Graphical abstract

A novel bis-phosphaalkenyl based PNP-pincer was prepared and its crystal structure indicates delocalization over the entire π-system including all three donor sites which is also supported by spectroscopic measurements and DFT calculations. The coordination chemistry of the pincer and its precursor have been explored using Cu(I).

Highlights

► A novel bis-phosphaalkenyl based PNP-pincer was prepared. ► The crystal structure indicates delocalization over the entire π-system including all three donor sites. ► DFT calculations and UV–Vis measurements support the interpretation of the structural findings. ► The coordination behavior towards Cu(I) is explored on a preliminary base.

Keywords: Pincer, Phosphaalkene, DFT calculations, Crystal structure

Abstract

Preparation, characterization and structural properties of a novel bis-phosphaalkenyl based PNP-pincer are reported. In this pincer the π-system is delocalized over all three donor sites, which was demonstrated with DFT calculations, UV–Vis measurements and structural findings. As a consequence of this extended delocalization the π-system reveals near coplanarity which is evident from the first crystal structure for an uncomplexed bisphosphaalkenyl PNP-pincer.

1. Introduction

Pincer ligands with a PNP-set of donor centers connected by a central pyridine ring have become a common structural motif for the synthesis of a variety of metal complexes [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Especially for pincers of this type in which the phosphorus atoms are part of a P C double bond, conjugation of the pendant unsaturated units with the central pyridine ring has to be considered [3], [8], [14]. In the course of our investigations dealing with the conjugation of π-spacer-separated bis-σ2λ3-phosphanes [16], [17], [18], we became interested in studying pyridine bridged bisphosphaalkenes for which only a single structurally characterized example was reported in the literature so far [8]. On the other hand, coordination chemistry of low valent and unsaturated phosphanes was widely studied over the last decades [19], [20]. Here we describe synthesis, crystal structure and DFT calculations of a 2,6-bisphosphaalkenyl pyridine in which coplanarity of the ligand based π-systems is observed and for which extended conjugation between the central pyridine ring and the pendant units can be concluded.

2. Results and discussion

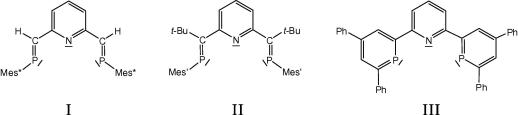

The few phosphaalkenyl based PNP-pincers known so far (Scheme 1) have been synthesized using very different approaches. One way of preparing such compounds is an addition–elimination sequence employing a pyridine based diketone and bulky substituted lithiumsilylphosphanides [3], [8]. For this sequence the specific substitution pattern at the ketone and the phosphanide seem to be essential and for substituent combinations other than in I and II failure of this route has been reported [8]. In an alternative approach the phosphaalkene units are part of a phosphinine rings and the pincer III is obtained using the Märkl route to phosphinines via the corresponding bispyrylium salts [14].

Scheme 1.

Survey of the literature known phosphaalkenyl based PNP-pincers I (Mes∗ = 2,4,6-tri-tert-butylphenyl) [3], II (Mes′ = 2,4-di-tert-butyl-6-methylphenyl) [8] and III[14].

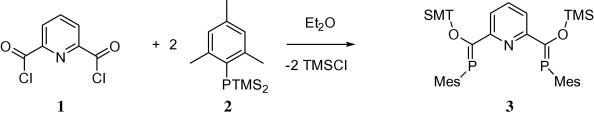

Looking for a more general approach to such pincers, we followed the Becker-route to phosphaalkenes – a strategy which had been successful in our hands for the preparation of 1,1′-ferrocenylene bridged bisphosphaalkenes [16], [17], [18]. Accordingly, the reaction of acid chloride 1 with bissilylphosphane 2 yields the envisaged bisphosphaalkene 3 in a simple one pot reaction (Scheme 2). After removal of the volatile byproducts, 3 can be isolated in pure form by recrystallization.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of pincer 3.

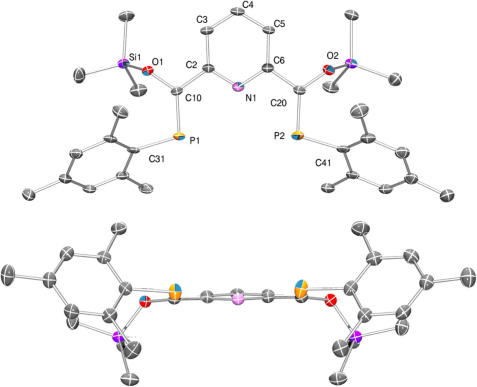

In the 31P NMR spectra of 3 several signals in the expected region for this type of phosphaalkene can be observed (163–172 ppm) owing to the presence of three possible diastereomers EE-, ZZ- and EZ. A pentane solution of 3 was filtered over Celite and concentrated to incipient crystallization. Storage at low temperature (−70 °C) afforded yellow needle shaped crystals. The 31P NMR spectra of these crystals showed a single signal at 165.8 ppm which indicated that only one of the symmetric diastereomers (ZZ) was separated from the isomeric mixture using this procedure. The quality of the crystals obtained this way was suitable for single crystal X-ray diffraction. Compound 3 crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21/c (a = 18.007(2) Å, b = 12.5768(17) Å, c = 14.7045(19) Å, β = 101.180(7)°, V = 3267.0(7) Å3, Z = 4). Details of the structure solution are summarized in Table 1. The crystal structure analysis reveals that both P C units adopt the Z conformation in this isomer (Fig. 1). The distance between the two phosphorus atoms of ca. 4.6 Å should allow concurrent coordination to a metal center as in related PNP pincer systems.

Table 1.

Summary for the acquisition and structure solution of 3.

| Empirical formula | C31H43NO2P2Si2 |

| Formula weight | 579.78 |

| Crystal description | needle, yellow |

| Crystal size | 0.35 × 0.25 × 0.19 mm |

| Crystal system, space group | monoclinic, P21/c |

| Unit cell dimensions | |

| a (Å) | 18.007(2) |

| b (Å) | 12.5768(17) |

| c (Å) | 14.7045(19) |

| β (°) | 101.180(7) |

| V Å(3) | 3267.0(7) |

| Z | 4 |

| Calculated density (Mg/m3) | 1.179 |

| F(0 0 0) | 1240 |

| Linear absorption coefficient μ (mm−1) | 0.234 |

| Absorption correction | semi-empirical from equivalents |

| Maximum and minimum transmission | 0.956 and 0.886 |

| Unit cell determination | 2.31° < Θ < 25.99° |

| 9641 reflections used at 100 K | |

| T (K) | 100 |

| Diffractometer | Bruker APEX-II CCD |

| Radiation source | sealed tube |

| Radiation and wavelength | Mo Kα, 0.71073 Å |

| Monochromator | graphite |

| Scan type | and ω scans |

| Θ Range for data collection (°) | 2.15–26.00 |

| Index ranges | −22 ⩽ h ⩽ 22, −15 ⩽ k ⩽ 15, −16 ⩽ l ⩽ 18 |

| Reflections collected/unique | 28 091/6221 |

| Significant unique reflections | 4954 with I > 2σ(I) |

| R(int), R(sigma) | 0.0524, 0.0506 |

| Completeness to Θ = 26.0° | 96.9% |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| Data/parameters/restraints | 6221/369/0 |

| Goodness-of-fit (GOF) on F2 | 1.049 |

| Final R indices [I > 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0630, wR2 = 0.1685 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0780, wR2 = 0.1872 |

| Extinction expression | None |

| Weighting scheme | |

| Weighting scheme parameters a, b | 0.1265, 1.5250 |

| Largest Δσ in last cycle | 0.001 |

| Largest difference peak and hole (e/Å3) | 1.033 and −0.719 |

| Structure Solution Program | shelxs-97 [23] |

| Structure Refinement Program | shelxl-97 [23] |

Fig. 1.

ORTEP plot of 3 (ellipsoids at 50% probability). Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Top: view along the (0 1 0)-axis with numbering. Bottom: View along the (0 0 1) axis.

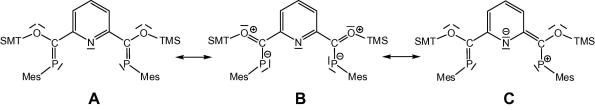

The most noteworthy feature of the molecular structure of 3 is the near coplanarity of the two phosphaalkene units with the central pyridine ring (12.7(2)° and 13.3(3)°). This is in marked contrast to the only other uncomplexed pyridylbisphosphaalkene which has been structurally characterized, i.e. II (Scheme 1), in which the P C units are twisted by as much as 63° [8]. This significant twisting limits the electronic interaction between the P C units and the central aromatic ring so that no conjugation can be expected for II. By contrast in 3 substantial π-conjugation is obvious which involves the electron rich OPC-allylic system and the pyridine core as illustrated by the Lewis resonance structures in Scheme 3. This interpretation is further supported by the increased P C bond distances in 3 (1.701(3) Å, 1.702(3) Å) compared to the more isolated P C bond in II (1.674(4) Å). By contrast the (aryl)C–C(P-alkene) distances are very similar for 3 (1.484(3) and 1.485(4) Å) and III (1.48 Å).

Scheme 3.

Resonance structures of 3.

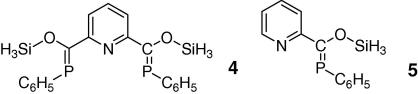

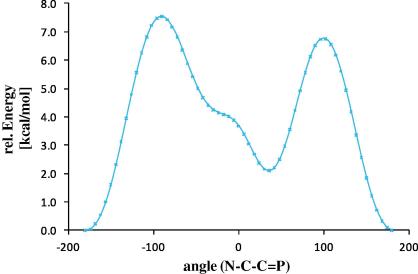

In agreement with a fully delocalized π-system, compound 3 shows an intense yellow color while its twisted analog II was described as colorless. The absorption can be attributed to a π–π∗ transition. To firmly assess the extent of conjugation in 3, quantum mechanical calculations have been performed at the DFT and TD-DFT B3LYP/6-311G∗∗ level of theory on two model systems 4 and 5 (Scheme 4). The CH3 groups have been omitted in the model compounds and were replaced by hydrogen atoms to avoid rotational degrees of freedom. Model compounds are fully optimized. Furthermore a rigid scan on the PES for the dihedral angle around the N–C–C P bond for model compound 5 was performed, which shows the influence of the conjugation of the two π-systems (Fig. 2). Two local minima are observed one with a dihedral angle of −180° and around 34°, for the latter being ca. 2.1 kcal/mol higher in energy. These minima are separated by two barriers for which N–C–C P equals −90° (+7.5 kcal/mol) and +96° (+6.7 kcal/mol). For these two orientations of the pyridine fragment no conjugation of the two π systems should be possible, indicating a stabilization of 6–8 kcal/mol which can be attributed to the effective conjugation of the extended π systems. Hence the total stabilization energy in ZZ-3 is expected to be in the range of 12–16 kcal/mol. In agreement with this no isomerization of ZZ-3 has been observed in solution over several days using 31P NMR.

Scheme 4.

Model compounds 4 and 5 used for ab initio calculations.

Fig. 2.

Energy diagram of the rigid PES scan around the dihedral angle N–C–C P in model compound 5. Relative energies are given in [kcal/mol].

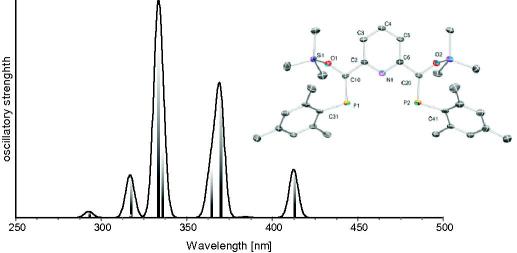

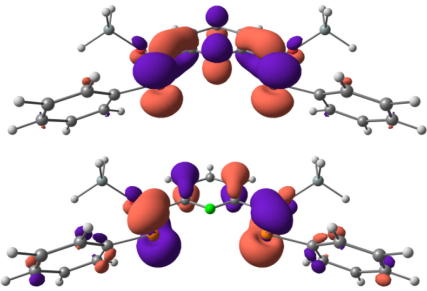

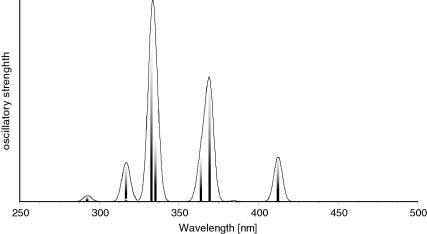

Structural parameters for model compound 4 and the X-ray diffraction data of 3 agree very well (i.e. P C calc. 1.714 Å versus X-ray 1.701(3) and 1.702(3) Å or Cpyr–C: 1.484 Å versus 1.484(3) and 1.485(4) Å). The computed dihedral angles N–C–C P in the model compounds (11.5(3)° and −12.8(3)°) deviate less than 2° from the X-ray data . Analysis of the molecular orbitals gives an insight into the nature of the conjugated system (Fig. 3). The highest molecular orbital (HOMO) shows essential contributions from the π-orbitals of the P C double bonds as well as from the π-system of the central pyridine ring, whereas the LUMO is composed of π∗ orbitals of the P C double bond and antibonding orbitals of the pyridine fragment, which is line with the observed color of compound 3. Furthermore the TD–DFT calculations confirm the energetically lowest band in the UV–Vis to be a π–π∗ transition of the extended conjugated system (Fig. 4). Mulliken and NBO charge analyses yield positively charged phosphorus centers (+0.43 and +0.63) as well as a negatively charged nitrogen atom (−0.36 and −0.45), which is in agreement with a significant contribution of resonance structure C (Scheme 3) also underlined by the slightly elongated P C double bond.

Fig. 3.

Highest occupied (HOMO, bottom) and lowest unoccupied (LUMO, top) molecular orbital of model compound 4 from B3LYP/6-311G∗∗ calculations plotted with the ChemCraft program [http://www.chemcraftprog.com] at an isolevel of 0.04 a.u.

Fig. 4.

UV–Vis transitions in 4 based on TD–DFT calculations (B3LYP/6-311G∗∗).

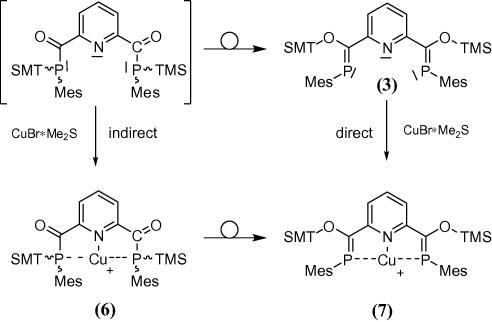

In order to explore the coordination properties of 3 we investigated its behavior towards Cu(I) halides as in related cases [14], [15]. Direct addition of CuBr·Me2S to the isomeric mixture of 3 indicates the formation of different phosphorus containing species as shown by 31P NMR spectroscopy. Based on NMR also the direct complexation of the ZZ isomer of 3 is feasible but has little synthetic use owing to the tedious separation procedure via crystal picking. To get around the likewise complexation of different E/Z isomers of 3 we considered attaching the metal to the corresponding acylphosphane (Scheme 5), which is initially formed below −35 °C in the synthesis of 3 but not isolated. The metal coordinated acylphosphane 6 should then be prone to conversion into the corresponding bisphosphaalkene 7 by twofold silyl migration. We anticipated that via this indirect route the (ZZ) isomer of the bis-phosphaalkene complex could form preferentially. Slow warming to ambient temperature of the thus prepared reaction mixture is accompanied with a significant color change. The dark red color of the reaction mixture is in contrast to the yellow color of uncomplexed 3 and indicates significant interaction with the copper ion. 31P NMR spectroscopic investigations of the reaction mixture indicate successful silyl migration and formation of the P C moiety associated with a coordination shift towards higher field of ca. 15 ppm. Interestingly, employing this indirect route the relative amount of complexed Z,Z isomer 7 (δ(31P) = + 148 ppm) is significantly increased compared with the direct complexation method. This indicates that the coordination sphere of a metal provides some control over the E/Z ratio of the phosphaalkene via acylphosphane rearrangement. As our exploratory results show, direct complexation of bis-phosphaalkene 3 seems to be inferior to indirect complexation via its precursor, at least in the case of Cu(I).

Scheme 5.

Direct and indirect complexation of 3.

3. Conclusion

In summary, we report the preparation, characterization and structural properties of a novel phosphaalkenyl based PNP-pincer with a delocalized π-system. The delocalization over all three donor sites was demonstrated based on DFT calculations, UV–Vis measurements and structural findings. As a consequence of this extended delocalization the π-system reveals near coplanarity which is evident from the first crystal structure for an uncomplexed bisphosphaalkenyl PNP-pincer. This planarity is quite remarkable and even for complexes of related phosphaalkenyl based PNP-pincer ligands the coplanarity of the ligand based π-systems is not necessarily observed. In the Cu(I) complex of III for instance where the P C units are part of phosphinine rings the inter-planar angles range between 25.5° and 31.4° [14]. The relevance of the herein presented pincer system 3 may arise from its potential as an interface between extended π-conjugated strands and metal centers which we intend to explore in the future.

4. Experimental

All reactions were carried out under dry argon atmosphere with standard Schlenk techniques. Solvents were dried with a PureSolve system and degassed prior to use. Mes-PTMS2 [21] and 2,6-bis(chlorocarbonyl)pyridine [22] were prepared according to published procedures. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich or ABCR and used as received.

4.1. Synthesis of 3

Mes-P(TMS)2 (2) (408 mg, 1.37 mmol) is added to a cooled (−70 °C) suspension of 2,6-bis(chlorocarbonyl)pyridine (144 mg, 0.71 mmol) in toluene (20 ml). The resulting mixture is allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred overnight. All volatiles are removed in vacuum and the residue is extracted with pentane and filtered over Celite. Upon concentration to ca. 5 ml the ZZ-isomer of bisphosphaalkene 3 can be precipitated by prolonged cooling to −70 °C as yellow crystalline material (172 mg, 41%). m.p. (pentane) 282–284 °C.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): −0.09 (s, O-TMS, 18H), 2.29 (s, p-Me, 6H), 2.42 (s, o-Me 12H), 6.89 (s, Mes-H, 4H), 7.60 (t, 3JHH 7.8 Hz, Pyr–H, 1H), 7.75 (dt, 3JHH 7.8 Hz, 1.8 Hz, Pyr–H 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 0.23 (s, O-TMS), 21.05 (s, p-Me), 22.20 (d, 8.7 Hz, o-Me), 119.23 (dd, 17.5 Hz, 5.3 Hz), 128.19 (s, 3′-Mes), 133.73 (d, 37.9 Hz, 1′-Mes), 136.29 (s, Pyr), 138.20 (s, 4′-Mes), 141.83 (d, 6.7 Hz, 2′-Mes), 157.88 (d, 29.6 Hz, Pyr), 195.02 (d, 54.9 Hz, P C). 31P NMR (CDCl3, 162 MHz): 165.8 (br. s.). UV–Vis (pentane) , 370 nm, 385 nm (sh), 435 nm (br.), In the crude reaction mixture further 31P NMR signals can be observed (172.3, 170.4, 165.8 (ZZ), 162.9, 162.7) which can be attributed to isomeric phosphaalkene units.

4.2. Attempted synthesis of 6

Mes-P(TMS)2 (2) (154 mg, 0.52 mmol) is added to a cooled (−70 °C) suspension of 2,6-bis(chlorocarbonyl)pyridine (54 mg, 0.26 mmol) in toluene (20 ml). The resulting mixture is allowed to warm to −35 °C and an excess of CuBr∗Me2S (82 mg, 0.40 mmol) is added and stirred for 1 h at this temperature. Stirring is continued overnight warming the reaction mixture to ambient conditions. 31P-Spectroscopic investigation of the crude reaction mixture reveal the presence of broad signals around 150 ppm (152.4, 148.7, 148.2 (presumably ZZ isomer)). All volatiles are removed in vacuum and the residue is extracted with diethyl ether leads to an inseparable mixture of isomeric compounds.

4.3. Computational details

Calculations were carried out with the Gaussian Inc. program package (G03 Rev. B.04). Model systems have been investigated at the B3LYP/6-311G∗∗ level of theory and were fully optimized and were determined as true minima by inspection of their harmonic frequencies having no imaginary frequency. The rigid PES scan on model compound 5 was carried out on a fully optimized system with fixed parameters (in z-matrix format) except for the dihedral angle N–C–C P.

4.4. Crystal structure solution of compound (3)

All measurements were performed using graphite-monochromatized Mo Kα radiation at 100 K. The structure was solved by direct methods (shelxs-97) and refined by full-matrix least-squares techniques against F2 (shelxl-97). The non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters without any constraints. The H atoms of the phenyl rings were put at the external bisector of the C–C–C angle at a C–H distance of 0.95 Å and a common isotropic displacement parameter was refined for the H atoms of the central phenyl ring as well as for those of the phenyl rings of the mesityl groups. The H atoms of the methyl groups were refined with common isotropic displacement parameters for the H atoms of the same group and idealized geometry with tetrahedral angles, enabling rotation around the X–C bond, and C–H distances of 0.98 Å. Further details are summarized in Table 1.

Acknowledgment

The authors A.O. and R.P. would like to thank the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) for financial support (Grants P18591-B03 and P20575-N19).

Footnotes

CCDC 806606 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for 3. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ica.2011.02.078.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

References

- 1.Dahlhoff W.V., Nelson S.M. J. Chem. Soc. A. 1971:2184. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacco A., Vasapollo G., Nobile C.F., Piergiovanni A., Pellinghelli M.A., Lanfranchi M. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988;356:397. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jouaiti A., Geoffroy M., Bernardinelli G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:5071. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawatsura M., Hartwig J.F. Organometallics. 2001;20:1960. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekici S., Gudat D., Nieger M., Nyulaszi L., Niecke E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:3367. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3367::AID-ANIE3367>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hahn C., Cucciolito M., Vitagliano A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9038. doi: 10.1021/ja0263386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hermann D., Gandelman M., Rozenberg H., Shimon L.J.W., Milstein D. Organometallics. 2002;21:812. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ionkin A.S., Marshall W.J. Heteroatom Chem. 2002;13:662. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trovitch R.J., Lobkovsky E., Chirik P.J. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:7252. doi: 10.1021/ic0608647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feller M., Ben-Ari E., Gupta T., Shimon L.J.W., Leitus G., Diskin-Posner Y., Weiner L., Milstein D. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:10479. doi: 10.1021/ic701044b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi A., Okazaki M., Ozawa F., Tanaka R. Organometallics. 2007;26:5246. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kloek S.M., Heinekey D.M., Goldberg K.I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:4736. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cochran B.M., Michael F.E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2786. doi: 10.1021/ja0734997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller C., Pidko E.A., Lutz M., Spek A.L., Vogt D. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:8803. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Vlugt J.I., Pidko E.A., Vogt D., Lutz M., Spek A.L., Meetsma A. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:4442. doi: 10.1021/ic800298a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser C., Nieger M., Pietschnig R. Organometallics. 2006;25:2667. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser C., Orthaber A., Nieger M., Belaj F., Pietschnig R. Dalton Trans. 2006;32:3879. doi: 10.1039/b604501d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moser C., Belaj F., Pietschnig R. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:12589. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathey F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:1578. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Floch P.L. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006;250:627. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker G., Mundt O., Roessler M., Schneider E. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1978;443:42. [Google Scholar]

- 22.An B.-L., Shi J.-X., Wong W.-K., Cheah K.-W., Li R.-H., Yang Y.-S., Gong M.-L. J. Lumin. 2002;99:155. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheldrick G. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008;A64:112. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.