Abstract

Successful social interactions rely on the ability to make accurate judgments based on social cues as well as the ability to control the influence of internal or external affective information on those judgments. Prior research suggests that individuals with schizophrenia misinterpret social stimuli and this misinterpretation contributes to impaired social functioning. We tested the hypothesis that for people with schizophrenia social judgments are abnormally influenced by affective information. 23 schizophrenia and 35 healthy control participants rated the trustworthiness of faces following the presentation of neutral, negative (threat-related), or positive affective primes. Results showed that all participants rated faces as less trustworthy following negative affective primes compared to faces that followed neutral or positive primes. Importantly, this effect was significantly more pronounced for schizophrenia participants, suggesting that schizophrenia may be characterised by an exaggerated influence of negative affective information on social judgment. Furthermore, the extent that the negative affective prime influenced trustworthiness judgments was significantly associated with patients’ severity of positive symptoms, particularly feelings of persecution. These findings suggest that for people with schizophrenia negative affective information contributes to an interpretive bias, consistent with paranoid ideation, when judging the trustworthiness of others. This bias may contribute to social impairments in schizophrenia.

Introduction

Successful social interactions rely on the ability to make accurate social judgments of others based on a variety of complex cues indicating a person’s trait and state qualities: Is this person trustworthy, competent, or domineering? Are they feeling angry, disappointed, or bored? These social judgments influence our overall impressions of others and are directly related to our social behavior (Adolphs, 2002; Todorov, 2008). It is well established that schizophrenia patients do not accurately judge social cues, such as facial expressions (Shannon M. Couture, Penn, & Roberts, 2006). Importantly, these deficits in social and affective judgments predict social functioning (Hooker & Park, 2002; Poole, Tobias, & Vinogradov, 2000) and mediate the relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome (Brekke, Kay, Lee, & Green, 2005; Gard, Fisher, Garrett, Genevsky, & Vinogradov, 2009). Identifying the mechanisms that contribute to the misinterpretation of social cues in schizophrenia could facilitate the development of effective interventions and ultimately improve outcome. However, at this point, the factors that influence social interpretations in schizophrenia are unclear.

One possible mechanism is that internal or external affective information is exerting inappropriate influence over social judgments and consequently affecting social functioning. That is, schizophrenia patients may have an impaired ability to control the influence of affective information on social judgments. Affective priming studies with healthy adults demonstrates that judgments, including judgments about a person’s state and trait characteristics, are influenced in a mood-congruent manner by the observer’s affective state and/or by affective information in the environment that may impact affective state (Forgas, 1995; Murphy & Zajonc, 1993; Schwarz & Clore, 1983). This bias occurs even when the internal or external affective information has an incidental cause and is irrelevant to the present judgment, thereby contributing to misinterpretations. For example, people are more likely to judge a face as happy after a positive mood prime, such as viewing a pleasant film, and more likely to judge a face as sad, after a negative mood prime, such as viewing a sad film (Niedenthal, Halberstadt, Margolin, & Innes-Ker, 2000). Disorders that are characterized by the persistent elevation of an affective state show interpretive biases even in the absence of priming (Mathews & MacLeod, 2005); people with major depressive disorder are more likely to identify ambiguous facial expressions as sad and less likely to identify them as happy (Joormann & Gotlib, 2006). Affective priming reveals these biases in formerly depressed patients who report normal mood (LeMoult, Joormann, Sherdell, Wright, & Gotlib, 2009). Importantly, these interpretive biases contribute to the onset and maintenance of illness (Bouhuys, Geerts, & Gordijn, 1999) and are now a target for treatment (MacLeod, Koster, & Fox, 2009).

Despite the vast literature on social and affective perception deficits in schizophrenia (Edwards, Jackson, & Pattison, 2002; Marwick & Hall, 2008), reports of interpretive bias are surprisingly rare. However, schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder in which internal affective state may be variable across different subtypes and stages of illness (Arndt, Andreasen, Flaum, Miller, & Nopoulos, 1995; Herbener & Harrow, 2002). Without direct manipulation of affect, the variation in internal affective state across participants may obscure social judgment biases that exist on an individual level. Furthermore, incidental affective state is most likely to influence judgment when cognitive appraisals of affect are consistent with the nature of the judgment (Dunn & Schweitzer, 2005; Smith & Ellsworth, 1985). Feelings of paranoia are common among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Tandon, Nasrallah, & Keshavan, 2009). Therefore, schizophrenia patients should be most susceptible to interpretive bias when feelings of threat are elevated and the social judgment pertains to interpersonal safety.

Indeed, the studies which have demonstrated information processing biases suggest that social cues are often interpreted in a manner consistent with paranoid feelings and that paranoid patients exhibit this bias more than non-paranoid patients (Green & Phillips, 2004). For example, schizophrenia patients tend to identify a person as looking at them rather than away from them (Hooker & Park, 2005) – a self-referential bias that is more pronounced in paranoid patients as compared to non-paranoid patients (Rosse, Kendrick, Wyatt, Isaac, & Deutsch, 1994). In addition, signal detection analyses of facial affect recognition performance indicates that schizophrenia patients are less likely to interpret facial expressions as happy and more likely to interpret facial expressions as sad or fearful (Tsoi et al., 2008). This bias might be particularly related to paranoid symptoms, as prior studies show that paranoid patients have an enhanced ability to identify fear (Kline, Smith, & Ellis, 1992; Phillips et al., 1999) even though they are also less likely to look at important facial features (Green, Williams, & Davidson, 2003) and to incorporate information about social context (Green, Waldron, & Coltheart, 2007; Green, Waldron, Simpson, & Coltheart, 2008). These apparently conflicting findings would be expected if internal feelings of threat are influencing the social judgment.

Initial evidence from affective priming studies in schizophrenia patients supports this hypothesis (Hoschel & Irle, 2001; Suslow, Roestel, & Arolt, 2003). When positive, negative and neutral facial expression primes were subliminally presented prior to a valence judgment, schizophrenia patients were more likely than control subjects to judge neutral faces and objects as unpleasant after the negative expression prime. There was no difference between groups after the positive prime. This demonstration of affective priming effects on valence judgments provides initial evidence of abnormalities in schizophrenia. However, more targeted investigations of specific factors concerning the affective prime and type of judgment are necessary to fully understand the mechanisms and consequences of interpretive biases in schizophrenia.

Here we investigate interpretive bias by presenting threat-related pictures and measuring the influence of that affective information on a trait judgment pertaining to interpersonal safety, i.e., the trustworthiness of unfamiliar people. Traits, such as trustworthiness, concern a person’s character and are perceived as more stable than emotional states. Therefore, interpretive bias in trustworthiness judgments may have long-lasting impact on decisions to avoid interpersonal relationships.

Since paranoia, including suspiciousness and distrust of others, is a common symptom of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Nayani & David, 1996; Tandon et al., 2009), it is reasonable to predict that schizophrenia patients would judge faces as less trustworthy than healthy controls. However, prior studies that have investigated this hypothesis without affective priming have produced mixed results including evidence that schizophrenia patients judge faces as less trustworthy (Pinkham, Hopfinger, Pelphrey, Piven, & Penn, 2008), more trustworthy (Baas, van't Wout, Aleman, & Kahn, 2008), and no different than control subjects (Couture, Penn, Addington, Woods, & Perkins, 2008). Identifying the influence of incidental affective information on trustworthiness judgments could help explain these conflicting findings.

In the present study, the influence of affective information on social judgment was investigated with the following predictions: 1) relative to healthy control participants, schizophrenia patients will show an exaggerated effect of a threat-related affective prime on social judgment, such that they will rate the same face as less trustworthy after the threat prime as compared to the neutral prime. No difference in the influence of the positive affective prime between groups is expected; 2) the influence of the threat-related affective prime on trustworthiness judgments will be most extreme in patients with paranoid symptoms. Participants completed a task in which they judged the trustworthiness of unfamiliar faces. The presence of affective information was manipulated by showing a negative (threatening), neutral, and positive picture prime just prior to the social judgment. Influence of the threat-related prime on the trustworthiness judgment was measured in two ways: 1) the trustworthiness rating after each prime condition - this provides information about group differences in the presence or absence of threat-related information; 2) the difference between trustworthiness ratings after the threat-related prime and trustworthiness ratings after the neutral prime. This difference score provides a priming effect index because it represents each person’s shift in judgment as a result of the affective prime. Therefore, it accounts for individual response tendencies, such as a tendency to rate faces as more or less trustworthy, in the absence of affective information.

Methods

Participants

23 volunteers with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 35 non-psychiatric, healthy adult volunteers participated in the study. Schizophrenia subjects were recruited from community mental health centres and outpatient clinics in the San Francisco Bay area. Diagnosis was assessed via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) and information from the subject’s caretaker, medical team, and medical record. Symptom severity was assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale-Extended (PANSS-E) (Kay, Opler, & Fiszbein, 1987; Poole et al., 2000). Trained research staff conducted the clinical assessments. Final diagnosis and PANSS-E ratings were reached by consensus between two raters and supervised by a licensed psychiatrist (S.V.). PANSS-E ratings for positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms are reported. IQ was assessed with the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (Wechsler, 1999). Inclusion criteria were: diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, age 18–60 years, and English as a primary language (learned before age 12). Exclusion criteria were: IQ below 70, history of head trauma, neurological or major medical illness, or active substance dependence (DSM-IV criteria) within the past six months.

Healthy adult control subjects were recruited from the same geographic area. Control subjects were screened for schizotypal traits using the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (Raine, 1991) and screened for psychiatric, neurological and general medical problems with self-report questionnaires and a structured clinical interview that assessed past and current Axis I psychological symptoms, use of psychological/psychiatric services, psychiatric and non-psychiatric medication use, academic and learning history, and general medical health including neurological and/or perception problems. IQ was assessed with the WASI. Exclusion criteria were: SPQ score above 30, IQ below 70, current use of psychotropic medication, history of or current psychiatric or neurological disorder (including substance abuse), or head injury with loss of consciousness. Trained research staff conducted the screening. Diagnoses relevant to exclusion were reached by consensus and supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist (C.H.). The study was approved by the ethical review boards at the University of California, Berkeley and University of California, San Francisco. Participants gave written informed consent. Subjects received nominal payment for their participation.

Demographic data for the two groups are summarized in Table 1. Despite efforts to match the two groups on demographic variables, the groups differed in age, education and gender. These variables were entered as covariates in the statistical analyses.

Table 1.

Demographics & Clinical Details

| SZ Subjects | Control Subjects | Differences Between Groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (F/M) | 2F/21M | 13F/22M | χ2 (1) = 13.52, p < .001 |

| Age: mean (SD), [range] | 44.22 (10.3),[23–59] | 49.17 (7.65), [24–62] | t(56) = 2.10, p = .041, d = .56a |

| Education: mean (SD), [range] | 13.35 (2.2), [9–20] | 14.40 (1.40), [12–16] | t(56) = 2.26, p = .028, d = .60 |

| WASI IQ: mean (SD), [range] | 102 (17.4), [73–138] | 111 (10.7), [87–126] | t(40) = 1.97, p = .055, d = .53 |

| Diagnosis: n [%] | |||

| Schizoaffective: | 8 [34.78%] | - | - |

| Schizophrenia: | 15 [65.22%] | - | - |

| SZ Subtypes: | Paranoid 7/15 | - | - |

| Catatonic 1/15 | - | - | |

| Undifferentiated 6/15 | - | - | |

| Residual 1/15 | - | - | |

| - | - | ||

| Age of Onset: mean (SD), [range] | 19.75 (6.2), [5–31] | - | - |

| Length of Illness: mean (SD), [range] | 26.00 (12.4), [5–47] | - | - |

| Antipsychotic Medication: n [%] b | - | - | |

| Typical: | 3 [13.4%] | - | - |

| Atypical: | 18 [78.26%] | - | - |

| PANSS Symptoms : mean (SD), [range] | - | - | |

| Positive Symptoms | 2.44 (1.0), [1 – 4] | - | - |

| Negative Symptoms | 2.23 (.8), [1 – 3.9] | - | - |

| Disorganized Symptoms | 1.74 (.7), [1 – 3.4] | - | - |

Cohen’s d effect size

Medication details were obtained for 23/25 patients

Task and Stimuli

Participants completed a social judgment task [adapted from (Adolphs, Tranel, & Damasio, 1998)] in which they rated the trustworthiness of unfamiliar faces. An affective prime, i.e. an emotionally provocative scene, was presented just prior to the face. Valence ratings of the affective primes were collected, in a separate session, after completion of the social judgment task.

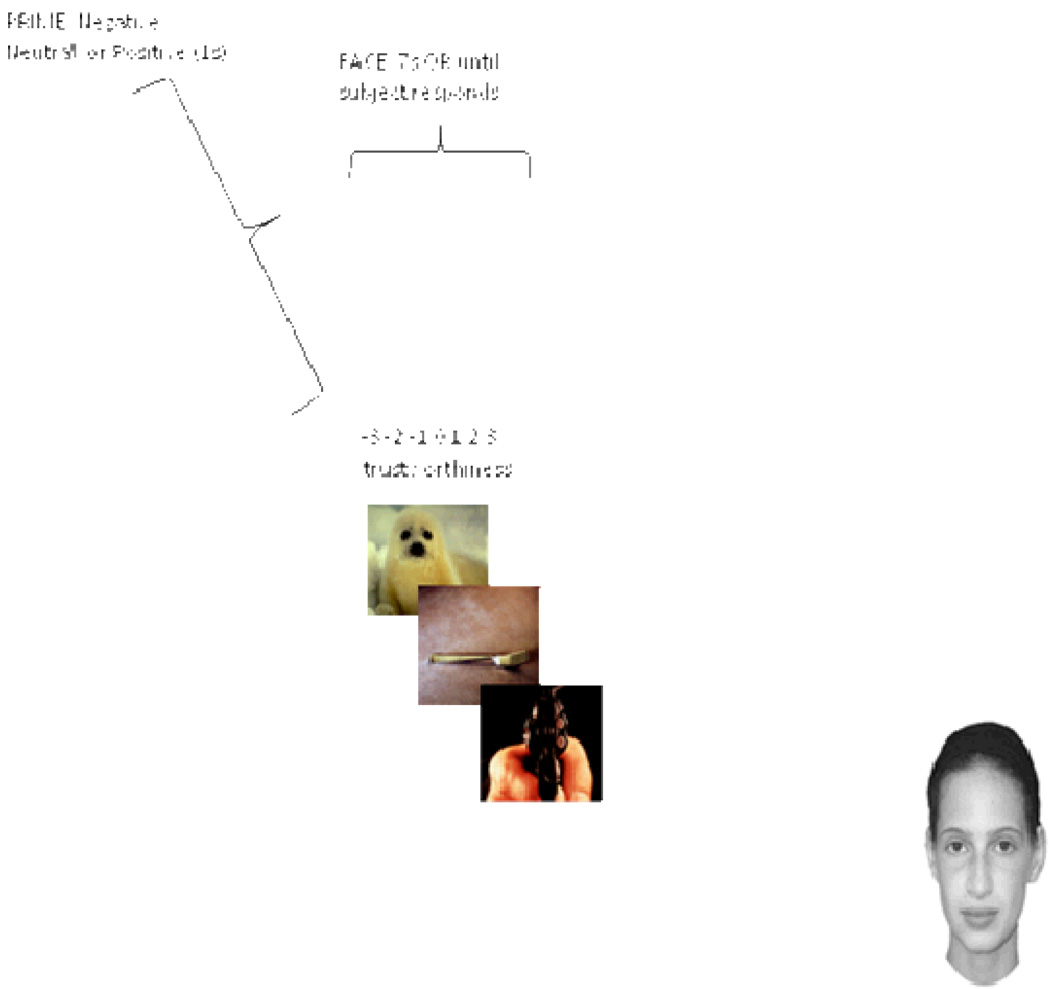

In the social judgment task (See Figure 1), participants were told that they would see a series of scenes followed by faces. They were asked to rate each face on a 7 point scale according to how trustworthy the person appeared (−3 = very untrustworthy, +3 = very trustworthy). It was emphasized that the scenes and the faces were not related, and that the participant’s job was to rate the faces alone. Instructions for how to evaluate trustworthiness were identical to Adolphs et al. (1998). Participants were asked to “imagine trusting the person in a very serious situation, for instance, with all your money or with your life”.

Figure 1.

Social Judgment Task. Subjects were asked to rate the trustworthiness of unfamiliar faces following a negative (threat-related), neutral, and positive prime.

There were two alternate forms of the task. (Two forms were created for later use in a treatment study). Each form of the task contained 49 black and white photographs of unfamiliar male and female faces in natural poses taken from the 100 face stimulus set in Adolphs et al. (1998). Each face was rated for trustworthiness after each of the three prime conditions [negative (threatening), neutral, and positive] for a total of 147 trials. Normed trustworthiness ratings of the faces used in form 1 ranged from −2.45 to 1.57; in form 2 from −2.66 – 1.83 (Adolphs et al., 1998). The faces in each form did not differ in ratings of trustworthiness based on the normative sample [Form 1 M(SD)= −.25, (1.14); Form 2 M(SD) = −.25, (1.17)], t(96) = −.004, p = .997].

Affective primes were taken from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) (Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2005). 49 pictures in each condition were selected. Threat-related negative primes were IAPS pictures that were identified by a group of UC Berkeley undergraduates as the most threatening but least disgusting of the picture set. The selected threat-related primes included pictures of snakes, spiders, weapons, and interpersonal assault. Population means of valence and arousal ratings are published in the IAPS manual; the rating scale is from 1 (unpleasant valence/low arousal) to 9 (pleasant valence/high arousal). Mean valence rating from the IAPS manual of these threat-related primes was 2.89 (SD = .73) and the mean arousal rating was 6.28 (SD = .57). Neutral primes were neutral on valence (M = 4.99, SD = .3) and low on arousal (M = 2.91, SD = .6); typically portraying household objects. Positive primes were positive on valence (M = 7.62, SD = .39) and high on arousal (M = 5.48, SD = .85); typically portraying sports and food. Paired Samples t-tests on the normed ratings confirmed that the negative affective primes were significantly more unpleasant (t(48) = 14.63, p < .001) and arousing (t(48) = 27.38, p <.001) than neutral primes. Positive primes were significantly more pleasant (t(48) = 38.39, p<.001) and arousing (t(48) = 20.25, p<.001) than neutral primes. Positive and negative affective primes differed on valence (t(48) = 36.98, p<.001) and arousal (t(48) = 5.63, p<.001), such that the negative prime pictures were more unpleasant and arousing than the positive primes.

Primes were randomly assigned to faces and the face-prime pairs were presented in a fixed, pseudo-random order; none of the faces appeared twice in a row. Primes were presented for 1 second, followed by the face presented for 7 seconds (or until the subject responded), followed by an inter-trial interval of 1.5 seconds. The subject’s trustworthiness rating was the dependent variable of interest. Subjects completed the task on a Dell Laptop computer and the stimuli were presented with E-Prime software.

Validation of Affective Primes

Participants (21 controls and 19 schizophrenia) returned to the lab on a separate day and rated the pleasantness of the each of the IAPS pictures that were used as affective primes. Pictures were rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from −3 (extremely unpleasant) to +3 (extremely pleasant). The primes were presented in random order, remaining on the screen until participants responded.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted with SPSS. Variables were screened for normalcy and outliers, defined as 2.5 or more standard deviations away from the mean of each group. Outliers were replaced with the group mean accordingly. Two scores were replaced: one negative response in the control group, one positive response in the patient group.

Priming Effect Index: Negative and Positive Difference Scores

Negative difference scores were calculated by subtracting trustworthiness ratings after the neutral prime from trustworthiness ratings after the negative affective prime. Positive difference scores were calculated by subtracting trustworthiness ratings after the neutral prime from trustworthiness ratings after the positive affective prime.

Hypothesis Testing

Group differences in the influence of affective primes (Hypothesis 1), were examined with two ANCOVA models: 1) 2 × 3 ANCOVA of trustworthiness ratings with diagnosis (controls vs. schizophrenia) as the between subjects factor and affective prime (negative, positive, neutral) as the within subjects factor; 2) 2 × 2 ANCOVA of difference scores with diagnosis (controls vs. schizophrenia) as the between subjects factor and difference scores (negative, positive) as the within subjects factor. Age, education, and gender were entered as covariates in both models. Independent and Paired Samples T-tests were used to validate observed effects of the prime. Statistics are reported with two-tailed tests. However, since our hypotheses specify the direction of effect, one-tailed tests were accepted and noted when used.

Pearson bivariate correlations (two-tailed) were used to determine whether positive symptoms, particularly levels of suspiciousness, were significantly associated with the effect of threat-related primes on trustworthiness judgments (Hypothesis 2).

Results

Hypothesis #1: Influence of threat-related primes on trustworthiness judgments will be significantly greater in schizophrenia versus healthy control participants

Mean trustworthiness ratings, difference scores and between group statistics are reported in Table 2. ANCOVA results for trustworthiness ratings after each prime condition showed a significant diagnosis by prime interaction. There was no main effect of education, age, gender or diagnosis. Independent Samples T-tests demonstrate that schizophrenia participants rated the faces as less trustworthy than healthy controls after the negative affective prime. This demonstrates that schizophrenia participants have an interpretive bias after the negative affective prime. However, there was no difference between groups after the neutral prime or positive prime. Importantly, results for the neutral prime show that in the absence of negative affective information there is no difference between groups.

Table 2.

All behavioral results including trustworthiness ratings after each prime condition, difference scores (i.e. index of priming effect) and the pleasantness ratings of the affective primes

| Control | SZ | Difference between groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Trustworthiness Ratings: mean (SD) |

|||

| Negative Prime | 0.41 (0.8) | −0.15 (1.07) | t(56) = 2.30, p = .03, d = .61a |

| Neutral Prime | 0.57 (.72) | 0.39 (.65) | t(56) = 0.94, p = .35, d = .25 |

| Positive Prime | 0.54 (62) | 0.42 (.60) | t(56) = 0.72, p = .48, d = .19 |

| Mixed ANCOVA revealed Affective prime * Diagnosis interaction: F(2, 106) = 4.36, p = .02; η2p = .08 b c | |||

| Difference Scores: mean (SD) | |||

| Negative Difference Score | −0.15 (.32) | −0.54 (1.11) | t(56) = 1.94, p = .057d, d = .52 |

| Positive Difference Score | −0.03 (.37) | 0.03 (.38) | t(56) = .573, p = .569, d = .15 |

| Mixed ANCOVA revealed Difference score * Diagnosis interaction: F(1,53) = 6.00, p = .02; η2p= .10 b | |||

|

Pleasantness of Prime: mean (SD) |

|||

| Negative | −2.37 (.36) | −2.47 (.47) | t(38) = .683, p = .50, d = .22 |

| Neutral | .33 (.40) | .39 (.63) | t(38) = .405, p = .70, d = .13 |

| Positive | 2.00 (.64) | 1.61 (.69) | t(38) = 1.56, p = .13, d = .51 |

| Mixed ANCOVA revealed main effect of prime: F (2,70) = 5.518, p = .006; η2p = .14; no prime *diagnosis interaction: F (2,70) = .904, p = .41; η2p= .03 b | |||

Cohen’s d effect size

Age, education, & gender were included as covariates of no interest. Results showed no main effects of these covariates.

η2p = partial eta squared effect size

p=.029, one-tailed test. Because the hypothesis specified the direction of effect (i.e. SZ would rate as less trustworthy) the one tailed t-test is used here.

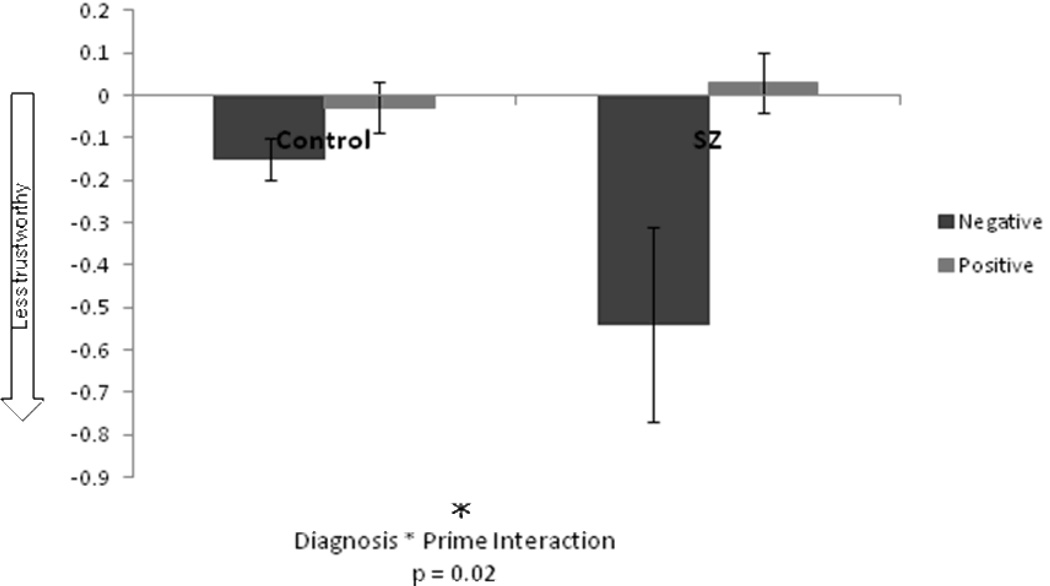

ANCOVA results for the difference scores show a significant prime by diagnosis interaction. There was no main effect of education, gender or diagnosis. Independent Samples T-tests show that schizophrenia patients had a greater shift in judgment after the negative affective prime relative to the neutral prime (p=.029, one-tailed). There was no significant difference between groups in the positive difference score. Although the influence of the positive prime was non-significant for both groups, it influenced judgment in opposite directions which most likely contributed to the prime by diagnosis interaction. This analysis accounts for responses after the neutral prime and demonstrates that the negative affective prime had a greater influence on trust judgments in schizophrenia participants. Although the effect sizes are small, the results are in the predicted direction and consistent across analyses. Results are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Influence of the prime was calculated by subtracting ratings after the neutral prime from ratings after the negative and positive primes, thus zero indicates no priming effect. Schizophrenia patients showed a greater priming effect such that their trustworthiness ratings were significantly lower after the negative prime relative to the neutral compared to control group. There was no group difference between positive priming difference scores.

Validation of Priming Effect

Analyses were conducted to verify that the group difference in priming effect was not due to group differences in effectiveness of the priming paradigm or valence ratings of the affective primes.

1) Was the priming paradigm effective for both groups?

Within each group, Paired Sample T-tests were conducted on the trustworthiness ratings to verify that the priming procedure was effective. Results demonstrate that both groups were significantly influenced by the negative affective prime. Faces were rated as significantly less trustworthy after the negative affective prime as compared to the neutral prime for healthy control (t(34) = 2.85, p = .007, d = .98) as well as schizophrenia participants (t(22) = 2.32, p = .03, d = .98). However, there was no significant difference between trustworthiness ratings after the positive affective prime as compared to the neutral prime for either the healthy control (t(34) = .40, p = .70, d = .14) or schizophrenia participants (t(22) = .41, p = .68, d = .18). The significant influence of the negative affective prime in the healthy control group is consistent with prior research on interpretive biases and suggests that the difference between healthy controls and schizophrenia patients here is not due to task-related confounds (i.e. the task was less effective for healthy controls). The findings also suggest that the positive affective prime did not significantly influence trustworthiness judgments for either group.

2) Did the groups rate the affective primes differently?

Independent Samples T-tests (Table 2) revealed no significant difference between groups in the pleasantness ratings of the negative, neutral, or positive primes. This is consistent with prior data showing that there is no difference between schizophrenia participants and healthy controls in ratings of valence and arousal and response to IAPS pictures (Herbener, 2008; Herbener, Song, Khine, & Sweeney, 2008; Kring, Barrett, & Gard, 2003; Kring & Moran, 2008). Thus, differences in trustworthiness ratings shown here can be attributed to differences in the influence of the primes on subsequent judgments of trustworthiness, not to differences in affective ratings.

Hypothesis #2: Influence of the threat-related primes will be more extreme in schizophrenia participants with high levels of paranoia

Zero-order correlations between symptoms, trustworthiness ratings, and difference scores are shown in Table 3. Correlations with the trustworthiness ratings show that ratings after the negative affective prime were significantly related to symptoms of suspiciousness/persecution. As predicted, schizophrenia participants with a higher level of suspiciousness/persecution were more likely to rate faces as less trustworthy after the negative affective prime. The relationship between trustworthiness ratings after the negative affective prime and the positive symptom cluster was in the predicted direction but did not reach significance. There was no relationship between trustworthiness ratings after the neutral and positive primes and any positive symptoms. Interestingly, there was a significant positive correlation between ratings after neutral and positive primes and the disorganized symptom cluster. Specifically, greater conceptual disorganization and incoherent speech was associated with higher trustworthy ratings after the neutral prime and greater incoherent speech was associated with higher trustworthiness ratings after the positive prime.

Table 3.

| Table 3a: Pearson correlations of symptom clusters with difference scores and raw trustworthiness ratings | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom Clusters | |||

| Positive Symptoms | Negative Symptoms | Disorganized Symptoms |

|

| Negative Difference Score | −0.51* | 0.18 | −0.17 |

| Positive Difference Score | −0.11 | 0.11 | −0.15 |

| Raw Trustworthiness Ratings: | |||

| Negative Prime | −0.30 | 0.20 | 0.11 |

| Neutral Prime | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.48* |

| Positive Prime | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.43* |

| Table 3b: Pearson correlations of symptom components of positive, negative, and disorganized symptom clusters with difference scores and raw trustworthiness ratings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference Scores | Trustworthiness Ratings | ||||

| Negative Difference Score |

Positive Difference Score |

Negative Prime | Neutral Prime | Positive Prime | |

| Positive Symptom Components | |||||

| unusual thought content | −0.46* | −0.26 | −0.24 | 0.39 | 0.26 |

| delusions | −0.50* | −0.14 | −0.29 | 0.38 | 0.33 |

| grandiosity | −0.16 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| suspiciousness | −0.56* | −0.19 | −0.43* | 0.26 | 0.16 |

| hallucinatory behavior | −0.25 | 0.15 | −0.08 | 0.22 | 0.34 |

| Negative Symptom Components | |||||

| emotional withdrawal | 0.11 | 0.23 | −0.01 | −0.20 | −0.08 |

| social withdrawal | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.16 | −0.02 | 0.16 |

| lack of spontaneity | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| poor rapport | 0.24 | −0.05 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| blunted affect | 0.13 | −0.13 | 0.06 | −0.12 | −0.21 |

| motor retardation | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| disturbance of volition | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.32 |

|

Disorganized Symptom Components |

|||||

| conceptual disorganization | −0.29 | −0.35 | 0.01 | 0.51* | 0.34 |

| incoherent speech | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.27 | 0.47* | 0.45* |

| poverty of speech content | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.39 |

| inappropriate affect | −0.26 | −0.31 | −0.02 | 0.41 | 0.25 |

| bizarre appearance | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.11 | −0.04 | 0.14 |

| bizarre social behavior | −0.25 | 0.31 | −0.10 | 0.39 | 0.58* |

p < .05

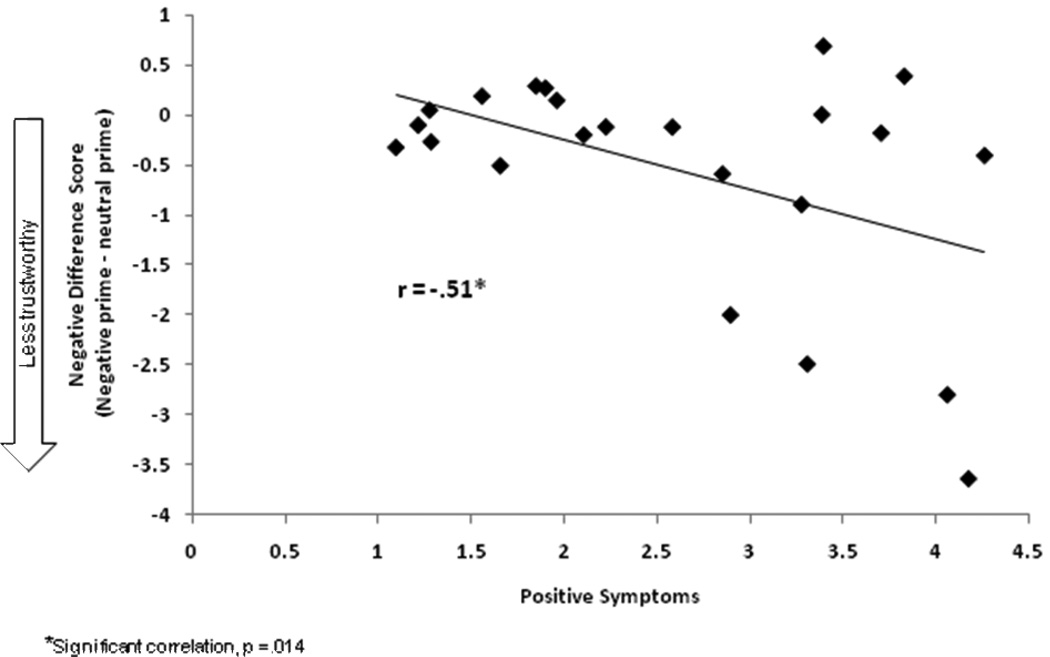

Analysis of the difference scores shows a significant relationship between the positive symptom cluster and negative affective prime difference scores (see table 3 and figure 3). Three of the five component symptoms of the positive symptom cluster were significantly correlated with negative difference scores: unusual thought content, delusions, and suspiciousness/persecution (table 3b). Suspiciousness/persecution showed the largest correlation suggesting that the extent to which negative affect influences trustworthiness judgments varies according to feelings of suspiciousness/persecution.

Figure 3.

The extent to which the negative prime influenced schizophrenia patients’ trustworthiness ratings was significantly related to positive symptoms. The greater severity of positive symptoms, the less trustworthy patients rated faces following the negative prime relative to the neutral prime.

The negative difference score analysis demonstrates that a higher level of positive symptoms is associated with a greater shift in judgment as a result of the negative affective prime relative to the neutral prime. There was no significant correlation between the negative difference score and negative or disorganized symptoms; there was no significant relationship between the positive difference score and any symptoms.

Discussion

This study examined whether affective information had an exaggerated influence on social judgment in schizophrenia. Negative (threat-related), neutral, and positive affective primes were presented just prior to judging the trustworthiness of an unfamiliar face. Two main findings emerged from our study. First, relative to healthy control subjects, schizophrenia patients’ judgments of trustworthiness were more influenced by negative affective primes, such that they judged the person as less trustworthy after the negative affective prime. Second, the extent of this influence was associated with positive symptoms, particularly feelings of suspiciousness and persecution; the greater the severity of positive symptoms, the greater the influence of the negative affective primes on trustworthiness evaluations.

These findings demonstrate an interpretive bias, consistent with paranoia, for evaluations of trustworthiness in schizophrenia. This interpretive bias was only apparent after the presentation of negative affective primes. There was no difference between schizophrenia patients and healthy control participants in their ratings of trustworthiness after the neutral prime and there was also no relationship between positive symptoms and trustworthiness ratings after the neutral prime. The influence of the negative affective prime was not due to schizophrenia participants perceiving the threat-related pictures as more unpleasant than the healthy control group, nor can the effect be explained by an excess of general affective priming in the schizophrenia sample as there was no difference between the groups in the influence of positive affective primes. This pattern of results indicates that schizophrenia participants, especially those with positive symptoms, are particularly sensitive to the influence of incidental threat-related negative affective information on judgments of trustworthiness.

These findings may help explain inconsistencies in prior studies that investigated trustworthiness judgments without affective priming. Some studies report no difference in trustworthiness ratings between healthy control and schizophrenia participants (Baas, Aleman et al., 2008; Couture et al., 2008), yet others demonstrate that schizophrenia participants (Baas, van't Wout et al., 2008) and those at risk for schizophrenia (Couture et al., 2008) judge faces as more trustworthy than healthy controls. However, studies that consider symptom profile indicate that schizophrenia participants with paranoid symptoms judge faces as less trustworthy than both non-paranoid (Pinkham et al., 2008) and healthy control participants (Couture et al., 2009).

Collectively, these studies suggest that schizophrenia patients’ trustworthiness judgments may not be stable, but rather that these social judgments are influenced by factors such as symptom profile and severity, internal affective state, and/or incidental emotional provocations that may impact affective state. Our study specifically investigated these factors. Similar to prior research, we found that across a group of patients with varying levels of symptoms, judgments of trustworthiness did not differ between schizophrenia patients and controls when the prime was affectively neutral. Thus, without specifically manipulating negative affect or the presence of negative affective information through priming, interpretive bias in trustworthiness judgments was not apparent. Our finding that patients with a high degree of paranoid symptoms were most influenced by the negative affective prime suggests that threatening contexts may influence social judgments more in paranoid patients as compared to patients without paranoid symptoms. Interestingly, the participants in Pinkham et al. (2008) made their judgments while undergoing fMRI scanning, a context that most people consider mildly anxiety-provoking and aversive. It is possible that the negative context of the scanner environment may have led paranoid patients to judge faces as untrustworthy in that study. Furthermore, our findings suggest that, in the absence of negative affective priming, disorganized symptoms are associated with judging faces as more trustworthy. Although prior studies which showed schizophrenia spectrum participants as judging faces as more trustworthy (Baas, van't Wout et al., 2008) did not report symptom severity, participants in these studies may have had a high level of disorganized symptoms.

While the current results demonstrate that incidental threat-related information has an exaggerated influence on trust judgments for schizophrenia patients, more research is needed to identify the underlying cause of this effect. Research with healthy adults shows that multiple factors contribute to the influence of affect on trustworthiness judgments, including the specific emotion that is primed, salience of the priming source, the type of judgment, and characteristics of both the target and the observer (Dunn & Schweitzer, 2005; Todorov, 2008). Certain aspects of schizophrenia illness may interact with these factors to cause an exaggerated influence of affect on trust judgments. Our findings here suggest an interaction between primed emotion and psychotic symptoms on trust judgments of unfamiliar faces. We identify two possible mechanisms that are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive and are proposed here to stimulate further research. One possibility, consistent with information processing and cognitive psychology theories, is that the threat-related primes activated paranoid cognitive schemas which then influenced trust assessments. Another possibility, consistent with neurocognitive models in schizophrenia, is that deficits in cognitive control skills contributed to the inability to regulate the influence of threat-related information or feelings on judgment.

First, although we did not assess specific emotional state after the prime, it is likely that the threat-related primes provoked feelings of fear, even if those feelings were relatively mild. Fear is associated with specific action tendencies (i.e. to avoid or escape danger) and cognitive appraisals, including appraisals that escape is uncertain and outside of one’s personal control (Smith & Ellsworth, 1985). Trusting someone “with your money or your life” (as we asked our subjects to imagine doing) involves relinquishing personal control to another person and leaving oneself vulnerable to potential exploitation. Taking such a risk requires certainty about the intentions of the other person and the situational demands that may influence them. Given the type of judgment, emotions that are associated with appraisals of uncertainty and low personal control, such as fear, will have the most influence on trustworthiness judgments. When people feel fearful they overestimate potential dangers, are less likely to take risks, and more likely to avoid uncertain situations (Lerner & Keltner, 2001). These effects of fear have been demonstrated for decisions of financial and physical risks (Au, Chan, Wang, & Vertinsky, 2003; Chou, Lee, & Ho, 2007; Lerner, Gonzalez, Small, & Fischhoff, 2003) and shown here for decisions concerning interpersonal risk – i.e. whether or not to trust someone. Furthermore, appraisals associated with fear may activate core belief systems (schemas) related to psychosis, such as the belief that other people, particularly unfamiliar people, may have malevolent intentions (Beck & Rector, 2005). Our data suggests that paranoid ideation may not influence trust evaluations unless activated by threat-related information. Prior research shows that identifying the source of emotional provocations diminishes the influence of that affective state on unrelated judgments (Dunn & Schweitzer, 2005; Schwarz & Clore, 1983). Therefore, interventions which help patients identify environmental cues or experiences that provoke negative affect might improve both paranoid symptoms and interpretive biases related to those symptoms.

In addition, deficits in cognitive control skills, such as attentional control, which are characteristic of schizophrenia, may contribute to the exaggerated influence of affective state on trust judgments. The influence of emotionally provocative stimuli on affective state and subsequent behaviour can be regulated by cognitive strategies such as evaluation, inhibition, and attentional control (Derryberry & Reed, 2002; Hooker, Gyurak, Verosky, Miyakawa, & Ayduk, 2009; Lieberman et al., 2007). Schizophrenia patients consistently demonstrate behavioural impairments in these skills (Henry et al., 2007; Reichenberg & Harvey, 2007). Our results are consistent with the idea that positive symptoms may interact with cognitive control deficits, resulting in difficulties regulating the influence of negative affect on trustworthiness judgments. Although the current data cannot address this hypothesis directly, future research could investigate whether cognitive control skills predict the extent to which negative affect influences judgment. Evidence of this association would suggest that improving cognitive control skills might help patients control the influence of affect on judgment.

The current study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, although we interpret the results as suggesting that the threat-related primes provoked feelings of fear which then influenced trust judgments, we did not assess emotional state after the primes. Therefore, alternative explanations should be considered and tested. For example, threat-related primes could activate the cognitive category of fear rather than the emotional response and/or the threat-related primes could have provoked emotional responses other than fear. Second, the positive affective primes did not influence trust judgments for either group, suggesting that these primes may not have been effective. The positive primes were not as arousing as the negative primes, indicating that arousal level may contribute to the influence of affect on judgment. Content of the positive primes was also more diverse than the negative primes and therefore the influence may have been more diffuse. Future research should manipulate and assess specific positive and negative emotional states, such as gratitude and anger, which might have different effects on trust judgments (Dunn & Schweitzer, 2005). Finally, although differences in age, education and gender were statistically controlled for in our analyses, future studies should replicate the current results with appropriately matched samples.

In summary, the current study demonstrates that schizophrenia is associated with an interpretive bias, consistent with feelings of paranoia, when judging the trustworthiness of others. These findings have implications for how schizophrenia patients interact with others: an impaired ability to make accurate social judgements due to the inappropriate influence of negative affective information could be an important contributing factor to the chronic and debilitating social behaviour deficits seen in the disorder. Additional research may facilitate the development of interventions whereby patients learn to develop skills and strategies to aid in the regulation of affective information during social judgements and thus minimize misinterpretations.

Acknowledgments

NARSAD Young Investigator Award (C.I.H) and NIMH grants MH71746 (C.I.H.) and MH68725-02 (S.V.) supported this work. Thanks to Asako Miyakawa and Ori Elis for help with data collection and Mark D’Esposito and Robert T. Knight for support with the project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/abn.

References

- Adolphs R. Recognizing emotion from facial expressions: psychological and neurological mechanisms. Behavioral and cognitive neuroscience reviews. 2002;1(1):21–62. doi: 10.1177/1534582302001001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio AR. The human amygdala in social judgment. Nature. 1998;393(6684):470–474. doi: 10.1038/30982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt S, Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Miller D, Nopoulos P. A longitudinal study of symptom dimensions in schizophrenia. Prediction and patterns of change. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(5):352–360. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950170026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au K, Chan F, Wang D, Vertinsky I. Mood in foreign exchange trading: cognitive processes and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Making Process. 2003;91:322–338. [Google Scholar]

- Baas D, Aleman A, Vink M, Ramsey NF, de Haan EH, Kahn RS. Evidence of altered cortical and amygdala activation during social decision-making in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2008;40(2):719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas D, van't Wout M, Aleman A, Kahn RS. Social judgement in clinically stable patients with schizophrenia and healthy relatives: behavioural evidence of social brain dysfunction. Psychol Med. 2008;38(5):747–754. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rector NA. Cognitive approaches to schizophrenia: theory and therapy. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:577–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhuys AL, Geerts E, Gordijn MC. Depressed patients' perceptions of facial emotions in depressed and remitted states are associated with relapse: a longitudinal study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(10):595–602. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199910000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke J, Kay DD, Lee KS, Green MF. Biosocial pathways to functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(2–3):213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou KL, Lee TMC, Ho AHY. Does mood state change risk-taking tendency in older adults? Psychology of Aging. 2007;22:310–318. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture SM, Penn DL, Addington J, Woods SW, Perkins DO. Assessment of social judgments and complex mental states in the early phases of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2008;100(1–3):237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.12.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture SM, Penn DL, Losh M, Adolphs R, Hurley R, Piven J. Comparison of social cognitive functioning in schizophrenia and high functioning autism: more convergence than divergence. Psychol Med. 2009;40(4):569–579. doi: 10.1017/S003329170999078X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL. The Functional Significance of Social Cognition in Schizophrenia: A Review. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2006;32 suppl_1:S44–S63. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Reed MA. Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(2):225–236. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JR, Schweitzer ME. Feeling and believing: the influence of emotion on trust. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88(5):736–748. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Jackson HJ, Pattison PE. Emotion recognition via facial expression and affective prosody in schizophrenia: a methodological review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22(6):789–832. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas JP. Mood and judgment: the affect infusion model (AIM) Psychol Bull. 1995;117(1):39–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Fisher M, Garrett C, Genevsky A, Vinogradov S. Motivation and its relationship to neurocognition, social cognition, and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;115(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Phillips ML. Social threat perception and the evolution of paranoia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28(3):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Waldron JH, Coltheart M. Emotional context processing is impaired in schizophrenia. Cognit Neuropsychiatry. 2007;12(3):259–280. doi: 10.1080/13546800601051847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Waldron JH, Simpson I, Coltheart M. Visual processing of social context during mental state perception in schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33(1):34–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Williams LM, Davidson D. Visual scanpaths to threat-related faces in deluded schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2003;119(3):271–285. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Green MJ, de Lucia A, Restuccia C, McDonald S, O'Donnell M. Emotion dysregulation in schizophrenia: reduced amplification of emotional expression is associated with emotional blunting. Schizophr Res. 2007;95(1–3):197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbener ES. Emotional memory in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(5):875–887. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbener ES, Harrow M. The course of anhedonia during 10 years of schizophrenic illness. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(2):237–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbener ES, Song W, Khine TT, Sweeney JA. What aspects of emotional functioning are impaired in schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 2008;98(1–3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker C, Park S. Emotion processing and its relationship to social functioning in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res. 2002;112(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker C, Park S. You must be looking at me: the nature of gaze perception in schizophrenia patients. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2005;10(5):327–345. doi: 10.1080/13546800444000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker CI, Gyurak A, Verosky SC, Miyakawa A, Ayduk O. Neural Activity to a Partner's Facial Expression Predicts Self-Regulation After Conflict. Biol Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoschel K, Irle E. Emotional priming of facial affect identification in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27(2):317–327. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Gotlib IH. Is this happiness I see? Biases in the identification of emotional facial expressions in depression and social phobia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(4):705–714. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A. The positive and negative syndrome rating scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;45:20–31. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline JS, Smith JE, Ellis HC. Paranoid and nonparanoid schizophrenic processing of facially displayed affect. J Psychiatr Res. 1992;26(3):169–182. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(92)90021-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Barrett LF, Gard DE. On the broad applicability of the affective circumplex: representations of affective knowledge among schizophrenia patients. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(3):207–214. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.02433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Moran EK. Emotional response deficits in schizophrenia: insights from affective science. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(5):819–834. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Technical Report A-6 (Report) Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; 2005. International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. [Google Scholar]

- LeMoult J, Joormann J, Sherdell L, Wright Y, Gotlib IH. Identification of emotional facial expressions following recovery from depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(4):828–833. doi: 10.1037/a0016944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JS, Gonzalez RM, Small DA, Fischhoff B. Effects of fear and anger on perceived risks of terrorism: a national field experiment. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(2):144–150. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JS, Keltner D. Fear, anger, and risk. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(1):146–159. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI, Crockett MJ, Tom SM, Pfeifer JH, Way BM. Putting feelings into words: affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(5):421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Koster EH, Fox E. Whither cognitive bias modification research? Commentary on the special section articles. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(1):89–99. doi: 10.1037/a0014878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwick K, Hall J. Social cognition in schizophrenia: a review of face processing. Br Med Bull. 2008;88(1):43–58. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldn035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A, MacLeod C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:167–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ST, Zajonc RB. Affect, cognition, and awareness: affective priming with optimal and suboptimal stimulus exposures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64(5):723–739. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayani TH, David AS. The auditory hallucination: a phenomenological survey. Psychol Med. 1996;26(1):177–189. doi: 10.1017/s003329170003381x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedenthal PM, Halberstadt JB, Margolin J, Innes-Ker ÃsH. Emotional state and the detection of change in facial expression of emotion. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;30(2):211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Williams L, Senior C, Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Andrew C, et al. A differential neural response to threatening and non-threatening negative facial expressions in paranoid and non-paranoid schizophrenics. Psychiatry Res. 1999;92(1):11–31. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(99)00031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Hopfinger JB, Pelphrey KA, Piven J, Penn DL. Neural bases for impaired social cognition in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. 2008;99(1–3):164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole JH, Tobias FC, Vinogradov S. The functional relevance of affect recognition errors in schizophrenia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2000;6(6):649–658. doi: 10.1017/s135561770066602x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. The SPQ: a scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(4):555–564. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenberg A, Harvey PD. Neuropsychological impairments in schizophrenia: Integration of performance-based and brain imaging findings. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(5):833–858. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosse RB, Kendrick K, Wyatt RJ, Isaac A, Deutsch SI. Gaze Discrimination in patients with schizophrenia: Preliminary Report. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:919–921. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.6.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Clore GL. Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45:513–523. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Ellsworth PC. Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48(4):813–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suslow T, Roestel C, Arolt V. Affective priming in schizophrenia with and without affective negative symptoms. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253(6):292–300. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R, Nasrallah HA, Keshavan MS. Schizophrenia, "just the facts" 4. Clinical features and conceptualization. Schizophr Res. 2009;110(1–3):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov A. Evaluating faces on trustworthiness: an extension of systems for recognition of emotions signaling approach/avoidance behaviors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:208–224. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoi DT, Lee KH, Khokhar WA, Mir NU, Swalli JS, Gee KA, et al. Is facial emotion recognition impairment in schizophrenia identical for different emotions? A signal detection analysis. Schizophr Res. 2008;99(1–3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]