Abstract

Symptoms of anxiety and depression often occur in young women after complete hysterectomy and in older women during menopause. There are many variables that are hard to control in human population studies, but that are absent to a large extent in stable nonhuman primate troops. However, macaques exhibit depressive and anxious behaviors in response to similar situations as humans such as isolation, stress, instability or aggression. Therefore, we hypothesized that examination of behavior in ovariectomized individuals in a stable macaque troop organized along matriarchal lineages and in which individuals have social support from extended family, would reveal effects that were due to the withdrawal of ovarian steroids without many of the confounds of human society. We also tested the hypothesis that ovariectomy would elicit and increase anxious behavior in a stressful situation such as brief exposure to single caging. Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) were ovariectomized (Ovx) or tubal-ligated (intact controls) at 3 years of age and allowed to mature for 3 years in a stable troop of approximately 300 individuals. Behaviors were recorded in the outdoor corral in the third year followed by individual temperament tests in single cages. There was no obvious difference in anxiety-related behaviors such as scratching between Ovx and tubal-ligated animals in the corral. Nonetheless, compared to tubal-ligated animals, Ovx animals exhibited a significant decrease in (1) positive social behavior, (2) initiating dominance behavior (3) time receiving grooming, (4) locomoting, (5) mounting behavior, and in (6) consort behavior. However, Ovx females exhibited a significant increase in (1) consummatory behavior and (2) object play compared to tubal-ligated controls. In the individual temperament tests, Ovx individuals exhibited an increase in anxiety-related behaviors. There was no difference in adrenal weight/body weight suggesting that neither group was under chronic stress. These data indicate that ovarian hormones enable females to successfully navigate their social situation and may reduce anxiety in novel situations.

Introduction

Women experience ovarian failure and loss of ovarian steroid production around 50 years of age. Thus, with extended life spans, a woman may live 35–40 years without ovarian steroids. A number of reports indicate that after menopause, a significant number of women become more anxious, and less able to cope with stress, leading to new onset of depression [1–4]. Younger women who undergo complete hysterectomy have a premature “surgical” menopause, with acute symptoms that are worse than natural menopause [5]. In behavioral and neurobiological studies of human menopause, it has been difficult the isolate the effects of ageing from steroid withdrawal. Moreover, there are other variables in human existence, such as genetics, social support and economics, which could impinge upon mood or anxiety and confound emotional regulation after loss of ovarian steroid secretion.

Macaques are an excellent model in which to study the underlying neural mechanisms of affective disorders due to the removal of ovarian steroids. They have a menstrual cycle, and neural regulation of their menstural cycle is identical to that of women. In addition, they are social animals that exhibit behaviors that have been linked to anxiety and psychosocial stress [6, 7]. For example, stress sensitive macaques have a higher basal heart rate similar to humans [8], and they exhibit more agitated behavior, a primate index of anxiety [9]. In order to understand the effect of ovarian steroids without the confound of age, many studies have used adult female macaques that are ovariectomized, with and without hormone replacement [10–13]. Moreover, the availability of old, perimenopausal macaques is extremely limited [14].

In nonhuman primates, a number of studies have examined the effect of ovariectomy on sexual behavior [15, 16], social status [17] and agonistic behavior [18], but less information is available on the effect of ovariectomy on anxious or depressive behavior. In one study, estrogen (E) treatment of ovariectomized macaques decreased scratching, an indicator of anxiety [19]. Also, when group housed female rhesus macaques were ovariectomized from 4 months to 20 years, and then treated with E, there was a decrease in overall anxiety, whereas administration of tamoxifen, an estrogen antagonist, increased overall anxiety [20]. In these studies, the macaques were not related and lacked social support from mothers and siblings. Thus, further questions about the effect of ovariectomy on anxious or depressive-behavior in macaques with social support from extended family were of interest due to the similarity to human conditions.

The serotonin system plays a pivotal role in affective disorders, including depression and anxiety. In monkeys, we showed that short-term ovariectomy reduced serotonin neural function [10], reduced serotonin neuronal health [21] and increased DNA fragmentation in serotonin neurons [22]. Thus, serotonin neurons exhibit signs of neuroendangerment after ovariectomy, which could lead to serotonin cell death with time. Together, these actions could translate to increased anxiety or depression and/or reduced stress resilience. Therefore in this study, we sought to assess the effects of ovariectomy on socio-emotional behavior in young adult females. To this end, we conducted behavioral observations and temperament testing on long-term ovariectomized female Japanese macaques maintained in a semi-free ranging troop with well-established matriarchal lineages. Age and lineage matched control monkeys were subjected to tubal ligation in order to maintain ovarian function, but to prevent pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC) approved this study, which followed the guidelines set forth by both Animal Welfare Act [23] and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NRC 1996).

Animals

Ten pubertal females 3 years of age, born into a troop of Japanese macaques housed in a naturalistic setting were chosen. At the time, there were 12 matriarchal lineages in the corral. Five pairs of juvenile females were selected that were matched between treatment groups in terms of the dominance hierarchy. One individual of each pair was ovariectomized (Ovx; reproductive tract remains) and the other individual was sterilized by tubal ligation, but the ovaries remained intact. The surgeries were conducted during the annual round up of all of the animals in the corral. The animals were returned to the troop and allowed to mature for 3 years. One animal from each treatment group died in the troop during year 1 and was replaced with animal of similar age. Behavioral testing (see below) was performed during the third year. The animals were euthanized after all testing was completed. The adrenal to body weight ratio was obtained.

Description of the troop

The monkeys used in this study were part of a troop of approximately 300 individuals (aged 0–35 years) housed in a two-acre outdoor corral at the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC). The corral was surrounded by steel walls, and contained several platforms and climbing structures for play and exploration. A 5×5 meter observation tower overlooking the corral allowed for unobtrusive observations. Monkeys were fed commercially available monkey chow twice daily, supplemented by daily fresh produce or grains. Water was available ad libitum. As part of general animal husbandry of ONPRC, all animals were given unique markings on their backs, allowing for individual identification of all members of the troop from the observation tower. Animal care staff walked through the corrals daily to look for sick or injured monkeys. Japanese macaques are seasonal breeders, and at the ONPRC, the birth season was typically between May and August, with the majority of births occurring in June and July. The mating season was typically November through February.

The troop has been the subject of extensive behavioral studies since it arrived at ONPRC in 1965 [24, 25]. The troop composition is relatively stable and the age structure is comparable to that of a natural troop [26]. Like other macaque species, the hierarchical organization of the troop is along matriarchal lineages. Females stay with their mothers their whole lives, and thus young females are typically located close to their mothers, sisters and their daughters, maternal grandmother, and maternal aunts and their daughters. While young males do not emigrate from the ONPRC troop as they would in a natural group, they do spend significantly less time with their mothers after about 1–2 years of age (personal observation). The matriarchal lines and dominance hierarchies within the troop are well documented, and have remained relatively stable for the past 45 years. For the purposes of this study, dominance rank was broken into terciles. The four most dominant lineages were classified as “dominant”, the four least dominant lineages were classified as “subordinate” and the remaining lineages were considered “moderate”. In the last several years, a microsatellite analysis of the DNA of the entire troop has been conducted and the paternity of all the individuals and their relatedness has been established.

Annual round ups

At least once a year, the animals are “rounded up”, or brought from the corral into a capture run (“catch area”) adjacent to the corral. This round up allows collection of the monkeys for procedures that could not be done in an open field, such as annual veterinary exams, weighing and dye marking. Typically, the monkeys are brought into this area one or two times per year, and so most are acclimated to this procedure. During the round-up, monkeys run through tunnels into the catch area, where they jump into transport boxes for transfer to single cages. Round ups are done in the fall, after the birthing season, and before the mating season. In addition to the physical examination, animals are also weighed and tested for tuberculosis, and new infants are identified. The animals are typically kept in standard monkey cages in the catch area for approximately one week.

Surgeries

Subjects were either ovariectomized (Ovx; n=5) or tubal-ligated (intact or TL; n=5) at age three (adolescent, pubertal), and returned to their semi-free ranging troop until the age of six. For ovariectomy or tubal ligation, each animal was sedated with ketamine (10 mg/kg) in its cage in the catch area and transported to a surgical suite. Ovariectomy and tubal ligation were performed by the surgical personnel of ONPRC using a laparoscopic approach.

Corral Behavior

To assess behavior of the monkeys in their home environment, 10-minute focal observations were obtained on the subjects in the corrals during the last year of the study. Observations were conducted in the height of both the mating (December-February) and birthing (i.e., non-mating; May–June) seasons. During each of these seasons, monkeys were observed 2–3 times per week. The order of observations was randomized, to ensure that animals had an equal probability of being observed in relationship to daily events such as morning feedings. All observations were taken in the morning, between 8 am and noon. Japanese macaques are adapted to relatively cool environments, and in the summer months the monkeys tend to decrease activity in the early afternoon, as the temperature increases. For consistency, winter observations were obtained in the mornings as well. Researchers at ONPRC have been watching this troop for over 40 years, and the monkeys are acclimated to the presence of humans in the observation towers and take little notice of their presence.

Table 1 details the ethogram of the behaviors coded in this study. Behaviors were organized into three behavioral classes, social behavior, non-social behavior, and events. Behaviors within the social and non-social behavioral class were mutually exclusive, but could co-occur with behaviors from the other class (e.g., an individual cannot be alone and touching another animal, but could be alone and stationary). Behaviors that naturally occurred in relatively short durations, such as scratches or threats, were classified as “events”. A trained observer utilized instantaneous focal sampling techniques [27] in which the social and non-social behavior of the subject was recorded at 15sec intervals for the 10 min. Because events had relatively short durations, we used all occurrence sampling to record these behaviors (i.e., the observer recorded the number of times the focal individual engaged in the behavior). For social behaviors in which the focal individual could be the receiver or initiator (e.g., grooming), the age class (i.e., adult, sub-adult, juvenile) and gender of the partner were recorded. When feasible, we also recorded whether or not the partner was a close family member (e.g., mother, sister, aunt), however this was not always possible. For the purposes of this study, we focused our analysis on behaviors that might indicate anxiety (e.g., scratching, stereotypies); social behaviors (e.g., any social interaction, grooming, aggressive behaviors); some non-social behaviors (e.g., time spent in consummatory behavior, locomoting or playing with objects or on structures), and sexual behavior (e.g., consorting with males or mounted by males).

Table 1. Ethogram of the behaviors that were monitored in the outdoor corral.

Behaviors coded during focal observations.

| Behavioral Class | Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Social Behaviors (measured in percent of time) | Consort | Focal individual is with male engaged in male guarding, grooming, copulation. Typically occurs over several hours. |

| Groom | Focal individual is picking at hair and/or skin of another individual (focal can initiate or receive behavior) | |

| Proximity | Focal individual is within arms length of another individual without touching | |

| Social play | Focal individual playing with other individuals | |

| Touch | Focal is in physical contact with another individual | |

| Ventral contact | Special case of touch, in which ventral surface of both animals are in contact | |

| Positive social behavior* | Combined behavior which includes groom, proximity, receive groom, touch or ventral contact | |

| Nonsocial behaviors (measured in percent of time) | Handling and ingesting food and/or water | |

| Consummatory behavior | ||

| Locomotion | Movement- e.g., walk, run | |

| Object play | Focal individual manipulates object (e.g., toys or structures in the corral) other than food | |

| Self groom | Focal individual grooms self | |

| Sleep | Focal individual is sitting with eyes closed, usually huddled with other individuals | |

| Stationary | Focal individual sitting quietly, not engaged in other behavior | |

| Stereotypical behavior | Repetitive behavior with no apparent purpose, such as pacing or circling. | |

| Events (measured as frequency) | Aggression | Bite, hit, slap (focal can initiate or receive behavior) |

| Chase | Common usage (focal can initiate or receive behavior) | |

| Displace | Individual leaves promptly upon being approached (focal can initiate or receive behavior) | |

| Fear grimace | Focal individual bars teeth (focal can initiate or receive behavior) | |

| Lipsmack | Rapid movement of lips (focal can initiate or receive behavior) | |

| Mount | Male grasps females legs with his feet with his hands on her back, usually for copulation. | |

| Scratch | Common usage | |

| Threat | Open mouth threat gesture (focal can initiate or receive behavior) | |

| Yawn | Common usage | |

| Dominance-related behavior* | Combined behavior which includes aggression, chase, displace and threat (focal can initiate or receive behavior) | |

Whenever possible, the partner’s ID was recorded as well.

Behaviors within the social or nonsocial behavioral class were mutually exclusive, but could co-occur with behavior from the other behavioral class. Events were measured only as frequencies

We took 12 focal observations on each individual during the birthing and mating seasons of the final year. We averaged data across each season for a total of two observation time points per individual. The effect of ovariectomy on behavior during these time points is reported.

Temperament assessment

To measure anxious behavior and behavioral inhibition, we assessed temperament on all subjects at the end of the study, after the subjects had matured in their natal troop. This testing was performed in early-October (between birthing and mating seasons) during the week in which the animals were located in the catch area for their annual exams.

Subjects were temporarily brought from the catch area to an indoor testing suite located in another building, for a series of two tests (Human Intruder Test and Novel Object Test). For the tests, subjects were housed in a single cage for approximately one hour, including a 12-minute acclimation period, during which they were videotaped from behind a one-way mirror.

Human Intruder Test

This test was designed to measure anxious and depressive-like behaviors in rhesus monkeys [28]. It assesses the behavioral response of a monkey to three stressful conditions: being alone in an unfamiliar cage, being in the presence of a human stranger whose gaze is diverted (Profile epoch; a non-threatening social stimulus), and being in the presence of a human stranger making direct eye contact (Stare epoch; a threatening social stimulus). The typical response of the monkey to the above situation as described by Kalin and Shelton [28] includes freezing when during the profile epoch, and threatening during the stare epoch.

The monkeys were brought individually from the catch area to the behavioral testing room, placed alone in a standard monkey cage in a novel room and videotaped from behind a blind. The test began with a 12-minute acclimation period (Control 1). After this time period, an unfamiliar human entered the testing room and approached to 0.3 m of the cage, taking care not to make eye contact with the monkey. The human presented facial profile to the monkey for 2 minutes (Profile). The human then left the room, leaving the monkey alone for another 2 minutes (Control 2). The human stranger re-entered the room, approached to 0.3 m of the cage, and made continuous, direct eye contact for 2 minutes (Stare). Direct eye contact is generally considered to be a threatening facial expression for monkeys. After the human intruder left, the monkey was videotaped for another 2 min (Control 3). Behaviors that were scored during this test include vocalizations, movement, and reaction to stranger, including freezing, fearful and threatening expressions as listed in Table 2. After finishing, the Novel Object test commenced.

Table 2.

Ethogram of the behaviors that were monitored in the temperament tests (Human Intruder and Novel Object tests). Behaviors within the two behavioral classes were mutually exclusive, but could co-occur with behavior from the other behavioral class.

| Behavioral Class |

Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior in cage | Freeze | Tense body posture with no movement and no vocalization |

| Locomotion | Active behavior resulting in movement from original location (e.g., moving across cage) | |

| Object explore | Intentional exploration of novel object; includes intentional touching, manipulating and/or eating the object | |

| Sleep | Focal individual is sitting with eyes closed, usually huddled with other individuals | |

| Stationary | Focal individual sitting quietly, not engaged in other behavior | |

| Stereotypical behavior | Repetitive behavior with no apparent purpose, such as pacing or circling. | |

| Behavior towards human intruder or novel object | Fear grimace | Focal individual bars teeth |

| Lipsmack | Rapid movement of lips | |

| Scratch | Common usage | |

| Teeth grind | Audible grinding of teeth | |

| Threat | Any threatening behavior directed towards the intruder; includes shaking cage, open mouth facial expression, intense staring with eyes wide open and/or ears pulled back) | |

| Vocalizations | Coos, shrieks, bark | |

| Yawn | Common usage | |

Novel Object Test

This test was designed to test the monkey's reaction to various novel objects, including an ecologically relevant novel object with reward value (i.e., a piece of unfamiliar fruit), a brightly colored toy and a rubber snake. After the Control 3 period of the Human Intruder test, the same human stranger entered the room again and placed a slice of novel fruit (kiwi) in the feeding hole in the cage. The human then left the room, and the monkey was videotaped for five minutes. After five minutes, the human re-entered the room and placed a brightly colored bird toy on the outside of the cage, right above the feeding hole. The toy was placed so that the monkey could inspect and manipulate the object. The stranger re-entered the room after 5 minutes, removed the toy, and placed a rubber snake, modeled to look like a natural predator, on a tray located on the outside of the cage. A piece of apple, a familiar food item, was placed next to the snake such that the monkey had to reach over the snake in order to get to the apple. The snake and apple were left on the tray for five minutes after which the test was ended and the monkey was returned to the catch area. Behaviors scored included vocalizations, movement, and reaction to the object, including the latency to inspect and manipulate the object (see Table 2).

The 2 tests used to assess anxious behavior have been used extensively at the ONPRC in young rhesus macaques [29,30]. All test animals received their standard morning meal approximately two hours prior to the advent of the testing, in order to remove the confound of hunger during the tests. All tests were videotaped and behaviors scored using a computer program (Observer Video Pro, version 4.0, Noldus Information Technology, The Netherlands) by a person blind to the ovarian status of the monkeys. The behaviors assessed have been used in many studies of nonhuman primates to detect differences in temperament, fear and anxiety [31–33]. The tests were performed consecutively in close succession to each other and thus a reaction of a monkey to a prior test could influence its behavior on a succeeding test. We recognize this possible interaction between tests, however since our primary goal in this work was to identify “anxious” versus “less anxious” individuals (i.e., characterize individual differences in behavior/temperament), we believe that it was most important to perform the series of tests in a standardized manner.

Behavioral variables were calculated as percent of time the animal engaged in that behavior. In the novel object test, we also calculated latency to manipulate each of the novel objects. If the monkey did not manipulate the object within 5 minutes, it was given the maximum latency score of 300 seconds.

Statistics

For all variables, assumptions of normality were tested. When necessary, data were normalized with log or square root transformations. When no transformations normalized the data, nonparametric analyses were utilized. Alpha values were set at 0.05.

Corral behaviors in year 3 were compared with repeated measures 2-way ANOVA, with treatment (Ovx vs intact) as one factor and season (birthing or mating) as the repeated measure. Because there is no non-parametric equivalent to this test, for variables in which the data were not normalized, we applied nonparametric statistics on each season separately, yielding fewer degrees of freedom per test. Temperament test behaviors obtained at the end of year 3 were compared with a t-test or Mann Whitney U test (when data were not normally distributed). Some data in the novel object tests were measured as latencies (i.e., amount of time until the specific event, such as touching the object). These data were analyzed using survival analysis, specifically the Log-Rank Test. In situations in which the data were bimodally distributed (e.g., animals either did or did not engage in a particular behavior), we categorized the data into “responders” and “non-responders” and utilized a Pearson’s chi square test for analysis. Statistical analysis was performed with Systat (Systat Software Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Rank, relatives and family composition

Table 3 outlines dominance rank of the subjects during the behavioral observations. There were no statistical differences between the two groups with respect to dominance rank (chi square= 1.67, df=2, p=0.44). Table 3 also details the number of close relatives (e.g., mother, maternal grandmother, sisters and their daughters, maternal aunts and their daughters and any infants (male or female) born to one of these relatives) present in the corral during the time of the observations. There was no difference in the number of close relatives between the Ovx and intact monkeys (Student t=1.173, df=8, p=0.274). Sisters or cousins of three of the Ovx monkeys had infants born during the birthing season.

Table 3.

Details on dominance and social support for 5 ovariectomized (OVX) and 5 tubal-ligated (TL) Japanese macaque females. Animals were categorized into dominant (D), moderate (M) or subordinate (S) dominance status while in the corral. Social support was determined by the number of close female relatives (mother, maternal grandmother, sisters and their daughters, and maternal aunts and their daughters) present in the corral during the time of observations.

| Social Support | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Monkey | Dominance Status | Mother in corral | Close female relatives |

| OVX 1 | M | Y | 5 |

| OVX 2 | M | N | 2 |

| OVX 3 | S | Y | 5 |

| OVX 4 | M | Y | 1 |

| OVX 5 | D | Y | 5 |

| TL 1 | M | Y | 6 |

| TL 2 | D | Y | 2 |

| TL 3 | M | N | 1 |

| TL 4 | M | N | 1 |

| TL 5 | D | N | 0 |

Behavior in the corral

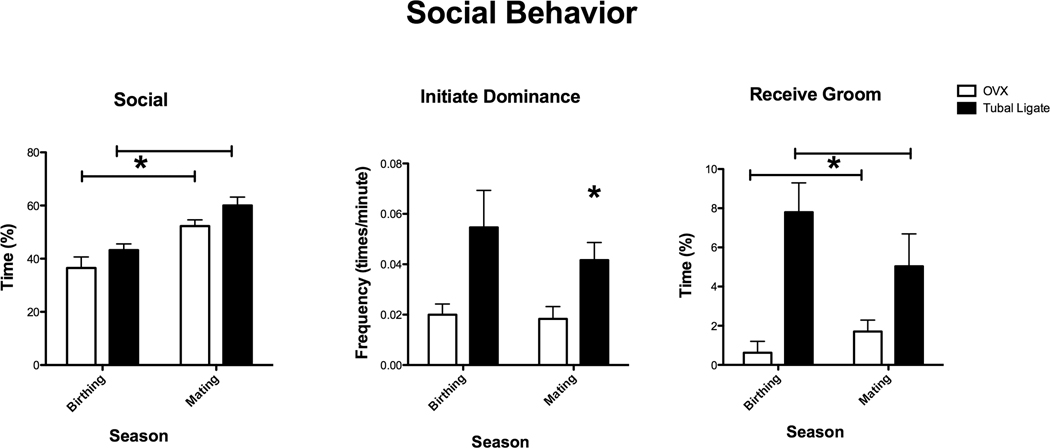

There was a significant effect of season on amount of positive social contact (F (1,8)= 21.208, p=0.002; Figure 1). Focal monkeys spent less time in positive social contact (e.g., touch, groom, ventral contact) with others during the birthing season than in the mating season. There was also a significant effect of treatment on positive social contact (F (1,8)= 8.129, p=0.02). Ovx monkeys spent less time in social behavior (and more time alone) than intact monkeys. There were no differences between Ovx and intact monkeys with respect to specific social behaviors, such as initiating grooming (F(1,8)= 2.67, p=0.14), ventral contact (Birthing season: Mann-Whitney U= 7.5, p=0.28; Mating: U= 15.0, p=0.60), proximity (F(1,8)= 0.51, p= 0.50), social play (Birthing: U= 10.0, p= 0.60; Mating: U= 18.0, p= 0.25) or touch (Birth season: U= 14.0, p=0.75; Mating: U= 4.0, p=0.08). There were differences in dominance-related behaviors, including aggression, chase, and threat (Figure 1). Intact monkeys initiated these behaviors significantly more than Ovx monkeys in the Mating season (Mann Whitney U= 2.0, P=0.03), but not in the Birthing season (Mann Whitney U= 5.0, p=0.11). The intact monkeys also received more grooming from other monkeys (another sign of dominance) than Ovx monkeys (F (1,8)=16.05, p=0.004; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percent of time OVX and tubal ligated (intact) Japanese macaques spent in positive social contact (touch, groom, ventral contact), frequency of dominance behaviors (aggression, chase, displace, threat) and percent of time monkeys spent being groomed by others (receive groom) during behavioral observations taken during the mating and birthing seasons. All animals spent more time engaged in positive social behaviors in the mating season compared to the birthing season (F (1,8)= 21.208, p=0.002). Regardless of treatment, OVX monkeys spent less time in these behaviors compared to intact animals (F (1,8)= 8.129, p=0.02). Intact monkeys initiated dominance-related behaviors significantly more than Ovx monkeys in the mating season (Mann Whitney U= 2.0, P=0.03), but not in the birthing season (Mann Whitney U= 5.0, p=0.11). The intact monkeys also received more grooming from other monkeys than Ovx monkeys (F (1,8)=16.05, p=0.004).

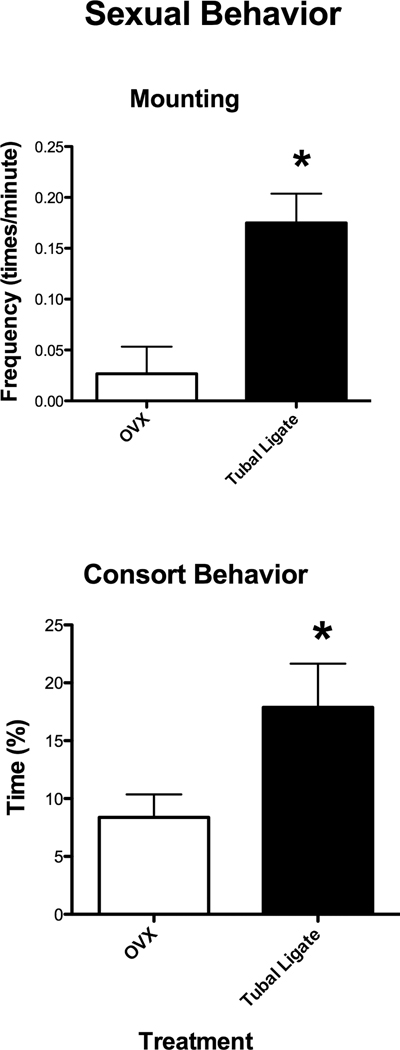

There were also differences between Ovx and intact animals with respect to mating behaviors. Because these behaviors typically only occur in the mating season, analysis for these variables is restricted to that time period. The intact females were mounted by males more during this season than the Ovx females (Mann Whitney U= 1.00, p=0.01; Figure 2) and tended to spend more time in consortship behavior (e.g., grooming, touching, ventral contact, and close social proximity) with males than the Ovx monkeys (t= −2.23, df=8, p=0.056; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The frequency of mounting behavior and percent of time spent in consort behavior (e.g., grooming, touching, ventral contact, and close social proximity with males) for OVX and tubal-ligated (intact) Japanese macaques during behavioral observations taking during the mating season. The intact monkeys were mounted by males more than the Ovx (Mann Whitney U= 1.00, p=0.01) and tended to spend more time in consortship behavior with males than Ovx monkeys (t= −2.23, df=8, p=0.056).

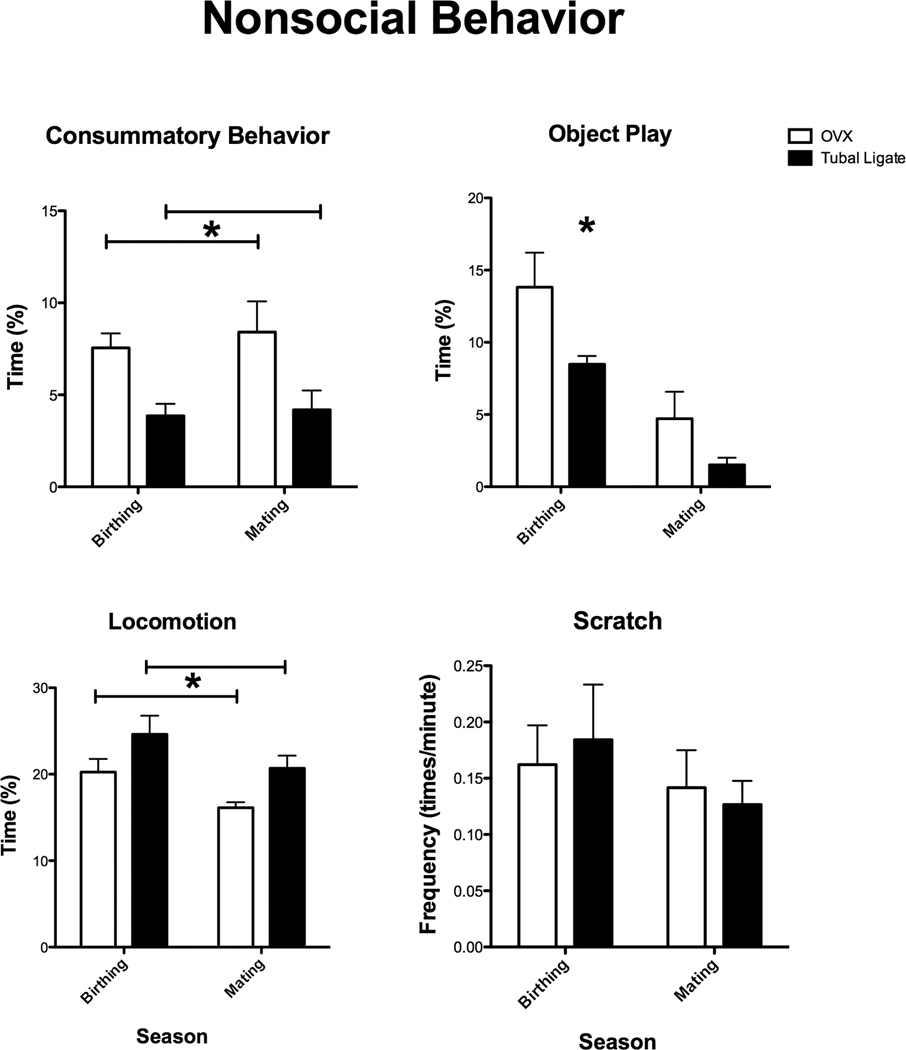

The monkeys in our study exhibited no yawning, stereotypical behavior or other abnormal behaviors. They did exhibit some scratching, although it was not a common occurrence (Mean for all animals= 0.16 +/− 0.02 scratches/min). There were no differences between treatments or across season with respect to this behavior (treatment: F (1,8)= 0.023, p=0.884; season F (1,8)= 2.125, p=0.183; Figure 3). There was, however, a significant effect of treatment on consummatory behavior (F (1,8)=12.94, p=0.007; Figure 3). Regardless of the time of year, Ovx monkeys consumed more food and water than the intact monkeys. The Ovx monkeys also spent more time in object play than intact monkeys during the birthing (Mann Whitney U= 22.5, p= 0.04) but not mating (Mann Whitney U= 18.5, p=0.21) seasons. However, the intact animals tended to spend more time locomoting than the Ovx monkeys (F (1,8)= 4.976, p=0.056; Figure 3). There were no differences between Ovx and intact animals with respect to the other non-social behaviors, including self-groom (F (1,8)= 0.59, p= 0.46), sleep (Birthing: Mann Whitney U= 5.0, p=0.11; Mating Mann Whitney U= 9.0, p= 0.41), or stationary (F (1,8) = 4.460, p= 0.07).

Figure 3.

Figure 3: Percent of time OVX and tubal ligated (intact) Japanese macaques spent in consummatory behavior, interacting with objects (object play), locomotion and the frequency of scratches during behavioral observations taken during the birthing and mating seasons. Ovx monkeys consumed more food and water than the intact monkeys (F (1,8)=12.94, p=0.007). They also spent more time in object play than intact monkeys during the birthing (Mann Whitney U= 22.5, p= 0.04) but not mating (U= 18.5, p=0.21) seasons. Intact monkeys spent more time walking and running than the Ovx monkeys (F (1,8)= 4.976, p=0.056). There were no difference between OVX and intact animals with respect to frequency of scratch (F (1,8)=0.02, p=0.88).

Temperament assessment

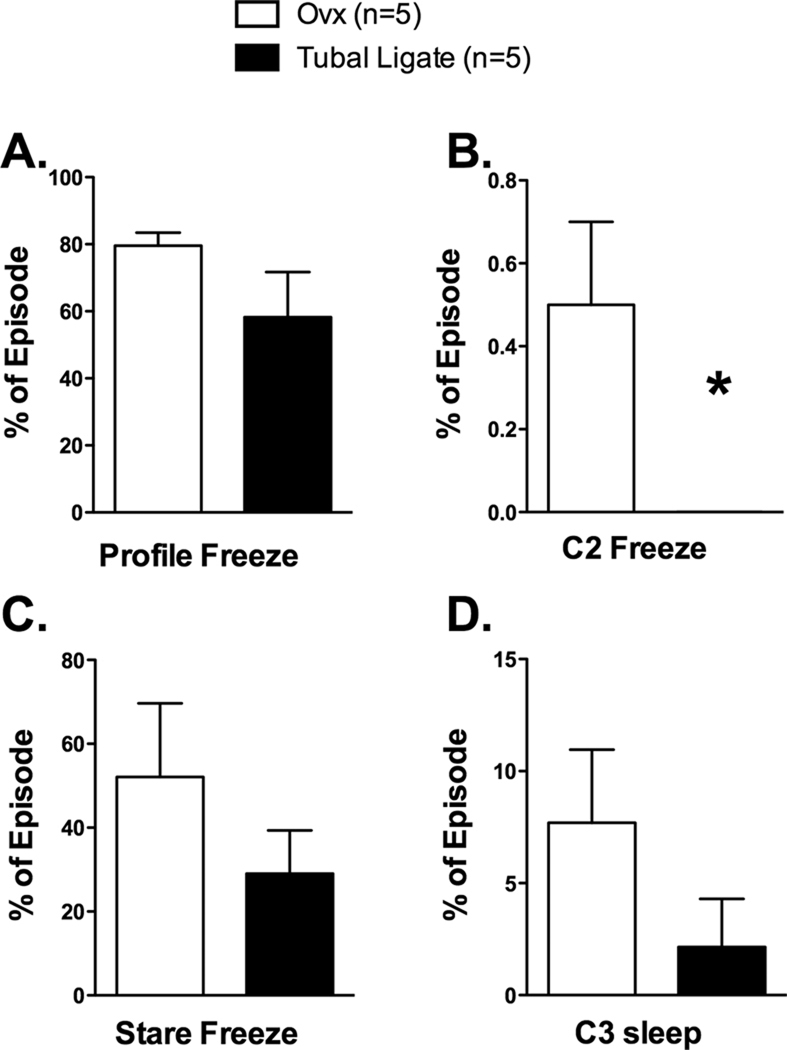

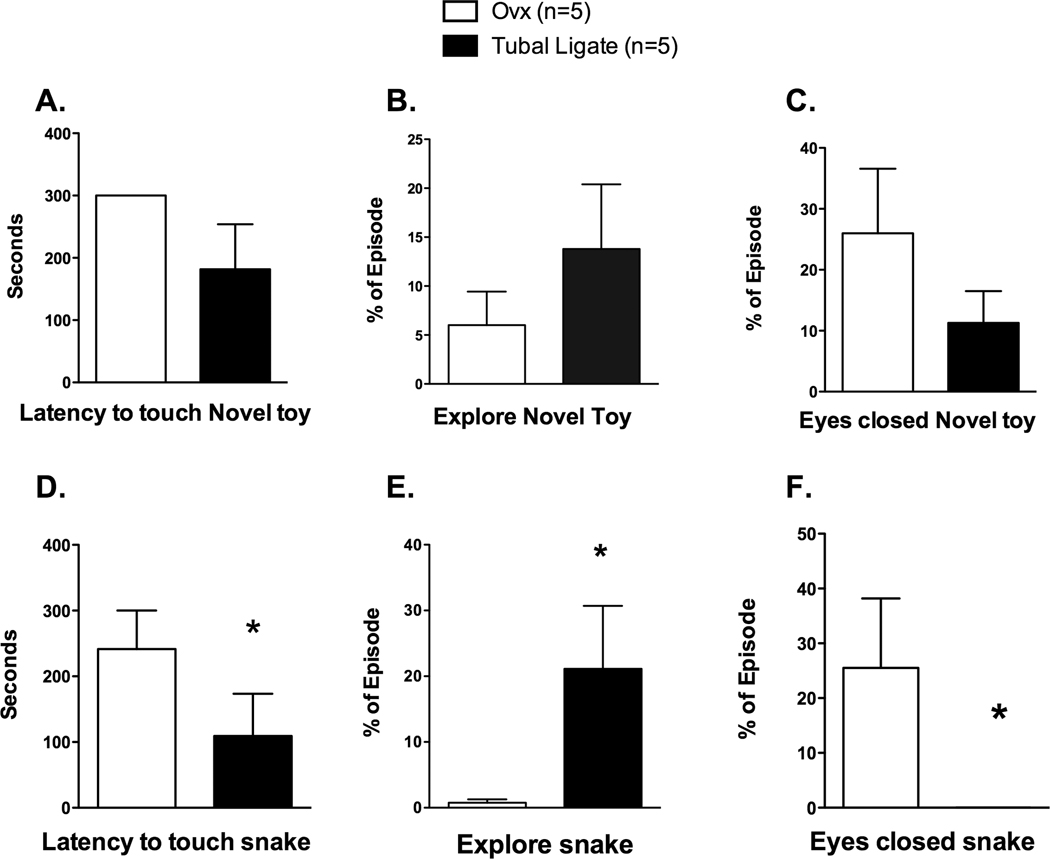

In mid-October of 2009 (immediately prior to mating season), the animals in the corral were rounded–up and the study females were moved to the catch area along with other members of the troop. During this time, they underwent temperament assessment using the Human Intruder and Novel Object tests. The results are shown in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4.

Illustration of selected behaviors observed during the Human Intruder test conducted in year 3. [A] Ovx females tended to freeze longer than tubal ligated animals when exposed to a human profile (t-test = 1.52, df=8, p = 0.17). [B] During the following control period 2 (C2), the OVX monkeys were more likely to continue to freeze than were the tubal-ligated females (Pearson’s Chi square = 4.29, df = 1, p = 0.04). [C] Ovx females tended to freeze longer than tubal-ligated animals when exposed to a human making direct eye contact (Stare; Mann Whitney U= 19.0, p=0.18) and [D] After the human intruder left (Control 3), the Ovx monkeys tended to sleep more than the tubal-ligated monkeys, but the difference was not statistically significant (Mann Whitney U=18.0, p=0.19)

Figure 5.

Illustration of selected behaviors observed during the Novel Object tests conducted in year 3. Each animal was exposed to a novel food (kiwi), a novel toy and a rubber snake. There was no difference between the groups in the latency to touch or amount of time spent exploring the kiwi (data not shown). [A] None of the Ovx animals and only two of the intact touched the toy within the 5 min (300 sec) episode. When we categorized the responses there was no statistically significant difference between the groups (Chi square= 2.50, df= 1, p=0.11). [B] There was no difference between the groups in the time spent exploring the toy (Mann Whitney U= 10.5, p=0.64). [C] There was no difference between the groups in the percent of time spent with eyes closed in the presence of the toy (Mann Whitney U= 17.0, p=0.33). [D] Intact animals were more likely than Ovx animals to approach and touch the snake during the 5 min period (Chi square = 3.60, df= 1, p= 0.058). [E] The Ovx animals spent significantly less time exploring the snake than the intact monkeys (Mann Whitney U= 3.5, p=0.05).

[F] There were significant differences in whether or not the monkeys fell asleep in the presence of the snake (Chi square= 6.67, df= 1, p= 0.01). Four of the OVX and none of the intact monkeys fell asleep during this episode.

There was a wide range of responses to the human intruder in the human intruder test. Ovx monkeys tended to freeze longer during the Profile and Stare episode than intact monkeys (Profile: t-test = 1.52, df=8, p = 0.17, Stare: Mann Whitney U= 19.0, p=0.18), although these were not statistically significant. However, Ovx monkeys were significantly more likely than tubal-ligated monkeys to continue to freeze after the stranger left the room (Figure 4B). Indeed, three of the Ovx but none (zero) of the tubal-ligated monkeys continued to freeze after the stranger left the room in the Control 2 period. We grouped the animals into “responders” and “non-responders” to compare across the groups. Chi Square analysis revealed a significant difference between the groups with respect to this variable (Pearson’s Chi square = 4.29, df = 1, p = 0.04).

In the Novel Object tests (Figure 5), the animals were presented with a novel food (kiwi), a novel toy and a rubber snake in front of an apple slice. There was no difference between the groups in the latency to touch the kiwi (Log-Rank Chi square= 1.42, df=1, p=0.233). Nine of the subjects immediately (i.e., within 10 sec) explored the kiwi (average= 8.0 +/− 1.8 sec). On average, the monkeys spent over a quarter of the episode exploring (e.g., touching, manipulating) the kiwi fruit (average= 29.89 +/− 11.54 percent of time). There was no difference in the amount of time the Ovx and intact monkeys spent exploring the kiwi (Mann Whitney U= 12.0, p=0.92). Unlike the kiwi, few monkeys explored the brightly colored novel toy. None of the Ovx animals and only two of the intact touched the toy within the 5 min (300 sec) episode and thus we categorized the responses (Chi square= 2.50, df= 1, p=0.11). Interestingly, the two intact animals that did explore the object did so within 10 seconds. There was no difference between the groups in the time spent exploring the toy (Mann Whitney U= 10.5, p=0.64). The results differed with respect to the threatening novel object (rubber snake) with a piece of apple. Half of the monkeys came to the front of the cage and touched the snake, while the rest did not approach it, despite the presence of the apple. Because of this bimodal response, we categorized these behavioral responses for analysis. Intact animals were more likely than Ovx animals to touch the snake during the 5 min period (Chi square = 3.60, df= 1, p= 0.058). The Ovx animals that did touch the snake tended to take longer to do so compared to the intact animals (Log-Rank Chi square= 3.072, df=1, p=0.08). Interestingly, the Ovx group was more likely to appear to retreat with closed eyes during this period than the intact group (Chi square= 6.67, df= 1, p= 0.01). Four of the Ovx and none of the intact animals sat with closed eyes in the presence of the snake. The Ovx animals spent significantly less time exploring the snake during this episode than the intact monkeys (Mann Whitney U= 3.5, p=0.05).

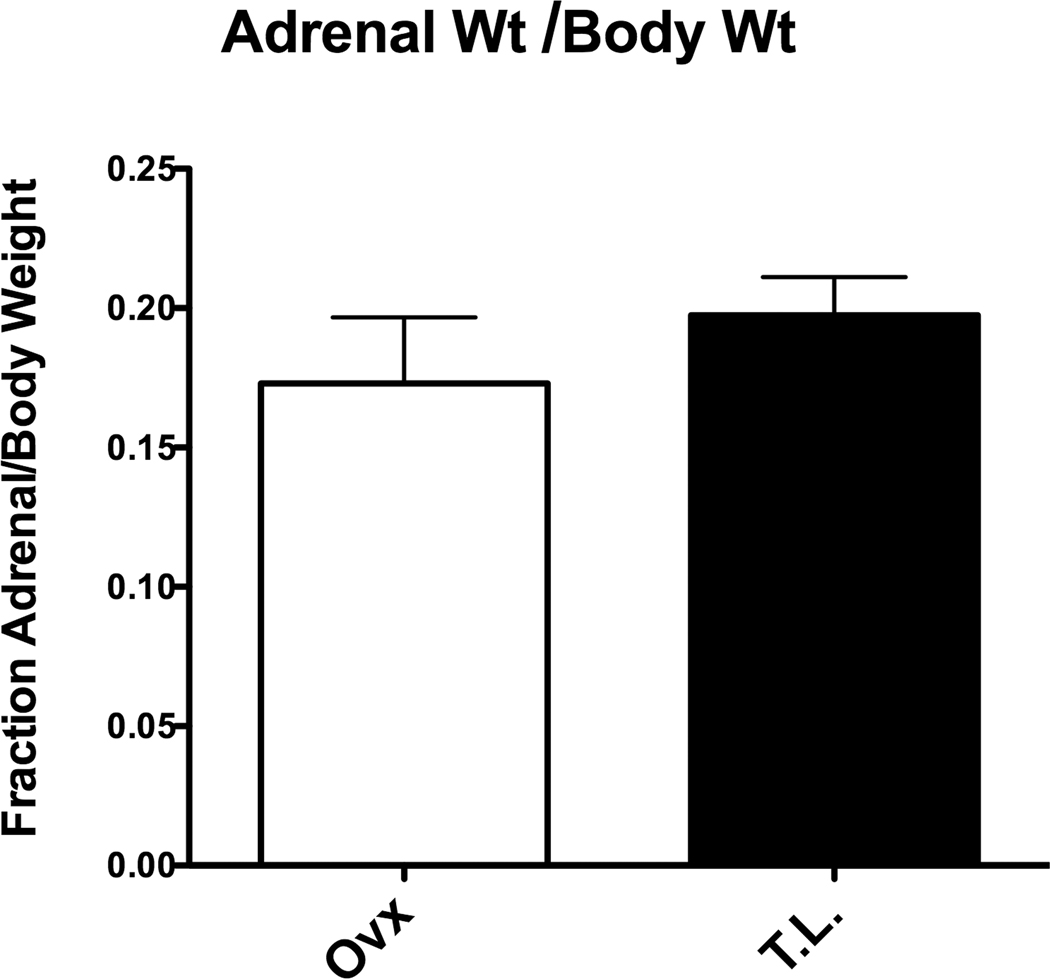

As shown in Figure 6, there was no difference in the adrenal weight/body weight ratio between the groups.

Figure 6.

Adrenal to body weight ratio in ovariectomized and tubal ligated Japanese macaques. Three years of ovariectomy had no effect on the adrenal to body weight ratio (two tailed t-test; t= 0.939, df=7, F= 2.38, p=0.37).

Discussion

This study examined behavioral responses to ovariectomy in monkeys living in a naturalistic, stable troop. This design allowed us to examine the effects of hormonal manipulation on individuals living in a natural setting, while maintaining a similar environment and diet. The effect of genetics on anxiety and depression is also currently of great interest. The ONPRC troop of Japanese macaques was established 45 years ago and no genetically distinct males have been added. Thus, the animals are highly related in general. Because of our interest in the serotonin system, we have examined polymorphisms in several serotonin-related genes from animals in the troop. Analysis of promoter polymorphisms in the genes coding for the serotonin reuptake transporter and TPH2 found no differences in males (unpublished). Hence, genetic differences between animals were minimal. The animals were also of similar rank across the matriarchal lineages and had similar social support (presence of close family members who intervene during conflicts). Moreover, the Ovx and tubal-ligated animals had similar adrenal/body weight ratios, suggesting that the groups were exposed to equal amounts of stress, or its lack [34]. Therefore, we postulate that differences in age, gender, environment, diet, prenatal health, genetics, rank, stress or social support were unlikely to contribute to the differences observed in behavior.

We were interested in manifestations of depression and anxiety. Depression per se is difficult to assess in free-ranging macaques. Indeed, studies demonstrating pharmacological-induced remission of depressive-like behaviors in macaques are lacking. Depressed juveniles show a decrease in social behavior, changes in eating, increases in distress vocalizations, changes in sleep, huddling and bradycardia [35]. Japanese macaque adults in the ONPRC troop do not emit distress vocalizations often (personal observation), so we could not use that as a measure. However, we could determine aspects of social behavior, sleep and eating. After three years, the Ovx monkeys spent less time in overall positive social behaviors (e.g., touch, groom, ventral contact), and thus more time alone, as compared to the intact monkeys. Interestingly, there were no differences between the groups with respect to specific behaviors, such as grooming, proximity, touching, or social play, rather the difference was only seen when these behaviors were taken together. This result was surprising, given that ovariectomy of cynomolgus macaques has been shown to increase grooming in small groups of females [36]. However, in the present study, the monkeys were in their natal group, which contained female relatives and other social support. Also of interest is our finding that the Ovx monkeys were groomed less than the intact monkeys, although there was no difference between the groups in the amount of time they spent grooming others. It is possible this could indicate a decreased dominance level of the Ovx animals. When grooming non-kin, female macaques often preferentially groom females of a higher dominance rank [37]. However, grooming with kin is often reciprocal. There was no difference in the number of close female family members between the Ovx and intact subjects, therefore the Ovx monkeys should have had the same opportunity to be groomed.

The Ovx monkeys initiated significantly less dominance behavior than intact animals during the third mating season. This is consistent with a study in group housed cynomolgus macaques that found estrogen administration increased aggression [36]. Further, Wallen and Tannebaum [38] reported, “increased sexual activity with the stimulus male disrupts social relationships between females. Thus, as females show increased and persistent affiliation with males at midcycle, they show decreased affiliation and increased agonism…. to females. One striking relationship is that as female agonism rapidly declines along with declining estradiol, female-female grooming increases”. The decreased dominance behavior in the Ovx females is consistent with these previous observations.

We did not see any differences in sleep behavior in the corral, however, we only examined the animals in the morning hours, and few animals sleep during this period. By year 3, the Ovx monkeys exhibited more consummatory behavior than intact monkeys, in both the birthing and mating season. Our observations are consistent with earlier studies showing that food intake decreased during the estrogen dominated phase of the menstrual cycle in rhesus monkeys, and that administration of exogenous extradiol inhibited food intake in a dose-related fashion [39]. Coupled with the increase in consumatory behavior, the Ovx monkeys exhibited a decrease in locomotor behavior compared to the tubal ligated females. Shively and colleagues suggested a cluster of behaviors that indicate depression in cynomolgus monkeys [40]. They found that increased depressive behaviors were strongly associated with a decrease in locomotion and that both were precipitated by a high fat diet. The cluster of behaviors observed in Ovx females that included increased object-play, increased eating and decreased locomotion are consistent with the observations of Shively and colleagues. Interestingly, the Ovx animals also spent more time in object play (e.g., manipulating various objects within the corral, playing on structures) than intact animals in the birthing season. It is possible that the Ovx monkeys were engaged in this behavior in lieu of spending time in social behaviors. Females in this troop often spend a great deal of time with the new mothers in the birthing season, particularly if they do not have their own infants (personal observation). It was interesting that the Ovx monkeys did not appear to engage in this behavior.

We also assessed behavioral indices of anxiety which include scratching, yawning and body shake. These behaviors are ameliorated by benzodiazepines indicating they are anxiety driven [6]. Further, previous studies have shown that estrogen administration to Ovx monkeys significantly decreased scratching [19]. We saw no yawning or body shake behavior, and very few instances of scratching in our corral observations. Ovariectomy did not have an effect on scratching in this study. This could be a consequence of the relatively low number of focal observations, or it could be that there was not a great deal of anxiety behavior manifested in the corral at the times in which we did our observations. This finding is not surprising. Individual differences in stress reactivity are often most prominent in times of moderate stress [41]. Life in the corral is relatively low stress, and therefore we would not necessarily expect to see a great deal of anxious behavior. Further, all monkeys had some degree of social support, which helps to mediate stressful situations.

Estradiol increases affiliative behavior and ovariectomy could be predicted to decrease affiliative behavior. By year 3, the females were 6 years old and old enough to actively participate in mating behavior. The Ovx group spent less time in consort behavior with males than the intact animals. This result is not surprising and has been previously observed in other studies [18, 42]. Female rhesus macaques initiate mating during the preovulatory surge of estradiol by carefully orchestrated and repeated movement toward a male [38]. Japanese macaques are similar to rhesus in this regard; hence the Ovx females initiated less consort behavior towards males.

With regard to grooming and social behavior, Wallen and Tannebaum discuss the role of female hormones on the social relationships and social structure of rhesus macaque society [38]. They reported that the midcycle surge of estradiol in the female drives female proximity to males, grooming of males and sexual activity, whereas grooming of females varies inversely with sexual activity. Agonism to other females increases around ovulation in a top down manner. In another study, introduction of males to ovariectomized females resulted in no social affiliation or integration for 2.5 years. When Ovx females were administered estrogen, they exhibited the first male grooming ever observed after 3 days [38]. Our Japanese macaque corral is significantly different from the context of other experiments in that the animals have close family members, especially their mothers and sisters, to groom at any time. Thus, ovariectomy did not significantly alter this basic interaction in the social context of relatives. Further, in this study, we were not able to determine the phase of the menstrual cycle in the intact animals. However, observations were taken over several weeks during the mating season. Therefore, the intact animals were likely to be in various stages of the menstrual cycle during that time period.

There were significant differences between Ovx and tubal ligated monkeys in the temperament tests at the end of year 3. We expected Ovx monkeys to display more anxious behavior in this test, including freezing in response to a human intruder, scratching, and vocalizations. None of the monkeys scratched or vocalized during the Human Intruder test. There was a trend for Ovx monkeys to freeze more than intact monkeys during the profile and stare, although it was not statistically significant. However, this is likely due to the small sample size and high degree of individual variation. Interestingly, the Ovx monkeys were more likely than intact animals to continue to freeze during the control period directly following the profile period, (i.e., Control 2 or C2). In this period, the human stranger is not in front of the monkey; therefore, any residual anxiety related behavior might be due to the monkey’s inability to quickly regulate its mood and reaction to the human stranger. We did not see any other differences in behaviors, again likely due to our relatively small sample size. There were differences between the groups in the novel object tests. While there were no differences with respect to time spent exploring the novel fruit or toy, the Ovx animals were less likely than tubal ligated monkeys to explore a threatening novel object (rubber snake). These data are consistent with reports of increased anxiety in peri- and postmenopausal women across cultures [4, 43–45]. Thus, we suspect that anxiety was ameliorated by social support in the corral. However, when the animals were kept alone and presented with various stress-inducing stimuli for temperament testing, the Ovx animals manifested higher levels of anxious behaviors. Interestingly, Ovx monkeys were more likely than intact monkeys to close their eyes in the presence of the snake. While we do not know if the monkeys were actually sleeping or just closing their eyes, it is not an adaptive behavioral response to a potentially threatening situation. Even if the monkeys did not view the snake as dangerous, they were still in a novel environment in which an unfamiliar human enters every few minutes. In our experience, most adult macaques show increased arousal and vigilance during this sort of testing paradigm (personal observation), not ‘avoidance’ type behavior.

Overall, we found that the ovariectomized animals spent less time in social behavior, less time in sexual behavior and more time in consummatory behavior in their home environment compared to the intact monkeys. They also showed more anxious behaviors in temperament tests. We previously reported that removal of endogenous ovarian hormones reduced serotonergic function [10]. Serotonin influences a wide range of neural systems from the autonomic nervous system to cognition. Therefore, a decrease in serotonin may have increased vulnerability to stress and anxiety in these monkeys. However, estrogen and progesterone act on other neural systems as well, and the systems that promote the female repertoire of consort behaviors or dominance behaviors are not fully defined. We hypothesize that social support from family may ameliorate some neural deficiencies in the Ovx monkeys in their home environment. The monkeys in this study were ovariectomized at puberty, so it took several years for some of the behaviors to manifest, like mating behavior or eating behavior. Thus, there was a developmental factor. Even so, the behaviors did eventually diverge within the context of social support from relatives in the matriarchal lineages. In the stress of isolation in a single cage, ovariectomy led to an increase in anxiety-like behavior as measured during temperament testing.

There are a few shortcomings in the present study. First, the number of animals that we were able to include was relatively small, which reduced the power in our analyses. There was a great deal of individual variation in behavior, as is true in human populations. Even though there were close to 300 individuals in the ONPRC Japanese macaque colony, the ages of individuals was highly stratified. There were only 12 females of the same age cohort when we began our study. Choosing females from the following year’s cohort would also have introduced variability as well as potentially jeopardizing the health of the colony. A second factor that may have impacted our study is that we took relatively few focal observations of the animals in the corrals. Had we taken additional observations in the corrals, we may have increased our chances of detecting behavioral differences between our groups, particularly for relatively uncommon behaviors such as scratching. Nonetheless, even with these limitations, these studies suggest that ovarian hormones increase stress resilience and enable females to successfully navigate their social situation. Studies on the function and morphology of underlying neurobiological systems are underway.

Highlights.

Three years of ovariectomy in Japanese macaques is approximately equal to 9 years in women.

Ovariectomized macaques exhibit alterations in social, nonsocial and sexual behavior.

Ovariectomized macaques exhibit an increase in some anxious behaviors.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the technicians of the Division of Animal Resources, including surgery personnel, for their help with all aspects of this study. This study was supported by NIH grants MH62677 to CLB and P51-RR000163 for the operation of ONPRC

Supported by: NIH grants MH62677 to CLB and P51-RR00163 for the operation of ONPRC

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Maki PM, Freeman EW, Greendale GA, Henderson VW, Newhouse PA, Schmidt PJ, et al. Summary of the National Institute on Aging-sponsored conference on depressive symptoms and cognitive complaints in the menopausal transition. Menopause. 17:815–822. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181d763d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heikkinen J, Vaheri R, Timonen U. A 10-year follow-up of postmenopausal women on long-term continuous combined hormone replacement therapy: Update of safety and quality-of-life findings. J Br Menopause Soc. 2006;12:115–125. doi: 10.1258/136218006778234093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conde DM, Pinto-Neto AM, Santos-Sa D, Costa-Paiva L, Martinez EZ. Factors associated with quality of life in a cohort of postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:441–446. doi: 10.1080/09513590600890306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tangen T, Mykletun A. Depression and anxiety through the climacteric period: an epidemiological study (HUNT-II) J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;29:125–131. doi: 10.1080/01674820701733945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozdemir S, Celik C, Gorkemli H, Kiyici A, Kaya B. Compared effects of surgical and natural menopause on climacteric symptoms, osteoporosis, and metabolic syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;106:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troisi A. Displacement activities as a behavioral measure of stress in nonhuman primates and human subjects. Stress. 2002;5:47–54. doi: 10.1080/102538902900012378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castles DL, Whiten A, Aureli F. Social anxiety, relationships and self-directed behaviour among wild female olive baboons. Anim Behav. 1999;58:1207–1215. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron JL, Bridges MW, Graham RE, Bench L, Berga SL, Matthews K. Basal heart rate predicts development of reproductive dysfunction in response to psychological stress. 80th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society. 1998:P1–P76. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herod SM, Bytheway J, Dolney R, Cameron JL. Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. Atlanta, GA: 2006. Female monkeys who are sensitive to stress-induced reproductive dysfunction show increases in certain forms of anxious behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bethea CL, Lu NZ, Gundlah C, Streicher JM. Diverse actions of ovarian steroids in the serotonin neural system. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2002;23:41–100. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarkson TB. Estrogen effects on arteries vary with stage of reproductive life and extent of subclinical atherosclerosis progression. Menopause. 2007;14:373–384. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31803c764d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith SY, Jolette J, Turner CH. Skeletal health: primate model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Am J Primatol. 2009;71:752–765. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cline JM. Assessing the mammary gland of nonhuman primates: effects of endogenous hormones and exogenous hormonal agents and growth factors. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2007;80:126–146. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hao J, Rapp PR, Leffler AE, et al. Estrogen alters spine number and morphology in prefrontal cortex of aged female rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2571–2578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3440-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zehr JL, Maestripieri D, Wallen K. Estradiol increases female sexual initiation independent of male responsiveness in rhesus monkeys. Horm Behav. 1998;33:95–103. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herndon JG, Umpierre DM, Turner JJ. Effects of two different patterns of estradiol replacement on the sexual behavior of rhesus monkeys. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:853–856. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shively CA, Kaplan JR, Adams MR. Effects of ovariectomy, social instability and social status on female Macaca fascicularis social behavior. Physiology & Behavior. 1986;36:1147–1153. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90492-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasmussen DR. Functional alterations in the social organization of bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata) induced by ovariectomy: an experimental analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1984;9:343–374. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(84)90043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pazol K, Wilson ME, Wallen K. Medroxyprogesterone acetate antagonizes the effects of estrogen treatment on social and sexual behavior in female macaques. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2998–3006. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mook D, Felger J, Graves F, Wallen K, Wilson ME. Tamoxifen fails to affect central serotonergic tone but increases indices of anxiety in female rhesus macaques. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bethea CL, Reddy AP, Tokuyama Y, Henderson JA, Lima FB. Protective actions of ovarian hormones in the serotonin system of macaques. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:212–238. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lima FB, Bethea CL. Ovarian steroids decrease DNA fragmentation in the serotonin neurons of non-injured rhesus macaques. Mol Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AWA. [Animal Welfare Act] 2002 Public Law (PL) 89–544, 1966, as amended (PL 91–579, PL 94–279, and PL 99–198). 7 USC 2131–2159, as amended (PL 107–171, May 2002) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eaton GG, Resko JA. Plasma testosterone and male dominance in a Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata) troop compared with repeated measures of testosterone in laboratory males. Horm Behav. 1974;5:251–259. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(74)90033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eaton GG, Worlein JM, Glick BB. Sex differences in Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata): effects of prenatal testosterone on juvenile social behavior. Horm Behav. 1990;24:270–283. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(90)90009-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maruhashi T. An ecological study of troop fissions of Japanese monkeys (Macaca fuscata yaku) on Yakushima Island, Japan. Primates. 1982;23:317–337. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altmann J. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour. 1974;49:227–267. doi: 10.1163/156853974x00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Defensive behaviors in infant rhesus monkeys: environmental cues and neurochemical regulation. Science. 1989;243:1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.2564702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson DE, Coleman K, Bacanu SA, Devlin BJ, Rogers J, Ryan ND, et al. Heritability of fearful-anxious endophenotypes in infant rhesus macaques: a preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:284–291. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman K, Dahl RE, Ryan ND, Cameron JL. Growth hormone response to growth hormone-releasing hormone and clonidine in young monkeys: correlation with behavioral characteristics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13:227–241. doi: 10.1089/104454603322572561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldwin DV, Suomi SJ. Reactions of infant monkeys to social and nonsocial stimuli. Folia Primatol (Basel) 1974;22:307–314. doi: 10.1159/000155632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heath-Lange S, Ha JC, Sackett GP. Behavioral measurement of temperament in male nursery-raised infant macaques and baboons. Am J Primatol. 1999;47:43–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1999)47:1<43::AID-AJP5>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Nonhuman primate models to study anxiety, emotion regulation, and psychopathology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1008:189–200. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganong WF, Hume DM. Absence of stress-induced and compensatory adrenal hypertrophy in dogs with hypothalamic lesions. Endocrinology. 1954;55:474–483. doi: 10.1210/endo-55-4-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reite M, Kaufman IC, Pauley JD, Stynes AJ. Depression in infant monkeys: physiological correlates. Psychosom Med. 1974;36:363–367. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shively CA, Wood CE, Register TC, Willard SL, Lees CJ, Chen H, et al. Hormone therapy effects on social behavior and activity levels of surgically postmenopausal cynomolgus monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schino G. Grooming competition and social rank among female primates: a meta-analysis. Anim Behav. 2001;62:265–271. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallen K, Tannenbaum PL. Hormonal modulation of sexual behavior and affiliation in rhesus monkeys. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;807:185–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kemnitz JW, Gibber JR, Lindsay KA, Eisele SG. Effects of ovarian hormones on eating behaviors, body weight, and glucoregulation in rhesus monkeys. Horm Behav. 1989;23:235–250. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(89)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shively CA, Register TC, Adams MR, Golden DL, Willard SL, Clarkson TB. Depressive behavior and coronary artery atherogenesis in adult female cynomolgus monkeys. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:637–645. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817eaf0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suomi SJ. Genetic and maternal contributions to individual differences in rhesus monkey biobehavioral development. In: Krasnagor NA, Blass EM, Hofer MA, Smotherman WP, editors. Perinatal development: A psychobiological perspective. Orlando: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 397–419. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michael RP, Herbert J, Welegalla J. Ovarian hormones and grooming behaviour in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) under laboratory conditions. J Endocrinol. 1966;36:263–279. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0360263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR, Kapoor S, Ferdousi T. The role of anxiety and hormonal changes in menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 2005;12:258–266. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000142440.49698.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Juang KD, Wang SJ, Lu SR, Lee SJ, Fuh JL. Hot flashes are associated with psychological symptoms of anxiety and depression in peri- and post- but not premenopausal women. Maturitas. 2005;52:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jarkova NB, Martenyi F, Masanauskaite D, Walls EL, Smetnik VP, Pavo I. Mood effect of raloxifene in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2002;42:71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]