Most health professionals recognize that patients and other consumers of health care information are not familiar with medical terminology. When MEDLINE searching was restricted to the few who understood Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), medical terminology, and the intricacies of searching the database, there was little need to accommodate the uninitiated. Health professionals knew that over the years MEDLINE has adopted a number of mappings from entry terms to the MeSH headings. Many of these mappings are from the extensive entry vocabulary of MeSH, described on the home page as “over 300,000 terms.”* Because of this large entry vocabulary, a search for “heart attack” now maps to “myocardial infarction,” a term consumers are unlikely to use.

With knowledge about such mappings, health professionals might expect all lexical variants of a term to be mapped to a single form. The early tests of information retrieval systems noted the problem of lexical variants, and one of the purposes of controlled vocabularies was to control for such grammatical variations [1]. In fact, the management of such variants is still a topic of research [2].

The data presented here showed that the expectation that all variants would be mapped to the MeSH term was not true. The researchers used the topic “bloody nose” (scientific name, “epistaxis”) and two lexical variants to search a commercially available and a free system offering access to MEDLINE (OVID and PubMed) and on a sample of Websites consumers might access (MEDLINEplus, NetWellness, drkoop.com, Excite Health, and CBSHealthWatch). We also tested two other phrases for which we recognized lexical variants (“pink eye” or “pinkeye” and “color blindness” or “color blind” and their British equivalents) on MEDLINE to determine if our initial query was idiosyncratic.

The National Library of Medicine offers free access to MEDLINE from its home page through either Internet Grateful Med (IGM) or PubMed. Although the interfaces of the two systems differ considerably, both perform the same search. The details of the search when we entered “bloody nose” were:

bloody (all fields) and nose (all fields)

The resulting set had twenty items. One title contained the phrase “bloody nose” (“The Role of Branhamella Catarrhalis in the ‘Bloody-Nose Syndrome’ of Cynomolgus Macaques”). Consumers would find little of value in the other items in this set. Some of the other irrelevant titles were:

“Exhaled Nitric Oxide in Patients with Wegener's Granulomatosis”

“Compensatory Response of Colon Tissue to Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis”

“The Oral and Intratracheal Toxicities of ROUNDUP and Its Components to Rats”

Because these systems offered the option of clicking on Related Articles, our imagined consumers could retrieve some relevant items from the system by clicking on the title of an item with bloody nose in it. Browsing the related items revealed that the condition Branhamella was the focus of the new search, not the concept of bloody nose. Thus, the search term “bloody nose” retrieved no relevant documents.

OVID also provides access to MEDLINE. The OVID search screen has a box that allows users to choose the Map to Subject Heading option. When this box is clicked, the system automatically attempts to map the search term to the most appropriate MeSH term. When we clicked the box and entered the term “bloody nose,” the following list of terms was displayed:

Glycine;

Herbicides;

Surface-Active Agents;

Polyethylene Glycols;

Administration, Oral;

Lung;

Dose-Response Relationship, Drug;

Rats, Wistar;

“bloody nose”.mp. (Search as Keyword)

Most consumers would not see an obvious relationship between any of the terms listed and the topic, so they would likely choose the final option, “bloody nose.mp.” The result of this search was a single citation, which was about the effects of herbicides (the one with ROUNDUP above).

This set of results is not of particular interest, because it illustrates that MEDLINE is not designed for consumers, as stated in the first paragraph. What is interesting about this example is that by using a grammatical variation of the original term, consumers would get a completely different set of results. Bloody nose is a phrase composed of an adjective and a noun. Reversing the order of the words and moving from the adjectival to the noun form results in the noun-noun phrase “nose bleed.” The results of a search with “nose bleed” are different. This phrase, too, has a variant, the single word “nosebleed.”

When we entered “nose bleed” as a search term on either PubMed or IGM, the resulting set contained 1,849 items. When we clicked on the Details box, the search clearly was for:

epistaxis (MeSH) or nose bleed.tw

When we entered the composite noun “nosebleed,” the same set is retrieved and clicking on the details box reveals that the search was performed as follows:

epistaxis (MeSH) or nosebleed.tw

Using either of these options, we got a large set containing titles such as the following:

“59-Year-Old Man with Epistaxis, Headache, and Cough”

“Successful Epistaxis Control in a Patient with Glanzmann Thrombasthenia by Increased Bolus Injection Dose of Recombinant Factor VIIa”

“A New Bipolar Diathermy Probe for the Outpatient Management of Adult Acute Epistaxis”

“The Use of Nasal Endoscopy to Control Profuse Epistaxis from a Fracture of the Basi-Sphenoid in a Seven-Year-Old Child”

If we clicked on the Details button and saw epistaxis, we might have found articles in the resulting set of interest. If we did not, we would not have found a relevant title among the first thirty items on the list.

With OVID, if the Map to Subject Heading box was clicked, then either nose bleed or nosebleed would map to epistaxis, and we saw a message to that effect. If we chose just the MeSH term, the resulting set had 1,833 items with titles like the following:

“Recurrent Epistaxis in a College Athlete”

“Comparison of Computer-assisted Instruction and Seminar Instruction to Acquire Psychomotor and Cognitive Knowledge of Epistaxis Management”

“A Randomized Clinical Trial of Antiseptic Nasal Carrier Cream and Silver Nitrate Cautery in the Treatment of Recurrent Anterior Epistaxis”

“A Treatment Algorithm for the Management of Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia”

Because this system shows the mapping to the user, the resulting set may seem more relevant with the knowledge that epistaxis means bloody nose.

While PubMed does not show any mappings directly to the user in its search process, it does offer access to the MeSH browser where the user could see some relationships between terms. Because consumers might try to use the MeSH browser, we tested all our variations in it. The results showed the same disparities as the MEDLINE retrieval. When we entered “bloody nose,” the response was “No term found.” Both nose bleed and nosebleed led directly to the MeSH Descriptor Data, where both appeared as entry terms for the scientific name, epistaxis.

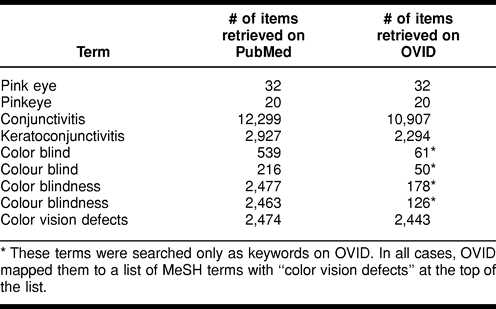

We have focused our discussion so far on a single term and its variations but found similar results, at least on MEDLINE, with two other phrases. Pink eye could be written as two words or one, pinkeye. We could talk of being color blind or having color blindness or use their equivalent British spellings. In both cases, searching for the variations of the terms resulted in different retrieval, and consumers are not always directed to the official MeSH term. Table 1 contains the results for searching MEDLINE both through PubMed and through OVID. We would likely get similar different results with a search of Websites, but we did not test that hypothesis.

Table 1 Results of searching MEDLINE for information on pink eye and color blindness

If the OVID Map to Subject Heading box was clicked, pink eye mapped to a list with keratoconjunctivitis first and with “conjunctivitis” tenth. Pinkeye mapped to a different list with keratoconjunctiitis second and conjunctivitis fifth. Again, we tested the MeSH browser to see if variations all led to the MeSH term. Pink eye resulted in a list of three terms:

pink-eyed dilution protein

pink-eyed dilution gene product

pink-eyed dilution protein, human

None of these terms are related to conjunctivitis or any eye disease. When we entered the single word “pinkeye,” the response was “No term found.”

If the OVID Map to Subject Heading box was clicked, all forms and spellings of color blind(ness) mapped to a list with the MeSH term “color vision defects” first. The MeSH browser had varying results depending on which lexical variant was used as the search term for the browser. Color blind resulted in a list of eight terms, beginning with the MeSH term color vision defects. The second term was “color blindness,” and the remaining six all had qualifiers. Clicking on either color vision defects or color blindness resulted in the MeSH Descriptor Data display where both color blind and color blindness were displayed as entry terms. Either of the British spellings resulted in “No term found.”

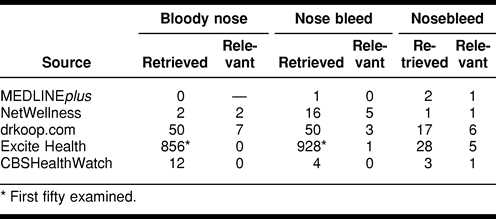

This tangled verbal variation for a single concept was not restricted to MEDLINE alone. We searched five health sites on the Web and found variations in retrieval on each site for the concept of bloody nose, our original inquiry. These were obviously not the only such sites but were merely examples. One of these sites (drkoop.com) was chosen because of its popularity as reported in the media, one (MEDLINEplus) because it was the official source of consumer health information coming from the National Library of Medicine, and one (NetWellness) because it was developed by librarians. The other two were the result of clicking on the Search button on a browser and then clicking on health information.

The results of using the three variants of bloody nose, nose bleed, or nosebleed are shown in Table 2. Obviously, what consumers will find depends on which grammatical variation of the concept is the search term. All three members of our research team evaluated the results for relevance and used the single criterion that the source appeared to be about bloody noses. We only evaluated the items (articles, consumer emails, or specially designed items) that were available on the site we were searching. In other words, we did not try to evaluate related Websites, even though some of the sites retrieved them. We used only the concept of bloody nose for this sample of Web searches, but we surmised that a similar pattern would emerge if we used the variations for color blindness or pink eye.

Table 2 Results of searching Internet sources with bloody nose and its lexical variants

The point of these examples is to highlight the problems that can be encountered by using the “wrong” grammatical variation. Both PubMed and the OVID access to MEDLINE will map the user to the MeSH term, but only if the appropriate term is entered initially. Nose bleed and nosebleed are both mapped to epistaxis in MeSH, but bloody nose is not. With the OVID system, pink eye and all spellings and grammatical variations of color blindness map to appropriate MeSH headings, although consumers may need to know that conjunctivitis is a medical term for pink eye. With the PubMed system, however, the results differ considerably depending on the lexical variant entered.

If consumers are to use sources such as MEDLINE successfully, it becomes important that their language accesses pertinent literature. Even the Metathesaurus of the Unified Medical Language System [3, 4], rich as it is, does not contain color blind, colour blind, or bloody nose. It does include both variants for pink eye and the British and American spellings for color blindness.

If our health care system is to be driven by the informed decisions of patients and health care consumers [5], it is important that they are able to successfully use sources of health care information such as MEDLINE. Accordingly, it is important that the language of patients and consumers accesses pertinent literature. Yet our research, though preliminary, suggests that this is far from the case. From a terminological point of view, improving health care information retrieval for consumers requires that more consumer terms, with all of their lexical variations, be mapped to their MeSH counterparts. Gathering all consumer terms may be an impossible goal, but studying ways to add additional lexical variants, at the very least British equivalent spellings, could significantly improve retrieval for consumers.

Footnotes

* The MeSH home page may be viewed at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/meshhome.html.

REFERENCES

- Lancaster FW. Vocabulary control for information retrieval. 2d ed. Arlington, VA: Information Resources Press, . 1986 [Google Scholar]

- Divita G, Browne AC, and Rindflesch TC. Evaluating lexical variant generation to improve information retrieval. In: Chute C, ed. AMIA '98 annual symposium: a conference of the American Medical Informatics Association, November 7–11, 1998. Orlando, FL: The Association, . 1998: 775–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys BL, McCray AT, and Cheh ML. Evaluating the coverage of controlled health data terminologies: report on the results of the NLM/AHCPR large scale vocabulary test. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997 (Nov–Dec); 4(0):484–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys BL, Lindberg DA, Schoolman HM, and Barnett GO. The Unified Medical Language System: an informatics research collaboration. J Am Med Inform Assoc . 1998 (Jan–Feb); 0:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy CM. Consumer preferences: path to improvement? Health Serv Res. 1999 Oct; 34(0):804–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]