Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the role of Ca2+ in lipofuscin formation in human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells that phagocytize bovine photoreceptor outer segments (POSs).

Methods

Cultured human RPE cells fed with 2 × 107 per l bovine POS were treated with flunarizine, an antagonist of Ca2+ channel, or/and centrophenoxine, a lipofuscin scavenger. The Ca2+ changes and lipofuscin formation were measured with fluoresence dye Fluo-3/AM ester, laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) and flow cytometry (FCM). The activity of RPE cells was measured by methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay and argyrophilic nucleolar organizer regions (AgNORs) assay.

Results

The Ca2+ fluorescence intensity (CFI) of RPE cells fed with POS was significantly increased compared with the controls (165.36±29.92 U). It reached a peak with 777.33±63.86 U (P<0.01) at 12 h, and then decreased but still maintained a high level of 316.90±36.07 U (P<0.01) for 4 days. Flunarizine and centrophenoxine significantly decreased the Ca2+ overload to 227.18±14.00 U at 12 h and 211.06±20.45 U at 4 days. FCM confirmed these changes. The drugs also showed an inhibitory effect on the lipofuscin formation. The proliferation rate of the cells fed with POS increased significantly. Both drugs had inhibitory effects on the activity of the cultured cells. This tendency was confirmed by AgNORs assay.

Conclusions

The Ca2+ inflow initiated lipofuscin accumulation in RPE cells fed with POS. Flunarizine and centrophenoxine can decrease Ca2+ overload and lipofuscin formation in RPE cells, accompanied by maintaining cellular vitality.

Keywords: retinal pigment epithelial cell, photoreceptor outer segments, Ca2+, lipofuscin, flunarizine, centrophenoxine

Introduction

Dysfunction of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is highly related to the etiopathogenisis of retinal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD).1, 2 Previous studies suggest that the progressive sediment of lipofuscin, also called age pigment in RPE cells, changes cellular structure and function.3, 4, 5 RPE cells produce lipofuscin by phagocytizing the membranous discs shed by photoreceptor outer segments (POSs). N-retinyl-N-retinlidene ethanolamine (A2E), an essential component of lipofuscin, comes from rod outer segments and has an important role in downregulating RPE cell function in response to light or oxidative damage.6 A2E has another characteristic of autofluorescence because of its phosphorus ingredient in retinaldehyde and vitamin A1 esters.7, 8 We therefore can evaluate the content of lipofuscin in RPE cells by testing the intensity of the cellular autofluorescence.

The process of lipofuscin accumulation involves multiple molecular signal pathways. More evidence indicates that Ca2+ participates as the second messenger in almost the entire molecular signal pathways of all vital cell movement. The balance of the Ca2+ between inside and outside the cell is crucial to cell activity.9, 10 Too much Ca2+ inflow may induce Ca2+ overload and cause the impairment and apoptosis in cells.11 Previous reports have indicated that Ca2+ overload is a final common pathway of cell death.12 Intracellular Ca2+ significantly increases in aging brain cells accompanied by a massive accumulation of lipofuscin.13, 14 A recent study has suggested that lipofuscin deposition is significantly reduced via preventing the dysregulation of intracellular Ca2+ and this benefits the rat's brain.15 The retina is closely related to the brain and they share a lot of similarities. However, the relationship between Ca2+ and lipofuscin in the retina is poorly understood. Here, the experiment was designed to elucidate the pertinent regulatory mechanism(s).

In this study, we investigated the movement of intracellular Ca2+ through the cell membrane during lipofuscin formation in RPE cells fed with bovine POS. In addition, the influence of flunarizine, a Ca2+ channel inhibiter, and centrophenoxine, a lipofuscin scavenger, on Ca2+ overload and the cell viability were also tested. Flunarizine, the fourth generation of Ca2+ channel antagonists, can stabilize the cellular membrane and reduce oxy-radical generation, thus inhibiting the Ca2+ pathological over-inflow.16, 17 Centrophenoxine (also called centrofenoxine or meclofenoxate) is a stimulant of the central nervous system and has been in clinical use for many years. Previous studies have suggested that centrophenoxine can protect the cell membrane by scavenging lipofuscin and oxy-radicals.18, 19 Moreover, we measured the cell activity to monitor the cell condition. We demonstrate here that the Ca2+ balance has an essential role in accumulation of lipofuscin in RPE cells under the phagocytosis.

Materials and methods

Human RPE cell culture

Human RPE cells were cultured from adult healthy donor eyes for keratoplasty, in accordance with the Ethics Committee of Fourth Military Medical University and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. As described previously,20 the anterior segment, vitreous and retina were removed and the posterior eye cup was incubated by 0.025% trypsin-EDTA for 30 min at 37 °C. Dulbecco′s modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Rockville, MD, USA) was then added to the eye cup. The RPE cells were collected and seeded in a culture flask. After reaching confluence, the cells were digested by 0.025% trypsin and transferred to a new culture flask with DMEM containing high glucose, 10% inactivated FBS, and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin. The third or fourth passage cells were used for further experiments.

POS preparation

POS was prepared according to Chaitin MH's protocol.21 The fresh bovine eyeballs were transported by a 4 °C box with sufficient moisture from a slaughter house. The process was completed under a superclean bench to prevent microbial contamination. The eyeball was immersed in 4% gentamycin for 30 min, 75% alcohol for 2 min, and 4% gentamycin for another 30 min. The retina dissociated from eye balls was immersed into D-Hanks solution with 0.025% trypsin-EDTA, churned for 15 min at 4 °C, then stayed at 0 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 3000 r.p.m. for 10 min. The sediments were washed with D-Hanks solution and centrifuged twice. Finally, the sediments were suspended with the cell culture medium and adjusted to 2 × 107 per l.

The POS was identified with a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEM-2000EX, JEOL, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, the fresh POS suspension was centrifuged at 1000 r.p.m. for 5 min, washed by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice. The supernatant was immersed into fixation fluid overnight at 4 °C. Then it was used to make the sample, and the POS was recorded by TEM.

RPE cells fed with POS

In all, 200, 1000, and 5 × 104 cells were planted in 96-well, 24-well with coverslips, and 6-well plates, respectively. When the cells adhere to the plate bottom, the medium was replaced with freshly prepared culture medium containing 2 × 107 per l bovine POS and drug solutions with various densities (flunarizine, 25 μmol/l, Di-Sha, Qingdao, Shandong, China; centrophenoxine, 340 μmol/l, Bang-Da, Jinan, Shandong, China). The cells were cultured and tested for 12 h, 1, 2, and 4 days. The culture medium was changed every 2 days.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM)

For Ca2+ assay, the RPE cells in the 24-well plate were washed with D-Hanks medium twice, incubated with 10 μmol/l Fluo-3/AM ester (diluted with 0.1 M PBS, Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA) for 30 min at 37 °C, and then washed by D-Hanks medium for three times. The Ca2+ fluorescence intensity (CFI) was recorded immediately by a LSCM (FV1000, Olympus, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan). The stretched living cell preparation was putted on an object stage directly and the lipofuscin autofluorescence intensity was measured by LSCM. In each treatment, 50 random cells were chosen to analyze the fluorescence intensity.

Flow cytometry (FCM)

The Ca2+ fluorescence and the lipofuscin autofluorescence intensity in RPE cells were also measured by FCM (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). For CFI assay, the cells in six-well plate were digested with 0.025% trypsin-EDTA, incubated with 10 μmol/l Fluo-3/AM ester for 30 min at 37 °C, centrifuged and washed by D-Hanks medium for three times. The cells were diluted to 5 × 105–5 × 106 cell suspension with fixation solution for FCM. For the lipofuscin autofluorescence intensity assay, the cells were digested with 0.025% trypsin-EDTA, washed by D-Hanks medium twice, and diluted to cell suspension. The fluorescence was measured at 530 nm on FCM with excitation at 488 nm. In each treated experiment, 5000 random cells were chosen by FCM to analyze the fluorescence intensity.

Methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay

When RPE cells were cultured with POS, flunarizine or/and centrophenoxine in 96 well plates for testing hours, 20 μl MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) solution (5 g/l, diluted by PBS solution, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well for 4 h at 37 °C. After the culture medium was removed, the insoluble formazan product dissolved in 150 μl dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well. The optical density of each well was then measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 490 nm. The cell growth curve was drawn and the cell growth rate was calculated. Three wells were repeated for one treatment and the experiment was repeated at least three times.

Argyrophilic nucleolar organizer regions (AgNORs) assay

The cell proliferative ability was assessed by AgNORs. The stretched cell preparation was hydrated with deionized water, and reacted with freshly prepared silver colloidal solution in dark for 40 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were washed with double-distilled deionized water, dehydrated through ascending grades of ethanol and cleared in xylene. The photos were taken and the cell number was counted. In each treated way, 50 random cells were chosen to analyze the number of AgNORs.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean±SD. Statistical analysis was assessed with an unpaired t-test, and differences among groups were considered statistically significant at P<0.01.

Statement

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers/animals were followed during this research.

Results

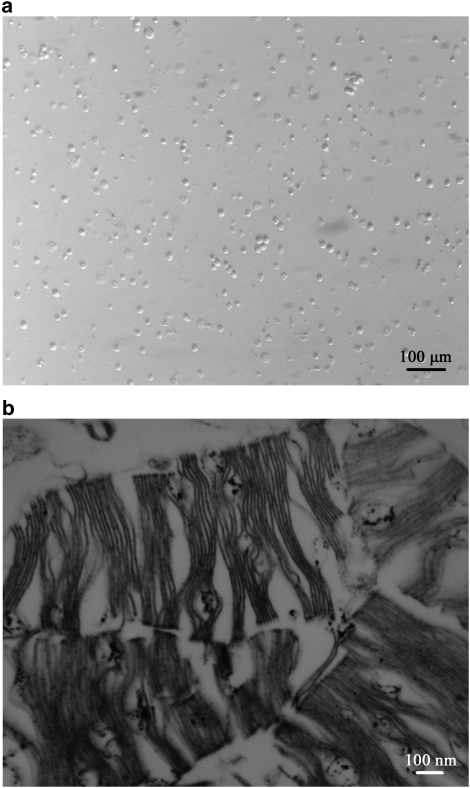

First, the bovine photoreceptors were observed with an inverted microscope. The bovine POS dispersed in the culture medium were uniform, short and rod-shaped (Figure 1a). Under TEM, the fragments appeared to be full of membranous discs. The double membranous discs were make up with the infolded plasma membrane and disposed vertically, parallel or inclined (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Bovine POSs prepared in the culture (a) and their membranous disks under a transmission electron microscope (b).

Under the inverted microscopy, the primary RPE cells were round and contained many pigment granules. After 2–3 passages, the pigment granules diminished, and the RPE cells became polygon-shaped.

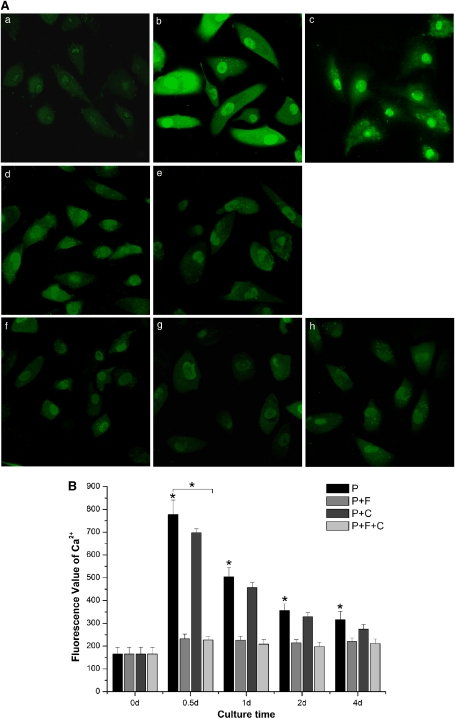

Analysis of Ca2+ and lipofuscin by LSCM and FCM

The fluorescence of Ca2+ was bright in whole RPE cells especially in the nucleus. The CFI of the normally cultured RPE cells was 165.36±29.92 U. CFI of RPE cells fed with POS reached peak with 777.33±63.86 U (P<0.01) at 12 h and then decreased but still maintained a high level of 316.90±36.07 U (P<0.01) for 4 days. However, the CFI in RPE cells cultured with POS, flunarizine and centrophenoxine increased to a lower extent. The CFI of RPE cells cultured with both drugs increased only to 227.18±14.00 U at 12 h and 211.06±20.45 U at 4 days (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The changes of the calcium fluorescence intensity in RPE cells fed with POSs. (A) The fluorescence images of the cells dyed by Fluo-3/AM, ester and recorded by LSCM ( × 600). (a) RPE cells cultured with normal medium. (b–e) The cells fed with POS for 12 h, 1, 2, and 4 days, respectively. (f–h) The cells fed with POS and treated with both of flunarizine and centrophenoxine for 12 h, 1, and 4 days, respectively. (B) Quantification of fluorescence intensity in RPE cells. There is significantly statistical difference in each time interval between controls (0 day) and cells fed with POS (*P<0.01, n=3), and in cells treated with P+F+C compared with cells only fed with POS, especially at 12 h (*P<0.01, n=3). P, the cells fed with POS. P+F, the cells cultured with POS and flunarizine. P+C, RPE cells cultured with POS and centrophenoxine. P+F+C, RPE cells fed with POS and treated with both of flunarizine and centrophenoxine.

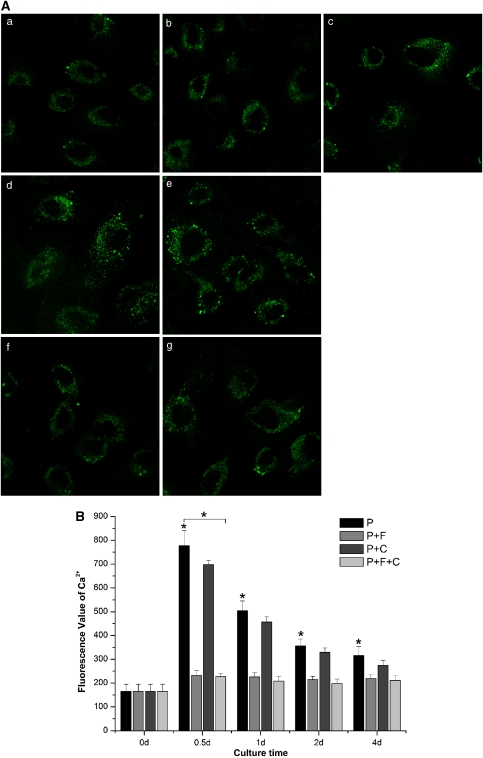

In addition, the lipofuscin autofluorescence analyzed by LSCM of control RPE cells was 105.51±15.39 U. The intensity of RPE cells fed with POS increased to 350.24±26.49 U (P<0.01) after 4 days. The lipofuscin autofluorescence of RPE cells fed with combination of POS and flunarizine or centrophenoxine showed a lower value and reached 123.27±14.52 U (Figure 3) when treated with both drugs.

Figure 3.

The changes of the lipofuscin autofluorescence intensity in RPE cells fed with POSs. (A) The lipofuscin autofluorescence images recorded by LSCM ( × 600). (a) RPE cells cultured with normal medium. (b–e) The cells fed with POS for 12 h, 1, 2, and 4 days, respectively. (f–g) The cells fed with POS and treated with both of flunarizine and centrophenoxine for 12 h, 1, and 4 days, respectively. (B) Quantification of lipofuscin autofluorescence intensity in RPE cells. There is significantly statistical difference between controls (0 day) and cells fed with POS at 4 days (*P<0.01, n=3), and in cells treated with P+F+C compared with cells only fed with POS at 4 days (*P<0.01, n=3). P, the cells fed with POS. P+F, the cells cultured with POS and flunarizine. P+C, RPE cells cultured with POS and centrophenoxine. P+F+C, RPE cells fed with POS and treated with both of flunarizine and centrophenoxine.

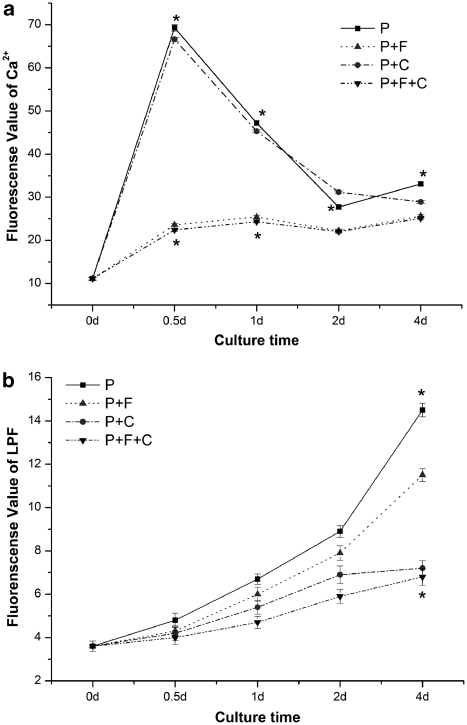

The CFI measured by FCM in RPE cells fed with POS increased almost 6.8-fold (69.3±0.75 U, P<0.01) at 12 h compared with normal RPE cells (11.1±0.36 U) and maintained 3-fold levels (33.1±0.32 U, P<0.01) after 4 days. However, after the combined treatment with flunarizine or centrophenoxine, the intensity increased only two-fold (22.4±0.37 U, P<0.01) at 12 h and 25.1±0.39 U (P<0.01) at 4 days (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

The changes of the Ca2+ fluorescence (a) and lipofuscin autofluorescence (b) intensities in RPE cells fed with POS recorded by FCM. There is significantly statistical difference of Ca2+ fluorescence in each time interval between controls (0 day) and cells fed with POS, especially at 12 h (*P<0.01, n=3), and between the cells treated with P+F+C and cells with POS at 12 h and 1 day (*P<0.01, n=3), which was also confirmed by LSCM. The statistics difference of lipofuscin autofluorescence in cells fed with POS compared with controls is significant at 4 days (*P<0.01, n=3). And the drugs showed suppressing effect on the formation of lipofuscin, especially with P+F+C at 4 days (*P<0.01, versus cells fed with P, n=3). P, the cells fed with POS. P+F, the cells cultured with POS and flunarizine. P+C, RPE cells cultured with POS and centrophenoxine. P+F+C, RPE cells fed with POS and treated with both of flunarizine and centrophenoxine.

The lipofuscin autofluoresence intensity of RPE cells incubated with POS for >12 h persistently increased four-fold (14.5±0.31 U, P<0.01) at 4 days compared with normal RPE cells (3.6±0.24 U, P<0.01). Moreover, when compared with normal cells, the lipofuscin fluorescence intensities in RPE cells treated with flunarizine, centrophenoxine and both drugs were obviously downregulated to 3.2, 2, and 1.9-fold (11.5±0.30, 7.2±0.35, and 6.8±0.39 U), respectively (Figure 4b).

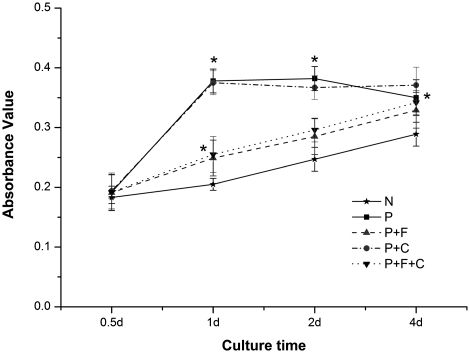

MTT assay

The optical density of the cells fed with POS increased at 12 h, 1, and 2 days, and then decreased at 4 days. The proliferation rate of the cells was 4.9, 84.4, 54.7, and 21.1% for 12 h, 1, 2, and 4 days, respectively. It reached a peak at 1 day and then decreased afterward. Both flunarizine and centrophenoxine had inhibitory effects on the activity of the RPE cells cultured with POS to some extent during 1 to 2 days. Incubation with both drugs had the greatest effect on the cell activity, as indicated by the growth rate of 18.3% at 4 days (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The absorbance value tested by MTT assay. There is significant statistical difference between controls and cells fed with POS at 12 h, 1, 2, and 4 days (*P<0.01, n=3), and between cells fed with both two drugs and only with POS at 12 h (*P<0.01, n=3). N, the growth curve of normal RPE cells. P, the RPE cells fed with POS. P+F, the RPE cells cultured with POS and flunarizine. P+C, the RPE cells cultured with POS and centrophenoxine. P+F+C, the RPE cells fed with POS and treated with both of flunarizine and centrophenoxine.

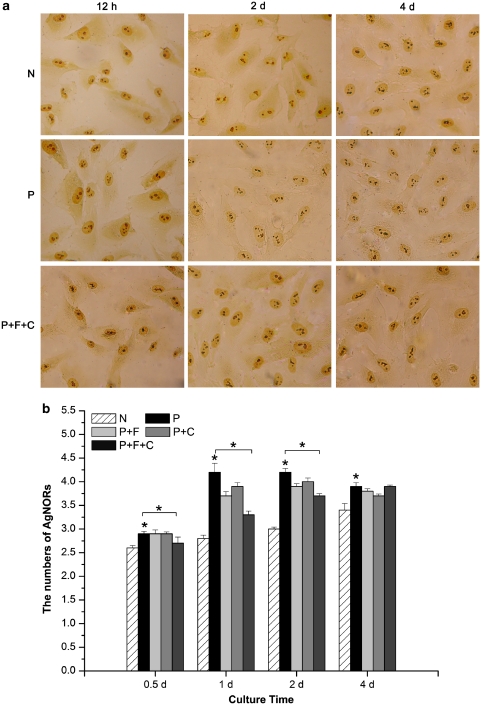

AgNORs assay

Compared with the controls, the number of AgNORs in RPE cells fed with POS increased by 11.5, 50, 50, and 14.7% at 12 h, 1, 2, and 4 days, respectively (P<0.01). However, the count of AgNORs in the RPE cells incubated with POS plus flunarizine, centrophenoxine, or both increased only by 14.3, 39, and 17.9% at 1 day, respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The change of the numbers of AgNORs in RPE cells with various treatments. (a) The images of AgNORs assay in RPE cells at 12 h, 2, and 4 days, respectively. (b) Statistical analysis of AgNORs assay. There is significantly difference in each time interval between controls (0 day) and cells fed with POS (*P<0.01, n=3), and in cells treated with P+F+C compared with cells only fed with POS, especially at 12 h (*P<0.01, n=3). N, normal RPE cells. P, cells fed with POS. P+F, cells with POS and flunarizine. P+C, cells cultured with POS and centrophenoxine. P+F+C, cells fed with POS and treated with both of flunarizine and centrophenoxine.

Discussion

AMD is the most common cause of irreversible central vision loss in elderly patients, and is attributable, at least in part, to phagocytosis, ingestion and digestion of POS by RPE cells.22 Excessive lipofuscin accumulation in RPE cells may cause dysfunction of RPE cells resulting in AMD.23 Previous studies have shown that the ingredient of lipofuscin is complex and mainly comes from POS.3 Several drugs currently under investigation for AMD have the capacity to decrease the rate of POS phagocytosis. In this study, we observed the accumulation of lipofuscin in RPE cells incubated with POS increased along with the time course. Compared with the controls, there was a great abundance of lipofuscin in the RPE cells fed with POS, especially at 4 days. Our results indicate that lipofuscin accumulation of RPE cells results from POS phagocytosis.

Lipofuscin has been found in a variety of postmitotic cells, such as certain neurons, cardiac myocytes, and RPE cells.24, 25 Lipofuscin is often called age pigment and considered as a hallmark of normal senescence and diseases. Recent studies demonstrated that dysregulation of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in other cell types have a crucial role in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease.26 It is well known that Ca2+ is an intracellular messenger involved in various cellular functions. There are almost 104 fold Ca2+ concentration differences between the inside and the outside of the cell.27 Maintaining a low intracellular Ca2+ concentration is vital for keeping cell function, such as proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Some damaging factors, such as ischemia, hypoxia, oxidative stress, and cell toxicant can affect cell membrane permeability or mitochondria condition, leading to intracellular Ca2+ redistribution. Furthermore, Ca2+ influx can trigger various cellular signaling pathways, such as Wnt, Notch, and ERK1/2.28, 29, 30

In this study, we aimed to identify the role of Ca2+ homeostasis in POS phagorytosis in RPE cells. As shown in Figure 2, CFI was significantly increased as indicated by LSCM and FCM especially at 12 h. Lipofuscin accumulated in RPE cells fed with POS especially at 4 days (Figure 3). Therefore, we speculated that phagocytosis of RPE cells switched on the Ca2+ influx. Our results showed that CFI in RPE cells reached an extreme high level (777.33±63.86 U) when RPE cells were fed with POS for 12 h. It is probably due to the different condition of the RPE cells and POS in vitro.

Flunarizine, the fourth generations of Ca2+ antagonist, was chosen to maintain Ca2+ balance in our study because of its unique suppressive effect on overload Ca2+ influx. In the central nervous system, this function of flunarizine can protect the neuron from damage induced by oxidation and ischemia.31, 32 In our experiment, we found that the Ca2+ balance maintained by flunarizine could decrease not only CFI in RPE cells fed with POS (Figure 2), but also cell proliferation (Figure 5). Treating the RPE cells with centrophenoxine, a lipofuscin scavenger, we found that Ca2+ overload diminished along with decrease in the lipofuscin accumulation. In a recent study, Hall et al33 reported that the Ca2+ ionophore could also inhibit POS phagocytosis. Taken together, we conclude that the Ca2+ balance has an important role in the phagocytosis process and the lipofuscin formation.

Furthermore, we found that the proliferation rate of the cells fed with POS was obviously increased especially within 1 day and then decreased quickly and greatly. Both Ca2+ antagonist flunarizine and lipofuscin scavenger centrophenoxine could block these changes. Our results suggest that Ca2+ influx are related to lipofuscin formation in RPE cells as well as cell vitality. On the basis of these results, we propose that these medicines influence RPE cells not only by decreasing the lipofuscin generation but also maintaining the cell vitality.

Despite extensive investigations, the pathogenesis of AMD remains unclear. Here, we suggest that Ca2+ change acts as an important promoter to trigger the cell response to RPE's phagocytosis, but the specific signal pathway and the pertinent mechanism(s) of Ca2+ participation are still unclear.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Post-Graduate Study Foundation in Xijing Hospital of the Fourth Military Medical University. The project was sponsored partly by equipment donation from the Alexander Von Humboldt Foundation in Germany (to YS Wang, V8151/02085).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McConnell V, Silvestri G. Age-related macular degeneration. Ulster Med J. 2005;74:82–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak JZ. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD): pathogenesis and therapy. Pharmacol Rep. 2006;58:353–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Boulton M. RPE lipofuscin and its role in retinal pathobiology. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton S, Southwick K, Hardman RM, Secrest AM, Grow RK, Xin H, et al. Examining the proteins of functional retinal lipofuscin using proteomic analysis as a guide for understanding its origin. Mol Vis. 2005;11:1122–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell SR, Wang P, Divald A, Teichberg S, Haridas V, McCloskey TW, et al. Aggregates of oxidized proteins (lipofuscin) induce apoptosis through proteasome inhibition and dysregulation of proapoptotic proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1093–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldred GE, Lasky MR. Retinal age pigments generated by self-assembling lysosomotropic detergents. Nature. 1993;361:724–726. doi: 10.1038/361724a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shabat S, Parish CA, Vollmer HR, Itagaki Y, Fishkin N, Nakanishi K, et al. Biosynthetic studies of A2E, a major fluorophore of retinal pigment epithelial lipofuscin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7183–7190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb LE, Simon JD. A2E: a component of ocular lipofuscin. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;79:127–136. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2004)079<0127:aacool>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger RF. Physiology and pathophysiology of calcium homeostasis. Z Kardiol. 2000;89:4–8. doi: 10.1007/s003920070093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laude AJ, Simpson AW. Compartmentalized signalling: Ca2+ compartments, microdomains and the many facets of Ca2+ signalling. FEBS J. 2009;276:1800–1816. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SS, Hajnoczky G. Calcium, mitochondria and apoptosis studied by fluorescence measurements. Methods. 2008;46:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Saikumar P, Weinberg JM, Venkatachalam MA. Calcium in cell injury and death. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:405–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toescu EC, Verkhratsky A. The importance of being subtle: small changes in calcium homeostasis control cognitive decline in normal aging. Aging Cell. 2007;6:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhoff G, Busche MA, Garaschuk O. In vivo calcium imaging of the aging and diseased brain. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35 (Suppl 1:S99–S106. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali G, Panneerselvam KS, Panneerselvam C. Age-associated alterations of lipofuscin, membrane-bound ATPases and intracellular calcium in cortex, striatum and hippocampus of rat brain: protective role of glutathione monoester. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2008;26:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels PJ, Leysen JE, Janssen PA. Ca++ and Na+ channels involved in neuronal cell death. Protection by flunarizine. Life Sci. 1991;48:1881–1893. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edward DP, Lam TT, Shahinfar S, Li J, Tso MO. Amelioration of light-induced retinal degeneration by a calcium overload blocker. Flunarizine. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:554–562. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080040122042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton M, McKechnie NM, Breda J, Bayly M, Marshall J. The formation of autofluorescent granules in cultured human RPE. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:82–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R, Nehru B. Effect of centrophenoxine against rotenone-induced oxidative stress in an animal model of Parkinson's disease. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YS, Hui YN, Wiedemann P. Role of apoptosis in the cytotoxic effect mediated by daunorubicin in cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2002;18:377–387. doi: 10.1089/10807680260218542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaitin MH, Hall MO. Defective ingestion of rod outer segments by cultured dystrophic rat pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983;24:812–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:845–881. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty S, Koh H, Phil M, Henson D, Boulton M. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:115–134. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D. Biochemical basis of lipofuscin, ceroid, and age pigment-like fluorophores. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;21:871–888. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Dice JF. When lysosomes get old. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:119–131. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault O, Gant JC, Landfield PW. Expansion of the calcium hypothesis of brain aging and Alzheimer's disease: minding the store. Aging Cell. 2007;6:307–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 1995;80:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod RJ, Hayes M, Pacheco I. Wnt5a secretion stimulated by the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor inhibits defective Wnt signaling in colon cancer cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G403–G411. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00119.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiuza UM, Arias AM. Cell and molecular biology of Notch. J Endocrinol. 2007;194:459–474. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montiel M, Quesada J, Jimenez E. Activation of calcium-dependent kinases and epidermal growth factor receptor regulate muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated MAPK/ERK activation in thyroid epithelial cells. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2138–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Mori Y. Ca2+ channel antagonists and neuroprotection from cerebral ischemia. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;363:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne NN, Wood JP, Cupido A, Melena J, Chidlow G. Topical flunarizine reduces IOP and protects the retina against ischemia-excitotoxicity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1456–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MO, Abrams TA, Mittag TW. ROS ingestion by RPE cells is turned off by increased protein kinase C activity and by increased calcium. Exp Eye Res. 1991;52:591–598. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90061-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]