Abstract

Lymphocytes are imprinted during activation with trafficking programs (combinations of adhesion and chemoattractant receptors) that target their migration to specific tissues and microenvironments. Cytokines contribute, but, for gut and skin, evolution has cleverly adapted external cues from food (vitamin A) and sunlight (ultraviolet-induced vitamin D3) to imprint lymphocyte homing to the small intestines and T cell migration into the epidermis. Dendritic cells are essential: they process the vitamins to their active metabolites (retinoic acid and 1,25(OH)2D3) for presentation with antigen to lymphocytes, and they help export environmental cues through lymphatics to draining lymph nodes, to program the trafficking and effector functions of naive T and B cells.

Leukocyte chemoattractant and adhesion receptors direct the systemic trafficking and the microenvironmental positioning of the cells of the immune system and control cell-cell interactions that regulate leukocyte activation in inflammation, immunity and immune pathology1–5. Tissue- and inflammation-selective interactions of circulating lymphocytes and other leukocytes with specialized vascular endothelium mediate leukocyte recruitment in an active, multistep process involving tethering (mediated primarily by selectins and α4 integrins) and rolling (in which the enzyme vascular adhesion protein-1 (ref. 6), the lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 (ref. 7) and the hyaluronate receptor CD44 can also participate8,9); chemoattractant-induced rapid integrin activation (mediated by chemokine and other G protein–coupled receptors); activation-dependent firm arrest on the vessel wall (mediated by integrins, especially β2 integrins); and diapedesis in response to chemoattractants. Recruitment can be regulated at any or all of these points, and the implications of this for combinatorial diversity, specificity, and mechanistic resiliency in leukocyte trafficking have been discussed in detail4.

From the perspective of regional physiology and pathology, selective trafficking provides a mechanism for segregating the specialized immune response modalities characteristic of cutaneous versus systemic or intestinal immune responses and for targeting specialized lymphocyte subsets to particular immune microenvironments, such as the B or T cell zones in lymphoid tissues or the epithelial or subcutaneous tissues in the skin. From the perspective of therapeutics, tissue- and microenvironment-specific homing represents an attractive target for the manipulation of localized immune and inflammatory responses.

Recently, substantial progress has been made in identifying cells and molecular mediators that are responsible for imprinting specialized trafficking programs. This review will focus on the emerging appreciation of the roles of external environmental factors and of dendritic cells (DCs), which interpret, process and transport environmental signals, in the regulation of tissue-selective lymphocyte homing.

Skin and intestinal trafficking programming

Specialized combinations of receptors target lymphocytes to particular sites such as the skin, small intestines, peripheral lymph nodes, bronchus-associated lymphoid tissues and gut associated lymph tissues (GALTs), including the Peyer’s patches. Mechanisms involved in skin and small intestinal homing are particularly well characterized; they have been reviewed recently in detail2,3,10,11 and are summarized here because of their specific relevance to our discussion of the environmental control of trafficking programs. Memory T cells specific for cutaneous antigens recirculate selectively through the skin in a process directed by cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA) interaction with vascular E-selectin, variable contributions of α4β1 binding to VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule-1), and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1, composed of αLβ2, also known as CD11aCD18) binding to ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule-1). Participation of chemokine–receptor pairs CCR4–CCL17 and/or CCR10–CCL27 is also required for and helps direct this trafficking to skin12. Additional adhesion molecules, enzymes and chemokines likely contribute as well but have been less well studied13–15. In contrast, small intestine homing T cells use interactions between α4β7 integrin and MAdCAM-1 (mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule-1), LFA-1 and ICAM-1 as well as CCR9 and CCL25. Similar selective, albeit less completely understood, mechanisms are thought to target bronchopulmonary, central nervous system and other site-specific T cell responses16,17. Notably, functionally specialized B cell and T cell subsets often use distinct receptor combinations for homing, allowing control of the functional repertoire of lymphocytes in tissues. As one example, in contrast to mucosal T cells, which are CCR10–, most IgA antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) express CCR10 and use it to respond to the mucosal epithelial chemokine CCL28, which is involved in targeting IgA ASCs to the gut (in combination with α4β7 and MAdCAM1, and probably LFA-1 interactions) and lactating mammary glands and to non-intestinal mucosae (in combination with α4β1 and VCAM-1)18–20.

Historical studies of lymphocyte homing in murine species and recirculation in the sheep led to the hypothesis that the trafficking properties of naive lymphocytes, which localize primarily to the organized lymphoid tissues of the body, are reprogrammed during antigen activation to target effector and memory cells to particular extralymphoid tissues (reviewed in refs. 21,22), and that the local lymphoid environment (rather than the nature of the antigen) was a key determinant of the homing properties induced. This hypothesis was eventually confirmed by demonstrating reprogramming of a homogeneous population of naive T cells expressing a transgenic, monospecific T cell antigen receptor. Activation of these transgenic T cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) rapidly upregulated intestinal homing properties (α4β7 and CCR9), whereas activation within skin-draining (nonmucosal) lymph nodes upregulated selectin ligands associated with peripheral (nonmucosal) tissue trafficking in the mouse23. Thus, during an immune response, local microenvironments within skin-draining and intestinal secondary lymphoid organs differentially direct T cell expression of adhesion and chemoattractant receptors, targeting their effector and memory cell progeny to the inflamed skin or the intestinal lamina propria.

External environmental cues for trafficking

For antigen-activated memory or effector T cells to be ‘instructed’ to home specifically to extralymphoid sites such as the skin or intestines, cues must exist within the lymphoid tissues to provide the instruction. Such cues may include developmentally determined factors, but, in at least two instances, evolution has cleverly co-opted tissue-specific, external environmental stimuli to imprint homing. Vitamin A, which enters the body exclusively through the diet, has been adapted to ‘imprint’ small intestinal homing properties24, and vitamin D3, which is produced at uniquely high amounts in sun-exposed skin, induces T cell tropism for the epidermis25. DCs play a dual role in this process, processing both local antigen and the environmental signals themselves for presentation to responding T cells. DCs also respond to local environmental signals and show regional and functional specialization themselves.

Vitamin A and small intestinal lymphocyte homing

Vitamin A is a dietary, fat-soluble vitamin mainly obtained as retinol from liver and dairy products and as carotenoids from plants. Vitamin A is converted to retinal and then to retinoic acid, which binds to specific retinoic acid receptors (RARs), in the nuclear hormone receptor family26, to mediate pleiotropic effects on gene transcription and cellular differentiation. Although quantitative in vivo surveys of tissue concentrations of vitamin A or its active metabolites are not available, direct assays confirm the small intestines as the primary site of absorption and of enzymatic processing of vitamin A and of beta-carotenoids to retinal; thus, that the small intestines and, by extension, the lymphoid tissues of the GALT may experience uniquely high concentrations of retinoids27.

Recent studies indicate that the induction of small intestine–homing properties in responding T cells is regulated by DC generation and presentation of retinoic acid. Addition of retinoic acid to activated mouse T cells in vitro induces the expression of the gut homing receptors α4β7 and CCR9 while suppressing expression of E-selectin ligands (equivalent to human CLA) associated with skin tropism24 (Fig. 1). DCs isolated from GALT (but not DCs isolated from spleen) express mRNAs encoding the retinal dehydrogenases (RALDH1 and/or RALDH2) needed to convert retinal to retinoic acid. Moreover, GALT DCs are more effective than splenic DCs at mediating this conversion in vitro, and they are better than peripheral lymph node DCs at upregulating the gut homing receptor α4β7 and inducing the small intestine–targeting receptor CCR9 on T cells24. Intestinal epithelial cells also express vitamin A–metabolizing enzymes and by local production of retinoic acid may influence gut T cell responses as well; but the ability of DCs to present both antigen and the environmental cue retinoic acid to T cells is likely important for the efficiency and specificity of the imprinting process. Moreover, intestinal DCs can carry antigen and gut homing-inducing signals to the draining MLN for presentation to naive T cells as well.

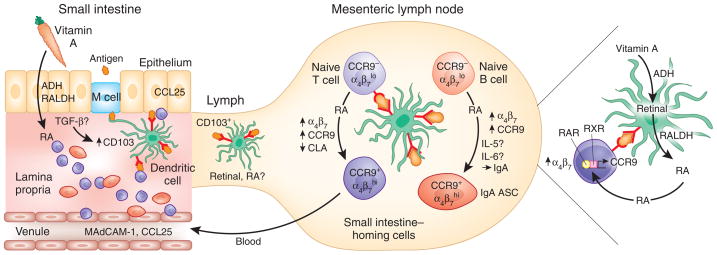

Figure 1.

Vitamin A and the imprinting of small intestine trafficking. Model of diet-induced DC-mediated imprinting of T and B cell trafficking to the small intestines. Vitamin A is obtained through the diet as retinol or as plant carotenes, which are locally processed to retinol. Retinol is oxidized to retinal by alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH), and retinal is then oxidized to the active metabolite retinoic acid (RA) by retinal dehydrogenases (RALDH). The small intestines absorb vitamin A and efficiently process retinol to RA; these retinoids are therefore represented at high concentrations in the gut wall27. DCs in the lamina propria process antigen internalized by M cells and are educated by the local environment. For example, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β activated by the epithelium is hypothesized to upregulate CD103 on a subset of DCs. Mucosal DCs, in particular the educated CD103+ subset, also express enzymes (ADH, RALDH) necessary for processing retinol to RA. Mucosal DCs bearing processed antigen transport it to the draining MLN, where they present it to naive T cells. Retinol bound to protein can be transported through the lymphatics, and DCs, perhaps especially the CD103+ subset, may also transport RA itself as an active cargo. CD103+ DCs from the small intestines induce rapid and robust RA-dependent signaling in antigen-reactive naive T cells in the MLN, efficiently imprinting the T cells with small intestine–homing properties by upregulating CCR9 and α4β7. RA also inhibits induction of the skin homing receptor CLA. Mechanisms responsible for suppression of CCR4 expression on most gut T cells are not understood. Mucosal DCs also support B cell differentiation into small intestine-homing IgA+ ASCs, a process that involves synergy between IL-5 or IL-6, RA and DCs. DCs may present antigen in the context of RA to memory or effector T cells in the lamina propria, as well, potentially reinforcing their expression of small intestine–homing receptors CCR9 and α4β7. MAdCAM, mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; RXR, retinoid X receptor.

In experiments using RAR response element reporter mice, activation of CD8+ T cells in MLNs in vivo results in enhanced RAR signaling compared with activation in the spleen, supporting the hypothesized GALT-selective role of retinoic acid28. Induction of the small intestine homing receptors, especially CCR9, is specifically associated with a CD103+ DC subset that is capable of rapidly inducing RAR signaling events upon T cell priming. Isolated spleen DCs, which do not induce CCR9 in vitro, also enhance RAR signaling in responding CD8+ T cells in vitro, but with delayed timing. Interestingly, CD103+ DCs are abundant in the lamina propria of the small intestines and these DCs (but not CD103+ DCs in colon or lungs) are potent inducers of CCR9 as well29. Integrin α4β7 mediates lymphocyte homing to large as well as small intestines and is more readily induced than CCR9 under diverse conditions in vitro: it is even induced above the low amounts expressed by naive cells during in vitro activation by peripheral lymph node DCs or by antibodies to CD3 and CD28, albeit not to the high levels programmed by retinoic acid (unpublished observations). In contrast, CCR9 is more selectively involved in small intestine homing and is under more stringent retinoic acid–dependent control. The ability of CD103+ DCs from small but not large intestines to induce CCR9 thus supports a preferential role for retinoic acid in the proximal intestines.

These findings, together with the preferential expression of RALDH1 and/or RALDH2 by Peyer’s patches and MLN DCs24, are consistent with the hypothesis that CCR9-inductive DCs are specifically programmed in the small intestines for enhanced retinoic acid production. The gut wall environment, possibly through local activation of transforming growth factor-β, upregulates CD103 on T cells. It is attractive to postulate that the small intestinal environment may induce CD103 and, potentially, retinoic acid synthesizing enzymes in DCs located in the gut wall as well29, and thus that CD103+ CCR9-inductive DCs found in MLNs may have recently arrived in the MLNs through the lymph. If the hypothesis that CCR9-inductive DCs are ‘educated’ in the small intestines is correct, retinoic acid itself could contribute. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) ligands in the gut wall may also play a role, as PPAR-γ upregulates retinoid-metabolizing enzymes and enhances retinoic acid production in human DCs30.

An alternative hypothesis to explain the CCR9-inductive properties of isolated GALT DCs is suggested by the finding that DCs can retain and potentially transport retinoic acid itself. Retinoic acid pretreatment of human monocyte-derived DCs endows them with the ability to induce CCR9 and upregulate α4β7 on T cells; this ability is inhibited by RAR antagonists, confirming an essential role for DC-associated retinoic acid presentation to the T cells31. Unexpectedly, however, this ability is not affected by inhibition of RALDH activity, indicating that de novo DC production of retinoic acid is not involved. Instead, the DCs are able to retain retinoic acid in an active form available to subsequently interacting T cells. DCs are known to acquire antigen locally within tissues for transport through the draining lymphatics. They may also physically transport retinoic acid from the gut wall (and potentially other inductive factors, such as vitamin D3 from skin) for presentation to antigen-reactive T cells in the draining lymph nodes. Such preloading with active retinoic acid could help explain the rapidity of RAR signaling induced by CD103+ GALT DC and their enhanced effectiveness at inducing CCR9.

If retinoic acid in the gut wall either programs DCs or loads them with retinoic acid for induction of CCR9 on T cells one might expect that CCR9 induction and involvement in T cell homing would be most prominent in the proximal small intestines, where dietary vitamin A is first metabolized. Indeed, in mice, the CCR9 ligand CCL25 is expressed in a proximal to distal gradient along the gut, with reduced expression in the ileum; and lymphocyte homing to the proximal small intestines is more highly dependent on CCR9 than is homing to the ileum, where CCR9-independent mechanisms have been implicated32. Enzymatic processing of vitamin A as it enters the small intestines may provide a proximal to distal gradient of retinoids that preferentially supports CCR9 induction, allowing focused homing of T cells responding to proximal small intestinal antigens. The gradient of CCL25 expression along the gut may, however, be influenced in a complex manner by the commensal bacterial community as well33.

Notably, the induction of gut homing receptors by RAR signaling is strongly influenced by antigen dose: DCs pulsed with low antigen doses efficiently and selectively generate CCR9+α4β7+ T cells, whereas high antigen doses actually dampen the induction of α4β7 and CCR9 and reduce homing to the gut28. High antigen doses are associated with enhanced selectin ligand expression, associated with skin homing in the mouse. It would be of interest to determine whether high-dose antigen generates T cells that migrate less specifically (more promiscuously to other tissues) in vivo. Bacterial or viral proteins that activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs) may also modify trafficking profiles34.

Vitamin D3 and T cell epidermotropism

Vitamin D3 is produced in the skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol by the action of sunlight—specifically, ultraviolet B radiation, which penetrates only the outer layers of the skin, the epidermis (Fig. 2a). The highest concentrations of 7-dehydrocholesterol are also found in the epidermis, especially the innermost epidermal layers, the stratum basale and stratum spinosum35. The production of previtamin D3 is therefore greatest in the epidermis adjacent to the underlying connective tissue, the dermis. Once formed, the previtamin undergoes spontaneous but relatively slow heat-induced isomerization to vitamin D3, so that vitamin D3 generation and elevated vitamin D3 concentrations persist for several days after a single sun exposure35,36. In the classical model, vitamin D3 then circulates in the blood and is enzymatically processed, first in liver by the 25-hydroxylases CYP27A1 or CYP2R1 to 25(OH)D3, and then in the kidney by the 1-hydroxylase CYP27B1 to the active 1,25(OH)2D3 (ref. 37), which circulates systemically to control calcium homeostasis. However, it is now clear that keratinocytes38, macrophages39 and DCs25 also express the enzymes required for vitamin D metabolism. Human DCs, in particular, express both 25- and 1-hydroxylase activities (CYP27A1 and CYP27B1) and thus can efficiently convert the sunlight-induced vitamin to the active form for presentation to interacting T cells. Thus, in a situation analogous to the local production of retinoic acid from vitamin A entering the intestinal tract, vitamin D3 is generated at uniquely high concentrations within the skin itself and can be converted locally by DCs to the active form 1,25(OH)2D3.

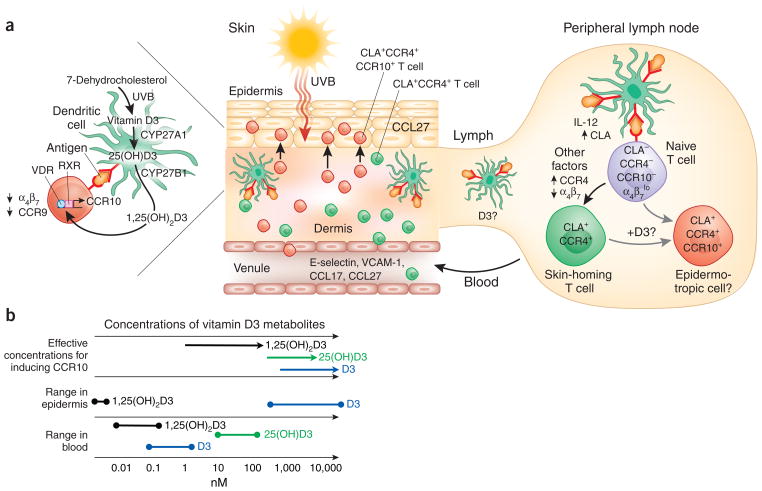

Figure 2.

Sunshine, vitamin D3 and T cell epidermotropism. (a) Model of sunlight-induced T cell epidermotropism in the context of cutaneous antigenic stimulation and DC imprinting of skin T cell trafficking. Sunlight generates vitamin D3 locally in the skin. UVB rays, which penetrate only the outer layers of skin, generate previtamin D3 from 7-dehydrocholesterol, a precursor that is expressed at uniquely high concentrations in the basal epidermis. Over hours to days, the previtamin undergoes spontaneous isomerization to vitamin D3. DCs express the vitamin D3 hydroxylases CYP27A1 and CYP27B1 and, along with keratinocytes, can metabolize the UVB-induced vitamin to its active form, 1,25(OH)2D3. In the sun-exposed skin, antigen-presenting DCs therefore generate and present high concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 to memory or effector T cells, which respond by upregulating CCR10 and migrating to the keratinocyte-expressed epidermal chemokine CCL27. Cutaneous DCs also migrate through the lymphatics to present antigens to naive T cells in lymph nodes. Many antigen-reactive naive T cells are imprinted with a skin homing phenotype (CLA+CCR4hiα4β7–) that directs their trafficking through the blood into the dermis. DC cytokines such as IL-12, which enhances the expression of CLA, are important, but the factors responsible for CCR4 upregulation and, potentially, CCR8 (not shown) expression, and for suppression of α4β7 expression, are not understood. After sun exposure, vitamin D3, or locally generated 25(OH)D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3, may also be transported by DCs or transported bound to transport proteins to the draining lymph node. Vitamin D3 or its metabolites could be presented along with IL-12 and antigen to naive T cells, thus generating an epidermotropic CCR10+, skin-homing T cell population in the primary cutaneous immune response. CLA, cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen; RXR, retinoid X receptor; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; VDR, vitamin D receptor. (b) Concentrations of vitamin D and its metabolites found in human skin and blood. The sun provides a skin-specific signal for imprinting of T cell epidermotropism through the local generation of uniquely high levels of vitamin D3. The effective concentrations of vitamin D3 and its metabolites 25(OH) D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 needed for inducing CCR10 expression on T cells are shown. The concentrations of vitamin D3 found in the skin are sufficient for DCs to induce CCR10 expression on responding T cells. However, the concentrations of vitamin D and its metabolites in the blood (circulation) and reported D vitamin concentrations in intestines and other tissues are too low for the efficient induction of CCR10 (discussed in ref. 25).

1,25(OH)2D3 induces expression of the chemokine receptor CCR10 on proliferating T cells25. Vitamin D3 itself, when added to T cell–DC cocultures at concentrations achieved in the skin after sun exposure, induces CCR10 on a subset of the responding T cells. In contrast, serum concentrations of 25(OH)D3 (the principal circulating form of the vitamin) or of 1,25(OH)2D3 are too low to efficiently induce T cell epidermotropism25 (Fig. 2b). CCR10 can participate in homing of cutaneous memory T cells from the blood into the dermis40, but is not required for recruitment, which can be mediated by CCR4 (refs. 40,41) or, potentially, CCR8 (ref. 14). Instead, CCR10 is thought to be particularly important in targeting T cells from the dermis toward and into the epidermis, as it mediates attraction to CCL27, which is selectively secreted by keratinocytes42. Thus, in sun-exposed skin, CCR10 expression may be induced by vitamin D3 on activated T cells that have been recruited to the dermis from the blood, directing their microenvironmental redistribution toward juxtaepidermal and epidermal sites of ultraviolet-induced tissue damage (Fig. 2a). As vitamin D3 can be transported through the lymph and blood, it is plausible that CCR10 can be induced not only in the skin but, in some circumstances, in response to elevated vitamin D3 concentrations in the skin-draining lymph nodes as well. Given the proposed export of intestinal retinoic acid by gut DCs to the MLNs it will be important to ask whether cutaneous DCs can transport functional amounts of ultraviolet B (UVB)-induced vitamin D3 or its metabolites for presentation in peripheral lymph nodes as well.

1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits the spontaneous upregulation of the gut homing receptor α4β7 on activated human T cells and counteracts the ability of retinoic acid to enhance α4β7 and induce CCR9 expression25. This inhibition of essential gut trafficking receptors by vitamin D3 may help explain the exclusion of CCR10+ memory T cells from the gastrointestinal tract despite expression by mucosal epithelia of the alternative CCR10 ligand CCL28, which mediates CCR10-dependent IgA ASC recruitment to diverse mucosae43. However, vitamin D3 by itself also partially inhibits expression of the skin homing receptors CLA and CCR4, which mediate T cell recruitment into the dermis from the blood. Because these receptors are highly expressed by almost all circulating CCR10+ T cells in vivo, it is clear that more complexity is involved in the physiological control of cutaneous T cell phenotypes and trafficking.

It remains unclear whether vitamin D3 is essential for CCR10 expression on T cells. Indeed, the involvement of CCR10 in T cell homing to cutaneous sites of delayed type hypersensitivity in the mouse40, a nocturnal species, suggests that D3-independent mechanisms may also exist for CCR10 induction in skin-draining lymph nodes. 1,25(OH)2D3 is capable of, but relatively inefficient at, inducing CCR10 on mouse T cells in vitro25; and recent studies indicate that the mouse Ccr10 gene is missing a vitamin D response element that plays a prominent role in human lymphocyte CCR10 induction44. Moreover, although on effector and memory T cell populations CCR10 is restricted to cutaneous T cells, it has also been reported on a subset of suppressor phenotype T regulatory cells in tissues including the liver45, and it is highly expressed by IgA+ plasma cells in mucosal tissues (see below). Together, these considerations suggest that UVB-induced vitamin D3 is a potent inducer of T cell epidermotropism in sun-exposed skin but that CCR10 may be regulated by independent pathways as well.

The parallels between vitamin A upregulation of CCR9-dependent gut homing and vitamin D induction of CCR10-directed epidermotropism are noteworthy. The chemokine ligands involved, CCL25 and CCL27, are both selectively expressed by epithelial cells (small intestinal epithelial cells and keratinocytes, respectively) and are closely related to each other in primary sequence. Receptors for both retinoic acid and 1,25(OH)2D3 belong to the superfamily of ligand-activated heterodimerizing nuclear hormone receptors (NHRs) and share a common partner, the retinoid X receptor (RXR)46. It is possible that the vitamin-regulated epidermal and intestinal homing programs evolved from a primordial common regulatory system for targeting immune cells to epithelial surfaces. NHRs as a family often mediate metastable transcriptional responses, and they thus represent an elegant evolutionary choice for malleable imprinting of lymphocyte migratory properties as a function of environment. The transcriptionally controlled trafficking programs provided by the vitamin D receptor VDR (for CCR10 expression) and the retinoic acid receptor RAR (for CCR9 and α4β7) may be reinforced by periodic reexposure to their nuclear hormone receptor ligands during the recirculation of lymphocytes through their target tissues, but the progeny of skin- or gut-homing T cells can be redirected upon activation by antigen in a different environmental context; for example, in central lymphoid sites such as the spleen5,47,48. It is attractive to postulate that NHRs responsive to other environmental ligands may regulate homing to the colon, lungs, liver or genitourinary tract.

Retinoic acid and 1,25(OH)2D3 have complex effects on DC and T cell biology in addition to their roles in imprinting lymphocyte trafficking. Retinoic acid and 1,25(OH)2D3 both inhibit T cell proliferation, suppress TH1 differentiation (interferon-γ production) and enhance regulatory T cell generation49–57. Consistent with a physiologic role for retinoic acid in this context, GALT DCs (especially CD103+ DCs) promote the generation of regulatory T cells and suppress TH-17 development through an RAR-dependent mechanism56. The immunosuppressive effects of the vitamin metabolites may serve to moderate immune responses in the gastrointestinal tract and in sun-exposed skin; they also likely underlie the effectiveness of RAR and VDR agonists in the treatment of psoriasis58 and of autoimmune diseases in animal models59,60. Clearly, however, these functional properties are under more sophisticated and complex control in vivo, as gut-homing T cells include effector TH1 as well as TH2, TH-17 and regulatory T cell populations. These considerations underscore the complex involvement of 1,25(OH)2D3 and retinoic acid in immune cell responses and the importance of context and microenvironment in defining their effects.

Vitamin cues in IgA ASC trafficking

IgA+ plasmablasts arise in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues and traffic through the blood to populate the intestinal lamina propria, bronchial wall or other mucosal surfaces, where they secrete IgA. IgA+ plasmablasts induced by antigens from the small intestines, like memory T cells, use CCR9 and α4β7 to home to the small intestine wall19,61. Many small intestine–associated IgA+ ASCs and all colon- and lung-homing IgA+ plasmablasts also express CCR10, which allows them to respond to the widely expressed mucosal epithelial chemokine CCL28 (refs. 19,43,61). CCR10+ cutaneous memory T cells are excluded from the gut wall because they lack α4β7, required for the efficient interaction with intestinal venules involved in lymphocyte recruitment. Conversely, most CCR10+ IgA ASCs lack CLA (ref. 62), a key homing receptor for skin.

Recent studies suggest that vitamin A is important in imprinting plasmablast homing to the small intestine63 and that gut-associated DCs are essential for the coordinate expression of CCR9 and the IgA immunoglobulin isotype during the GALT response to small intestinal antigens. As for T cells, retinoic acid presented by GALT-DCs during B cell stimulation enhances α4β7 and induces CCR9 on the responding cells. DCs from MLN also enhance IgA production, an effect that is amplified by retinoic acid but also requires DC-expressed interleukin (IL)-6 or IL-5 (ref. 63). In contrast to the parallel roles of retinoic acid in imprinting CCR9 expression for small intestine T cell24 and plasmablast homing63, the mechanisms that induce CCR10 on IgA+ plasmablasts are less clear. 1,25(OH)2D3 induces CCR10 on human B cells44, but whether this is relevant to mucosal lymphoid tissue induction of CCR10 remains to be determined. Vitamin A deficiency but not vitamin D deficiency has been linked to a reduction in mucosal IgA+ ASCs; CCR10 expression on IgA+ plasmablasts does not require vitamin D or its receptor in mice; and it is unclear whether the concentration of 1,25(OH)2D3 in mucosaassociated lymphoid tissues is sufficient to induce CCR10 expression. Thus, distinct mechanisms, yet to be determined but independent of RAR or VDR signaling, are likely to control CCR10 expression by IgA+ ASCs.

Context-dependent roles for cytokines

Cytokines, crucial effectors and regulators of immune responses, also regulate lymphocyte trafficking, but they do so in a context-dependent manner that as of yet is poorly understood64. As one example, the TH1 cytokine IL-12 induces and the TH2 cytokine IL-4 suppresses CLA expression on in vitro activated T cells65,66; but these cytokines have the opposite effect on the skin homing chemokine receptor CCR4, which is upregulated by IL-4 and suppressed by IL-12 (ref. 67). This discordant regulation of these receptors in vitro does not, of course, reflect physiologic expression patterns, as the migration of TH cells into the skin is directed by CLA and CCR4 together. It is likely that physiologic imprinting, which must induce the coordinated expression of specific receptor combinations to target homing of different functional T and B cell subsets, also requires the coordinated activity of multiple cytokines in the context of environmental cues. Moreover, imprinting in vivo is likely to involve not only combinatorial signaling but also sequential exposure to external environmental and cytokine cues during the evolution of antigen-dependent T cell and DC responses.

Conclusion

The immune system takes advantage of simple vitamin cues from food and sunlight to help differentially target immune responses to the small intestines and the epidermis. DCs are key in this process, functioning, in a broad sense, as both interpreters and exporters of local environments. They not only process antigens, metabolically activate vitamin cues and respond to local cytokines, they also transport the processed environmental signals to draining lymphoid tissues for presentation to lymphocytes. Lymphocytes in turn respond to the antigenic and tissue-specific signals with functional specialization (for example, specialized isotype switching or cytokine responses) and with upregulation of trafficking receptors to target them to sites similar to those where the DCs acquired their environmental information. In addition to imprinting tissue-selective migration of effector and memory cells, DCs may target functionally distinct lymphocyte subsets elsewhere as well; for example, to germinal centers in the case of B helper T cells68.

In spite of the advances outlined here, however, many aspects of the imprinting and control of trafficking programs remain to be clarified. The in vitro environments reconstructed to date with GALT or skin-draining lymph node DCs neither recapitulate the speed nor reconstitute completely the phenotypes observed during T cell imprinting in vivo. For example, α4β7, which is expressed at low but functional levels by naive lymphocytes, is efficiently downregulated during T cell responses in non-gut-associated lymph nodes in vivo, but not in in vitro models, even when activated by skin-associated DCs. Conversely, CCR4 is absent on most or all intestinal T cells in vivo but is only in part suppressed by retinoic acid. Recent studies demonstrate the importance of trafficking receptors for tissue-selective regulatory T cell (Treg) function in vivo69,70, but whether distinct as well as common systems imprint homing of Treg versus TH subsets is unclear. Moreover, cells and factors responsible for programming lymphocyte homing to other tissues such as the colon, lung, central nervous system, oral cavity and genitourinary tract remain to be determined.

Defining the environmental cues and the processing events involved in targeting in vivo immune responses will provide new opportunities for therapeutic control of lymphocyte trafficking, with potential applications to enhancing the efficiency of vaccine-induced immunity and to suppressing the pathology of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Habtezion and C. Oderup for critical comments on the manuscript. Supported by Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award AI 66835-01A1 (H.S.); by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants AI72618, AI47822, AI059635, GM37734 and U19 AI057229 and a Merit Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (E.C.B.); and by the FACS Core Facility of the Stanford Digestive Disease Center under NIH grant P30 DK56339.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

References

- 1.Luster AD, Alon R, von Andrian UH. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1182–1190. doi: 10.1038/ni1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansson-Lindbom B, Agace WW. Generation of gut-homing T cells and their localization to the small intestinal mucosa. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:226–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schon MP, Zollner TM, Boehncke WH. The molecular basis of lymphocyte recruitment to the skin: clues for pathogenesis and selective therapies of inflammatory disorders. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:951–962. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butcher EC. The multistep model of leukocyte trafficking: a personal perspective from 15 years later. In: Hamann A, Engelhardt B, editors. Leukocyte Trafficking: Molecular Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targets, and Methods. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2005. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stolen CM, et al. Absence of the endothelial oxidase AOC3 leads to abnormal leukocyte traffic in vivo. Immunity. 2005;22:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honjo M, et al. Lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 is a cell-adhesion molecule involved in endotoxin-induced inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1274–1279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337528100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jalkanen S, et al. Lymphocyte migration into the skin: the role of lymphocyte homing receptor (CD44) and endothelial cell antigen (HECA-452) J Invest Dermatol. 1990;94:786–792. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12874646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salmi M, Tohka S, Berg EL, Butcher EC, Jalkanen S. Vascular adhesion protein 1 (VAP-1) mediates lymphocyte subtype-specific, selectin-independent recognition of vascular endothelium in human lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 1997;186:589–600. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mora JR. Homing imprinting and immunomodulation in the gut: role of dendritic cells and retinoids. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:275–289. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salmi M, Jalkanen S. Lymphocyte homing to the gut: attraction, adhesion, and commitment. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:100–113. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupper TS, Fuhlbrigge RC. Immune surveillance in the skin: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:211–222. doi: 10.1038/nri1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arvilommi AM, Salmi M, Kalimo K, Jalkanen S. Lymphocyte binding to vascular endothelium in inflamed skin revisited: a central role for vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:825–833. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaerli P, et al. A Skin-selective homing mechanism for human immune surveillance T cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1265–1275. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunther C, et al. CCL18 is expressed in atopic dermatitis and mediates skin homing of human memory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:1723–1728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wardlaw AJ, Guillen C, Morgan A. Mechanisms of T cell migration to the lung. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:4–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelhardt B, Ransohoff RM. The ins and outs of T-lymphocyte trafficking to the CNS: anatomical sites and molecular mechanisms. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunkel EJ, Butcher EC. Plasma-cell homing. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:822–829. doi: 10.1038/nri1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hieshima K, et al. CC chemokine ligands 25 and 28 play essential roles in intestinal extravasation of IgA antibody-secreting cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:3668–3675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson E, Butcher EC. CCL28 controls immunoglobulin (Ig)A plasma cell accumulation in the lactating mammary gland and IgA antibody transfer to the neonate. J Exp Med. 2004;200:805–809. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butcher EC. The regulation of lymphocyte traffic. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1986;128:85–122. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71272-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young AJ, Hay JB, Mackay CR. Lymphocyte recirculation and life span in vivo. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1993;184:161–173. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78253-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell DJ, Butcher EC. Rapid acquisition of tissue-specific homing phenotypes by CD4+ T cells activated in cutaneous or mucosal lymphoid tissues. J Exp Med. 2002;195:135–141. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwata M, et al. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigmundsdottir H, et al. DCs metabolize sunlight-induced vitamin D3 to ‘program’ T cell attraction to the epidermal chemokine CCL27. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:285–293. doi: 10.1038/ni1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Napoli JL. Retinoic acid biosynthesis and metabolism. FASEB J. 1996;10:993–1001. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.9.8801182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore T. Vitamin A and carotene. VI. The conversion of carotene to vitamin A in vivo. Biochem J. 1930;24:692–702. doi: 10.1042/bj0240692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svensson M, et al. Retinoic acid receptor signaling levels and antigen dose regulate gut homing receptor expression on CD8+ T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:38–48. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson-Lindbom B, et al. Functional specialization of gut CD103+ dendritic cells in the regulation of tissue-selective T cell homing. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1063–1073. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szatmari I, et al. PPARγ controls CD1d expression by turning on retinoic acid synthesis in developing human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2351–2362. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saurer L, McCullough KC, Summerfield A. In vitro induction of mucosa-type dendritic cells by all-trans retinoic acid. J Immunol. 2007;179:3504–3514. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stenstad H, et al. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue-primed CD4+ T cells display CCR9-dependent and -independent homing to the small intestine. Blood. 2006;107:3447–3454. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meurens F, et al. Commensal bacteria and expression of two major intestinal chemokines, TECK/CCL25 and MEC/CCL28, and their receptors. PloS ONE. 2007;2:e677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enioutina EY, Bareyan D, Daynes RA. TLR ligands that stimulate the metabolism of vitamin D3 in activated murine dendritic cells can function as effective mucosal adjuvants to subcutaneously administered vaccines. Vaccine. 2008;26:601–613. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webb AR, Holick MF. The role of sunlight in the cutaneous production of vitamin D3. Annu Rev Nutr. 1988;8:375–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.08.070188.002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holick MF, et al. Photosynthesis of previtamin D3 in human skin and the physiologic consequences. Science. 1980;210:203–205. doi: 10.1126/science.6251551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prosser DE, Jones G. Enzymes involved in the activation and inactivation of vitamin D. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:664–673. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehmann B, Rudolph T, Pietzsch J, Meurer M. Conversion of vitamin D3 to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human skin equivalents. Exp Dermatol. 2000;9:97–103. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2000.009002097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu PT, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reiss Y, Proudfoot AE, Power CA, Campbell JJ, Butcher EC. CC chemokine receptor (CCR)4 and the CCR10 ligand cutaneous T cell-attracting chemokine (CTACK) in lymphocyte trafficking to inflamed skin. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1541–1547. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell JJ, et al. The chemokine receptor CCR4 in vascular recognition by cutaneous but not intestinal memory T cells. Nature. 1999;400:776–780. doi: 10.1038/23495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Homey B, et al. Cutting edge: the orphan chemokine receptor G protein-coupled receptor-2 (GPR-2, CCR10) binds the skin-associated chemokine CCL27 (CTACK/ALP/ILC) J Immunol. 2000;164:3465–3470. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazarus NH, et al. A common mucosal chemokine (mucosae-associated epithelial chemokine/CCL28) selectively attracts IgA plasmablasts. J Immunol. 2003;170:3799–3805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shirakawa AK, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces CCR10 expression in terminally differentiating human B cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:2786–2795. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eksteen B, et al. Epithelial inflammation is associated with CCL28 production and the recruitment of regulatory T cells expressing CCR10. J Immunol. 2006;177:593–603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell. 1995;83:841–850. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mora JR, et al. Reciprocal and dynamic control of CD8 T cell homing by dendritic cells from skin- and gut-associated lymphoid tissues. J Exp Med. 2005;201:303–316. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dudda JC, et al. Dendritic cells govern induction and reprogramming of polarized tissue-selective homing receptor patterns of T cells: important roles for soluble factors and tissue microenvironments. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1056–1065. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boonstra A, et al. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 has a direct effect on naive CD4+ T cells to enhance the development of Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4974–4980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iwata M, Eshima Y, Kagechika H. Retinoic acids exert direct effects on T cells to suppress Th1 development and enhance Th2 development via retinoic acid receptors. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1017–1025. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adorini L. Tolerogenic dendritic cells induced by vitamin D receptor ligands enhance regulatory T cells inhibiting autoimmune diabetes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;987:258–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coombes JL, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-β and retinoic acid dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kang SG, et al. Metabolites induce gut-homing FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:3724–3733. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benson MJ, Pino-Lagos K, Rosemblatt M, Noelle RJ. All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1765–1774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun CM, et al. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mucida D, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gregori S, et al. Regulatory T cells induced by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and mycophenolate mofetil treatment mediate transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 2001;167:1945–1953. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prystowsky JH, Muzio PJ, Sevran S, Clemens TL. Effect of UVB photo-therapy and oral calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) on vitamin D photosynthesis in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:690–695. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90722-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu Y, Mahon BD, Froicu M, Cantorna MT. Calcium and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 target the TNF-α pathway to suppress experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:217–224. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Penna G, Amuchastegui S, Laverny G, Adorini L. Vitamin D receptor agonists in the treatment of autoimmune diseases: selective targeting of myeloid but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:V69–V73. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.07s217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kunkel EJ, et al. CCR10 expression is a common feature of circulating and mucosal epithelial tissue IgA Ab-secreting cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1001–1010. doi: 10.1172/JCI17244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jaimes MC, et al. Maturation and trafficking markers on rotavirus-specific B cells during acute infection and convalescence in children. J Virol. 2004;78:10967–10976. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10967-10976.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mora JR, et al. Generation of gut-homing IgA-secreting B cells by intestinal dendritic cells. Science. 2006;314:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1132742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim CH, et al. Rules of chemokine receptor association with T cell polarization in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1331–1339. doi: 10.1172/JCI13543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wagers AJ, Waters CM, Stoolman LM, Kansas GS. Interleukin 12 and interleukin 4 control T cell adhesion to endothelial selectins through opposite effects on α1,3-fucosyltransferase VII gene expression. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2225–2231. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Picker LJ, et al. Control of lymphocyte recirculation in man. II. Differential regulation of the cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen, a tissue-selective homing receptor for skin-homing T cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:1122–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim CH, Nagata K, Butcher EC. Dendritic cells support sequential reprogramming of chemoattractant receptor profiles during naive to effector T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2003;171:152–158. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Campbell DJ, Kim CH, Butcher EC. Separable effector T cell populations specialized for B cell help or tissue inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:876–881. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huehn J, Hamann A. Homing to suppress: address codes for Treg migration. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:632–636. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sather BD, et al. Altering the distribution of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells results in tissue-specific inflammatory disease. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1335–1347. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]