Abstract

Plants generate effective responses to infection by recognizing both conserved and variable pathogen-encoded molecules. Pathogens deploy virulence effector proteins into host cells, where they interact physically with host proteins to modulate defense. We generated a plant-pathogen immune system protein interaction network using effectors from two pathogens spanning the eukaryote-eubacteria divergence, three classes of Arabidopsis immune system proteins and ~8,000 other Arabidopsis proteins. We noted convergence of effectors onto highly interconnected host proteins, and indirect, rather than direct, connections between effectors and plant immune receptors. We demonstrated plant immune system functions for 15 of 17 tested host proteins that interact with effectors from both pathogens. Thus, pathogens from different kingdoms deploy independently evolved virulence proteins that interact with a limited set of highly connected cellular hubs to facilitate their diverse life cycle strategies.

Introduction

Interactions between disease causing microbes and their hosts are complex and dynamic. Plants recognize pathogens through two major classes of receptors. Initially, plants sense microbes via perception of conserved Microbe-Associated Molecular Patterns (MAMPs) by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) located on the cell surface. This first level of recognition results in MAMP-triggered immunity (MTI), which is sufficient to fend off most microbes (1). To counter MTI, evolutionarily diverse groups of plant pathogens independently evolved mechanisms to secrete and deliver effector proteins into host cells (2, 3). Effectors interact with cellular host targets, and modulate MTI and/or host metabolism in a manner conducive to pathogen proliferation and dispersal (3–5). Plants deploy a second set of polymorphic intracellular immune receptors to recognize specific effectors. Nearly all are members of the nucleotide binding site-leucine rich repeat (NB-LRR) protein family, analogous to animal innate immune NLR proteins (6, 7). NB-LRR proteins can be activated upon direct recognition of an effector, or indirectly by the action of an effector protein on a specific host target (3–5). NB-LRR activation causes Effector-Triggered Immunity, or ETI, essentially a high amplitude MTI response that results in robust disease resistance responses that often include localized host cell death and systemic defense signaling (3, 5).

We systematically mapped physical interactions between proteins from the reference plant Arabidopsis thaliana (hereafter Arabidopsis) and effector proteins from two pathogens: the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas syringae (Psy) and the obligate biotrophic oomycete Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa). These two pathogens last shared a common ancestor over one billion years ago and use vastly different mechanisms to colonize plants. Despite independent evolution of virulence mechanisms, we hypothesized that these two pathogens would deploy effectors to manipulate a largely overlapping set of core cellular MTI machinery (4, 5).

Mapping of a plant-pathogen protein-protein interactome network

We used experimentally validated Psy effector proteins (8), candidate effectors from Hpa (9, 10), and immune-related Arabidopsis proteins or “immune proteins” including: i) N-terminal domains of NB-LRR intracellular immune receptors; ii) cytoplasmic domains of LRR-containing receptor like kinases (RLKs), a subclass of PRRs; and (iii) known signaling components or targets of pathogen effectors (defense proteins) (fig. S1, table S1, 10). We mapped binary protein-protein interactions between these 552 immune and pathogen proteins and the ~8,000 full-length Arabidopsis proteins (AtORFeome2.0) used to generate the Arabidopsis Interactome, version 1 (AI-1) using the same yeast two-hybrid-based pipeline (10–12). This resulted in an experimentally determined plant-pathogen immune network containing 1,358 interactions among 926 proteins, including 83 pathogen effectors, 170 immune proteins, and 673 other Arabidopsis proteins (hereafter ‘immune interactors’) (Fig. 1A, table S2, 10). Because our dataset was acquired using the same pipeline as that used to define AI-1 (11), we estimate that the two datasets are equivalent in quality with: i) a coverage of ~16% of all possible interactions within the tested space (fig. S1); and ii) a proportion of true biophysical interactions statistically indistinguishable from that of well-documented high-quality pairs from the literature (11). We combined our dataset with interactions from AI-1 and literature-curated interactions (LCI; 11) involving the same 926 proteins. This resulted in a ‘plant-pathogen immune network, version 1’ (PPIN-1) containing 3,148 interactions (fig. S2, table S2).

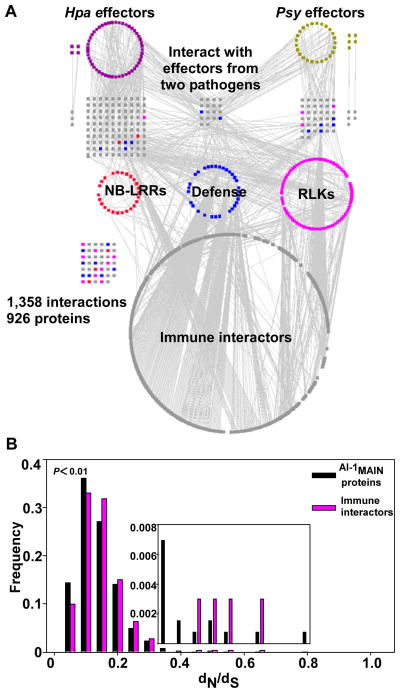

Fig. 1. Construction of a high-quality plant-pathogen immune network, version 1 (PPIN-1).

(A). Experimentally determined plant-pathogen immune network. Proteins (nodes) are color coded as P. syringae effectors (Psy; gold), H. arabidopsidis effectors (Hpa; purple), plant proteins including literature-curated defense proteins (blue), N-terminal domains of NB-LRR immune receptors (red), cytoplasmic domains of LRR-containing receptors like kinase (RLK), a subclass of pattern recognition receptors (pink) and “immune interactors” (grey). Grey edges represent protein-protein interactions. Interactions that are not connected to the network involving Hpa or Psy effectors are indicated next to their relevant protein categories in the first and second layers. Grid at left denotes individual interactions involving immune proteins. (B) PPIN-1 proteins evolve faster than those of AI-1. Distribution of dN/dS ratios computed between Arabidopsis proteins and their Papaya orthologs for all AI-1MAIN proteins and for immune interactors (from A) present in AI-1MAIN. Inset is rescaled on the Y-axis to make the higher dN/dS categories more apparent. The X-axis remains the same for the inset. P-value: Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Fig. 1, fig. S2 and an interactive web interface (http://signal.salk.edu/interactome/PPIN1.html) display PPIN-1 in four layers (Fig. 1A: the experimentally determined network; fig. S2: the derived PPIN-1). The top layer contains effector proteins from both pathogens; the second layer consists of host proteins directly interacting with those effectors (‘effector targets’); the third layer depicts the three previously defined classes of Arabidopsis immune proteins: NB-LRR, defense and RLK proteins; and the fourth layer consists of immune interactors.

Of the 673 immune interactors, only 66 were among the 975 proteins encoded by ORFs in AtORFeome2.0 with a Gene Ontology (GO) annotation related to immunity (‘GO-immune proteins’; table S3) (P > 0.05, table S4). This may be due to the technical limitations of both large- and small-scale experiments (12–15) and limited knowledge about the plant immune system. While 239 of the 673 immune interactors interacted with a GO-immune protein in the systematically mapped subset of AI-1 termed AI-1MAIN (see Glossary; 10, 11), 368 were neither GO-immune proteins nor previously known to interact with a GO-immune protein (fig. S3).

We identified 165 putative effector targets in PPIN-1, compared to ~20 described previously (16). While the functions of most of these Arabidopsis proteins is unknown, they are enriched in GO annotations for regulation of both transcription and metabolism, and nuclear localization (table S5; 10). We noted significant enrichment of the effector targets in immune- and hormone-related GO-annotations (table S4; 10, 17). Angiosperm-specific proteins are overrepresented among the effector targets, in comparison to all proteins encoded in AtORFeome2.0 (hypergeometric P = 0.0007; table S4).

To characterize the transcriptional response of genes encoding proteins in PPIN-1, we categorized all corresponding proteins into 10 non-overlapping groups (table S6): two immune protein groups (the two combined classes of receptors and the defense proteins); one group containing all effector proteins; and seven groups containing subsets of the immune interactors corresponding to their pattern of interactions with the three aforementioned groups (fig. S4, fig. S5, table S7; 10). Many receptor genes were differentially regulated under a variety of defense-related conditions (fig. S5); however genes encoding specific interactors of these receptors were not (fig. S4, fig. S5, table S7). This suggests that pathogen detection sensitivity is specifically modulated via transcriptional regulation of receptor genes (18, 19). Receptors might also associate with proteins unrelated to the defense machinery.

PPIN-1 proteins evolve faster than those of AI-1

The LRR domains of both plant immune receptor classes exhibit footprints of positive diversifying selection (3, 20). Host-pathogen ‘arms races’ are assumed to drive adaptive evolution of immune system genes, though this is an over-simplification for plant-pathogen interactions (21). We defined a set of 333 Arabidopsis genes with one-to-one orthology relationships in Papaya (10) as a reference, and estimated the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous mutations per site in their coding sequences (dN/dS) (Fig. 1B). Non-receptor immune interactors are evolving very slowly overall, suggesting functional constraint and purifying selection. They nevertheless exhibit a significantly higher evolution rate than proteins in AI-1MAIN (P < 0.01; Fig. 1B, 10). This was not the case for control gene groups encoding hormone-related proteins (fig. S6A; 17) or metabolic enzymes (fig. S6B; 22, 23). Hence, even the non-receptor proteins from PPIN-1 evolve faster than other protein groups or the proteins in AI-1MAIN in general.

Pathogen effectors converge onto highly connected proteins in the plant interactome

Our hypothesis was that many effectors from evolutionarily diverse pathogens would converge onto a limited set of defense related host targets and molecular machines (4, 5), as opposed to each effector having evolved to target idiosyncratic, pathogen life-style-specific targets. To test this, we compared the number of effector targets identified in PPIN-1 to the number of targets expected with randomly assigned connections between effectors and Arabidopsis proteins (‘random targets’). PPIN-1 defined 165 direct effector targets; 18 of these were targeted by effectors from both pathogens (Fig. 1A, fig. 7A, left, fig. S8, left; 10). In contrast, simulations identified an average of 320 random targets, of which less than 1% would be targeted by effectors from both pathogens (P < 0.001, empirical p-value, Fig. 2A, fig. S7A, fig. S8; 10). We investigated the connectivity between the 137 observed effector targets that are also present in AI-1MAIN. They are connected by 139 interactions in AI-1MAIN (P < 6.7 × 10−5, empirical p-value; Fig. 2B, table S8), whereas we expect an average of only 22 (maximum 59) connections if effector targets were randomly distributed in a network with the same structure as AI-1MAIN (Fig. 2B, fig. S7B). Collectively, these data support our hypothesis that diverse pathogens deploy virulence effectors that converge onto a limited set of host cellular machines.

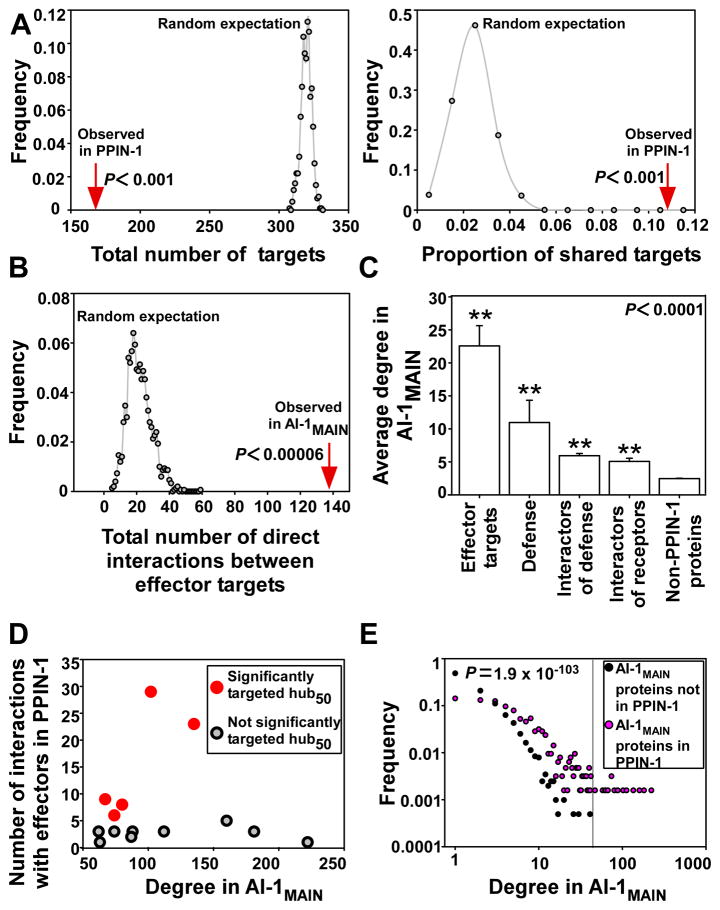

Fig. 2. Effector proteins converge onto interconnected cellular hubs.

(A) Significance of the convergence of effectors onto a limited set of targets. Distribution of the total number of effector targets (left panel) and of the proportion of shared targets (right panel) in 1,000 simulations (10). The red arrows represent the observed number of effector targets in PPIN-1 (left panel; Fig. 1A, Fig. 3A, fig. S7, fig. S8) and the observed proportion of shared targets in PPIN-1 (right panel; Fig. 1A, Fig. 3A, fig. S7 fig. S8,). (B) Significance of the connectivity among effector targets. Distribution of the number of direct connections between effector targets in 15,000 simulations (10). The red arrows represent the observed number of interactions between effector targets in AI-1MAIN. (C) PPIN-1 proteins display a high connectivity in AI-1MAIN. The average degree (number of interactors) in AI-1MAIN of PPIN-1 proteins groups (Fig. 1A) was compared to proteins in AI-1MAIN that are not in PPIN-1. All groups of proteins from PPIN-1 have a significantly higher degree than non-PPIN-1 proteins in AI-1MAIN (**P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U-test). Receptors include both NB-LRRs and RLKs. Error bars: standard error of the mean. (D) Five hubs50 are targeted by significantly more effectors than expected given their degree in AI-1MAIN. Each dot represents a hub50 targeted by at least one effector in PPIN-1, graphed as a function of both its degree in AI-1MAIN (X axis) and of the number of interactions it has with effectors in PPIN-1 (Y axis). Dots colored red correspond to hubs50 that are targeted by significantly more effectors than expected given their degree (P < 0.05, empirical P-value from degree preserving random simulations (10)). (E) Relative frequency of degree in AI-1MAIN of: (i) the 632 PPIN-1 proteins present in AI-1MAIN (pink); and (ii) the remaining 2,029 proteins in AI-1MAIN (black). Group (i) shows a significantly higher degree distribution than group (ii); Mann-Whitney U-test (P = 1.9 × 10−103). The vertical line corresponds to a degree of 50.

Scale-free networks are resilient to random perturbations, but sensitive and easily destabilized by targeted attack on their most highly connected hubs (24). AI-1MAIN shares this property even though it is not perfectly scale-free (fig. S9)Simulations demonstrate that an attack on experimentally identified effector targets is much more damaging to the network structure than an attack on the same number of randomly selected proteins (fig. S9). Consistent with this, we found that the number of interaction partners (degree) of the effector targets present in AI-1MAIN was significantly higher than that of proteins in AI-1MAIN that are not in PPIN-1 (Fig. 2C). Remarkably, 7 of the 15 hubs of degree greater than 50 (hubs50) in AI-1MAIN were targeted by effectors from both pathogens (P = 6.5 × 10−13; table S4, table S8), and 14 of the 15 hubs50 were targeted by effectors from at least one pathogen (P = 6.9 × 10−18; table S4, table S8; 10), consistent with observations of human-virus infection systems (25–28).

We evaluated whether this connectivity explains the observed convergence (Fig. 2, A, fig. S8). We performed simulations where the probability of an Arabidopsis protein to randomly interact with an effector was proportional to its degree in AI-1MAIN. We found that 51 of 2,661 AI-1MAIN proteins were actually targeted significantly more often by effectors than expected given their respective degrees (e.g. “significant targets”; table S8). These include five of the 14 hubs50 that interact with effectors (P = 5 × 10−6; Fig. 2D, table S4), and four of the seven hubs50 that are targeted by effectors from both pathogen species (P = 0.006; table S4). Among the 17 proteins interacting with effectors from both pathogens that are also present in AI-1MAIN, 12 are significant targets (P = 0.003; table S4). These results indicate that the convergence of effectors onto a set of host targets cannot be explained merely by the high connectivity of those targets, and thus likely reflects additional aspects of the host-pathogen co-evolution history.

In addition to effector targets, other PPIN-1 proteins displayed high connectivity in AI-1MAIN (Fig. 2, C and E). Consequently, immune interactors form a highly connected cluster in the plant interactome (fig. S10, fig. S11A). This is not the case for well annotated sub-networks involved in hormone-related or metabolic processes (fig. S11 B and C; 17, 22, 23). Thus, PPIN-1 proteins as a whole, and effector targets in particular, are highly connected nodes within the overall plant network.

The plant response: guarding high value targets

We found that only 2 out of 30 NB-LRR immune receptor fragments in PPIN-1 directly interacted with a pathogen effector (P = 0.04, table S4). In contrast, nearly half of the NB-LRR interactors (24 out of 52), including 7 of the 15 hubs50, were effector targets (P = 4.6 × 10−5 and P = 8 × 10−12, respectively; table S4). N-terminal domains of NB-LRRs can associate with either cellular targets of effector action or with downstream signaling components (10). Thus, our results are consistent with the proposition that NB-LRR proteins can monitor the integrity of cellular proteins and are activated when pathogen effectors act to generate ‘modified self’ molecules (4, 5), for the 30 NB-LRR proteins fragments present in PPIN-1. We note that the interactors of full-length NB-LRR proteins in AI-1MAIN include two of the hub50 proteins that are targeted by both pathogens (TCP14 and CSN5a) (11). Furthermore, in PPIN-1 only 4 of 90 putative RLK receptors interacted directly with a pathogen effector (P = 10−5, table S4), while 46 of 162 interactors of RLKs were effector targets (P = 0.02, table S4). This contrasts with the direct perturbation of PRR-RLK kinase function observed for two Psy type III effectors (2). In sum, our observations are consistent with the view that pathogen effectors are mostly indirectly connected to at least those host immune receptors represented as N-termini fragments in PPIN-1.

Effector targets and immune receptors participate in diverse potential protein modules

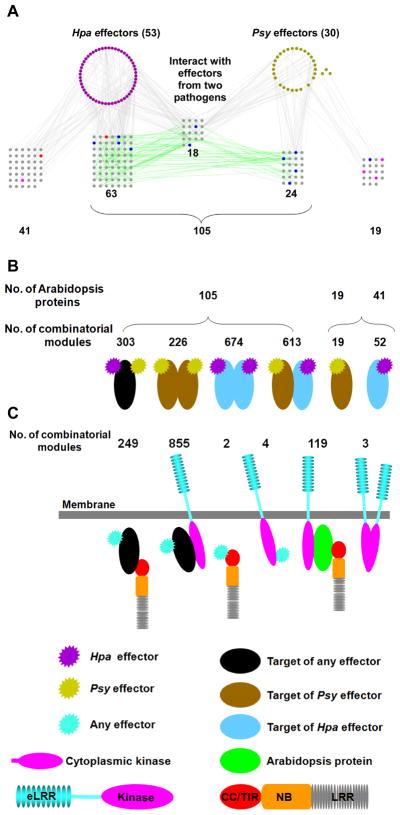

Many effector targets are cellular hubs, and thus likely to be part of various protein modules across different cellular and developmental contexts. We extracted modules of two, three, or four physically connected PPIN-1 proteins (Fig. 3, table S9) and found that the 18 proteins targeted by effectors from both pathogens were involved in 304 combinatorial modules of Psy effector – Arabidopsis protein – Hpa effector (Fig. 3, A and B). Similarly, we noted several hundred combinatorial modules involving 192 interacting Arabidopsis protein pairs where both partners are targeted by effectors from one or both pathogens (Fig. 3A and B, table S9). Ninety-one of the 105 effector targets involved in these modules are present in AI-1MAIN where they have an average degree of 29 (compared to an average degree of 4.8 and 2.6 for PPIN-1 and non-PPIN-1 proteins, respectively, in AI-1MAIN). The targeting of an Arabidopsis protein, or a pair of interacting proteins, by effectors from both pathogens suggests an important function for these cellular machines. We do not infer that these combinations exist in vivo since both pathogens rarely infect the same plant. We also found 19 and 41 proteins interacting with only Psy or Hpa effectors, respectively (Fig. 3, A and B); this apparent pathogen specificity may reflect the limited sensitivity of our experimental pipeline (11) or pathogen life-style-specific interactions. We also assembled a number of combinatorial modules where pathogen effectors indirectly interacted with either an RLK (855) or NB-LRR (249) receptor domain protein via an Arabidopsis protein (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, single Arabidopsis proteins mediated combinatorial modules between a cytoplasmic RLK domain and an NB-LRR N-terminus in 119 cases (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Combinatorial modules in PPIN-1.

(A) The PPIN-1 sub-network of pathogen effector proteins and their Arabidopsis targets. Proteins (nodes) are color coded as in (Fig. 1A, fig. S1). Grey edges: experimental interactions from Fig. 1A. Green edges: added interactions from AI-1 and LCI (fig. S2). From the total of 165 effector targets, 105 interact with at least one other target, while 41 and 19 interact only with Hpa or Psy effectors, respectively. (B) Schematic representation of combinatorial modules involving effectors and effector targets in PPIN-1 (data extracted from A). Number of proteins (top) and number of combinatorial modules (bottom) are indicated for each category. (C) Schematic representation of novel combinatorial modules involving immune receptors. The numbers for each category are listed on top.

Experimental validation of host proteins targeted by multiple pathogen effectors

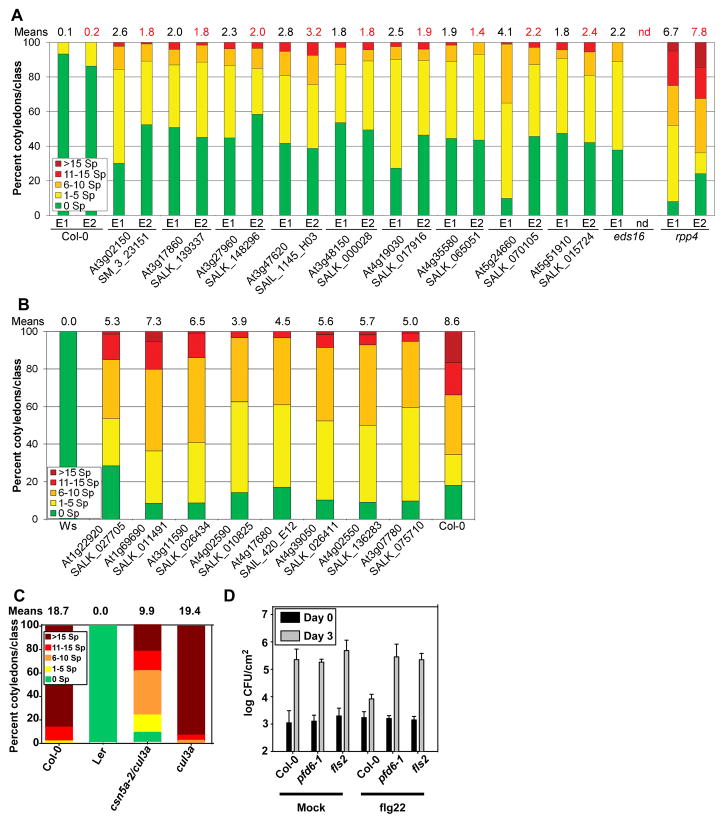

We functionally validated the 18 proteins targeted by effectors from both pathogens (Fig. 1A, Fig. 3A). This subset includes seven of the 15 hubs50 proteins from AI-1MAIN (table S8). We assayed whether these effector targets function to positively regulate host defense (mutation leads to enhanced host susceptibility), negatively regulate host defense (mutation leads to enhanced host resistance) or function to facilitate infection (mutation also leads to enhanced host resistance). We discovered enhanced disease susceptibility to two different Hpa isolates, Emwa1 and Emoy2, for nine of 17 loci for which insertion mutants were available (29, 30) (Fig. 4A, fig. S12A; table S10). Mutants in the eight remaining loci did not exhibit enhanced disease susceptibility. However, at least six of these eight exhibited enhanced disease resistance to the virulent Hpa isolate Noco2 (Fig. 4B, table S10). Moreover, this enhanced disease resistance phenotype was maintained at a later time point in the infection cycle (table S10). Hence, 15 of 17 proteins targeted by effectors from both pathogens, including all seven of the 15 hubs50 proteins, have mutant phenotypes consistent with immune system functions. Preliminary observations also suggest that the mutants for JAZ3 (At3g17860) and LSU2 (At5g24660) expressed an enhanced disease susceptibility phenotype following inoculation with P. syringae DC3000(avrRpt2) (fig. S12B), in addition to the being required for full immune function during Hpa infection (Fig. 4A). This suggests that these genes are required for pathogen growth-suppression mediated by the RPS2 NB-LRR protein

Fig. 4. Functional validation of host proteins interacting with effectors from both pathogens.

(A) Nine host proteins interacting with effectors from both pathogens are required for full immune system function. 12 day old seedlings were inoculated with the avirulent Hpa isolates Emwa1 (E1) or Emoy2 (E2). Infection classes were defined by the number of asexual sporangiophores (Sp) per cotyledon, determined at 5 days post-inoculation (dpi) and displayed as a heat map from green (more resistant) to red (more susceptible); with the mean number of Emwa1 (black) or Emoy2 (red) sporangiophores per cotyledon noted above each bar. Col-0 and rpp4 are resistant and susceptible controls for both Hpa isolates, respectively. The eds16 mutant is a control for compromised MTI (34). See table S10 for means +/− two times standard error, sample size, additional alleles and independent repetitions. (B) At least six host proteins targeted by effectors from both pathogens are required for maximal pathogen colonization. Experiment as in (A), but using spores from the virulent Hpa isolate Noco2 and counting the number of sporangiophores (Sp) per cotyledon at 4 dpi. Ws and Col-0 represent the resistant and susceptible controls, respectively. For means +/− two times standard error, sample size, additional alleles and independent repetitions see table S10. Seven unrelated mutant lines inoculated with Hpa isolate Emwa1 did not exhibit altered disease resistance (means and +/− two times standard error of the means: Col-0 = 1.3 +/− 0.2; seven mutant lines = 0.8–1.8 +/− 0.3; rpp4 = 16.1 +/− 0.7). (C) The csn5a-2 cul3a double mutant exhibits enhanced resistance to Hpa isolate Emco5. Number of asexual sporangiophores (Sp) was counted at 5 dpi for each of the indicated genotypes. Col-0 and Ler were susceptible and resistant controls, respectively. (D) Bacterial growth (colony forming unit – CFU/cm2, expressed on a log scale) following flg22 (right) or mock treatment (water, left) of leaves of the indicated genotypes followed 24 hours later by infection with Pto DC3000. Bacterial growth was assessed at 3 dpi. Error bars: two standard errors of the mean (n = 4).

In yeast, deletion of genes encoding hubs in a binary protein interaction network tend to cause multiple phenotypes (15). We were therefore surprised that at least the seven hubs50 among these 17 proteins did not express pleiotropic morphological mutant phenotypes. CSN5a (At1g22920), a subunit of the COP9 signalosome and a hub50 in AI-1MAIN, did. CSN5a interacts with 29 distinct effectors from Hpa and Psy in our experiment, and is also a demonstrated target of a geminiviral virulence protein (31). It also interacts with N-termini of NB-LRR proteins and cytoplasmic domains of RLKs (table S9). The morphological consequences of csn5a pleiotropy can be suppressed by reducing the expression of either of the two Arabidopsis CUL3 subunits (32). We found that csn5a-2 cul3a seedlings displayed enhanced disease resistance compared to controls following infection with virulent Hpa (Fig. 4C). These results correlated with infection-triggered over-accumulation of PR1 protein, a common marker for MTI, in Hpa (fig. S12C) or Psy infected (fig. S12D) csn5a-2 cul3a plants, compared to Col-0. Hence, our observed enhanced disease resistance phenotype of csn5a is not due to its pleiotropic morphological phenotypes. Many proteins are substrates for CSN5a dependent degradation, perhaps including many of its interactors; thus its elimination or perturbation by effectors could plausibly alter immune function by altering clearance of both host and pathogen proteins.

We also validated prefoldin 6 (PFD6; At1g29990; Fig. 4D, fig. S13), because of its interaction with the known defense regulator EDS1 (Enhanced Disease Susceptibility 1) and two bacterial effectors (table S9, 10). We tested whether pfd6-1 exhibited signs of modified MTI by assaying flagellin (flg22 peptide)-induced disease resistance. Bacterial growth in flg22 pre-treated leaves of Col-0 plants was 10–20 times less than that in mock pre-treated leaves, reflecting successful MTI. This flg22-induced MTI was compromised in pfd6-1 plants (Fig. 4D). Transcriptional induction of molecular MTI markers was abolished in the fls2 mutant, which lacks the PRR receptor for flg22 peptide, and largely impaired in pfd6-1 (fig. S13). These results link PFD6 to MTI downstream of FLS2 PRR receptor function (10, 33). Collectively, these results (Fig. 4) validate the biological significance of PPIN-1, and confirm that pathogen effectors target host proteins required for effective defense or pathogen fitness. To facilitate further hypothesis testing, we present the local networks for the five significantly targeted hubs (Fig. 2D, table S4) and point out connections to cellular functions potentially relevant to immune system function (fig. S14-S18).

Conclusions

Our analyses reveal that oomycete and bacterial effectors separated by ~1 billion years of evolution target an overlapping subset of plant proteins that include well-connected cellular hubs. Our functional validation supports the notion that effectors are likely to converge onto interconnected host machinery to suppress effective host defense and facilitate pathogen fitness. We predict that many of the 165 effector targets we defined will also be targets of additional, independently evolved effectors from other plant pathogens. We anticipate that effectors that target highly connected cellular proteins fine tune cellular networks to increase pathogen fitness and that evolutionary forces integrate appropriate immune responses with those perturbations. As proposed in the Guard Hypothesis, our data are consistent with indirect connections between pathogen effectors and NB-LRR immune receptors, at least for the NB-LRR fragments represented in PPIN-1. The high degree of the effector targets argue against a ‘decoy’ role for these proteins. While the concept of cellular decoys evolved to intercept pathogen effectors is attractive, and likely true in one case in the plant immune system (27), these are expected to have few, if any, additional cellular functions and as such would likely have very few other interaction partners in the protein interaction network. Most of the 673 immune interactors have no previously described immune system function. Our results bridge plant immunology, which predicted that effectors should target common proteins, and network science, which proposes that hubs should be targets for network manipulation (25–28). Derivation of general rules regarding the organization and function of host cellular machinery required for effective defense against microbial infection, and detailed mechanistic understanding of how pathogen effectors manipulate these machines to increase their fitness, will facilitate improvement of plant immune system function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH GM-066025, NSF 2010 0929410 and DOE FG02-95ER20187 to J.L.D.; BBSRC E024815, F005806 and G015066 to J.B.; NSF 0703905 to M.V., J.R.E., D.E.H.; NIH P50-HG004233 to M.V.; and NSF 0520253, 0313578 and 0726408 to J.R.E. D.M. was supported by AGRONOMICS LSHG-CT-2006-037704 from 6th Framework Program of the European Commission to Claire Lurin; We acknowledge the NSF funded ABRC and SIGNAL projects for seeds and clones, respectively. We thank L. Baxter (Warwick Systems Biology, United Kingdom) for Arabidopsis/Papaya ortholog identification, B. Charloteaux (CCSB, Boston, USA) for assisting in some bioinformatics analyses, B. Kemmerling (University of Tuebingen, Germany) for several RLK clones not contained in SIGNAL, and C. Somerville and Y. Gu (UC Berkeley, USA), T. Mengiste (Purdue University, USA) and X.-W. Deng (Yale University, USA) for seeds. The EU Effectoromics Consortium was funded by EU ERAPG and includes: A. Cabral and G. van den Ackerveken (Utrecht University, The Netherlands); J. Bator, R. Yatusevich, S. Katou and J. Parker (Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research, Cologne, Germany); G. Fabro and J. Jones (The Sainsbury Laboratory, Norwich, United Kingdom); M. Coates and T. Payne (University of Warwick, Warwick, United Kingdom). M.V. is a “Chercheur Qualifié Honoraire” from the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS, Wallonia-Brussels Federation, Belgium). Binary interaction data are supplied in table S2 in SOM.

Footnotes

Author contributions:

MSM: initiation of project, lead for experimental design and Y2H analyses, data analyses, and writing the manuscript

A-RC: lead for bioinformatics analyses, database design, and writing the manuscript

MD: lead for Y2H analyses, experimental quality control, data analysis, and writing the manuscript

PE: validation of 18 common pathogen effector targets, data for Fig. 4A, B and table S10, and writing the manuscript

JS: network data analysis

JM: evolutionary analyses of pathogen targets and mRNA expression analyses

MT, BS: support for statistical analyses

MG: quality control of Y2H data

TH: database design and analysis of all IST sequencing traces

MTN: provided experimentally validated type III effector clones

SJP: statistical analysis of connectivity shown in Fig. 2B

SED: participation in Y2H screening of H. arabidopsidis ORFs and making groups of H. arabidopsidis ORFs and network data analysis

LG: Y2H screening of H. arabidopsidis ORFs and verification of interactions

VR, MMP, FG, BJG, ST, DM, MB: Y2H pipeline

CJH: validation of Y2H P. syringae data and assistance with Fig. 4

NM: genotyped all validation mutants for Fig. 4A and B

LG, HC:web-based visualization of PPIN-1

YH: bacterial infection assays for fig. S12B

JV: discussion of Y2H analyses and experimental quality control data

FPR: discussion, oversight of statistical analyses

DEH: oversight of CCSB operations

JRE: discussion, analyses, provision of A. thaliana ORFs

MV: conception and planning of project, discussion and oversight of analyses

JB: planning of project, organization of Hpa candidate effector clones

PB: conception and planning of project, oversight of Y2H and quality control and statistical analyses, and writing the manuscript

JLD: conception and planning of project, oversight of biological validation experiments and analyses, and writing the manuscript

References cited

- 1.Zipfel C. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:414. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boller T, He SY. Science. 2009;324:742. doi: 10.1126/science.1171647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodds PN, Rathjen JP. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:539. doi: 10.1038/nrg2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dangl JL, Jones JD. Nature. 2001;411:826. doi: 10.1038/35081161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones JD, Dangl JL. Nature. 2006;444:323. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lukasik E, Takken FL. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:427. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Ooijen G, et al. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:1383. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang JH, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409660102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baxter L, et al. Science. 2010;330:1549. doi: 10.1126/science.1195203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glossary, materials and methods, supporting figures and supporting tables are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 11.Arabidopsis Interactome Mapping Consortium, (co-submitted).

- 12.Dreze M, et al. Methods Enzymol. 2010;470:281. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)70012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun P, et al. Nat Methods. 2009;6:91. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cusick ME, et al. Nat Methods. 2009;6:39. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu H, et al. Science. 2008;322:104. doi: 10.1126/science.1158684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis JD, Guttman DS, Desveaux D. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:1055. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng ZY, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D975. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan X, et al. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zipfel C, et al. Nature. 2004;428:764. doi: 10.1038/nature02485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sackton TB, et al. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1461. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holub EB. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:516. doi: 10.1038/35080508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang P, et al. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:27. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaillais Y, Chory J. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:642. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0610-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert R, Jeong H, Barabasi AL. Nature. 2000;406:378. doi: 10.1038/35019019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Chassey B, et al. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:230. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyer MD, et al. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calderwood MA, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U SA. 2007;104:7606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uetz P, et al. Science. 2006;311:239. doi: 10.1126/science.1116804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alonso JM, et al. Science. 2003;301:653. doi: 10.1126/science.1086391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sessions A, et al. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2985. doi: 10.1105/tpc.004630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lozano-Duran R, et al. Plant Cell. 2011 tpc.110.080267. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gusmaroli G, Figueroa P, Serino G, Deng XW. Plant Cell. 2007;19:564. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robatzek S, Chinchilla D, Boller T. Genes Dev. 2006;20:537. doi: 10.1101/gad.366506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuda K, Sato M, Glazebrook J, Cohen JD, Katagiri F. Plant Journal. 2008 Sep;55:1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.