Abstract

Rewarding and aversive stimuli evoke very different patterns of behavior and are rapidly discriminated. Here taste stimuli of opposite hedonic valence evoked opposite patterns of dopamine and metabolic activity within milliseconds in the nucleus accumbens. This rapid encoding may serve to guide ongoing behavioral responses and promote plastic changes in underlying circuitry.

Rewards and punishments powerfully shape our behavior. The nucleus accumbens (NAc) integrates sensory and emotional information to guide motor output, and dopamine release in the NAc is thought to promote reward-related learning1 and behavioral responses to incentive stimuli2. It is controversial whether dopamine release in the NAc exclusively signals aspects of reward or serves a more broad purpose for signaling novelty or salience regardless of hedonic value3. Imaging studies have shown increased activity in the NAc in response to both stimuli of differing salience and hedonic valence4. In contrast, electro-physiological evidence has shown differential responding of individual NAc neurons to rewarding and aversive stimuli5 and has shown that aversive, noxious stimuli evoke pauses in the firing rate of dopamine neurons in anesthetized rats6,7 and behaving primates8.

To dissociate salience or novelty from hedonic valence, we delivered brief intra-oral infusions of sucrose and quinine solutions to naive behaving rats and measured changes in dopamine concentration and pH in the NAc (Supplementary Fig. 1 online) every 100 ms using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (see Supplementary Methods online). The pH measurements provide a measure of metabolic activity9 and thus an indirect measure of general neuronal activity. Appetitive (0.3 M sucrose) and aversive (0.001 M quinine) stimuli were delivered intra-orally to ensure equal exposure and transduction via the same sensory modality: the taste system. Each animal received both appetitive and aversive stimuli at unpredictable times to ensure comparable novelty and salience but opposing hedonic valence. This design elicited strong and consistent behavioral differences in hedonic expression with no evidence of anticipatory or conditioned responses (Supplementary Fig. 2 online). Voltammetric recordings permitted real-time detection of dopamine release and NAc activity, elucidating their role in signaling hedonic valence.

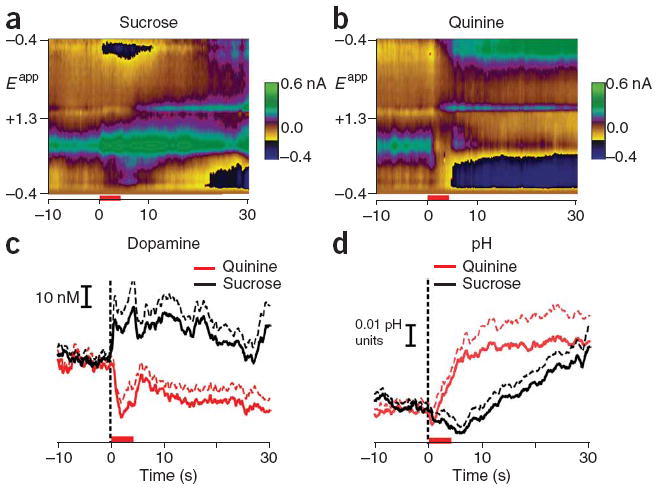

Although dopamine release events (transients) and pH changes were apparent on individual trials of both hedonic stimuli (see Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 online), their frequency and magnitude greatly differed during and in the seconds after the intra-oral infusions. We compared dopamine concentration and pH changes in response to sucrose and quinine infusions averaged across sessions (Fig. 1). The average dopamine concentration in the seconds before infusion onset did not differ between sucrose and quinine trials (21.4 ± 0.26 nM versus 19.3 ± 0.27 nM for sucrose versus quinine, respectively; Tukey’s test, P = 0.19). Intra-oral sucrose infusions evoked a significant rise in dopamine concentration that persisted throughout the post-infusion period (peak dopamine concentration at 4.4 s after infusion onset, 44.0 ± 13 nM, mean ± s.e.m., Tukey’s test, P < 0.001; Fig. 1c). In the quinine sessions (Fig. 1c), dopamine was significantly decreased during the infusion and post-infusion epochs relative to its own baseline (minimum at 1.7 s after infusion onset, 0.00 ± 5 nM, mean ± s.e.m., Tukey’s test, P < 0.001). The observed changes in dopamine concentration were significantly different between sucrose and quinine infusions (F = 238.33, P < 0.001). The decrease in dopamine concentration that we observed during quinine infusions could result from negative prediction error in rats that had previously experienced sucrose infusions. However, it is important to note that decreases in dopamine concentration in response to quinine were apparent and no different in naive rats receiving quinine infusions in comparison to rats that had received a block of sucrose before quinine infusions (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6 online).

Figure 1.

Average fluctuations in chemical signaling in response to rewarding and aversive taste stimuli. (a,b) Voltammetric responses to rewarding (a) and aversive (b) stimuli. The color plots indicate changes in dopamine and pH in response to intra-oral infusions of sucrose (denoted by red bar). Time is the abscissa, the electrode potential is the ordinate and current changes are encoded in color. Average dopamine concentration (identified by its oxidation (~0.6 V) and reduction (~−0.2 V on the negative going scan) features) increased during and after the infusion. In addition, changes in pH can be seen as multiple, longer lasting peaks, with a pronounced peak at ~−0.2 V on the positive going scan. (c) Average dopamine concentration changes for sucrose (mean ± s.e.m. denoted by black solid and broken lines, respectively) and quinine (red). (d) Average pH changes for sucrose and quinine, shown as in c.

Sucrose and quinine infusions also evoked different metabolic activity in the NAc. Again, the baseline pH measurements did not differ in the seconds preceding sucrose and quinine delivery (Tukey’s test, P = 0.22). For the sucrose session (Fig. 1d), pH dropped significantly during the infusion and through 10 s following infusion onset relative to baseline (nadir at 3.6 s after infusion onset, −0.01 ± 0.006 pH units, mean ± s.e.m., Tukey’s test, P < 0.001). pH values then rose and were significantly greater, relative to baseline, through the rest of the post-infusion period (peak at 30 s after infusion onset, 0.03 ± 0.011 pH units, mean ± s.e.m.). For the quinine session (Fig. 1d), pH was significantly higher during all epochs (infusion and 10, 20 and 30 s post-infusion) following infusion onset relative to baseline (peak at 23.2 s after infusion onset, 0.03 ± 0.015 pH units, mean ± s.e.m., Tukey’s test, P < 0.001). Finally, a comparison of the two stimuli revealed that pH during sucrose trials was significantly lower than that during quinine trials for the infusion and post-infusion epochs (F = 146.33, P < 0.001).

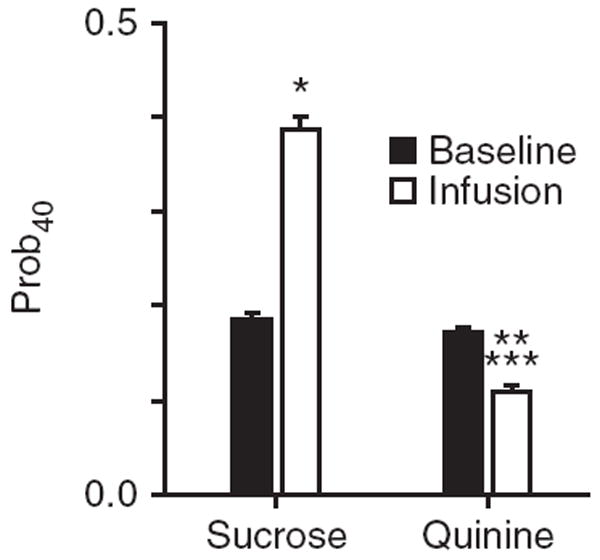

Spontaneous dopamine transients were clearly observed during all epochs on individual sucrose trials and the baseline and post-infusion epochs on quinine trials (see Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 for examples). Although individual release events were typically large (up to 75–100 nM) and brief, the average change in dopamine concentration across trials was closer to ~20 nM, as a result of averaging of release events that were poorly time-locked to trial events. To quantify change in the likelihood of individual release events in response to sucrose and quinine infusions, we evaluated dopamine concentration at every 100-ms time point of each trial to determine whether it exceeded 40 nM. This value was chosen because previous reports from our laboratory have found that the average magnitude of dopamine release events is ~40 nM10. We specifically compared the probability of 40 nM dopamine (Prob40) during the baseline and infusion epochs for sucrose and quinine sessions (Fig. 2). Baseline Prob40 did not differ between sucrose and quinine sessions (0.19 ± 0.09 versus 0.17 ± 0.09 for sucrose versus quinine, respectively, mean ± s.e.m., Tukey’s test, P = 0.16). On sucrose trials, Prob40 increased to 0.39 ± 0.2 during the infusion epoch, whereas on quinine trials, Prob40 decreased to 0.11 ± 0.1 during the infusion epoch. Differences in Prob40 during the infusion epochs for sucrose and quinine were significantly different (F = 397.03, P < 0.001). In awake and behaving primates, rewarding food stimuli evoke increases in the firing rate of presumed dopamine-releasing neurons with short latency11. We found that the likelihood of high concentration dopamine was increased in response to the intra-oral infusion of sucrose within the first 500 ms of the intra-oral infusion (0.29 ± 0.04 versus 0.19 ± 0.02 for infusion versus baseline, respectively, mean ± s.e.m., P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Rewarding and aversive taste stimuli differentially modulate the probability of high increases in dopamine concentration (*P < 0.05 relative to sucrose baseline, **P < 0.05 relative to quinine baseline and ***P < 0.05 relative to sucrose infusion).

Appropriate behavioral output demands that animals rapidly discriminate between stimuli on the basis of hedonic valence. Our results reveal two chemical signals that are involved in this process, dopamine and pH. Dopamine release events and pH levels were equivalent during the baseline periods of sucrose and quinine sessions. Not surprisingly, dopamine concentration increased during and after novel, rewarding sucrose infusions. However, dopamine release events were strongly suppressed during the 4-s intra-oral infusion of quinine. pH changes were also differentially modulated by appetitive and aversive stimuli. Consistent with a recent hypothesis that differential NAc activity reflects appetitive and aversive states12, the majority of NAc neurons respond to appetitive taste stimuli with decreases in firing rate and to aversive taste stimuli with increases in firing rate5,13. The pH measurements that we report here may reflect this differential population activity and suggests a functional link between the two measures. Thus, dopamine signaling and general activity in the NAc is exquisitely sensitive to both rewarding and aversive taste stimuli. In addition, given that intra-oral infusions were unexpected, the data are consistent with the reward prediction error hypothesis of dopamine signaling8,11. The chemical signaling that we observed here may serve to bias motor output toward ingestion or rejection. Alternatively, through precise timing, they may serve to guide future behavior by influencing plastic changes in the NAc14,15. Robust chemical signaling in the NAc encodes information about biologically salient stimuli. However, even when stimuli are equated for novelty, duration of exposure, route of administration and salience, rewarding and aversive stimuli evoke clearly dissociable patterns of chemical signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank M.L.A.V. Heien for programming assistance, S. Ng-Evans and S.A. Wescott for technical assistance, and B.J. Aragona for review of this manuscript. This work was supported by US National Institute on Drug Abuse grants (DA018298 to M.F.R., DA10900 to R.M.W. and DA17318 to R.M.C.).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS M.F.R. and R.A.W. conducted the behavioral and electrochemical experiments and carried out data and graphical analyses. M.F.R. wrote the manuscript and R.A.W., R.M.W. and R.M.C. contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Neuroscience website.

References

- 1.Waelti P, Dickinson A, Schultz W. Nature. 2001;412:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35083500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge KC, Robinson TE. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ungless MA. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:702–706. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper JC, Knutson B. Neuroimage. 2008;39:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Carelli RM. Neuron. 2005;45:587–597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ungless MA, Magill PJ, Bolam JP. Science. 2004;303:2040–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.1093360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coizet V, Dommett EJ, Redgrave P, Overton PG. Neuroscience. 2006;139:1479–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirenowicz J, Schultz W. Nature. 1996;379:449–451. doi: 10.1038/379449a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venton BJ, Michael DJ, Wightman RM. J Neurochem. 2003;84:373–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stuber GD, Roitman MF, Phillips PE, Carelli RM, Wightman RM. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:853–863. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schultz W. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlezon WA, Jr, Thomas MJ. Neuropharmacology. 2008 July 15; doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.075. published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wheeler RA, et al. Neuron. 2008;57:774–785. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabresi P, Picconi B, Tozzi A, Di Filippo M. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arbuthnott GW, Wickens J. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.