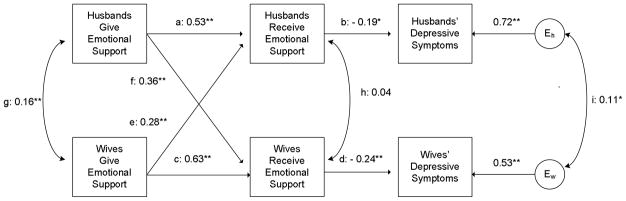

The APIM supported the hypothesis that husbands’ and wives’ own perceptions of receiving emotional support partially mediated the relationship between their spouses’ reports of giving emotional support and their own depressive symptomatology, as presented in Figure 2. Husbands reported receiving the emotional support that their wives gave (β = .28, p < .01; Path e), and receiving emotional support was negatively correlated with husbands’ depressive symptomatology (β = −.19, p < .05; Path b). Using the delta method (Bollen, 1989; Raykov & Marcoulides, 2004), we found a significant mediation effect for husbands’ perception of receiving support (Z = −2.50, p = .01), suggesting that the association between wives’ report of giving support and husbands’ depressive symptomatology partially operated through husbands’ perception of receiving emotional support.

FIGURE 2.

Actor-partner interdependence model of spouses’ giving emotional support, receiving emotional support, and depressive symptomatology, adjusting for age, education, health status, functional limitation, death of loved ones, and number of comorbidities. Unstandardized β weights for variables entered into the model are shown. Significant relationships are indicated by asterisks (*p < .05, **p < .01).

Similar results were found for wives. Wives perceived receiving the emotional support that their husbands gave (β = .36, p < .01; Path f), and this perception was negatively correlated with their own depressive symptomatology (β = −.24, p < .01; Path d). This mediation effect also was significant (Z = −3.60, p < .001) suggesting that the association between husbands’ report of giving emotional support and wives’ depressive symptomatology partially operated through wives’ perception of receiving emotional support.

Because our descriptive analysis showed significant differences between husbands and wives in receiving emotional support and depressive symptomatology, we built nested models to examine the effect of gender on our mediation model. This was done by building constraints causing the actor and partner effects to be equal.

The results of the nested models did not support an effect of gender on our mediation model. Model 1 with equal actor effects and partner effects across spouses provided a good fit to the data; χ2 (32, N = 423) = 37.73(ns), CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = 0.02, and SRMR = .02. The second model, relaxing the equality constraints for the actor effects, did not significantly improve model fit; χ2 (30, N = 423) = 35.49 (ns), CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .02, and SRMR = .02. Likewise, the third model, relaxing the equality constraints for the partner effects (with actor effects constrained to be equal), did not significantly improve model fit; χ2 (31, N = 423) = 36.06 (ns), CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .00, and SRMR = .02. We selected model 1 (the model with both actor and partner effects constrained); the model that showed no differences in the mediation effect between husbands and wives. Selection was based on model parsimony; that is, we selected a model with relatively few free parameters and more constraints (Preacher, 2006).

Relationship between giving emotional support and perception of receiving emotional support

Although not a primary focus of the current study, we examined four other relationships in the model to better understand the interrelationships of all the variables in the APIM: 1) the relationship between each spouse’s report of giving emotional support and their report of receiving emotional support (Path a and Path c); 2) the relationship between husbands’ and wives’ reports of giving emotional support (Path g); 3) the relationship between husbands’ and wives’ reports of receiving emotional support (Path h), and 4) the relationship between husbands’ and wives’ reports of depressive symptomatology (Path i). Both husbands’ and wives’ own reports of giving emotional support were related to their perceptions of receiving emotional support from their spouses, i.e., husbands’ giving emotional support was significantly related to their perception of having received emotional support from their wives (β = .58, p < .01; Path a), and the same was true for wives (β = .63, p < .01; Path c). There were also significant intra-couple correlations between husbands’ and wives’ giving emotional support (β = .16, p < .01; Path g) and depressive symptomatology (β = .11, p < .05; Path i).

Discussion

This study examined the interrelationships between giving and receiving emotional support and depressive symptomatology in older couples, guided by an Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. This model used the dyad as the unit of analysis and allowed for modeling of the interdependence between spouses’ own reports of support and depressive symptomatology. In accord with our hypothesis, perception of receiving support partially mediated the relationship between giving emotional support and depressive symptomatology for both husbands and wives. There was no gender difference in the mediation effect. In addition, our findings reflected the interdependence between spouses’ reported experiences of giving each other emotional support, receiving emotional support, and experiencing depressive symptomatology.

The findings from this study show that the perception of receiving emotional support can be an important component of the positive effect of giving emotional support on depressive symptomatology. Husbands and wives who perceived receiving support from their spouses were less depressed. Some other studies, however, have reported that receiving emotional support can lead to negative health outcomes (Bolger et al., 2000; Barbee, Cunningham, Winstead, Derlega, Gulley, Yankeelov, & Druen, 1993). Bolger and colleagues (2000) found that when support recipients were aware of receiving emotional support, there was an emotional cost or burden which could negatively affect health, but when support recipients did not perceive receiving support, it was beneficial. Hence, the researchers concluded that social support is most beneficial when it is “invisible,” i.e., when the support is unnoticed by the support recipient.

At first glance, the results of this study appear to contradict these findings. A closer examination, however, may help clarify how the emotional social support process operates differently among couples experiencing different life events. In the study conducted by Bolger and colleagues (2000), support recipients were experiencing a stressful event (i.e., preparation for a bar exam) which demanded a great deal of time and energy. Their support providers may have been empathetic and supportive, but recipients may have experienced guilt and a responsibility to reciprocate support, while being stretched for time and availability (Bolger et al., 2000). In the current study, however, the cost of receiving emotional support may have been negligible, as husbands and wives may not have been experiencing circumstances in which one partner was receiving more support than the other. In fact, husbands and wives reported giving support as much as they were receiving it. Similar findings have been reported in the literature, showing that receiving support is beneficial when the support recipient gives support back to his or her partner (Liang et al., 2001; Gleason, Iida, Bolger, & Shrout, 2003). Reciprocity is a fundamental function of close on-going relationships (Ingersoll-Dayton & Antonucci, 1988). Our findings support this notion among older couples.

There were other methodological factors that may have contributed to the differential findings between our study and Bolger et al. (2000). Bolger and colleagues examined far younger couples (mean age <30), and many had been together for only about three years. In contrast, the mean age of our study participants was 82 years old, and they had been married on average 52 years. The age of the participants and their length of marriage may have affected how they perceived the emotional support given and received in their relationship, and these older couples may have developed more successful strategies to communicate their emotional support to one another. Future studies that go beyond interview and survey methodology could examine how older couples communicate and enact support, to better understand which strategies are more or less successful. Our conclusions are necessarily conditioned by the fact we have conducted a secondary analysis of survey data which was not originally collected to study the exchange of emotional support among the older couples that participated in the CLOC study.

The findings from this study may also be a reflection of changes in the social networks of older couples and a resulting increase in the interdependence between husbands and wives as they grow older. Carstensen (1992) reported that as people age, they actively increase their emphasis on emotionally close and significant relationships. For the participants in the CLOC study, social networks may have become smaller, and partners may have drawn closer to each other (Carstensen, 1992; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004), thereby increasing the interdependence of emotional social support between spouses. In addition, this interdependence may be a reflection of length of marriage. Perhaps these couples had remained married for an average of 52 years because they were skilled at mutually giving and receiving emotional support.

This study also found interdependence in husbands’ and wives’ reports of depressive symptomatology. This phenomenon has been widely reported in the literature, i.e., an emotional experience of a family member has been shown to affect other members (Broderick, 1993). In fact, in close relationships, emotions have been found to be “contagious,” and individuals often unconsciously reflect the emotions that their partners experience (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1994; Tower & Kasl, 1996). Alternatively, older couples may have been experiencing similar negative life events within and outside their marital relationships. For example, older husbands and wives may be struggling with their own and each others’ health and financial concerns (Bruce, 2002; Glass et al., 2006), and they may be losing friends due to death (Bruce, 2002; Glass et al., 2006). The interdependence between couples’ reports of giving support and experiencing depressive symptomatology highlights the importance of collecting information on both couple members and capturing interdependence with APIM. These interpretations suggest that when depressive symptomatology is experienced by one spouse in late life marriage, the partner may be at risk as well, due to either intra-couple dynamics or external factors that impinge on the couple. Future studies that retain the older couple as the unit of analysis and follow them over time, measuring both intra-couple processes and external social stresses, can help determine if the interdependence evidenced in this sample holds true. Because of the cross-sectional nature of our analyses, we cannot rule out any cohort effects that may have been present. Research indicates, however, that emotional support does not decrease with age when cohort designs are used (Due, Holstein, Lund, Modvig, & Avlund, 1999), suggesting that cohort effects may not account for the present findings.

This study did not find gender differences in the mediation effect. Further, the perception of receiving emotional support was a mediator for both husbands and wives. Although husbands’ and wives’ experiences of giving and receiving emotional support may be different on a day-today basis, the spouses in this study may have evaluated their exchange of emotional support globally, rather than keeping an account of each time they gave and received support (Franks, Wendorf, Gonzalez, & Ketterer, 2004). Hence, the support that husbands and wives perceived may have been a reflection of the past 50 years of giving and receiving support, including what they give and receive today, have given and received in the past, and expect to give and receive in the future (Franks et al., 2004). Additionally, over time, older couples may have developed strategies to show more affection towards one another and avoid escalation of negative emotions (Carstensen, Gottman, & Levenson, 1995). Husbands and wives reports of giving and receiving emotional support may be a reflection of an increase in emotional closeness in their marital relationship as their social network shrinks and they increasingly emphasize this most significant relationship (Cartensen, 1992; Lockenhoff & Cartensen, 2004).

This study has a number of important limitations. Findings should be considered in light of its cross-sectional nature. Our analyses examined only the CLOC study baseline data; replications with longitudinal data are required to account for temporality between reports of giving emotional support, receiving emotional support, and depressive symptomatology. However, we were able to demonstrate an association between giving emotional support, receiving emotional support, and depressive symptomatology, a relationship suggested in the past but not previously tested in older married couples (Acitelli & Antonucci, 1994; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004). Additionally, an alternative model may be plausible. For instance, married individuals who are depressed may view their social world more negatively and thus perceive less support as being available from their spouses. Future studies may include test of alternative models to expand our understanding of social support and depressive symptomatology among older couples.

We chose to conduct a secondary analysis of the CLOC data set because it is unique in that a number of social, health, and behavior variables were collected on a probability sample of older couples. Due to the sample size, however, many measures were shortened versions of longer measures, possibly limiting comparisons to other studies of social support in late life. Although we compared our findings with those of Bolger et al. (2000), our study differed from their study in several methodological ways. As Bolger and colleagues did, future studies of older couples could consider using daily diary methods to record reports of giving and receiving support and depressive symptomatology near the time they occur, to capture the interactions on a day-to-day basis, minimize retrospective recall bias, and decrease global assessment of the variables under study.

Overall, our study findings underscore the importance of dyadic research approaches to understanding the relationship between giving and receiving support and depressive symptomatology among older couples, using a mediation model. Our findings revealed that the effect of spouses’ perception of receiving emotional support on their depressive symptoms was influenced not only by the behavior of their partners, but also by their own engagement in giving support to their partners. We also found interdependence among older couples in exchange of emotional support and in depressive symptomatology. Our findings underscore the need expressed by others for more couple-based studies to investigate dyadic interactions, particularly of older couples and late life marriages who may be studied less frequently (e.g, Acitelli & Antonucci, 1994; Bolger et al., 2000; Franks et al., 2004).

Finally, our findings can inform future intervention research. Interventions focused on enhancing older adults’ social, emotional, and physical health might be improved by efforts focused on both members of couples (Lewis, DeVellis, & Sleath, 2002), thereby increasing effectiveness and reach. Programs might focus on increasing the social participation of couples, or involving them in health promotion activities together.

As the study of social support among older couples continues to evolve, special attention should be paid to the exchange of other types of support, such as the effect of caregiving on depressive symptomatology for both couple members, or the exchange of tangible instrumental support, between husbands and wives. Using a dyadic framework may yield a more comprehensive understanding of who benefits from what type of support and why, as well as the potential influence of exchanging social support on mental and physical health. Our findings suggest that continued study of the support exchanged in older couples is warranted and could extend our understanding of support mechanisms as related to health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

The CLOC study was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (P30-MH38330) and the National Institute for Aging (R01-AG15948-01A1). This project was supported in part by the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Cancer Control Education Program (R25 CA057726). The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Kathryn Remmes Martin, Ms. Zoe Enga, and Dr. Joan Walsh for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Jo Anne Earp and members of her manuscript writing course for their review of earlier drafts. The authors would also like to express our appreciation to Camille Wortman, James House, Ronald Kessler, and Jim Lepowski, the original investigators of the Changing Lives of Older Couples Study.

Contributor Information

Linda K. Ko, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Megan A. Lewis, RTI International

References

- Acitelli LK, Antonucci TC. Gender differences in the link between marital support and satisfaction in older couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:688–698. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbee AP, Cunningham MR, Winstead BA, Derlega VJ, Gulley MR, Yankeelov PA, Druen PB. Effects of gender-role expectations on the social support process. Journal of Social Issues. 1993;49:175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass DM, McClendon MJ, Brenna PF, McCarthy C. The buffering effect of a computer support network on caregiver strain. Journal of Aging and Health. 1998;10:20–43. doi: 10.1177/089826439801000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A, Kessler RC. Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: A Wiley-Interscience Publication; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick CB. Understanding family processes: Basics of family systems theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Nesse RM, Vinokur AD, Smith DM. Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it. American Psychological Society: Psychological Science. 2003;14:320–327. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M. Psychological risk factors for depressive disorders in late life. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman B, Margolin G. Analysis of the association between marital relationships and health problems: An interactional perspective. Psychology Bulletin. 1992;112:39–63. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, House JS, Kessler RC, Nesse RM, Sonnega J, Wortman C. Marital quality and psychological adjustment to widowhood among older adults: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2000;56B:S197–S207. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.s197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, House JS, Wortman C, Nesse R, Kessler R. Psychological adjustment to sudden and anticipated spousal loss among older widowed persons. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2001;56B:S237–S248. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.s237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioeconomic selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:331–338. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Gottman JM, Levenson RW. Emotional behavior in long-term marriage. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:140–149. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Psychological models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology. 1988;7:269–297. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist. 2004;59:676–84. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Wortman CB, Lehman DR. The other side of support: Emotional overinvolvement and miscarried helping. In: Gottlieb BH, editor. Marshalling social support. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 305–330. [Google Scholar]

- Depner CE, Ingersoll-Dayton B. Conjugal social support: Patterns in later life. Journal of Gerontology. 1985;40:761–766. doi: 10.1093/geronj/40.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Due P, Holstein B, Lund R, Modvig J, Avlund K. Social relations: Network, support and relational strain. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48:661–673. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks MM, Wendorf CA, Gonzalez R, Ketterer M. Aid and influence: Health-promoting exchanges of older married partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2004;21:431–445. [Google Scholar]

- Glass T, De Leon CF, Bassuk SS, Berkman LF. Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: Longitudinal findings. Journal of Aging and Health. 2006;18:604–628. doi: 10.1177/0898264306291017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason ME, Iida M, Bolger N, Shrout PE. Daily supportive equity in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;29:1036–1045. doi: 10.1177/0146167203253473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL. Emotional contagion. Paris: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landi KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll-Dayton B, Antonucci T. Reciprocal and non-reciprocal social support: Contrasting sides of intimate relationships. Journal of Gerontology. 1988;43:65–73. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.3.s65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane HS, Jaremka LM, Guichard AC, Ford MB, Collins NL, Feeney BC. Feeling Supported and feeling satisfied: How one partner’s attachment style predicts the other partner’s relationship experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:535–555. [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Kenny DA. The analysis of data from dyads and groups. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton T. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychology Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, DeVellis B, Sleath B. Interpersonal communication and social influence. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 3. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2002. pp. 363–402. [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Krause NM, Bennett JM. Social exchange and well-being: Is giving better than receiving? Psychology and Aging. 2001;16:511–523. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindorff M. Is it better to perceive than receive? Social support, stress, and strain for managers. Psychology, Health, and Medicine. 2000;5:271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lockenhoff CE, Carstensen LL. Socioemotional selectivity theory, aging, and health: The increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. Journal of personality. 2004;72:1395–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Argyle M. Receiving and giving support: Effects on relationship and well-being. Counseling Psychology Quarterly. 1992;5:123–133. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ. Quantifying parsimony in structural equation modeling. Multivariate. 2006;41:227–259. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4103_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:381–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin-Esquer L, Deeter A, Taylor C. Coronary heart disease and couples. In: Schmaling K, editor. The psychology of couples and illness: Theory, research, & practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov T, Marcoulides G. Using the delta method for approximate interval estimation of parameter functions in SEM. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2004;11:621–637. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tower RB, Kasl SV. Depressive symptoms across older spouses: Longitudinal influences. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:683–697. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Turner JB. Social integration and support. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of sociology of mental health. New York: Kluwer Academic; 1999. pp. 301–319. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29:377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]