Abstract

Background

Evidence from the literature suggests that substance abuse, violence, HIV risk, depressive symptoms, and underlying socioeconomic conditions are tied intrinsically to health disparities among Latinas. Although these health and social conditions appear to comprise a syndemic, an underlying phenomenon disproportionately accounting for the burden of disease among marginalized groups, these hypothesized relationships have not been formally tested.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess (a) if substance abuse, violence, HIV risk, and depressive symptoms comprised a syndemic and (b) if this syndemic was related to socioeconomic disadvantage among Latinas.

Methods

Baseline assessment data from a randomized controlled community trial testing the efficacy of an HIV risk reduction program for adult Latinas (n = 548) were used to measure demographic variables, substance abuse, violence, risk for HIV, and depressive symptoms. Structural equation modeling was used to test a single underlying syndemic factor model and any relation to socioeconomic disadvantage.

Results

The results of this study support the idea that HIV risk, substance abuse, violence, and depressive symptoms comprise a syndemic, χ2(27) = 53.26, p < .01 (relative χ2 = 1.97, comparative fit index = .91, root mean square error of approximation = .04). In addition, in limited accord with theory, this factor was related to 2 measures of socioeconomic disadvantage, percentage of years in the United States (b = 7.55, SE = 1.53, p < .001) and education (b = −1.98, SE = .87, p < .05).

Discussion

The results of this study could be used to guide public health programs and policies targeting behavioral health disparity conditions among Latinos and other vulnerable populations. Further study of the influence of gender-role expectations and community-level socioeconomic indicators may provide additional insight into this syndemic.

Keywords: HIV, substance-related disorders, violence

The major goals of Healthy People 2010 include the elimination of health disparities, especially those relating to substance abuse, violence, HIV, andmental health—4 of the 10 leading health indicators (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [DHHS], 2000). As the goals and objectives for Healthy People 2020 are discussed, health equity and behavioral and mental health conditions continue to take priority (DHHS, 2009a). Central to improving the health of all citizens is the continued expansion of understanding how and why certain health conditions disproportionately affect populations experiencing health disparities. An increased understanding of health disparities will assist in the creation of innovative and comprehensive solutions to the complex health problems experienced by high-risk groups. Nurses are being called upon increasingly to lead in the creation of these efforts in preparation for a reformed healthcare system, one to promote wellness and address the complex and diverse needs of the 21st century (Institute of Medicine, 2010).

Syndemic theory is receiving attention from public health professionals and health and social scientists as a new way of conceptualizing and addressing health disparities (González-Guarda, 2009). The syndemic orientation to community and public health considers clustering health conditions and their synergistic effects on morbidity and mortality, and the development of interventions addressing the underlying social-environmental issues linking these conditions (Millstein, 2008; Singer, 2009). Substance abuse, violence, HIV infection, and mental health conditions such as depressive symptoms have been identified as a specific type of syndemic disproportionately affecting the health and well-being of marginalized groups (Romero-Daza, Weeks, & Singer, 2003; Singer, 1996). Although evidence from both qualitative and quantitative studies suggest that these conditions may represent an underlying phenomenon (González-Guarda, Peragallo, Urrutia, Vasquez, & Mitrani, 2008; Romero-Daza et al., 2003), syndemic theory has never been applied and tested formally to the understanding of these conditions.

The purposes of this study were to test whether variations in substance abuse, violence, HIV risk, and depressive symptoms may be reduced to a single underlying syndemic factor and to explore if this syndemic is related to socioeconomic disadvantage in a sample of Latinas in the United States.

Syndemic Model for Latinas

The syndemic model for substance abuse, violence, risk for HIV infection, and mental health among Hispanics (henceforth referred to as the Syndemic Model for Hispanics; González-Guarda, Florom-Smith, & Thomas, in press) was used to conceptualize the relationships among the major study variables in Latinas. According to the Syndemic Model for Hispanics, substance abuse, violence, risk for HIV, and depressive symptoms can be conceptualized as a syndemic—interconnected, inseparable health issues that interact to account for health disparities among Hispanics disproportionately (Singer, 1996). Differing from traditional concepts of comorbidity or co-occurring epidemics, in a syndemic, two or more health issues interact within the context of poor physical and social conditions to increase the burden of disease among marginalized groups (Singer, 2009).

In the first syndemic identified by Singer (1996, 2009), the Substance Abuse, Violence, and AIDS (SAVA) syndemic, the links between these conditions among inner-city Hartford, Connecticut, residents were described as so interrelated they were inseparable. The connections between the SAVA conditions and the social context within which these linked problems exist are essential to understanding why some health issues disproportionately affect vulnerable populations (Millstein, 2008).

According to the Syndemic Model for Hispanics and syndemic theory, syndemics such as SAVA not only exist among communities experiencing disadvantageous socioeconomic conditions (e.g., unemployment, poverty, family instability, decreased access to healthcare, discrimination) but are also caused by these conditions (Singer, 1996, 2009). The Syndemic Model for Hispanics provides a framework for understanding these synergistic relationships by placing the syndemic conditions substance abuse, HIV/AIDS, violence, and mental health as mutually interacting, influential core issues that contribute to health disparities among Hispanics. In addition to these core syndemic conditions, the Syndemic Model for Hispanics includes individual factors (intrinsic factors such as self-esteem and extrinsic factors such as employment, income, and education), relationship factors (e.g., relationship or family conflict, communication), socioenvironmental factors (e.g., discrimination, structural unemployment, underemployment), and cultural factors (e.g., traditional gender norms, acculturation) that serve as common risk and protective factors. As conceptualized in the Syndemic Model for Hispanics, each of these factors is a potential connection between the syndemic conditions (González-Guarda et al., in press).

Literature Review

The Syndemic Among Latinas

Studies conducted with Latinas have begun to delineate the links between substance abuse, intimate partner violence (IPV), and risk for HIV and depressive symptoms. Latinas living with HIV and experiencing trauma have been found to engage in greater drug use and to have higher levels of depressive symptoms than do women with either of these conditions singly (Newcomb & Carmona, 2004). Similarly, Latinas who experienced more childhood conflict such as physical or emotional abuse were found more likely to report increased drug use, more psychological distress, more pregnancies, and a higher number of sexual partners than were adolescents reporting no childhood conflict (Newcomb, Locke, & Goodyear, 2003). In addition, Latinas using drugs themselves were found more likely to report substance-using partners who perpetrated violence and engaged in high-risk sexual behavior (González-Guarda et al., 2008). It has been proposed that the syndemic conditions are related through underlying risk and protective factors that connect these (i.e., confounders). For example, among some Latinas, condom use may not be related to substance use or to IPV directly but rather indirectly through gender-role expectations, partner’s high-risk sexual behaviors, and cultural and relationship factors that link the syndemic conditions (Cianelli, Ferrer, & McElmurry, 2008; Hader, Smith, Moore, & Holmberg, 2001; Peragallo, 1996; Raj, Silverman, & Amaro, 2004).

Socioeconomic Disadvantage and the Syndemic

Social and economic disadvantages appear to increase Latinas’ risk for substance abuse, IPV, risky sexual behaviors, and depressive symptoms when conceptualized as distinct health conditions or comorbidities (Caetano & Cunradi, 2003; Caetano, Cunradi, Clark, & Schafer, 2000; Jasinski, Asdigian, & Kaufman Kantor, 1997; Rhodes et al., 2007). Evidence of the close relationship between these socioeconomic factors and the syndemic conditions suggest that this phenomenon may be better conceptualized as a syndemic among Latinas (González-Guarda et al., 2008). For example, the level of depressive symptoms, risk for IPV, and unmet mental health needs have all been found to be related inversely to education, income, and employment among Latinas (Heilemann, Lee, & Kury, 2002; Lipsky & Caetano, 2007). Furthermore, adverse socioeconomic conditions such as inadequate financial resources or unemployment may lead to a greater likelihood of contracting HIV among Latinas, even when a history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is also considered (Wyatt et al., 2002). It appears that socioeconomic disadvantage such as poverty and immigrant status may contribute to HIV acquisition because Latinas have fewer resources to leave abusive partners that place them at risk (Moreno, 2007).

The length of time Latinas spend in the United States may be another demographic factor associated with the syndemic. Generally speaking, the longer Latinos live in the United States and adapt to a new culture and environment, the more negative health behaviors they demonstrate (Vega, Rodriguez, & Gruskin, 2009). However, few researchers have explored these relationships solely among Latinas while considering other related socioeconomic factors (e.g., income, education). Investigators conducting research with other groups of Latinos, such as adolescents, men who have sex with men, and couples, have found that the more time Latinos live in or acculturate to the United States, the more likely they are to encounter stress, family conflict, social isolation, high-risk sexual behaviors, substance abuse, and mental health problems (Buchanan & Smokowski, 2009; Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano Vaeth, & Harris, 2007; De Santis, Colin, Vasquez, & McCain, 2008).

However, the same may not apply for Hispanic women, as time spent in the United States has been associated with higher levels of education and greater condom use (Abel & Chambers, 2004). Consequently, more research is needed to clarify the relationship between socioeconomic disadvantage and health disparities among Latinas. Applying the Syndemic Model to the understanding of how substance abuse, violence, HIV risk, and depressive symptoms impact Latinas, the following research hypotheses were tested: (a) Substance abuse, violence, risk for HIV, and depressive symptoms can be reduced to a single latent variable (i.e., a syndemic factor); and (b) the syndemic factor is related to socioeconomic disadvantage.

Methods

Design

Baseline data from a randomized control trial of SEPA(Salud, Educación, Prevención y Autocuidado [Health, Education, Prevention & Self-care]), a culturally specific intervention designed for Latinas in the United States to reduce HIV risk, were used for this study (n = 548). In SEPA, five 2-hour group participatory and skill-building sessions that cover HIV/AIDS in the Hispanic community, STIs, HIV/AIDS prevention (e.g., condom use), negotiation and communication with the partner, IPV, and substance abuse are conducted. Cross-sectional assessments, including standardized health and behavior measures, were administered to participants via face-to-face interviews conducted by bilingual female study personnel in the participant’s language preference (i.e., English or Spanish). Baseline data were collected between January 2008 and April 2009.

Sample and Setting

This trial included a sample of Latina women from South Florida between the ages of 18 and 50 years reporting sexual activity in the past 3 months upon initial eligibility screening. Participants were recruited from community-based settings. A large percentage of the initial sample was recruited from a community-based organization (CBO) providing social services (e.g., English classes, child care, job development and placement, health education) to Latinos and immigrants. Study personnel posted flyers and made presentations at this CBO and other community-based settings (e.g., libraries, community clinics, churches) to inform potential candidates about the study. Participants were informed that the primary aim of the study was to evaluate an HIV prevention program for Latinas. Study participants were encouraged to tell family and friends about the study (i.e., snowball sampling). Assessments were conducted at the CBO, and a nearby study office was rented once study enrollment increased.

Procedures

University of Miami Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before recruitment. Participants were recruited through (a) a community-based social service (e.g., English classes, child care, job development and placement, health education) organization for Hispanics, (b) an urban Florida Department of Health site, (c) flyers posted in the community, and (d) public service messages delivered via mass media. Candidates interested in participating in SEPA either (a) gave their names and telephone numbers to study personnel and were called by the centralized scheduler for eligibility screening or (b) were given a flyer or business card containing the study telephone number. If eligible, candidates were scheduled for the assessment. Upon meeting with the candidates, assessors described the study procedures, answered participants’ questions, obtained informed consent, and completed the baseline assessment. Assessments were collected using a research management software system (Velos, Fremont, CA), allowing assessors to ask participants questions and document responses on the computer. Baseline assessments took approximately 3 hours to complete. Participants received a monetary incentive of $50 upon the completion of the assessment to compensate for their time, travel, and child care costs.

Intervention

As an HIV prevention intervention for Hispanic women (Peragallo et al., 2005), SEPA is guided by a conceptual framework integrating the social cognitive model of behavioral change (Bandura, 1977) for the content and activities of the intervention and Friere’s (1970) pedagogy for the delivery andAQ1 contextual tailoring of the intervention. The intervention consists of five 2-hour sessions delivered in small groups with an average of 8 to 10 women. The sessions covered HIV and AIDS in the Hispanic community, STIs, prevention of HIV and AIDS (e.g., condom use), negotiation and communication with the partner, IPV, and substance abuse through participatory sessions and skill-building activities.

Measures and Variables

All the measures used in this study were available in English and Spanish. For the measures in which Spanish versions were not available prior to this study, the translation, back-translation, and verification procedure was conducted. These measures were piloted also with a similar group of Hispanic women in South Florida prior to use in this study (González-Guarda et al., 2008).

Socioeconomic Disadvantage

Demographic information was collected at the beginning of the assessments through administration of a standardized form specifically designed for studies at the research center in which this study was housed (e.g., country of origin, years living in the United States, income, health insurance status). Socioeconomic disadvantage was assessed from these demographic variables and included four separate measures: poverty, education, employment, and percentage of years living in the United States. A dummy-coded variable representing poverty status was created using monthly family income for the number of individuals living from that income based on U.S. government guidelines (DHHS, 2009b), with 1 = living in poverty and 0 = living above the poverty line. Dummy-coded variables were created for education (1 = at least a high school education, 0 = less than a high school education) and employment (1 = employed, 0 = unemployed). Percentage of years lived in the United States was calculated by dividing the number of years the participant reported living in the United States by age.

Substance Abuse

An adapted form of the nine-item substance abuse behavior questionnaire (Kelly et al., 1994) was administered. For this study, a scale was created with three items: frequency of alcohol and illicit drug use (two questions) and being drunk or high before sex (one question) in the past 3 months. This subscale showed good reliability (Cronbach’s α = .77). Due to extreme positive skew, this variable was coded as 0 (never on all items) and 1 (endorsing any item such as participants reporting they were drunk before sex at least once in the past 3 months) for analysis.

Violence

Three variables were used to measure exposure to violence: lifetime exposure to abuse, community violence, and partner violence. Data on lifetime exposure to abuse and community violence were collected using the Violence Assessment, developed for a previous HIV risk reduction efficacy trial of SEPA (Peragallo et al., 2005) and adapted in a subsequent pilot study (González-Guarda et al., 2008). The lifetime exposure to abuse scale summed six items of participant reports of ever having been physically, sexually, or psychologically abused during childhood (before the age of 18 years) and during adulthood by someone other than a romantic partner. This subscale had good reliability (Cronbach’s α = .74). Community violence (one item) asked participants to report if they had ever lost a close friend or relative to a violent death (i.e., suicide, homicide, or substance-abuse-related accident; 1 = yes, 0 = no). Partner violence was ascertained with the partner-to-you (victimization) 10-item subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics scales (Strauss & Douglas, 2004), one of the most widely used instrument to measure IPV. The IPV subscale showed strong reliability (Cronbach’s α = .86).

Risk for HIV

Three variables were used to measure risk for HIV: consistent condom use, partner’s risk for HIV, and STI history. The Partner Table, which gathered information regarding the characteristics (e.g., demographics) and sexual behaviors of the participants’ past five intimate relationships (González-Guarda et al., 2008), was used to capture consistent condom use and most recent partner’s risk for HIV. Participants reported frequency of condom use during vaginal sex with their most recent partner. Consistent condom used was defined as reporting always using condoms during vaginal sex (1 = always, 0 = sometimes or never). Partner risk was assessed using six items asking participants to report whether their partner was ever drunk or high (during and not during sexual intercourse, four items); ever injected drugs (one item); and had sex with IV drug users, men, or commercial sex workers (three items). This scale had good reliability (Cronbach’s α =.78). In addition, a health and sexual history was taken in which participants were asked their lifetime exposure to a list of STIs. Participants reporting diagnoses of one or more STIs in their lifetimes were coded as having a positive history of an STI (1 = positive, 0 = negative).

Depressive Symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was administered to assess depressive symptoms. This scale consists of 20 questions asking participants to report the frequency (i.e., number of days in the past week) of experiencing depressive symptoms (e.g., not being to shake off the blues, having a hard time concentrating). Responses to these questions are summed for a total score ranging from 0 to 40 points. Although this scale was used as a continuous measure, scores of 16 and above indicate a likelihood of clinical depression. This scale is used widely in population-based and community studies and has been translated and validated in Spanish (Roberts, 1980). The CES-D showed very good reliability (Cronbach’s α = .94).

Analysis

The primary hypothesis was tested in two stages using Mplus 5.21 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). Full information maximum likelihood estimation allowed the inclusion of all participants, regardless of missing data. Mplus also allowed for modeling with categorical indicators, in this case four dichotomous items, by estimating the probability of observing the categories (a nonlinear function) using a robust weighted least squares estimator. In Stage 1, confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the a priori theory that substance abuse, violence, risk for HIV, and depressive symptoms are aspects of a single underlying phenomena (i.e., a syndemic factor). Model fit was evaluated using three fit indexes: the relative chi-square test, comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The relative chisquare test (e.g., Kline, 1998) adjusts for the effects of sample size on the chi-square test and equals the chi-square value divided by the degrees of freedom, with values less than 3 indicating a good fit. The CFI (Bentler, 1990) ranges from 0 to 1, with values ≥.90 indicating a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For the RMSEA (Hu & Bentler, 1999), values ≤.06 indicate a good fit. In Stage 2, the initial model was revised to improve model fit by removing items with nonsignificant loadings and correlating errors based on modification indexes. A follow-up analysis was performed to provide some evidence of validity. This follow-up analysis examined whether, as expected by theory, the syndemic factor was related to socioeconomic disadvantage.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Descriptive information regarding the sample and the variables included in the analysis is presented in Table 1. The sample T1 consisted of adult women (M = 38.48 years of age, SD = 8.53 years), the majority of whom completed at least a high school education (74%), were unemployed (67%), lived in poverty (56%), and lived in the United States for more than 10 years (M = 11.41 years, SD = 10.33 years). The majority of participants scored over the clinical cutoff point for depressive symptoms (M = 16.41, SD = 12.91) and reported at least one incident of physical, sexual, or psychological abuse in their lifetime (M = 1.07, SD = 1.49). Over a quarter of women reported experiencing community violence (26%) and 13% reported being high or drunk in the past 3 months. Although reported lifetime history of having an STI was low (7%), few participants consistently used condoms (15%).

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics and Syndemic Indicators (n = 548)

| Variables | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.48 | 8.53 |

| Years in the United States | 11.41 | 10.33 |

| Years of education | 13.37 | 3.45 |

| Number of children | 1.61 | 1.36 |

| Depressive symptoms | 16.41 | 12.91 |

| Partner violence | 0.39 | 0.52 |

| Lifetime abuse | 1.07 | 1.49 |

| Partner risk | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| Variables | n | % |

| High school education | 404 | 74 |

| Employed | 180 | 33 |

| Family size and income (poverty) | ||

| 2 or fewer people (<$1,000/month) | 93 | 17 |

| 3–6 people (<$2,000/month) | 207 | 38 |

| 7 or greater people (<$3,000/month) | 5 | 1 |

| Experienced community violence | 140 | 26 |

| Positive STI history (lifetime) | 37 | 7 |

| Consistent condom use | 84 | 15 |

| Any substance use (past 3 months) | 70 | 13 |

Note. Frequency (%) for positive answers shown for dichotomous variables. STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Hypothesis Testing

Three variables, partner violence, lifetime abuse, and partner risk, were positively skewed. Therefore, a square root transformation was used for analysis. This transformation effectively reduced the skewness and kurtosis of these variables. Depressive symptoms were approximately normally distributed and the remaining four variables (community violence, STI history, consistent condom use, and substance use) were dichotomous. The Stage 1 model with a single latent factor showed an unacceptable fit to the data, χ2(16) = 51.81, p < .001 (relative χ2 = 3.24, CFI = .85, RMSEA = .06; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Unstandardized Loadings for Indicators of the Syndemic Factor From Confirmatory Factor Analyses (n = 548)

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators | b | SE | b | SE |

| Substance use | 0.40*** | 0.07 | 0.30*** | 0.08 |

| Lifetime abuse | 0.26*** | 0.03 | 0.27*** | 0.03 |

| Community violence | 0.35*** | 0.07 | 0.36*** | 0.07 |

| Partner violence | 0.11*** | 0.01 | 0.11*** | 0.01 |

| Consistent condom use | −0.09 | 0.08 | – | – |

| Partner risk | 0.21*** | 0.02 | 0.19*** | 0.02 |

| STI history | 0.21* | 0.10 | 0.22* | 0.10 |

| Depressive symptoms | 7.00*** | 0.71 | 7.28*** | 0.73 |

Note. Variance of the latent factor is set to 1. Stage 1 fit: χ2 (16) = 51.805, p < .001, relative χ2 = 3.24, CFI = .85, RMSEA = .06. Stage 2 fit: χ2(11) = 31.12, p < .01, relative χ2 = 2.83, CFI = .91 RMSEA = .06. CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

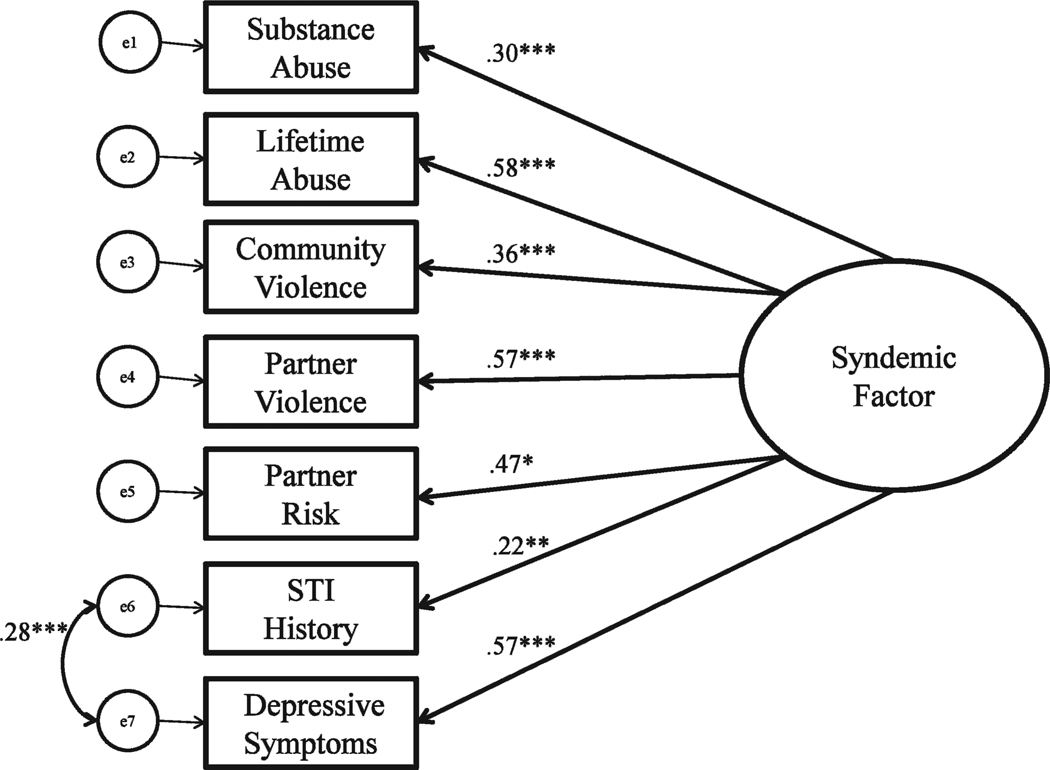

In Stage 2, two revisions were made to the initial model. First, modification indexes indicated the addition of one correlated error term between substance use and partner risk. Second, one indicator, consistent condom use, was removed from the model due to the lack of significant loading. The revised model had a good fit to the data, χ2(11) = 31.12, p < .01 (relative χ2 = 2.83, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .06). All indicators had significant loadings (p < .05) on a single latent factor, except for the one item (depressive symptoms) that set the metric for the model (Table 2). These results suggest that depressive symptoms, partner violence, lifetime abuse, community violence, STI history, partner risk, and substance abuse may be reduced to a single latent variable, consistent with syndemic theory. The significant covariance between errors that was added suggested that another unmeasured factor, in addition to a syndemic factor, may connect substance use and partner risk. The final model with standardized path coefficients is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Standardized loadings for the syndemic measurement model (n = 548). Model fit: χ2(11) = 30.77, p < .01, relative χ2 = 2.80, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .06. CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

In the follow-up analysis, model fit was good, χ2(27) = 53.26, p < .01 (relative χ2 = 1.97, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .04), when two additional correlated errors (partner risk with partner violence and substance abuse with STI history) were added to the model. The latent syndemic factor was not related to poverty, b = −0.14, SE = 0.91, p = .88, or employment, b = 0.28, SE = 0.88, p = .75. However, both percentage of years living in the United States, b = 7.55, SE = 1.53, p < .001, and education, b = −1.98, SE = 0.87, p < .05, were related to the latent syndemic factor. Specifically, a greater percentage of years lived in the United States was associated with a higher level of the latent syndemic factor. Conversely, Latinas with at least a high school education had lower scores on the latent syndemic factor than did Latinas with less than a high school education. Combined, these variables accounted for a moderate amount (9.4%) of the variance in the syndemic factor. These results are partially consistent with the notion that the syndemic is greater for individuals from socioeconomically disadvantaged or other marginalized groups (Singer, 1996, 2009).

Discussion

The results of this study provide evidence that substance abuse, violence, risk for HIV infection, and depressive symptoms represent a syndemic among Latinas in South Florida. It is important to note that consistent condom use, a variable often used to measure HIV risk, did not fit well with the other theoretically related variables and was subsequently removed from the final model.

Condom use may not have been consistent with the other syndemic manifest variables because the baseline frequency of reported consistent condom use was low (15%) and may have not differentiated between high- and low-risk groups. Previous studies including community samples of Latinas found that condom use practices are not related to substance abuse and IPV but may be related to a lack of HIV/AIDS knowledge and to cultural norms restricting open discussions about sex (Abel & Chambers, 2004; González-Guarda et al., 2008; Peragallo et al., 2005; Raj et al., 2004). Some scholars have suggested that HIV risk among women may be more related to their partner’s HIV risk behavior (e.g., sexual and drug history) than their own (Cianelli et al., 2008; Hader et al., 2001; Raj et al., 2004). Gender roles in Latino culture may influence men’s participation in sexual activities with multiple partners, with the expectation that women accept these activities and remain sexually available to their partners, resulting in women’s powerlessness to control risk factors (Peragallo, 1996). Although this hypothesis is not tested, the results of this study suggest that partner HIV risk behaviors and history of STIs are variables that fit better with substance abuse, violence, and depressive symptoms than reported condom use as part of a syndemic among Latinas. Substance abuse and partner risk behavior appear to represent an additional phenomenon to account for when considering this specific syndemic. Latinas reporting substance abuse may be more likely to have a partner also abusing alcohol or drugs and practicing other high-risk behaviors (González-Guarda et al., 2008), placing these women at greater risk for IPV, HIV, and depressive symptoms.

Also consistent with syndemic theory were the positive relationships between the syndemic factor and certain socioeconomic disadvantages. Participants with a higher percentage of years lived in the United States and lower education had higher scores on the syndemic factor. Percentage of years lived in the United States could be an indicator of acculturation. Although little literature is available to connect these factors specifically among Latina women, acculturation has been associated with stress, family conflict, social isolation, risk behaviors, and mental health problems among Latinos (Buchanan & Smokowski, 2009; Caetano et al., 2007). This finding is consistent with previous research linking Latina women’s preference for English (another measure of acculturation) with increased risk for AIDS (Peragallo, 1996). Among Latino men who have sex with men, education has been found also to be related inversely to substance abuse (De Santis et al., 2008), and among Latina women, education has been found to be related inversely to IPV (Lipsky & Caetano, 2007) and HIV risk (Abel & Chambers, 2004). However, incongruent with syndemic theory, poverty and unemployment were not related to the syndemic factor. This may be because traditional gender roles viewing the primary role of women as homemakers in the Latino culture may serve as a buffer against the negative psychological consequences that unemployment and poverty may have among women from cultures that place a stronger value on employment for women (González-Guarda et al., 2008). It is also possible that employment and income were measured at the incorrect level of influence. Neighborhood- or community-level indicators of unemployment and poverty may be more valid measures of socioeconomic vulnerabilities and stronger predictors of the syndemic than those measured at the individual level. The parts that gender, role expectations, and community-level socioeconomic indicators play in shaping this syndemic need further exploration.

This study has important limitations to consider when interpreting results. Participants of this study include a convenience sample of Latinas from South Florida, an area where Latinos come from a wide range of Latin American and Caribbean countries and constitute a large percentage of the total population (e.g., 62% in Miami-Dade County; U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). The convenience sampling also resulted in a sample of women with a high mean score of depressive symptoms on the CES-D (M = 16.41, SD = 12.91), indicating that more than half of the sample were over the clinical cutoff point for this measure (Radloff, 1977). Therefore, caution must be taken when generalizing the results of this study to Latinos in other areas of the United States with different social, demographic, and psychological characteristics. Furthermore, the analysis for this study was not done according to country of origin, language choice, or acculturation—all factors that may have an effect on the syndemic factor. Also, proxy variables were used for socioeconomic disadvantage. More investigation is needed to determine what about living in the United States for a higher percentage of their lives places Hispanic women at risk for the syndemic factor (e.g., acculturation, stress, being separated from family). Finally, these results do not rule out the possibility that alternative models might also fit the data. Nevertheless, this study is the first to test the hypothesis that variation in substance abuse, violence, risk for HIV, and depressive symptoms may be represented by a syndemic factor for Latinas and to identify potential socioeconomic links between these conditions.

Although the results from this study support syndemic theory, most nursing interventions continue to conceptualize and address substance abuse, violence, risk for HIV, and depressive symptoms as isolated problems with distinct risk and protective factors. To meet the nation’s health objectives, the development of more efficient nursing interventions and public health programs and policies targeting these behavioral health conditions in an integrated manner while addressing the common underlying connections is necessary (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008; González-Guarda, 2009). Integrating these will help ensure that the manner in which nurses address behaviorally rooted and mental health problems is aligned with the holistic approach that nurses take to understanding the health of individuals, families, and communities. Nevertheless, to move this more holistic approach to behavioral and mental health forward, interdisplinary research with scientists from other disciplines (e.g., anthropology, epidemiology, psychology) is needed to identify the most important links among substance abuse, violence, HIV, and depressive symptoms among vulnerable populations (i.e., root cause of the syndemic). This study supports the development of nursing interventions that provide support for Latinas transitioning and acculturating to U.S. society and encourages graduation from high school. For example, nurses working in health clinics serving Hispanic immigrants can develop health promotion programs that help their patients adapt and cope positively to the stressors they encounter in the United States. Also, school nurses can work alongside faculty and staff in schools to develop dropout prevention programs. Although social adjustment and education programs have not been viewed traditionally as within the scope of nursing, these approaches appear necessary to address socially rooted syndemic conditions disproportionately affecting Latinos and other vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgments

This article was funded by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (1P60 MD002266-01; Nilda Peragallo, principal investigator).

References

- 1.Abel E, Chambers K. Factors that influence vulnerability to STDs and HIV/AIDS among Hispanic women. Health Care for Women International. 2004;25(8):761–780. doi: 10.1080/07399330490475601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanan RL, Smokowski PR. Pathways from acculturation stress to substance use among Latino adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44(5):740–762. doi: 10.1080/10826080802544216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caetano R, Cunradi C. Intimate partner violence and depression among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Annals of Epidemiology. 2003;13(10):661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Clark CL, Schafer J. Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11(2):123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano Vaeth PA, Harris TR. Acculturation stress, drinking, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the U.S. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22(11):1431–1447. doi: 10.1177/0886260507305568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Syndemics prevention network. [Retrieved December 5, 2010];2008 from http://www.cdc.gov/syndemics/

- 9.Cianelli R, Ferrer L, McElmurry BJ. HIV prevention and low-income Chilean women: Machismo, marianismo and HIV misconceptions. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2008;10(3):297–306. doi: 10.1080/13691050701861439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Santis JP, Colin JM, Vasquez EP, McCain GC. The relationship of depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and sexual behaviors in a predominantly Hispanic sample of men who have sex with men. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2008;2(4):314–321. doi: 10.1177/1557988307312883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González-Guarda RM. The syndemic orientation: Implications for eliminating Hispanic health disparities. Hispanic Health Care International. 2009;7(3):114–115. [Google Scholar]

- 12.González-Guarda RM, Florom-Smith AL, Thomas T. A syndemic model for understanding substance abuse, intimate partner violence, HIV infection, and mental health among Hispanics. Public Health Nursing. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00928.x. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González-Guarda RM, Peragallo N, Urrutia MT, Vasquez EP, Mitrani VB. HIV risks, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic women and their intimate partners. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19(4):252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hader SL, Smith DK, Moore JS, Holmberg SD. HIV infection in women in the United States: Status at the millennium. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(9):1186–1192. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heilemann MV, Lee KA, Kury FS. Strengths and vulnerabilities of women of Mexican descent in relation to depressive symptoms. Nursing Research. 2002;51(3):175–182. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jasinski JL, Asdigian NL, Kaufman Kantor G. Ethnic adaptations to occupation work strain: Work related stress, drinking, and wife assault among Anglo and Hispanic husbands. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12(6):814–831. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Washington CD, Wilson TS, Koob JJ, Davis DR, et al. The effects of HIV/AIDS intervention groups for high-risk women in urban clinics. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(12):1918–1922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipsky S, Caetano R. Impact of intimate partner violence on unmet need for mental health care: Results from the NSDUH. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(6):822–829. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millstein B. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Syndemics Prevention Network; 2008. [Retrieved December 5, 2010]. Hygeia’s constellation: Navigating health futures in a dynamic and democratic world. from the Web site: http://www.cdc.gov/syndemics/pdfs/Hygeias_Constellation_Milstein.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno CL. The relationship between culture, gender, structural factors, abuse, trauma, and HIV/AIDS for Latinas. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(3):340–352. doi: 10.1177/1049732306297387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5th ed. Los Angeles: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newcomb MD, Carmona JV. Adult trauma and HIV status among Latinas: Effects upon psychological adjustment and substance use. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8(4):417–428. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newcomb MD, Locke TF, Goodyear RK. Childhood experiences and psychosocial influences on HIV risk among adolescent Latinas in southern California. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9(3):219–235. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peragallo N. Latino women and AIDS risk. Public Health Nursing. 1996;13(3):217–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1996.tb00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peragallo N, Deforge B, O’Campo P, Lee SM, Kim YJ, Cianelli R, et al. A randomized clinical trial of an HIV-risk-reduction intervention among low-income Latina women. Nursing Research. 2005;54(2):108–118. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raj A, Silverman JG, Amaro H. Abused women report greater male partner risk and gender-based risk for HIV: Findings from a community-based study with Hispanic women. AIDS Care. 2004;16(4):519–529. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001683448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhodes SD, Eng E, Hergenrather KC, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Montaño J, et al. Exploring Latino men’s HIV risk using community-based participatory research. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31(2):146–158. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Research. 1980;2(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romero-Daza N, Weeks M, Singer M. “Nobody gives a damn if I live or die”: Violence, drugs, and street-level prostitution in inner-city Hartford, Connecticut. Medical Anthropology. 2003;22(3):233–259. doi: 10.1080/01459740306770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer M. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology. 1996;24(2):99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer M. Introduction to syndemics. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence and Victims. 2004;19(5):507–520. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Census Bureau. 2006–2008 American community survey. [Retrieved December 5, 2010];2009 from http://factfinder.census.gov.

- 38.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and improving health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy People 2020 public meetings: 2009 draft objectives. [Retrieved December 5, 2010];2009a from http://www.healthypeople.gov/hp2020/objectives/files/Draft2009Objectives.pdf.

- 40.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The 2009 HHS poverty guidelines. Federal Register. 2009b;74(14):4199–4201. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, Gruskin E. Health disparities in Latino populations. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2009;31(1):99–112. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wyatt GE, Myers HF, Williams JK, Kitchen CR, Loeb T, Carmona JV, et al. Does a history of trauma contribute to HIV risk for women of color? Implications for prevention and policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):660–665. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]