Abstract

Allostatic load theory hypothesizes that stress and the body’s responses to stressors contribute to longer term physiological changes in multiple systems over time (allostasis), and that shifts in how these systems function have implications for adjustment and health. We investigated these hypotheses with longitudinal data from two independent samples (n = 413; 219 girls, 194 boys) with repeated measures at ages 8, 9, 10, and 11. Initial parental marital conflict and its change over time indexed children’s exposure to an important familial stressor, which was examined in interaction with children’s respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) reactivity to laboratory tasks (stress response) to predict children’s basal levels of RSA over time. We also investigated children’s sex as an additional possible moderator. Our second research question focused on examining whether initial levels and changes in resting RSA over time predicted children’s externalizing behavior. Boys with a strong RSA suppression response to a frustrating laboratory task who experienced higher initial marital conflict or increasing marital conflict over time showed decreases in their resting RSA over time. In addition, boys’ initial resting RSA (but not changes in resting RSA over time) was negatively related to change over time in externalizing symptoms. Findings for girls were more mixed. Results are discussed in the context of developmental psychobiology, allostatic load, and implications for the development of psychopathology.

How the body copes with and responds to environmental stress and threat has long been a topic of interest to researchers (Cannon, 1929). Investigating interactions between environmental factors and stress responses over time can contribute to our understanding of long-term changes in physiological functioning and subsequent pathology. The allostatic load framework is a leading pertinent theory, which applies the concepts of allostasis (Sterling & Eyer, 1988) and allostatic load to examine the correlates and sequelae of exposure to environmental stressors (McEwen & Stellar, 1993). The concept of homeostasis refers to the body’s maintenance of internally set levels of function in multiple systems. Allostasis, although seemingly similar, is distinguished by its focus on developmental change and how the body’s internally set levels of function may shift in response to environmental challenge. Environmental stressors and the body’s responses to these stressors contribute to allostatic load, such that dynamic stress response systems and their repeated activation in response to challenges may be moderators or causal agents in allostasis. As moderators of effects, the relation between stress and shifts in physiological system function over time likely depends on individual differences in stress reactivity. As pathways or mediators of effects, stress exposure may shape physiological responses to stressors, which may serve as mechanisms of effects in allostasis such that physiological stress responses cause changes in later physiological function at rest. Such allostatic shifts in internal multisystem functions over time may have profound implications for an organism’s physical and mental health, including problems associated with a state known as allostatic overload (McEwen & Wingfield, 2003). Understanding these dynamic processes is likely to shed light on how to identify individuals most likely to experience allostatic overload as a consequence of Stress Exposure × Stress Response interactions (Lupien et al., 2006).

The majority of pertinent studies have evaluated the allostatic load hypothesis in relation to hypothalamic–pituitary– adrenal axis or sympathetic nervous system activity (see Juster, McEwen, & Lupien, 2010; Miller, Chen, & Zhou, 2007). In addition, many studies have linked concurrent or prior environmental risk factors to poorer allostatic states and allostatic overload (e.g., Fisher, Stoolmiller, Gunnar, & Burraston, 2007; Kertes, Gunnar, Madsen, & Long, 2008; see also Juster et al., 2010), but additional longitudinal research is needed to clarify and more fully test the dynamic nature of the hypotheses in the theory. For example, there is a notable lack of longitudinal research evaluating the processes by which environmental stress may result in changes in physiological functioning over time (e.g., Environmental Stress Exposure × Physiological Stress Response interactions) and how shifts in physiological functioning may manifest as allostatic overload (e.g., maladaptive behavior).

In the current study, we expand the testing of the allostatic load framework in important ways by investigating an index of physiological functioning that has less often been considered in this context, namely, parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity over time as measured by respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). We considered RSA as one potential index of allostatic load in the context of a dynamic stressor, exposure to parental marital conflict, and changes in that conflict over time. In addition, we considered children’s initial RSA stress reactivity (RSA-R) and sex as moderating characteristics in the relations between marital conflict and resting levels of RSA. Finally, we evaluated whether allostatic load (in this instance resting RSA and its change over time) predicted or interacted with sex to predict children’s behavioral functioning (symptoms of allostatic overload) as indexed by externalizing behavior and changes in externalizing behavior over time.

Destructive and antagonistic marital conflict includes acts and threats of physical violence as well as psychological aggression (e.g., insults, intimidation) from either spouse. Destructive marital conflict has been extensively documented as a predictor of maladjustment in children (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003). Consequently, research in this area has turned to understanding the who and the why, including examinations of individual differences that characterize children who are protected from or are especially vulnerable to marital conflict, and the processes that may explain the relations between destructive marital conflict and child maladjustment (Cummings, El-Sheikh, Kouros, & Buckhalt, 2009). Considerable light has been shed on the who, identifying those children who seem to be protected from or vulnerable to the effects of marital conflict. A great deal of this research has focused on physiological systems (e.g., hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal, autonomic nervous system) related to self-regulation, environmental engagement, and fight or flight responding and how functioning in these systems moderates relations between marital conflict and child adjustment. Most relevant to the current report, RSA at rest and in responding to stress have been found to be important moderators in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies on this topic; higher resting RSA or increased RSA suppression in response to stress have been found to function consistently as protective factors in the context of marital conflict (El-Sheikh, Harger, & Whitson, 2001; El-Sheikh & Whitson, 2006; Katz & Gottman, 1995, 1997). More recent longitudinal data have helped to corroborate findings that children in homes characterized by higher levels of marital conflict are especially at risk for developing externalizing problems when they also display lower resting RSA and weaker RSA suppression to stress (El-Sheikh, Hinnant, & Erath, 2011).

Given these robust and consistent moderated relations, it is clear that understanding changes in RSA over time, and factors contributing to this change, is an important endeavor. RSA is a physiological index of PNS influence on the heart via the vagal nerve (cranial nerve X; Berntson, Cacioppo, & Quigley, 1993; Grossman & Taylor, 2007; Porges, 2007). PNS influence facilitates “rest and digest” functions in multiple organs and systems within the body and modulated, incremental increases in physiological functioning to deal with environmental challenge. Vagally mediated reductions in RSA (i.e., RSA suppression), for example, facilitates increases in cardiac output. PNS function and RSA are also linked to the experience (Christie & Friedman, 2004; Kreibig, 2010; Oveis et al., 2009; Stephens, Christie, & Friedman, 2010), expression (Cole, Zahn-Waxler, Fox, Usher, & Welsh, 1996; Marsh, Beauchaine, & Williams, 2008), and regulation of emotion and behavior (Calkins, Dedmon, Gill, Lomax, & Johnson, 2002; Gentzler, Santucci, Kovacs, & Fox, 2009; Gottman & Katz, 2002) via reciprocal connections to components of the central nervous system (Berthoud & Neuhuber, 2000; Porges, 2007; Saper, 2002; Smith & DeVito, 1984). RSA increases through infancy and childhood (Alkon et al., 2006; Bar-Haim, Marshall, & Fox, 2000; Bornstein & Suess, 2000; Calkins & Keane, 2004) and its growth may level off in late childhood or early adolescence (El-Sheikh, 2005; Hinnant, Elmore-Staton, & El-Sheikh, 2011; Salomon, 2005). In addition, RSA has shown stability in infancy and beyond, whereas RSA reactivity seems to stabilize later in childhood (Alkon et al., 2006; Bar-Haim et al., 2000; Calkins & Keane, 2004).

There is a heritable component to RSA and RSA reactivity in response to stress (Boomsma, Van Baal, & Orlebeke, 1990; De Geus, Kupper, Boomsma, & Sneider, 2007; Kupper et al., 2005); however, there is also considerable evidence that RSA and RSA reactivity are susceptible to environmental influence. Infants exposed to angry emotions exhibit greater RSA suppression during the still-face paradigm, a physiological response that is indicative of active coping with stress (Moore, 2009). Repeated exposure to negative emotion and conflict and repeated activation of physiological stress responses may incur systemic “wear and tear” on the PNS, resulting in lower resting RSA and blunted RSA stress responses (for reviews, see Moore, 2010; Porter, Wouden-Miller, Silva, & Porter, 2003; see also Propper & Moore, 2006; Whitson & El-Sheikh, 2003). Similarly, blunted RSA stress responses have been reported for children (Calkins, Graziano, Berdan, Keane, & Degnan, 2008; Hastings & De, 2008) and adolescents (Willemen, Schuengel, & Koot, 2009) who have poorer parent–child relationships. Some research, however, has found that higher levels of marital conflict are associated with higher levels of resting RSA (Davies, Sturge-Apple, Cicchetti, Manning, & Zale, 2009) or a stronger RSA stress response (i.e., suppression; Salomon, Matthews, & Allen, 2000). Also consistent with allostatic load theory, and the only study to test the relations to our knowledge, Salomon (2005) found that greater RSA suppression in children and adolescents predicted lower resting RSA 3 years later.

Lower RSA at rest (Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, & Mead, 2007) and weaker RSA suppression in response to stress (Calkins, Blandon, Williford, & Keane, 2007; Calkins, Graziano, & Keane, 2007; Calkins & Keane, 2004) have been linked to higher levels of externalizing problems with additional evidence suggesting that this relation may be especially strong for children with both lower RSA and weaker RSA suppression (Hinnant & El-Sheikh, 2009). Although few studies have tested sex differences in the relations between environmental characteristics and RSA, there is some evidence that child sex may moderate the relations between RSA and child outcomes. Boys with clinical levels of aggressive behavior, for example, exhibited lower resting RSA than boys with lower levels of aggression, although no differences were found for girls (Beauchaine, Hong, & Marsh, 2008). Similar sex differences have been found in community samples with lower resting RSA related to increased externalizing problems for boys (Calkins & Dedmon, 2000) and weaker RSA suppression related to externalizing behavior for boys (Hastings et al., 2008). Sex differences also seem to play a role in the relations between the environment, RSA, and child adjustment. As reported earlier, destructive marital conflict has been found to predict increases in delinquency over time, especially for boys with lower resting RSA and weaker RSA suppression (El-Sheikh et al., 2011).

In summary, the larger body of evidence seems to support some of the hypotheses of the allostatic load theory as indexed via PNS activity. Environmental stressors (e.g., marital conflict) predict lower RSA and weaker RSA suppression responses and could be construed as contributors to allostatic load. In addition, RSA stress responses predict later lower levels of resting RSA, suggesting that “wear and tear” and repeated activation of physiological stress responses, whereas adaptive in the short term, may be related to shifts in biological set points and later maladaptive consequences. Finally, marital conflict has been found to interact with both resting RSA and RSA reactivity to predict maladjustment and symptoms of allostatic overload, such that higher levels of marital conflict in conjunction with lower resting RSA or weaker RSA suppression responses are related to higher levels of problem behavior, especially for boys. Contrasting findings have been reported in the literature, however (Obradovic, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler, & Boyce, 2010).

Longitudinal data are needed to explicitly test the complex and dynamic relations among environmental stressors, physiological stress responses, resting levels of physiological function, and measures of allostatic overload proposed in allostatic load theory. In the current study, we addressed two important questions: (a) whether a dynamic measure of environmental stress (marital conflict and its change over time) would interact with physiological stress responses (RSA-R) such that higher marital conflict or increases in conflict over time in conjunction with greater RSA suppression to stress would be associated with decreases in resting RSA over time (i.e., “wear and tear” of RSA-R in response to environmental stress as contributors to allostatic load), and (b) whether allostatic load (lower initial resting RSA or decreasing RSA over time) would predict symptoms of allostatic overload (higher final levels and increases over time in children’s externalizing behavior). We also explored the role of sex as a moderator in these complex relations; given the novelty of this research question in the proposed context, no hypotheses were advanced regarding differential effects for boys in comparison to girls. Because race has been associated with RSA (with African American children exhibiting higher resting RSA; Hinnant et al., 2011) and externalizing behavior (Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994), it was controlled for in our analyses. Because we combined data from two samples, variability in outcomes due to differences in study sample was controlled.

Method

Participants

Data for the current study come from two independent three-wave data sets used to examine relations between familial stress and children’s development. For both studies, participants included school-aged children and their parents. Families with children diagnosed with a chronic illness, a learning disability, mental retardation, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were excluded from each study. Eligibility criteria required parents to have been living together for at least 2 years. For Study 1, 166 children participated during the first wave of data collection (T1), 132 participated at T2 (80% of the original sample), and 113 participated at T3 (86% of those who participated at T2). For Study 2, participants were 251 children at T1, 217 at T2 (86% of the original sample), and 183 at T3 (84% of those who participated at T2). For Study 1, therewas approximately a 2-year lag between Waves 1 and 2 and a 3-year lag between Waves 2 and 3; Study 2 had a 1-year lag between successive waves. Reasons for attrition in both studies included the inability to be located, hectic schedules, lack of interest, and geographic relocation.

Because of the similarity in sample characteristics and study designs, the two samples were aggregated to create a larger sample and one additional time point of measurement (i.e., a total of four time points). Such combined-sample, accelerated designs have been found to approximate true longitudinal designs (Bell, 1953; Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 1996; Stanger, Achenbach, & Verhulst, 1994). The total sample was comprised of 413 children (219 boys, 194 girls) and was 67% European American and 33% African American. Families were from a wide range of socioeconomic status backgrounds, based on Hollingshead criteria (Hollingshead, 1975) and the median family income was in the $35,000 to $50,000 range. In analyses, we controlled for any differences that may be due to the particular study features in which children participated (i.e., created a variable with two levels: Study 1 and Study 2 and included it as a control in all analyses).

Because each study consisted of three waves, each child could contribute data up to three time points (see Table 1). Children’s data were sorted based on their chronological age, rather than each study’s data collection wave. This approach minimized variability in age within time points and maximized the measurement of true developmental change (Duncan et al., 1996). Children who contributed information between the ages of 7.5 and 8.5 were sorted into the first assessment (age 8, M = 8.13, SD = 0.33); children between the ages of 8.51 and 9.5 were sorted into the second assessment (age 9, M = 8.98, SD = 0.28); children between the ages of 9.51 and 10.5 were sorted into the third assessment (age 10, M = 10.05, SD = 0.31); and finally children who contributed information between the ages of 10.51 and 12.5 were sorted into the fourth assessment (age 11, M = 11.03, SD = 0.45). Because of the small sample size available for children 13 years and older and the increased variability in age, we did not include data from children older than 12.5 in the fourth assessment, lest it obscure developmental change due to the increased variability in age (n = 92, M age = 13.73, SD = 0.54).

Table 1.

Longitudinal data contributed from two studies

| Child Age (Years) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| Study 1 (n) | 47 | 116 | 33 | 26 |

| Study 2 (n) | 175 | 204 | 160 | 73 |

| Total (n) | 222 | 320 | 193 | 99 |

Procedure and measures

For both studies, approval from the university’s internal review board was granted. Procedures are nearly identical across both studies unless otherwise indicated (for more information on each study’s procedures, see El-Sheikh et al., 2009). Samples 1 and 2 corresponded to the same studies described in El-Sheikh et al. (2009). Families visited our university-based research laboratory during each study wave. Parents and children completed several questionnaires about themselves and their family. Mothers and fathers self-reported on questionnaires, whereas children completed the questionnaires via interview with a trained researcher. In addition, children’s physiological responses (i.e., RSA) were assessed while being presented with two independent mildly stressful tasks. Prior to the physiological session, a researcher talked with the families and answered questions to reduce any anxiety. Electrodes were placed on the chest and on the sides of the child’s upper body while at least one parent was present. Next, the researcher left the room and a 6-min adaptation period occurred followed by a 3-min baseline assessment. The researcher then presented the child with two laboratory tasks, each lasting 3 min, with a recovery period between conditions. In the first task, children listened to an audiotape recording of an argument between two adults, which is considered a mild social stressor.

Following the argument, a 3-min recovery period occurred followed by a second 3-min baseline for both studies, with one exception; at T1 in Study 1, a 12-min recovery period (vs. 6-min recovery) occurred between the argument task and the star-tracing task. Children were then presented with the star-tracing task, which is a frustrating and well-established cognitive stressor. The examination of children’s responses to both social and nonsocial stressors can provide greater specificity about the role of psychophysiological responses (Chen, Matthews, Salomon, & Ewart, 2002). For the star-tracing task, one piece of paper that contained the outline of a star was placed in front of the child on a writing tray. Children traced the star for 3 min while only looking through a mirror that was attached to the writing tray (Mirror Tracer, Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN). The star was blocked from direct view but visible through the mirror. The star-tracing task is a well-established nonsocial laboratory challenge (Matthews, Rakaczky, Stoney, & Manuck, 1987; Matthews, Woodall, & Stoney, 1990), and has been linked with individual differences associated with family risk and child adjustment (El-Sheikh et al., 2007).

Marital conflict

For a thorough assessment of marital conflict, both parent and child reports were collected at each study wave. Parents completed the widely used Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). The CTS2 assesses the frequency of numerous conflict tactics used between romantic partners and has demonstrated psychometric qualities (Straus et al., 1996). To reduce biases related to self-reports of marital conflict, mothers’ and fathers’ reports of their spouses’ conflict tactics toward them within the last year were used in analyses (e.g., Ehrensaft & Vivian, 1996). Specifically, the psychological/verbal aggression and physical aggression scales were pertinent to the current study. For each item, parents rated how frequently their partner used the specified type of conflict tactic within the last year (e.g., My partner insulted or swore at me). A score of 1 indicates the specific type of conflict occurred once in the past year (2 = twice, 3 = 3–5 times, 4 = 6–10 times, 5 = 11–20 times, 6 = more than 20 times in the past year). Cronbach alphas indicated good internal consistency for parents and ranged from 0.71 to 0.96.

Via interview, children reported on their parents’ marital conflict via the CTS2. Children reported on each parents’ use of psychological and physical aggression toward their spouse within the last year. Cronbach alphas indicated good internal consistency and ranged from 0.84 to 0.95. As is common in many studies, parent- and child-reported psychological and physical aggression were averaged to create an overall marital conflict variable (e.g., El-Sheikh et al., 2009).

Pearson correlations indicated that mother and father reports of marital conflict were significantly correlated at each wave (rs = .17–.47) and in the majority of cases, child reports of marital conflict were significantly correlated with parent reports (statistically significant rs = .19–.39). To reduce the number of analyses and the likelihood of Type 1 error, child and parent reports of marital conflict were averaged together to create one marital conflict variable. Higher scores reflect higher levels of marital conflict.

RSA data acquisition and reduction

During each study wave, children’s RSA was assessed following standard guidelines (Berntson et al., 1997). Two electrocardiography (ECG) electrodes were placed on the rib cage, about 10 to 15 cm below the armpits. To ground the signal, a third electrode was placed on the center of the chest. A pneumatic bellows was firmly placed around the chest to measure respiratory changes. The ECG signal was digitized at a sampling rate of 1000 readings per second using bandpass filtering with half power cutoff frequencies of 0.1 and 1000 Hz and a gain of 500. The Interbeat Interval (IBI) Analysis System from the James Long Company (Caroga Lake, NY) was used to process the ECG signal. To minimize phase or time shifts in the assessment of respiration, a pressure transducer with a bandpass of DC to 4000 Hz was used with the bellows.

Identification of R-waves was provided via an automated algorithm. In the rare case that it was needed, an interactive graphical program was used for manual correction of misidentified R-waves. R-wave times were then converted to IBIs and resampled into equal time intervals of 125 ms. All IBIs that spanned the 125-ms interval were prorated. The program prorates at every eighth of a second. The prorated IBIs were stored for computation of the mean and variance of heart period as well as assessing heart period variability due to RSA. RSA at baseline and during the challenge situations (i.e., interparental argument and the star-tracing task) were calculated for the entire epoch.

RSA was calculated using the peak-to-valley method and all units were in seconds; prior work has indicated this method to be one of several acceptable approaches for quantifying RSA (Bernston et al., 1997). The peak to valley method is highly correlated with changes in RSA from either surgical blockades or pharmacological use, and with spectrally derived measures of RSA (Galles, Miller, Cohn, & Fox, 2002). The peak to valley method can also determine RSA reactivity (RSA-R) during brief periods (Berntson et al., 1997). RSA was computed by using the difference in IBI readings from inspiration to expiration onset. Because baseline RSA levels can impact RSA-R (law of initial values), RSA-R was calculated as a residualized change score (obtained through regressing baseline RSA on RSA during the challenge tasks). Lower values for RSA-R are indicative of greater RSA suppression in response to either of the challenge conditions.

Children’s externalizing symptoms

During each study wave, mothers and fathers each reported on their child’s externalizing symptoms via the widely used Personality Inventory for Children II (PIC2; Lachar & Gruber, 2001). The Externalizing Scale was pertinent to the current investigation and assesses children’s impulsivity, aggression, disruptive behavior, noncompliance, as well as delinquency. For each item, response choices consist of true/false, with higher scores reflective of more externalizing symptoms. The PIC2 is particularly useful for community samples, as prior research has demonstrated the measure to be sensitive in detecting externalizing symptoms among children below the clinical range (e.g., El-Sheikh, 2001). The PIC has demonstrated very good psychometric properties including interrater reliability, test–retest reliability, construct validity, and discriminant validity (Lachar & Gruber, 2001; Wirt, Lachar, Klinedinst, & Seat, 1990). At each wave, mothers’ and fathers’ reports were significantly correlated (rs = .39–.84) and consequently were mean composited to create one overall children’s externalizing symptoms score at each wave. For the current study, Cronbach alphas ranged from 0.85 to 0.98. Although we used raw scores in analyses (as recommended for growth modeling; Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2006), proportions of children with borderline or clinical levels of externalizing symptoms (T > 60) at ages 8, 9, 10, and 11 were 8%, 11%, 10%, and 7%, respectively.

Plan of analysis

We first constructed a multiple domain unconditional growth model (see Curran & Willoughby, 2003; Keiley, Martin, Liu, & Dolbin-MacNab, 2005) for marital conflict, RSA, and externalizing symptoms from ages 8 to 11. Although it was possible to model nonlinear change, this additional component was excluded due to the complex nature of the model. In order to most appropriately answer our research questions, the intercept for marital conflict and RSA were set at the initial time point (age 8) and time was coded to be interpreted in relation to increases in marital conflict and RSA over time (slope time coding of 0, 1, 2, 3), whereas the intercept for externalizing symptoms was set to the final time point (age 11); time was coded so that the slope counted down to that final level (coding of −3, −2, −1, 0; Biesanz, Deeb-Sousa, Papadakis, Bollen, & Curran, 2004).

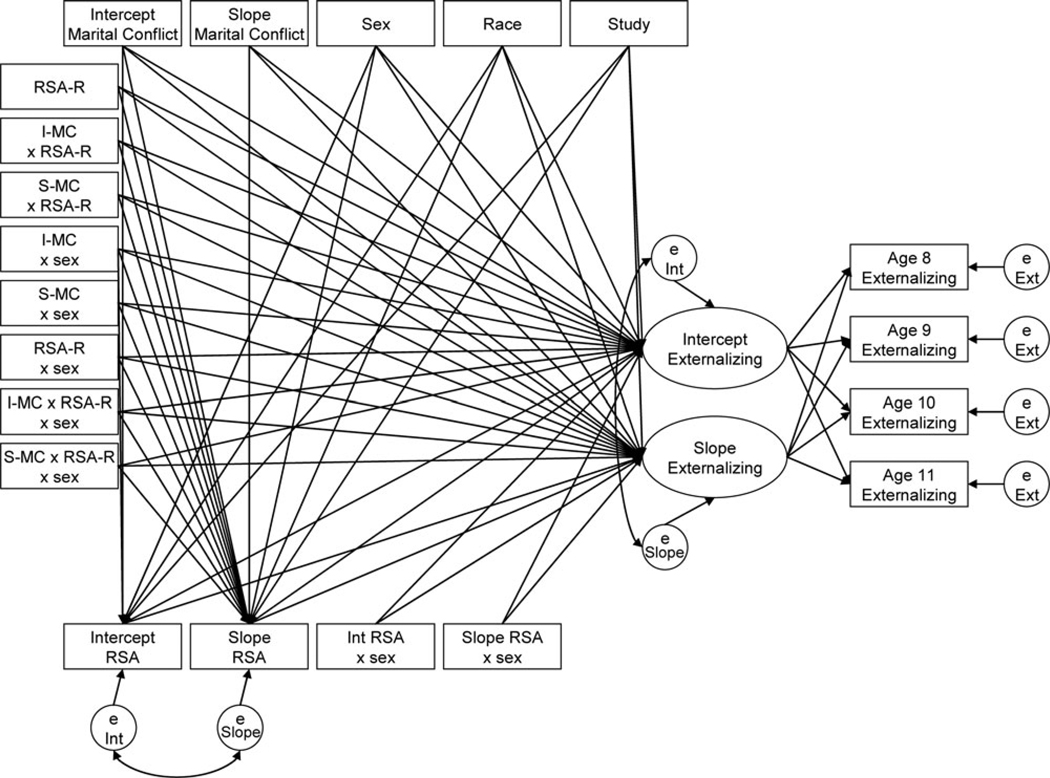

Next, we tested our substantive research questions in a conditional model. The main research questions, that of predicting levels and change in children’s RSA from marital conflict, RSA-R, sex, and their interactions, and that of predicting levels and change in children’s externalizing behavior from levels and change in RSA, sex, and their interactions, were estimated simultaneously in a single model (Figure 1). Because of the complex nature of the conditional model using marital conflict and RSA as predictors, factors scores for intercepts and slopes of marital conflict and RSA obtained from the unconditional model were used (instead of the latent intercept and slopes). The use of factor scores instead of latent variables is an acceptable method of simplifying complex models so that they can be successfully estimated (Curran, Edwards, Wirth, Hussong, & Chassin, 2007). To facilitate interpretation, time invariant continuous variables were mean centered and dichotomous variables were coded as 0 or 1 (Aiken & West, 1991). To minimize multicolinearity among interaction terms, interactions were residual centered (Lance, 1988; Little, Bovaird, & Widaman, 2006). In this process, each interaction was regressed on its constituent variables and, if applicable, its lower order interaction terms. The unstandardized residual scores of the interaction terms were used in the conditional model. Significant interactions were plotted at ±1 SD and simple slopes were tested to evaluate whether they were significantly different from zero (Aiken & West, 1991; Curran, Bauer, & Willoughby, 2004).

Figure 1.

The model for predicting levels and change in children’s respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) from marital conflict, RSA reactivity (RSA-R), sex, and their interactions and for predicting levels and change in children’s externalizing behavior from levels and change in RSA, sex, and their interactions.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. Repeated measures (i.e., marital conflict, RSA, and externalizing behavior) were correlated within domains. Marital conflict was positively associated with externalizing symptoms at most time points. Boys were exposed to higher levels of marital conflict at ages 8 and 9. In addition, boys exhibited higher levels of externalizing symptoms at ages 8, 9, and 11. RSA suppression was the most common response to the star-tracing task with 74% of children exhibiting some decrease in RSA during the task. RSA-R was positively related to resting RSA at ages 10 and 11 (i.e., children who showed weaker RSA suppression to the star tracing task had higher later resting RSA). Finally, RSA-R was positively related to externalizing symptoms at ages 10 and 11 (children who showed weaker RSA suppression to the star tracing task had higher externalizing symptoms at ages 10 and 11).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Study | — | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Sex (boys = 1, girls = 0) | .05 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Race (AA = 1, EA = 0) | .04 | −.04 | — | |||||||||||||

| 4. Marital conflict age 8 | .01 | .14* | −.06 | — | ||||||||||||

| 5. Marital conflict age 9 | −.03 | .20* | −.08 | .25* | — | |||||||||||

| 6. Marital conflict age 10 | −.03 | −.03 | .01 | .40* | .39* | — | ||||||||||

| 7. Marital conflict age 11 | −.04 | −.01 | .15* | .31* | .27* | .46* | — | |||||||||

| 8. RSA baseline age 8 | .09 | .06 | .23* | .03 | −.06 | .11 | .18 | — | ||||||||

| 9. RSA baseline age 9 | .17* | .04 | .06 | .03 | .03 | .02 | .05 | .63* | — | |||||||

| 10. RSA baseline age 10 | .07 | .11 | .10 | .04 | −.02 | .04 | .01 | .54* | .64* | — | ||||||

| 11. RSA baseline age 11 | .15 | .04 | .18* | −.19* | .27* | −.02 | .07 | .32* | .39* | .50* | — | |||||

| 12. RSA reactivity age 8 | .09 | .04 | .03 | −.09 | −.01 | −.05 | .06 | — | .11 | .19* | .20* | — | ||||

| 13. Externalizing age 8 | −.00 | .18* | −.02 | .29* | .15 | .09 | .09 | .07 | .03 | −.05 | −.02 | .01 | — | |||

| 14. Externalizing age 9 | .01 | .18* | −.01 | .29* | .34* | .18* | .09 | −.04 | −.02 | −.11 | .22* | .05 | .75* | — | ||

| 15. Externalizing age 10 | .14* | .13 | −.07 | .35* | .22* | .23* | .19 | −.06 | −.06 | .02 | .23* | .19* | .84* | .79* | — | |

| 16. Externalizing age 11 | .10 | .17* | −.07 | .13 | .25* | .13 | .17* | −.11 | −.07 | −.01 | .11 | .20* | .70* | .49* | .82* | — |

| M | — | — | — | 3.60 | 3.54 | 3.71 | 3.26 | 15.73 | 14.98 | 15.80 | 14.60 | .00 | 4.32 | 4.53 | 4.71 | 4.14 |

| SD | — | — | — | 2.49 | 3.23 | 4.79 | 3.99 | 9.26 | 7.63 | 8.11 | 8.09 | .06 | 3.48 | 3.78 | 4.04 | 3.91 |

Note: Study 1 was coded as 0; Study 2 was coded as 1. AA, African American; EA, European American; RSA, respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity is in reference to reactivity occurring during the star-tracing task.

p < .05.

Unconditional growth

To simplify the model, error variances for repeated measures within constructs (e.g., marital conflict at each time point) were constrained to be equal (Duncan et al., 2006). This constraint did not significantly worsen model fit. Covariances were estimated between each latent intercept and its respective slope only; predictive relations among intercepts and slopes across variables were tested in the conditional model. The unconditional growth model demonstrated acceptable fit as indicated by the root mean square error of approximation with 90% confidence intervals extending from 0.067 to 0.088 (values of 0.08 or less are considered to indicate acceptable fit; Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Table 3 depicts unconditional model fit and parameters. Initial marital conflict was positively related to the slope (r = .45, p <.01), indicating that children who witnessed more marital conflict at age 8 tended to experience increases in parental marital conflict over time. Children who had higher initial RSA were more likely to show decreases in RSA over time (r = −.60, p < .01). Finally, children who exhibited increases in externalizing symptoms over time also tended to have higher levels of externalizing symptoms at age 11 (r = .54, p < .01). The average slopes for marital conflict, children’s RSA, and externalizing symptoms did not show significant change over time. All intercepts and slopes, however, exhibited significant variability (all ps < .001). This variability indicated that it would be possible to predict levels and change over time in RSA and externalizing symptoms (Duncan et al., 2006).

Table 3.

Parameter estimates and standard errors for the unconditional growth model of marital conflict, RSA, and externalizing symptoms

| Intercept Factor |

Slope Factor |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | RMSEA | χ2 | df | χ2/df | p |

| 3.71** | 0.17 | −0.16 | 0.12 | ||||||

| Marital conflict | (1.76**) | (0.59) | (1.02**) | (0.22) | 0.078 | 253.85 | 72 | 3.48 | <.01 |

| 15.07** | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.24 | ||||||

| RSA | (52.03**) | (7.04) | (5.86**) | (1.77) | |||||

| 4.30** | 0.25 | −0.09 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Externalizing symptoms | (15.07**) | (1.65) | (0.69**) | (0.21) | |||||

Note: The intercepts of marital conflict and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) are set at the beginning of data collection (age 8), and slopes represent change from that point. The intercept of externalizing symptoms was set to the end of data collection, (age 11), and the slope represents change to that point. Average intercept and slope values and their standard errors are listed without parentheses. Variability estimates of the intercept and slope and their standard errors are given in parentheses. RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Conditional growth

Our conditional growth model is presented in Figure 1. This model displayed acceptable fit indexes, χ2 (135) = 354.94, p < .01, χ2/df = 2.63, root mean square error of approximation = .063, 90% confidence interval = 0.055 to 0.071. Our first research question addressed whether marital conflict and its change over time (stress), RSA reactivity (stress response), sex, and their interactions predicted levels and change over time in resting RSA (allostatic load).1 Full results can be found in Table 4. Note that only some of the variables were set to predict initial levels of RSA; conceptually, it made sense to predict only initial levels of RSA from initial levels of marital conflict and the Marital Conflict × Sex interaction.2 RSA-R was excluded because initial levels of resting RSA were used in its calculation (i.e., reactivity was computed as a residualized change score). All other variables not predicting initial RSA were excluded because they were measured at later time points (i.e., temporal precedence). The only significant predictors of initial levels of RSA were the child’s ethnicity and specific study (i.e., Study 1 or 2). African American children had significantly higher initial RSA than European American children, and children in Study 2 exhibited higher initial RSA than children in Study 1. The total model explained 4.6% of variance in children’s initial RSA.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates and standard errors for predicting RSA

| RSA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept |

Slope |

|||||||

| Predictor | B | SE | β | p | B | SE | β | p |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Sex | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.05 | .27 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.01 | .86 |

| Race | 1.77 | 0.58 | 0.15 | <.01 | −0.08 | 0.13 | −0.03 | .57 |

| Study | 1.43 | 0.56 | 0.12 | .01 | −0.08 | 0.13 | −0.03 | .55 |

| Main Effects | ||||||||

| I-MC | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.03 | .52 | −0.09 | 0.11 | −0.04 | .40 |

| S-MC | — | — | — | — | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.02 | .62 |

| RSA-R | — | — | — | — | 1.55 | 0.85 | 0.08 | .07 |

| Two-Way Interactions | ||||||||

| I-MC × RSA-R | — | — | — | — | −0.27 | 1.62 | −0.01 | .87 |

| S-MC × RSA-R | — | — | — | — | −2.22 | 1.96 | −0.06 | .26 |

| I-MC × Sex | 1.35 | 0.87 | 0.08 | .12 | −0.40 | 0.22 | −0.10 | .07 |

| S-MC × Sex | — | — | — | — | −0.01 | 0.18 | −0.01 | .96 |

| RSA-R × Sex | — | — | — | — | 3.04 | 1.86 | 0.07 | .10 |

| Three-Way Interactions | ||||||||

| I-MC × RSA-R × Sex | — | — | — | — | −8.05 | 3.25 | −0.12 | .01 |

| S-MC × RSA-R × Sex | — | — | — | — | 11.53 | 4.23 | 0.14 | <.01 |

| Total R2 | .046 | .047 | ||||||

Note: RSA, respiratory sinus arrhythmia; I-Mc, initial marital conflict; S-MC, slope of marital conflict; RSA-R, RSA reactivity.

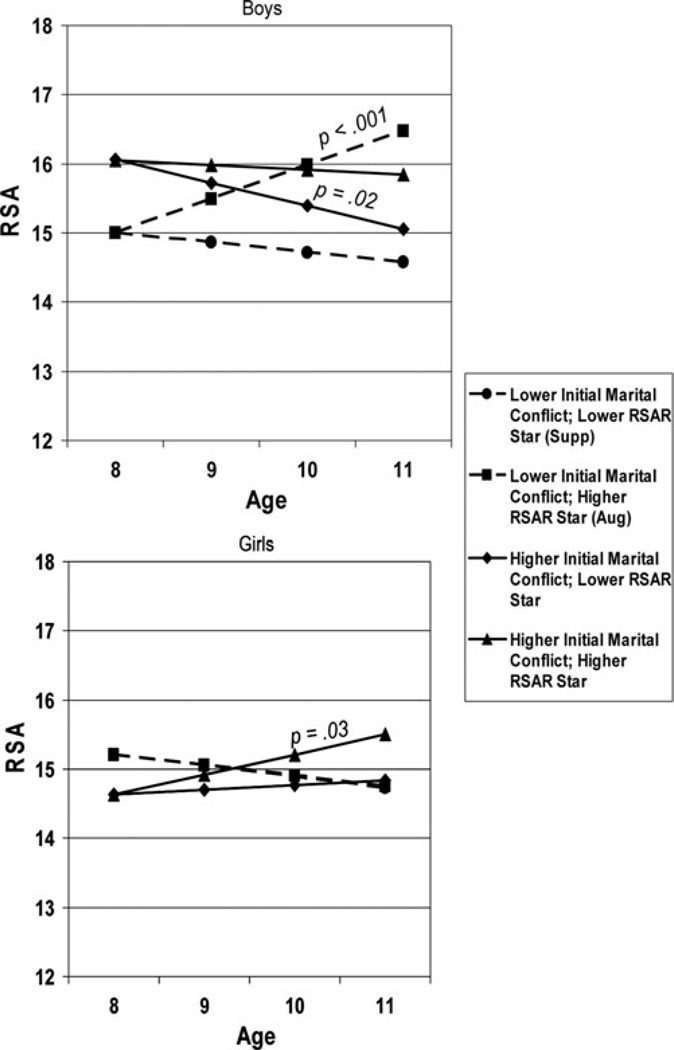

The only variables to predict change over time in RSA were the three-way interactions. The first of these, initial Marital Conflict × RSA-R × Sex, is represented in Figure 2. Plotting the simple slopes revealed that boys who experienced lower levels of initial marital conflict and who exhibited RSA augmentation in response to the frustrating, star-tracing laboratory stressor showed significant increases in their resting RSA over time. Boys who experienced higher initial levels of marital conflict and who exhibited a strong RSA suppression response to the lab stressor showed significant declines in resting RSA over time. Girls who experienced higher initial marital conflict and exhibited RSA augmentation to the lab stressor showed significant increases in resting RSA over time.

Figure 2.

The change in baseline respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) over time is predicted by the interaction between initial levels of marital conflict, RSA reactivity (RSA-R), and sex.

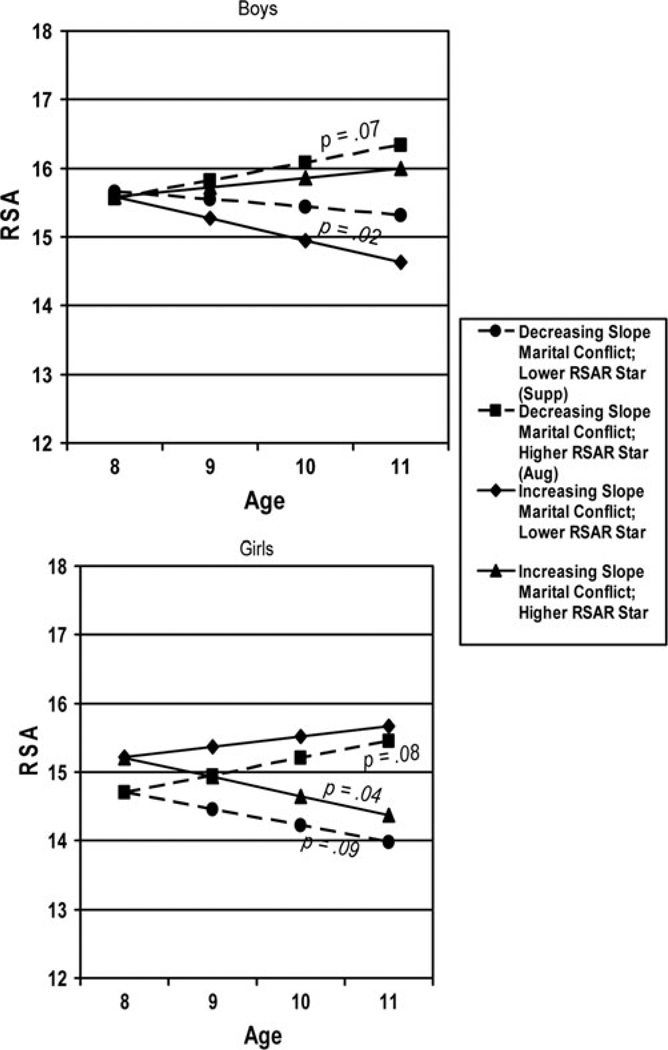

The second interaction, change over time in Marital Conflict × RSA-R × Sex, is presented in Figure 3. Boys who experienced increasing levels of marital conflict over time and who showed a strong RSA suppression response to the lab stressor exhibited decreases in their resting RSA over time. In contrast, girls who experienced increases in marital conflict over time and who exhibited RSA augmentation in response to the lab stressor showed decreases in their resting RSA over time. These three-way interactions accounted for 2% of the unique variance in the slope of RSA and the total model accounted for 4.7% of variance in the change over time in children’s RSA.

Figure 3.

The change in baseline respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) over time is predicted by the interaction between the slope of marital conflict, RSA reactivity (RSA-R), and sex.

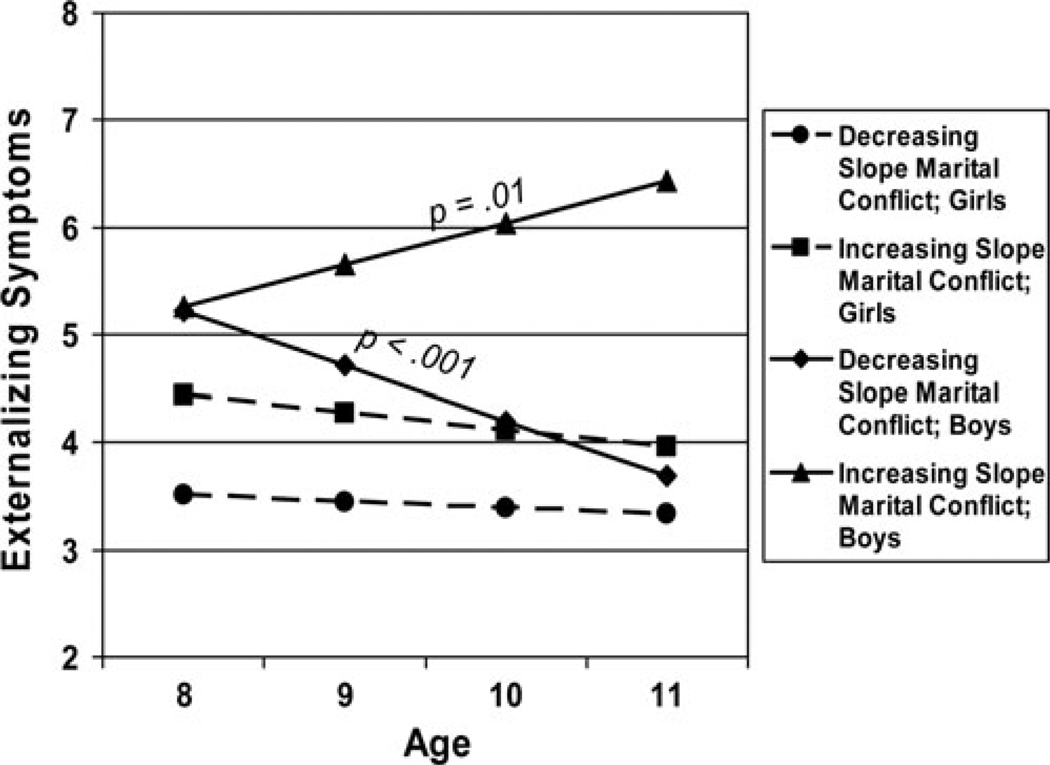

Our second research question consisted of two parts. In the first part we attempted to answer the question of whether environmental stress (initial marital conflict and its change over time), physiological stress response (RSA reactivity), and sex predict or interact to predict behavior (change over time in and final levels of externalizing symptoms). Parameter estimates predicting externalizing symptoms are presented in Table 5. It can be seen that increases in marital conflict over time predicted increases in externalizing symptoms over time and higher final levels of externalizing symptoms. This finding was qualified by an interaction involving change over time in marital conflict (i.e., slope) and child sex. Girls showed no significant change in their externalizing symptoms over time, regardless of the level of change in marital conflict over time. In contrast, boys who experienced significant declines in marital conflict over time evidenced significant decreases in externalizing symptoms, whereas boys who experienced increasing levels of marital conflict over time exhibited significant increases in their externalizing symptoms longitudinally (Figure 4). The interaction accounted for 9% of the unique variance in the slope of externalizing symptoms and less than 1% of the unique variance in the intercept (final levels) of externalizing symptoms. There was, however, no evidence of Stress × Stress Response or Stress × Stress Response × Sex interactions for externalizing symptoms.

Table 5.

Parameter estimates and standard errors for predicting externalizing symptoms

| Externalizing Symptoms | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept |

Slope |

|||||||

| Predictor | B | SE | β | p | B | SE | β | p |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Sex | 1.32 | 0.46 | 0.17 | <.01 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.02 | .86 |

| Ethnicity | −0.56 | 0.49 | −0.07 | .26 | −0.22 | 0.17 | −0.14 | .19 |

| Study | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.04 | .47 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.02 | .83 |

| Main Effects | ||||||||

| I-MC | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.04 | .59 | −0.11 | 0.14 | −0.10 | .41 |

| S-MC | 1.26 | 0.38 | 0.22 | <.01 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.25 | .03 |

| RSA-R | 5.87 | 3.69 | 0.10 | .11 | 1.47 | 1.28 | 0.13 | .25 |

| I-RSA | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.14 | .05 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.27 | .03 |

| S-RSA | −0.06 | 0.78 | −0.02 | .78 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.02 | .90 |

| Two-Way Interactions | ||||||||

| I-MC × RSA-R | 6.03 | 6.99 | 0.07 | .39 | 0.21 | 2.42 | 0.01 | .93 |

| S-MC × RSA-R | −2.08 | 8.48 | −0.02 | .81 | −0.93 | 2.93 | −0.04 | .75 |

| I-MC × Sex | 0.38 | 0.83 | 0.03 | .65 | −0.47 | 0.29 | −0.20 | .10 |

| S-MC × Sex | 1.36 | 0.78 | 0.12 | .08 | 0.74 | 0.27 | 0.33 | <.01 |

| RSA-R × Sex | 6.54 | 8.03 | 0.05 | .42 | 1.43 | 2.78 | 0.06 | .61 |

| I-RSA × Sex | −0.14 | 0.08 | −0.10 | .09 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.28 | <.01 |

| S-RSA × Sex | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.09 | .11 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.07 | .48 |

| Three-Way Interactions | ||||||||

| I-MC × RSA-R × sex | −15.21 | 14.15 | −0.08 | .28 | −1.94 | 4.89 | −0.05 | .69 |

| S-MC × RSA-R × sex | −1.12 | 18.44 | −0.01 | .95 | −3.96 | 6.37 | −0.08 | .53 |

| Total R2 | .17 | .37 | ||||||

Note: I-Mc, initial marital conflict; S-MC, slope of marital conflict; RSA-R, respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity; I-RSA, initial RSA; S-RSA, slope of RSA.

Figure 4.

The change in externalizing symptoms is predicted by the interaction between the slope of marital conflict and sex.

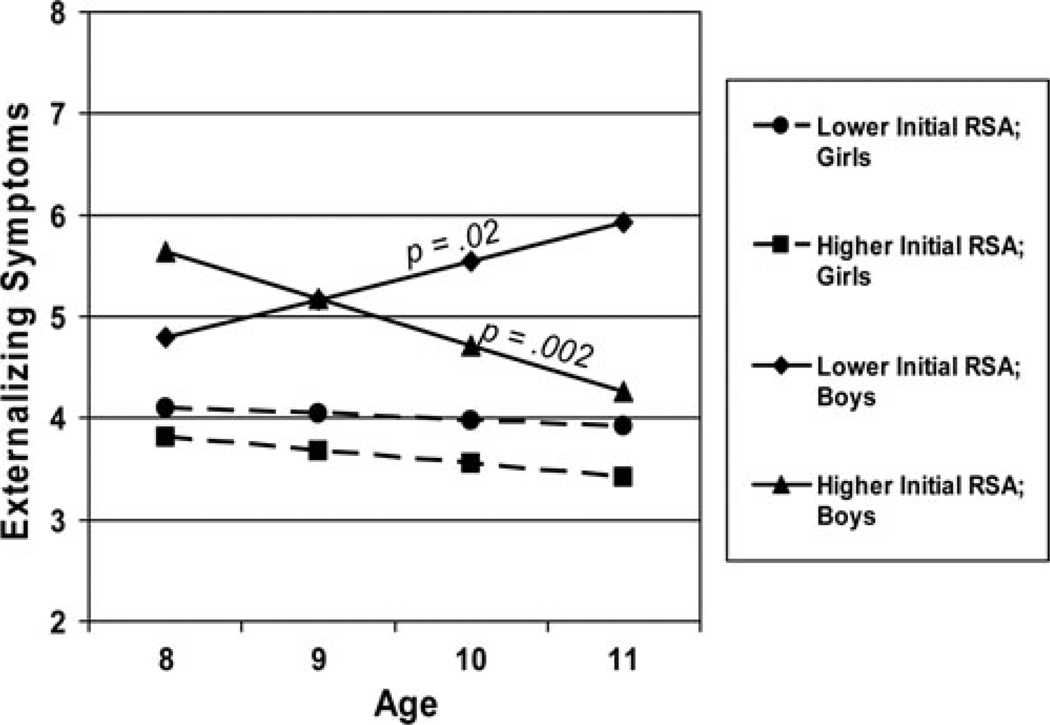

The second part of the question addressed whether allostasis and allostatic load (resting RSA and its change over time) predicted or interacted with sex to predict the development of children’s externalizing symptoms, after accounting for the original stressor, physiological stress response, and interactions. In essence, we asked whether the allostatic process is important in predicting maladaptive behavior once the original stressors and responses were taken into account. Table 5 shows that higher initial levels of RSA predicted decreases in externalizing symptoms over time and lower final level levels of externalizing symptoms. This finding was qualified by an interaction with sex. Girls’ externalizing symptoms did not show any significant change, regardless of their initial levels of RSA. Boys with higher initial RSA exhibited significant declines in their externalizing symptoms over time, whereas boys with lower initial RSA exhibited significant increases in their externalizing symptoms over time (Figure 5). This interaction accounted for 7% of unique variance in the slope of externalizing symptoms and a negligible portion of variance in the intercept. Change over time in RSA did not directly predict or interact with sex to predict externalizing symptoms. The full model accounted for 37% of the variance in the slope of externalizing symptoms and 17% of the variance in the intercept of externalizing symptoms.

Figure 5.

The change in externalizing symptoms is predicted by the interaction between initial levels of baseline respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) and sex.

Discussion

In the current study, we built upon prior research on allostatic load (McEwen & Stellar, 1993) by exploring a physiological system that has less often been considered in this area, PNS activity as indexed by RSA. We used a large community sample of children with longitudinal data to test the complex and dynamic hypotheses of allostatic load theory in a more explicit manner than has most commonly been the case in this area of study. Although a number of studies have supported different aspects of allostatic load theory, some studies have been limited by a lack of longitudinal data (and thus could not test the dynamic relations hypothesized), did not specifically adopt an allostatic load approach in their study (and so did not explicitly test all aspects of the theory), or have been generally more piecewise in testing the theory. Our findings indicate that marital conflict interacted with RSA reactivity and sex to predict resting RSA over time; this is the first such demonstration in the literature. In addition, resting RSA interacted with sex to predict changes in externalizing symptoms longitudinally. Next, we discuss our primary findings in greater detail and the strengths and weaknesses of the study.

We tested the hypothesis that a family stressor, marital conflict, and its change over time, would predict our measure of allostatic load, RSA, and its change over time. Because physiological stress responses are also hypothesized to be an important part of understanding allostatic load, we also tested whether RSA reactivity to stress predicted or interacted with marital conflict to predict resting RSA and its change longitudinally. Finally, we investigated whether child sex functioned as another potential moderator. Our results supported this initial hypothesis only for boys. Specifically, boys who experienced initially higher marital conflict or increases in marital conflict over time and who exhibited a strong RSA suppression stress response to the star-tracing task had decreasing RSA over time. Although RSA suppression is a protective factor for children’s adjustment in the context of family adversity (e.g., El-Sheikh et al., 2001; El-Sheikh & Whitson, 2006), it may also contribute to shifts in resting RSA over time (see also Salomon et al., 2000). Such a stressor (Marital Conflict) × Stress Response (RSA suppression) interaction is consistent with allostatic load theory; repeated, adaptive disengagement of RSA (i.e., suppression) in coping with stressors may contribute to wear and tear and eventual dysregulation in this aspect of PNS function (McEwen & Stellar, 1993). In the absence of environmental stress, however, our results also indicate that individuals who exhibit less adaptive RSA stress responses may show increases in resting RSA over time, a process that may be a form of physiological recovery. Notably, these findings would also seem to support another recent theory focusing on biological sensitivity to context (Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Ellis & Boyce, 2008). Briefly stated, the theory posits that increased biological sensitivity to stress is detrimental to adaptation in the context of harsh environments but adaptive in the context of protective environments. Future crafting of theory in this area may benefit from integrating these two distinct but related theories.

As mentioned earlier, other stress coping responses are also likely to contribute to allostatic load and symptoms of allostatic overload that may manifest as maladaptive behavior. In particular, effective cognitive or emotional stress coping responses may be facilitated by or reflected in adaptive physiological coping (e.g., Davies, Sturge-Apple, Cicchetti, & Cummings, 2008). It is possible that underlying the sex differences in our results are the cognitive and emotional coping responses that are employed by girls and boys. There is some evidence that girls are better at cognitive and emotional self-regulation and coping (e.g., Brody, 2000), whereas the effects of physiological regulation for boys are more apparent, important, and readily related to allostatic load.

In testing our second hypothesis, we investigated whether allostatic load, indexed by RSA, predicted or interacted with sex to predict symptoms of allostatic overload as indexed by children’s externalizing behavior. Consistent with allostatic load theory, we hypothesized that lower initial resting RSA or decreases in RSA over time would be related to increases in externalizing behavior over time and higher final levels of externalizing behavior. This particular hypothesis was only partially supported. Although change in RSA over time did not predict externalizing behavior, initial RSA was found to interact with sex to predict change over time in externalizing behavior such that boys with lower RSA exhibited increases in externalizing behavior over time. These findings are reminiscent of those obtained in both community (Calkins & Dedmon, 2000) and clinical samples (Beauchaine et al., 2008) and extend them to the development of externalizing behavior. It is conceivable that individuals who show decreases in resting RSA over time (perhaps boys especially) are increasing their physiological risk for maladaptive behavior, but the developmental time frame assessed in this study was not wide enough to capture the full allostatic load process. These findings are exciting and raise many questions regarding dynamic interactions between biology and environment in the development of symptoms of psychopathology. These questions to be answered in future research are tied to limitations in the study’s methodology as outlined below.

We chose to investigate the role of one dynamic stressor and its relations to allostatic load, whereas many studies have directed their efforts toward studying the cumulative effects of multiple environmental stressors (see Juster et al., 2010). Although our findings supported our hypotheses, it is also clear that investigation of other environmental stressors as predictors is important in understanding individual differences in allostatic load. Our choice was tied to our studies’ primary research focus, marital conflict, and its relations to child adjustment, and to the methodological difficulties inherent in constructing a dynamic cumulative risk index. For example, variable-centered cumulative risk indexes require that all risks be set to a common scale (usually a z score) so that they can be summed, but z scores are not appropriate for dynamic analyses such as latent growth modeling because the metric is reset at each time point and has a constant mean of zero (Burchinal, Nelson, & Poe, 2006; Willett, Singer, & Martin, 1998). Recent work on person-centered approaches, however, offers some insight into how an index of dynamic, cumulative, person-centered risk might be achieved (Lanza, Rhoades, Nix, Greenberg, & The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2010; Parra, DuBois, & Sher, 2006). Utilizing such an approach may reveal how patterns of environmental risk relate to different types of psychopathology (Shanahan, Copeland, Costello, & Angold, 2008). In addition, an important avenue for research is to test if environmental stress also predicts changes in physiological stress responses, which may mediate the relations between environmental stress and allostatic shifts, or if environmental stress and physiological stress responses simply interact to predict allostatic load.

A second limitation is that our study used a single index of allostatic load, RSA, rather than multiple physiological indexes (Juster et al., 2010). Modeling multiple physiological indexes of allostatic load was simply beyond the capabilities of our data (i.e., sample size). Adding additional dynamic measures of allostatic load would have further complicated an already complex model. Yet, allostatic load theory suggests that environmental stress and stress responses are related to shifts in function in multiple physiological systems. Similar issues were encountered when we attempted to model marital conflict using mother, father, and child reports as multiple indicators of marital conflict within time points as part of a growth model (see, e.g., Bovaird, 2007; Wu, Liu, Gadermann, & Zumbo, 2009). Thus, it is clear that carefully constructed hypotheses and large longitudinal samples are needed in order to employ the best statistically recommended practices for testing complex growth processes.

The community nature of our sample limits the generalizability of our results. Only a small percentage of our sample exhibited clinical or clinical risk levels of externalizing symptoms (T score > 60). Thus, we do not know if the same developmental processes explored in the current report also apply to children with more severe patterns of behavioral problems. Exploring these developmental processes in both community and clinical samples may help to elucidate if or how developmental processes differ and at what point they may diverge (Cicchetti & Toth, 2009). Ideally, sampling normative and clinical children would be accomplished in a single study, which would facilitate testing differences in development.

Finally, there are implicit assumptions made with any type of analysis, and these assumptions influence the knowledge that can be drawn from a set of results. In using latent growth modeling to test our hypotheses, we made the assumption that all children were from a single population of individuals who followed the same form of growth, although their initial or final levels (intercepts) and change over time were free to vary on an individual basis (Bauer & Curran, 2003; Sterba & Bauer, 2010). Although such a model is fairly nonrestrictive, other analytic approaches that are even more person-oriented (such as growth mixture modeling) may have yielded some different patterns of results (Sterba & Bauer, 2010). Future research in this area may benefit from selectively applying person-centered approaches to address the limitations described in this paper.

Despite the noted shortcomings, this paper makes a significant contribution to the study of allostatic load by addressing an area that has received less attention, PNS function indexed through RSA activity, and by specifically addressing and testing many of the dynamic hypotheses inherent in allostatic load theory. Our results support the hypothesis that environmental stress indexed by marital conflict, and physiological stress responses indexed by RSA reactivity, interact to predict allostatic load marked by resting levels of RSA; this finding was limited to boys. In addition, initial marital conflict (but not its change over time) predicted symptoms of allostatic overload, again only for boys.

These findings have implications for our understanding of developmental biopsychology, the development of psychopathology, and intervention and prevention efforts. A recent multidisciplinary, collaborative effort has attempted to explicate how biological processes could be integrated into prevention and intervention studies (for more information see Cicchetti & Gunnar, 2008, and the associated special issue). Findings from the current report can be specifically related to several of the points raised by Beauchaine and colleagues (2008) in that same issue. First, the current report illustrated how environmental and biological processes may confer risk for the development of psychopathology. Second, these same biological processes are also likely to operate as moderators in how children respond to intervention efforts. Specifically, further understanding of biological developmental and self-regulatory processes may indicate that certain children would especially benefit from targeted intervention efforts especially focused on, for example, teaching children how to self-regulate in the context of conflict (for further review, see Cummings et al., 2009). Third, preventive intervention that includes the biological processes discussed in this paper may eventually be used to potentiate the identification of children at particular risk for developing psychopathology in the context of marital conflict and then indicate the best interventions for these children before the psychopathology develops. Such a preventive intervention has not yet been realized, but remains the ultimate goal of developmental psychopathology (Cicchetti & Gunnar, 2008): helping individuals to modify maladaptive developmental trajectories before they result in long-term problems. Hopefully, future research in this area will continue to illuminate the complex relations among environmental stress, physiological stress responses, and developmental psychopathology processes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Health Grant R01-HD046795 and National Science Foundation Grants 0339115 and 0623936. We thank the staff of our Research Laboratory, most notably Lori Staton and Bridget Wingo, for data collection and preparation, and the school personnel, children, and parents who participated.

Footnotes

No significant results were found in the prediction of initial levels or change in RSA, or in final levels or change in externalizing symptoms, from physiological responses to the argument task. To conserve space, those results are omitted and physiological responses to the argument are not considered further in the current report.

Having relatively few variables predicting initial levels of RSA explains why many of the simple slopes in the figures start at similar values. Fewer significant predictors of a starting value will result in less variability in predicted (or plotted) start values. Thus, part of the model specific to predicting children’s initial RSA is unavoidably misspecified to some degree.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon A, Lippert S, Vujan N, Rodriguez ME, Boyce WT, Eskenazi B. The ontogeny of autonomic measures in 6- and 12-month-old infants. Developmental Psychobiology. 2006;48:197–208. doi: 10.1002/dev.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Marshall PJ, Fox NA. Developmental changes in heart period and high-frequency heart period variability from 4 months to 4 years of age. Developmental Psychobiology. 2000;37:44–56. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(200007)37:1<44::aid-dev6>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Distributional assumptions of growth mixture models: Implications for overextraction of latent trajectory classes. Psychological Methods. 2003;8:338–363. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Gatzke-Kopp L, Mead HK. Polyvagal theory and developmental psychopathology: Emotion dysregulation and conduct problems from preschool to adolescence. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Hong J, Marsh P. Sex differences in autonomic correlates of conduct problems and aggression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:788–796. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172ef4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Neuhaus E, Brenner SL, Gatzke-Kopp L. Ten good reasons to consider biological processes in prevention and intervention research. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:745–774. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. Convergence: An accelerated longitudinal approach. Child Development. 1953;24:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Bigger JT, Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kaufmann PG, Malik M, et al. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT, Quigley KS. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Autonomic origins, physiological mechanisms, and psychophysiological implications. Psychophysiology. 1993;30:183–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1993.tb01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Neuhuber WL. Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2000;85:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesanz JC, Deeb-Sossa N, Papadakis AA, Bollen KA, Curran PJ. The role of coding time in estimating and interpreting growth curve models. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:30–52. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, Van Baal GCM, Orlebeke JF. Genetic influences on respiratory sinus arrhythmia across different task conditions. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Emellologia. 1990;39:181–191. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000005419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Suess PE. Child and mother cardiac vagal tone: Continuity, stability, and concordance across the first 5 years. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:54–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovaird JA. Multilevel structural equation models for contextual factors. In: Little TD, Bovaird JA, Card NA, editors. Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies. New York: Psychology Press; 2007. pp. 149–182. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis B. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary–developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;7:271–301. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR. The socialization of gender differences in emotional expression: Display rules, infant temperament, and differentiation. In: Fischer AH, editor. Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Testing structural equation models: Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Nelson L, Poe M. Growth curve analysis: An introduction to various methods for analyzing longitudinal data. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71:65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Blandon AY, Williford AP, Keane SP. Biological, behavioral, and relational levels of resilience in the context of risk for early childhood behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:675–700. doi: 10.1017/S095457940700034X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Dedmon SE. Physiological and behavioral regulation in two-year-old children with aggressive/destructive behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:103–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1005112912906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Dedmon SE, Gill KL, Lomax LE, Johnson LM. Frustration in infancy: Implications for emotion regulation, physiological processes, and temperament. Infancy. 2002;3:175–197. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Graziano PA, Berdan LE, Keane SP, Degnan KA. Predicting cardiac vagal regulation in early childhood from maternal–child relationship quality during toddlerhood. Developmental Psychobiology. 2008;50:751–766. doi: 10.1002/dev.20344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Graziano PA, Keane SP. Cardiac vagal regulation differentiates among children at risk for behavior problems. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Keane SP. Cardiac vagal regulation across the preschool period: Stability, continuity, and implications for childhood adjustment. Developmental Psychobiology. 2004;45:101–112. doi: 10.1002/dev.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon W. Organization for physiological homeostasis. Physiological Reviews. 1929;9:399–431. [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Matthews KA, Salomon K, Ewart CK. Cardiovascular reactivity during social and nonsocial stressors: Do children’s personal goals and expressive skills matter? Health Psychology. 2002;21:16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie IC, Friedman BH. Autonomic specificity of discrete emotion and dimensions of affective space: A multivariate approach. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2004;51:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Gunnar MR. Integrating biological measures into the design and evaluation of preventive interventions. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:737–743. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The past achievements and future promises of developmental psychopathology: The coming of age of a discipline. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C, Fox NA, Usher BA, Welsh JD. Individual differences in emotion regulation and behavior problems in preschool children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:518–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Buckhalt JA. Children and violence: The role of children’s regulation in the marital aggression–child adjustment link. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:3–15. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0042-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ, Willoughby MT. Testing main effects and interactions in latent curve analysis. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:220–237. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Edwards MC, Wirth RJ, Hussong AM, Chassin L. The incorporation of categorical measurement models in the analysis of individual growth. In: Little TD, Bovaird JA, Card NA, editors. Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies. New York: Psychology Press; 2007. pp. 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Willoughby MT. Implications of latent trajectory models for the study of developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:581–612. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM. Adrenocortical underpinnings of children’s psychological reactivity to interparental conflict. Child Development. 2008;79:1693–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Cicchetti D, Manning LG, Zale E. Children’s patterns of emotional reactivity to conflict as explanatory mechanisms in links between interpartner aggression and child physiological functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1384–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Geus EJC, Kupper N, Boomsma DI, Sneider H. Bivariate genetic modeling of cardiovascular stress reactivity: Does stress uncover genetic variance? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:356–364. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318049cc2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Development. 1994;65:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Hops H. Analysis of longitudinal data within accelerated longitudinal designs. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Vivian D. Spouses’ reasons for not reporting existing marital aggression as a marital problem. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:443–453. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT. Biological sensitivity to context. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Parental drinking problems and children’s adjustments: Vagal regulation and emotional reactivity as pathways and moderators of risk. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:499–515. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Stability of respiratory sinus arrhythmia in children and young adolescents: A longitudinal examination. Developmental Psychobiology. 2005;46:66–74. doi: 10.1002/dev.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Harger J, Whitson S. Exposure to parental conflict and children’s adjustment and physical health: The moderating role of vagal tone. Child Development. 2001;72:1617–1636. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Hinnant JB, Erath S. Developmental trajectories of delinquency symptoms in childhood: The role of marital conflict and autonomic nervous system activity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:16–32. doi: 10.1037/a0020626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Keller PS, Erath SA. Marital conflict and risk for child maladjustment over time: Skin conductance level reactivity as a vulnerability factor. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:715–727. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Erath S, Cummings EM, Keller P, Staton L. Marital conflict and children’s externalizing Behavior: Interactions between parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system activity. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00501.x. (1, Serial No. 292) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Whitson SA. Longitudinal relations between marital conflict and child adjustment: Vagal regulation as a protective factor. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:30–39. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M, Gunnar MR, Burraston BO. Effects of a therapeutic intervention for foster preschoolers on diurnal cortisol activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:892–905. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galles SJ, Miller A, Cohn JF, Fox NA. Estimating parasympathetic control of heart rate variability: Two approaches to quantifying vagal tone. Psychophysiology. 2002;39 Suppl. 1:S37. [Google Scholar]

- Gentzler AL, Santucci AK, Kovacs M, Fox NA. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity predicts emotion regulation and depressive symptoms in at-risk and control children. Biological Psychology. 2009;82:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF. Children’s emotional reactions to stressful parent-child interactions. Marriage and Family Review. 2002;34:265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Taylor EW. Toward understanding respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Relations to cardiac vagal tone, evolution and biobehavioral functions. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:263–285. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, De I. Parasympathetic regulation and parental socialization of emotion: Biopsychosocial processes of adjustment in preschoolers. Social Development. 2008;17:211–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Nuselovici JN, Utendale WT, Coutya J, McShane KE, Sullivan C. Applying the polyvagal theory to children’s emotion regulation: Social context, socialization, and adjustment. Biological Psychology. 2008;79:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnant JB, Elmore-Staton L, El-Sheikh M. Developmental trajectories of respiratory sinus arrhythmia and pre-ejection period in middle childhood. Developmental Psychobiology. 2011;53:59–68. doi: 10.1002/dev.20487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnant JB, El-Sheikh M. Children’s externalizing and internalizing symptoms over time: The role of individual differences in patterns of RSA responding. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:1049–1061. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. 1975 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;35:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Gottman JM. Vagal tone protects children from marital conflict. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Gottman JM. Buffering children from marital conflict and dissolution. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26:157–171. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2602_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Martin NC, Liu T, Dolbin-MacNab M. Multilevel modeling in the context of family research. In: Sprenkle DH, Pieercy FP, editors. Research methods in family therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 405–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kertes DA, Gunnar MR, Madsen NJ, Long JD. Early deprivation and home basal cortisol levels: A study of internationally adopted children. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:473–491. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibig SD. Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: A review. Biological Psychology. 2010;84:394–421. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper N, Willemsen G, Posthuma D, De Boer D, Boomsma DI, De Geus EJC. A genetic analysis of ambulatory cardiorespiratory coupling. Psychophysiology. 2005;42:202–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachar D, Gruber CP. Personality Inventory for Children: Second edition (PIC-2) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lance CE. Residual centering, exploratory and confirmatory moderator analysis, and decomposition of effects in path models containing interactions. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1988;12:163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Rhoades BL, Nix RL, Greenberg MT The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Modeling the interplay of multilevel risk factors for future academic and behavior problems: A person-centered approach. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:313–335. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Bovaird JA, Widaman KF. On the merits of orthogonalizing powered and product terms: Implications for modeling interactions among latent variables. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2006;13:497–519. [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, Ouellet-Morin I, Hupbach A, Tu MT, Buss C, Walker D, et al. Beyond the stress concept: Allostatic load—A developmental biological and cognitive perspective. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 2. Developmental neuroscience. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh P, Beauchaine TP, Williams B. Dissociation of sad facial expressions and autonomic nervous system responding in boys with disruptive behavior disorders. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:100–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Rakaczky CJ, Stoney CM, Manuck SB. Are cardiovascular responses to behavioral stressors a stable individual difference variable in childhood? Psychophysiology. 1987;24:464–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1987.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Woodall KL, Stoney CM. Changes in and stability of cardiovascular responses to behavioral stress: Results from a four-year longitudinal study of children. Child Development. 1990;61:1134–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Stellar E. Stress and the individual: Mechanisms leading to disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993;153:2093–2102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Wingfield JC. The concept of allostasis in biology and biomedicine. Hormones and behavior. 2003;43:2–15. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(02)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:25–45. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GA. Infants’ and mothers’ vagal reactivity in response to anger. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1392–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]