Abstract

Interferon regulatory factors constitute a family of transcriptional activators and repressors involved in a large number of vital cellular processes. Interferon regulatory factor-3 (IRF-3) has been implicated in virus and double-stranded RNA mediated induction of IFNβ and RANTES, in DNA damage signaling, and in virus-induced apoptosis. With its critical role in these pathways, the activity of IRF-3 is tightly regulated in myriad ways. Here we describe novel regulation of IRF-3 at the level of RNA splicing. We show that an unprecedented dual utilization of a splice acceptor/donor site within the IRF-3 mRNA governs the production of two alternative splice isoforms.

Keywords: IRF-3, splicing, SR proteins

The interferon regulatory factor (IRF) family of proteins includes transcriptional activators and repressors involved in a large number of cellular responses. The pathways governed by IRFs include cellular growth control, resistance to bacterial infection, commitment to transformation by oncoproteins, T and B cell development, response to DNA damage, apoptosis, and response to virus infection (for reviews, see Nguyen et al. 1997; Harada et al. 1998; Mamane et al. 1999). One IRF family member, IRF-3, has mainly been implicated in the virus and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) mediated induction of IFNβ and RANTES (Lin et al. 1998; Navarro et al. 1998; Wathelet et al. 1998; Weaver et al. 1998; Yoneyama et al. 1998; Lin et al. 1999). However, recent work from a number of laboratories has led to identification of novel roles of IRF-3 in DNA damage response and virus-induced apoptosis (Heylbroeck et al 1999; Kim et al 1999), suggesting that IRF-3 is involved in a large number of diverse cellular pathways.

Much of what is known about the regulation of IRF-3 stems from the work on virus-induced IFNβ production. The regulation of the individual transcription factors, which bind the IFNβ promoter, occurs at multiple levels. For example, two transactivators, NFκB and IRF-3, reside mainly in the cell cytoplasm and are shuttled to the nucleus after virus infection (Baeuerle and Baltimore 1996; Lin et al. 1998; Wathelet et al. 1998; Weaver et al. 1998; Yoneyama et al. 1998). The timing and duration of a response to virus infection are likely controlled by the availability of transactivators. IRF-3 is rapidly degraded after virus infection, thereby providing an efficient mechanism for down-modulation of the IFNβ promoter (Lin et al. 1998; Ronco et al. 1998).

Another mechanism for controlling the availability and activity of transcription factors has gained attention (for review, see Lopez 1995). Alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs has the unique ability to generate a great structural and, consequently, functional diversity of isoforms, thus providing an opportunity to ensure even more finely tuned and lasting effects on gene expression than those offered by posttranslational modifications.

Here we describe an alternative splice isoform encoded by the IRF-3 gene, which we have called IRF-3a. IRF-3a is expressed ubiquitously in all tissues and cell lines tested, with variable ratios of IRF-3a to IRF-3 mRNA. We show that the organization of the alternative splice sites in the IRF-3 gene is novel and differs from patterns documented previously. We show that sequences downstream from the unusual splice junction are capable of binding members of the SR protein family, which can affect splice site selection.

Results

Cloning and characterization of the IRF-3a splice form

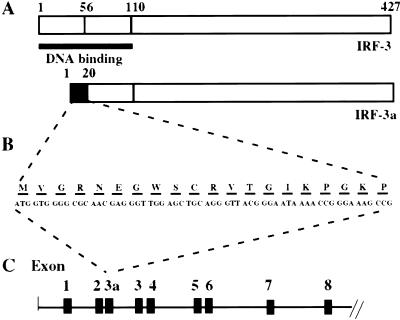

In the course of our analysis of IRF-3 and the cDNA that encoded it, we identified an alternative cDNA that encodes an isoform, which we have called IRF-3a. In IRF-3a, the 55 amino acid N terminus of IRF-3 has been substituted by a distinct 20-amino-acid domain that supplants one-half of the DNA binding domain found in IRF-3 (Fig. 1A). Figure 1B provides the cDNA and amino acid sequence of the novel portion of IRF-3a. To confirm that the IRF-3a-specific sequence was derived from an exon contained within the IRF-3 gene, a human genomic library was screened with a probe representing the first 500 base pairs of the IRF-3a cDNA. Five recombinant phage were purified to homogeneity. Two of these clones were analyzed, and the region near the junction of the presumed IRF-3a exon was amplified by PCR and sequenced. This analysis revealed that the IRF-3a-specific 20 amino acids were encoded by a single exon (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

IRF-3a unique N-terminal sequence and genomic organization. (A) Schematic representation of the IRF-3 and IRF-3a proteins. Black box designates the novel 20 amino acids encoded by IRF-3a-specific exon. (B) Novel nucleotide and amino acid sequence comprising IRF-3 unique region. (C) Intron–exon borders for IRF-3 gene designated by Lowther and coworkers (1999). The IRF-3a-specific exon is positioned between exons designated 2 and 3.

Lowther and coworkers (1999) have recently published the genomic organization of human IRF-3. After further analysis of a human genomic clone, the IRF-3a-specific sequence was localized between exons 2 and 3 of their published designation (Figs. 1C,3A below). The IRF-3a-specific initiation ATG codon maps 172 base pairs downstream from the end of exon 2, whereas the 5′ end of exon 3a maps right at the junction with exon 2 (see below). The exon encoding the IRF-3a-specific sequence is designated 3a (Figs. 1C,3A below).

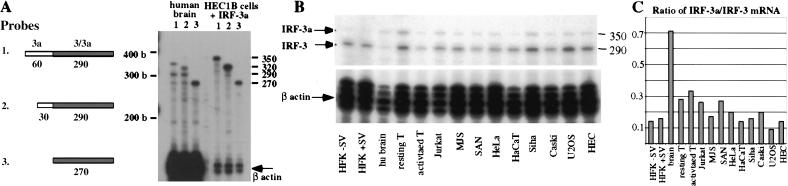

IRF-3a and IRF-3 are ubiquitously expressed

To determine the relative patterns of expression of IRF-3 and IRF-3a in different cell types, an RNase protection assay (RPA) was used. A series of RPA probes spanning both the IRF-3a-specific and the common regions was designed to ensure the accurate detection of each of the IRF-3 mRNAs (Fig. 2A). Using these probes, the expression of IRF-3 and IRF-3a was assayed using RNA from normal human brain. Total RNA from HEC1B cells overexpressing IRF-3a was used as a positive control to define the pattern of protection by the three probes. Figure 2A shows that two main fragments of the expected sizes were protected by probe 1, with the upper band arising from the IRF-3a mRNA, and the lower one from the IRF-3 mRNA (lane 1). Reduction of the IRF-3a-specific region-protected probe 2 resulted in the change of migration of only the upper (IRF-3a) fragment (lane 2), whereas elimination of the unique region, and reduction in the size of the common region in probe 3, resulted in one band with faster migration (lane 3).

Figure 2.

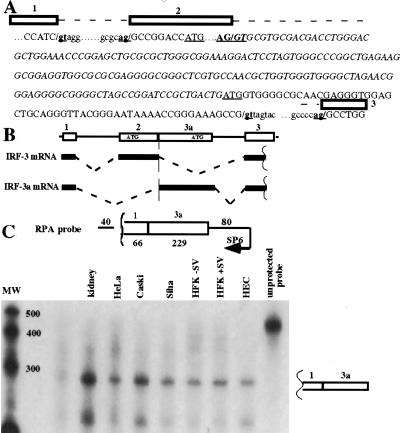

IRF-3a is generated by alternative splicing. (A) Chromosomal location of the IRF-3a-specific sequence. Open boxes correspond to exon assignments (Lowther et al. 1999). Exonic sequences are capitalized; splice donor and acceptor sites are bolded and underlined. (B) Schematic of the exon–intron structure of the 5′ part of the IRF-3 gene and of the IRF-3 and IRF-3a-specific splicing patterns. (C) RNase protection analysis of the IRF-3a-specific splicing pattern. PCR-amplified fragment of IRF-3a cDNA was used to generate an antisense riboprobe, which was hybridized with the total RNA from a panel of cell types. Lines represent vector sequences remaining in the probe. The numbers correspond to the sizes of the respective fragments. Schematic to the right of the blot shows the inferred structure of the protected fragments.

Probe 1 was further used to determine tissue distribution of the two mRNA isoforms. Figure 2B shows that both IRF-3 and IRF-3a are expressed ubiquitously, although the amounts of the transcripts vary in different tissue types and cell lines (see also Fig. 3C). More importantly, the levels of IRF-3a, in relation to that of IRF-3, vary over a greater than sevenfold range across the panel, with the highest ratio of expression found in the brain.

Figure 3.

Multiple RPA probes verify ubiquitous expression of IRF-3a and IRF-3. Different antisense riboprobes were used for RNase protection to detect the expression of IRF-3a and IRF-3 in whole human postmortem brain and in HEC1B cells overexpressing IRF-3a. (A) Schematic of the antisense probes containing regions unique to IRF-3a (white boxes), or regions in common between IRF-3 and 3a (gray boxes). Numbers indicate nucleotide length of each region. RNase protection assay using riboprobes 1, 2, and 3 described in A. Ten micrograms of total RNA from human brain or 1 μg of total RNA from HEC1B cells overexpressing IRF-3a was used for hybridization with the corresponding IRF-3a/3 probe and the β-actin probe for internal control. Numbers on the right indicate the expected sizes of the protected fragments. (B) RNase protection assay showing levels of expression of IRF-3 and IRF-3a. Total RNA from different primary cells and cell lines was subjected to RNase protection assay using probe 1 from Figure 3. The β-actin probe was used as an internal control for loading. (C) Quantitation of the mRNA ratio. RPA was subjected to PhosphorImager analysis, and total cpm of IRF-3a message was expressed as a ratio of the total cpm of the IRF-3 message.

IRF-3a is generated by alternative splicing of IRF-3 pre-mRNA

To map the chromosomal location of the IRF-3a-specific sequence, a lambda phage containing an IRF-3 genomic clone was directly sequenced using primers hybridizing to the sequences in IRF-3 exon 2 and to sequences unique to IRF-3a. The IRF-3a initiator ATG was found to lie 172 nucleotides downstream from the 3′ end of exon 2 (Fig. 3A). To determine whether IRF-3a arises from the same precursor RNA as IRF-3 by alternative splicing, PCR was performed on a HeLa cDNA library using a sense primer in the noncoding exon 1 (bases 28–48) and an antisense IRF-3a-specific primer (bases 57–34). Sequencing of the cloned 295 bp PCR fragment revealed that the IRF-3a mRNA contains the entire exon 1 juxtaposed to the sequence immediately downstream from exon 2. These data imply that the IRF-3a-specific message is produced by splicing from the 3′ end of exon 1 to the 3′ end of exon 2 (Fig. 3B).

To verify the IRF-3a-specific splicing pattern, the cloned PCR product was used to generate an antisense riboprobe for RNase protection. Figure 3C shows that a fragment of the expected size was protected in all of the cell types. The lower band protected in this assay corresponds in size to exon 3a alone, and could have arisen from protection of pre-mRNA, which is detectable in total RNA preparations with a genomic probe (data not shown). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that additional isoforms might be generated by utilization of a different 5′ splice site. Thus, the IRF-3a-specific mRNA contains noncoding exon 1, as well as the entire region between the 3′ end of exon 2 and the initiator ATG. Furthermore, these results indicate that the junction between exons 2 and 3a serves as both splice donor and acceptor, providing the first naturally occurring example of this phenomenon.

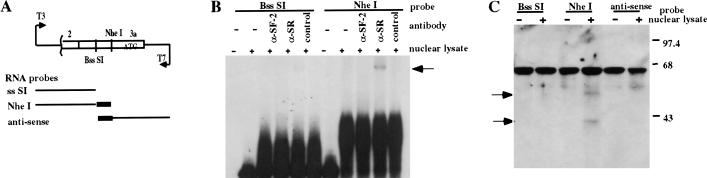

SR proteins might bias splice site selection in the IRF-3 pre-mRNA

The observation that the mRNAs for IRF-3 and IRF-3a are generated by mutually exclusive mechanisms utilizing the same sequence, raised the possibility that production of IRF-3a is regulated at the level of RNA splicing. Furthermore, the sequence at the junction of exons 2 and 3a conforms much better to a consensus for a splice donor than for a splice acceptor. A mechanism for up-regulating the use of weak alternative 3′ splice sites with splice acceptor sequences far from the consensus, involves SR splicing factors acting through enhancer sequences in the immediate downstream exons (Chabot 1996; Manley and Tacke 1996; Cooper and Mattox 1997; Blencowe 2000). To address the possibility that SR proteins might recognize sequences in the 5′ end of exon 3a, electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), using sense RNA transcripts spanning the region of interest, was carried out. Part of the genomic sequence encompassing half of exon 2 and the entire exon 3a was cloned downstream from a T3 promoter. The plasmid was linearized at various sites within the 3a exon, and radiolabeled RNA products of various lengths were synthesized by in vitro transcription (Fig. 4A). These RNA probes were then incubated either in the absence or presence of HEC1B cell nuclear lysate, and the indicated antibodies and complexes were resolved by nondenaturing acrylamide gel electrophoresis. Figure 4B shows that a distinct complex formed on the longer sense template RNA, which could be specifically supershifted using an antibody (α-SR) that recognizes all of the SR protein family members, but was not observed using the antibody to a specific SR protein, SF-2, or a control antibody. To determine which SR proteins are capable of binding this RNA sequence, an RNA pull-down assay was performed. Biotinylated RNAs were synthesized and incubated with the nuclear extracts under the conditions of the gel shift assay. RNA protein complexes were subsequently isolated using streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads, and bound proteins resolved on an SDS gel. Western analysis was then performed using the anti-SR antibody. Figure 4C shows that the longer RNA template specifically brought down two proteins identified by the α-SR antibody with mobilities of ∼40 and 55 kD, possibly corresponding to SRp40 and SRp55. Significantly, this interaction was specific for the sense message, as no SR protein binding was detected using an antisense RNA. Thus, a subset of the SR family of splicing factors, likely including SRp40 and SRp55, is capable of binding pre-mRNA arising from the IRF-3 gene within 150 nucleotides downstream from the alternative splice site.

Figure 4.

SR proteins bind to IRF-3 pre-mRNA downstream from the dual specificity splice junction. (A) RNA probes used for RNA EMSA and pull-down assays. A portion of the IRF-3 genomic clone spanning from approximately the middle of exon 2 (nucleotide 954) through the second to last codon in exon 3a (nucleotide 1301) was cloned into pBS KS vector. The plasmid was linearized either with BssSI (at nucleotide 1180) or with NheI (at nucleotide 1224) and in vitro transcribed with T3 RNA polymerase for the sense messages or with T7 RNA polymerase for the antisense message. (B) RNA EMSA showing binding of SR family member(s) to the region between the two restriction sites. The probes were incubated with HEC 1B cell nuclear lysate either in the absence or in the presence of the indicated antibodies, and complexes resolved on a polyacrylamide gel. Arrow indicates the supershift complex. (C) RNA pull-down assay to detect the interacting SR proteins. Biotinylated RNA probes were used to isolate the interacting proteins using streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads. Proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting performed using the antiSR antibody. Arrows indicate bands detected specifically with the longer sense RNA template.

To determine if the SR proteins are able to shift the balance between the two alternative processing pathways, splicing patterns of synthetic IRF-3 minigene constructs (Fig. 5A) were analyzed in HeLa cells transfected with expression plasmids for various SR protein family members. Figures 5B and 5C show that coexpression of SRp40 and SRp55 led to an increase in the ratio of IRF-3a to IRF-3-specific splicing products. This effect was dependent on the presence of the SR protein-binding site in the RNA (cf. relative ratios for construct A, open boxes, with those for construct B, hatched boxes in 5A). In addition, SRp75 strongly affected the splice site choice. However, its activity was independent of the identified SR binding domain in the IRF-3a exon and is likely to be governed by additional regulatory elements. The data presented in Figure 5 represent a single experiment. However, effects of comparable magnitude were seen in an independent repeat of this experiment.

Figure 5.

SR proteins are able to regulate splice site selection. (A) Minigene constructs used for the experiment. Two fragments of the IRF-3 genomic clones either spanning the SR protein binding site (probe A, open boxes) or not (probe B, hatched boxes) were amplified by PCR and cloned downstream from a CMV promoter for expression in mammalian cells. (B) RT–PCR analysis of spliced products. Total RNA from cells transfected with the corresponding minigene constructs and SR protein expression vectors was used for RT–PCR analysis with primers specific for the vector carrying the minigenes. (C) A subset of SR proteins shifts the balance in favor of the IRF-3a message. The data in B was quantified and plotted as the ratio of IRF-3a to IRF-3 mRNA relative to that in vector-transfected cells for each probe.

Discussion

This study describes an alternatively spliced isoform of IRF-3 and suggests that alternative splicing of IRF-3 may provide an additional level of regulation of its multifarious actions in different cellular pathways. Alternative splicing has been described for a variety of genes, particularly for those encoding transcription factors or those involved in specific aspects of development and cellular proliferation (Lopez 1995, 1998; Smith and Valcarcel 2000). Regulation of transcription factors by alternative splicing provides the potential for the generation of protein isoforms with altered DNA binding specificity, antagonistic transcription effector potential, and/or the potential to affect protein–protein interactions within large transcriptional complexes. Alternative splicing has already been described for several of the other IRF family members (Harada et al. 1994; Zhang and Pagano 1997). For regulation of IRF-3, the mechanism of splice site selection, however, appears to be unprecedented. Our analyses revealed that a single site at the end of IRF-3-specific exon 2 serves both as a splice donor in the formation of the IRF-3 message and as a splice acceptor in exclusion of exon 2 and generation of the IRF-3a message. Sequences at 5′ and 3′ splice sites usually include GU and AG at the beginning and end of the intron, as well as AG and GU at the end and beginning of the flanking exons. Thus, an AGGU sequence has the potential to serve as both 5′ and 3′ splice site. Indeed, this potential has been documented with an artificial minigene construct (Zandberg et al. 1995). However, to our knowledge such a combined splice site has not yet been observed for any natural cellular or viral gene.

Alternative splicing usually involves competition between potential splice sites. The choice of a particular site can be determined either by a strong match to the consensus sequence or by assistance of transacting factors. In particular, the SR family of splicing factors has been implicated in splice site selection. Purine-rich splicing enhancers usually lie within optional exons and facilitate splicing of the upstream intron. SR proteins appear to be involved in the function of these enhancer sequences (for reviews, see Chabot 1996; Manley and Tacke 1996; Cooper and Mattox 1997; Blencowe 2000; Smith and Valcarcel 2000). Our data indicate that a G-rich region in exon 3a, which is located between 100 and 150 nucleotides downstream from the regulated splice site, is capable of binding a subset of the SR proteins in vitro and directing splice site selection by these SR proteins in vivo. Thus, despite the fact that the site at the junction of exons 2 and 3a in the IRF-3 gene appears to have a much stronger match to the consensus for the splice donor than for the splice acceptor, SR family members have the potential to shift the balance in favor of the IRF-3a message. Given that various SR proteins, as well as their known kinase regulators, are expressed at different levels in different tissues (Zahler et al. 1993; Snow et al. 1997; Stojdl and Bell 1999), and that their activities can be cell-cycle regulated (Gui et al. 1994) and signal-induced (Screaton et al. 1995; Lynch and Weiss 2000), the levels of the IRF-3a message could vary dramatically among various cell types and under different physiologic conditions. In fact, different ratios of IRF-3a to IRF-3 messages were observed across the panel of cell lines and tissue types (Fig. 3).

It is noteworthy that the IRF-3a-specific products predominated in the in vivo splicing experiment with the minigene constructs. This demonstrates that despite a dissimilarity with the consensus sequence, the exon 2/3a junction can serve as an effective splice acceptor competing with the upstream acceptor site at the beginning of exon 2. In the context of the full-length IRF-3 pre-mRNA, the competition between the assembly of the spliceosome at the exon 1 and exon 3a pair versus the one at the exon 2 and exon 3 pair, may determine whether the unusual junction is used as a donor or acceptor in splicing. The availability of the exon 2 and exon 3 pair will depend on the relative rates of transcriptional elongation to synthesize the acceptor site at exon 3 for the junction to serve as a donor, versus assembly of the splicing machinery at the already available exon 1 and exon 3a pair. It has been shown that there can be cotranscriptional kinetic competition between alternative splicing pathways (Roberts et al. 1998). Thus, in addition to the activity of the SR proteins, factors that regulate transcriptional elongation/pausing rates, might affect the level of production of IRF-3a-specific message.

Our results suggest that the splicing of the IRF-3/IRF-3a transcripts may be regulated in a tissue-specific manner. Furthermore, our analysis of IRF-3a function led to characterization of its dominant negative effect on IRF-3-dependent IFNβ induction (AYK, LVR, and PMH, in prep.). We postulate that the relative levels of IRF-3a to IRF-3 in a given cell type may dictate the extent of IRF-3 activity in all or a subset of the IRF-3 responsive pathways. For example, virus-induced IFNβ production is likely attenuated in certain cell types due to the toxic effects of IFNβ exposure, and regulated splicing in favor of IRF-3a-specific mRNA would contribute to this attenuation.

Thus, an unprecedented alternative splicing mechanism of the IRF-3 gene-encoded transcript leads to production of two isoforms. Our results show that expression of IRF-3a is ubiquitous, but that its levels, compared to those of IRF-3, vary in a tissue-specific manner. Furthermore, our data suggest that the alternative splicing for IRF-3a expression might be further regulated by the SR proteins, as well as by conditions regulating transcriptional elongation. Because the SR proteins are known to be regulated in a cell cycle and stimuli-dependent manner, expression of IRF-3a might be further regulated under special conditions that remain to be identified.

Materials and methods

Isolation of human genomic clone of IRF-3

A lambda FIX II human genomic library (Stratagene) was screened using a 32P-labeled probe corresponding to the first 700 nucleotides of human IRF-3a. Five genomic recombinant clones containing IRF-3 were isolated after screening 6 × 105 plaques. The phage DNA from two clones was purified to homogeneity. PCR was performed using IRF-3- and 3a-specific oligonucleotides. Amplified fragments were subcloned and sequenced.

RNase protection

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (GIBCO BRL). To generate the IRF-3/3a antisense riboprobes, EcoRI–BstYI fragment from IRF-3a pcDNA3 plasmid was subcloned into the EcoRI–BamHI sites of the pBS KS vector. The latter construct was linearized with HindIII for probe 1, with PstI for probe 2, and with NdeI for probe 3. The linearized constructs were in vitro transcribed with T7 RNAP in the presence of 32P-α-UTP.

For the IFNβ antisense riboprobe, the PstI–BglII fragment of IFNβ cDNA was subcloned into pBS KS vector digested with PstI and BamHI. The resulting construct was linearized with EcoRI and in vitro transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase.

The assays were performed using RPA II or Hybspeed RPA kits from Ambion (Austin, TX).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays and RNA pull-down assay

For RNA EMSA, RNA probes were in vitro transcribed with T3 RNA polymerase in the presence of 5 μL of 32P-UTP (800 Ci/mmole, 10 mCi/mL, NEN Lifesciences) and 0.1 mM cold UTP. The full-length probes were gel purified, and 20,000 cpm were used per reaction. The gel shift reaction was performed in 10 μL using 20–30 μg of HEC 1B cell nuclear lysate in the presence of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM (CH3COO)2Mg, 100 mM CH3COOK, 2mM DTT, 0.1 mM spermine, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 5% glycerol, and 0.4 U RNasin (Promega). Added to this to reduce nonspecific binding were 0.2 μg Escherichia coli tRNA, 0.1 μg yeast total RNA, and 5 μg heparin. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, the reactions were resolved on a 4% acrylamide (40 : 1 acrylamide : bis) 5% glycerol 0.5× TBE gel at 200 V at 4°C. For supershift experiments, 1 μg of the corresponding antibodies was added to the reaction. The antiSF-2 antibody was a generous gift of Dr. Krainer (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, NY). The antiSR antibody (1H4) was from Zymed.

For RNA pull-down experiments, the above-mentioned templates were synthesized in the presence of 0.2 mM biotin-16-UTP (Roche Biochemicals) and 0.3 mM cold UTP. The probes were gel-purified, and 100 pg of RNA were incubated with 20–30 μg of HEC 1B cell nuclear lysate under the gel-shift conditions. After incubation, 10 μL of M-280 streptavidin magnetic beads (Dynal), pre-equilibrated in the binding buffer, were added to the reaction. The samples were then incubated on ice for 15 min with intermittent gentle vortexing, and RNA–protein complexes were isolated using a magnetic stand (Dynal). After two washes with the binding buffer, the beads were resuspended in a 1x SDS buffer, and bound proteins were resolved on a 10% SDS gel and detected by Western analysis using α-SR 1H4 antibody.

In vivo splicing reactions

Synthetic minigene constructs were generated from the genomic IRF-3 clone by PCR using the primers hybridizing in exons 1 and 3a. The sequences of the primers were as follows: exon1, CTCGAGTTT GAGAGCTAC; exon 3a probe A, GTAACCCTGCAGCTCCAC; exon 3a probe B, CAGCTCCGGGTTTCCAG. PCR products were initially cloned into the PCR-Blunt II vector (Invitrogen), and then recloned into pcDNA3 using NotI–KpnI digest. The pcDNA3 constructs were cotransfected with various SR protein expression vectors into HeLa cells using Lipofectamine2000 reagent (GIBCO BRL). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cDNA corresponding to the spliced products was synthesized from 3 μg of total RNA using AMV-RT (GIBCO BRL), and 40% of the product used for a 25 cycle PCR using Pfx polymerase (GIBCO BRL). The primers used in RT and PCR steps were derived from the sequences of the pcDNA3 vector.

Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Ro for expert technical assistance. We are grateful to Dr. Adrian Krainer for antiSF-2 antibody, to Dr. Robert Lafyatis for the SR protein expression vectors, and to Jeffrey Sklar for the human genomic library. Our appreciation to Dr. Paula Pitha for sharing reagents. We thank Dr. Juan Valcarcel for helpful discussion. L.V.R. was supported by fellowship grants 5 F32 AI09167-02 from the NIAID and from Aid for Cancer Research. A.Y.K. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Predoctoral Fellow. This research was supported by NIH grant PO1 AI 42257 to P.M.H.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL peter_howley@hms.harvard.edu; FAX (617) 432-2882.

Article and publication are at www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.813800.

References

- Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. NF-κB: Ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe BJ. Exonic splicing enhancers: Mechanism of action, diversity and role in human genetic diseases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:106–110. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot B. Directing alternative splicing: Cast and scenarios. Trends Genet. 1996;12:472–478. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TA, Mattox W. The regulation of splice-site selection, and its role in human disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:259–266. doi: 10.1086/514856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui JF, Lane WS, Fu XD. A serine kinase regulates intracellular localization of splicing factors in the cell cycle. Nature. 1994;369:678–682. doi: 10.1038/369678a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Kondo T, Ogawa S, Tamura T, Kitagawa M, Tanaka N, Lamphier MS, Hirai H, Taniguchi T. Accelerated exon skipping of IRF-1 mRNA in human myelodysplasia/leukemia: A possible mechanism of tumor suppressor inactivation. Oncogene. 1994;9:3313–3320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N. The role of interferon regulatory factors in the interferon system and cell growth control. Biochimie. 1998;80:641–650. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heylbroeck C, Balachandran S, Servant MJ, DeLuca C, Barber GN, Lin R, Hiscott J. The IRF-3 transcription factor mediates Sendai virus-induced apoptosis. J Virol. 1999;74:3781–3792. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3781-3792.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Kim TY, Song YH, Min IM, Yim J, Kim TK. Activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 in response to DNA-damaging agents. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30686–30689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Heylbroeck C, Pitha PM, Hiscott J. Virus-dependent phosphorylation of the IRF-3 transcription factor regulates nuclear translocation, transactivation potential, and proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2986–2996. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Heylbroeck C, Genin P, Pitha PM, Hiscott J. Essential role of interferon regulatory factor 3 in direct activation of RANTES chemokine transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:959–966. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AJ. Developmental role of transcription factor isoforms generated by alternative splicing. Dev Biol. 1995;172:396–411. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.8050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Alternative splicing of pre-mRNA: Developmental consequences and mechanisms of regulation. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:279–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowther WJ, Moore PA, Carter KC, Pitha PM. Cloning and functional analysis of the human IRF-3 promoter. DNA Cell Biol. 1999;18:685–692. doi: 10.1089/104454999314962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch KW, Weiss A. A model system for activation-induced alternative splicing of CD45 pre-mRNA in T cells implicates protein kinase C and Ras. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:70–80. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.70-80.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamane Y, Heylbroeck C, Genin P, Algarte M, Servant MJ, LePage C, DeLuca C, Kwon H, Lin R, Hiscott J. Interferon regulatory factors: The next generation. Gene. 1999;237:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley JL, Tacke R. SR proteins and splicing control. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1569–1579. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Mowen K, Rodems S, Weaver B, Reich N, Spector D, David M. Cytomegalovirus activates interferon immediate-early response gene expression and an interferon regulatory factor 3-containing interferon-stimulated response element-binding complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3796–3802. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H, Hiscott J, Pitha PM. The growing family of interferon regulatory factors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8:293–312. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GC, Gooding C, Mak HY, Proudfoot NJ, Smith CWJ. Co-transcriptional commitment to alternative splice site selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5568–5572. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.24.5568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronco LV, Karpova AY, Vidal M, Howley PM. Human papillomavirus 16 E6 oncoprotein binds to interferon regulatory factor-3 and inhibits its transcriptional activity. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:2061–2072. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Screaton GR, Caceres JF, Mayeda A, Bell MV, Plebanski M, Jackson DG, Bell JI, Krainer AR. Identification and characterization of three members of the human SR family of pre-mRNA splicing factors. EMBO J. 1995;14:4336–4349. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CWJ, Valcarcel J. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing: The logic of combinatorial control. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:381–388. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow BE, Heng HH, Shi XM, Zhou Y, Du K, Taub R, Tsui LC, McInnes RR. Expression analysis and chromosomal assignment of the human SFRS5/SRp40 gene. Genomics. 1997;43:165–170. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojdl DF, Bell JC. SR protein kinases: The splice of life. Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;77:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wathelet M, Lin CH, Parekh B, Ronco LV, Howley PM, Maniatis T. Virus infection induces the assembly of coordinately activated transcription factors on the IFN-β enhancer in vivo. Mol Cell. 1998;1:507–518. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver BK, Prasanna Kumar K, Reich NC. Interferon regulatory factor 3 and CREB-binding protein/p300 are subunits of double-stranded RNA-activated transcription factor DRAF1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1359–1386. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M, Suhara W, Fukuhara Y, Fukuda M, Nishida E, Fujita T. Direct triggering of the type I interferon system by virus infection: Activation of a transcription factor complex containing IRF-3 and CBP/p300. EMBO J. 1998;17:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahler AM, Neugebauer KM, Lane WS, Roth MB. Distinct functions of SR proteins in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Science. 1993;260:219–222. doi: 10.1126/science.8385799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandberg H, Moen TC, Baas PD. Cooperation of 5′ and 3′ processing sites as well as intron and exon sequences in calcitonin exon recognition. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:248–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Pagano JS. IRF-7, a new interferon regulatory factor associated with Epstein-Barr virus latency. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5748–5757. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]