Abstract

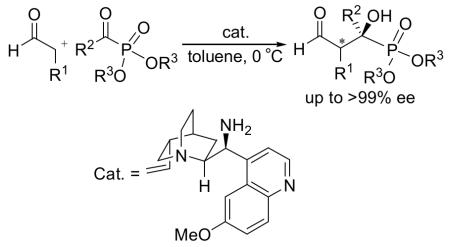

The cross aldol reaction between enolizable aldehydes and α-ketophosphonates was achieved for the first time by using 9-amino-9-deoxy-epi-quinine as the catalyst. β-Formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonates were obtained in high to excellent enantioselectivities. The reaction works especially well with acetaldehyde, which is a tough substrate for organocatalyzed cross aldol reactions. The products were demonstrated to have anticancer activities.

Keywords: ketophosphonate, aldehyde, primary amine, organocatalysis, hydroxyphosphonate

α-Hydroxyphosphonate derivatives are highly biologically active compounds.[1] Previous studies have demonstrated that these compounds have anti-cancer,[2] anti-virus,[3] anti-bacterial[4] and anti-fungal[4] activities. They are also proven inhibitors of such important enzymes as renin[5] and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) protease and polymerase.[6] Due to their relevance to biomedical applications, there have been considerable interests in developing highly enantioselective methods for the synthesis of these compounds in recent years.[7-9] Our own interest[8] in this area led to the development of an organocatalyzed asymmetric synthesis of α-hydroxyphosphonates on the basis a proline derivative-catalyzed cross aldol reaction.[8a,b] Nevertheless, although high enantioselectivities have been achieved in the cross aldol reaction of ketones and α-ketophosphonates by others[9] and us,[8a,b] the cross aldol reaction of enolizable aldehydes and α-ketophosphonates proves to be very difficult.[10] To our knowledge, such a reaction has not been realized so far. Herein we wish to report the first organocatalyzed cross aldol reaction of enolizable aldehydes and α-ketophosphonates for the high enantioselective synthesis of tertiary β-formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonates,[11,12] using a quinine-derived primary amine as the catalyst and the preliminary biological study of these compounds.

Although L-proline and L-prolinamide (compounds 1 and 2, Figure 2) are excellent catalysts for the cross aldol reaction of acetone and α-ketophosphonates,[8a,b] they fail to catalyze the cross aldol reaction between propanal and α-ketophosphonates.[10] After carefully comparing the proposed transition states [8b,e] of these two similar reactions (Figure 1), we believe the reaction failed in the case of propanal because of the unfavorable interactions between the enamine methyl group and the large phosphonate group in the transition state (Figure 1, right structure). Thus, we hypothesized that the reaction should proceed if such unfavorable interactions are alleviated.

Figure 2.

Catalysts Screened for the Cross Aldol Reaction

Figure 1.

Proposed favoured Transition States for the Aldol Reactions of α-Ketophosphonate with Acetone and Propanal

One way to reduce the unfavorable interactions is to use acetaldehyde (9a) as the substrate,[13] since, with 9a, the methyl group in the proposed transition state (Figure 1) will be replaced with a much smaller hydrogen atom (as in the acetone case). Acetaldehyde (9a) and diethyl benzoylphosphonate (10a) were then adopted as the substrates to test our hypothesis, using proline (1) and prolinamide (2) as the catalysts (Figure 2). As shown by the results collected in Table 1, indeed, after reacting in CH2Cl2 at room temperature for a week, the desired aldol product 11a may be obtained in reasonable yields (50% and 59% with L-proline and L-prolinamide, respectively, entries 1 and 2). Diphenylprolinol catalysts 3 and 4 are known to catalyze high enantioselective cross aldol reactions of acetaldehydes;[13a,b,l] however, poorer results were obtained with these two catalysts (entries 3 and 4). Nevertheless, since acetaldehyde is a known tough substrate for organocatalyzed cross aldol reactions,[13a,b,l] we were encouraged by these results even though the enantioselectivities obtained were impractical.

Table 1.

Catalyst Screening and Reaction Condition Optimizations[a]

| Entry | Cata- lyst |

Additive | Solvent | Yield (%)[b] |

ee (%)[c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | none | CH2Cl2 | 50 | 9 |

| 2 | 2 | none | CH2Cl2 | 59 | 13 |

| 3 | 3 | PhCO2H[d] | CH2Cl2 | 11 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 | PhCO2H[d] | CH2Cl2 | 9 | 10 |

| 5 | 5 | none | CH2Cl2 | 0 | - |

| 6 | 6 | PhCO2H[e] | CH2Cl2 | 49 | 6 |

| 7 | 7 | PhCO2H | CH2Cl2 | 45 | 17 |

| 8 | 8 | PhCO2H | CH2Cl2 | 46 | 57 [f] |

| 9 | 8 | CH3CO2H | CH2Cl2 | 30 | 71[f] |

| 10 | 8 | EtCO2H | CH2Cl2 | 39 | 74[f] |

| 11 | 8 | CF3CO2H | CH2Cl2 | 23 | 41[f] |

| 12 | 8 | p-TsOH | CH2Cl2 | 0 | - |

| 13 | 8 | MBA[g] | CH2Cl2 | 46 | 75[f] |

| 14 | 8 | MBA[g] | THF | 51 | 86[f] |

| 15 | 8 | MBA[g] | CH3CN | 38 | 77[f] |

| 16 | 8 | MBA[g] | hexane | 45 | 84[f] |

| 17 | 8 | MBA[g] | benzene | 53 | 83[f] |

| 18 | 8 | MBA[g] | toluene | 53 | 91[f] |

| 19[g] | 8 | MBA[g] | toluene | 75 | 93[f] |

Unless otherwise specified, all reactions were carried out with 10a (0.30 mmol) and 9a (1.5 mmol) in the specified solvent (2.0 mL) with the amine catalyst (10 mol %) and the acid cocatalyst (30 mol %) at rt for 7 days.

Yield of isolated product after column chromatography.

Determined by HPLC analysis on a ChiralCel OJ-H column.

The loading of the acid cocatalyst was 10 mol %.

The loading of the acid cocatalyst was 20 mol %.

The opposite enantiomer was obtained.

4-Methoxylbenzoic acid.

Carried out at 0 °C.

Another way to solve the aforementioned problem is to use a different catalyst, because the transition state is known to be dependent on the catalyst structure and the catalysis mechanism. In this regard, we were very interested in primary amine catalysts,[14] since primary amines would lead to less crowded transition states.[14a] Thus, we screened several primary amines as the catalyst for the cross aldol of 9a and 10a (5-8, Figure 2). The results are also collected in Table 1. Among these catalysts, L-phenylalanine (5) is not effective at all as no desired product could be obtained after the reaction (entry 5). Nonetheless, in the presence of benzoic acid as the cocatalyst, (S,S)-1,2-diphenyl-1,2-ethanediamine (6) gave the expected product 11a in 49% yield and 6% ee (entry 6). Catalysts 7 and 8, derived from quinidine, and quinine, respectively, have been used by List co-workers as the catalyst in an intramolecular aldol reaction;[14a] however, to our knowledge, they have never been used in an intermolecular aldol reaction. When 7 was used as the catalyst with benzoic acid as the cocatalyst, the expected 11a was obtained in 45% yield and 17% ee (entry 5). The ee value was improved to 57% ee when compound 8 was applied (entry 6). Since catalyst 8 leads to highest ee value of the product, it was selected for further optimizations. Firstly, several acid cocatalysts were screened, and it was found that aliphatic acids, such as acetic acid and propoinic acid, led to improved ee values of the product (71% and 74%, respectively, entries 9 and 10); however, the yields of the product were lower. In contrast, stronger acids, such as trifluoroacetic acid and toluenesulfonic acid, are not effective (entries 11 and 12). Additional screening identified 4-methoxybenzoic acid as the best cocatalyst, as the highest ee value of 75% was obtained in a reasonable yield (46%, entry 13). Then the solvent effects were evaluated (entries 14-18), and toluene was identified as the best solvent for this reaction, because the product 11a could be obtained in 53% yield with a high ee value of 91% with this solvent (entry 16). Further optimization of the reaction temperature revealed that an improved yield of 75% of the desired product could be obtained at 0 °C, with also a slightly improved ee value of 93% (entry 17). The improved product yield at this temperature was probably due to reduced competing reactions. Further dropping the reaction temperature, however, leads to inferior reaction yield without improvement in the ee value (data not shown). It should be pointed out that the major enantiomer obtained with catalyst 8 is opposite that of the rest catalysts.

Next the scope of this reaction was evaluated with different α-ketophosphonate and aldehyde substrates. The results are presentedin Table 2. As shown in Table 2, the size of the ester alkyl groups in the phosphonate has almost no influence on the enantioselectivity of this reaction, as similar ee values were obtained for the methyl, ethyl and isopropyl esters (entries 1-3). The same is true with the electronic nature of the substituents on the phenyl ring of the benzoylphosphonates: Excellent ee values were obtained for both electron-withdrawing and electron-donating substituents (entries 4-9).

Table 2.

Enantioselective Synthesis of β-Formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonates [a]

| En- try |

R1 | R2 | R3 |

t (d) |

Yield (%)[b] |

ee (%)[c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | Ph | Me | 8 | 11b /67 | 96 |

| 2 | H | Ph | Et | 7 | 11a /75 | 93 |

| 3 | H | Ph | i-Pr | 5 | 11c / 67 | 96 |

| 4 | H | 4-FC6H4 | Et | 7 | 11d /61 | 99 |

| 5 | H | 4-ClC6H4 | Et | 7 | 11e /62 | 94 |

| 6 | H | 4-BrC6H4 | Et | 7 | 11f /55 | >99 |

| 7 | H | 4-IC6H4 | Et | 7 | 11g /54 | 95[d] |

| 8 | H | 4-MeC6H4 | Et | 6 | 11h /67 | 96 |

| 9 | H | 4-MeOC6H4 | Et | 7 | 11i /66 | 92[d] |

| 10 | H | 2-ClC6H4 | Et | 5 | 11j /35 | 96 |

| 11 | H | 3-ClC6H4 | Et | 7 | 11k /67 | 93[d] |

| 12 | H | 3-ClC6H4 | Me | 7 | 11l /60 | 97 |

| 13 | Me | Ph | Et | 9 | 11m/44 | 68 [[e],[f]] |

All reactions were carried out with α-ketophosphonate 10 (0.30 mmol) and aldehyde 9 (1.50 mmol) in dry toluene (2.0 mL) with catalyst 8 (0.03 mmol, 10 mol %) and 4-methoxybenzoic acid (0.09 mmol, 30 mol %) at 0 °C.

Yield of isolated product after column chromatography.

Unless otherwise specified, ee values were determined by chiral HPLC analyses on a ChiralCel OJ-H column.

Determined by chiral HPLC analyses on a ChiralPak AD-H column.

Value of the major diastereomer. The ee value of the minor enantiomer was 73%.

The dr was 7:5 (1H NMR analysis of the crude product); the Me and OH groups have anti configuration in the major diastereomer as determined by NOE experiments.

Benzoylphosphonate with an ortho-chloro substituent is less reactive and the yield obtained was much lower (entry 10), which is most probably due to steric reasons. However, as shown in Table 2, the position of the substituent on the phenyl ring has almost no influence on the enantioselectivity (entries 5, 10-12). Propanal, which has failed with other catalysts, also participates in the reaction under these new conditions, and the reaction yielded the desired product in 44% yield as a diastereomeric mixture (dr 7:5), with ee values of 68% and 73% for the major and minor diastereomers, respectively (entry 13). The methyl and hydroxy groups in the major diastereomer was determined to be anti by NOE experiments.

The fact that all the products obtained in this study are liquid makes the direct determination of the absolute configuration of major enantiomer obtained in this reaction difficult. To determine the absolute configuration of the major enantiomer, compound 11f was converted to its 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone derivative 12 (Figure 3), and its stereochemistry at the quaternary stereogenic center was successfully determined to be R by X-ray crystallography.16 Thus, the absolute configuration of compound 11f was assigned as R. On the basis of these results, a tentative mechanism is proposed to account for the formation of the major enantiomer in this reaction (Figure 4). The attack of the enamine on the si face of the hydrogen-bound α-ketophosphonate gives the expected R-enantiomer.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone derivative 12

Figure 4.

Proposed transition states for the formation of the major enantiomer (A− = 4-methoxybenzoate)

It is well known that α-hydroxyphosphonate derivatives are biologically active molecules. However, the biological activities of β-formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonates are still unknown. To assess their biological activities, we conducted some preliminary biological assays of these compounds. Thus, human immortalized Foreskin Fibroblasts (HFF) and ovarian cancer cells (ID8) were first incubated for 24 h, then the screened compounds was added in the indicated amount and the cells were further incubated for another 48 h. Cell proliferation was assessed by MTT assay as described previously and the results are presented in Figure 5.15

Figure 5.

Inhibitory effect of the screened compounds on cell proliferation. [The results were expressed as percentage of the control (DMSO controls set at 100%). Data are given as means ± SEM, *, p<0.05 (Student’s t-test)]15 (II-SP-72 is 11h; I-VKN-81 is compound 11a; I-VKN-97 is compound 11f)

As shown in Figure 5, β-formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonate derivatives, II-SP-72 (11h), I-VKN-81 (11a) and I-VKN-97 (11f), significantly inhibited the proliferation of immortalized cell line HFF and ovarian cancer cell line ID8 in a dose-dependent manner (from 1 to 100 μM). In contrast, a similar α-hydroxyphosphonate derivative that does not contain an aldehyde group, I-ZCG-1 (Figure 6), displays only minor antiproliferative activity at a high concentration (100 μM). Interestingly, I-VKN-97 preferentially inhibited ID8 cancer cells rather than HFF immortalized cells. Moreover, antiproliferative effects of II-SP-72, I-VKN-81 and I-VKN-97 on other human (SKOV3 and K562) and murine tumour cells (B16F10) were also observed (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Structure of I-ZCG-1

In summary, we have developed the first cross aldol reaction of enolizable aldehydes and α-ketophosphonates for the highly enantioselective synthesis of tertiary β-formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonates. The reaction utilizes a quinine-derived primary amine as the catalyst, and excellent enantioselectivities were achieved for the cross aldol products of acetaldehyde, which is unprecedented for such primary amine catalysts. Preliminary screen of some of the β-formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonate products indicates the products can suppress the proliferation of human and murine tumour cells, while are mild against immortalized cells (HFF).

Experimental Section

Typical Procedure for the Aldol Reaction

To a stirred solution of p-methoxybenzoic acid (13.7 mg, 0.09 mmol, 30 mol %) and quinine-derived amine 8 (9.7 mg, 0.03 mmol, 10 mol %) in toluene (2.0 mL) were added the α-ketophosphonate (0.30 mmol) and the aldehyde (1.5 mmol) at 0 °C. After the completion of reaction (monitored by TLC), the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to yield the crude product, which was purified by column chromatography over silica gel (7:3 ethyl acetate/hexane) to furnish the desired β-formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonate as a pure compound.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The generous financial support of this project from the NIH-NIGMS (Grant no. SC1GM082718) and the Welch Foundation (Grant No. AX-1593) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also thank Dr. Sampak Samanta for performing some initial experiments. The authors also thank Dr. Sampak Samanta for performing some initial experiments, Dr. William Haskins and the RCMI Proteomics Core (NIH G12 RR013646) at UTSA for assistance with HRMS analysis, and Dr. Arman Hadi for performing X-ray analysis of compound 11f.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adsc.200######.

References

- [1].For reviews, see: Kolodiazhnyi OI. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:3295–3340. Stawinski J, Kraszewski A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002;35:952–960. doi: 10.1021/ar010049p.

- [2].a) Peters ML, Leonard M, Licata AA. Clev. Clin. J. Med. 2001;68:945–951. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.68.11.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee MV, Fong EM, Singere FR, Guenette RS. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2602–2608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Leder BZ, Kronenberg HM. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:866–869. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.17841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Snoeck R, Holy A, Dewolf-Peeters C, Van Den Oord J, De Clercq E, Andrei G. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3356–3361. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3356-3361.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kategaonkara AH, Pokalwara RU, Sonara SS, Gawalib VU, Shingatea BB, Shingare MS. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:1128–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Tao M, Bihovsky R, Wells GJ, Mallamo JP. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:3912–3916. doi: 10.1021/jm980325e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dellaria JF, Jr., Maki RG, Stein HH, Cohen J, Whittern D, Marsh K, Hoffman DJ, Plattner JJ, Perun TJ. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:534–542. doi: 10.1021/jm00164a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Stowasser B, Budt K-H, Li J-Q, Peyman A, Ruppert D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6625–6628. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Suyama K, Sakai Y, Matsumoto K, Saito B, Katsuki T. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:809–811. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905158. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:797–799. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905158. Gondi VB, Hagihara K, Rawal VH. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:790–793. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804244. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:776–779. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804244. Abell JP, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10521–10523. doi: 10.1021/ja803859p. Huang J, Wang J, Chen X, Wen Y, Liu X, Feng X. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:287–294. Chen X, Wang J, Zhu Y, Shang D, Gao B, Liu X, Feng X, Su Z, Hu C. Chem.-Eur. J. 2008;14:10896–10899. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801958. Pawar VD, Bettigeri S, Weng S-S, Kao J-Q, Chen C-T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6308–6309. doi: 10.1021/ja060639o. Nesterov V, Kolodyazhnyi OI. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2005;75:1161–1162. Skropeta D, Schmidt RR. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:265–723. Rowe BJ, Spilling CD. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2001;12:170–1708. Cermak DM, Du Y, Wiemer DF. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:388–393. Pogatchnik DM, Wiemer DF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:3495–3498. Meier C, Laux WHG. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1996;7:89–94. Arai T, Bougauchi M, Sasai H, Shibasaki M. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:2926–2927. doi: 10.1021/jo960180o.

- [8].a) Samanta S, Zhao C-G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7442–7443. doi: 10.1021/ja062091r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dodda R, Zhao C-G. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4911–4914. doi: 10.1021/ol062005s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Mandal T, Samanta S, Zhao C-G. Org. Lett. 2007;9:943–945. doi: 10.1021/ol070209i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Samanta S, Perera S, Zhao C-G. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:1101–1106. doi: 10.1021/jo9022099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].For recent examples of asymmetric synthesis on the basis of organocatalyzed cross aldol reactions, see: Jiang J, Chen X, Wang J, Hui Y, Liu X, Lin L, Feng X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:4355–4357. doi: 10.1039/b917554g. Liu J, Yang ZG, Wang Z, Wang F, Chen XH, Liu XH, Feng XM, Su ZS, Hu CW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5654–5655. doi: 10.1021/ja800839w.

- [10].The attempted cross aldol reaction of propanal and benzoylphosphonate failed, see: Samanta S, Krause J, Mandal T, Zhao C-G. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2745–2748. doi: 10.1021/ol071097y.

- [11].The synthesis of racemic β-formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonates has not been systemically studied; for examples, see: Haeltersa J-P, Couthon-Gourvèsa H, Le Goffa A, Simona G, Corbela B, Jaffrè P-A. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:6537–6543. Guanti G, Zannetti MT, Banfi L, Riva R. Adv. Syn. Catal. 2001;343:682–691.

- [12].For an example of enzymatic resolution of secondary β-formyl-α-hydroxyphosphonates, see reference 11b.

- [13].Acetaldehyde has been seldom used in organocatalyzed cross aldol reactions, for examples, see: Hayashi Y, Itoh T, Aratake S, Ishikawa H. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:2112–2114. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704870. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2082–2084. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704870. Hayashi Y, Samanta S, Itoh T, Ishikawa H. Org. Lett. 2008;10:5581–5583. doi: 10.1021/ol802438u. For examples of cross aldol reactions with isatins, see: Chen W-B, Du X-L, Cun L-F, Zhang X-M, Yuan W-C. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:1441–1446. Itoh T, Ishikawa H, Hayashi Y. Org. Lett. 2009;11:3854–3857. doi: 10.1021/ol901432a. Hara N, Nakamura S, Shibata N, Toru T. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:6790–6793. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900944. For application of acetaldehyde in other organocatalyzed reactions, see: Yang JW, Chandler C, Stadler M, Kampen D, List B. Nature. 2008;452:453–455. doi: 10.1038/nature06740. García-García P, Ladépêche A, Halder R, List B. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:4797–4799. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800847. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4719–4721. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800847. Hayashi Y, Itoh T, Ohkubo M, Ishikawa H. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:4800–4802. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801130. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4722–4724. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801130. Hayashi Y, Okano T, Itoh T, Urushima T, Ishikawa H, Uchimaru T. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:9193–9198. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802073. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:9053–9058. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802073. Kano T, Yamaguchi Y, Maruoka K. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:1870–1872. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805628. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:1838–1840. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805628. Chandler C, Galzerano P, Michrowska A, List B. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:2012–2014. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806049. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:1978–1980. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806049. For a review, see: Alcaide B, Almendros P. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:4710–4712. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801231. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4632–4634. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801231.

- [14].For selected examples of primary amine-catalyzed enantioselective reactions involving an enamine or iminium intermediate, see: Zhou J, Wakchaure V, Kraft P, List B. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:7768–7771. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802497. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:7656–7658. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802497. Martin NJA, List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13368–13369. doi: 10.1021/ja065708d. Lu X, Liu Y, Sun B, Cindric B, Deng L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8134–8135. doi: 10.1021/ja802982h. Wang X, Reisinger CM, List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6070–6071. doi: 10.1021/ja801181u. McCooey SH, Connon SJ. Org. Lett. 2007;9:599–602. doi: 10.1021/ol0628006. Liu T-Y, Cui H-L, Zhang Y, Jiang K, Du W, He Z-Q, Chen Y-C. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3671–3674. doi: 10.1021/ol701648x. Zheng B-L, Liu Q-Z, Guo C-S, Wang X-L, He L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:2913–2915. doi: 10.1039/b711164a. Reisinger CM, Wang X, List B. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:8232–8235. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8112–8115. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803238. Bartoli G, Melchiorre P. Synlett. 2008:1759–1772. Chen Y-C. Synlett. 2008:1919–1930. Gogoi S, Zhao C-G, Ding D. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2249–2252. doi: 10.1021/ol900538q. Mandal T, Zhao C-G. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:7828–7831. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:7714–7717. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803236. Xie J-W, Chen W, Li R, Zeng M, Du W, Yue L, Chen Y-C, Wu Y, Zhu J, Deng J-G. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:393–396. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:389–392. Huang H, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7170–7171. doi: 10.1021/ja0620890. For a review on primary amine catalysis, see: Peng F, Shao Z. J. Mol. Catal. A. 2008;285:1–13. For a review on cinchona alkaloid catalysis, see: Song CE, editor. Cinchona Alkaloids in Synthesis and Catalysis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2009.

- [15].Jin D, Fan J, Wang L, Thomson LF, Liu A, Daniel BJ, Shin T, Curiel TJ, Zhang B. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2245–2255. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].CCDC no. 820954 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for 12. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. For the ORTEP drawing of compound 12, please see Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.