Abstract

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) is a life-threatening complication of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). NF1 is caused by mutation in the gene encoding neurofibromin, a negative regulator of Ras signaling. There are no effective pharmacologic therapies for MPNST. To identify new therapeutic approaches targeting this dangerous malignancy, we developed assays in NF1+/+ and NF1−/ − MPNST cell lines and in budding yeast lacking the NF1 homologue IRA2 (ira2Δ). Here we describe UC1, a small molecule that targets NF1−/− cell lines and ira2Δ budding yeast. Using yeast genetics we identified NAB3 as a high-copy suppressor of UC1 sensitivity. NAB3 encodes an RNA binding protein that associates with the C-terminal domain of RNA Pol II and plays a role in the termination of non-polyadenylated RNA transcripts. Strains with deletion of IRA2 are sensitive to genetic inactivation of NAB3, suggesting an interaction between Ras signaling and Nab3-dependent transcript termination. This work identifies a lead compound and a possible target pathway for NF1-associated MPNST, and demonstrates a novel model system approach to identify and validate target pathways for cancer cells in which NF1 loss drives tumor formation.

Keywords: Neurofibromatosis, budding yeast, Ras signaling, molecular therapeutics, high-throughput chemical screening

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common genetic disorders in humans, occurring in 1 in 3500 live births. NF1 is caused by inherited or de novo mutation in the NF1 tumor suppressor gene, which encodes a GTPase activating protein (GAP) for Ras signaling proteins. NF1 has a broad clinical spectrum: affected individuals can develop benign nervous system tumors called neurofibromas, low-grade astrocytomas, pheochromocytoma, and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (1). Plexiform neurofibromas occurring in deep nerves can degenerate into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs), a life-threatening consequence of NF1 (2, 3). The lifetime risk of MPNST in NF1 patients is estimated to be 8–15%, and the 5-year survival is approximately 20% (4–6).

Plexiform neurofibromas are heterogeneous, consisting of fibroblasts, perineurial cells, mast cells, and Schwann cells, but only Schwann cells have biallelic inactivation of NF1 (7). In mouse models, targeted deletion of NF1 from the Schwann cell lineage gives rise to neurofibromas (8–10). Thus, loss of NF1 from Schwann cell precursors is thought to initiate plexiform neurofibroma. Aberrant signaling occurs between NF1-deficient Schwann cells and NF1 heterozygous mast cells, which generates a tumorigenic microenvironment (8, 11, 12). Because of their role in the initiation of plexiform neurofibroma and progression to MPNST, NF1-deficient Schwann cells represent an ideal population for targeted molecular therapies.

Chemical screens have revolutionized the discovery process for targeted molecular therapies. However, primary Schwann cells are difficult to culture and present a challenge for high throughput screening. Another challenge in drug discovery is the rapid and efficient identification of the receptor for a novel compound – either the physical ligand, or the biological process that is being modified. Approaches addressing these challenges are needed to identify new compounds and target pathways for the devastating tumors that afflict NF1 patients.

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has two NF1 homologues, IRA1 and IRA2, which encode Ras-GTPase activating proteins (13). Deletion of an IRA gene increases Ras-GTP and activates of two pathways: a MAPK pathway that modifies cell morphology, and the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) pathway (14, 15). Schwann cells lacking NF1 have increased intracellular cAMP, and display PKA-dependent phenotypes (16, 17). The fact that Schwann cells lacking NF1 and budding yeast lacking IRA2 share the high-PKA phenotype suggests that the yeast model might be useful for targeting the cell-autonomous effects of NF1 loss in Schwann cells. The yeast platform enables rapid and cost-effective high-throughput chemical screening and allows for the use of powerful yeast genetics to identify new drug targets.

To identify therapeutic agents and target pathways for NF1-associated tumors, we performed a high-throughput chemical screen in mammalian MPNST cell lines and in the yeast. Here we describe a novel compound that preferentially inhibits both a NF1-deficient MPNST cell line and IRA2-deficient yeast. In yeast, growth inhibition is partially alleviated by high-copy expression of NAB3, which encodes an RNA-binding protein that regulates transcript termination of non-polyadenylated Pol II transcripts (18). This finding led us to a novel genetic interaction between IRA2 and NAB3, suggesting a functional interaction between Ras signaling and the non-poly(A)-dependent termination pathway which may have relevance to mammalian cells and the treatment of MPNST.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strain generation and high-copy suppressor screening

Strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. erg6Δ and erg6Δ ira2Δ were generated using standard one-step PCR-based gene deletion methods (19, 20). Strains and plasmids used for high-copy suppressor screening are described in the Supplemental Figure 2 legend. The YEp13-NAB3 plasmid was generated from a suppressing YEp13 plasmid containing genomic DNA of chromosome XVI from 183393 to 188100 by excising a NcoI-XbaI fragment and re-ligating the construct. nab3Δ nab3-3 was obtained from Dr. M. Swanson, and nab3–11 was a gift from Dr. J. Corden. nab3-ts alleles were confirmed by sequencing and introduced to the Σ1278b genetic background by backcrossing. The ctk1Δ::KANMX allele was backcrossed to the Σ1278b background from the Open Biosystems yeast deletion collection. Strains were backcrossed at least four times.

Table 1. Yeast strains used in this study.

Strains were generated as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods. All strains are mating type a, unless indicated.

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| MLY41a | ura3-52 | Lorenz, 1994 |

| MDW057 | As MLY41a erg6Δ::URA3 | This study |

| MDW035 | As MLY41a erg6 Delta;::URA3 ira2::URA3- FOAR | This study |

| MDW230 | erg6Δ::HIS3 ira2Δ::URA3-FOAR leu2-3 his3-11 ura3-52 [pMW001] | This study |

| MDW270 | As MDW230, [YEp13] 5-FOAR | This study |

| MDW528 | As MDW230, [pMW050] 5-FOAR | This study |

| YSW550-1D | leu2Δ2 ura3-52 his3 trp1-289 nab3 Delta;2::LEU2 TRP1::nab3-3 α | M. Swanson |

| YPN103 | ade2 can1-100 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 nab3-11 | J. Corden |

| MDW547 | nab3Δ::LEU2 TRP1::nab3-3 | Cross YSW550-1D to MLY four times |

| MDW548 | ira2Δ::URA3 nab3 Delta;::LEU2 TRP1::nab3-3 | Cross YPN101 to MLY four times |

| MDW551 | nab3-11 | This study |

| MDW552 | ira2Δ::URA3 nab3-11 | This study |

| MDW561 | erg6Δ::URA3 nab3 Delta;::LEU2 nab3-3 | |

| MDW578 | ctk1Δ::KANMX erg6 Delta;::URA3 | |

| Plasmid | Description | Source |

| pMW001 | pRS416-ERG6 | This study |

| pMW050 | YEp13-NAB3 | This study |

High-throughput screening

Screening was performed at the University of Cincinnati Drug Discovery Center using standard screening methodology. Full details of the screening protocol are included in the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Tissue Culture

STS26T and T265 cells were routinely maintained in DMEM high-glucose medium (Invitrogen 11965-092) with 10% FBS (Invitrogen 26140-079) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen 15070-063). The cell lines and their original sources have been described (21). Each has been certified mycoplasma-free and tested negative for a panel of mouse viruses. Their identity was validated by short tandem repeat (STR) genotyping. These cells had not previously been genotyped by this method, so there are no existing reference data. None of the genotypes match other cell lines in publicly accessible databases that have been queried. The cell lines are re-tested annually to ensure their ongoing identity. For drug sensitivity assays, 1000 cells were plated to 96-well plates in 100 μL medium. Plates were incubated for one day, then an additional 100 μL of medium containing 0.2% DMSO and twice the desired final concentration of UC1 was added to the wells (final 200 μL, 0.1% DMSO). Cells were incubated for three days, and viability was assessed by MTS assay. Three wells were analyzed for each condition, and the experiment was performed three times.

Yeast drop assays

UC1 was added to 5 mL 55° molten synthetic complete (SC) agar from DMSO working solutions, mixed, and poured to tissue culture plates (Falcon 35-3002). Plates were uncovered for 20 minutes in a fume hood. Plates were prepared immediately before use. Log phase cultures were diluted to OD600 = 0.08, 10-fold serial dilutions were carried out in Eppendorf tubes, and 5 μL of each dilution was placed onto agar. Plates were incubated at 30° or at the indicated temperatures for three days.

Yeast 96-well plate assays

Log phase cultures were diluted to OD600 = 0.05 in SC medium and 148.5 μL cell suspension was added to 96-well plates containing 1.5 μL DMSO or 1.5 μL 100X compound (1% DMSO final). Plates were gently agitated, then incubated for 18 hours at 30° in a humidified chamber. Optical densities were measured on a Molecular Devices Thermomax plate reader.

Yeast RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Triplicate log phase cultures were treated with DMSO or UC1 for 8 hours at 30° in 125 mL flasks. RNA was extracted from 5–10 × 106 cells with TriReagent (MRC TR-118) per manufacturers instruction. Full details of the extraction method are listed in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

RNA was treated with DNAse I (Roche 04716728001) according to manufacturers instructions. 200 ng of DNAse-I-treated RNA was used in a reverse transcription using Invitrogen SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen 18080-044) according to manufacturer’s instructions. 2 μL of the RT reaction was used in a traditional PCR, using primers described in (22). Cycling was performed with 94° denaturation, 50° annealing, and 72° extension for 0:45. For PYK1 reactions, samples were removed after 22 cycles. For SNR readthrough reactions, samples were removed after 30 cycles.

Results

Identification of UC1 in chemical screens

To identify molecules with selective toxicity toward NF1-deficient cells, a chemical screen was performed in MPNST lines with functional NF1 (STS26T, NF1+/+) and loss of NF1 (T265, NF1−/ −) (23, 24). We screened 6000 compounds selected for chemical diversity from 250,000 compounds available through the University of Cincinatti Drug Discovery Center (DDC). The DDC library is chemically diverse and broadly represents the molecular space of drug-like compounds. The library is designed to remove non-drug-like molecules with unfavorable characteristics such as high reactivity, chemical instability, low solubility, and poor Lipinski profiles, thus maximizing the probability of finding a biologically relevant screening hit. Compounds showing greater inhibition against T265 than STS26T at 10 μM were selected for follow-up. Hits were confirmed in triplicate and tested in a 10-point dose response assay to define AC50 values in both lines.

In parallel, compounds were screened in congenic budding yeast strains, one with deletion of IRA2 (ira2Δ) and one with an intact (wild-type) IRA2. Both strains had deletion of ERG6 (erg6Δ), which increases cell permeability (25–29). We confirmed ira2Δ phenotypes including sensitivity to oxidative stress and failure to accumulate glycogen. Compounds were tested in both strains at ~20μM and confirmed hits having a greater inhibitory effect on erg6Δ ira2Δ than on erg6Δ were tested in a dose-response assay to define AC50 values. We identified a set of compounds that inhibited both the T265 cell line and the ira2Δ budding yeast.

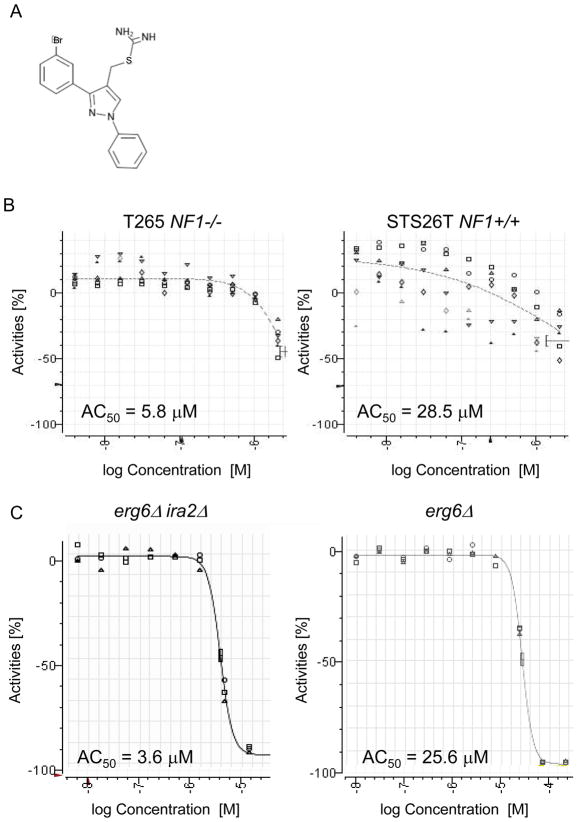

One compound, [3-(3-bromophenyl)-1-phenylpyrazol-4-yl]methyl carbamimidothioate hydrochloride, which we have named UC1 (Figure 1A), was selected for follow-up based on its promising activity and commercial availability. In the cell line screen, UC1 had a greater activity against NF1−/ − T265 cells than the NF1+/+ STS26T cells (Figure 1B). T265 cells were inhibited with an AC50 of 5.8 μM while STS26T cells were inhibited with an AC50 of 28.5 μM. In the yeast screen, UC1 inhibited an erg6Δ ira2Δ strain at an AC50 of 3.6 μM, while the control erg6Δ IRA2 strain was inhibited at 25.6 μM (Figure 1C). An identical compound lacking the meta bromine showed reduced activity in erg6Δ ira2Δ cells, with an AC50 value of 42.2 μM ± 1.6 μM (mean ± SD) (Supplemental Figure 1). This suggests that the meta bromine is essential for the UC1 compound activity and shows that the yeast platform can be used to evaluate structure-activity relationships.

Figure 1. High-throughput screening results for UC1.

(A) Chemical structure of the UC1 molecule. (B) UC1 activity in high-throughput screening of MPNST cell lines with differing NF1 status. Dose-response curves for T265 (Left) and STS26T (Right) are shown. The X-axis represent the log of the UC1 concentration while the Y-axis represents the percent growth relative to control. (C) Dose-response curves for UC1 in budding yeast high-throughput screen. Dose-response curves are shown for erg6Δ ira2Δ (Left) and erg6Δ (Right), with X- and Y- axes as described in (B).

Confirmation of UC1 activity

UC1 activity was confirmed in the laboratory, using compound from an outside supplier (ChemBridge) to exclude possible effects of prolonged storage on the compound. UC1 decreased the number of viable T265 cells by MTS assay with an AC50 of 3.35 μM (95% CI 2.41 to 4.29 μM) (Figure 2A). In contrast, STS26T had a significant fraction of viable cells even at the highest dose tested (10 μM), indicating a minimum 3-fold selectivity for the NF1−/ − cell line and confirming the differential sensitivity seen found in the screen. We tested MPNST-724, a non-NF1-associated MPNST cell line which retains neurofibromin protein expression (30, 31). This line did not have dose-dependent growth inhibition up to 10 μM UC1, suggesting that MPNST cells with functioning NF1 are not effectively targeted by UC1. To determine if UC1 was toxic toward non-MPNST cells, we tested a sarcoma cell line, HT1080, which was inhibited with an AC50 of 9.02 μM (data not shown).

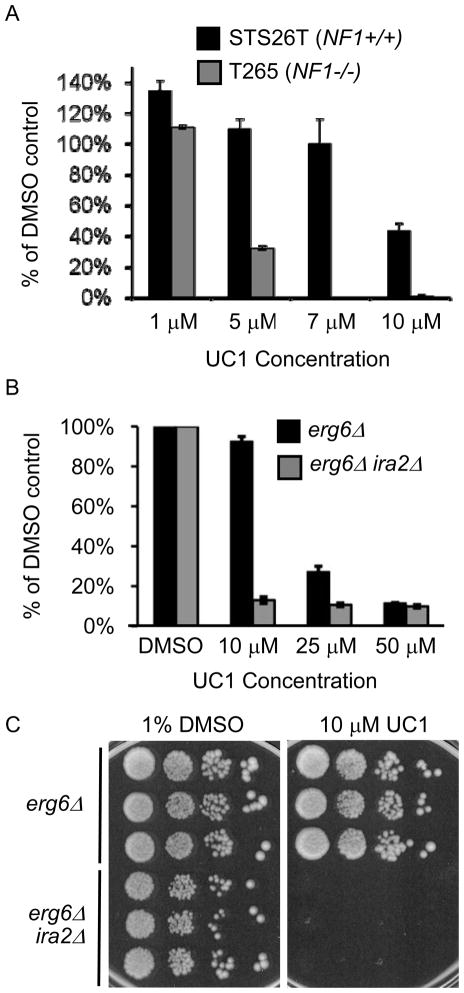

Figure 2. Confirmation of UC1 activity in yeast and cell lines.

(A) Growth of STS26T and T265 cell lines in the presence of UC1. Values from MTS assay were normalized to control treated samples and represent the mean +/− standard deviation of three independent assays. (B) A 96-well plate assay was performed on erg6Δ and erg6Δ ira2Δ strains. Values are OD600 normalized to DMSO-treated control wells an represent mean +/− standard deviation of three wells per condition after 18 hours of growth. (C) Agar based activity of UC1. A drop assay was performed on agar containing UC1. Plates were incubated for three days at 30° before photographing. Three independent cultures of each strain were tested.

In yeast, IRA2 deletion in a erg6Δ strain increased sensitivity to UC1 in a 96-well plate growth assay (Figure 2B), and 10 μM UC1 completely inhibited the growth of an erg6Δ ira2Δ strain on agar medium (Figure 2C). Increased permeability and loss of IRA2 are necessary for UC1 activity, because ERG6 IRA2 and ERG6 ira2Δ strains were not inhibited by UC1 (data not shown). These results confirmed the findings from the high-throughput screens and indicated that UC1 preferentially targets NF1 and IRA2 deficient cells.

Increasing levels of Nab3 suppresses UC1 sensitivity

We used a high-copy suppressor approach in yeast to identify potential targets for UC1. A UC1-sensitive strain was transformed with a high-copy plasmid library bearing fragments of the yeast genome and resistant colonies were isolated. High-copy suppressor screening required high-efficiency transformation of drug-sensitive cells. Although erg6Δ strains have been used in high-throughput screens, their utility in target identification studies is limited because of low transformation efficiency (29). To circumvent this issue, a plasmid shuffle approach was employed (Supplemental Figure 2). An erg6Δ ira2Δ strain bearing a rescue plasmid encoding ERG6 was transformed with a high-copy library. The rescue plasmid was then counter-selected, and 25,000 library transformants were plated onto 10 μM UC1 agar medium. Resistant colonies were selected for follow-up. To identify constructs that were most informative for the UC1 mechanism, phenotypic assays were used to eliminate nonspecific suppressors: cells which regained the ERG6 gene, restored PKA regulation, or were cross-resistant to a structurally unrelated compound (Supplemental Figure 3). Plasmid DNA was isolated, shuttled, and unique constructs were identified by restriction digest. The genome regions and associated reading frames identified by DNA sequencing are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. High-copy suppressors of UC1 sensitivity.

Constructs were isolated from UC1-resistant colonies as described in the text and in Materials and Methods. Constructs were identified by DNA sequencing.

| No resistance to unrelated compound | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr. | Start | End | # Isolated | Full-length ORFs |

| XV | 1032412 | 1037214 | 1 | NDD1 |

| XII | 1000673 | 1007148 | 1 | IMD3, CNA1, TSR2 |

| XIII | 350140 | 355586 | 1 | YET2, ARA2, ARG80, MCM1 |

| XVI | 183393 | 188100 | 1 | NAB3, YPL191C |

| Slightly resistant to unrelated compound | ||||

| Chr. | Start | End | # Isolated | Full-length ORFs |

| XIII | 913156 | Ty element | 1 | Unknown |

| XV | 380485 | 389109 | 2 | BUB3, STI1, CIN5, DFG16, |

| XV | 1032412 | 1037214 | 3 | NDD1 |

| VII | 954571 | 961868 | 4 | YHB1, PHO81, NAS6 |

| XIII | 423056 | 433459 | 2 | SEC14, NAM7, ISF1 |

| XV | 836614 | 849743 | 1 | HEM4 |

| VII | 957743 | 961496 | 1 | YHB1 |

| IX | 166131 | 175721 | 1 | MOB1, SLM1, SHQ1, DPH1, XBP1 |

| XV | 1032413 | 1037214 | 1 | NDD1 |

| VII | 260828 | 265887 | 1 | ITC1, SNT2 |

| Highly resistant to unrelated compound | ||||

| Chr. | Start | End | # Isolated | Full-length ORFs |

| XIII | 250991 | 256880 | 1 | MRPL39, ERG6, YAP1, GIS4 |

| XVI | 24342 | Ty element | 3 | Unknown |

| XIII | 556382 | 561831 | 7 | TIF34 |

| XV | 840150 | 845510 | 3 | HEM4, CAF20, RFM1 |

| XIII | 251832 | 256880 | 2 | ERG6, YAP1 |

| XIII | 555224 | 561831 | 2 | TIF34 |

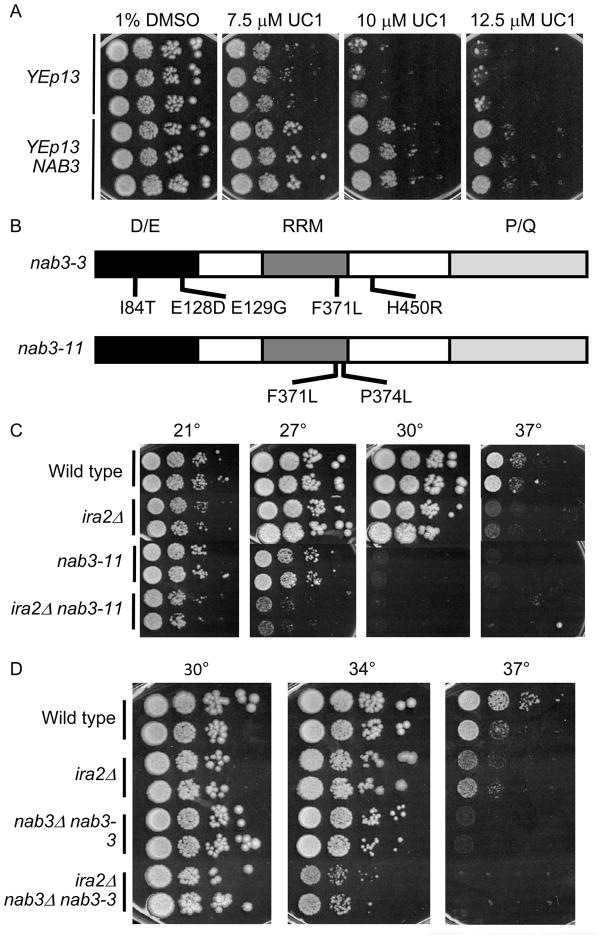

Suppressor constructs were re-transformed into the parental strain for confirmation of UC1 resistance and sensitivity to the structurally unrelated compound. The most specific suppressor construct contained a region of yeast chromosome XVI containing two complete open reading frames, NAB3 and YPL191C. Subcloning revealed that NAB3 was responsible for UC1 sensitivity suppression. The resistance conferred by NAB3 overexpression was easily appreciated on agar (Figure 3A). NAB3 encodes a single-stranded RNA binding protein that interacts with partners Nrd1 and Sen1, forming a complex that associates with the RNA Pol II C-terminal domain (18, 32, 33). The complex directs termination and processing of small nuclear and nucleolar RNA transcripts (snRNA/snoRNA) and termination and degradation of antisense, intergenic, and select messenger RNA (34–36).

Figure 3. NAB3 suppresses UC1 sensitivity and interacts genetically with ira2Δ.

(A) A drop assay on synthetic complete medium was performed with increasing doses of UC1 on three independent cultures of erg6Δira2Δcontaining the empty vector YEp13 or the vector plus a fragment containing NAB3. Plates were incubated for three days at 30°before photographing. (B) nab3-ts alleles analyzed with IRA2 deletion. D/E represents a N-terminal acidic domain, RRM represents the RNA recognition motif, and P/Q represents a C-terminal proline/glutamine rich domain. (C-D) Σ1278b background strains were analyzed in drop assays at the indicated temperatures after three days of growth on synthetic complete medium. Two strains of each genotype were analyzed.

IRA2 and NAB3 interact genetically

One explanation for NAB3 overexpression suppressing UC1 sensitivity is that UC1 is targeting Nab3 and compromising its function. In this model, NAB3 overexpression confers resistance by increasing the quantity of Nab3 protein, so that higher concentrations of UC1 are required for inactivation. This predicted that deletion of NAB3 would be synthetically lethal with IRA2 deletion. At the time of our studies, no such interaction had been reported. NAB3 is essential, so temperature sensitive (ts) alleles of NAB3 were used to test for a genetic interaction. A synthetic lethal effect between ira2Δ and a nab3-ts strain is indicated by lack of growth of ira2Δ nab3-ts double mutants at a temperature that permits growth of the single mutants. Two nab3-ts alleles were introduced to Σ1278b strains wild-type or null for IRA2 (Figure 3B, adapted from (33)). Both alleles showed a negative genetic interaction with ira2Δ. Strains with a nab3-11 allele grew at 27° and failed at 30°, while an ira2Δ nab3-11 strains grew poorly at 27° (Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained with nab3-3. While nab3-3 strains grew at 34°, ira2Δ nab3-3 strains grew poorly at this temperature (Figure 3D). This evidence showed that an ira2Δ strain is more sensitive to Nab3 dysfunction than an IRA2 strain. Our discovery is consistent with a recent report of genetic interactions between the Ras-PKA pathway and Nab3-Nrd1 (M. M. Darby, X. Pan, L. Serebreni, J. D. Boeke, and J. L. Corden, submitted for publication).

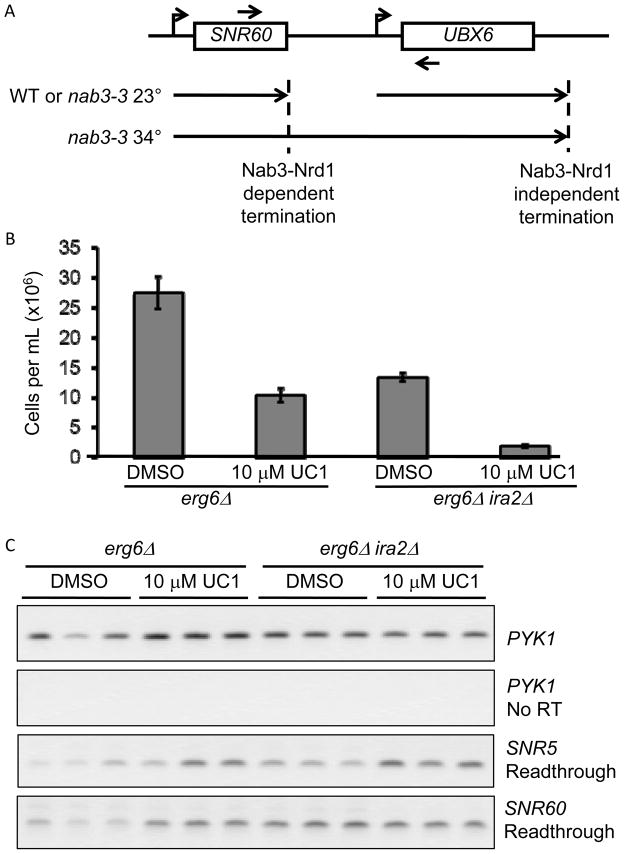

UC1 does not inhibit the role of Nab3 in transcript termination

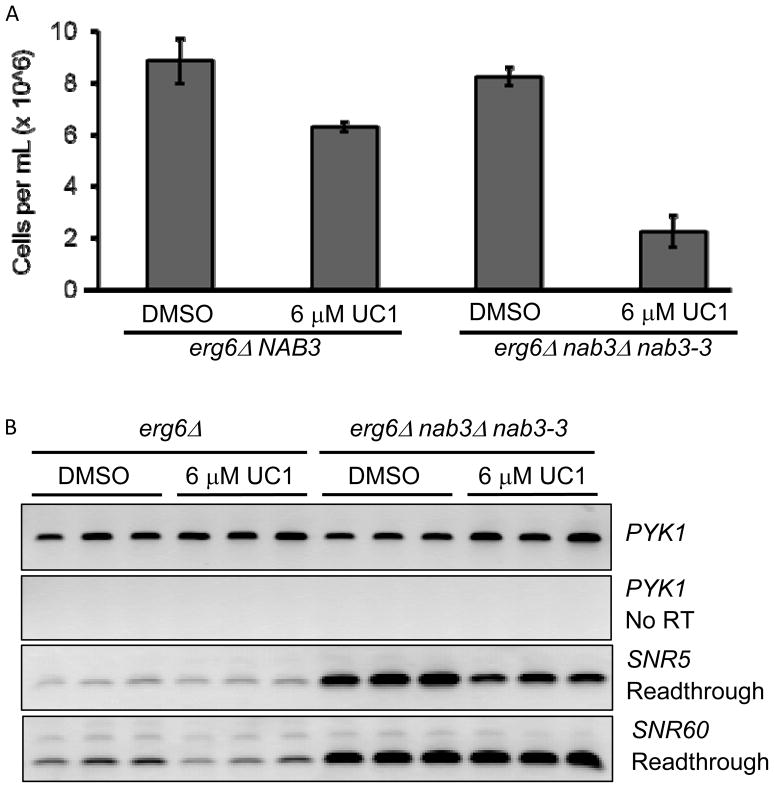

A genetic interaction supported the possibility of Nab3 as a target in IRA2-deficient yeast. To determine if UC1 was acting directly to inhibit Nab3, a readthrough transcription assay was performed. Inactivation of Nab3 or Nrd1 generates extended transcription products downstream of snoRNAs which can be detected by RT-PCR with primers depicted in Figure 4A (adapted from (22)). We validated this detection approach using the nab3-ts strain generated from earlier experiments (data not shown, and Figure 5). erg6Δ and erg6Δ ira2Δ cultures were treated with vehicle or 10 μM UC1 for 8 hours and analyzed for readthrough transcription by RT-PCR. This treatment inhibited the growth of erg6Δ ira2Δ by 86% and that of erg6Δ strain by 62% (Figure 4B). Despite inhibition in both strains, no increase in readthrough transcription at either of two small nucleolar RNA loci was detected (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Nab3 inactivation confers UC1 sensitivity.

(A) Schematic of readthrough detection. See text for details. (B) Triplicate cultures of erg6Δ and erg6Δ ira2Δ were treated with DMSO or UC1 for 8 hours. Strain growth was monitored by OD600 and converted to cells per mL. Values are the mean +/− standard deviation of three cultures. (C) RT-PCR detection of readthrough transcripts in nab3-3 and UC1-treated samples. Samples from cells treated in (B) were processed for RNA extraction and RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. The presence of product indicates readthrough transcription at the SNR locus.

Figure 5. UC1 inhibits cell growth without increasing readthrough.

(A)Growth of erg6Δ and erg6Δ nab3-3 strains treated with UC1 for 8 hours. Cell density in triplicate cultures was determined by OD600 as in Figure 4. (B) RT-PCR for SNR termination defects were performed as described in materials and methods and in Figure 4.

Dysfunctional Nab3-Nrd1 leads to markedly increased NRD1 mRNA levels by alleviating negative feedback on NRD1 expression, providing a sensitive assay for detecting Nab3-Nrd1 complex activity (34). We did not detect significant increases in NRD1 mRNA levels in samples from UC1-treated cultures by real-time RT-PCR (data not shown). Along with the lack of readthrough transcription, this result indicated that UC1 is not likely to have a direct inhibitory effect on Nab3-Nrd1-dependent termination.

Functional homologues of Nab3 and Nrd1 have not yet been identified in mammals. However, Nrd1 bears structural resemblance to the SCAF4 and SCAF8 C-terminal associated splicing factors, while Nab3 is similar to HNRNPC, a RNA binding protein. HNRNPC was identified in a siRNA screen to identify targets in cells with activating point mutations in Ras, suggesting that HNRNPC may be a target in Ras-deregulated cells (37). In preliminary assays, knockdown of HNRNPC or SCAF8 by shRNA inhibited STS26T and T265 cell lines equally (data not shown). Because knockdown of these factors was not selectively toxic toward the NF1 deficient cell line, we concluded that neither factor is likely to be the molecular target of UC1 in mammalian cells.

Nab3 inactivation confers UC1 sensitivity

Our data established that UC1 sensitivity is suppressed by overexpression of NAB3. However, assays in erg6Δ and erg6Δ ira2Δ cells showed that UC1 did not disrupt Nab3-dependent termination. We considered that UC1 sensitivity could result from Ras activity downregulating Nab3. This would explain the ira2Δ/nab3-ts genetic interaction; if high Ras activity due to ira2Δ compromised an essential Nab3 activity, cells would be more sensitive to further disruption of a specific activity of Nab3 by UC1. This model predicted that drug-permeable IRA2 cells with Nab3 dysfunction would be UC1-sensitive. Therefore, we tested the UC1 sensitivity of an erg6Δ nab3-3 strain at a semi-permissive temperature. Under these conditions, 6 μM UC1 inhibited the erg6Δ control strain by 28% after 8 hours, while the erg6Δ nab3-3 strain was inhibited by 73% (Figure 5A). The nab3-ts strain showed noticeably increased readthrough transcription. Consistent with our previous data, UC1 treatment did not increase readthrough in either strain (Figure 5B). This indicated that downregulation of Nab3 activity leads to increased UC1 sensitivity in the setting of normal Ras signaling. IRA2 deletion did not lead to readthrough transcription (Figure 4C, compare DMSO samples for erg6Δ and erg6Δ ira2Δ), indicating that Ras activation may be modifying a specific function of Nab3, rather than globally deregulating Nab3-dependent termination.

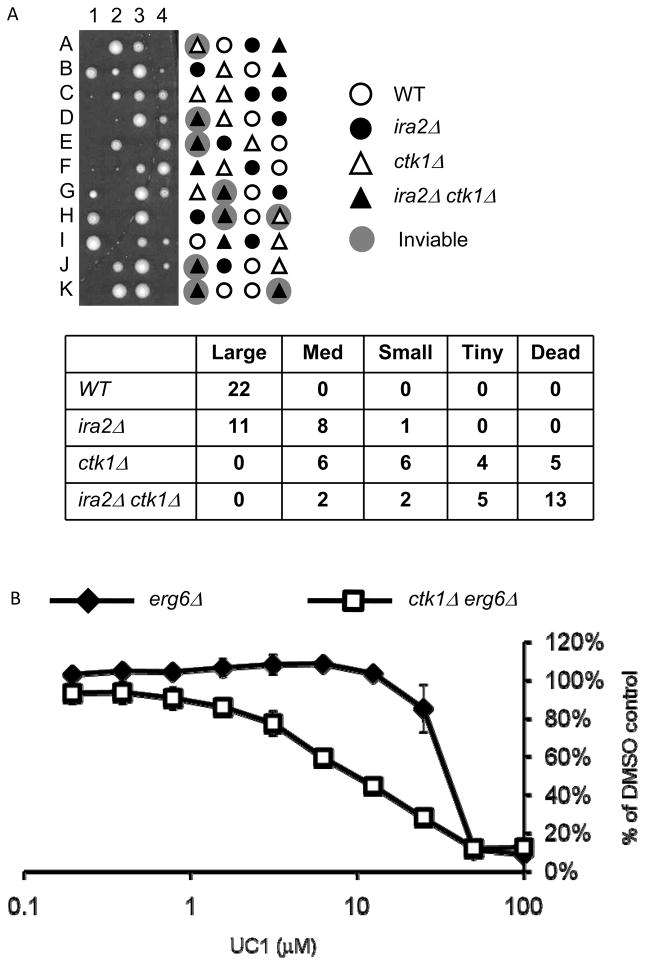

ctk1Δconfers UC1 sensitivity and interacts genetically with ira2Δ

The Nab3/Nrd1 complex acts in association with the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA Pol-II. This association is partly regulated by the yeast CTD kinase Ctk1, which phosphorylates the CTD and opposes the association of Nab3/Nrd1 with the Pol II holoenzyme (33, 38, 39). ctk1Δ rescues the temperature sensitivity of a nrd1-ts allele by altering the CTD phosphorylation state and promoting Nab3-Nrd1 association (33). We questioned whether UC1 could be interfering with Nab3 recruitment to the CTD, which could compromise other functions of Nab3 in addition to non-poly(A) transcript termination. This model predicted that CTK1 deletion would rescue UC1 sensitivity by promoting the Nab3-CTD interaction. In generating strains to test this model, we observed synthetic lethality between ctk1Δ and ira2Δ In tetrad analpysis, ctk1Δ spores were viable, while the double mutant ctk1Δ ira2Δ spores formed minute colonies (Figure 6A). This result was unsurprising, as CTK1 deletion as well as other mutations that interfere with the Pol II CTD are synthetically lethal with Ras activation (40–42).

Figure 6. ctk1Δ interacts genetically with ira2Δ and sensitizes erg6Δ cells to UC1.

(A) A diploid ira2Δ::URA3/IRA2 ctk1Δ::KANMX/CTK1 was sporulated and dissected to YPD agar. Plates were grown for three days at 30°. Colony size was scored, then genotypes were determined by stamping to C-Ura and G418 medium. Because of genetic markers, ira2Δ colonies grow on C-Ura while ctk1Δ colonies grow on G418 allowing full identification of the genotype for each colony. (B) Three cultures of erg6Δand erg6Δira2Δwere treated with UC1 in a 96-well plate dose-response assay. Growth after 18 hours of incubation is expressed as % of DMSO control OD595. Values are mean +/− standard deviation of three cultures.

Because of the ira2Δ/ctk1Δ negative genetic interaction, we tested for a ctk1Δ/UC1 interaction in an erg6Δ IRA2 background. In contrast to our original prediction, an erg6Δ ctk1Δ strain was more sensitive to UC1 than erg6Δ (Figure 6B). This unexpected result indicated that CTK1 deletion is sufficient to increase UC1 sensitivity. Thus, three different genetic modifications that are linked to Pol II CTD function–ira2Δ, ctk1Δ, and nab3-ts – all conferred UC1 sensitivity, suggesting that UC1 is impinging on Pol II activity. The mechanism of impingement, including the receptor for UC1 and whether this is a conserved target, is an avenue of future investigation.

Discussion

This work illustrates the power of integrating mammalian and model systems to identify new compounds and explore therapeutic targets for cancer treatment. We used human cell line and budding yeast chemical screens to identify candidate compounds for the treatment of tumors associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. While this work was underway, the MPNST cell lines that we employed in our study were used to characterize other small molecules targeting NF1 loss (43). We identified UC1, a compound targeting NF1-deficient mammalian cells and budding yeast lacking the NF1 homologue IRA2. We employed yeast genetic approaches to identify a genetic suppressor of UC1 sensitivity. This led to the discovery of a genetic interaction between the Ras signaling pathway and the machinery that regulates transcript termination, a finding that has been confirmed by independent studies (M. M. Darby, X. Pan, L. Serebreni, J. D. Boeke, and J. L. Corden, submitted for publication). This approach identified a candidate small molecule for pharmacologic development, as well as a potential novel target pathways for treating NF1-associated tumors.

Identification of UC1 and cross-species validation

While differential sensitivity of UC1 in the MPNST cell lines may be caused by NF1 loss, these cell lines are not isogenic and other genetic differences could be responsible for differential sensitivity. UC1 activity in IRA2-deficient budding yeast is significant because the yeast strains employed – erg6Δ IRA2 modeling an NF1+/+ cell and erg6Δ ira2Δ modeling an NF1−/ − cell – are derived from the same parental strain and are congenic. Consequently differential activity in budding yeast cells strongly suggests that UC1 is targeting the ira2Δ phenotype, a model of NF1−/ − status in mammalian cells.

NAB3 expression suppresses UC1 sensitivity

The yeast system can be used to identify the potential mechanism of action of new compounds. We identified NAB3 as a high-copy suppressor of UC1 sensitivity and found that Ras deregulation renders cells more sensitive to Nab3 inactivation. Since NAB3 is an essential gene, it is often not included in high-throughput genetic screens, which may explain why this interaction has not been uncovered previously (44). It was previously noted that mutations in the yeast adenylate cyclase CYR1 rescue the temperature sensitive defect of a nrd1 temperature sensitive strain (33).

Evidence against direct inhibition of Nab3 by UC1

With Nab3 or Nrd1 inactivation, transcription termination at small nuclear and nucleolar RNA is compromised, resulting in readthrough transcription (18). We did not find evidence for readthrough in UC1-treated cells, suggesting that UC1 does not cause a non-poly(A)-dependent termination defect. This might indicate that UC1 is not targeting Nab3. However, lethality in NAB3 mutants might be due to deregulation of a subset of essential genes, and we cannot rule out the possibility that UC1 causes termination defects at specific loci. Alternatively, UC1 might inhibit an essential function of Nab3 that is unrelated to termination. Two research groups have implicated Nab3/Nrd1 in silencing Pol II transcription at the rRNA encoding DNA (rDNA) array (45, 46). UC1 might modify Nab3 activity at rDNA, but not at other termination sites in the genome.

Other potential mammalian homologues of Nab3-Nrd1

The Nab3/Nrd1 complex can limit expression of certain genes bearing Nab3/Nrd1 termination motifs in the 5′ coding region (34). Therefore, Nab3/Nrd1 limits Pol II activity in a gene-specific manner. In mammalian cells, the Negative Elongation Factor (NELF) and DRB Sensitivity Inducing Factor (DSIF) negatively regulate Pol II. These factors are opposed by P-TEFb, the mammalian homologue of yeast Ctk1. It has been proposed that the Nab3/Nrd1 complex in yeast plays a similar role in transcription as NELF/DSIF in mammals (33). Synthetic lethality between IRA2 and CTK1 deletion suggests that targeting Cdk9, the kinase component of pTEFb and the mammalian homologue of Ctk1, could be a therapeutic strategy for MPNST.

Conclusion

We identified two genetic interactions in yeast that suggest target pathways for NF1-associated malignancy; first, the functional homologue of Nab3 and second, the functional homologue of Ctk1. This work shows that yeast model systems can identify lead compounds for development in the treatment of human cancer. We have developed an approach for genetic suppressor screening in the erg6Δ background, which previously limited the application of yeast-based chemical screens. Genetic approaches in yeast can be used to identify potential target pathways for novel compounds. The cell lines used in this work are suitable for xenograft assays, allowing for future investigation of UC1 activity in an in vivo model (47, 48). This technology may be applied to synthetic lethality screening for other conserved tumor suppressor genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by Prouty Norris Cotton Cancer Center Funds (YS) and NIH/NINDS R21NS060940 to YS and NR, NIH training grant T32-CA009658-18 YS, and by a Children’s Tumor Foundation Young Investigator Award to MDW. MDW is an Albert J. Ryan fellow.

We thank members of the Sanchez Laboratory for their comments. We thank Dr. Craig Tomlinson and Heidi Traskof the Dartmouth Genomics and Microarray Facility. We thank Dr. Jeffrey Corden and Miranda Darby of Johns Hopkins University for analysis of real-time RT-PCR data and for sharing unpublished results.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Korf BR. Malignancy in neurofibromatosis type 1. The oncologist. 2000;5:477–85. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-6-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll SL, Ratner N. How does the Schwann cell lineage form tumors in NF1? Glia. 2008;56:1590–605. doi: 10.1002/glia.20776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferner RE, Gutmann DH. International consensus statement on malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis. Cancer research. 2002;62:1573–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans DG, Baser ME, McGaughran J, Sharif S, Howard E, Moran A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis 1. Journal of medical genetics. 2002;39:311–4. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.5.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGaughran JM, Harris DI, Donnai D, Teare D, MacLeod R, Westerbeek R, et al. A clinical study of type 1 neurofibromatosis in north west England. Journal of medical genetics. 1999;36:197–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter DE, Prasad V, Foster L, Dall GF, Birch R, Grimer RJ. Survival in Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumours: A Comparison between Sporadic and Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Tumours. Sarcoma. 2009;2009:756395. doi: 10.1155/2009/756395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutkowski JL, Wu K, Gutmann DH, Boyer PJ, Legius E. Genetic and cellular defects contributing to benign tumor formation in neurofibromatosis type 1. Human molecular genetics. 2000;9:1059–66. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.7.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Y, Ghosh P, Charnay P, Burns DK, Parada LF. Neurofibromas in NF1: Schwann cell origin and role of tumor environment. Science (New York, NY) 2002;296:920–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1068452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, Williams JP, Rizvi TA, Kordich JJ, Witte D, Meijer D, et al. Plexiform and dermal neurofibromas and pigmentation are caused by Nf1 loss in desert hedgehog-expressing cells. Cancer cell. 2008;13:105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng H, Chang L, Patel N, Yang J, Lowe L, Burns DK, et al. Induction of abnormal proliferation by nonmyelinating schwann cells triggers neurofibroma formation. Cancer cell. 2008;13:117–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang FC, Ingram DA, Chen S, Zhu Y, Yuan J, Li X, et al. Nf1-dependent tumors require a microenvironment containing Nf1+/− − and c-kit-dependent bone marrow. Cell. 2008;135:437–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monk KR, Wu J, Williams JP, Finney BA, Fitzgerald ME, Filippi MD, et al. Mast cells can contribute to axon-glial dissociation and fibrosis in peripheral nerve. Neuron glia biology. 2007;3:233–44. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X08000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka K, Nakafuku M, Satoh T, Marshall MS, Gibbs JB, Matsumoto K, et al. S. cerevisiae genes IRA1 and IRA2 encode proteins that may be functionally equivalent to mammalian ras GTPase activating protein. Cell. 1990;60:803–7. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90094-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosch HU, Roberts RL, Fink GR. Ras2 signals via the Cdc42/Ste20/mitogen-activated protein kinase module to induce filamentous growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:5352–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toda T, Uno I, Ishikawa T, Powers S, Kataoka T, Broek D, et al. In yeast, RAS proteins are controlling elements of adenylate cyclase. Cell. 1985;40:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HA, Ratner N, Roberts TM, Stiles CD. Schwann cell proliferative responses to cAMP and Nf1 are mediated by cyclin D1. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1110–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01110.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Y, Chiamvimonvat N, Vazquez AE, Akunuru S, Ratner N, Yamoah EN. Gene-targeted deletion of neurofibromin enhances the expression of a transient outward K+ current in Schwann cells: a protein kinase A-mediated mechanism. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9194–202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09194.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinmetz EJ, Conrad NK, Brow DA, Corden JL. RNA-binding protein Nrd1 directs poly(A)-independent 3′-end formation of RNA polymerase II transcripts. Nature. 2001;413:327–31. doi: 10.1038/35095090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boeke JD, Trueheart J, Natsoulis G, Fink GR. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods in enzymology. 1987;154:164–75. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longtine MS, McKenzie A, 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast (Chichester, England) 1998;14:953–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller SJ, Rangwala F, Williams J, Ackerman P, Kong S, Jegga AG, et al. Large-scale molecular comparison of human schwann cells to malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor cell lines and tissues. Cancer research. 2006;66:2584–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh N, Ma Z, Gemmill T, Wu X, Defiglio H, Rossettini A, et al. The Ess1 prolyl isomerase is required for transcription termination of small noncoding RNAs via the Nrd1 pathway. Molecular cell. 2009;36:255–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badache A, De Vries GH. Neurofibrosarcoma-derived Schwann cells overexpress platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptors and are induced to proliferate by PDGF BB. Journal of cellular physiology. 1998;177:334–42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199811)177:2<334::AID-JCP15>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahlberg WK, Little JB, Fletcher JA, Suit HD, Okunieff P. Radiosensitivity in vitro of human soft tissue sarcoma cell lines and skin fibroblasts derived from the same patients. International journal of radiation biology. 1993;63:191–8. doi: 10.1080/09553009314550251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunstan HM, Ludlow C, Goehle S, Cronk M, Szankasi P, Evans DR, et al. Cell-based assays for identification of novel double-strand break-inducing agents. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94:88–94. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.2.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham TR, Scott PA, Emr SD. Brefeldin A reversibly blocks early but not late protein transport steps in the yeast secretory pathway. The EMBO journal. 1993;12:869–77. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee DH, Goldberg AL. Selective inhibitors of the proteasome-dependent and vacuolar pathways of protein degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:27280–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abe F, Hiraki T. Mechanistic role of ergosterol in membrane rigidity and cycloheximide resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1788:743–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaber RF, Copple DM, Kennedy BK, Vidal M, Bard M. The yeast gene ERG6 is required for normal membrane function but is not essential for biosynthesis of the cell-cycle-sparking sterol. Molecular and cellular biology. 1989;9:3447–56. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez G, Torres K, Liu J, Hernandez B, Young E, Belousov R, et al. Autophagic survival in resistance to histone deacetylase inhibitors: novel strategies to treat malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Cancer research. 2011;71:185–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian S, Thayanithy V, West RB, Lee CH, Beck AH, Zhu S, et al. Genome-wide transcriptome analyses reveal p53 inactivation mediated loss of miR-34a expression in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. The Journal of pathology. 2010;220:58–70. doi: 10.1002/path.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carroll KL, Pradhan DA, Granek JA, Clarke ND, Corden JL. Identification of cis elements directing termination of yeast nonpolyadenylated snoRNA transcripts. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:6241–52. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6241-6252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conrad NK, Wilson SM, Steinmetz EJ, Patturajan M, Brow DA, Swanson MS, et al. A yeast heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex associated with RNA polymerase II. Genetics. 2000;154:557–71. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arigo JT, Carroll KL, Ames JM, Corden JL. Regulation of yeast NRD1 expression by premature transcription termination. Molecular cell. 2006;21:641–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arigo JT, Eyler DE, Carroll KL, Corden JL. Termination of cryptic unstable transcripts is directed by yeast RNA-binding proteins Nrd1 and Nab3. Molecular cell. 2006;23:841–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiebaut M, Kisseleva-Romanova E, Rougemaille M, Boulay J, Libri D. Transcription termination and nuclear degradation of cryptic unstable transcripts: a role for the nrd1-nab3 pathway in genome surveillance. Molecular cell. 2006;23:853–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo J, Emanuele MJ, Li D, Creighton CJ, Schlabach MR, Westbrook TF, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies multiple synthetic lethal interactions with the Ras oncogene. Cell. 2009;137:835–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gudipati RK, Villa T, Boulay J, Libri D. Phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain dictates transcription termination choice. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2008;15:786–94. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vasiljeva L, Kim M, Mutschler H, Buratowski S, Meinhart A. The Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 termination complex interacts with the Ser5-phosphorylated RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2008;15:795–804. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howard SC, Hester A, Herman PK. The Ras/PKA signaling pathway may control RNA polymerase II elongation via the Spt4p/Spt5p complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2003;165:1059–70. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard SC, Budovskaya YV, Chang YW, Herman PK. The C-terminal domain of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II is required for stationary phase entry and functionally interacts with the Ras/PKA signaling pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:19488–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howard SC, Chang YW, Budovskaya YV, Herman PK. The Ras/PKA signaling pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae exhibits a functional interaction with the Sin4p complex of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Genetics. 2001;159:77–89. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turbyville TJ, Gursel DB, Tuskan RG, Walrath JC, Lipschultz CA, Lockett SJ, et al. Schweinfurthin A selectively inhibits proliferation and Rho signaling in glioma and neurofibromatosis type 1 tumor cells in a NF1-GRD-dependent manner. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2010;9:1234–43. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Bellay J, Kim Y, Spear ED, Sevier CS, et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science (New York, NY) 2010;327:425–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vasiljeva L, Buratowski S. Nrd1 interacts with the nuclear exosome for 3′ processing of RNA polymerase II transcripts. Molecular cell. 2006;21:239–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Houseley J, Kotovic K, El Hage A, Tollervey D. Trf4 targets ncRNAs from telomeric and rDNA spacer regions and functions in rDNA copy number control. The EMBO journal. 2007;26:4996–5006. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johansson G, Mahller YY, Collins MH, Kim MO, Nobukuni T, Perentesis J, et al. Effective in vivo targeting of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2008;7:1237–45. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahller YY, Vaikunth SS, Ripberger MC, Baird WH, Saeki Y, Cancelas JA, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 via oncolytic herpesvirus inhibits tumor growth and vascular progenitors. Cancer research. 2008;68:1170–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.