Abstract

Objective

We examined changes in drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and dietary restraint across the menstrual cycle and associations between these symptoms and ovarian hormones in two independent samples of women (N = 10 and 8 women, respectively) drawn from the community.

Method

Daily self-report measures of disordered eating and negative affect were completed for 35–65 days. Daily saliva samples were assayed for estradiol and progesterone in Study 2 only.

Results

Levels of body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness were highest during the mid-luteal/pre-menstrual phases in both studies and were negatively associated with estradiol, and positively associated with progesterone. By contrast, dietary restraint showed less variation across the menstrual cycle and weaker associations with ovarian hormones.

Discussion

Differential associations between ovarian hormones and specific disordered eating symptoms point to distinct etiological processes within the broader construct of disordered eating.

Keywords: estradiol, progesterone, ovarian hormones, menstrual cycle, eating disorders, disordered eating, drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint

Eating disorders are one of the most sex differentiated forms of psychopathology with the female-to-male ratio ranging from 4:1 to 10:1 (1). Research indicates that ovarian hormones may be important biological factors contributing to the etiology and increased risk for eating disorders in women (2–4). Ovarian hormones regulate food intake in a variety of animal species. For example, removal of the source of ovarian hormones through bilateral ovariectomy increases food intake in animals, and the administration of estradiol reverses this effect (5–7). In contrast, progesterone has stimulatory effects on food intake (5, 6), in part, by antagonizing the effects of estradiol (8). These findings highlight the central role of ovarian hormones in the control of food intake.

In addition to influencing food intake in general, ovarian hormones also have been implicated in the etiology and expression of eating disorder symptoms (2, 3, 9). Recent studies have used within-subject, longitudinal designs across the menstrual cycle to examine the role of ovarian hormones in binge eating behaviors, in particular (2, 3). The menstrual cycle provides a strong quasi-experimental design for examining hormone-behavior associations, as all normally cycling women experience natural changes in levels of estradiol and progesterone to prepare for conception (2, 3). Further, changes in ovarian hormones that precede changes in binge eating most likely represent the influence of hormones on binge eating rather than the reverse (2, 3).

Data thus far suggest that binge eating fluctuates across the menstrual cycle, with levels of binge eating being highest in the mid-luteal and pre-menstrual phases compared to other cycle phases (2, 3, 10). Moreover, estradiol is inversely associated, and progesterone is positively associated, with increased binge eating across the menstrual cycle (2, 3). Hormone-binge eating associations are independent of body weight and menstrual cycle changes in negative affect (2, 3), suggesting a direct effect of ovarian hormones on binge eating.

To date, studies examining phenotypic associations between hormones and disordered eating have focused almost exclusively on binge eating. This emphasis makes sense given extant data implicating ovarian hormones in the control of food intake (see above). However, it is important to examine the influence of hormones on other types of disordered eating symptoms such as drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and dietary restraint. These symptoms are present in nearly all eating disorders (i.e., anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, eating disorders not otherwise specified) and are robust, prospective risk factors for the development of clinically significant eating disorders (11). The fact that these symptoms are also correlated with binge eating suggests that they may exhibit associations with ovarian hormones, either directly or indirectly through binge eating. Examining the extent to which hormone-disordered eating associations are specific to binge eating or are present for a range of symptoms will increase our understanding of the role of ovarian hormones in the spectrum of eating pathology.

To our knowledge, the only other disordered eating symptom to be examined across the menstrual cycle is body dissatisfaction. Body dissatisfaction was found to be highest in the peri-menstrual phase (pre-menstrual plus menstrual phases) compared to the follicular/mid-luteal phases (12–14). These patterns partially conform to results for binge eating, as binge eating also was elevated pre-menstrually in several studies (2, 3, 10). However, studies of body dissatisfaction have only assessed participants on one occasion during each cycle phase (12–14), whereas studies of binge eating consisted of daily symptom reports across the menstrual cycle (2, 3, 10). Thus, menstrual cycle changes in body dissatisfaction must be examined via longitudinal studies that employ more frequent observations. In addition, previous research has not examined whether changes in ovarian hormones, mood, or physical symptoms account for menstrual cycle changes in body dissatisfaction. Similar to binge eating, low levels of estradiol during the pre-menstrual phase may lead to higher levels of body dissatisfaction (2, 3). Alternatively, body dissatisfaction may be elevated during the peri-menstrual period as a result of psychological factors (e.g., increased negative affect), increases in food intake (including binge eating; 2, 3), or common physical changes (e.g., bloating) that occur during these phases (13). Although additional research is needed, preliminary findings highlight the possible presence of hormone-behavior associations for other disordered eating symptoms and a need to directly examine their presence.

Notably, one previous study reported significant positive associations between estradiol levels and a composite measure of disordered eating symptoms assessing drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, binge eating, and compensatory behaviors (15). However, this study used onetime assessments of estradiol during the follicular phase only, and post-hoc analyses indicated that the data collection method (i.e., salivettes) likely reversed the direction of associations (from negative to positive) between estradiol and disordered eating (16).

Given the above, additional studies are needed to investigate associations between ovarian hormones and disordered eating symptoms using within-person, longitudinal designs that can clarify the nature and direction of associations. We conducted two pilot studies to address this gap. In Study 1, we compared fluctuations in drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and dietary restraint across menstrual cycle phases in a community sample of women. In Study 2, we extended these findings by directly investigating associations between ovarian hormones and these disordered eating symptoms across the menstrual cycle in an independent, community sample of women. Both studies also included negative affect and emotional eating as two potential “third variables” in analyses in order to determine if changes in disordered eating symptoms occurred above and beyond menstrual cycle changes in these other potentially important variables.

STUDY 1

METHODS

Participants

Participants included 10 adult women who were recruited through public advertisements at the University of Iowa and surrounding community. Inclusion criteria are detailed elsewhere (2), and thus are only briefly mentioned here. These criteria included a body mass index between 19–29 kg/m2, regular menstrual cycles, no pregnancy or lactation in the past 6 months, no hormonal, psychotropic, or steroid medication use in the past 8 weeks, and no history of diseases or medical conditions that could impact hormone functioning. Participants had a mean age of 28.0 years (SD = 8.1) and a mean BMI of 22.9 kg/m2 (SD = 4.2). Eight participants were Caucasian and 2 were Asian. All but one participant was in college or had completed a college degree.

Procedures

Procedures were identical to those reported in Klump et al. (2). Briefly, participants completed behavioral questionnaires each evening for 35 consecutive days in order to capture one full menstrual cycle. Evening assessments were chosen because they have been found to maximize convenience and reduce potential recall biases, as compared to recalling the previous day’s behaviors each morning (3, 10). Participants came into the laboratory for two study visits. During the intake assessment, participants provided informed consent, data collection procedures were described, and study materials were distributed. At the end of the 35-day period, participants returned study materials and were compensated $75 for their participation.

Measures

Disordered eating attitudes

Subscales from the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI; 17) were used to assess daily changes in levels of drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction. The Drive for Thinness subscale consists of 7 items that inquire about preoccupation with weight, dieting, and the pursuit of thinness. The Body Dissatisfaction subscale is composed of 9 items that ask about dissatisfaction with the size and shape of certain parts of one’s body. The instructions for both scales were modified with permission to inquire about disordered eating attitudes on that day.

The Drive for Thinness and Body Dissatisfaction subscales exhibited high internal consistency (α’s = .85–.92; 17, 18) and test-retest reliability (r’s = .70–.74 over 1 year; 19) in previous work. Convergent and discriminant validity is also well-established, as these measures correlate with overall measures of disordered eating (i.e., Eating Attitudes Test total score; 18) and discriminate between patients with eating disorders and healthy control women (17). In Study 1, internal consistencies for the modified EDI Drive for Thinness and Body Dissatisfaction subscales were .92 and .97, respectively.

Dietary Restraint

Dietary restraint was assessed using the Cognitive Restraint scale from the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ; 20). The TFEQ Restraint scale consists of 21 items that inquire about both conscious efforts to restrict food intake and dietary behaviors that lead to weight loss/maintenance. As with the EDI scales, the instructions for this measure were modified with permission to inquire about restrained eating over the current day.

Internal consistency of the unmodified Restraint scale is excellent (α = .93; 20), and test-retest reliability over 1 year is also very high (r = .81; 21). In addition, this scale correlates highly with other measures of dietary restraint (e.g., Dutch Restrained Eating Scale; r = .66; 22). Internal consistency of the modified version of the TFEQ Restraint scale in Study 1 was high (α =.87).

Emotional Eating

Binge eating was assessed using the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) Emotional Eating scale (23), as this measure demonstrated the most robust hormone-behavior relationships across the menstrual cycle in previous research (2). The Emotional Eating scale is composed of 13 items and assesses the tendency to eat large amounts of food for reasons that are typically endorsed by individuals who binge eat. The instructions for this scale were modified with permission to ask about binge eating over the current day.

The DEBQ Emotional Eating scale has been shown to fluctuate across the menstrual cycle (2) and is able to distinguish between individuals who have bulimia nervosa/binge eating, overweight individuals, and normal-weight individuals (24). Previous studies report high internal consistency (α = .93) and good factor validity of the DEBQ Emotional Eating scale (23). The internal consistency of the modified version was also excellent (α = .93) in Study 1.

Mood symptoms

Daily fluctuations in negative affect were measured using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; 25). The PANAS was designed to assess changes in mood states (e.g., depression, anxiety) over differing time periods, including a single day, and thus no modifications to the PANAS were required. Good convergent and discriminant validity have been demonstrated for the PANAS (25), and internal consistency of the Negative Affect scale was .85 in Study 1.

Menstrual period

In order to determine menstrual cycle phase, participants reported dates of menstrual bleeding in a daily log book.

Data Analyses

Data analytic procedures followed those of Lester et al. (10). Briefly, for each subject, the first day of menstrual bleeding was labeled day +1 and the previous day was labeled day -1. Five day rolling averages were calculated for each measure (i.e., drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint, negative affect, emotional eating) by participant. For example, the level of dietary restraint on day −5 was computed as the average level of symptoms on days −7 to −3 inclusive. A minimum of 3 data points were needed to calculate a rolling average value for each variable on each of the 35 days. Across all participants, only 3.5% of data were missing across the 35-day collection period. However, these rates of missing data only resulted in missing rolling average values on 9 occasions across all participants.

Daily averages were converted to Z scores based on each participant’s overall mean and standard deviation for each measure across data collection. In order to determine whether menstrual cycle fluctuations in disordered eating symptoms persist after controlling for negative affect and emotional eating, the daily rolling average of these “third” variables was partialled out of the daily rolling average for the disordered eating symptom score. This was done by conducting regressions in which negative affect and emotional eating were entered as independent variables and the disordered eating symptom was entered as the dependent variable. Standardized residual scores were saved and used in the partial analyses, as these values represent the daily level of each disordered eating symptom after accounting for the effects of negative affect and emotional eating.

Menstrual cycle phases were defined as follows. The ovulatory phase included days −15 to −12 (i.e., 12–15 days before the first day of menstrual bleeding), the mid-luteal phase included days −9 to −5, the pre-menstrual phase included days −3 to +1, and the follicular phase included days +5 to +10. Daily symptom scores were averaged across the days of each cycle phase for each participant. Contrast analyses were used to examine the hypothesis that levels of disordered eating symptoms would be higher in the mid-luteal/pre-menstrual phases compared to the follicular/ovulatory phases.

RESULTS

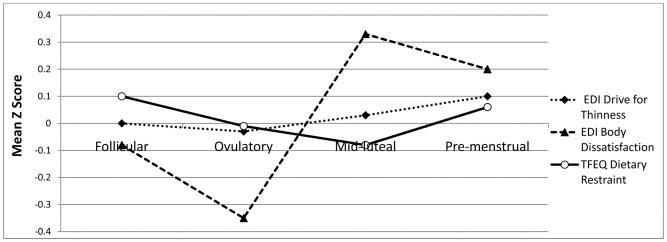

Of the three disordered eating symptoms, body dissatisfaction displayed the most robust pattern of fluctuation across the menstrual cycle (see Figure 1). Contrast analyses indicated that levels of body dissatisfaction were significantly higher in the mid-luteal/pre-menstrual phases compared to the follicular/ovulatory phases (see Table 1). Results did not change substantially after controlling for negative affect and emotional eating.

Figure 1. Levels of Drive for Thinness, Body Dissatisfaction, and Dietary Restraint across Menstrual Cycle Phases in Study 1.

Mean Z scores represent 5-day rolling averages calculated within subjects and then averaged across subjects. Follicular phase includes days +5 to +10; Ovulatory phase includes days −15 to −12; Mid-luteal phase includes days −9 to −5; Pre-menstrual phase includes days −3 to +1; EDI = Eating Disorder Inventory; TFEQ = Three Factor Eating Questionnaire.

Table 1.

Mean Z score by cycle phase and contrast analyses comparing values in the follicular/ovulatory phase to those in the mid-luteal/pre-menstrual phase in Study 1.

| Variable | Follicular | Ovulatory | Mid-luteal | Pre-menstrual | t(36) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDI Drive for Thinness | ||||||

| Initial Analyses | 0 | −.03 | .03 | .10 | .50 | .62 |

| Controlling for | .05 | −.05 | −.01 | .01 | .004 | .99 |

| NA and EE | ||||||

| EDI Body Dissatisfaction | ||||||

| Initial Analyses | −.08 | −.35 | .33 | .20 | 2.65 | .01 |

| Controlling for | −.02 | −.33 | .28 | .09 | 2.21 | .03 |

| NA and EE | ||||||

| TFEQ Dietary Restraint | ||||||

| Initial Analyses | .10 | −.01 | −.08 | .06 | −.28 | .79 |

| Controlling for | .10 | −.07 | −.13 | .10 | −.09 | .93 |

| NA and EE | ||||||

Note. EDI = Eating Disorder Inventory; TFEQ = Three Factor Eating Questionnaire; NA = negative affect; EE = emotional eating.

Drive for thinness appeared to exhibit a similar pattern of menstrual cycle changes (i.e., increases during the mid-luteal and premenstrual phases), but the changes were less dramatic than that observed for body dissatisfaction (see Figure 1). Indeed, contrast analyses indicated no significant phase differences, particularly after controlling for negative affect and emotional eating (see Table 1).

Finally, levels of dietary restraint also varied less across the menstrual cycle, and the pattern of fluctuation was opposite to that of body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness (i.e., increases during the follicular phase; see Figure 1). However, contrast results across phase were non-significant both before and after controlling for negative affect and emotional eating.

DISCUSSION

Findings from Study 1 suggest that levels of body dissatisfaction significantly fluctuate across the menstrual cycle, and this is not primarily a function of changes in negative affect or emotional eating. This is similar to the pattern of findings for binge eating in both clinical and non-clinical samples (2, 3, 10), and indicates that body dissatisfaction may be associated with changes in ovarian hormones across the menstrual cycle. Levels of drive for thinness and dietary restraint varied less across the menstrual cycle and were not significantly different across the mid-luteal/pre-menstrual and follicular/ovulatory phases.

Notably, this study defined menstrual cycle phase based on participant self-report of dates of menstrual bleeding. Although self reports provide a reasonably accurate gauge for retrospectively assessing the mid-luteal phase, they provide a weak indicator of the duration of the follicular phase or timing of ovulation. Furthermore, this method does not account for women experiencing anovulatory cycles. In such cases, the mid-luteal phase is reduced in length and is not associated with increased food intake (26). Directly assaying ovarian hormone concentrations provides a much more precise indicator of the presence of ovulation and allows for direct examination of estradiol’s and progesterone’s ability to predict disordered eating symptoms. Study 2 addressed these issues by assessing ovarian hormone concentrations and examining their associations with disordered eating across the menstrual cycle.

STUDY 2

METHODS

Participants

Participants for this study included 8 healthy adult female twins (3 monozygotic twin pairs, 1 dizygotic twin pair) from the Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR: 27). The MSUTR is a population-based twin registry focused on understanding biological and environmental risk factors for internalizing and externalizing disorders across development. Inclusion/exclusion criteria for the twins included in Study 2 were identical to those for Study 1 (see above). All twins were full-time college students with a mean age of 20.3 years (SD = 2.37) and a mean BMI of 21.9 kg/m2 (SD = 3.18). Six participants were Caucasian and 2 were African-American.

Procedures

Study procedures were identical to those reported in Klump et al. (2). Briefly, participants completed behavioral questionnaires and saliva sample collection for 65 consecutive days (i.e., two menstrual cycles). Saliva samples were collected each morning by having participants passively drool into a cryovial tube through a straw within 30 minutes of awakening. We used this passive drooling method for saliva collection instead of salivettes to ensure that results were not unduly influenced by data collection methods. Behavioral questionnaires were completed each evening after 5 pm. The timing of saliva and behavioral data collection was such that ovarian hormone measurements clearly preceded the report of disordered eating symptoms each day.

In addition, participants came into the laboratory for three study visits. During the intake assessment, participants gave their informed consent, study procedures were described, and study materials were distributed. Approximately 30 days later, participants returned for their intermediate assessment, and research assistants collected study materials and assessed continued study eligibility and compliance. At the end of the data collection period, participants returned their study materials and were compensated $175 for their participation.

Measures

Measures assessing disordered eating symptoms and negative affect were identical to those used in Study 1. Internal consistencies for these measures in Study 2 were excellent: Drive for Thinness (α = .89), Body Dissatisfaction (α = .95), Dietary Restraint (α = .84), Emotional Eating, (α = .98), Negative Affect (α = .91).

Menstrual Period

Participants reported dates of menstrual bleeding in a daily log book.

Ovarian Hormones

Daily saliva samples were assayed for both estradiol and progesterone levels. Using saliva to examine hormone concentrations has distinct advantages over other biological fluids (e.g., serum; 28). Saliva sampling is less invasive, especially when repeated samples are needed, and salivary hormone levels reflect unbound hormones that provide a more accurate estimate of active estradiol and progesterone. Finally, previous research has reported that saliva sampling is associated with greater compliance and more robust hormone-behavior associations that blood spot sampling (3).

Saliva samples for each participant were stored until all of her saliva tubes were received; assay runs were then conducted on all 65 tubes for each participant. Estradiol assays were conducted by Salimetrics, LLC (State College, PA, USA) using radioimmunoassay techniques (Diagnostic Systems Laboratory, Webster, TX, USA). Progesterone assays were conducted by the Michigan State University Genetics Service Laboratory, also using radioimmunoassay (Diagnostic Systems Laboratory). All assay procedures used previously described methods (29). Average intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) for estradiol were less than 6% and 9%, respectively, and the lower limit of sensitivity was 0.25 pg/ml. For progesterone, CV values for progesterone were 12% and 14%, and assay sensitivity was 10 pg/ml.

Data analyses

Data analytic procedures followed those of Edler et al. (3) and Klump et al. (2). Similar to Study 1, the first day of menstrual bleeding for each participant was labeled day +1 and the previous day was labeled day −1. The menstrual cycles of each subject were then aligned based on this numbering scheme. Inspection of each subject’s hormone profile confirmed the presence of ovulation in all participants by examining a peak in estradiol between days −18 to −12 and a peak in progesterone between days −9 to −5. Daily assessments of hormone levels allowed for confirmation of ovulation, representing a distinct methodological advantage over Study 1.

Consistent with Study 1, five day rolling averages (described above) were calculated for estradiol levels, progesterone levels, and all behavioral measures. Daily averages were converted to Z scores based on each participant’s overall mean and standard deviation for each measure across data collection. Five-day rolling averages were used because they minimize random variation in behavioral data due to environmental circumstances (30), reduce the influence of hormone-release pulsatility, and smooth the pattern of hormone variability (31, 32). Again, a minimum of 3 data points were needed to calculate a rolling average value. Only 1% of saliva samples and 1% of behavioral questionnaires were missing across the entire 65-day study period. However, these rates of missing data only resulted in a missing rolling average value on three occasions for the behavioral variables and on one occasion for the saliva samples across all participants. Thus, rates of missing data were very low in this sample. Correlations between Z scores for daily hormones (i.e., estradiol, progesterone) and disordered eating measures (i.e., drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint) were calculated separately for each participant. Initial analyses consisted of partial correlations that controlled for the effect of the other hormone (i.e., progesterone in correlations between estradiol and disordered eating, estradiol in correlations between progesterone and disordered eating). Next, in order to examine the potential contributions of third variables (i.e., negative affect, emotional eating) to hormone-disordered eating relationships, partial correlations that controlled for the other hormone, levels of negative affect, and levels of emotional eating were calculated. These analyses helped understand whether ovarian hormones have direct effects on disordered eating symptoms and/or whether relationships are mediated by negative affect and emotional eating.

Within subject, partial correlations were converted to Fisher’s Z scores and combined across participants. The combined Fisher Z score was converted back to a Pearson correlation to provide an overall effect size for each hormone-behavior relationship (33). To determine the significance of each effect, one-tailed significance levels from partial correlation analyses were converted to Z scores and assigned a negative value if the direction of effect was opposite to the predicted direction. Adjusted Z scores were summed and divided by the square root of the number of participants and converted back to a significance level for the overall effect. These analyses represent combined correlation effect sizes and significance levels from within-subject partial correlation analyses, and advantages of this approach include providing interpretable effect sizes for hormone-behavior associations.

One potential drawback of Study 2 was the use of a twin sample, resulting in a non-independent data structure. Although the non-independence of these observations could be addressed using multi-level modeling approaches, the small number of twins included in this pilot study makes implementation of these approaches difficult (34). Thus, in data tables, correlations are presented for each individual twin and are organized by family in order to examine both within- and between-family patterns of correlations (see Table 2). These comparisons can help determine if the inclusion of genetically related individuals unduly influenced our results.1

Table 2.

Correlations between ovarian hormones and disordered eating in Study 2.

| Variable | All subjects | Family 1 | Family 2 | Family 3 | Family 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZ | DZ | MZ | MZ | |||||||

| r | p | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | |

| r | ||||||||||

| EDI Drive for Thinness | ||||||||||

| Estradiol | ||||||||||

| Initial Analyses | −.11 | .02 | .01 | −.05 | −.05 | −.32 | −.26 | .57 | −.38 | −.34 |

| Partial Analyses | −.09 | .08 | −.02 | .02 | −.22 | −.45 | −.17 | .43 | −.45 | .22 |

| Progesterone | ||||||||||

| Initial Analyses | .34 | <.001 | .31 | .71 | .36 | −.23 | .52 | .16 | .43 | .23 |

| Partial Analyses | .21 | .001 | .12 | .45 | .26 | −.31 | .47 | .07 | .39 | .19 |

| EDI Body Dissatisfaction | ||||||||||

| Estradiol | ||||||||||

| Initial Analyses | −.24 | .01 | −.23 | .40 | −.79 | −.21 | −.25 | .03 | .35 | −.71 |

| Partial Analyses | −.04 | .42 | .51 | .34 | −.79 | −.25 | −.01 | .11 | .39 | −.38 |

| Progesterone | ||||||||||

| Initial Analyses | .13 | .05 | −.44 | .38 | .51 | −.21 | .32 | .23 | .44 | −.24 |

| Partial Analyses | .15 | .03 | −.55 | .44 | .46 | −.25 | .36 | .26 | .64 | −.31 |

| TFEQ Restraint | ||||||||||

| Estradiol | ||||||||||

| Initial Analyses | −.29 | .03 | −.70 | .06 | .36 | −.46 | .21 | .56 | −.87 | −.75 |

| Partial Analyses | .02 | .88 | −.12 | .30 | .21 | −.47 | .37 | .46 | −.53 | −.37 |

| Progesterone | ||||||||||

| Initial Analyses | .08 | .18 | .10 | .10 | −.04 | −.38 | −.10 | .26 | .46 | .22 |

| Partial Analyses | −.01 | .70 | .52 | −.24 | −.23 | −.40 | −.33 | .20 | .35 | .09 |

Note. Initial analyses controlled for the effect of the other hormone (i.e., progesterone in correlations between estradiol and disordered eating, estradiol in correlations between progesterone and disordered eating). Partial analyses controlled for the effect of the other hormone, negative affect, and emotional eating. EDI = Eating Disorder Inventory. TFEQ = Three Factor Eating Questionnaire.

RESULTS

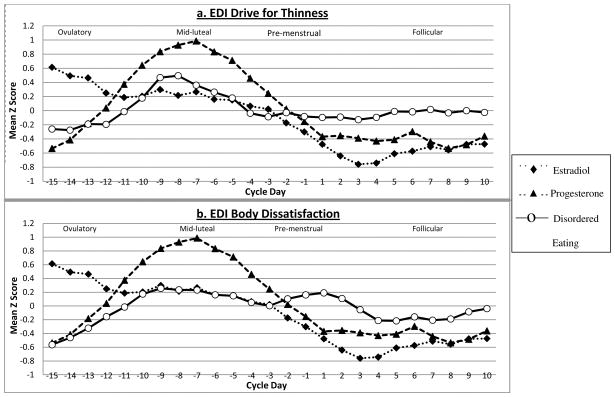

In Study 2, both body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness peaked during the mid-luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (see Figure 2a and b) and exhibited negative associations with levels of estradiol and positive associations with progesterone levels. Importantly, these relationships remained largely unchanged after controlling for the effects of negative affect and emotional eating (see Table 2). The one exception was the association between body dissatisfaction and estradiol levels; this correlation decreased significantly when controlling for negative affect and emotional eating. Post-hoc analyses were conducted to determine if negative affect, emotional eating, or both variables accounted for menstrual cycle associations between body dissatisfaction and estradiol levels. Estradiol-body dissatisfaction associations remained significant when controlling for emotional eating only (partial r = −.18, p = .03), but decreased and became non-significant when controlling for negative affect only (partial r = −.07, p = .08)2. Examination of the pattern of individual correlations for drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction suggests relative consistency in the pattern of effects, both within- and between-families (see Table 2). Indeed, with some exceptions, individual twins exhibited correlations in the same general direction and magnitude as their co-twin, as well as unrelated twins from other pairs.

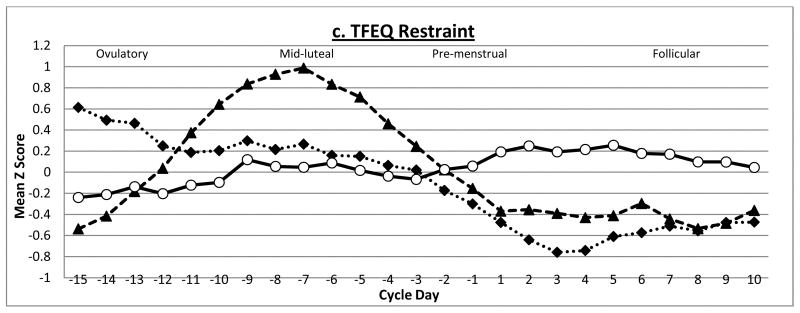

Figure 2. Levels of Estradiol, Progesterone, and Disordered Eating across one Menstrual Cycle in Study 2.

Mean Z scores represent 5-day rolling averages calculated within subjects and then averaged across subjects. Ovulatory phase includes days −15 to −12; Mid-luteal phase includes days −9 to −5; Pre-menstrual phase includes days −3 to +1; Follicular phase includes days +5 to +10. EDI = Eating Disorder Inventory; TFEQ = Three Factor Eating Questionnaire

Findings for dietary restraint were somewhat different. Levels of dietary restraint appeared to exhibit less variation across the menstrual cycle than the other two disordered eating symptoms (see Figure 2c). Moreover, dietary restraint showed significant inverse associations with estradiol across the menstrual cycle, but relationships with progesterone were small and non-significant. Dietary restraint-estradiol associations became non-significant when controlling for the effects of negative affect and emotional eating (see Table 2). Post-hoc analyses indicated that estradiol-dietary restraint relationships were primarily accounted for by emotional eating (partial r = −.10, p = .61), although negative affect also had an effect (partial r = −.17, p =.04). This last set of findings suggests that small changes observed for dietary restraint may be primarily a consequence of changes in the tendency to eat in response to negative emotions than changing hormone levels. This interpretation is supported by the fact that small peaks in dietary restraint are observed during the beginning of menstrual bleeding and the follicular phase which occurs after peak periods of binge eating during the mid-luteal and pre-menstrual phases (2, 3, 10). Relative to drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction, the pattern of individual twin correlations for dietary restraint is less consistent, i.e., twins vary more both within and between families. This may be due to the relative lack of a relationship with ovarian hormones and/or changing levels of negative affect and emotional eating (see above) that appear to impact levels of dietary restraint across the menstrual cycle.

DISCUSSION

Results from Study 2 suggest that both drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction are significantly associated with estradiol and progesterone and that the majority of these effects appear to be direct (i.e., not accounted for by negative affect or emotional eating). Dietary restraint fluctuated less across the menstrual cycle. It exhibited weaker associations with ovarian hormones, and associations that were present appeared to be accounted for by changes in other factors (i.e., negative affect, emotional eating). By assaying daily levels of estradiol and progesterone, this study was able to directly examine longitudinal associations between ovarian hormones and disordered eating symptoms and confirm the presence of ovulation in all participants.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The purpose of our pilot studies was to examine changes in several disordered eating symptoms (i.e., drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint) across the menstrual cycle and to determine whether symptom fluctuations may be related to changing levels of ovarian hormones. Given that ovarian hormones have been implicated in binge eating (2, 3), it was important to understand whether similar effects can be observed for other eating disorder symptoms that are common across the spectrum of eating pathology. Findings for body dissatisfaction and dietary restraint were largely consistent across the two studies. Body dissatisfaction exhibited clear patterns of menstrual cycle fluctuations, and both estradiol and progesterone were significantly associated with body dissatisfaction across the menstrual cycle. Dietary restraint exhibited minimal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle, and ovarian hormones did not directly impact levels of dietary restraint. In contrast, drive for thinness demonstrated much stronger fluctuations across the menstrual cycle in Study 2 as compared to Study 1, and associations between drive for thinness and ovarian hormones were detected in Study 2. Taken together, our findings highlight differential associations between ovarian hormones and disordered eating symptoms and point to potential differences in etiology between these key eating disorder characteristics.

Ovarian hormones exhibited both direct and indirect effects on body dissatisfaction. Progesterone-body dissatisfaction associations were unaffected by negative affect and emotional eating, suggesting that progesterone has direct effects on levels of body dissatisfaction. Indeed, the mean level of body dissatisfaction in the mid-luteal phase, when progesterone is at its peak, did not change significantly after controlling for negative affect and emotional eating in Study 1 or Study 2. The effects of estradiol may be indirect, however, as controlling for negative affect significantly reduced the estradiol-body dissatisfaction correlation in Study 2. This may not be surprising given that negative affect is a strong prospective risk factor for body dissatisfaction (35), and experimentally-induced negative mood increases body dissatisfaction in women (36, 37). Data from our study suggest that high levels of body dissatisfaction observed during the pre-menstrual phase and menstrual bleeding (see Figure 1 and 2b and 13, 14) are likely due to increased negative affect rather than emotional eating or ovarian hormones. This is particularly the case since progesterone is low during menstrual bleeding while levels of negative affect are elevated at this time (38, 39).

Drive for thinness exhibited the most direct relationship with ovarian hormones in Study 2. Hormone-behavior correlations were not significantly reduced after controlling for levels of negative affect or emotional eating, suggesting that associations between ovarian hormones and drive for thinness may be direct (i.e., they are not accounted for by these other potential “third” variables). However, drive for thinness did not exhibit significant menstrual cycle fluctuations in Study 1, particularly after controlling for the effects of negative affect and emotional eating. Given the methodological advantages of Study 2 (i.e., daily assessment of ovarian hormone levels, confirmation of ovulation), it is likely that ovarian hormone-drive for thinness associations exist, particularly since the small cycle fluctuations that were observed in Study 1 were consistent with findings in Study 2. Future research with larger samples is needed to confirm these impressions.

If our results are confirmed and replicated, it will be important for studies to examine potential mechanisms underlying associations between ovarian hormones, body dissatisfaction, and drive for thinness. Anxiety is an interesting candidate in this regard. Drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction can be conceptualized as anxiety driven concerns about one’s body and significant fears of gaining weight or becoming fat. Thus, it may be that associations between ovarian hormone and these disordered eating attitudes are caused by changes in anxiety across the menstrual cycle (40–42). This may be particularly true given that anxiety has been significantly associated with ovarian hormones in both animal and human research. Indeed, experimental evidence suggests that estradiol has anxiolytic effects (43–45), which is consistent with the inverse relationship between estradiol and levels of drive for thinness observed in this study. This relationship was not significantly reduced when controlling for negative affect, but our measure of negative affect (i.e., the PANAS) assesses general negative affectivity rather than anxiety, leaving open the possibility that anxiety may contribute to hormone-drive for thinness associations.

Nonetheless, if associations between ovarian hormones, anxiety, and disordered eating symptoms are present, they are likely to be complex. Progesterone also reduces anxiety in animals (46, 47), a finding opposite to the positive associations between progesterone and both drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction observed in our study. Reasons for the opposing patterns of findings are unclear. It is possible that estradiol influences drive for thinness through its effects on anxiety, but progesterone influences drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction through different mechanisms. Alternatively, associations between progesterone and anxiety may differ in animals and humans, as species-specific effects have been detected for progesterone and other behavioral phenotypes (e.g., binge eating; 48). These possibilities should be examined in future research aimed at understanding the range of mechanisms that may underlie ovarian hormone, drive for thinness, and body dissatisfaction associations in humans.

In comparison to findings for both drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint varied less across the menstrual cycle, and associations with ovarian hormones were more modest. Progesterone-dietary restraint associations were small and non-significant, and estradiol-dietary restraint relationships were accounted for by emotional eating and negative affect. Slight increases in dietary restraint during the follicular phase observed in both studies (see Figures 1 and 2c) may be driven by increases in emotional eating that occur during the mid-luteal and pre-menstrual phases of the menstrual cycle (2, 3, 10, 30). Indeed, ecological momentary assessment studies have found that overeating and binge eating result in increased levels of dietary restraint (49, 50), as individuals may try to compensate for calories ingested by increasing their level of restraint over food intake. Our findings add to this literature by suggesting that changes in dietary restraint across the menstrual cycle appear to be due to changes in negative affect and emotional eating rather than changes in ovarian hormones.

Several limitations of the current study must be acknowledged. Sample sizes for both studies were small, as data were drawn from two pilot studies. However, small samples would be expected to decrease power to detect significant effects, and thus our data my under- rather than over-estimate associations between hormones and disordered eating. Moreover, our use of repeated measures over 35–65 days increased the reliability of our measurements and power to detect significant results. Future studies should replicate our findings to further clarify the role of ovarian hormones in changes in disordered eating symptoms across the menstrual cycle. This is especially the case for drive for thinness given somewhat inconsistent findings between Study 1 and Study 2.

Second, we examined associations within a community sample of women rather than women with diagnosed eating disorders. The symptoms we investigated are strong prospective risk factors for the development of clinical eating disorders (11). Thus, our findings likely contribute to understanding ovarian hormone influences on eating disorder symptoms in clinically significant eating disorders. Additional research with clinical populations is needed to directly examine this possibility.

Third, our use of a twin sample in Study 2 meant that our data were non-independent. This could have artificially increased the correlations between hormones and disordered eating in Study 2. However, results from Study 2 were largely consistent with those in Study 1 (which included unrelated individuals), and inspection of individual twin correlations indicate both within-pair and between family consistency in associations (see Table 2). Thus, while additional research with non-twins is needed to confirm our results, we believe it is unlikely that our use of twins unduly influenced our findings.

Finally, this study was unable to establish with certainty whether ovarian hormones have direct, causal effects on disordered eating symptoms. We did not employ a strict experimental design involving the manipulation of ovarian hormone levels, and we did not examine all possible third variables that could impact hormone-disordered eating associations (e.g., changes in food intake, anxiety, menstrual bloating). However, our longitudinal assessment of participants across the menstrual cycle represents a strong quasi-experimental design, as natural changes in estradiol and progesterone occur in all normally cycling women. Thus, changes in ovarian hormones that precede changes in disordered eating symptoms likely reflect the impact of ovarian hormones on disordered eating rather than the reverse. In addition, the majority of associations remained unchanged after controlling for two important third variables (i.e., negative affect, emotional eating). Taken together, our results represent an important first step in understanding direct and indirect influences of ovarian hormones on levels of drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and dietary restraint that should be examined in greater depth in future work.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MDR-96630) awarded to Ms. Racine, the National Institute of Mental Health (1F31-MH084470) awarded to Ms. Culbert, and the National Institute of Mental Health (1 R01 MH 0820-54) awarded to Drs. Klump, Keel, Sisk, and Burt. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research or the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

To further confirm that the use of twins did not significantly influence our results, we randomly selected 1 twin per pair, 3 separate times, resulting in three samples of 4 twins each. We then recalculated hormone-disordered eating correlations. Despite the significant decrease in sample size, results were highly similar in 2 out of the 3 re-analyses (e.g., estradiol-drive for thinness association: r = −.17, r = −.18), although findings varied somewhat in the third sample (i.e., r = .05). Nonetheless, the majority of the correlations were in line with results from the full sample of twins (i.e., r = −.11).

Given that both drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction varied across the menstrual cycle and were significantly associated with ovarian hormones, we investigated whether results persisted after controlling for the effect of drive for thinness in hormone-body dissatisfaction associations, and the effect of body dissatisfaction in hormone-drive for thinness associations. The pattern of correlations was very similar after controlling for drive for thinness/body dissatisfaction, in that both hormones were associated with drive for thinness, and progesterone was associated with body dissatisfaction (data not shown).

Parts of this manuscript were presented at the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences meeting, Ann Arbor, Michigan, June 3–5, 2010 and the Eating Disorder Research Society meeting, Boston, Massachusetts, October 7–9, 2010.

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors have financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klump KL, Keel PK, Culbert KM, Edler C. Ovarian hormones and binge eating: Exploring associations in community samples. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1749–57. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edler C, Lipson SF, Keel PK. Ovarian hormones and binge eating in bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med. 2007;37:131–41. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hildebrandt T, Alfano L, Tricamo M, Pfaff DW. Conceptualizing the role of estrogens and serotonin in the development and maintenance of bulimia nervosa. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:655–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kemnitz JW, Gibber JR, Lindsay KA, Eisele SG. Effects of ovarian hormones on eating behaviors, body weight, and glucoregulation in rhesus monkeys. Horm Behav. 1989;23:235–50. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(89)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varma M, Chai JK, Meguid MM, Laviano A, Gleason JR, Yang ZJ, Blaha V. Effect of estradiol and progesterone on daily rhythm in food intake and feeding patterns in Fischer rats. Physiol Behav. 1999;68:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarttelin MF, Gorski RA. The effects of ovarian steroids on food and water intake and body weight in the female rat. Eur J Endocrinol. 1973;72:551–68. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0720551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray JM, Wade GN. Food intake, body weight, and adiposity in female rats: Actions and interactions of progestins and antiestrogens. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1981;240:474–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1981.240.5.E474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klump KL, Keel PK, Sisk C, Burt SA. Preliminary evidence that estradiol moderates genetic influences on disordered eating attitudes and behaviors during puberty. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1745–53. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lester NA, Keel PK, Lipson SF. Symptom fluctuation in bulimia nervosa: relation to menstrual-cycle phase and cortisol levels. Psychol Med. 2003;33:51–60. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altabe M, Thompson J. Menstrual cycle, body image, and eating disturbance. Int J Eat Disord. 1990;9:395–401. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carr-Nangle R, Johnson W, Bergeron K, Nangle D. Body image changes over the menstrual cycle in normal women. Int J Eat Disord. 1994:267–273. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199411)16:3<267::aid-eat2260160307>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jappe LM, Gardner RM. Body-image perception and dissatisfaction throughout phases of the female menstrual cycle. Percept Mot Skills. 2009;108:74–80. doi: 10.2466/PMS.108.1.74-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klump KL, Gobrogge KL, Perkins PS, Thorne D, Sisk CL, Breedlove SM. Preliminary evidence that gonadal hormones organize and activate disordered eating. Psychol Med. 2006;36:539–46. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klump KL, Granger DA. The influence of saliva collection method on associations between ovarian hormones and behavior. in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord. 1983;2:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raciti M, Norcross J. The EAT and EDI: Screening, interrelationships, and psychometrics. Int J Eat Disord. 1987;6:579–86. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crowther J, Lilly R, Crawford P, Shepherd K. The stability of the eating disorder inventory. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;12:97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bond MJ, McDowell AJ, Wilkinson JY. The measurement of dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger: an examination of the factor structure of the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:900–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laessle RG, Tuschl RJ, Kotthaus BC, Pirke KM. A comparison of the validity of three scales for the assessment of dietary restraint. J Abnorm Psychol. 1989;98:504–7. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Strien T, Frijters JER, Bergers GPA, Defares PB. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int J Eat Disord. 1986;5:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wardle J. Eating style: a validation study of the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire in normal subjects and women with eating disorders. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31:161–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barr SI, Janelle KC, Prior JC. Energy intakes are higher during the luteal phase of ovulatory menstrual cycles. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:39–43. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klump KL, Burt SA. The Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR): Genetic, environmental and neurobiological influences on behavior across development. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:971–7. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shirtcliff EA, Granger DA, Schwartz EB, Curran MJ, Booth A, Overman WH. Assessing estradiol in biobehavioral studies using saliva and blood spots: simple radioimmunoassay protocols, reliability, and comparative validity. Horm Behav. 2000;38:137–47. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jasienska G, Ziomkiewicz A, Ellison P, Lipson S, Thune I. Large breasts and narrow waists indicate high reproductive potential in women. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;271:1213. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gladis MM, Walsh BT. Premenstrual exacerbation of binge eating in bulimia. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1592–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.12.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kassam A, Overstreet JW, Snow-Harter C, De Souza MJ, Gold EB, Lasley BL. Identification of anovulation and transient luteal function using a urinary pregnanediol-3-glucuronide ratio algorithm. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104:408–13. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waller K, Swan SH, Windham GC, Fenster L, Elkin EP, Lasley BL. Use of urine biomarkers to evaluate menstrual function in healthy premenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:1071–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Essentials of Behavioral Research: Methods and Data Analysis. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. New York: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bearman SK, Martinez E, Stice E, Presnell K. The skinny on body dissatisfaction: A longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35:217–29. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker J, Williamson D, Sylve C. Body image disturbance, memory bias, and body dysphoria: Effects of negative mood induction. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:747–59. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor MJ, Cooper PJ. An experimental study of the effect of mood on body size perception. Behav Res Ther. 1992;30:53–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90096-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutker PB, Libet JM, Allain AN, Randall CL. Alcohol use, negative mood states, and menstrual cycle phases. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1983;7:327–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1983.tb05472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dennerstein L, Burrows G. Affect and the menstrual cycle. J Affect Disord. 1979;1:77–92. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(79)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein JM, Jerram M, Poldrack R, Ahern T, Kennedy DN, Seidman LJ, Makris N. Hormonal cycle modulates arousal circuitry in women using functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9309–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2239-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heitkemper MM, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Burr RL, Hertig V, Bond EF. Symptoms across the menstrual cycle in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:420–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ivey ME, Bardwick JM. Patterns of affective fluctuation in the menstrual cycle. Psychosom Med. 1968;30:336–45. doi: 10.1097/00006842-196805000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walf AA, Frye CA. A review and update of mechanisms of estrogen in the hippocampus and amygdala for anxiety and depression behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1097–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hiroi R, Neumaier JF. Differential effects of ovarian steroids on anxiety versus fear as measured by open field test and fear-potentiated startle. Behav Brain Res. 2006;166:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marcondes FK, Miguel KJ, Melo LL, Spadari-Bratfisch RC. Estrous cycle influences the response of female rats in the elevated plus-maze test. Physiol Behav. 2001;74:435–40. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Picazo O, Fernandez-Guasti A. Anti-anxiety effects of progesterone and some of its reduced metabolites: an evaluation using the burying behavior test. Brain Res. 1995;680:135–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00254-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toufexis DJ, Myers KM, Davis M. The effect of gonadal hormones and gender on anxiety and emotional learning. Horm Behav. 2006;50:539–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klump KL, Suisman JL, Culbert KM, Kashy DA, Sisk CL. The effects of ovarian hormone ablation on binge eating proneness in adult female rats. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas JG. Toward a better understanding of the development of overweight: A study of eating behavior in the natural environment using ecological momentary assessment. Philidelphia: Drexel University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steiger H, Gauvin L, Engelberg MJ, Ying Kin NM, Israel M, Wonderlich SA, Richardson J. Mood- and restraint-based antecedents to binge episodes in bulimia nervosa: Possible influences of the serotonin system. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1553–62. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]