Abstract

The epidemiological and pathogenic relationship between Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis, the two causes of whooping cough (pertussis), is unclear. We hypothesized that B. pertussis, due to its immunosuppressive activities, might enhance B. parapertussis infection when the two species were present in a co-infection of the respiratory tract. The dynamics of this relationship were examined using the mouse intranasal inoculation model. Infection of the mouse respiratory tract by B. parapertussis was not only enhanced by the presence of B. pertussis, but B. parapertussis significantly outcompeted B. pertussis in this model. Staggered inoculation of the two organisms revealed that the advantage for B. parapertussis is established at an early stage of infection. Co-administration of PT enhanced B. parapertussis single infection but had no effect upon mixed infections. Mixed infection with a PT-deficient B. pertussis strain did not enhance B. parapertussis infection. Interestingly, depletion of airway macrophages reversed the competitive relationship between these two organisms, but depletion of neutrophils had no effect upon mixed infection or B. parapertussis infection. We conclude that B. pertussis, through the action of PT, can enhance a B. parapertussis infection, possibly by an inhibitory effect on innate immunity.

Keywords: Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis, pertussis toxin, mixed infection, respiratory infection

Introduction

The acute respiratory disease whooping cough (or pertussis) is caused by the gram-negative coccobacillus Bordetella pertussis, which binds to ciliated cells of the respiratory tract. However a shorter and milder form of the disease is also caused by Bordetella parapertussis (Heininger et al. 1994). Data suggest that B. parapertussis is the causative agent of a significant proportion of whooping cough cases in some global locations, including several European countries (Watanabe and Nagai 2004). In a clinical setting it is hard to distinguish between these two pathogens, and involves costly laboratory tests such as PCR assays (Tatti et al. 2008). Treatment of infection is the same regardless of which of these two species of Bordetella is the infective agent, and therefore tests to identify the causative pathogen are not always conducted. Mixed outbreaks and co-infection of patients with these two organisms have also been seen in clinical studies (Iwata et al. 1991, Mertsola 1985), and there is little understanding of the epidemiological and pathogenic relationship between the two. Both of these pathogens are restricted to human hosts, although a distinct group of B. parapertussis strains that evolved independently (B. parapertussisov) infect sheep, causing a chronic non-progressive pneumonia (Diavatopoulos et al. 2005, Porter et al. 1994). B. pertussis and B. parapertussis are believed to have evolved independently from a B. bronchiseptica-like ancestor with subsequent substantial gene loss and inactivation, and adaptation to a specific host (Diavatopoulos et al. 2005, Musser et al. 1986, Parkhill et al. 2003).

Despite evolving independently, these pathogens share a number of virulence factors including filamentous haemagglutinin (FHA), pertactin, adenylate cyclase toxin and tracheal cytotoxin (Mattoo and Cherry 2005). However B. pertussis is unique amongst the Bordetellae in that it produces the virulence factor pertussis toxin (PT), an AB5 toxin of 105 kDa in size. The enzymatically active A subunit, also referred to as S1, is an ADP ribosyltransferase which modifies heterotrimeric Gi proteins of mammalian cells, leading to inhibitory effects upon G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathways (Katada et al. 1983, Moss et al. 1983). The B-oligomer is organized into a pentameric ring structure made up of subunits S2, S3, two S4 and S5, which binds to unknown glycoconjugate receptors on the surface of the host cell, allowing internalization by endocytosis (Witvliet et al. 1989). B. parapertussis also carries the genes encoding PT, but does not express them due to multiple mutations in the promoter region (Arico and Rappuoli 1987). B. parapertussis, unlike B. pertussis, does not express BrkA, which is responsible for conferring serum resistance (Goebel et al. 2008). Instead B. parapertussis expresses an O-antigen on its lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which provides serum resistance and promotes bacterial colonization of the respiratory tract (Goebel et al. 2008). Thus the two pathogens, although closely related, have evolved distinct pathogenic mechanisms through expression of different virulence factors.

We previously found that PT contributes to B. pertussis respiratory infection in mouse models by suppression and modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses (Andreasen and Carbonetti 2008, Carbonetti et al. 2003, Carbonetti et al. 2005, Carbonetti et al. 2007, Carbonetti et al. 2004). We hypothesize that this immunomodulatory activity of PT may sensitize B. pertussis-infected hosts to secondary respiratory infections with other pathogens. Since little is known about the dynamics of co-infection with B. pertussis and B. parapertussis, in this study we investigated mixed infection of the two pathogens in the mouse respiratory tract, and hypothesized that the presence of B. pertussis would enhance the ability of B. parapertussis to infect the host.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains

B. parapertussis strain 12822, the type strain whose genome has been sequenced (Heininger et al. 2002, Parkhill et al. 2003), was used in this study. The B. pertussis strains used for this study were streptomycin- and nalidixic acid-resistant derivatives of Tohama I and were produced as previously described (Carbonetti et al. 2003). B. pertussis and B. parapertussis strains were grown on Bordet-Gengou (BG) agar plates containing 10% defibrinated sheep blood. B. parapertussis strains that infect humans are distinct from other Bordetella strains in that they produce a dark pigment when grown on blood agar plates, a phenotype that can be used to distinguish between B. pertussis and B. parapertussis (Ensminger 1953, Heininger et al. 2002). That pigment production correlated with species identity was confirmed by PCR analysis (on 10 pigmented and 10 non-pigmented colonies from a plate with colonies recovered from a mixed infection) using primers from IS481 sequence for B. pertussis and from IS1001 sequence for B. parapertussis (Roorda et al. 2011).

Mouse Infection

All animal experiments conformed to all relevant federal guidelines and institutional policies. Six-week-old female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories) were inoculated intranasally with bacterial suspensions prepared as follows. Bacterial strains were plated from frozen culture on BG blood agar plates, incubated for three days for B. pertussis and two days for B. parapertussis at 37°C, and bacterial growth was then transferred to new plates and allowed to grow for an additional two days. Bacterial strains were resuspended and appropriate dilutions were made in sterile PBS. Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane (Baxter) and inoculated intranasally with 50 μl of inoculum. Viable counts were determined by dilution of a sample of the inoculum, which was then plated on BG blood agar plates, and colonies were counted 4–5 days later. Mice (minimum of 4 per group) were euthanized by carbon dioxide inhalation at defined time points; the lungs and trachea were removed as a unit and homogenized in 2 ml of sterile PBS. Appropriate dilutions of the homogenate were plated on BG blood agar plates and colonies were counted after 4 days of incubation at 37°C to determine colony forming units (CFU) per respiratory tract. 100 colonies per mouse were patched onto BG blood agar plates for determination of pigment production to distinguish between B. pertussis and B. parapertussis and to calculate the ratio of the 2 organisms in the mixture. All experiments were performed at least twice with representative results shown.

Intranasal Administration of PT

PT was purified from B. pertussis liquid culture supernatants using the fetuin-agarose affinity chromatography method (Kimura et al. 1990), dialyzed against PBS and the concentration of the toxin was determined by BCA assay and stored at −80°C until required. Mice were anesthetized and inoculated intranasally with 50 μl containing 100 ng PT. Control mice were inoculated with 50 μl of sterile PBS.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

Mice were first euthanized by inhalation of carbon dioxide and the trachea and lungs were exposed by dissection. A small hole was cut in the top of the trachea and a 20-gauge blunt-ended needle introduced, this was tied in place with surgical thread to prevent needle moving upon introduction of fluid. The lungs were flushed twice with 0.7 ml of sterile PBS, this was repeated to yield a total of 1.4 ml of BAL fluid. Cell counts were performed upon aliquots of the recovered BAL fluid using a hemocytometer and samples were also prepared by cytospin centrifugation and staining for the identification of cell types. Cytospin centrifugation was performed at 600 rpm for 5 minutes and the slides were stained with modified Wright’s stain (Hema 3® Stain Set, Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 100 cells from several microscope fields (5–6) were counted and identified for each sample.

Depletion of Airway Macrophages (AM)

Clodronate (kindly provided by Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was incorporated into liposomes from a 250 mg/ml solution as previously described (Van Rooijen and Sanders 1994). Anesthetized mice were inoculated intranasally with 100 μl clodronate-containing liposomes (CL) or PBS-containing liposomes (PL). Macrophage depletion was determined by analysis of BAL fluid cells as described above, and was routinely >90%.

Neutrophil depletion

Neutrophil depletion was conducted in mice using 1 mg of rat monoclonal antibody RB6 administered by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. The RB6 antibody is specific for Ly-6G (Gr-1) a marker that is expressed predominantly on neutrophils. Mice were treated with antibody one day prior to intranasal bacterial inoculation and every other day subsequently until euthanization. Control mice were treated with 1 mg of purified rat IgG (Sigma). Neutrophil depletion was confirmed by analysis of BAL fluid cells in infected mice and was routinely >95%.

Calculation of Competitive Index

The advantage one strain has over another in a mixed infection can be measured by calculating the Competitive Index (CI). CI is defined as the ratio between strain A (in our case B. parapertussis) and strain B (B. pertussis) in the output, i.e. recovered from the respiratory tract, divided by the ratio of strain A and strain B in the input (the ratio in the inoculum).

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between mean bacterial loads were analyzed by t test, and competitive indexes were log transformed and analyzed by t test (versus a theoretical value of 1).

Results

B. parapertussis outcompetes B. pertussis in mixed infection of the mouse respiratory tract

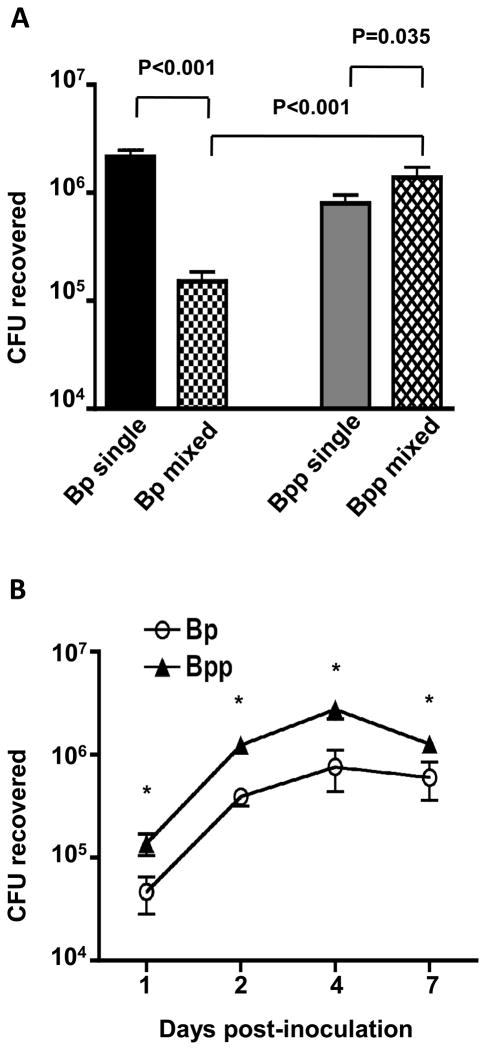

To compare the effect of mixed infection with B. pertussis and B. parapertussis to single strain infections with either pathogen, 6-week-old Balb/c mice were inoculated intranasally with 50 μl of a suspension containing 5 × 105 CFU of B. pertussis and 5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis (mixed infection), or with 50 μl of a suspension containing 5 × 105 CFU of either organism (single strain infection). Seven days post-inoculation (near the peak of bacterial loads in single infections) mice were euthanized, and the bacterial load of each pathogen in the respiratory tract was determined. As shown in Fig. 1A, B. pertussis loads were significantly lower in the mixed infection than in the single strain infection. In contrast, B. parapertussis loads were significantly higher in the mixed infection than in the single strain infection, and in the mixed infection B. parapertussis significantly outcompeted B. pertussis, with a mean of 9-fold more CFU recovered from the murine respiratory tract. The mean competitive index (CI) within the group of 4 mice with mixed infection was 8.9 ± 5.5 (P=0.003). To determine whether the advantage of B. parapertussis was manifest at earlier stages of infection, mice (4 per group) were inoculated as in the previous experiment with a mixed 1:1 inoculum of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis and euthanized at days 1, 2, 4, and 7 post-inoculation. The competitive advantage of B. parapertussis was observed as early as 24 h post-inoculation (mean CI = 7), and was maintained through the peak of infection (Fig. 1B). Together these data indicate that B. parapertussis not only outcompetes B. pertussis in a mixed infection, but also that it benefits from the presence of B. pertussis in the infection.

Figure 1. Dynamics of mixed infection with B. pertussis and B. parapertussis in mice.

A. Mean CFU recovered from the respiratory tract of Balb/c mice inoculated with a 1:1 mix (106 total CFU) of B. pertussis (Bp mixed) and B. parapertussis (Bpp mixed), or with 5 × 105 CFU of B. pertussis alone (Bp single) or B. parapertussis alone (Bpp single), on day 7 post-inoculation. Significant differences are shown by P value. B. Mean CFU recovered from the respiratory tract of Balb/c mice inoculated with a 1:1 mix (106 total CFU) of B. pertussis (Bp) and B. parapertussis (Bpp) on the indicated day post-inoculation. * P<0.05.

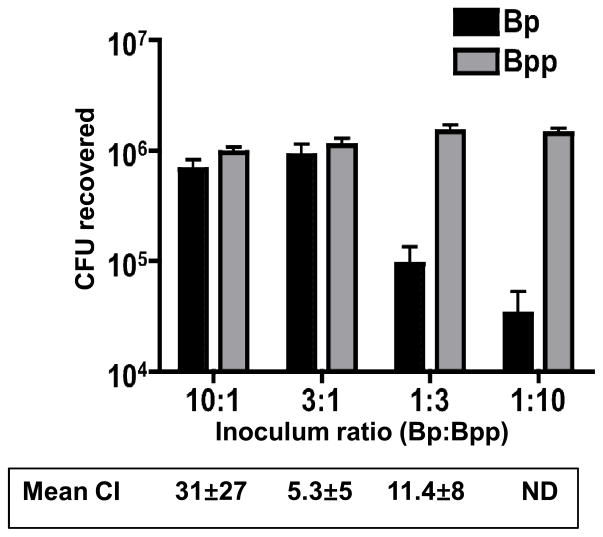

To further explore the competition between these two organisms in a mixed infection, mice (4 per group) were infected with mixed inocula at ratios (B. pertussis to B. parapertussis) of 10:1, 3:1, 1:3 and 1:10 (106 total CFU). Mice were euthanized 7 days post-inoculation, and the bacterial load and ratio of the two organisms determined as before. B. parapertussis outcompeted B. pertussis at all inoculum ratios (Fig. 2). In mice where the inoculum contained B. parapertussis as the predominant strain (1:3 and 1:10), B. pertussis was at a significant disadvantage, with relatively low CFU recovered from the mice (no B. pertussis was recovered from 2 mice in the 1:10 group). Remarkably, even when the inoculum contained a 10-fold excess of B. pertussis (10:1), greater CFU of B. parapertussis were recovered from the host, with a mean CI of 31 (Fig. 2). Overall these data show that B. parapertussis is able to outcompete B. pertussis in a mixed infection over a range of input ratios, and apparently gains a greater advantage (higher CI) when the initial inoculum contains higher numbers of B. pertussis.

Figure 2. Effect of input ratio of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis upon their competitive co-infection.

Mean CFU recovered from the respiratory tract of Balb/c mice inoculated with the indicated ratio of B. pertussis (Bp) and B. parapertussis (Bpp) (106 total CFU) on day 7 post-inoculation. The competitive index (CI) for the first 3 ratios is shown below (ND – not determined due to zero values). All CI values were significantly different from 1 (p<0.05).

B. parapertussis has an early advantage over B. pertussis in staggered infections

To determine whether the advantage to B. parapertussis occurs early in the process of infection, experiments were conducted staggering the inoculation with the two organisms. Two different staggered inoculations were tested: (i) mice were inoculated first with 2.5 × 105 CFU B. pertussis (t0) and 3 h later inoculated with 2.5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis (t3); or (ii) mice were inoculated initially with 2.5 × 105 CFU B. pertussis (d0) and 24 h later inoculated with 2.5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis (d1). Mice from each group were euthanized on day 2 post-B. pertussis inoculation, and bacterial loads and the ratio of the two organisms recovered were determined. In mice inoculated at t0 and t3, greater numbers of B. parapertussis than B. pertussis were recovered (CI = 1.82, P<0.05, data not shown). When the inoculations were staggered by 24 h, neither strain had a significant advantage (CI = 0.9, data not shown) even though B. pertussis colonization began 24 h earlier than that of B. parapertussis. These data indicate that B. parapertussis can outcompete B. pertussis during early infection even when B. pertussis has a “head start”, indicating that the advantage is unlikely to involve the initial adherence steps of the infection.

Co-administration of pertussis toxin enhances infection of the respiratory tract by B. parapertussis

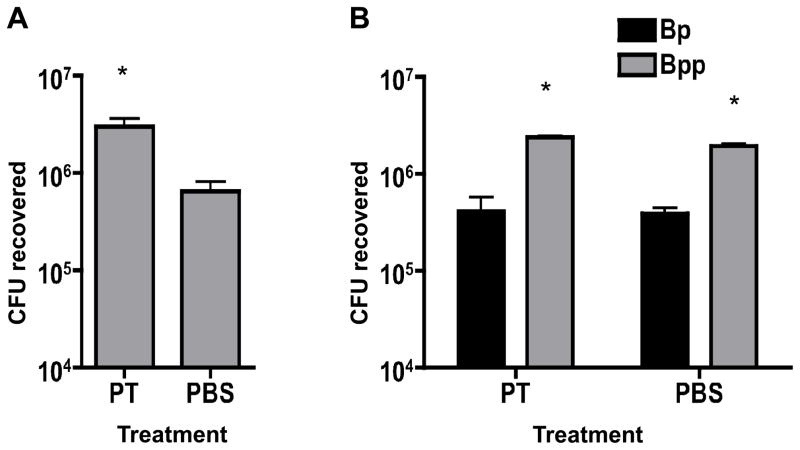

Since B. parapertussis outcompeted B. pertussis and benefited from its presence in mixed infections, we hypothesized that a factor produced by B. pertussis may enhance the virulence of B. parapertussis. A good candidate for this virulence factor is PT, since it is not expressed by B. parapertussis and has been shown to have an important role in the virulence of B. pertussis in this mouse model. We demonstrated previously that bacterial loads of a PT-deficient strain of B. pertussis (ΔPT) were significantly higher when present in a mixed infection with wild type B. pertussis and that intranasal administration of purified PT up to 2 weeks prior to inoculation with the ΔPT strain resulted in a significant increase in bacterial infection (Carbonetti et al. 2003). To test the hypothesis that PT enhances B. parapertussis infection, groups of mice (n=4) were inoculated with 5 × 105 CFU B. pertussis and 5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis (1:1 mix) or 5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis alone, each inoculum containing either 100 ng PT or an equivalent volume of PBS as a control. Mice were euthanized 7 days post-inoculation and the bacterial loads of each pathogen in the respiratory tract were determined. When PT was administered with B. parapertussis alone, a 5-fold increase of CFU recovered was observed compared to that recovered from control mice (p=0.04) (Fig 3A). In the mixed infection, PT addition had no significant effect on the CFU of B. parapertussis (or B. pertussis) recovered (Fig. 3B), which is not surprising since B. pertussis already provides a source of PT during infection. These data support the conclusion that PT enhances B. parapertussis infection and competition with B. pertussis.

Figure 3. Effect of PT co-administration on B. parapertussis infection and on mixed infection of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis.

A. Mean CFU of B. parapertussis recovered from the respiratory tract of Balb/c mice on day 7 post-inoculation with 5 × 105 CFU with co-administered PT or PBS. B. Mean CFU of B. pertussis (Bp) or B. parapertussis (Bpp) recovered from the respiratory tract of mice on day 7 post-inoculation with a 1:1 mix (106 total CFU) with co-administered PT or PBS. * P<0.05.

B. parapertussis infection is not enhanced by mixed infection with a PT-deficient strain of B. pertussis

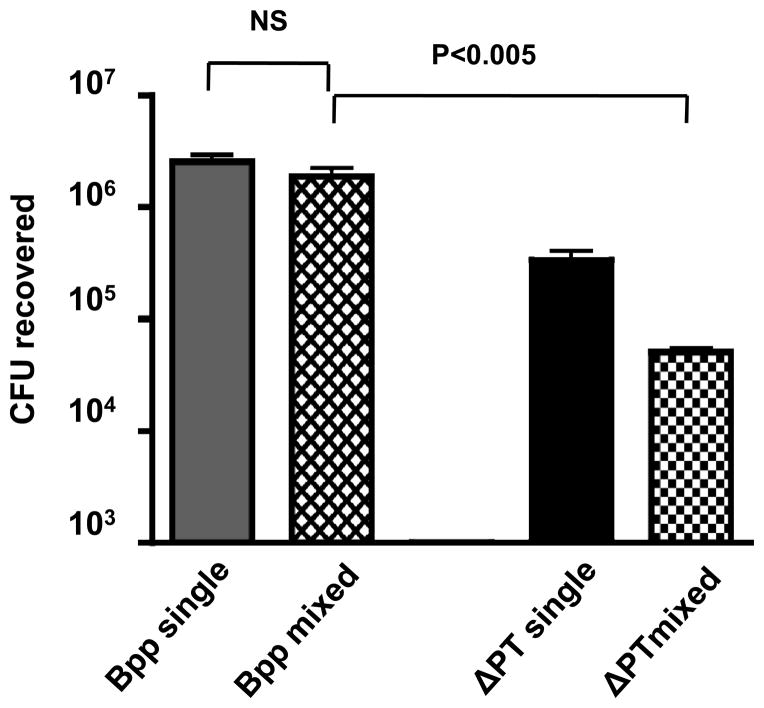

Since PT appears to enhance B. parapertussis infection of the mouse respiratory tract, we hypothesized that B. parapertussis infection would not be enhanced by co-infection with the PT-deficient strain of B. pertussis (ΔPT). Mice (n=4) were infected with mixed inocula of 5 × 105 CFU of B. parapertussis and 5 × 105 CFU of ΔPT. Two control groups (n=4) were inoculated either with 5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis or 5 × 105 CFU ΔPT only. Mice were euthanized 7 days post-inoculation and the bacterial loads of the two organisms were determined. In the mixed infection, B. parapertussis significantly outcompeted ΔPT, with a mean CI of 188 (p=0.002) (Fig 4). However, unlike the result observed in mixed infections with wild type B. pertussis, the recovered CFU of B. parapertussis were not increased by mixed infection with ΔPT, since approximately equal CFU were recovered in mixed and single infections (Fig. 4). These data further support the conclusion that PT enhances B. parapertussis infection during co-infection with wild type B. pertussis.

Figure 4. B. pertussis ΔPT does not enhance B. parapertussis growth in mixed infection.

Mean CFU of B. parapertussis (Bpp) or B. pertussis ΔPT recovered from the respiratory tract of Balb/c mice on day 7 post-inoculation with a 1:1 mix of the 2 strains (106 total CFU) or with 5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis alone (Bpp single) or B. pertussis ΔPT alone (ΔPT single). Significant difference is shown by P value (NS – not significant).

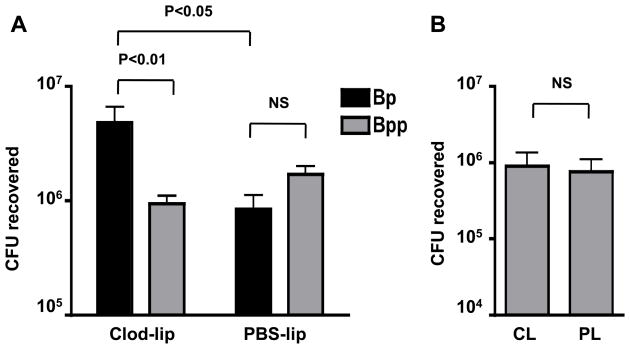

Effect of airway macrophage depletion on co-infection

We previously found that depletion of resident airway macrophages (AM), using intranasally-administered clodronate liposomes (Van Rooijen and Sanders 1994), results in the enhancement of B. pertussis infection and increases bacterial loads of the ΔPT strain to wild type levels (Carbonetti et al. 2007). Since depletion of AM obviates the need for PT production by B. pertussis in order to reach maximal levels of infection, we hypothesized that AM depletion may selectively enhance B. pertussis infection and possibly alter the dynamics of co-infection with B. parapertussis. To test this, mice were treated intranasally with 100 μl clodronate liposomes (CL) or PBS liposomes (PL) as control. 24 h later 2 mice from each group were euthanized and the cell content of broncheoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was analyzed to confirm successful AM depletion (data not shown). Groups of the remaining pretreated mice (n = 4) were inoculated 48 h later with either 5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis or a mixture of 5 × 105 CFU B. pertussis and 5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis (1:1 mix). Four days post-bacterial inoculation mice were euthanized and bacterial loads of the two organisms in the respiratory tracts were determined. Remarkably, AM depletion reversed the outcome of the mixed infection, with significantly higher numbers of B. pertussis than B. parapertussis recovered (mean CI = 16.7) (Fig. 5A). In control PL-treated mice there were greater numbers of B. parapertussis than B. pertussis recovered, though this difference was not significant (Fig. 5A). In mice infected with B. parapertussis alone, AM depletion had no effect on bacterial numbers (Fig. 5B). It is interesting to note that the total bacterial load in the CL-treated mixed infection group was significantly higher than the PL-treated group or the CL-treated group inoculated with B. parapertussis alone (Fig. 5). From these data we conclude that AM depletion does not enhance B. parapertussis infection, suggesting that AM do not play a major protective role early in infection with this organism. This is in contrast to effects of AM depletion on B. pertussis where CL treatment results in enhanced infection of the respiratory tract (Carbonetti et al. 2007).

Figure 5. Effect of resident airway macrophage depletion on B. parapertussis single infection or mixed infection with B. pertussis.

A. Mean CFU of B. pertussis (Bp) or B. parapertussis (Bpp) recovered from the respiratory tract of Balb/c mice on day 4 post-inoculation with a 1:1 mix of the 2 strains (106 total CFU). Mice were pre-treated 2 days prior to bacterial inoculation with intranasal administration of clodronate liposomes (CL) to deplete airway macrophages or PBS liposomes (PL) as a control. Significant difference is shown by P value (NS – not significant). B. Mean CFU of B. parapertussis recovered from the respiratory tract of Balb/c mice on day 4 post-bacterial inoculation (5 × 105 CFU) in CL-treated and PL- treated mice.

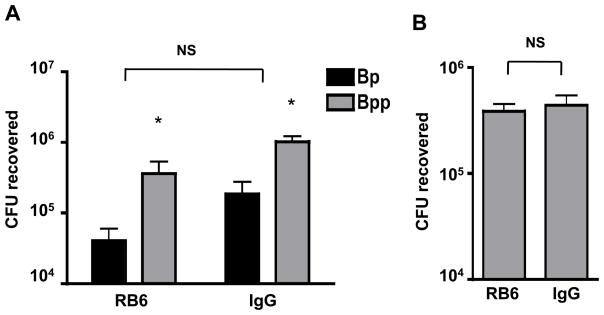

Effect of neutrophil depletion on co-infection

PT inhibits early influx of neutrophils into the respiratory tract in response to B. pertussis infection (Carbonetti et al. 2003, Carbonetti et al. 2005), and this effect is mediated by the inhibition of chemokine upregulation in lung cells in response to B. pertussis infection in the airways (Andreasen and Carbonetti 2008). Neutrophils play a fundamental part in the innate immune response to bacterial infections and are essential in the protection against a number of lung pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Tsai et al. 2000). However, we recently found that neutrophil depletion had no effect on B. pertussis infection in naïve Balb/c mice (Andreasen and Carbonetti 2009). To investigate whether neutrophils play a role in the dynamics of mixed respiratory tract infections with B. parapertussis and B. pertussis, groups of mice were subjected to neutrophil depletion by intraperitoneal injection with 1 mg of rat RB6 antibody, and mice in control groups were injected with the same dose of control rat IgG antibody. 24 h later mice from each group were inoculated with either a mixture of 5 × 105 CFU B. pertussis and 5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis (1:1 mix) or with 5 × 105 CFU B. parapertussis alone. The following day mice were reinjected with the appropriate antibody to maintain neutrophil depletion. Mice were euthanized on day 4 post-inoculation, the respiratory tracts were harvested and the bacterial loads of the two Bordetella species were determined. In neutrophil-depleted mice the competitive relationship between B. pertussis and B. parapertussis was unchanged compared to control mice (Fig. 6A). There was also no significant difference in bacterial loads between neutrophil-depleted and control mice infected with B. parapertussis alone (Fig. 6B). From these data we conclude that neutrophils do not play a major role in the dynamics of these two organisms in co-infection of naïve mice, nor in B. parapertussis infection.

Figure 6. Effect of neutrophil depletion on mixed infection with B. pertussis and B. parapertussis or on B. parapertussis single infection.

A. Mean CFU of B. pertussis (Bp) or B. parapertussis (Bpp) recovered from the respiratory tract of Balb/c mice on day 4 post-inoculation with a 1:1 mix of the 2 strains (106 total CFU). Mice were treated with i.p. injection of either neutrophil-depleting antibody (RB6) or control IgG on the day before bacterial inoculation and every other day subsequently. * P<0.05 (vs Bp). NS – not significant (RB6 vs IgG for either strain). B. Mean CFU of B. parapertussis recovered from the respiratory tract of Balb/c mice on day 4 post-inoculation (5 × 105 CFU) in RB6-treated or control IgG-treated mice.

Discussion

In this study we have demonstrated that infection with B. pertussis enhances the ability of B. parapertussis to colonize the same host in a mixed infection, and that B. parapertussis outcompetes B. pertussis. When mice were co-infected with equal numbers of B. parapertussis and B. pertussis, greater numbers of B. parapertussis were recovered from the mixed infection at the early stages and through the peak of infection. In other studies we found that by day 21 post-inoculation, B. parapertussis was the only organism recovered (data not shown). B. parapertussis outcompeted B. pertussis over a range of inoculum ratios, and when B. parapertussis was the predominant species in the inoculum, B. pertussis was quickly outcompeted and almost cleared from the host at the peak of infection. B. parapertussis still had an advantage when the time of inoculation was staggered, with B. pertussis followed by B. parapertussis at a later time point, from which we conclude that competition for adherence is not the reason for the advantage of B. parapertussis. Overall these results suggest that B. parapertussis gains an advantage over B. pertussis at the very early (but post-adherence) stages of a mixed infection in this mouse model.

Our results differ from those of a recent report (Long et al. 2010), in which no advantage of B. parapertussis over B. pertussis in a mixed infection was observed, and B. parapertussis did not gain an advantage from co-infection with B. pertussis compared to a single strain infection. The reason for this difference is not clear, but may be due to use of a different mouse strain (C57BL/6), different age of mice (10–12 weeks), higher inoculum dose (107 CFU) or different bacterial strains (antibiotic resistant derivatives).

In our study, B. parapertussis not only outcompeted B. pertussis but also was recovered in greater numbers than those observed in infections with B. parapertussis alone. From these observations we hypothesized that B. pertussis may produce a factor that enhances B. parapertussis infection. Since previous investigations in our lab have demonstrated a role for PT in the enhancement of infection with B. pertussis (Carbonetti et al. 2003), we considered that PT may also facilitate infection by B. parapertussis. Co-administration of PT in mice has been shown to enhance infection of PT-deficient strains of B. pertussis (Carbonetti et al. 2003), and also enhances influenza virus infection (Ayala et al. 2011). We found that co-administration of PT with B. parapertussis, which does not produce PT itself, resulted in a significant increase in bacterial load. The effect of co-administered PT was small in the mixed infection, probably because B. pertussis in the inoculum provides a source of PT. This enhancing effect in a mixed infection was lost when a PT-deficient B. pertussis strain was used. We conclude that PT produced by B. pertussis has an enhancing effect upon B. parapertussis infection. PT has immunosuppressive effects on both innate and adaptive immunity to B. pertussis infection (Andreasen and Carbonetti 2008, Carbonetti et al. 2004, Kirimanjeswara et al. 2005), and a suppressive effect on innate immunity is a likely mechanism by which PT enhances B. parapertussis infection.

We also found that AM depletion altered the dynamics of the mixed infection, providing B. pertussis with a significant advantage over B. parapertussis. We previously found that AM depletion enhances B. pertussis infection, but is also associated with an influx of neutrophils (Carbonetti et al. 2007), and so it is possible that this influx has a negative effect upon B. parapertussis infection. However, neutrophil depletion did not enhance B. parapertussis infection or alter its advantage in the mixed infection, calling into question any role for neutrophils in this competition. It is unclear why B. parapertussis did not significantly outcompete B. pertussis in PL-treated control mice, and we cannot rule out the possibility that liposomes had some negative effect on B. parapertussis infection. We can however conclude that AM depletion does not enhance B. parapertussis infection and that AM do not have a major role in protection against infection with this organism, unlike B. pertussis. Therefore, it is unlikely that the enhancing effect of PT on B. parapertussis infection is due to its suppressive activity on AM.

B. parapertussis differs from B. pertussis in the structure of their lipopolysaccharides (LPS). While they have some shared structural elements, B. pertussis lipooligosaccharide (LOS) lacks the O antigen which is present on B. parapertussis LPS (Allen et al. 1998, Caroff et al. 2001, Di Fabio et al. 1992). In vitro, purified B. parapertussis LPS is a stronger activator of the innate immune response than purified B. pertussis LOS with regard to maturation of human dendritic cells (DC) and cytokine production (Fedele et al. 2008). However, a recent report hypothesized that B. parapertussis LPS stimulates the TLR4 response inefficiently, allowing the organism to avoid the robust inflammatory response involved in rapid antibody-mediated clearance (Wolfe et al. 2009). This is in contrast to the LPS of B. bronchiseptica and B. pertussis, which are relatively stimulatory of the TLR4 response in mice (Mann et al. 2005, Wolfe et al. 2009). Wolfe et al. observed that co-infection of C57BL/6 mice with B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis resulted in more efficient control of B. parapertussis infection by the host, concluding that increased neutrophil recruitment due to the presence of B. bronchiseptica LPS led to the more efficient clearance of B. parapertussis (Wolfe et al. 2009). However, these observations are in conflict with those made in our study, where co-infection of Balb/c mice with B. pertussis and B. parapertussis did not result in increased clearance of B. parapertussis, but rather an increase in B. parapertussis numbers. It may be that PT produced by B. pertussis provides B. parapertussis with protection against the TLR4-mediated responses, since PT can inhibit cytokine production and neutrophil recruitment in response to intranasal administration of LPS (Andreasen and Carbonetti 2008). Alternatively the effects may be mouse strain-dependent.

Previous studies with 2-week-old suckling mice demonstrated that when infected with a mixed inoculum of B. pertussis 18-323 and B. parapertussis strain 422, persistent colonization with B. parapertussis was observed (Kawai et al. 1996). However when mice were inoculated with B. parapertussis alone, this organism failed to colonize mice, suggesting a relationship between B. pertussis and B. parapertussis, where the former facilitates colonization by the latter in a mixed infection (Kawai et al. 1996). This group hypothesized that for B. parapertussis to adhere to lung epithelia cells and consequently establish infection, these epithelial cells must first be damaged by B. pertussis infection. In our infection studies we observed a similar relationship between these two species whereby B. pertussis facilitates infection by B. parapertussis. However, unlike in the 2-week-old mice, B. parapertussis alone is able to establish infection in 6-week-old Balb/c mice.

Our study examined the effects of co-infection on early events in naïve hosts. Several reports have examined the effect of immunity to one of these Bordetella pathogens (from vaccination or infection) on infection by the other in mouse models. Current pertussis vaccines do not provide protective immunity against B. parapertussis (Komatsu et al. 2010) and can give this organism an advantage in a mixed infection (Long et al. 2010), although a novel live attenuated pertussis vaccine was found to protect against B. parapertussis by a T cell-mediated mechanism (Feunou et al. 2010). Pertussis vaccination or prior infection may therefore facilitate B. parapertussis infection in human populations, and our results suggest that concurrent B. pertussis infection may do the same. However, as far as we know B. parapertussis infections have not emerged at high levels in the era of pertussis vaccine use, although diagnostics for B. parapertussis infections need to be improved before the picture is clear. Co-infection with these two closely related pathogens may be more common than documented in human pertussis disease and the less virulent of the pair may benefit from the immunomodulatory properties of B. pertussis. Of course, whether this mouse model is representative of human infection is unclear. Some aspects of B. parapertussis infection in mice more closely resemble those of B. bronchiseptica than B. pertussis (Heininger et al. 2002), and it is possible that B. pertussis is better adapted to the human host than B. parapertussis and would outcompete it in a mixed infection in a human. Human volunteer experiments may be necessary to resolve these issues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AI063080. We thank Galina Artamonova and Aakanksha Pant for conducting some of the preliminary mouse infection studies and Charlotte Mitchell for technical advice with BAL.

References

- Allen AG, Thomas RM, Cadisch JT, Maskell DJ. Molecular and functional analysis of the lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis locus wlb from Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:27–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen C, Carbonetti NH. Pertussis toxin inhibits early chemokine production to delay neutrophil recruitment in response to Bordetella pertussis respiratory tract infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5139–5148. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00895-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen C, Carbonetti NH. Role of neutrophils in response to Bordetella pertussis infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1182–1188. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01150-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arico B, Rappuoli R. Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica contain transcriptionally silent pertussis toxin genes. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2847–2853. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2847-2853.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala VI, Teijaro JR, Farber DL, Dorsey SG, Carbonetti NH. Bordetella pertussis Infection Exacerbates Influenza Virus Infection through Pertussis Toxin-Mediated Suppression of Innate Immunity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH, Artamonova GV, Mays RM, Worthington ZE. Pertussis toxin plays an early role in respiratory tract colonization by Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6358–6366. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6358-6366.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH, Artamonova GV, Andreasen C, Bushar N. Pertussis toxin and adenylate cyclase toxin provide a one-two punch for establishment of Bordetella pertussis infection of the respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2698–2703. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2698-2703.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH, Artamonova GV, Van Rooijen N, Ayala VI. Pertussis toxin targets airway macrophages to promote Bordetella pertussis infection of the respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1713–1720. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01578-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH, Artamonova GV, Andreasen C, Dudley E, Mays RM, Worthington ZE. Suppression of serum antibody responses by pertussis toxin after respiratory tract colonization by Bordetella pertussis and identification of an immunodominant lipoprotein. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3350–3358. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3350-3358.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroff M, Aussel L, Zarrouk H, Martin A, Richards JC, Therisod H, Perry MB, Karibian D. Structural variability and originality of the Bordetella endotoxins. J Endotoxin Res. 2001;7:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio JL, Caroff M, Karibian D, Richards JC, Perry MB. Characterization of the common antigenic lipopolysaccharide O-chains produced by Bordetella bronchiseptica and Bordetella parapertussis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;76:275–281. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90348-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diavatopoulos DA, Cummings CA, Schouls LM, Brinig MM, Relman DA, Mooi FR. Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, evolved from a distinct, human-associated lineage of B. bronchiseptica. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e45. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger PW. Pigment production by Haemophilus parapertussis. J Bacteriol. 1953;65:509–510. doi: 10.1128/jb.65.5.509-510.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele G, Nasso M, Spensieri F, Palazzo R, Frasca L, Watanabe M, Ausiello CM. Lipopolysaccharides from Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis differently modulate human dendritic cell functions resulting in divergent prevalence of Th17-polarized responses. J Immunol. 2008;181:208–216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feunou PF, Bertout J, Locht C. T- and B-cell-mediated protection induced by novel, live attenuated pertussis vaccine in mice. Cross protection against parapertussis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel EM, Wolfe DN, Elder K, Stibitz S, Harvill ET. O antigen protects Bordetella parapertussis from complement. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1774–1780. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01629-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heininger U, Cotter PA, Fescemyer HW, Martinez de Tejada G, Yuk MH, Miller JF, Harvill ET. Comparative phenotypic analysis of the Bordetella parapertussis isolate chosen for genomic sequencing. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3777–3784. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3777-3784.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heininger U, Stehr K, Schmitt-Grohe S, Lorenz C, Rost R, Christenson PD, Uberall M, Cherry JD. Clinical characteristics of illness caused by Bordetella parapertussis compared with illness caused by Bordetella pertussis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:306–309. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata S, et al. Mixed outbreak of Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis in an apartment house. Dev Biol Stand. 1991;73:333–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katada T, Tamura M, Ui M. The A protomer of islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin, as an active peptide catalyzing ADP-ribosylation of a membrane protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;224:290–298. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai H, Aoyama T, Murase Y, Tamura C, Imaizumi A. A causal relationship between Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis infections. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:377–381. doi: 10.3109/00365549609037923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A, Mountzouros KT, Schad PA, Cieplak W, Cowell JL. Pertussis toxin analog with reduced enzymatic and biological activities is a protective immunogen. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3337–3347. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3337-3347.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirimanjeswara GS, Agosto LM, Kennett MJ, Bjornstad ON, Harvill ET. Pertussis toxin inhibits neutrophil recruitment to delay antibody-mediated clearance of Bordetella pertussis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3594–3601. doi: 10.1172/JCI24609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu E, Yamaguchi F, Eguchi M, Watanabe M. Protective effects of vaccines against Bordetella parapertussis in a mouse intranasal challenge model. Vaccine. 2010;28:4362–4368. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GH, Karanikas AT, Harvill ET, Read AF, Hudson PJ. Acellular pertussis vaccination facilitates Bordetella parapertussis infection in a rodent model of bordetellosis. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277:2017–2025. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann PB, Wolfe D, Latz E, Golenbock D, Preston A, Harvill ET. Comparative toll-like receptor 4-mediated innate host defense to Bordetella infection. Infect Immun. 2005;73:8144–8152. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8144-8152.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoo S, Cherry JD. Molecular pathogenesis, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of respiratory infections due to Bordetella pertussis and other Bordetella subspecies. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:326–382. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.326-382.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertsola J. Mixed outbreak of Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis infection in Finland. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1985;4:123–128. doi: 10.1007/BF02013576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss J, Stanley SJ, Burns DL, Hsia JA, Yost DA, Myers GA, Hewlett EL. Activation by thiol of the latent NAD glycohydrolase and ADP-ribosyltransferase activities of Bordetella pertussis toxin (islet-activating protein) J Biol Chem. 1983;258:11879–11882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser JM, Hewlett EL, Peppler MS, Selander RK. Genetic diversity and relationships in populations of Bordetella spp. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:230–237. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.230-237.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J, et al. Comparative analysis of the genome sequences of Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Nat Genet. 2003;35:32–40. doi: 10.1038/ng1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JF, Connor K, Donachie W. Isolation and characterization of Bordetella parapertussis-like bacteria from ovine lungs. Microbiology. 1994;140 ( Pt 2):255–261. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roorda L, Buitenwerf J, Ossewaarde JM, van der Zee A. A real-time PCR assay with improved specificity for detection and discrimination of all clinically relevant Bordetella species by the presence and distribution of three Insertion Sequence elements. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatti KM, Wu KH, Tondella ML, Cassiday PK, Cortese MM, Wilkins PP, Sanden GN. Development and evaluation of dual-target real-time polymerase chain reaction assays to detect Bordetella spp. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;61:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai WC, Strieter RM, Mehrad B, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Standiford TJ. CXC chemokine receptor CXCR2 is essential for protective innate host response in murine Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4289–4296. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4289-4296.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Nagai M. Whooping cough due to Bordetella parapertussis: an unresolved problem. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2004;2:447–454. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witvliet MH, Burns DL, Brennan MJ, Poolman JT, Manclark CR. Binding of pertussis toxin to eucaryotic cells and glycoproteins. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3324–3330. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3324-3330.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DN, Buboltz AM, Harvill ET. Inefficient Toll-like receptor-4 stimulation enables Bordetella parapertussis to avoid host immunity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]