Abstract

Major advances in understanding the pathogenesis of inherited metabolic disease caused by mitochondrial DNA mutations have yet to translate into treatments of proven efficacy. Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy is the most common mitochondrial DNA disorder causing irreversible blindness in young adult life. Anecdotal reports support the use of idebenone in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, but this has not been evaluated in a randomized controlled trial. We conducted a 24-week multi-centre double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 85 patients with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy due to m.3460G>A, m.11778G>A, and m.14484T>C or mitochondrial DNA mutations. The active drug was idebenone 900 mg/day. The primary end-point was the best recovery in visual acuity. The main secondary end-point was the change in best visual acuity. Other secondary end-points were changes in visual acuity of the best eye at baseline and changes in visual acuity for both eyes in each patient. Colour-contrast sensitivity and retinal nerve fibre layer thickness were measured in subgroups. Idebenone was safe and well tolerated. The primary end-point did not reach statistical significance in the intention to treat population. However, post hoc interaction analysis showed a different response to idebenone in patients with discordant visual acuities at baseline; in these patients, all secondary end-points were significantly different between the idebenone and placebo groups. This first randomized controlled trial in the mitochondrial disorder, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, provides evidence that patients with discordant visual acuities are the most likely to benefit from idebenone treatment, which is safe and well tolerated.

Keywords: LHON, idebenone, mitochondrial disease, mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, mitochondrial DNA, optic atrophy, optic neuropathy

Introduction

Inherited disorders of mitochondrial energy metabolism are a major cause of metabolic disease affecting more than 1/5000 of the population (Schaefer et al., 2004). Despite major advances in understanding the molecular basis of these disorders, treatment options are extremely limited.

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON; MIM 535000) is the most common mitochondrial disorder affecting more than 1:14 000 males (Man et al., 2003). It causes progressive irreversible blindness and has a dramatic impact on quality of life (Kirkman et al., 2009). Over 90% of European and North American patients harbour one of three pathogenic mutations of mitochondrial DNA (m.3460G>A, m.11778G>A, and m.14484T>C), which affect complex I (Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide–ubiquinone oxidoreductase) of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (Harding et al., 1995). These mutations lead to a defect of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) synthesis accompanied by increased production of oxygen-free radicals causing retinal ganglion cell dysfunction and loss (Baracca et al., 2005; Zanna et al., 2005). Although it can affect both genders at any age, LHON is typically prevalent among young adult males (median onset at 24 years) (Nikoskelainen et al., 1996). In the acute phase, patients describe a loss of colour vision in one eye followed by a painless subacute decrease in central visual acuity accompanied by an enlarging centrocaecal scotoma. The second eye usually follows a similar course within 3 months, and significant improvements in visual acuity are rare for m.11778A>G and m.3460A>G patients. In the chronic phase, patients usually have a bilateral visual deficit that is symmetrical and life-long. Most remain legally blind, are unable to drive a motor vehicle, and are unable to find employment (Newman et al., 1991; Riordan-Eva et al., 1995; Nikoskelainen et al., 1996).

Anecdotally, patients with LHON have reported improvements in vision following treatment with the short-chain synthetic benzoquinone idebenone [2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-(10-hydroxydecyl)-1,4-benzoquinone] (Mashima et al., 1992; Carelli et al., 1998). Idebenone is a potent antioxidant and inhibitor of lipid peroxidation, interacting with the mitochondrial electron transport chain and facilitating mitochondrial electron flux in by-passing complex I (Haefeli et al., 2011). However, therapeutic effects of idebenone in patients with LHON have only been reported in isolated case reports and in a small retrospective open-labelled study (Mashima et al., 1992; Cortelli et al., 1997; Carelli et al., 1998, 2001; Mashima et al., 2000; Barnils et al., 2007).

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

Eighty-five patients enrolled in a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (Rescue of Hereditary Optic Disease Outpatient Study, RHODOS; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00747487) in Munich, Germany (n = 44); Newcastle upon Tyne, England (n = 30); and Montreal, Canada (n = 11). Inclusion criteria were met if patients were between 14 and 64 years of age, harboured m.3460G>A, m.11778G>A, or m.14484T>C mitochondrial DNA mutations, described vision loss due to LHON within 5 years, did not take drugs of abuse, and were neither pregnant nor breastfeeding. The study had ethical and institutional review board approval. All patients gave written informed consent. The trial profile is summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Randomization and masking

Patients were randomly assigned following a centralized randomization procedure to receive idebenone (Catena® 150 mg, Santhera Pharmaceuticals) 900 mg/day (300 mg three times a day during meals) or placebo for 24 weeks in a 2:1 ratio. This dose was chosen because it had previously been shown to be well tolerated. Patients were stratified by disease history and mitochondrial DNA mutation. A computer-generated randomization list was created for each stratum (Clintrak) with blocks (block size: 6) containing idebenone and placebo allocations in the correct proportion but random order. Each patient was assigned the next available treatment for the appropriate stratum by an independent provider (BIOP). The study site was informed of the medication kit number to be dispensed to the patient, ensuring that the blinding was maintained. Details of the randomization procedure were defined in a Study Medication Assignment Guideline. Compliance was monitored by pill count and idebenone serum levels.

Treatment outcomes

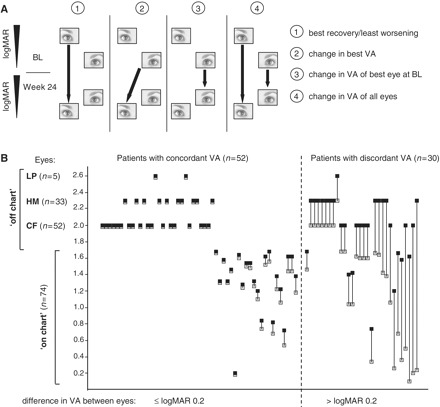

The main clinical efficacy analyses related to visual acuity are shown in Fig. 1A. The primary end-point was the best recovery of visual acuity between baseline and Week 24 determined with an Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study chart (van den Bosch and Wall, 1997). In patients with neither eye improving in visual acuity between baseline and Week 24, the change in visual acuity representing the least worsening was evaluated as best recovery. Patients only able to count fingers, detect hand motion or light perception were assigned logMAR values 2.0, 2.3 and 2.6, respectively (Lange et al., 2009). Change from baseline to Week 24 in best visual acuity was the pre-specified main secondary end-point. Other secondary end-points were the change in visual acuity of the best eye at baseline, and change in visual acuity for both eyes in each patient. Valid visual acuity data were available for 82 patients in the intent-to-treat population.

Figure 1.

(A) Visual acuity efficacy end-points (filled arrows) between baseline and Week 24. (1) Primary end-point—best recovery/least worsening in visual acuity, one value per patient. (2) Main secondary end-point—change in best visual acuity, one value per patient. (3) Pre-specified secondary end-point—change in visual acuity of best eye at baseline, one value per patient. (4) Pre-specified secondary end-point—change in visual acuity of all eyes (both eyes of a patient considered independent), two values per patient. (B) Visual acuity at baseline for all patients. Both eyes are shown for each subject, connected by a solid line (grey squares = eye with better visual acuity; black squares = eye with worse visual acuity). BL = baseline; CF = finger counting; HM = hand motion; LP = light perception; VA = visual acuity.

Pre-specified responder analyses involved the counting of patients and eyes that changed logMAR ≥ 0.2 (corresponding to ≥10 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study chart letters). Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness was assessed in 41 patients by optical coherence tomography (Barboni et al., 2005; Subei and Eggenberger, 2009). Thirty-nine patients in Munich were also assessed for colour contrast sensitivity by determining red–green (Protan) and blue–yellow (Tritan) colour confusion using computer graphics techniques (Arden and Wolf, 2004). All patients were assessed for Clinical Global Impression of Change (GCIC) determined on a 7-point scale from marked improvement (1) to marked deterioration (7) with no change representing a score of 4 (Guy, 1976).

Statistical analyses

Power calculations indicated that 84 patients would provide 80% statistical power to detect a difference of 0.2 (SD 0.3) logMAR between idebenone and placebo. Data were analysed using the mixed-model repeated measures method (Verbeke and Molenberghs, 2000). Treatment assignment, visit and interaction between the treatment assignment and visit, and pre-specified stratification factors (disease history and mitochondrial DNA mutation) were included as fixed factors, with baseline assessment as a covariate and subject as a random factor. The influence of additional factors (e.g. discordant visual acuities at baseline) was investigated by including the factor and interaction between the factor and treatment assignment to the mixed-model repeated measures model. The interaction terms were tested on a two-sided significance level of 0.10; otherwise a two-sided significance level of 0.05 was used. Authors had full and unrestricted access to the data and all co-authors contributed to the interpretation of the study.

Results

Baseline clinical data

The age, gender and mutation distribution were typical for Caucasian patients with LHON and were balanced between treatment groups (Table 1). Sixty-five per cent reported symptoms for >1 year, 85% had a logMAR ≥ 1.0 in both eyes (corresponding to legal blindness in many countries); and 37% had interocular acuity discordance of logMAR >0.2 (Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Idebenone 900 mg/day (n = 55)a | Placebo (n = 30)a | Total (n = 85)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD; [median] (range) (years) | 33.8 ± 14.8; [30.0] (14–63) | 33.6 ± 14.6; [28.5] (14–66) | 33.7 ± 14.6; [30.0] (14–66) |

| Sex | |||

| Male, n (%) | 47 (85.5) | 26 (86.7) | 73 (85.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 8 (14.5) | 4 (13.3) | 12 (14.1) |

| Mutations, n (%) | |||

| m.11778 G>A | 37 (67.3) | 20 (66.7) | 57 (67.1) |

| m. 14484 T>C | 11 (20) | 6 (20) | 17 (20.0) |

| m. 3460 G>A | 7 (12.7) | 4 (13.3) | 11 (12.9) |

| BMI, mean ± SD; [median] (range) (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 4.4; [23.5] (16.1–37.0) | 24.9 ± 4.4; [24.5] (18.9–35.1) | 24.5 ± 4.4; [23.6] (16.1–37.0) |

| Months since onset of vision loss, mean ± SD; [median] (range) | 22.8 ± 16.2; [17.8] (3–62) | 23.7 ± 16.4; [19.2] (2–57) | 23.1 ± 16.2; [18.2] (2–62) |

| Patients with onset of symptoms >1 year, n (%) | 36 (65.5) | 19 (63.3) | 55 (64.7) |

| Patients with logMAR ≥ 1.0,bn (%) one eye/both eyes | 5 (9.4)/45 (84.9) | 2 (6.9)/25 (86.2) | 7 (8.5)/70 (85.4) |

| Patients with logMAR <1.0 in both eyes,bn (%) | 3 (5.7) | 2 (6.9) | 5 (6.1) |

| Patients ‘off chart’,cn (%) one eye/both eyes | 11 (20.8)/25 (47.2) | 3 (10.3)/13 (44.8) | 14 (17.1)/38 (46.3) |

| Patients with discordant visual acuities,dn (%) | 20 (37.7) | 10 (34.5) | 30 (36.6) |

| LogMAR: mean ± SD,e (n) | |||

| Best eye | 1.61 ± 0.64 (53) | 1.57 ± 0.61 (29) | 1.59 ± 0.62 (82) |

| Worst eye | 1.89 ± 0.49 (53) | 1.79 ± 0.44 (29) | 1.86 ± 0.47 (82) |

| Both eyes | 1.75 ± 0.58 (106) | 1.68 ± 0.54 (58) | 1.73 ± 0.57 (164) |

a n = 82 (n = 53 for idebenone; n = 29 for placebo) for all visual acuity data.

blogMAR ≥ 1.0 in both eyes corresponds to legal blindness in most countries.

clogMAR > 1.68 (patients unable to read any letter on the chart).

ddefined as patients with difference in logMAR > 0.2 between both eyes.

eapplying logMAR 2.0 for counting fingers; logMAR 2.3 for hand motion; logMAR 2.6 for light perception.

BMI = body mass index.

Safety and tolerability

All 85 patients were evaluated for safety and tolerability. Compliance with study medication intake was high (mean pill count compliance of 96.5%, SD 6.8%). Seven patients prematurely discontinued treatment (n = 4 of 30 on placebo; n = 3 of 55 on idebenone), one discontinuation in each treatment group was related to adverse events. The nature, severity and frequency of the adverse events observed were indistinguishable between the study groups. Two serious adverse events were reported: a case of infected epidermal cyst (idebenone group) and one case of epistaxis (placebo group); both not considered to be due to the study medication. No clinically significant changes of vital signs and other biochemical or haematological parameters were observed.

Visual acuity

For the primary end-point (best recovery of visual acuity), the placebo group changed by logMAR −0.071 [95% confidence interval (95% CI): −0.176 to 0.034), while the idebenone group changed by logMAR −0.135 (95% CI: −0.216 to −0.054); the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance at 24 weeks (logMAR −0.064; 95% CI: −0.184 to 0.055; P = 0.291) (Fig. 2A). However, a trend towards improvement with idebenone was observed for the secondary end-points of change in best visual acuity (Idebenone: change in logMAR: −0.035; 95% CI: −0.126 to 0.055; Placebo: logMAR +0.085; 95% CI: −0.032 to 0.203; difference between groups: logMAR −0.120; 95% CI: −0.255, 0.014; P = 0.078) and the change in visual acuity of the best eye (Idebenone: change in logMAR: −0.030; 95% CI: −0.120 to 0.060; Placebo: logMAR +0.098; 95% CI: −0.020 to 0.215; difference between groups: logMAR −0.128; 95% CI: −0.262 to 0.006; P = 0.061) for the intent-to-treat population (Fig. 2C and E). When data from all eyes were combined, another pre-specified secondary end-point, there was a significant difference in the mean visual acuity between the idebenone and placebo group at 24 weeks (Idebenone: change in logMAR: −0.054; 95% CI: −0.114 to 0.005; Placebo: logMAR +0.046; 95% CI: −0.032 to 0.123; Difference between groups: logMAR −0.100; 95% CI: −0.188 to −0.012; P = 0.026; Fig. 2G). Excluding patients with the m.14484T>C mutation, which is known for its spontaneous recovery rate in visual acuity, led to a larger difference in the change of visual acuity between idebenone- and placebo-treated patients. Specifically, for the combined patients carrying m.11778G>A and m.3460G>A mutations, the point estimate between treatment groups for the primary end-point reached logMAR −0.092 (95% CI: −0.229 to 0.045; P = 0.187) and for the main secondary end-point, the change in best visual acuity, the point estimate was logMAR −0.169 (95% CI: −0.326 to −0.011; P = 0.037). All of the observed changes in visual acuity in the intent-to-treat population correlated with the patients’ clinical global impression of change (for best recovery in visual acuity: R = −0.32, P = 0.005; for change in best visual acuity: R = −0.34, P = 0.002; for change in visual acuity of the patient’s best eye: R = −0.33, P = 0.004 and for the change in visual acuity for all eyes: R = −0.32, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Change in visual acuity (logMAR) end-points over time for the change in best recovery of visual acuity (A and B), change in best visual acuity (C and D), change in visual acuity of the patients’ best eye at baseline (E and F) and change in visual acuity for all eyes (G and H). For each analysis two populations are presented: the whole study population (n = 82, intent-to-treat population for visual acuity end-points) (A, C, E and G) and subpopulation of patients with discordant visual acuities at baseline (n = 30, B, D, F and H). Filled squares/solid line = idebenone group; filled circles/dashed lines = placebo group, P-values for comparison between idebenone and placebo groups. Data are estimated means (±SEM) from mixed model for repeat measures based on the change from baseline. ITT = intent-to-treat; VA = visual acuity; W = weeks.

Given the observed trend, we performed a post hoc subanalysis of the patients with discordant visual acuities at baseline (i.e. patients with difference of logMAR >0.2 between eyes, Fig. 1A), based on the premise that this objectively defined group (n = 30) would include patients at the highest risk of further visual loss. A formal test of the interaction between the effect of idebenone and discordance of visual acuity at baseline was significant for all secondary end-points, indicating that the difference between idebenone and placebo groups was different among patients with discordant visual acuities versus patients with concordant visual acuity. The estimated mean difference among the patients with discordant visual acuities in best recovery in visual acuity between the idebenone and placebo group was logMAR = −0.285; 95% CI: −0.502 to −0.068; P = 0.011 (Fig. 2B) with similar results for the best visual acuity (difference between groups: logMAR = −0.421; 95% CI: −0.692 to −0.150; P = 0.003; Fig. 2D), change in visual acuity of the patient’s best eye (difference between groups: logMAR = −0.415; 95% CI: −0.686 to −0.144; P = 0.003; Fig. 2F), and when data for all eyes was combined (difference between groups: logMAR = −0.348; 95% CI: −0.519 to −0.176; P = 0.0001; Fig. 2H). In contrast, among the patients with concordant visual acuity, no significant differences were seen in any of the end-points: estimated difference between the idebenone and placebo group being logMAR +0.056 (95% CI: −0.091 to +0.202; P = 0.452) for best recovery in visual acuity; logMAR +0.037 (95% CI: −0.107 to +0.180; P = 0.613) for the best visual acuity; logMAR +0.022 (95% CI: −0.120 to +0.165; P = 0.757) for change in visual acuity of the patient’s best eye and logMAR +0.028 (95% CI: −0.070 to +0.125; P = 0.577) when data for all eyes was combined.

The trend towards improvement with idebenone was also apparent in a responder analysis (Table 2). For patients with discordant visual acuities at baseline, there was a 45% difference in the responders for the best recovery of visual acuity (P = 0.024); and a 32.5% difference in the end-point assessing the change in visual acuity for all eyes (P = 0.011). Of particular interest were the patients unable to read any letters on the chart at baseline (‘off-chart patients’). When all eyes were considered independently, 20% of the eyes of the patients receiving idebenone were able to read at least one full line on the chart at Week 24, while none of the patients in the placebo group showed this improvement (P = 0.008).

Table 2.

Responder analyses for change in visual acuity

| Population | Analysis | Idebenone (%) | Placebo (%) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intent-to-treat population (n = 82): proportion of patients with change of logMAR of 0.2 or more at Week 24b | Improvement: best recovery in visual acuity | 20/53 (37.7) | 7/29 (24.1) | 0.231 |

| Improvement: best visual acuity | 14/53 (26.4) | 5/29 (17.2) | 0.420 | |

| Improvement in visual acuity of all eyesc | 30/106 (28.3) | 10/58 (17.2) | 0.131 | |

| Worsening in visual acuity of all eyesc | 18/106 (17.0) | 17/58 (29.3) | 0.075 | |

| Subgroup of patients with discordant visual acuities at baseline (n = 30): proportion of patients with change of logMAR of 0.2 or more at Week 24b | Improvement: best recovery in visual acuity | 11/20 (55.0) | 1/10 (10.0) | 0.024 |

| Improvement: best visual acuity | 6/20 (30.0) | 0/10 (0.0) | 0.074 | |

| Improvement in visual acuity of all eyesc | 15/40 (37.5) | 1/20 (5.0) | 0.011 | |

| Worsening in visual acuity of all eyesc | 8/40 (20.0) | 9/20 (45.0) | 0.067 | |

| Intent-to-treat population: patients with logMAR ≤0.5 in at least one eye at baseline | Deteriorate to logMAR 1.0 or more | 0/6 (0) | 2/2 (100) | 0.036 |

| Subpopulation of patients who were off chart at baseline with both eyes | Could read at least five letters on the chart at Week 24 with at least one eye | 7/25 (28.0) | 0/13 (0.0) | 0.072 |

| Eyes that were off chart at baseline | Could read at least five letters on the chart at Week 24 | 12/61 (19.7) | 0/29 (0.0) | 0.008 |

a P-values calculated with Fisher’s exact test.

bPatients with premature discontinuation were classified as non-improvers.

cEyes considered independent.

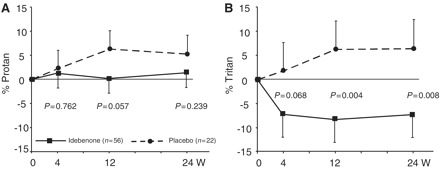

Colour contrast sensitivity

Most patients (92%) had abnormal colour contrast sensitivity at baseline in both protan and tritan domains in both eyes. There was a significant improvement in the tritan colour contrast in the idebenone group at 12 weeks (difference between groups: −14.51%; 95% CI: −24.19 to −4.83; P = 0.004) and 24 weeks (difference between groups: −13.63%; 95% CI: −23.61 to −3.66; P = 0.008) (Fig. 3). A similar trend was observed in the protan domain, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Change in colour contrast sensitivity for red–green (Protan; A) and blue–yellow (Tritan; B). Data are estimated mean changes from baseline (± SEM) from mixed model for repeat measures. Filled squares/solid lines = idebenone group; filled circles/dashed lines = placebo group.

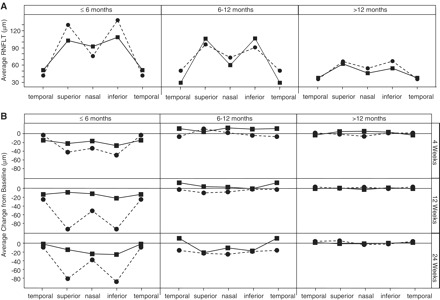

Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness

There was no difference in the pattern of retinal nerve fibre layer thickness at baseline for patients grouped by disease onset of ≤6 months, 6 months to 1 year, and >1 year (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the visual acuity data, there was a trend towards maintaining retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in the idebenone group in superior, nasal and inferior quadrants, among patients with ≤6 months disease history (Fig. 4B). Due to the small sample size, no formal statistical analysis was conducted.

Figure 4.

Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness at baseline for patients with disease onset of ≤6, 6–12 and >12 months (A). The mean retinal nerve fibre layer thickness for the temporal, superior, nasal and inferior retinal quadrants are shown. Relative change from baseline to Weeks 4, 12 and 24 in retinal nerve fibre layer thickness (B). n = 6/4 (idebenone/placebo) for eyes with disease onset of ≤6 months; n = 8/6 for eyes with disease onset of 6–12 months; n = 32/26 for eyes with disease onset of >12 months. Filled squares/solid line = idebenone group; filled circles/dashed line = placebo group. RNFLT = retinal nerve fibre layer thickness.

Discussion

Considerable advances in our understanding of the molecular and biochemical basis of mitochondrial DNA-associated diseases have not yet translated into treatments of proven efficacy. A major hurdle has been the inherent difficulties of conducting adequately-powered randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials for such rare genetic diseases. Recruitment often presents a major challenge, in part due to limited disease awareness among general hospital and community physicians. In addition, the lack of detailed natural history studies makes it difficult to select clinically meaningful trial end-points to inform a priori power calculations. Finally, patients often find the prospect of taking placebo unacceptable and self-medicate, using Internet-based suppliers of vitamins, food supplements and unapproved medication. All of these issues are relevant for LHON, limiting previous clinical investigations to underpowered, open-labelled studies (Mashima et al., 2000; Newman et al., 2005). Employing recently established patient registries in Germany (mitoNET) and the UK (MRC cohort), we were able to conduct the first adequately-powered randomized placebo-controlled trial for this disorder.

Although this study did not meet the primary end-point, all pre-specified secondary visual acuity end-points, subgroup, and responder analyses pointed towards a beneficial effect for idebenone, particularly for patients with discordant visual acuities between the two eyes. Although we chose best recovery in visual acuity as the primary end-point, both change in best visual acuity and change in visual acuity in both eyes are equally justifiable end-points from a clinical perspective, and arguably the change in best visual acuity is the most relevant to the patients’ needs—being the closest related to visual function in daily life.

Colour contrast sensitivity data provided an independent measurement of the potential treatment effects of idebenone. In agreement with previous studies (Grigsby et al., 1991; Ventura et al., 2007), we observed a high incidence of defects affecting both the red–green (protan) and blue–yellow (tritan) colour domains. LHON preferentially affects the smallest diameter optic nerve fibres in the parvocellular bundle that mediate protan colour vision (Grigsby et al., 1991; Ventura et al., 2007). The relative resistance of the larger stratified fibres mediating tritan vision through the koniocellular pathway may explain why we only observed an effect of idebenone in this domain. The natural history of retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in LHON (Barboni et al., 2005) reveals a complex biphasic pattern, where the value increases during the acute phase (due to retinal nerve fibre layer swelling), followed by a decrease as the patient enters the chronic phase (due to the resolution of retinal nerve fibre layer swelling and subsequent axonal loss). Subdividing patients into different subgroups based on the disease duration to account for the complex pattern in change of retinal nerve fibre layer thickness markedly reduced statistical power, explaining why the observed trend did not reach significance in patients ≤6 months since disease onset.

Although subgroup analysis should be interpreted with great caution, subdividing patients into those with and without discordant interocular visual acuities indicated that patients with discordant eyes had the largest treatment effect. It is notoriously difficult to subdivide patients with LHON into ‘acute’ and ‘chronic’ disease phases based solely on their recollection of symptom onset, since well-established cases can present only after the second eye becomes clinically involved (Riordan-Eva et al., 1995). In order to avoid this problem, we used a more objective categorization of patients into those with discordant and concordant visual acuities. This was based on the published literature where, in general, a visual acuity difference of logMAR >0.2 is considered uncommon in late-stage patients (Newman et al., 1991; Riordan-Eva et al., 1995), suggesting that asymmetric interocular visual acuities are more likely to be found among patients with a relatively recent onset of symptoms. However, in our study of patients with symptoms of <5 years duration, we saw no relationship between discordant visual acuities and the duration of reported symptoms. A much longer study will be required to determine whether the frequency of discordant visual acuities does correlate with disease duration, as suggested by the literature (Newman et al., 1991; Riordan-Eva et al., 1995), but this would not alter our main conclusions. Based on our findings, idebenone appeared to prevent further visual loss in patients with discordant visual acuities, in contrast, to the placebo group whose visual acuities continued to deteriorate during the 24 week study period. The clinical significance of this finding is that patients with discordant visual acuities may represent the patients with greatest potential reserve, and therefore the patients that have the most clinical benefit with regard to preventing further visual loss.

Analysis of the different mitochondrial DNA mutations was consistent with these findings. We saw the largest treatment effect among patients harbouring the m.11778G>A and m.3460G>A mutations. Among patients with the m.14484T>C mutation, the genotype that has been reported to confer a better prognosis of visual recovery, a high spontaneous recovery rate in the placebo group was recorded, effectively abolishing a treatment effect in these patients. It is important to note that there was no significant difference in the frequency of the m.14484T>C mutation between patients recruited with concordant and discordant visual acuities. Thus, based on these 6-month study data, idebenone appears to ameliorate the visual outcome particularly among patients with the m.11778G>A and m.3460G>A mutations, which account for ∼80% of all European and North American cases with LHON.

A key finding of this study was the minimal side-effect profile among patients with LHON treated with high-dose idebenone, which was not different to placebo, and contributed to the high compliance rates observed in this study. When combined with other published data, this indicates that at 900 mg/day, idebenone is safe and is well tolerated—a key factor in deciding whether or not this new treatment should be used in clinical practice.

Funding

Recruiting of patients was supported by use of patient databases; the German network for mitochondrial disorders (mitoNET, 01GM0862), which is funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, Bonn, Germany), and the UK Mitochondrial Disease Cohort, which is funded by the Medical Research Council (UK). T.K. is the coordinator of mitoNET, and also receives other funding from BMBF and from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). P.F.C. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow in Clinical Science and a UK National Institute of Health Senior Investigator who also receives funding from the Medical Research Council (UK), Parkinson’s UK, the Association Française contre les Myopathies, and the UK NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ageing and Age-related disease award to the Newcastle upon Tyne Foundation Hospitals NHS Trust. P.Y.W.M. is a UK Medical Research Council (UK) Clinical Research Fellow.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Sponsored by Santhera Pharmaceuticals, Liestal, Switzerland. D.P., G.M., C.R. and T.M. are regular employees of Santhera Pharmaceuticals. We thank J. Al-Tamami for excellent work as a study nurse, B. Büchner and G. Rudolph for support in patient investigations, W.T. Andrews for medical monitoring, G. Alvaro for analysis of safety data and N. Coppard for support in efficacy data analysis and interpretation. An independent data monitoring committee (iDMC) with four permanent/voting members with experience in clinical pharmacology and drug safety (L. Kappos, Basel; S. Krähenbühl, Basel; G. Wilmot, Atlanta) and statistics (C. Bernasconi, Basel) was assigned to the study. The iDMC met approximately every 6 months to review the safety data from the ongoing study and to advise the sponsor on the continuation or potential modification of the study. M.L. is an independent statistician contracted by Santhera Pharmaceuticals to carry out statistical analyses. We are indebted to the patients who volunteered for this study and we also thank all doctors who have transferred patients into this trial.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- LHON

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy

References

- Arden GB, Wolf JE. Colour vision testing as an aid to diagnosis and management of age related maculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1180–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.033480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baracca A, Solaini G, Sgarbi G, Lenaz G, Baruzzi A, Schapira AH, et al. Severe impairment of complex I-driven adenosine triphosphate synthesis in leber hereditary optic neuropathy cybrids. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:730–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barboni P, Savini G, Valentino ML, Montagna P, Cortelli P, De Negri AM, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer evaluation by optical coherence tomography in Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnils N, Mesa E, Munoz S, Ferrer-Artola A, Arruga J. Response to idebenone and multivitamin therapy in Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2007;82:377–80. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912007000600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli V, Barboni P, Zacchini A, Mancini R, Monari L, Cevoli S, et al. Leber's Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON) with 14484/ND6 mutation in a North African patient. J Neurol Sci. 1998;160:183–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli V, Valentino ML, Liguori R, Meletti S, Vetrugno R, Provini F, et al. Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON/11778) with myoclonus: report of two cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:813–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.6.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortelli P, Montagna P, Pierangeli G, Lodi R, Barboni P, Liguori R, et al. Clinical and brain bioenergetics imporvement with idebenone in a patient with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy: a clinical and 31P-MRS study. J Neurol Sci. 1997;148:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby SS, Vingrys AJ, Benes SC, King-Smith PE. Correlation of chromatic, spatial, and temporal sensitivity in optic nerve disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:3252–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. Clinical global impression. In: Guy W, editor. Assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare; 1976. pp. 125–6. [Google Scholar]

- Haefeli RH, Erb M, Gemperli AC, Robay D, Courdier Fruh I, Anklin C, et al. NQO1-Dependent redox cycling of idebenone: effects on cellular redox potential and energy levels. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding AE, Sweeney MG, Govan GG, Riordan-Eva P. Pedigree analysis in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy families with a pathogenic mtDNA mutation. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:77–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman MA, Korsten A, Leonhardt M, Dimitriadis K, De Coo IF, Klopstock T, et al. Quality of life in patients with leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3112–5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange C, Feltgen N, Junker B, Schulze-Bonsel K, Bach M. Resolving the clinical acuity categories "hand motion" and "counting fingers" using the Freiburg Visual Acuity Test (FrACT) Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:137–42. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man PY, Griffiths PG, Brown DT, Howell N, Turnbull DM, Chinnery PF. The epidemiology of leber hereditary optic neuropathy in the north East of England. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:333–9. doi: 10.1086/346066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashima Y, Hiida Y, Oguchi Y. Remission of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy with idebenone. Lancet. 1992;340:368–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91442-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashima Y, Kigasawa K, Wakakura M, Oguchi Y. Do idebenone and vitamin therapy shorten the time to achieve visual recovery in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy? J Neuroophthalmol. 2000;20:166–170. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200020030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman NJ, Biousse V, David R, Bhatti MT, Hamilton SR, Farris BK, et al. Prophylaxis for second eye involvement in leber hereditary optic neuropathy: an open-labeled, nonrandomized multicenter trial of topical brimonidine purite. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:407–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman NJ, Lott MT, Wallace DC. The clinical characteristics of pedigrees of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy with the 11 778 mutation. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1991;111:750–62. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76784-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoskelainen EK, Huoponen K, Juvonen V, Lamminen T, Nummelin K, Savontaus M-L. Ophthalmologic findings in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, with special reference to mtDNA mutations. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:540–14. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan-Eva P, Sanders MD, Govan GG, Sweeney MG, Da Costa J, Harding AE. The clinical features of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy defined by the presence of a pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutation. Brain. 1995;118:319–37. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer AM, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM, Chinnery PF. The epidemiology of mitochondrial disorders-past, present and future. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1659:115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subei AM, Eggenberger ER. Optical coherence tomography: another useful tool in a neuro-ophthalmologist's armamentarium. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20:462–6. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283313d4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch M, Wall M. Visual acuity scored by the letter-by-letter or probit methods has lower retest variability than the line assignment method. Eye. 1997;11:411–17. doi: 10.1038/eye.1997.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura DF, Gualtieri M, Oliveira AG, Costa MF, Quiros P, Sadun F, et al. Male prevalence of acquired color vision defects in asymptomatic carriers of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2362–70. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zanna C, Ghelli A, Porcelli AM, Martinuzzi A, Carelli V, Rugolo M. Caspase-independent death of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy cybrids is driven by energetic failure and mediated by AIF and Endonuclease G. Apoptosis. 2005;10:997–1007. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-0742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.