Abstract

A unique type of vernal pool are those formed on granite outcrops, as the substrate prevents percolation so that water accumulates in depressions when precipitation exceeds evaporation. The O2 dynamics of small, shallow vernal pools with dense populations of Isoetes australis were studied in situ, and the potential importance of the achlorophyllous leaf bases to underwater net photosynthesis (PN) and radial O2 loss to sediments is highlighted. O2 microelectrodes were used in situ to monitor pO2 in leaves, shallow sediments, and water in four vernal pools. The role of the achlorophyllous leaf bases in gas exchange was evaluated in laboratory studies of underwater PN, loss of tissue water, radial O2 loss, and light microscopy. Tissue and sediment pO2 showed large diurnal amplitudes and internal O2 was more similar to sediment pO2 than water pO2. In early afternoon, sediment pO2 was often higher than tissue pO2 and although sediment O2 declined substantially during the night, it did not become anoxic. The achlorophyllous leaf bases were 34% of the surface area of the shoots, and enhanced by 2.5-fold rates of underwater PN by the green portions, presumably by increasing the surface area for CO2 entry. In addition, these leaf bases would contribute to loss of O2 to the surrounding sediments. Numerous species of isoetids, seagrasses, and rosette-forming wetland plants have a large proportion of the leaf buried in sediments and this study indicates that the white achlorophyllous leaf bases may act as an important area of entry for CO2, or exit for O2, with the surrounding sediment.

Keywords: Aerenchyma, aquatic plant, CAM, malate, photorespiration, sediment O2, submergence tolerance, tissue O2, underwater photosynthesis, vernal rock pools, wetland plants

Introduction

Ephemeral wetlands are formed throughout the world during periods where precipitation exceeds evaporation, typically during winter and early spring. Some of these wetlands cycle on an annual basis between periods of standing water and a brief period of waterlogging followed by extreme desiccation, and have been termed ‘vernal pools’ in Mediterranean-type environments (Keeley and Zedler, 1998). A unique type of vernal pool are those formed on granite outcrops, as the granite forms an impervious substrate that prevents downward percolation so that even small depressions in the rock result in standing water. Granite rock pools are 100% precipitation fed, are often very shallow (<10 cm deep), and the substrate of weathered granite and debris blown in from the surrounding land is only a few centimetres thick, resulting in the waterlogged phase being very brief (Keeley and Zedler, 1998; Keeley, 1999). As a consequence, the aquatic flora and fauna of granite rock pools are highly specialized to cope with the extreme environment of these large annual changes. In the present study, in situ tissue O2 dynamics of completely submerged Isoetes australis, were examined and the role of the acholorophyllous leaf bases for gas exchange with the surrounding sediment evaluated.

During the submergence phase, the plants also need to cope with large diurnal fluctuations in temperature and dissolved O2 and CO2 that occur in these soft-water, shallow pools (Keeley and Zedler, 1998). At night, system respiration processes consume O2 and produce CO2, which can lead to hypoxia in the water column (<4 kPa O2), while CO2 builds up to concentrations 10- to 15-fold that of atmospheric equilibrium (Keeley and Busch, 1984). During the daytime, when photosynthesis prevails over system respiration, the shallow water column along with a relatively high plant biomass drive pH and O2 up while CO2 decreases to <1 μM (calculated from pH and alkalinity; Keeley and Busch, 1984). Underwater photosynthesis of the completely inundated vegetation is thus challenged by high afternoon temperatures and high O2 in combination with low CO2, a situation that promotes photorespiration (Pedersen et al., 2011). As a result, carbon-concentrating mechanisms such as C4 or CAM photosynthesis and bicarbonate use are common in plants inhabiting vernal pools (Keeley, 1999).

Although shallow and transient, vernal pools can host a wide array of aquatic flora and fauna and the Isoetes genus is commonly a major component of the vegetation (Keeley and Zedler, 1998). Species of Isoetes are lycopods at the same organizational level as ferns and all have hollow quill-like leaves arising from a central corm. Most, if not all, Isoetes species tested so far exhibit indicators of CAM photosynthesis such as dark fixation of CO2, overnight accumulation of malate followed by daytime decarboxylation, and large diurnal amplitudes in tissue acidity (Keeley, 1998b). However, CAM is often lost in specimens that develop functional stomata upon air exposure (Keeley et al., 1983). The CAM photosynthetic mechanism is of great advantage in the shallow pools as CO2 can be fixed during the night-time when it is readily available and subsequently released internally and used in daytime photosynthesis at a time when CO2 becomes depleted in the water (Keeley, 1998a, b, c). As an example, I. australis has recently been shown to possess CAM and in addition to increased underwater photosynthesis at low external CO2 concentrations, the CAM activity also greatly reduced apparent photorespiration at external O2 concentrations up to 2.2-fold that of atmospheric equilibrium (Pedersen et al., 2011).

Isoetes species belong to a polyphyletic group of plants of the isoetid life form; these use sediment-derived CO2 for underwater photosynthesis (Madsen et al., 2002). By using sediment-derived CO2, these plants tap into an alternative source of CO2 that is not readily available to plants that do not possess the isoetid growth form (Winkel and Borum, 2009). Isoetids have short, stiff leaves in a basal rosette with large gas-filled lacunae and mostly unbranched porous roots, facilitating diffusion of CO2 from the surrounding sediment into the roots and up to the leaves. The leaves are often covered with a thick cuticle (Sculthorpe, 1967) reducing the loss of CO2 to the surrounding water. Consequently, O2 produced in underwater photosynthesis is not lost to the surrounding water column but diffuses into the roots and out to the rhizosphere (Sand-Jensen and Prahl, 1982). As a consequence, the rhizosphere of isoetids is oxidized and free molecular O2 may even persist throughout a diurnal cycle (Pedersen et al., 1995; Sand-Jensen et al., 2005; Møller and Sand-Jensen, 2011).

The in situ O2 dynamics of small, shallow vernal pools with dense populations of I. australis were studied; a system contrasting markedly in depth of sediment and water column with those in which submerged plant O2 dynamics have previously been evaluated. With only a few centimetres of substrate of low organic matter content on top of bedrock, comparison of diurnal O2 dynamics in these systems with the lake and ocean situations in previous studies (Greve et al., 2003; Borum et al., 2005; Sand-Jensen et al., 2005; Møller and Sand-Jensen, 2011) is of interest. The shallow vernal pools probably dry up and refill a few to several times during spring and so I. australis faces periods of waterlogging or drained conditions with the leaves exposed to air and hence, underwater net photosynthesis (PN), CAM activity, and leaf morphology were compared in both aquatic (produced under water) and aerial (produced in air) leaves. It was observed that the white achlorophyllous leaf bases buried in the shallow sediment accounted for a large proportion of shoot tissue area, with green tips extending only ∼15 mm into the shallow water column. This observation prompted testing of the hypothesis that CO2 entry via these leaf bases might enhance underwater PN, and that these could also be sites of O2 loss to sediments. It was found that sediment O2 concentrations never differed significantly from intra-plant O2 concentrations, indicating easy O2 exchange between plants and sediment and the basal leaf portions enhanced underwater PN by the green tips, and presumably also contributing substantially to O2 loss to the sediment.

Materials and methods

Study site and plant materials

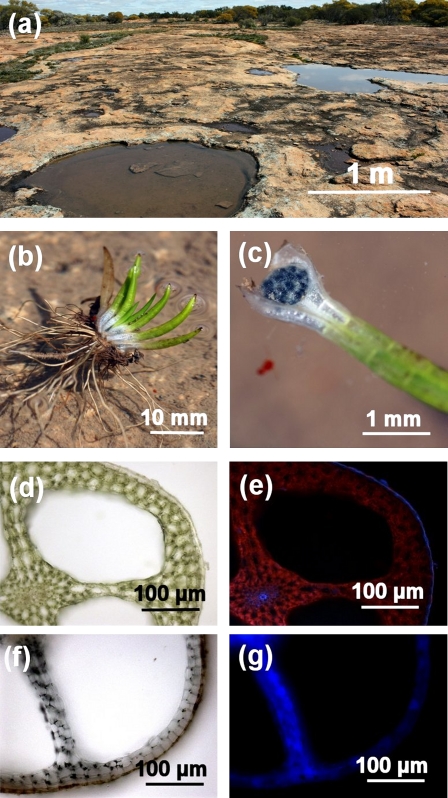

Granite outcrops with numerous shallow vernal pools near Mukinbudin, Western Australia (118.2896° E, 30.7468° S) were chosen as the site for all in situ studies and as a collection point for plants used in laboratory and anatomical studies (Fig. 1a). The vernal pools have dense populations of I. australis S. Williams (Fig. 1b) when the pools are water filled from July to October in most years, depending on rainfall (Tuckett et al., 2010). Plants for laboratory work were collected as intact turfs in 5 l buckets and transported back to a 15/20 °C night/day phytotron facility at the University of Western Australia.

Fig. 1.

Habitat of I. australis (a), uprooted specimen (b), leaf with sporangium (c), and transverse hand-cut sections of the green tips (d, e) and white bases (f, g) of leaves. Each granite outcrop supports numerous shallow pools that typically fill and evaporate throughout the winter and early spring (June to October), and then completely dry out in late spring/early summer, depending on rainfall patterns. Some pools host dense populations (>5000 plants m−2, see Fig. 3) of I. australis. Each plant typically had 6–10 leaves (b) with a white base (achlorophyllous) supporting the sporangium (c) and green tips (chlorophyllous). Cross-section micrographs of the leaves under bright field illumination (d, e) and ultraviolet light excitation, resulting in red chlorophyll autofluorescence (e, g), illustrate that in the green tips most cells contained chlorophyll (except the epidermal cells and those in the vascular bundles) and a well-developed cuticle (e), whereas there was no chlorophyll autofluorescence and no indication of a cuticle in the white bases (g).

In the phytotron, plants were maintained in submerged cultures, 3–5 cm below the surface of ‘artificial floodwater’ (defined below) that was topped up with deionized water to replace evaporation. In one experiment, previously fully submerged plants were de-submerged and maintained in waterlogged sediment, with shoots in air, for 5 weeks. Leaves formed in air were compared with those of plants in a continuously submerged treatment. The artificial floodwater was a solution made in deionized water with final electrical conductivity (EC) of 85 μS cm−1 and containing (in mol m−3): 0.15 Ca2+, 0.10 Mg2+, 0.10 K+, 0.30 Cl–, 0.10 SO42–, and 0.10 HCO3–. This low-EC solution was designed to simulate the water in the temporary vernal pools on the granite outcrops from which the specimens were collected. In the phytotron, I. australis continued to grow with a leaf turnover rate of about one leaf per week. Seedlings of the genera Glossostigma and Crassula were removed weekly in order to keep I. australis as a monoculture. Leaf tissues were used for up to 6 weeks following turf collection.

Plant O2 dynamics in situ

Intra-plant O2 dynamics in leaves of I. australis were followed in situ for plants growing in the vernal rockpools. Two three-channel underwater pA meters with built-in data loggers (PA3000UP-OP; Unisense, Aarhus, Denmark) and 50 μm tip diameter O2 microelectrodes (OX50-UW; Unisense, Aarhus, Denmark) were used. Micromanipulators with microelectrodes were mounted on aluminium stands fixed to a block of concrete, and the microelectrodes were positioned using a magnifying glass and then changes in signal were used to detect the surface of leaves following the procedure of Pedersen et al. (2006). Oxygen microelectrodes were inserted ∼200 μm into the leaves, 50–75 μm after a constant signal in the gas-filled lacunae was detected. Four replicate measurements were taken in individuals growing in separate vernal pools but located within 25 m of one another (Fig. 1). Sediment pO2 was measured using a sturdy O2 minielectrode (OX500; Unisense, Aarhus, Denmark) inserted 10 mm into the sediment next to a plant; a control measurement in bare sediment was also taken and showed that sediment without plants (35 cm to nearest I. australis population) was anoxic (data not shown). Water column pO2 was also measured using a sturdy O2 minielectrode (OX500) mounted just above the canopy ∼3–4 cm below the water surface.

Key environmental parameters were measured in the vernal rockpools during the period of in situ O2 measurements. Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) and temperature were logged using pendant loggers (Hobo Pendant Temp/Light Data Logger UA-001-08; Onset Computer Corporation, Pocasset, MA, USA). Water pH was measured every hour using a handheld pH meter (RH-203; Radiometer, Brønshøj, Denmark). Available CO2 was calculated using the alkalinity, temperature, and pH data and the formulae of Mackereth et al. (1978). Data were recorded from midday, including throughout the dark period, until the following midday.

Underwater PN

Underwater PN by leaves was measured using the method described in Pedersen et al. (2011). Leaf tips (5–10 mm), without the achlorophyllous white base (hereafter referred to as green tips), were excised, the cut end sealed with paraffin, and placed in glass vials (10 ml) with stoppers. Each vial contained two leaf tips in incubation medium, and two glass beads for mixing as these rotated on a wheel within an illuminated water bath (20 °C). PAR inside the submerged glass vials, was 350 μmol m−2 s−1 (measured using a 4π US-SQS/L; Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). To evaluate the importance of the white achlorophyllous bases of the leaves for gas exchange (CO2 uptake and O2 loss), leaves with the white base present and the cut end sealed with paraffin were also incubated in flasks and PN rates compared with those of the green tips.

The incubation medium was the same composition as the artificial floodwater (see above) but with 75 μM KHCO3, 2.5 mol m−3 MES with pH adjusted to 6.00 using KOH to achieve 50 μM free CO2 in the solution. The dissolved O2 concentration in the incubation medium was set at 50% of air equilibrium, by bubbling with 1:1 volumes of N2 and air (prior to the addition of KHCO3); this avoided excess build-up of O2 during the measurements. As vials were incubated in light immediately after adding the leaves, and since these produce O2 when in light, there was no risk of tissue hypoxia. Vials without leaves served as blanks.

Following incubations of known duration (60–75 min), dissolved O2 concentrations in the vials were measured using a Clark-type O2 microelectrode (Revsbech, 1989; OX-25;, Unisense A/S, Aarhus, Denmark), connected to a pA meter (PA2000; Unisense A/S, Aarhus, Denmark). The electrode was calibrated immediately prior to use.

Projected areas of leaf samples were measured using a leaf area meter (LI-3000; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). Projected areas were converted into actual surface areas using an empirical relationship obtained from measurements of areas based on leaf diameter and length of the cylindrical leaves and conical tips. The ratio of actual area to projected area=3.633; n=10, see Pedersen et al. (2011) for details.

ROL from green leaf tips and white achlorophyllous bases

Radial O2 loss (ROL) was measured from green and white portions of individual cylindrical leaves to determine resistance to diffusion across cell layers exterior to the lacunae. Leaves were excised and then the tip (∼3–4 mm) of each leaf was excised, so as to provide a direct path to the lacunae and this end was inserted into a conical plastic holder connected to a tube (internal diameter 5 mm, length 60 mm) open to the atmosphere. The holder with leaf inserted was mounted using putty (BlueTac; Bostick, Wauwatsa, WI, USA) in a Perspex tank (length 200 mm), containing deoxygenated stagnant 0.1% w/v agar solution also containing: K+, Cl− (5.0 mol m−3) and Ca2+, SO42− (0.5 mol m−3). The tube enabled internal O2 to be manipulated, by connecting the tube to a reservoir either of air (21.6% O2) or air enriched with O2 (30% O2). ROL from four replicate leaves was measured at two positions, one each in the green and white achlorophyllous regions, and each at both internal O2 concentrations, using cylindrical O2 electrodes (internal diameter 2.25 mm, height 5.0 mm) fitted with guides to keep each cylindrical leaf near the centre of each electrode (Armstrong and Wright, 1975; Armstrong et al., 1994). Internal O2 concentrations in the green and achlorophyllous regions in four other replicate leaves held in the same set-up were measured using O2 microelectrodes (see above). Diameter of each leaf was measured at the centre of each ROL position, using digital callipers, and the proportion of the outer cell layers (i.e. exterior to the lacunae) to the radius within each tissue zone was determined from hand-cut cross-sections (across all four lacunae, in four replicate leaves). Surface area was calculated assuming that the tissue within the electrode was cylindrical. Resistance to O2 movement across the cell layers external to the lacunae was calculated according to the equations in Garthwaite et al. (2008).

Evaporation from leaf surfaces

Evaporation of water vapour was used as a proxy for cuticle resistance as these surfaces lack stomata, assuming that resistance to water vapour loss might reflect also resistance to movement of other gases (e.g. O2 and CO2). Evaporation from green tips of aquatic leaves (leaves produced under water) and aerial leaves (leaves produced in air; see above) was compared, for tips excised and with the cut surface sealed with paraffin. The experiment was conducted in a desiccator containing desiccant (silica gel) and evaporation was followed over time by weighing groups of five leaf tips initially every 15 min and then every hour. Evaporation rates were calculated as loss in mass over time assuming a density of water of 1 kg l−1. Using the same procedures, evaporation from green aquatic leaf tips was also compared with that from white leaf bases of aquatic leaves. Data were fitted to an exponential loss function (GraphPad Prism 5.0).

Sediment characteristics and sediment O2 consumption

From each vernal pool, three sediment cores (diameter 7.1 cm) were collected in the same area where the in situ O2 measurements took place. Plants were counted to provide a density measurement and shoots, corms, and roots were separated and oven-dried at 70 °C. Another three cores were taken from each site to measure sediment organic matter as ‘loss on ignition’ (5 h at 550 °C).

The potential biological O2 demand (BOD) of the sediment was measured by incubating 1 ml of fresh sediment in 40-ml vials in the dark in artificial floodwater initially at air equilibrium (see underwater PN for chemical composition). Sediment samples were first pre-incubated for 12 h in 5 ml of water bubbled with air to eliminate chemical O2 demand (Raun et al., 2010). The vials were then filled with air-bubbled artificial floodwater, closed, and incubated at 20 °C in the dark on a rotating wheel for 1–1.5 h. O2 concentrations were measured before and after incubation using an O2 minielectrode (OX500; Unisense, Aarhus, Denmark). BOD was calculated as O2 consumption per sediment volume and unit time (nmol O2 l−1 s−1).

Anatomy

Transverse sections were cut, using a hand-held razor, from leaves of field collected plants. Sections were viewed with a light microscope (Zeiss Axioskop2; Carl Zeiss Pty Ltd, Germany), with chloroplast visualization augmented by ultraviolet (UV) light, which causes red chlorophyll autofluorescence. Images were captured with a digital camera (Zeiss AxioCam MRc Rev.3; Carl Zeiss Pty Ltd, Germany) and manipulated for light levels, contrast and brightness using a software package (AxioVision Rel. 4.6; Carl Zeiss Pty Ltd, Germany).

Data analysis

GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for one- or two-way ANOVA (with Tukey or Bonferoni post hoc test) and Student's t-test to compare means. If needed, data were log-transformed to improve normality and fulfil requirements of homogeneous variance. GraphPad Prism was also used to fit data sets to predictive models (one-phase exponential decay) in experiments with evaporation.

Results

In situ O2 dynamics and vernal pool characteristics

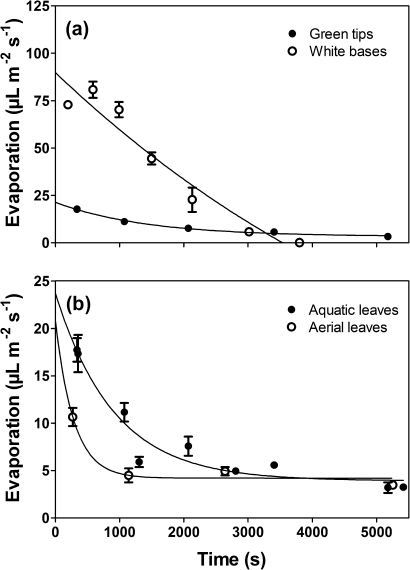

I. australis grows with a large portion of each leaf (i.e. leaf bases) buried within the sediment, with this buried portion appearing to lack pigmentation (Fig. 1b, c). Leaves of plants collected from vernal pools in Mukinbudin showed pigmentation only in the upper ∼71% of their length (Table 1). Aside from the difference in pigmentation, the green and white leaf portions look superficially similar, being cylindrical—although the tips of the green portion then become conical in shape to form a pointy end. Both segments contain four large lacunae; however, some aspects of the anatomy of the sections differed between the green and white portions. The green portions contain chlorophyll (red autofluorescence, Fig. 1e) whereas the white bases are achlorophyllous (Fig. 1g) and neither the green tips nor the white bases form stomata. The green portions have a thicker cortical layer (∼3.4±0.3 cells; mean ±SE, n=5) compared with the white bases (∼2.2±0.3 cells; mean ±SE, n=5), which is also evident from the significantly higher contribution green tips make to the total dry mass. The water contents of the two sections were similar (Table 1). The cuticle was evident on the green tips, but not the white bases (Fig. 1e, g) suggesting a very thin or absent cuticle in these basal portions. This thinner cuticle is presumably more permeable as indicated by the initial 3.6-fold greater rate of loss of water vapour from the white bases as compared with the green tips (Fig. 6a).

Table 1.

Proportions, tissue water content, internal leaf lacunal O2 concentration, and rates of radial O2 loss from green tips and white achlorophyllous bases of I. australis leaves

| Leaf tissue type |

||

| Green tips | White bases | |

| Proportion of total leaf length (%) n=3 | 70.9±3.5a | 29.1±0.4b |

| Proportion of total DM (%) n=3 | 64.2±3.1a | 35.8±3.1b |

| Proportion of total FM (%) n=3 | 48.7±1.7a | 51.3±1.7a |

| Water content (%) n=3 | 90.6±0.8a | 95.1±0.1b |

| Leaf lacuna O2 concentration (kPa) n=4 (green tip cut and exposed to 20.6 kPa O2) | 20.3 ±0.2a | 15.9 ±1.8b |

| Radial O2 loss (nmol m−2 s−1) n=4 (green tip cut and exposed to 20.6 kPa O2) | 442.3 ±66.6a | 527.2 ±47.6a |

Proportions are given of total leaf length, total dry mass (DM), and total fresh mass (FM). Tissue water content of the two portions of leaves is also given. Letters indicate significant differences (Student's t-test; P<0.05).

Fig. 6.

Evaporation from green tips or white bases (a) and from green tips of either aquatic leaves or aerial leaves (b) of I. australis. Leaf segments were cut from leaves produced under water or in air and cut surfaces were sealed with paraffin before loss of fresh mass was followed over time. Evaporation from the white achlorophyllous tissues was initially 3.6-fold higher than from green tips (a), and evaporation from aquatic leaves was also higher than from leaves formed in air (b). Means ±SE, n=5.

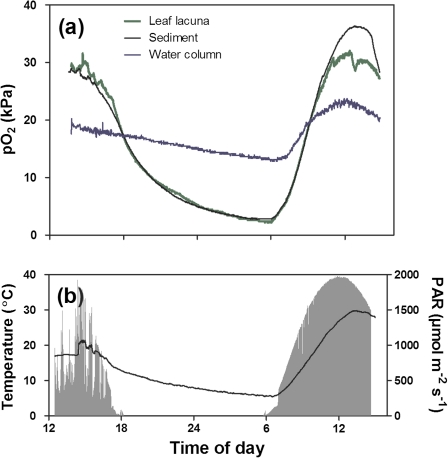

In situ O2 dynamics of the leaf lacunae of I. australis, the sediment, and the overlying water were obtained from four different vernal pools in close proximity to each other (<25 m) over three consecutive days early in October 2009, springtime in the study region. Measurements using O2 microelectrodes showed that pO2 in leaf lacunae and the sediment closely resembled each other both in daylight and during the night (Fig. 2a, Table 2). Figure 2 shows a typical trace of pO2 in leaf lacunae, sediment, and the overlying water, and in this example O2 in the lacunae was slightly above that of the surrounding sediment on the first day with maximum values of 30 kPa. In the late afternoon, pO2 in leaf lacunae and sediment declined rapidly, continuing to decline throughout the night, reaching values as low as 1.6 kPa by dawn (Table 2). The overlying water column also declined overnight but to a lesser extent than the leaf lacunae and sediments. Upon sunrise the next day, pO2 increased in both leaf lacunae and sediment to values similar to those of the day before, although pO2 in the sediment on day 2 was higher than in the leaf lacunae. This pattern was consistent in all four replicates and minimum or maximum intra-plant pO2 never significantly differed from the surrounding sediment either during the day or during the night (Table 2). The water column always had higher minimum night-time pO2 than the sediment and the plant tissues, but lower maximum values during the day (Table 2). Although the pO2 in both sediment and leaf lacunae declined throughout the night to ∼3 kPa in three replicates, however, in two replicates, leaf lacunae became severely hypoxic with pO2 down to 0.3 kPa (Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online).

Fig. 2.

In situ O2 dynamics in a leaf of I. australis, the sediment of the rhizosphere, and the water column (a), and incident light and temperature (b) over a diurnal cycle in a granite vernal pool. O2 microelectrodes were inserted into a lacuna of a fully expanded leaf, into the sediment (10 mm depth), and at canopy height in the water column. Water column CO2 concentrations fluctuated conversely to the intra-plant pO2; maximum dawn CO2 concentration was 270 μmol l−1 while minimum late afternoon CO2 concentration could be as low as 3 μmol l−1 based on pH, alkalinity, and temperature (calculated according to the approach in Stumm and Morgan, 1996).

Table 2.

In situ minimum and maximum O2 partial pressures (pO2) in leaf lacunae of I. australis, vegetated sediments, and overlying water column

| Component |

|||

| Leaf lacunae (kPa) | Sediment (kPa) | Water column (kPa) | |

| Minimum pO2 (mean ±SE) n=3 | 1.6±0.7a | 2.3±0.4a | 11.3±1.0b |

| Maximum pO2 (mean ±SE) n=6 | 30.9 ±1.1a | 32.9 ±2.0a | 21.3±1.5b |

O2 microelectrodes were inserted into a leaf lacuna of a fully expanded leaf, into the sediment (10 mm depth), and at canopy height in the water column. Measurements in non-vegetated sediments always showed values below the detection limit (<0.1 kPa). Letters indicate significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey post hoc; P<0.05) and n=3 minimum dark values or 6 for maximum day values as maximum values from the first and second days were included.

Day 1 in the example shown in Fig. 2 was a cloudy and windy day and water column temperature fluctuated by ∼20 °C. During the following calm and clear night, water temperature dropped to 5.5 °C and iced formed on top of some of the shallowest vernal pools without plants. Only 6 h after the minimum water temperature was recorded, a maximum of 30 °C was recorded the next day (sunny) in the same pool (Fig. 2b).

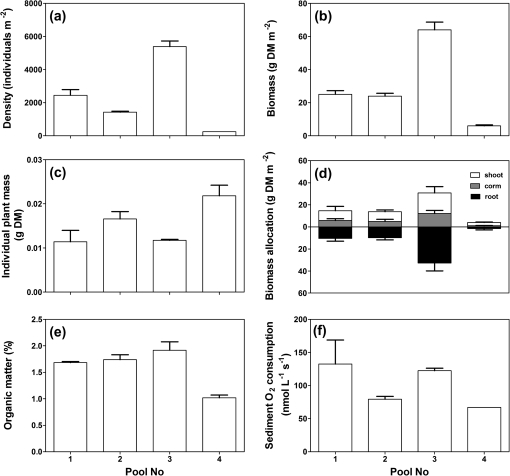

Plant density of I. australis was relatively uniform within vernal pools, but varied by >20-fold among vernal pools (250–5400 plants m−2; Fig. 3a). The variation in density among pools was also reflected in differences in biomass (6–64 g DM m−2; Fig. 3b) and hence, individual plant mass was not affected by plant density (Fig. 3c). Allocation into root biomass, corm, and shoot was similar for plants among vernal pools (Fig. 3d), potentially explaining why in situ O2 dynamics were remarkably similar in all four pools tested (Supplementary Fig. 1S available at JXB online).

Fig. 3.

Variation in plant density (a), individual plant mass (b), biomass allocation to shoot, corm, and root (c), biomass (d), sediment organic matter (e), and sediment O2 consumption (f) in four granite vernal pools inhabited by I. australis. Means ±SE, n=4.

Sediment organic matter was measured as there is a strong, often linear, relationship between sediment organic matter and sediment O2 consumption (Raun et al., 2010). Sediment organic matter varied little between the four vernal pools where the in situ O2 dynamics were measured (vernal pool Nos 1–4; Fig. 3e), but the sediment O2 consumption was variable among vernal pools and also within each pool (Fig. 3f).

Underwater PN and O2 exchange via the achlorophyllous leaf bases

Isoetids, including species of Isoetes, are known to lose a considerable share of the O2 produced in underwater PN via the roots as the leaves are often less permeable to gases than the roots (Sand-Jensen and Prahl, 1982). It was noticed that most specimens had a substantial proportion of the lower portions of leaves buried in the sediment and the buried leaf bases did not contain chloroplasts and had a less obvious cuticle (Fig. 1b, c, f, g). Thus, it was hypothesized that the white bases of leaves could be areas of entry for CO2 and thus enhance underwater PN, as well as contribute to radial O2 loss to the surrounding sediments.

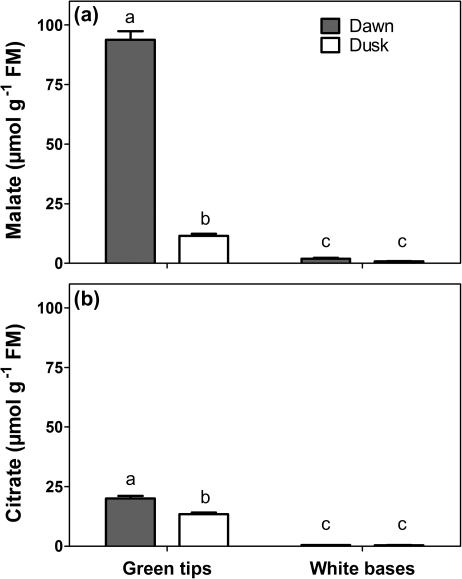

The achlorophyllous leaf bases contained very little malate [<2 μmol g−1 fresh mass (FM)] and citrate (<0.5 μmol g−1 FM) and neither varied significantly over the diurnal cycle. In contrast, the diurnal amplitude of malate in green leaf tips was 82 μmol g−1 FM while that of citrate was 7 μmol g−1 FM (Fig. 4a, b). Thus, the white bases do not contribute to night-time storage of organic acids that can be decarboxylated during the subsequent day.

Fig. 4.

Malate (a) and citrate (b) concentrations in green tips and white bases measured at dawn or dusk in leaves of I. australis. Means ±SE, n=3, and letters indicate significant differences (Student's t-test; P<0.05).

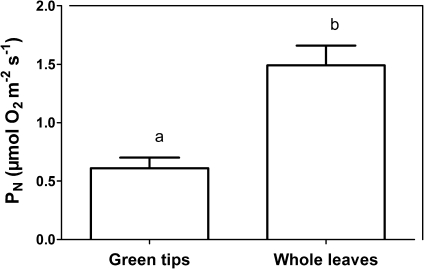

It seems, however, that the white bases could act as entry point for CO2, exit point for O2, or both. Whole excised leaves with the white bases present and sealed at the cut surface with paraffin had a 2.5 higher underwater PN compared with green leaf tips where the white base had been removed (cut surface also sealed), demonstrating that CO2 entry via the white bases can greatly enhance underwater PN (Fig. 5). This effect of enhanced CO2 entry with white bases intact probably resulted from the 1.5-fold larger surface area with these present, compared with the green tissues only.

Fig. 5.

Underwater PN in green tips and whole leaves of I. australis. Entire leaves or apical green leaf tips, in both cases with the cut surface sealed with paraffin, were incubated in glass vials attached to a rotating wheel within a water bath at 20 °C and PN was measured as O2 evolution during 60 min of incubation. PN is expressed per area of green tissue for green tips as well as for whole leaves. Means ±SE, n=5, and letters indicate significant differences (Student's t-test; P<0.05).

Measurements of ROL from the white base and green areas of leaves, when in darkness in an O2-free medium but with O2 supplied to the lacunae via a tube connected to air (20.6%) and then O2-enriched air (30%), provided rates of ROL as well as enabling calculation of the resistance to O2 loss across the external cell layers within the two zones. Although internal O2 concentrations were significantly lower in the lacunae of the white tissues (Table 1), the actual ROL rates did not differ significantly (442 nmol m−2 s−1 for green tips and 527 nmol m−2 s−1 for white bases). The rates show potential for ROL from white portions when an O2 gradient exists to the sediment. The mean resistance of the external cell layers to radial O2 diffusion did not differ between the two zones, and was 3.08×105 s cm−3. Differences in resistance to O2 loss within the two tissue areas were expected, as white bases initially lost water vapour 3.6-fold more compared with green tips (cut ends sealed in both cases, Fig. 6a) and microscopy of leaf cross-sections revealed a prominent cuticle on the green tips but this feature was not apparent on the white bases (Fig. 1e, g); so the cuticle is presumably not the major component of resistance to ROL from the lacunae within these shoots.

In summary, measurements of underwater PN , radial O2 loss, evaporation from tissue segments exposed to dry air, and microscopy, all support the hypothesis that the white leaf bases may enhance the surface area available for entry of CO2 and exit of O2 (both depending upon diffusion gradients with the external medium), in I. australis.

Do leaves acclimate to air exposure when the water level recedes?

In its natural habitat, I. australis probably faces highly fluctuating water regimes throughout the growth season. The brown tips (Fig. 1b) probably indicate that these leaves had been air exposed at some point during their life, so it was decided to investigate whether air-acclimated leaves are formed when shoots are in air during times with only sediment waterlogging. Aerial leaves, i.e. leaves formed in air, did show slower evaporation rates compared with aquatic leaves (leaves formed under water; Fig. 6b) indicating that the cuticle is somewhat modified when leaves are formed in air. However, underwater PN was similar in aerial and aquatic leaves, stomata never formed in aerial leaves, and the CAM activity was also maintained in aerial leaves (Pedersen et al., 2011).

Discussion

The present study evaluated diurnal in situ O2 dynamics in completely submerged I. australis, in the sediment in the shallow vernal pools in which the plants were growing, and in the overlying water column. It was found that sediment O2 concentrations were closely related to intra-plant O2 fluctuations and the resulting diurnal amplitude was 3-fold higher in the sediment than in the water column. In the following, the implications of these findings and possible role of the achlorophyllous basal leaf portions in O2 and CO2 exchange with the surrounding sediment are discussed.

There are few studies of in situ O2 dynamics in completely submerged wetland plants. Those of seagrasses all show that intra-plant O2 during the day is a function of light, whereas during the night O2 diffuses into leaves from the surrounding water column, and then into rhizomes and roots as the bulk sediment is permanently anoxic (Greve et al., 2003; Borum et al., 2005; Holmer et al., 2009). Borum et al. (2006) also showed that the dependence on water column for night-time O2 supply is critical; if the water column becomes hypoxic during the night, the risk of tissue anoxia is high. There are only two studies of in situ O2 dynamics in an isoetid (Lobelia dortmanna). A winter investigation showed that the rhizosphere remained oxic during the night and at one point was even slightly super-saturated during the day (Sand-Jensen et al., 2005). As these measurements were taken during winter, the low temperature (∼2 °C) probably resulted in very low microbial respiration and so low sediment O2 consumption. In contrast, a more recent study by Møller and Sand-Jensen (2011) showed that the same L. dortmanna population experiences anoxic conditions in the sediment during the summer with much higher temperatures (∼20 °C).

The present study on I. australis from shallow, vernal pools differs in one crucial aspect from previous in situ studies of O2 dynamics. In the vernal pools the sediment is restricted by the underlying biologically inert bedrock; consequently, these pools have a finite volume of sediment with a finite O2 consumption. This situation contrasts with lakes and oceans where the sediment represents an infinite volume, and thus also O2 consumption, ultimately leading to anoxia at certain distances into the sediment (i.e from the O2 source). In vernal pools with a dense population of I. australis, O2 builds up to >30 kPa during the day and even with the combined O2 uptake of respiration by plant roots and sediment microbes sediment anoxia did not occur during the night-time in regions near plants (Fig. 2, Table 2). In contrast, bare sediments remained anoxic both in light and dark, further emphasizing the importance of plant-derived inputs of O2 to enable sediments to remain oxic. Interestingly, shortly after sunset, the O2 gradient changes so that the leaves possibly take up O2 from the water column, which subsequently diffuses through the lacunae in leaves and roots and via ROL acts as a constant source of O2 to the sediment throughout the night. The oxic sediment conditions are not caused by an extremely low sediment O2 consumption per volume of sediment. In fact, the sediment O2 consumption rates in this study (70–130 nmol O2 l−1 s−1, Fig. 3) were similar to those reported by Raun et al. (2010), who found 114–173 nmol O2 l−1 s−1 with 0.9–1.7% organic matter, and considerably higher than those from the oligotrophic lake Skånes Värsjö with only 26 nmol O2 l−1 s−1 (Claus Møller, unpublished data). Hence, the oxic sediment must be caused by the fact that the O2 consumption is limited by the finite sediment volume, which in turn is likely to be approximately equal to the entire rhizosphere from which O2 is leaking during the day in pools with dense I. australis.

Interestingly, sediment pO2 at some points during the day exceeded that of intra-plant pO2, a phenomenon observed in all four replicate pools (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). This could be due to (i) O2 produced by microalgae on the sediment surface, (ii) O2 produced by neighbouring plants with higher rates of underwater PN and thus higher ROL, or (iii) the experimental circumstances. Natural sediments normally host a population of benthic microalgae and their photosynthesis can lead to super-saturation of O2 of up to 90 kPa in dense nutrient-rich biofilms (Lassen et al., 1997) but also up to 35 kPa on very nutrient-poor sediments with L. dortmanna (Pedersen et al., 1995; Møller and Sand-Jensen, 2011). Vertical O2 profiles of the sediments in the vernal pools were not measured. However, benthic algae were observed in most vernal pools in the granite outcrops and their O2 production would contribute to the supersaturation of the sediment (Lassen et al., 1997) and could, therefore, also result in sediment pO2 exceeding that of the lacunae inside I. australis. Secondly, the high external pO2 in the surrounding sediment could also be caused by high radial O2 loss from neighbouring plant roots. If the neighbouring plants had higher rates of photosynthesis, it would also lead to higher internal pO2 and ultimately to higher ROL and high local O2 concentration in the rhizosphere of some plants. Thirdly, in order to insert the microelectrodes into the small leaves, individuals might have been selected from patches with lower plant density than those nearby from where the sediment measurements were taken. It is not possible to exclude either of the three explanations and a combination of the three seems likely to have caused the high pO2 observed in the sediments containing I. australis.

The diurnal amplitudes in pO2 of the overlying water column were significantly smaller than in the sediments (Table 2) but resembled those observed for Californian vernal pools (Keeley and Busch, 1984). The water column of the Californian vernal pools, however, became lower in night-time pO2 presumably as a consequence of higher plant biomass in those pools, which are probably not quite as oligotrophic as the vernal pools of Western Australia that are formed on the granite outcrops. Diurnal CO2 fluctuations in the present study were, however, in the range reported from Californian vernal pools (Keeley and Busch, 1984) with very low values in the late afternoon (3 μmol l−1; air equilibrium is ∼15 μmol l−1) and high concentrations following night-time system respiration (270 μmol l−1, caption of Fig. 2). Water column temperature rose 20 °C in <6 h and the combination of high temperature, high pO2, and low CO2 would potentially increase photorespiration (Pedersen et al., 2011).

Most, if not all, species of Isoetes would often have a large proportion of the leaf tissue buried in the sediment, resulting in white acholorophyllous leaf bases. An extreme example is that of Isoetes andicola, a bog plant from the Andes, where only 4% of the total plant mass is allocated to green leaf tips whereas 11% of the total plant mass is in white acholorophyllous leaf bases (Keeley et al., 1994). In the present study of I. australis, the cuticle was less obvious in the white acholorophyllous leaf bases and these tissues were also more permeable to water vapour loss. However, the resistance of the outer cell layers to radial O2 diffusion did not differ between the white and green leaf portions, so the importance for gas exchange (CO2 entry from sediments, ROL to sediments) of the white acholorophyllous leaf bases could primarily be due to the larger surface area these provide. The mean resistance of the external cell layers to ROL in leaves of I. australis of 3.08×105 s cm−3 shows, as would be expected, that these shoot tissues have greater resistance to O2 movement than root tips (1.08×105 s cm−3), but substantially less resistance than mature root regions with a barrier to ROL (25.4×105 s cm−3) (roots of Hordeum marinum; Garthwaite et al., 2008). These measurements of ROL for the white bases demonstrate the potential for ROL when these tissues are in anoxic medium with a strong O2 sink. This situation would not occur adjacent to green tissue in floodwaters (usually not anoxic) but could occur for the white tissues buried in the sediment (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). The shoot bases are close to the O2 source and thus have relatively high internal O2 concentrations in the large lacunae (Table 1, Fig. 2), so ROL rates would be expected to be higher that those from the root tips, which are more distant from the O2 source and thus with lower internal O2 concentrations. In fact, the measured rates of ROL from the white portions are <2-fold lower than those obtained for highly gas-permeable roots of the isoetid L. dortmanna (∼800 nmol m−2 s−1; Møller and Sand-Jensen, 2008). It could be speculated that such an extension of the root system could have consequence not only for CO2 uptake and O2 loss but also for nutrient uptake since the cuticle is greatly reduced in the white basal part of the leaves. Considering that many aquatic species, including most seagrasses, with leaves emerging from underground meristems, possess white acholorophyllous leaf bases, these findings could have wider implications for our understanding of gas exchange with the upper rhizosphere of submerged plants.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Fig. S1 shows in situ O2 dynamics in a leaf of I. australis, the sediment of the rhizosphere and the water column and incident light and temperature (days 1–2) over a diurnal cycle in three granite vernal pools.

Acknowledgments

Dion Nichol's help to obtain permission to survey and work with vernal pools on Allan and Craig Nichol's property near Mukinbudin is greatly appreciated. The authors thank Dr Gregory Robert Cawthray for help with HPLC analyses of organic acids and Prof. William Armstrong for help with calculations of resistances to O2 diffusion derived from our ROL measurements. The financial support of CLEAR, a Villum Kann Rasmussen Centre of Excellence and the Danish Science Council is also acknowledged.

References

- Armstrong W, Strange ME, Cringle S, Beckett PM. Microelectrode and modeling study of oxygen distribution in roots. Annals of Botany. 1994;74:287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong W, Wright EJ. Radial oxygen loss from roots - theoretical basis for manipulation of flux data obtained by cylindrical platinum-electrode technique. Physiologia Plantarum. 1975;35:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Borum J, Pedersen O, Greve TM, Frankovich TA, Zieman JC, Fourqurean JW, Madden CJ. The potential role of plant oxygen and sulphide dynamics in die-off events of the tropical seagrass, Thalassia testudinum. Journal of Ecology. 2005;93:148–158. [Google Scholar]

- Borum J, Sand-Jensen K, Binzer T, Pedersen O, Greve TM. Oxygen movements in seagrasses. In: Larkum AWD, Orth JR, Duarte CM, editors. Seagrass biology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2006. pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite AJ, Armstrong W, Colmer TD. Assessment of O2 diffusivity across the barrier to radial O2 loss in adventitious roots of Hordeum marinum. New Phytologist. 2008;179:405–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve TM, Borum J, Pedersen O. Meristematic oxygen variability in eelgrass (Zostera marina) Limnology and Oceanography. 2003;48:210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Holmer M, Pedersen O, Krause-Jensen D, Olesen B, Petersen MH, Schopmeyer S, Koch M, Lomstein BA, Jensen HS. Sulfide intrusion in the tropical seagrasses Thalassia testudinum and Syringodium filiforme. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science. 2009;85:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE. C-4 photosynthetic modifications in the evolutionary transition from land to water in aquatic grasses. Oecologia. 1998a;116:85–97. doi: 10.1007/s004420050566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE. CAM photosynthesis in submerged aquatic plants. Botanical Review. 1998b;64:121–175. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE. Diel acid fluctuations in C-4 amphibious grasses. Photosynthetica. 1998c;35:273–277. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE. Photosynthetic pathway diversity in a seasonal pool community. Functional Ecology. 1999;13:106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE, Busch G. Carbon assimilation characteristics of the aquatic CAM plant, Isoetes howellii. Plant Physiology. 1984;76:525–530. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.2.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE, Mathews RP, Walker CM. Diurnal acid metabolism in Isoetes howellii from a temporary pool and a permanent lake. American Journal of Botany. 1983;70:854–857. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE, DeMason DA, Gonzalez R, Markham KR. Sediment-based carbon nutrition in tropical alpine Isoetes. In: Rundel PW, Smith AP, Meinzer FC, editors. Tropical alpine environments: plant form and function. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1994. pp. 167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE, Zedler PH. Characterization and global distributionof vernal pools. In: Witham CW, Bauder ETD, Belk D, Ferren WR, Ornduff R, editors. Conservation and management of vernal pool ecosystems: proceedings from a 1996 conference. Sacramento: California Native Plant Society; 1998. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lassen C, Revsbech NP, Pedersen O. Macrophyte development and resuspension events control microbenthic photosynthesis and growth. Hydrobiologia. 1997;350:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mackereth FJH, Heron J, Talling JF. Water analysis: some revised methods for limnologists. Ambleside, Cumbria: Freshwater Biological Association Publishers, 1978;36:120. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen TV, Olesen B, Bagger J. Carbon acquisition and carbon dynamics by aquatic isoetids. Aquatic Botany. 2002;73:351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Møller CL, Sand-Jensen K. Iron plaques improve the oxygen supply to root meristems of the freshwater plant, Lobelia dortmanna. New Phytologist. 2008;179:848–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller CL, Sand-Jensen K. High sensitivity of Lobelia dortmanna to sediment oxygen depletion following organic enrichment. New Phytologist. 2011;190:320–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen O, Andersen T, Ikejima K, Hossain MZ, Andersen FO. A multidisciplinary approach to understanding the recent and historical occurrence of the freshwater plant, Littorella uniflora. Freshwater Biology. 2006;51:865–877. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen O, Rich SM, Pulido C, Cawthray GR, Colmer TD. Crassulacean acid metabolism enhances underwater photosynthesis and diminishes photorespiration in the aquatic plant Isoetes australis. New Phytologist. 2011;190:332–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen O, Sand-Jensen K, Revsbech NP. Diel pulses of O2 and CO2 in sandy lake sediments inhabited by Lobelia dortmanna. Ecology. 1995;76:1536–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Raun AL, Borum J, Sand-Jensen K. Influence of sediment organic enrichment and water alkalinity on growth of aquatic isoetid and elodeid plants. Freshwater Biology. 2010;55:1891–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Sand-Jensen K, Borum J, Binzer T. Oxygen stress and reduced growth of Lobelia dortmanna in sandy lake sediments subject to organic enrichment. Freshwater Biology. 2005;50:1034–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Sand-Jensen K, Prahl C. Oxygen exchange with the lacunae and across leaves and roots of the submerged vascular macrophyte, Lobelia dortmanna l. New Phytologist. 1982;91:103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sculthorpe CD. The biology of aquatic vascular plants. London: Hodder & Stoughton; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Stumm W, Morgan JJ. Aquatic chemistry. 3rd edn. New York, USA: John Wiley and Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tuckett RE, Merritt DJ, Hay FR, Hopper SD, Dixon KW. Dormancy, germination and seed bank storage: a study in support of ex situ conservation of macrophytes of southwest Australian temporary pools. Freshwater Biology. 2010;55:1118–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Winkel A, Borum J. Use of sediment CO2 by submersed rooted plants. Annals of Botany. 2009;103:1015–1023. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.