Abstract

Lymphomas that develop in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected patients are predominantly aggressive B-cells lymphomas. The most common HIV-associated lymphomas include Burkitt lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (that often involves the CNS), primary effusion lymphoma, and plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL). Of these, PBL is relatively uncommon and displays a distinct affinity for presentation in the oral cavity. In this manuscript we report a previously undescribed primary leptomeningeal form of PBL in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. A 40-year-old HIV positive man presented with acute onset confusion, emesis, and altered mental status. Lumbar puncture showed numerous nucleated cells with atypical plasmocyte predominance. CSF flowcytometry showed kappa restriction with CD8 and CD38 positivity and negative lymphocyte markers, while the MRI showed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement. As the extensive systemic work-up failed to reveal any disease outside the brain, an en bloc diagnostic brain and meningeal biopsy was performed. The biopsy specimen showed sheets of plasmacytoid cells with one or more large nuclei, prominent nuclear chromatin, scattered mitoses, and abundant cytoplasm, highly suggestive of plasmablastic lymphoma. HIV-associated malignancies have protean and often confusing presentations, which pose diagnostic difficulties posed to the practicing neurological-surgeons. Even in cases where an infectious cause is suspected for the meningeal enhancement, neoplastic involvement should be considered, and cytology and flow-cytometry should be routinely ordered on the CSF samples.

Keywords: Plasmablastic lymphoma, HIV infection, Leptomeningeal carcinomatoses

Clinical presentation

A 40-year-old HIV positive man presented to the emergency department with acute onset confusion, emesis, and altered mental status. Further history revealed him to be bisexual, and a cocaine user, on chronic highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) therapy. He had a history of an outbreak of herpes zoster a week ago, cryptococcal meningitis causing blindness and deafness 3 years ago, as well as Hepatitis-C, and anal condylomas. He was on chronic Co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole) therapy, as well as acyclovir and fluconazole. At presentation, his temperature was 36.5°C, BP 140/70 mm Hg, and pulse 75/min. The patient was mildly confused and showed mild neck stiffness. Neurologically he was drowsy but easily awakened, and did not follow two-step commands. Fundoscopy showed marked optic atrophy bilaterally. Cranial nerve examination was otherwise within normal limits. Motor exam showed normal strength and tone across all extremities. Sensory examination was within normal limits. His hemoglobin was 11 mg/dl, and white cell count was 5100/mm3. Lumbar puncture showed a protein level of 53 mg/dl, glucose of 49 mg/dl, and 211 nucleated cells/mm3 with atypical plasmacyte predominance. The patient was admitted and managed as an inpatient. CSF flowcytometry showed kappa restriction with CD8 and CD38 positivity and negative lymphocyte markers. CSF cryptococcal antigen was negative although serum cryptococcal antigen was positive at a titre of 64, with no anti-cryptococcal antibody. Serum RPR and CSF VDRL were negative and CSF AFB stain and TB PCR were also negative. The patients CD4 count was found to be 94 and viral load 18,500. Gadolinium enhanced MRI scan showed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement, with enhancing nodules along the lateral aspect of the left cavernous sinus and left temporal pole (Fig. 1). A metastatic work up including cheat, abdomen and pelvis CT as well as a whole body PET scan failed to reveal an underlying solid tumor. An iliac crest bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of plasma cell neoplasia. A right frontal craniotomy was performed for an en bloc diagnostic brain and meningeal biopsy. Intraoperatively the arachnoid was found to be milky and thickened. The biopsy specimen showed sheets of plasmacytoid cells with one or more large nuclei, prominent nuclear chromatin, scattered mitoses, and abundant cytoplasm, with focal extension into underlying brain parenchyma along Virchow-Robin spaces, highly suggestive of plasmablastic lymphoma (Fig. 2). Also were seen scattered nests of encapsulated cryptococci within the leptomeninges and underlying brain parenchyma with no associated inflammatory response. After two additional weeks of anti-fungal therapy for Cryptococcus, intrathecal chemotherapy was begun for his LMM with thiotepa via an Ommaya reservoir.

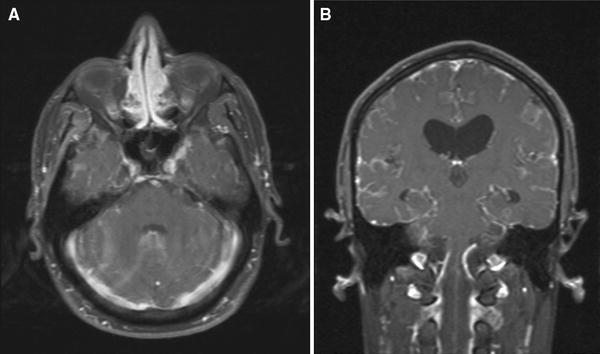

Fig. 1.

Postgadolinium axial fat saturated T1W MR image shows abnormal diffuse enhancement with in the sulcii throughout the brain indicative of a diffuse leptomeningeal process (a). In addition there is focal nodular enhancement adjacent to the left cavernous sinus and along the left sphenoid ridge These nodules could represent granulomas or neoplastic process. Postgadolinium Coronal fat saturated T1W MR image obtained 18 days after images in a shows progression of the diffuse leptomeningeal process with increased hydrocephalus (b)

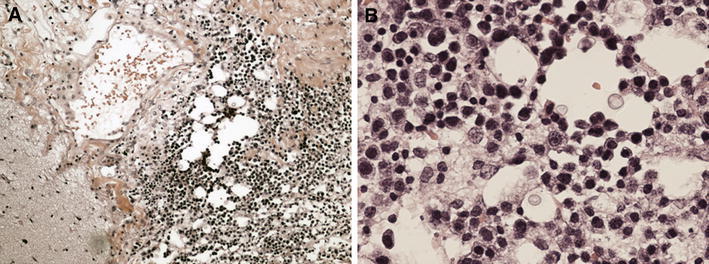

Fig. 2.

Typical morphological features of plasmablastic lymphoma in the meningeal biopsy: sheets of plasmacytoid cells with one or more large nuclei, prominent nuclear chromatin, scattered mitoses, and abundant cytoplasm (a hematoxylin-eosin × 100, b hematoxylin-eosin × 400)

Conclusions

Plasmablastic lymphoma, originally described in 1997 by Delecluse et al. [4] is an aggressive variant of diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma seen predominantly in a setting of AIDS and nearly always in extranodal sites. Subsequently, other cases have been reported, mostly in a setting of AIDS or together with iatrogenic immune suppression or advanced age [1]. Sites outside the oral cavity have been described, including the anorectal region [2], skin [10, 12], lung [11], and breast [16]. One previous report has described the occurrence of a primary central nervous system (CNS) PBL in an AIDS patient as a well-defined, hyperdense, contrast enhancing mass in the right basal ganglia with extensive peritumoral edema and mass effect [13]. Our report is the first to describe the previously unrecognized primary leptomeningeal form of PBL in an AIDS patient. Interestingly this was associated with CNS cyptococcosis suggesting a role for chronic antigen stimulation in its pathogenesis. Such association of NHLs with chronic infection including viral infections (EBV, HHV8) as well as chronic tuberculous pyothorax is known to occur [9].

Lymphomas in HIV patients are heterogenous and reflect several pathogenetic mechanisms such as chronic antigen stimulation, multiple genetic alterations, and cytokine dysregulation. Based on a similar morphology and behavior, plasmablastic lymphoma needs to be distinguished from the immunoblastic variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, classic (body cavity-based) and solid (extracavitary) variants of primary effusion lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma with plasmacytoid differentiation, and extramedullary plasmablastic tumors secondary to multiple myeloma or plasmacytomas. Plasmablastic lymphoma is characterized by immunoblastic morphology and plasma cell phenotype. In other words, plasmablasts are lymphoid cells that morphologically resemble B-cell immunoblasts but have acquired a plasma cell immunophenotype (i.e, loss of B-cell markers and surface immunoglobulin with the acquisition of plasma cell surface markers) [13]. Thus, unlike immunoblasts, plasmablasts fail to express CD45 (leukocyte common antigen) as well as the B-cell marker CD20 and are only variably immunoreactive for CD79a–a broader-spectrum B-cell marker. They are also negative for pan-T-cell markers. Positive staining for plasma cell markers such as VS38c, CD38, MUM-1, and CD138 indicates a phenotype akin to plasma cells [13]. PBL has been etiologically linked to Epstein-Barr virus, Kaposi Sarcoma human virus, and human herpesvirus type-8 infections in addition to HIV [3, 5]. Microscopic examination shows infiltrates of large atypical plasmacytoid cells with abundant cytoplasm, round nuclei, and occasional, centrally located, prominent nucleoli [14]. Several different immunohistochemical markers have been used in an attempt to characterize these lesions [6]. Of these CD 138 is most consistently positive and indicates plasma cell differentiation of the tumor cells [6, 8]. Immunoglobin heavy and light chain restrictions are often present [2, 15]. Ultrastructural features under electron microcopy include round nuclei with clumped heterochromatin and large nucleoli, with concentrically arranged rough endoplasmic reticulum in the cytoplasm [7].

HIV associated PBL has been treated with a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, but the efficacy of treatment is unclear. The previously reported case of CNS PBL was treated with intrathecal methotrexate but the patient was lost to follow up and the outcome is uncertain [15]. Published reports indicate that these are aggressive tumors, frequently resistant to therapy, and often rapidly fatal.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Borenstein J, Pezzella F, Gatter KC. Plasmablastic lymphomas may occur as post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Histopathology. 2007;51:774–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chetty R, Hlatswayo N, Muc R, Sabaratnam R, Gatter K. Plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV+ patients: an expanding spectrum. Histopathology. 2003;42:605–609. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cioc AM, Allen C, Kalmar JR, Suster S, Baiocchi R, Nuovo GJ. Oral plasmablastic lymphomas in AIDS patients are associated with human herpesvirus 8. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:41–46. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, Hummel M, Marafioti T, Schneider U, Huhn D, Schmidt-Westhausen A, Reichart PA, Gross U, Stein H. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deloose ST, Smit LA, Pals FT, Kersten MJ, van Noesel CJ, Pals ST. High incidence of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection in HIV-related solid immunoblastic/plasmablastic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2005;19:851–855. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folk GS, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, Foss RD. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goedhals J, Beukes CA, Cooper S. The ultrastructural features of plasmablastic lymphoma. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:427–433. doi: 10.1080/01913120600854673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gujral S, Shet TM, Kane SV. Morphological spectrum of AIDS-related plasmablastic lymphomas. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:121–124. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.40423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iuchi K, Aozasa K, Yamamoto S, Mori T, Tajima K, Minato K, Mukai K, Komatsu H, Tagaki T, Kobashi Y, et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the pleural cavity developing from long-standing pyothorax. Summary of clinical and pathological findings in thirty-seven cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1989;19(3):249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan LB, Lessells AM, Goodlad JR. Plasmablastic lymphoma arising at a cutaneous site. Histopathology. 2005;46:113–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Y, Rodrigues GD, Turner JF, Vasef MA. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the lung: report of a unique case and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:282–285. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0282-PLOTL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicol I, Boye T, Carsuzaa F, Feier L, Collet Villette AM, Xerri L, Grob JJ, Richard MA. Post-transplant plasmablastic lymphoma of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:889–891. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. Editorial comment: plasmablastic lymphoma–a diagnostic and therapeutic puzzle. AIDS Read. 2007;17:448–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riedel DJ, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhao XF, Redfield RR, Gilliam BL. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity: a rapidly progressive lymphoma associated with HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:261–267. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shuangshoti S, Assanasen T, Lerdlum S, Srikijvilaikul T, Intragumtornchai T, Thorner PS. Primary central nervous system plasmablastic lymphoma in AIDS. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34:245–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Hernandez OJ, Sen F. Plasmablastic lymphoma involving breast: a case diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration and core needle biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:257–261. doi: 10.1002/dc.20784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]