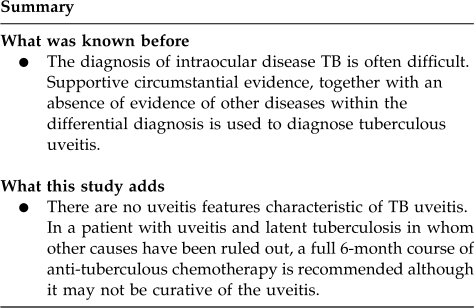

Abstract

Purpose

To assess the effectiveness of anti-tuberculous treatment in patients with chronic uveitis and either active systemic or latent tuberculosis (TB) in a non-endemic community.

Methods

Retrospective study of patients with chronic uveitis, non-ocular evidence of latent or active TB and no other identified cause of uveitis who underwent a 6-month course of standard anti-tuberculous chemotherapy. Response to treatment was assessed at 6 and 12 months after initiation of treatment.

Results

A total of 27 patients were included of whom 59% were female. In all, 19 were Asian, 4 Caucasian, and 4 Black. More than half of patients had a history of contact with another person treated for TB. Inflammation resolved after chemotherapy in 70.3% of patients, 18.5% had a change in the nature of their inflammation and 11.1% had no benefit.

Conclusions

There were no uveitis features characteristic of TB uveitis and a wide range of manifestations was seen ranging from non-granulomatous anterior uveitis to occlusive retinal vasculitis. TB is not endemic in the United Kingdom, therefore consideration of ethnicity, immigration, and history of TB contact remain important to direct investigations. In a patient with uveitis and latent TB, a full 6-month course of anti-tuberculous chemotherapy is recommended although it may not be curative of the uveitis.

Keywords: presumed tuberculous uveitis, anti-tuberculous treatment (ATT), response to ATT

Introduction

In 2007, there were 9.29 million new cases of tuberculosis (TB) worldwide.1 In the United Kingdom, a non-endemic country, the current incidence is 13.8 per 100 000 population, the highest being in immigrants from the Indian subcontinent (36% of total) and sub-Saharan Africa (24%). The incidence of TB in the northwest of England is 11 per 100 000 population but there are pockets of high incidence in the City of Manchester, which has an overall incidence of around 40 per 100 000 population.2

Uveitis may be seen concurrently with TB, but a direct association may be difficult to prove.3 Evidence of active TB at another site, immune response to TB antigens (either as a tuberculin skin test or γ-interferon test) or response to an empirical trial of anti-tuberculous treatment (ATT), in the absence of other plausible causes, may be taken as evidence to support a diagnosis of TB-associated uveitis. In this retrospective study, we assessed the effect of ATT in patients with uveitis and either active systemic TB or latent TB, who had no other demonstrable cause for their uveitis.

Materials and methods

Patients with uveitis and possible TB diagnosed between September 1992 and December 2007 were identified from the database of the Manchester Uveitis Clinic4 and cross-referenced for confirmation with the Manchester Royal Infirmary TB Clinic. Data are entered prospectively and stringently into the uveitis clinic database by one of us (NPJ) and we are confident that case identification is reliable. Comparison with the Manchester Royal Infirmary TB Clinic database confirmed cases but did not identify new cases. Patients were classified with possible TB if, in the presence of uveitis, there was either evidence of active TB at another site, or an immune response to TB antigens (either as a tuberculin skin test or γ-interferon test) and if no other cause of uveitis was identified. Patients were included in the study only if a full 6-month course of standard ATT was administered (usually 2 months of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrizinamide, and ethambutol followed by 4 months of rifampicin and isoniazid).5

Data was extracted from clinical records, including age, sex, ethnic origin, country of birth, history of previous TB or contact, tuberculin skin testing and/or γ-interferon testing and treatment details. Ocular status including visual acuity (VA) and degree of inflammation were assessed at the commencement of ATT (baseline), after the completion of treatment (6 months), and 6 months later (12 months). Anterior uveitis was recorded as granulomatous or non-granulomatous based on the appearance of keratic precipitates or iris nodules at presentation. Behaviour of chronic uveitis was classified as fluctuating or unremitting. Details of concurrent oral steroid treatment were noted.

Results

TB-associated uveitis was considered in 45 patients over the study period. This group comprises 1.9% of the total 2368 patients referred to the Manchester Uveitis Clinic during this period. Medical records were no longer available in 5 patients; of the remaining 40, 6 failed to complete a full 6-month course of ATT and 7 had defaulted from follow-up. The remaining 27 patients were therefore included in the study. Of these, 11 (41%) were male and 16 (59%) female with a mean age of 36.1 years at presentation.

All 27 patients were UK residents, of whom 7 were born in UK, 10 in India, 5 in Pakistan, 4 in Africa, and 1 in Bangladesh. In all, 19 (70%) were of Asian ethnicity, 4 were Caucasian and 4 were Afro-Caribbean. Bilateral ocular inflammation was present in 21 patients (78%). At presentation, 13 had chronic panuveitis, 4 intermediate uveitis, 4 retinal vasculitis, 3 chronic anterior uveitis, 2 multifocal choroiditis, and 1 classical serpiginous choroiditis (Table 1). Seven patients (26%) had granulomatous keratic precipitates and 4 had macular oedema.

Table 1. Clinical features and outcomes of anti-tuberculous treatment in study group.

| Pt. no. | Age at diagnosis | Sex | Country of birth | Description of uveitis | Type | Eye | ? TB | TB contact | CXR | TST | G-IFN | Start dose of steroid | Steroid Rx duration | R VA at presentation | L VA at presentation | R VA at 12 m | L VA at 12 m | Final diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26 | M | India | REV | NGR | B | Smear +ve pulm TB | N | Active | Not done | Not done | 60 | 24 | 6/5 | 6/5 | 6/36 | 6/5 | TB uveitis |

| 2 | 45 | F | India | CAU | GRA | B | N | N | Clear | ++ | Not done | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | TB uveitis | ||

| 3 | 53 | M | Pakistan | CPU | NGR | B | N | N | Clear | ++ | Positive | 60 | 8 | 6/12 | 2/36 | 6/60 | 2/36 | TB uveitis |

| 4 | 42 | F | UK | GEO | NGR | B | N | Y | Old focus | ++ | Not done | 3/60 | 6/9 | 3/60 | 6/6 | Non TB- serpiginous | ||

| 5 | 33 | F | Pakistan | EAL | NGR | B | N | N | Clear | ++ | Not done | 40 | 6 | 6/12 | CF | 6/6 | CF | TB uveitis |

| 6 | 18 | F | UK | CPU | NGR | B | N | Y | Clear | + | Positive | 40 | 12 | 6/9 | 6/9 | 6/12 | 6/6 | Unknown |

| 7 | 45 | F | India | INT | NGR | R | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Not done | 3/60 | 6/9 | 6/36 | 6/6 | Unknown | ||

| 8 | 3 | F | UK | CPU | NGR | B | N | Y | Hilar nodes | ++ | Not done | 6/9 | 6/6 | 6/9 | 6/9 | Unknown | ||

| 9 | 38 | M | India | MCH | NGR | B | N | N | Clear | ++ | Not done | 60 | 7 | 6/6 | 6/24 | 6/5 | 6/5 | TB uveitis |

| 10 | 35 | F | Senegal | FCH | GRA | B | Old lung | N | Old focus | Not done | Not done | 30 | 7 | 6/4 | 6/9 | 6/5 | 6/9 | TB uveitis |

| 11 | 28 | M | UK | INT | NGR | B | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Not done | 80 | 8 | 6/9 | 6/9 | 6/9 | 6/9 | Sarcoidosis |

| 12 | 50 | F | India | CPU | NGR | B | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Not done | 60 | 12 | 6/24 | 6/18 | 6/18 | 6/18 | TB uveitis |

| 13 | 75 | F | UK | CPU | NGR | B | Old lung | N | Old focus | Not done | Not done | 80 | 13 | 6/36 | 6/36 | 6/9 | 6/12 | TB uveitis |

| 14 | 35 | F | India | CPU | GRA | B | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Not done | 60 | 8 | 6/18 | 6/60 | 6/9 | 6/60 | TB uveitis |

| 15 | 46 | M | India | INT | NGR | R | Smear + pulm TB | N | Active | ++ | Not done | 80 | 10 | 6/18 | 6/4 | 6/6 | 6/4 | TB uveitis |

| 16 | 60 | F | Pakistan | CAU | NGR | B | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Not done | 40 | 12 | 6/18 | 6/18 | 6/9 | 6/9 | TB uveitis |

| 17 | 55 | F | UK | CPU | GRA | L | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Positive | 80 | 12 | 6/6 | 6/36 | 6/6 | Hm | TB uveitis |

| 18 | 19 | F | Pakistan | CPU | GRA | R | N | N | Clear | ++ | Not done | 60 | 5 | 6/60 | 6/6 | NPL | 6/6 | TB uveitis |

| 19 | 32 | M | Gambia | CPU | GRA | R | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Positive | 6/12 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | Unknown | ||

| 20 | 35 | M | Sudan | MCH | NGR | B | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Not done | 40 | 9 | 6/5 | 6/9 | 6/5 | 6/5 | TB uveitis |

| 21 | 23 | M | Pakistan | EAL | NGR | B | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Not done | 60 | 12 | 6/5 | 6/36 | 6/6 | 6/6 | TB uveitis |

| 22 | 46 | F | Bangladesh | INT | NGR | L | N | N | Old focus | ++ | Not done | 6/4 | 6/9 | 6/6 | 6/6 | TB uveitis | ||

| 23 | 19 | F | India | APU | GRA | B | N | N | Clear | ++ | Not done | 40 | 6 | 6/12 | 6/12 | 6/6 | 6/9 | TB uveitis |

| 24 | 27 | M | UK | CPU | NGR | B | N | N | Clear | ++ | Not done | 6/60 | 6/24 | 1/60 | 6/6 | TB uveitis | ||

| 25 | 32 | M | India | AAU | NGR | B | Spine | N | Clear | Not done | Not done | 6/6 | 6/36 | 6/6 | 6/18 | Unknown | ||

| 26 | 23 | M | India | EAL | NGR | B | N | Y | Clear | ++ | Not done | 60 | 5 | 6/6 | 6/9 | 6/6 | 6/6 | TB uveitis |

| 27 | 34 | F | Gambia | INT | NGR | B | N | Y | Hilar nodes | ++ | Not done | 60 | 7 | 6/9 | 6/9 | 6/6 | 6/6 | Sarcoidosis |

Abbreviations: APU, acute panuveitis; AAU, acute anterior uveitis; B, bilateral; CAU, chronic anterior uveitis; CPU, chronic panuveitis; CXR, chest X-ray; FCH, focal choroiditis; GEO, geographic choroiditis; G-IFN, gamma-interferon testing GRA, granulomatous; INT, intermediate uveitis; L, left; MCH, multifocal choroiditis; N, no; NGR, nongranulomatous; R, right; REV, retinal vasculitis; TST, tuberculin skin test +, positive; ++, strongly positive; Y, yes.

Fourteen patients (52%) had at some stage been in close contact with a family member treated for TB, but none had received TB prophylaxis. Chest X-ray was normal in 19, 6 showed signs indicative of old TB infection and 2 showed features consistent with active pulmonary TB. Twenty-three patients underwent Mantoux skin testing. All showed 10 mm or more of induration (with the exception of one patient who was considered positive despite only 6 mm induration, because of concurrent high-dose oral corticosteroid therapy).6 Four patients did not require tuberculin skin testing (they had active TB already diagnosed or known past TB). Gamma-interferon testing for latent TB became available in our unit in the later stages of this study period. All four patients tested were positive and these were also positive on tuberculin skin testing (Table 1).

Three patients had evidence of active TB in a non-ocular site; two had pulmonary disease (one with retinal vasculitis, one with intermediate uveitis) and both had complete remission of uveitis 6 months after completion of ATT. The third patient had spinal TB and developed relapsing anterior uveitis at presentation, which became quiescent for several months during ATT, followed by a single recurrence at 6 months.

The uveitis became quiescent during ATT and remained so 6 months later in 16 (67%), of those patients who demonstrated an immune response to TB antigens without evidence of active disease at another site. In five patients (of whom three also received oral steroid treatment), inflammation was controlled during ATT but recurrent anterior uveitis developed at a mean 0.2 months after discontinuing ATT, requiring topical steroids in four and a short course of systemic steroids in one. In the other three patients (all with positive Mantoux test), ATT had no beneficial effect on inflammation. Of these, one had serpiginous choroiditis and required oral immunosuppression and in the remaining two, a reappraisal changed the diagnosis to sarcoidosis.

Nineteen patients required oral prednisolone at a mean starting dose of 57.2 mg/day, tapering for a mean of 9.6 months, owing to the severity of intraocular inflammation. The starting dosage was chosen according to patient weight, severity of inflammation, and the concurrent use of rifampicin (which necessitates higher doses). At the final assessment 6 months after completion of ATT, 13 patients had 2 or more lines improvement in VA compared with presentation, 5 had deteriorated (3 because of cataract, 1 because of macular scarring, and 1 because of corneal scarring) and in 9 there was no change. The visual results of ATT and the final diagnosis are summarised in Table 1.

Discussion

The diagnosis of extra-pulmonary TB is often difficult, nowhere more so than for intraocular disease3 and this is reflected in the absence of information on ocular TB management in any of the TB guidelines of the UK, USA or Canada. Uncommonly, live mycobacteria or their DNA may be accessible from intraocular samples.7 More commonly, intraocular inflammation is either presumed to be a hypersensitivity response rather than direct infection, or possibly mycobacteria are sequestered within the retinal pigment epithelium as has been anecdotally reported.8 In most circumstances, where cultured mycobacteria are unavailable, an accumulation of supportive circumstantial evidence, together with an absence of evidence of other diseases within the differential diagnosis, must be used. The strength of such supportive evidence will be judged via an informal Bayesian analysis by the doctor, in the knowledge of local risk factors, which differ markedly throughout the world.

A primary factor is the population risk for TB. The United Kingdom has in the past 50 years been a very low-risk area for TB acquisition among its indigenous population, which has been partially protected by mass BCG vaccination, a policy that has now been replaced by targeted BCG vaccination in high prevalence areas. In contrast, some countries have a high prevalence of TB and the approach to diagnosis will differ.9 However, increasing immigration to the United Kingdom from high prevalence countries, commencing with those from the Indian sub-continent in the 1960s and followed by many from high-risk areas including Africa and Eastern Europe, have altered the population risk profile.2

The type of uveitis exhibited may suggest TB to the ophthalmologist, although the reasons for this may be unreliable; observations made especially in the early twentieth century (when TB was endemic in the Western world) have taught generations of ophthalmologists to consider certain types of uveitis (particularly granulomatous anterior uveitis, choroiditis, and certain types of retinal vasculitis) more suggestive of TB than other forms of uveitis, an approach used for diagnosis in a recent study.9 However, in the absence of definitive intraocular evidence of aetiology, responsiveness to ATT may indicate the correct diagnosis; our series provides little support for a narrow diagnostic approach; recovery of ‘atypical' uveitis including non-granulomatous anterior uveitis was also seen, suggesting that the ophthalmologist should not exclude the possibility of TB-associated uveitis from the differential diagnosis merely on the basis of clinical appearance. The recent description of ‘atypical serpiginous choroiditis' secondary to TB10 has been both reinforced by further studies11 and widened to include more varied presentations including placoid-like retinitis12 and this reminds us that our diagnostic net should be cast fairly widely.

A certain reliance on non-ocular diagnostic methods is therefore necessary. The great majority of patients will not have evidence of active TB at another extraocular site. Demonstration of the presence of an immune response to TB antigens in the absence of evidence of active TB has been used to characterise the state of ‘latent' TB. This term becomes confusing in the presence of active uveitis; this may be unrelated to the TB immune response, which therefore is truly latent. However, the uveitis may be an ophthalmic manifestation of TB, either directly or via a hypersensitivity mechanism. Despite the absence of other sites of active TB it has been our practice to treat such cases as active TB and as such they are notified.

Tuberculin skin testing may thus be helpful and should be performed, but its predictive value is hampered by variable responsiveness, previous BCG vaccination, the effects of environmental mycobacterial exposure or possible sarcoidosis, and agreements on the relevant diameter of induration, although necessary, are by nature somewhat arbitrary. The predictive value varies depending on the population TB incidence and local BCG vaccination policy; in the United States, the routine use of TB skin testing in patients with uveitis is considered unhelpful13 whereas in India it is considered mandatory.8 In our study, excluding those with active TB all of our patients were Mantoux test positive >10 mm and in the context of any active uveitis without another defined aetiology, this should be considered important guidance. In our clinic, TB skin testing and/or γ-interferon testing is not routinely undertaken for all patients. It is requested for patients with uveitis with a history of contact with TB, of emanating from a TB-endemic area, or where a suggestive uveitis is seen and no other cause is identified.

The confounding issue of previous BCG vaccination is currently the most important reason to consider γ-interferon testing; BCG was derived from M. bovis, which is different antigenically from M. tuberculosis; γ-interferon testing is more specific to M. tuberculosis. In comparing sensitivity and predictive value γ-interferon testing is currently not considered a replacement for tuberculin skin testing as its value for the prediction of development of active TB in the future is as yet not known,14 although interpretation will vary depending on the BCG vaccination policy of the country under study.

In this context, we have evaluated our own clinic's approach to TB diagnosis and management, using a positive response to ATT as a marker for correct diagnosis, and have examined retrospectively the clinical and diagnostic markers leading to the initiation of treatment. The period under study (1992–2007) has seen markedly increasing immigration, the introduction of γ-interferon testing and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for bacterial DNA.15

Our study shows that in 19 patients (70.3%) uveitis disappeared and did not recur 6 months after stopping ATT. The use of oral steroid in the majority of patients is clearly a confounding issue, but the continued absence of inflammation after discontinuing oral steroid reassures us that ATT was effective. This and another recent study16 indicate that for a UK-resident population, in a high proportion of patients with active uveitis, TB is aetiological and not merely an epiphenomenon. In five patients, anterior uveitis developed after discontinuing ATT. We presume that this is an autoimmune phenomenon; similar phenomena are seen sometimes after other intraocular infections including toxoplasmosis and viral retinitis,17 without evidence of ongoing infection and it is likely that a similar mechanism is in play.

In two of our patients, after failed ATT and reappraisal, the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made. The differential diagnosis may be initially difficult as clinical appearances may be similar. Sarcoidosis may suppress the tuberculin skin test response and serum angiotensin converting enzyme may be moderately elevated in TB and normal in sarcoidosis. Chest radiology (including CT), bronchoalveolar lavage and biopsy may also fail to distinguish one from the other. Failed ATT should provoke reinvestigation, and our two cases of a changed diagnosis to sarcoidosis are a demonstration of that diagnostic difficulty.

PCR testing has provided encouraging although unvalidated results for both intraocular18, 19 and other extrapulmonary20 TB. Such tests are not routinely recommended for TB diagnosis in the United Kingdom5 because of poor predictive value, especially false-negative results. The technique is not available at this centre. The aetiology of intraocular inflammation even where directly related to TB, is unproven and the possibility of an autoimmune inflammation in the absence of intraocular mycobacteria, at least for some patients, adds to the concern about false-negative PCR results. More studies on this subject are required.

Anti-tuberculous chemotherapy is not without risk, and hepatic and neurological toxicity are more common in older patients. In our patient group, we did not encounter significant toxicity. In all, 19 of these 27 patients were successfully treated for their uveitis, and of the remainder, 6 were in the recommended age group for treatment of latent TB. Using these diagnostic criteria we feel that the use of ATT is justified by outcomes.

In conclusion, we have retrospectively studied the use of anti-tuberculous chemotherapy in a group of patients from a population with an increasing prevalence of TB and uveitis, showing a high success rate in eliminating uveitis, and no significant treatment toxicity. We recommend a high index of suspicion for tuberculous uveitis and a readiness to use ATT even where tuberculous aetiology has not been proven. Satisfactory response to therapy in the majority of cases has provided support for this approach.

Acknowledgments

Support from the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre is acknowledged.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anon Global tuberculosis control 2009; epidemiology, strategy, financingWorld Health Organisation WHO/HTM/TB/2009.411.

- Anderson C, Moore J, Kruijshaar M, Abubakar I. Tuberculosis in the UK: annual report on tuberculosis surveillance in the UK 2008. London, Health Protection Agency Centre Infect. 2008.

- Alvarez GG, Roth VR, Hodge W. Ocular tuberculosis: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:432–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NP.ed.). Diagnosing uveitis Uveitis; An Illustrated Manual Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Anon Tuberculosis: clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and controlThe National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. London, Royal College of Physicians2006 [PubMed]

- Gupta V, Gupta A, Arora S, Bambery P, Dogra MR, Agarwal A. Presumed tubercular serpiginouslike choroiditis. Clinical presentations and management. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1744–1749. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00619-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas J, Madhavan HN, Gopal L, Badrinash SS. Intraocular tuberculosis: clinicopathologic study of five cases. Retina. 1995;15:461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao NA, Saraswathy S, Smith RE. Tuberculous uveitis: distribution of mycobacterium tuberculosis in the retinal pigment epithelium. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1777–1779. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal R, Gupta A, Gupta V, Dogra MR, Bambery P, Arora SK. Role of anti-tubercular therapy in uveitis with latent/manifest tuberculosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:772–779. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Gupta A, Arora S, Bambery P, Dogra MR, Agawral A. Presumed tubercular serpiginouslike choroiditis: clinical presentations and management. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1744–1749. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00619-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackensen F, Becker MD, Wiehler U, Max R, Dalpke A, Zimmerman S. Quantiferon TB-GOLD—a new test strengthening long-suspected tuberculous involvement in serpiginous-like choroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:761–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyssot N, Bodaghi B, Cassoux N, Fardeau C, Le Mer Y, Ullern M, et al. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy, serpiginous and multifocal choroiditis: etiological and therapeutic management. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2006;29:510–518. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(06)73804-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JT, Wernick R. The utility of routine screening of patients with uveitis for systemic lupus erythematosus or tuberculosis: a Bayesian analysis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1291–1293. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070110107034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albini TA, Karakousis PC, Rao NA. Interferon-γ release assays in the diagnosis of tuberculous uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:486–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000;49:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma D, Anand S, Reddy AR, Das A, Watson JP, Currie DC, et al. Tuberculosis: an under-diagnosed aetiological agent in uveitis with an effective treatment. Eye. 2006;20:1068–1073. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer M, Young S, Lightman S. Anterior uveitis after healed acute retinal necrosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:88–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake S, Kimura K, Yoshikawa K, Sasamoto Y, Matsuda A, Nishikawa T, et al. Polymerase chain reaction for the detection of mycobacterium tuberculosis in ocular tuberculosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117:805–806. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Arora S, Gupta A, Ram J, Bambery P, Sehgal S. Management of presumed intraocular tuberculosis: possible role of the polymerase chain reaction. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1998;76:679–682. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therese KL, Jayanthi U, Madhavan HN. Application of nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR) using MPB 64 gene primers to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in clinical specimens from extrapulmonary tuberculosis patients. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]