Abstract

In order to improve the fat suppression performance of in vivo 13C-MRS operating at 3.0 Tesla, a phantom model study was conducted using a combination of two fat suppression techniques; a set of pulses for frequency (chemical shift) selective suppression (CHESS), and spatial saturation (SAT). By optimizing the slab thickness for SAT and the irradiation bandwidth for CHESS, the signals of the –13CH3 peak at 49 ppm and the –13CH2– peak at 26 ppm simulating fat components were suppressed to 5% and 19%, respectively. Combination of these two fat suppression pulses achieved a 53% increase of the height ratio of the glucose C1β peak compared with the sum of all other peaks, indicating better sensitivity for glucose signal detection. This method will be applicable for in vivo 13C-MRS by additional adjustment with the in vivo relaxation times of the metabolites.

Keywords: 13C, MRS, CHESS, spatial saturation (SAT), fat suppression, glucose

Introduction

In vivo carbon-13 magnetic resonance spectroscopy (13C-MRS) is expected to be potentially useful for clinical application, especially to monitor glucose metabolites in the tissues or organs. One such application of glucose monitoring using 13C-MRS is to improve early detection of metabolic change in the liver or muscle and to evaluate post-therapeutic changes in diabetic patients.1–4) Higher static magnetic field (B0) of the MR system is advantageous to detect subtle signals originating from the compounds distributed in vivo, however, heating due to the radio frequency (RF) pulse for decoupling, which is applied to extract each peak of the 13C spectra, increases depending on the B0 strength. To minimize heating and avoid tissue damage, surface coils are employed to detect local signals; however, this method does not permit the supression of the lipid signal. In 13C MRS measurements without stable isotope labeling, natural 13C signals originating from the subcutaneous fat tissue and the visceral lipid signals included in the organ tissue of interest are much larger than those from the target metabolites.

A three-dimensional localization technique such as ISIS5) or outer volume suppression (OVS), which uses six hyperbolic secant pulses,6,7) has been proposed to remove the contamination of 13C lipid signals attributed to extra-cerebral fat tissue.8) The disadvantage of these techniques is the inability to suppress the signals from visceral fat. The following two methods have been employed to suppress lipid signals in 1H MRS, 1) frequency (chemical shift) selective suppression pulses (CHESS)9) based on the frequency difference due to the chemical shift, such as those between a proton of water and that of fat, and 2) spatial saturation (SAT) pulses to reduce all signals included in the slab located on the subcutaneous fat layer. In this study, we performed a phantom model study to validate these two types of lipid suppression pulses and their combination for 13C MRS on a clinical 3.0 Tesla (T) MR scanner. The optimal parameters to achieve lipid suppression in vivo were investigated.

Materials and methods

MR systems for the 13C MRS experiments.

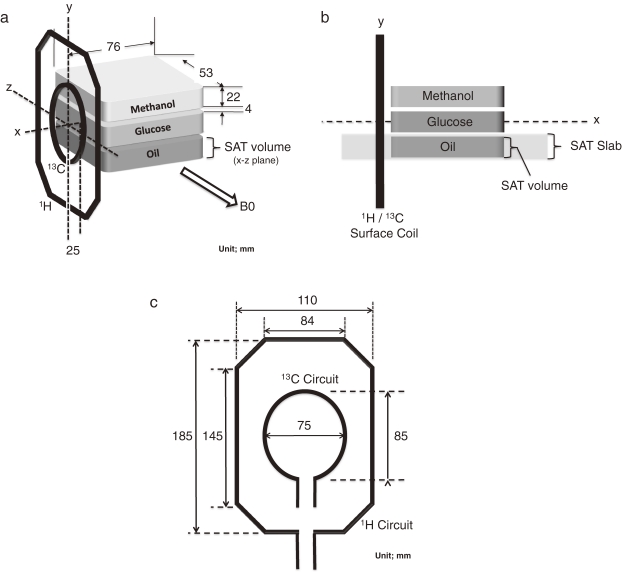

All MRI and MRS experiments were performed with a 3.0 T clinical MR system equipped with a second channel transmit/receive system (Signa VH/i 3.0 T; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). Proton and 13C MR data were obtained using a custom-made transmit/receive surface coil unit (GE Healthcare, Fig. 1) with external dimensions of 195 × 130 mm2. The resonator circuits were designed to be independent of each other. The ellipsoid of the 13C resonator (32.16 MHz) was 85 × 75 mm2, and that of the proton resonator (127.89 MHz) was 185 × 110 mm2 (Fig. 1c). The 13C resonator was located concentrically inside of the proton resonator.

Figure 1.

Design of a phantom study using a pair coil set for 1H and 13C. 1a: The three phantom components were stacked and placed beside the coil surface in the axial view. The surface coil was placed parallel to the B0 direction (in y–z plane). SAT pulse was applied to the slab in x–z plane (1b) covering the oil component (‘SAT volume’ corresponding to the plastic case at the bottom). Using a proton MR image of the phantom, the spatial location of ‘SAT volume’ was automatically configured. CHESS pulse was applied to and 13C spectra were obtained from the whole volume including the three components. 1c: Circuit design of the surface coil pair. The inner oval coil was adjusted for 13C resonance and the outer octagon circuit for 1H. These two circuits are electrically independent.

Phantom preparation.

A phantom was designed to include three components, 99.9% methanol (Aldrich Chemical, Milwaukee, WI), a mixture of canola and soybean oil (Nisshin Oil Group, Tokyo, Japan) and non-enriched D(+) glucose–water solution (3.2 mol/kg, Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). Glucose rather than glycogen was chosen as the target metabolite in this study for better quantification of signal detection. The oil signals imitated the 13C spectra originating from subcutaneous fat, and those of methanol partially simulated visceral fat in an organ. Methanol was employed to simulate the –CH3 peaks of lipid components, since they are located within a similar chemical shift range to the lipid peaks and can be distinguished from other peaks originating from the mixture oil compounds. In order to assess the efficacy of the SAT pulses on each component, the three components were spatially separated in three plastic cases (Fig. 1). The internal dimension of each case was 76 × 53 × 22 mm3.

Pulse sequence for suppressing 13C signals.

CHESS and SAT pulses for 13C-MRS were combined as follows:

| CHESS - SAT - 13C hard pulse - MR signal acquisition |

A single excitation pulse was used for both CHESS and SAT, and the duration times were 50 ms and 10 ms, respectively. The hard pulse duration time for 13C was 250 µs. Selective excitation pulses for CHESS and SAT were designed with the Shinnar–Le Roux algorithm,10,11) which is based on a discrete approximation to the spin domain version of the Bloch equation. The excitation pulses equivalent to the sinc shape were generated by using a series of small hard pulses modulated to represent the waveform amplitude. The center frequency, pulse strength and bandwidth were varied to identify the best condition. The slab volume to be suppressed by applying the SAT pulse with a resonance frequency of 13C was determined by 1H MR imaging. The resonance frequency of 13C (32.16 MHz) at 3.0 T was automatically adjusted depending on that of 1H (127.89 MHz) by a pulse sequence program equipped with a second channel system. The irradiation bandwidth of the RF pulse for SAT slice selection was fixed at 6000 Hz, which corresponded to 5.6 gauss for 13C at 3.0 T. The field gradient strength, which was inversely proportional to SAT slice thickness, was changed to determine the slice thickness:

| (slab thickness (cm)) × (gradient strength (gauss/cm)) = 5.6 gauss |

In this study, the gradient strength was configured to be 2.2 gauss/cm so that the SAT slab covers 25.2 mm thickness depending on the height of the plastic case.

13C MR experiments with two suppression sequences.

The phantom consisting of the three components was placed close to the coil surface, as shown in Fig. 1. Before the 13C MRS experiment, the first-order shim coil currents were automatically adjusted by a proton phase image. The parameters for 13C MRS were TR 500 ms, observation bandwidth 8 kHz, sampling points 512 and number of data acquisitions 512. Twenty-four dummy scans were performed to achieve a steady state of magnetization. A CHESS pulse was used to suppress multiple signals of methanol –13CH3, with a bandwidth of 400 Hz, flip angle of 150° and center frequency of 49 ppm. The flip angle was calculated by the total signal intensity received by the surface coil. To apply the SAT pulse over the slab including the oil component case with 13C resonance frequencies, a proton MR image was used for localization, and the center frequency was changed from the proton resonance to that of 13C at 82 ppm automatically (Fig. 1). The RF power to achieve maximum fat suppression was obtained for each of SAT and CHESS.

Spectral analysis to quantify each 13C peak was performed using the SA/GE software package (GE Healthcare) on a workstation (IRIX O2, Silicon Graphics, Mountain View, CA). The averaged FIDs were processed with a 10 Hz exponential window function, zero-filled to double the sampling points, fast Fourier transformed, manually phase corrected, and cubic spline baseline correction was applied.

Results

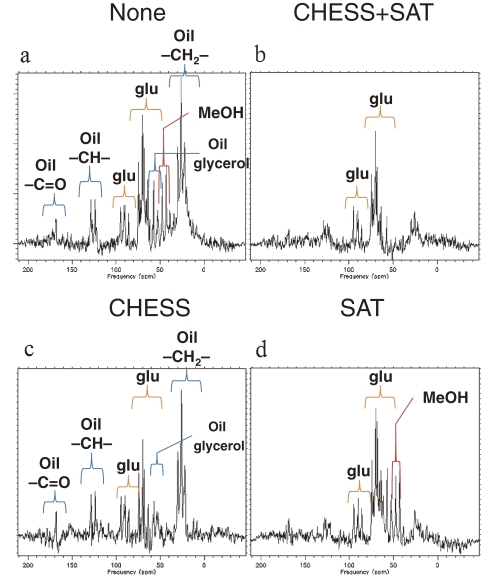

Figure 2 shows the 13C MR spectra obtained from the phantom with or without CHESS and SAT sequences. Table 1 shows the relative heights of each peak with both and without either sequence. Signal assignments of the oil were based on references.12–15) The reduction rate of 7 out of 8 peaks with both suppression pulses showed good agreement with the sum of separate SAT/CHESS pulses. With the combination of SAT and CHESS pulses, the residual rate of the oil carbonyl carbon peak (C=O, 168 ppm) was 40% of that without fat suppression (60% reduction), however, it was 83% (only 17% reduction) with SAT alone. The height percentages of the glucose C1β peak compared with the sum of all other peaks without and with the two suppression sequences were 21.8% and 33.4%, respectively, leading to a 53% increase in the relative scale of the glucose signal. With the CHESS pulse, the methanol –CH3 peaks centering around 49 ppm were suppressed to the residual rate of 13%. With additional removal of non-methanol –CH3 peaks by SAT pulse, the total signal was just 5% (95% reduction). Simultaneously, CHESS suppressed the signals originating from glucose C6 and/or glycerol (58 ppm) to 56%. Lipid signals from the oil component at various frequencies (26, 128 and 168 ppm) were decreased with SAT, especially reducing the –CH2– signals (26 ppm) to 18% (reduction rate of 82%). Glucose signals of C3 and C5 (70 ppm) might have been reduced by the CHESS pulse, since the excitation profile of CHESS was not strictly rectangular. Glucose signals ranging over 70 to 95 ppm were not affected by either of the fat suppression pulses.

Figure 2.

The 13C MR spectra of the phantom. The 13C MR spectra of the methanol, glucose and oil phantoms. The scale of vertical axes is arbitrary unit. Signals from methanol and lipid were observed in a wide range of chemical shift without CHESS and SAT pulses (2a). For example, spectral quantification analysis using SA/GE indicated that signal residue of the carbonyl carbon at 168 ppm was 40% with CHESS and SAT pulses (2b). The methanol signals around 49 ppm were suppressed with the CHESS pulse (2c). The lipid signals at various frequencies (26 (CH2), 128 (CH) and 168 ppm (C=O)) were well suppressed by the SAT pulse (2d).

Table 1.

Relative signal intensities (residual rate) of the 13C spectra

| Phantom component | Glucose | Glucose | Glucose | Glucose/Oil | Methanol | Oil | Oil | Oil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon group | C1α | C1β | C3/C5 | C6/glycerol | CH3 | CH2 | CH | C=O |

| Chemical shifts (ppm) | 90 | 96 | 70 | 58 | 49 | 26 | 128 | 168 |

| CHESS and SAT (%) | 100 | 86 | 87 | 44 | 5 | 19 | 53 | 40 |

| CHESS (%) | 96 | 100 | 77 | 56 | 13 | 90 | 95 | 98 |

| SAT (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 87 | 18 | 49 | 83 |

Each peak was obtained by applying Fourier transformation to the average of 1024 FIDs. The baseline (100%) was obtained by using the highest peak induced by J couplings without the two fat suppression pulse sequences. The chemical shifts (ppm) were observed in this experiment and their assignments were based on the references12,13,14,15) (see Fig. 2).

Discussion and conclusions

It was demonstrated that 13C fat signals could be most effectively suppressed in vitro by the combination of SAT and CHESS pulses, which reduce the signals of both subcutaneous and visceral fat. The optimum TR value for the best fat suppression condition and better detection of the target metabolite depends on their relaxation times. Since longer TR increases the total scan time, shorter TR will be practical for clinical usage, however, shorter TR reduces the detectability of glucose or low molecular weight metabolites with longer T1 than those of fat components. It was reported that in vivo and in vitro T1 relaxation times of [1-13C] liver glycogen were 150–170 ms16,17) at 4.7 T, while those of in vivo human fat at 1.9 T were within 500 ms or longer18) in rat at 2.0 T, except for the carbonyl carbons (1.94 s).19) Based on the T1 of glycogen in these reports, we chose TR of 500 ms in this study. Further optimization of TR for glycogen monitoring should be conducted using an in vivo model.

Another factor to reduce fat suppression is chemical shift displacement (CSD) of off-resonance signals induced by the field gradient in SAT. The signals of the metabolites contained in an organ are partially displaced into the volume selected for SAT, while some of those in the volume escape irradiation. This CSD problem is potentially not negligible, especially in 13C MRS, since the chemical shift range (approximately 220 ppm) is wide, while that of protons is 10 ppm. A practical method to minimize the CSD is to set the center frequency of SAT on the chemical shift of the most interest. In this study, the CSD of glucose 13C1β (96 ppm) was 1.9 mm with a field gradient strength of 2.21 gauss/cm, which was less than the gap (4.0 mm) among the components (Fig. 1), suggesting that the glucose signal was not strongly suppressed by the SAT pulse.

This CSD depends on the slice thickness of SAT. In order to avoid a significant effect of CSD, slice (slab) thickness of SAT should be optimized depending not only on the extent of CSD of the target signals but also on the anatomical (spatial) distance between the visceral fat and the tissue of interest obtained by the proton MR image. By arranging the gradient direction, the off-resonance signals of the metabolites can be shifted to the opposite side of the selected slice, leaving some signals out of the irradiated volume. When the peaks of interest are close to the lipid signals in frequency, the irradiation bandwidth of the CHESS pulses needs to be further optimized based on their excitation profile. Increasing the number of CHESS pulses, such as a triple CHESS pulse set frequently used in 1H-MRS, will achieve more lipid signal suppression, however, it will not be an effective solution for 13C-MRS, since it is difficult to safely cover the chemical shift range of lipid components widely distributed over the 200 ppm scale. Furthermore, it demands longer TR, resulting in a longer data acquisition time. Thus, we propose the combination pulse technique of a single CHESS pulse to suppress the main part of lipid peaks close to the glucose signal and a SAT pulse to spatially suppress the main part of fat tissue close to the surface coil.

One explanation for the discrepancy of the carbonyl signal reduction rate between the SAT pulse alone and the combination of SAT and CHESS pulses may be the pulse profile instability due to interference. The carbonyl carbon (168 ppm) of the oil is configured to be suppressed by the SAT pulse. The excitation profile in the frequency domain by the SAT pulse was close to rectanglular and its bandwidth was ±3000 Hz with a center frequency of 82 ppm. The 13C hard pulse to obtain 13C FID signal has a sinc shaped profile with a bandwidth of ±4000 Hz with the same center frequency. The carbonyl carbon was in the 2770 Hz lower field from the center frequency, and the location was near the ends in both profiles. Since the methanol signal was within the suppression range of the CHESS pulse in the frequency domain, it was reasonable that most of the signal intensity was reduced (residual rate 13%). On the other hand, SAT pulse partially decreased the methanol signal (residual rate 87%), although the signal source was spatially out of the SAT suppression range. One possible explanation is spatial extension of the suppression profile by the side lobes, although it cannot be verified in this experiment design. The methanol component will not be the major factor in this contamination, since the CSD was calculated to be 4.5 mm and the inter-space between the components was 4.0 mm.

In conclusion, the potential advantage of combining two kinds of lipid suppression pulses for in vivo 13C-MRS was demonstrated in this phantom study. As a future direction, the suppression profiles of the chemical shift domain by these two types of pulses should be further customized based on the in vivo 13C peaks of interest. To achieve further improvements to extract the highest glucose peak (C1β) using this combined pulse method, the relaxation times in an in vivo environment, which are different from those in vitro, will be the main point to be considered.

References

- 1).Beckmann N., Seelig J., Wick H. (1990) Analysis of glycogen storage disease by in vivo 13C NMR: comparison of normal volunteers with a patient. Magn. Reson. Med. 16, 150–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Roser W., Beckmann N., Wiesmann U., Seelig J. (1996) Absolute quantification of the hepatic glycogen content in a patient with glycogen storage disease by 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Imaging 14, 1217–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Fluck C.E., Slotboom J., Nuoffer J.M., Kreis R., Boesch C., Mullis P.E. (2003) Normal hepatic glycogen storage after fasting and feeding in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 4, 70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Krssak M., Brehm A., Bernroider E., Anderwald C., Nowotny P., Dalla Man C., Cobelli C., Cline G.W., Shulman G.I., Waldhäusl W., Roden M. (2004) Alterations in postprandial hepatic glycogen metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 53, 3048–3056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Ordidge R.J., Connelly A., Lohman J.A.B. (1986) Image-selected in vivo spectroscopy (ISIS). A new technique for spatially selective NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 66, 283–294 [Google Scholar]

- 6).Doddrell D.D., Galloway G.J., Brooks W.M., Bulsing J.M., Field J.C., Irving M.G., Baddeley H. (1986) The utilization of two frequency-shifted sinc pulses for performing volume-selected in vivo NMR spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 3, 970–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Choi I.Y., Tkáč I., Gruetter R. (2000) Single-shot, three-dimensional “non-echo” localization method for in vivo NMR spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 44, 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Cunnane S.C., Williams S.C., Bell J.D., Brookes S., Craig K., Iles R.A., Crawford M.A. (1994) Utilization of uniformly labeled 13C-polyunsaturated fatty acids in the synthesis of long-chain fatty acids and cholesterol accumulating in the neonatal rat brain. J. Neurochem. 62, 2429–2436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Haase A., Frahm J., Hänicke W., Mattaei D. (1985) 1H NMR chemical shift selective (CHESS) imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 30, 341–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Pauly J.M., Le Roux P., Nishimura D.G., Macovski A. (1991) Parameter relations for the Shinnar–Le Roux selective excitation pulse design algorithm. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 10, 53–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Ikonomidou V.N., Sergiadis G.D. (2000) Improved Shinnar–Le Roux algorithm. J. Magn. Reson. 143, 30–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Künnecke B., Küstermann E., Seelig J. (2000) Simultaneous in vivo monitoring of hepatic glucose and glucose-6-phosphate by 13C-NMR spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 44, 556–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Hwang J.-H., Bluml S., Leaf A., Ross B.D. (2003) In vivo characterization of fatty acids in human adipose tissue using natural abundance 1H decoupled 13C MRS at 1.5 T: clinical applications to dietary therapy. NMR Biomed. 16, 160–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Thomas E.L., Frost G., Barnard M.L., Bryant D.J., Taylor-Robinson S.D., Simbrunner J., Coutts G.A., Burl M., Bloom S.R., Sales K.D., Bell J.D. (1996) An in vivo 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopic study of the relationship between diet and adipose tissue composition. Lipids 31, 145–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Gottlieb H.E., Kotlyar V., Nudelman A. (1997) NMR chemical shifts of common laboratory solvents as trace impurities. J. Org. Chem. 62, 7512–7515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Zang L.H., Laughlin M.R., Rothman D.L., Shulman R.G. (1990) Carbon-13 NMR relaxation times of hepatic glycogen in vitro and in vivo. Biochemistry 29, 6815–6820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Overloop K., Vanstapel F., Van Hecke P. (1996) 13C-NMR relaxation in glycogen. Magn. Reson. Med. 36, 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Fan T.W.M., Clifford A.J., Higashi R.M. (1994) In vivo 13C NMR analysis of acyl chain composition and organization of perirenal triacylglycerides in rats fed vegetable and fish oils. J. Lipid Res. 35, 678–689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Moonen C.T.W., Dimand R.J., Cox K.L. (1988) The noninvasive determination of linoleic acid content of human adipose tissue by natural abundance carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance. Magn. Reson. Med. 6, 140–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]