Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this double-blind, placebo controlled exploratory pilot study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of risperidone for the treatment of anorexia nervosa (AN). Method: Forty females ages 12–21 (mean 16) years, with primary AN in an eating disorders program were randomized to receive risperidone (R, N=18) or placebo (PL, N=22). Subjects completed the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI-2), Color-A-Person Test, Body Image Software and Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children at baseline and regular intervals. Weight, labs, and ECG were monitored. Study medication was started at 0.5 mg daily and titrated upward weekly in 0.5 mg increments to a maximum dose of 4 mg until the subject reached a study end point. Results: Mean dose for the risperidone group was 2.5 mg and in the Placebo group 3 mg, for a mean duration of 9 weeks. R subjects had a significant decrease on the EDI-2 "Drive for Thinness" subscale over the first 7 weeks (p=0.002, effect size 0.88), but this difference was not sustained to study end (p=0.13). The EDI-2 "Interpersonal Distrust" subscale decreased significantly more in R subjects (p=0.03, effect size 0.60). R subjects had increased prolactin levels (week 7, p=0.001). There were no significant differences between groups at baseline or study end for the other rating scales, change in weight or laboratory measures. Conclusions: This study does not demonstrate a benefit for the addition of risperidone in adolescents with AN during the weight restoration phase of care.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, adolescents, risperidone, neuroleptics, psychopharmacology

Introduction

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) is a complex psychiatric disorder characterized by weight loss, body image distortion, fear of weight gain and loss of menses. 1 The common onset of AN during adolescence and high predominance of females suggest neurobiological and genetic factors may contribute to the pathophysiology of AN in addition to psychological and environmental factors. 2 There are no psychotropic medications approved for the treatment of AN in adults or adolescents. Most medication studies were case reports or open label trials, while placebo controlled trials to date have yielded neutral or negative results. 3–9 The lack of medications for the core symptoms of AN, combined with early promising findings from case reports and open label studies of atypical neuroleptics, led to increased use of these medications over the past decade, despite the lack of studies demonstrating efficacy. 10–18 “Atypical” neuroleptics, like risperidone and olanzapine, are potent 5HT2A (serotonin) antagonists, in addition to binding to dopamine 2 and 4 receptor sites.19 The open studies suggested that atypical neuroleptics were generally well tolerated by subjects and were associated with improvement in psychological factors that made it easier to treat such patients. There have been two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of olanzapine for AN in adult female subjects. One (N = 34) found an increased rate of weight gain and reduction in obsession scores. 20 The second RCT, which included a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) arm (N = 30) found no differences in change in weight, but improvement in compulsivity, depression and aggressiveness for the CBT + olanzapine group. 21 Subjective clinical experience and a retrospective chart review 22 prior to this double blind study suggested that some patients who were observed to have substantial difficulty with weight restoration, seemed to have less body image distortion and anxiety about food and weight when treated with risperidone.

The aim of this double-blind, placebo controlled exploratory pilot study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of risperidone for the treatment of adolescents and young adults with anorexia nervosa (AN) during the weight restoration phase of care. The primary exploratory hypothesis of the study was that subjects on risperidone would show a more significant decrease in drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction and body image distortion as compared to subjects on placebo. A secondary exploratory aim of the study was to determine if risperidone was an effective mediator in shortening the length of time it takes for a patient with AN to reach 90% of Ideal Body Weight (IBW). The study also sought to explore if risperidone could be safely administered to and tolerated by patients with AN, and if risperidone decreased anxiety symptoms during weight restoration.

METHOD

Subjects

All patients receiving care in the eating disorders program where the study was conducted during the study period (August 2004 to September 2008) who met inclusion criteria were offered the opportunity to participate. Informed consent for the IRB approved protocol was obtained from subjects 18 and older, parents of subjects under age 18, and informed assent from subjects under 18. Inclusion criteria included a primary diagnosis of AN, female gender, age 12–21 years and active in a level of care in the eating disorders program. Co-morbid diagnoses (depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, anxiety disorder, bulimia nervosa) were allowed as long as there was a primary diagnosis of AN. A diagnosis of AN was determined using DSM IV criteria by comprehensive clinical evaluation and concurrence of diagnosis by a child and adolescent psychiatrist (JH) and a specialist in adolescent medicine (ES). Initial clinical evaluation included a physical exam, psychiatric interview, interview with parents and a nutrition assessment by a registered dietician. Exclusion criteria were: previous enrollment in the study, allergic reaction to risperidone or another atypical neuroleptic, positive pregnancy test, taking a psychotropic medication other than an antidepressant, active hepatic or renal disease, males and wards of the court. Subjects were limited to females to minimize heterogeneity in the sample. Subjects were screened for sexual activity by an adolescent medicine physician. Subjects having vaginal intercourse were required to use birth control during the study and have a monthly urine pregnancy test.

The program in which the study occurred provides family centered care with an emphasis on parents taking charge of meal planning and supervision. All subjects were initially admitted into the inpatient or day treatment level of care (LOC) and received care as usual during the study, which included individual, family and group psychotherapies, nutrition consultation, medical management and individualized meal plans for weight restoration. The program targeted 90% of ideal body weight (IBW) for subjects with secondary amenorrhea and 100% IBW for subjects with primary amenorrhea. These target weights were based on research on normalization of menstruation in AN.23 Target weight was calculated for each subject based on the CDC norms for BMI at the 50th percentile based on gender, age and height24. Targeted rate of weight gain in the inpatient LOC was 0.2 kg per day and in day treatment 0.1 kg per day.

Despite the lack of demonstrated efficacy for antidepressants in AN, 3, 5, 7, 8 a significant number of patients present for treatment of AN on an antidepressant, typically a serotonin selective re-uptake inhibitor. Although it would have been ideal to have subjects take only the study medication, for reasons related to adequate subject recruitment it was decided to allow patients who were already taking an antidepressant medication to enroll in the study and continue their antidepressant if they were on a stable dose for more than 1 week prior to entering the study and did not wish to discontinue the medication. No dose adjustments were made to antidepressants during the study. No new psychotropic medications were allowed to be started after beginning the study medication. Subjects were allowed to take a multivitamin, zinc and medications for other medical conditions during the study, such as constipation, asthma and gastritis.

Procedures

Two randomization lists were created using PROC PLAN in SAS, one list for patients on antidepressants and the other for those not on antidepressants. On each list, the patient’s name was entered by the pharmacy alongside the next allocated treatment group. A block size of 4 was used to balance treatment assignment. Both the investigator and the patient were blinded as to treatment allocation and placebo medication was formulated to be indistinguishable from risperidone.

After consent/assent was obtained, subjects were randomized, completed baseline assessment measures and were started on 0.5 mg of the study medication, which was titrated upward weekly in 0.5 mg increments, until the subject reached a study end point, or a maximum of 4.0 mg of study medication. Compliance was monitored through pill counts and parent and patient reporting at study visits. There were 5 possible study end points. End Point 1 was based on reaching the target weight and maintaining at or above that weight for one month. The four other study endpoints were: worsening AN symptoms accompanied by two weeks of weight loss or failure to gain weight; medical complications or side effects; subject request to withdraw; and reaching maximum titration dose of 4 mg but not consistently gaining weight over a 4 week period of time.

Subjects completed weekly study visits for medication adjustment, measurement of vital signs and ratings of any physical complaints or side effects. All medications taken during the study were monitored and tracked at each study visit. Forty-five percent (18/40) of subjects were not from the state where the treatment center was located. There were 396 study visits, of which 341 (86%) were conducted at the study site and 55 (14%) completed by subjects who returned rating scales by mail and had physical data collected by their primary care provider. The PI had weekly phone contact with subjects who were not able to return for data collection after discharge. Study medication was mailed by the research pharmacy to subjects who returned to locations outside the state of the treatment center, and packets were returned by mail for pill counts.

Measures

Eating Disorder Inventory-Version 2 (EDI-2)25: The EDI-2 is a widely used 91 item self report measure of symptoms commonly associated with AN and Bulimia Nervosa which scores into 8 subscales and 3 provisional subscales. This study focused on the Drive for Thinness (EDI-2 DT) and Body Dissatisfaction (EDI-2 BD) subscales. This was completed at baseline, after 3 weeks on study medication and at subsequent 4 week intervals.

Body Image Software Program (BIS) 26: The BIS is a computer program that measures body size distortion and body dissatisfaction. A digital image is taken of the subject and using the BIS program the subject adjusts the image during 3 different tasks. In the method of Adjustment task (ADJ-Current), the subject adjusts the image wider or thinner to match their perceived current size. In a second Adjustment task, (ADJ-Desired) the subject adjusts the image to their “desired size”, with the discrepancy between the perceived and desired size being used as a measure of body dissatisfaction. In a third BIS task, using the adaptive probit estimation procedure (APE), subjects judged whether a series of static images of their body were distorted too wide or too thin. Analysis of the responses permits a determination of the “Point of Subjective Equality” (PSE) and difference limens (DL) values. The PSE reflects subjective judgment of body size and the DL reflects the amount of body size distortion necessary for the participant to detect the distortion 50% of the time. This was completed at baseline, after 3 weeks on study medication and at subsequent 4 week intervals.

Color-A-Person-Test (CAPT)27: The CAPT, used to assess body image dissatisfaction, consists of a frontal and side outline of an adolescent female figure, which subjects color using five colors corresponding to “very satisfied, satisfied, neutral, dissatisfied or very dissatisfied”. The result is scored by using an overlapping template which divides the body into 30 areas. An overall body dissatisfaction score is calculated as the mean of all the color score of the 30 areas, resulting in a range of 1–5. A score of 1 indicates “very satisfied” and increasing scores indicate dissatisfaction. This was completed at baseline, after 3 weeks on study medication and at subsequent 4 week intervals.

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC).28 The MASC is a 39 item self-report measure which assesses a range of common anxiety symptoms, rated on a 4-point scale from 1 (never true about me) to 4 (often true about me). This was completed at baseline, after 3 weeks on study medication and at subsequent 4 week intervals.

Resting Energy Expenditure (REE) was measured to determine if risperidone had an effect on body metabolism as the mediator of weight gain. Following an overnight fast, subjects rested for 30 minutes in a dimly lit room in the supine position. Resting metabolic rate was measured via indirect calorimetry (Sensormedics 2900 metabolic cart). Gas was collected under a ventilated plexiglass hood for 25 min, with the first 5 min of data, and any other period of non-steady state measurement, discarded. REE was assessed at baseline and study end, or week 11, whichever occurred first.

The Simpson-Angus Scale (SAS)29 and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) 30 were administered weekly to asses for extra pyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia.

Safety measures: electrocardiograms, liver enzymes, glucose, triglycerides, cholesterol, and prolactin were measured at baseline and week 7, 11 and subsequent 4 week intervals during study participation.

Data Analysis and Sample Size

The study was powered with a sample size of 25 patients per group to have 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.81 on any one of the three primary outcome scales, using a two-group t-test, assuming a 5% two-sided significance level. The data was analyzed as an Intent to Treat analysis according to the treatment group assigned at randomization. No adjustment was made for multiple testing as this was an exploratory pilot study. Data analysis was performed using SAS V9.2 (Cary, NC). Continuous variables were compared with a t-test and categorical variables were compared using a chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate, at baseline, for changes between baseline and week 7 (for safety parameters) and for reasons for ending the study. To take into account the correlation between observations in this longitudinal study, a mixed effects model was used to compare the groups over time including all data from all visits which subjects completed, and including baseline assessments for subjects who withdrew from the study within 3 days of starting the study drug. The time variable was week in study and the outcomes examined in separate models were %IBW, BMI, EDI-2 subscales, CAPT total score and subscales, BIS tasks and MASC total score and subscales. Each outcome and treatment group was tested for whether a quadratic or linear model was the best fit to the data and the final model chosen according to the test statistics. Effect sizes were calculated from the mixed effect model contrast t-value for differences in changes over time at week 7 and week 11 as (2*t/√d.f.) and for REE at study end using Cohen’s d as the difference in means/SD. Time to reaching End Point 1 was analyzed using a logrank test.

Results

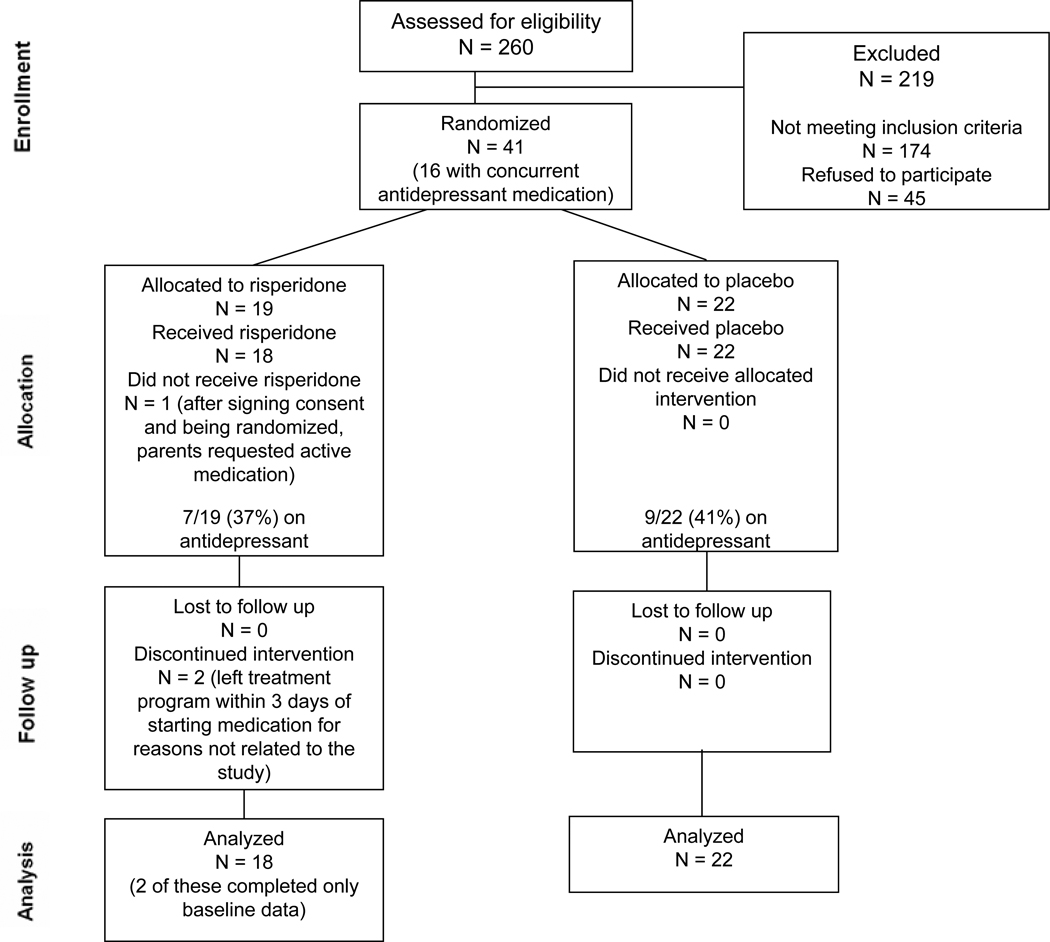

Of the 86 eligible subjects, 41 (48%) consented to participate in the double blind study (Figure 1). Subjects who refused participation primarily did not want to take any medication and did not differ by age, weight or antidepressant medication status. For subjects on an antidepressant (n=16) the median time on antidepressant prior to being randomized into the study was 11 weeks (range 1 week to 6 years). Only 3 patients had been on an antidepressant for less than 6 weeks when they started the study drug. 40 subjects started the study medication. Two subjects completed baseline measures but elected to discharge from the treatment program within 3 days of starting the study medication, for reasons unrelated to the study, and returned to out-of state locations.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants

There was no significant difference in age, study medication dose, time on study medication, LOC, % IBW, BMI, REE or baseline rating scales (EDI-2 DT and BD, CAPT, BIS tasks, MASC) between the 2 groups (Table 1). Thirty of the subjects were under age 18. Mean age for those < 18 was 14.8 years.

Table 1.

Group differences at baseline

| Risperidone (N=18) | Placebo (N=22) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean, SD, range) | 16.2 yrs (2.5) (13–20) | 15.8 years (2.3) (12–21) | 0.65 |

| Study Medication dose (Mean, SD) | 2.5 mg (1.2) (range 0.5 to 4 mg) | 3.0 mg (1.0) (range 1.5 to 4 mg) | 0.20 |

| Time on study medication (Mean, SD) | 8.6 weeks (4.2) (range 0 to 17 weeks) (9.6 ± 3.0 weeks for those 16 subjects in study >3 days) |

9.3 weeks (3.2) (range 3 to 18 weeks) |

0.52 |

| LOC while on study medication (Mean days, SD) | Inpatient 17.3 (14.5) | Inpatient 15.1 (11.2) | 0.62 |

| Day Treatment 23.8 (11.9) | Day Treatment 23.2 (11.1) | 0.88 | |

| Intensive Outpatient 26.4 (30.6) | Intensive Outpatient 15.8 (12.8) | 0.54 | |

| Outpatient 28.7 (18.1) | Outpatient 43.2 (25.5) | 0.10 | |

| Total 59.3 (21.7) | Total 63.6 (23.0) | 0.61 | |

| % IBW at baseline | 77.7% (4.7) | 79.1% (3.8) | 0.30 |

| BMI at baseline | 15.9 (1.0) | 16.1 (1.3) | 0.54 |

| REE at baseline | 1096 (183) | 1070 (118) | 0.60 |

| EDI-2 DT at baseline | 15.8 (4.6) | 12.5 (7.8) | 0.11 |

| EDI-2 BD baseline | 17.5 (6.7) | 15.4 (9.8) | 0.44 |

| MASC-Total at baseline | 62.9 (19.6) | 61.5 (13.8) | 0.80 |

| CAPT-Total at baseline | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.8) | 0.21 |

| BIS–PSE at baseline | 9.3 (8.1) | 9.2 (12.1) | 0.99 |

| BIS-DL at baseline | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.7) | 0.76 |

| ADJ-current at baseline | 11.4 (11.6) | 10.9 (15.4) | 0.90 |

| ADJ-desired at baseline | −10.3 (9.3) | −4.4 (11.4) | 0.24 |

Note: Group differences at baseline for mean age, medication dose, time on study medication, Level of Care (LOC), percent Ideal Body Weight (% IBW), Body Mass Index (BMI) and Resting Energy Expenditure (REE). Rating scales: Eating Disorder Inventory 2 (EDI-2); Drive for Thinness (EDI-2 DT) and Body Dissatisfaction (EDI-2 BD), Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC), Color-a-Person Test (CAPT), Body Image Software (BIS), Point of Subjective Equality (PSE), Difference Limens (DL), Adjustment-Current (ADJ-current) and Adjustment Desired (ADJ-desired)

The first exploratory hypothesis was that subjects on risperidone would have a greater decrease in the drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction and body image distortion than subjects on placebo. This exploratory hypothesis was partially supported. From the mixed effect model, there was a significant difference for the EDI-2 DT subscale; R subjects had a significant decrease over the first 7 weeks (t-value for difference between treatments in change from baseline to 7 weeks = 3.25 with 54 d.f., effect size 0.88, p=0.002), but this difference was not sustained to week 11 (t-value=1.55 with 54 d.f., effect size 0.42, p=0.13). EDI-2 DT did not significantly change over time for PL subjects. There were no other significant differences between R and PL in change over time for measures of body dissatisfaction (change from baseline to 7 weeks, R vs. PL: EDI-2 BD, effect size 0.52, p=0.06, CAPT, effect size 0.40, p=0.16, BIS ADJ-desired, effect size 0.42, p=0.35), or body image distortion (BIS-PSE, effect size 0.34, p=0.29, BIS-DL, effect size 0.59, p=0.08, BIS ADJ- current, effect size 0.05, p=0.87). There were no significant changes between R and PL in change over time for anxiety as measured by the MASC (effect size 0.21, p=0.44). There was an unexpected finding on the EDI-2 subscale “Interpersonal Distrust” (EDI-2 ID); R subjects had a significantly greater decrease than PL subjects (t-value for difference in change from baseline = 2.22 with 54 d.f., effect size 0.60, p=0.03).

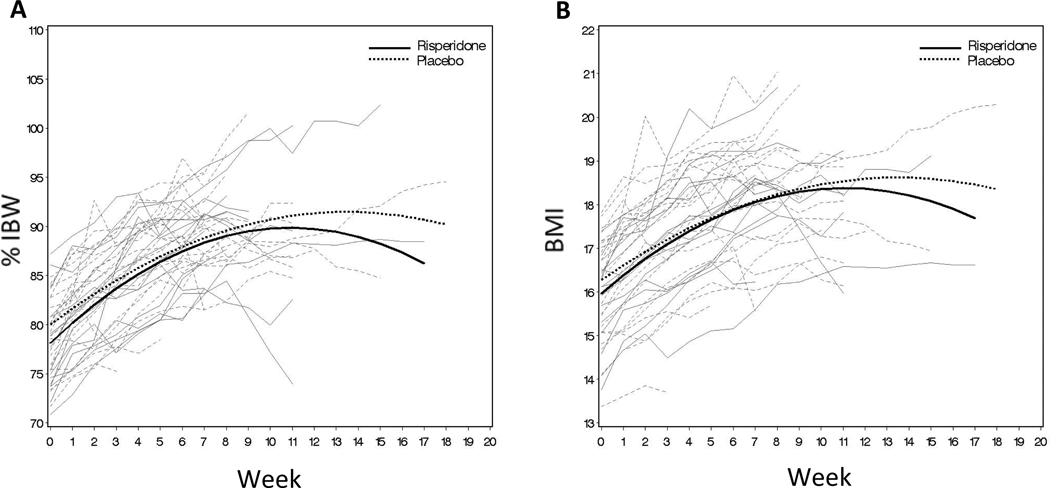

The second exploratory aim of the study was to determine if risperidone was an effective mediator in shortening the length of time it takes a subject with AN to reach 90% of IBW. Initially, we hypothesized that risperidone would shorten the length of time to reach target weight, and that this effect may be mediated by decreased body metabolism (measured by REE). Not only were there no significant differences between R and PL for change in %IBW and BMI over the period of the study (Figure 2), there was no evidence that subjects on R had a decrease in body metabolism. In fact, at study end, subjects on R had a non-statistically significant mean increase in REE compared to subjects on PL (increase for R=73 (SD 185), n=10; vs. PL 12 (SD 110), n=13, effect size 0.41, p=0.34). There were no significant differences in proportions of patients reaching study end points (p=0.72, Table 2), weeks in study by each end point or the time to reach End Point 1 (p=0.76) between R and PL. Thus, the second exploratory hypothesis was not supported.

Figure 2.

A: Observed subjects percent of ideal body weight (%IBW) by week of visit (shown in gray) and estimated mean %IBW at each week across all subjects (shown in black). B: Observed subjects body mass index (BMI) by week of visit (shown in gray) and estimated mean BMI at each week across all subjects (shown in black).

Table 2.

Mean weeks in study by study end point

| Risperidone (R) (N=18) | Placebo (PL) (N=22) | p-value for number of weeks in study for each end point, R vs. PL |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Mean weeks in study (SD) |

N (%) | Mean weeks in study (SD) |

||

| Reach target weight and maintain for 1 month | 6 (33%) | 10.0 (2.7) | 10 (45%) | 9.5 (3.3) | 0.76 |

| Worsening anorexia nervosa symptoms and 2 weeks of weight loss | 2 (11%) | 9.0 (2.8) | 3 (14%) | 6.7 (3.5) | 0.50 |

| Medical complications or side effects | 1 (6%) | 9.0 | 0 | N/A | |

| Patient request to end study | 7 (39%) | 5.6 (4.1) | 6 (27%) | 8.7 (2.4) | 0.14 |

| At maximum titration dose for 4 weeks without consistent weight gain | 2 (11%) | 14.0 (4.2) | 3 (14%) | 12.7 (2.1) | 0.66 |

Orthostatic blood pressure and pulse, ECG, triglycerides, cholesterol, liver enzymes and glucose showed no significant differences between groups during the study (Table 3). Prolactin levels were significantly increased for R at week 7 and for subjects who were in the study through week 11 (R prolactin 37.7 ng/ml (SD 36.2) vs. PL prolactin 5.5 ng/ml (SD 1.6), p=0.001). Total reported physical complaints were similar between the 2 groups, R=146, PL=143. Physical complaints more frequently reported in the R group were fatigue (39 vs. 22) and dizziness (15 vs. 4). PL subjects reported more gastrointestinal complaints (53 vs. 35) and headache (8 vs. 5). Psychiatric symptoms reported more frequently in the R group were depression (2 vs.0) and suicidal ideation (4 vs.0), while the PL group reported more anxiety (6 vs. 1) and insomnia (4 vs. 0). There were no significant differences between groups on the SAS or AIMS rating scales, with 8 subjects in each group having a SAS score > 0, and 5 R subjects vs. 1 PL subject scoring > 0 on the AIMS (p=0.06). There were no Significant Adverse Event’s during the study.

Table 3.

Labs, Electrocardiogram (ECG) and pulse (Mean (SD))

| Risperidone (R) | Placebo (PL) | p-value for change, R vs. PL |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline N=18 |

Week 7 N=15 |

Baseline N=22 |

Week 7 N=20 |

||

| Prolactin ng/ml | 15.4 (9.9) | 54.4 (36.4) | 13.7 (5.7) | 8.9 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Glucose mg/dl | 76.1 (11.7) | 83.7 (7.2) | 83.7a (11.4) | 82.1 (5.7) | 0.08 |

| Cholesterol mg/dl | 166.7 (28.3) | 172.5 (45.0) | 169.7 (29.0) | 157.8 (34.4) | 0.08 |

| Triglycerides mg/dl | 82.8 (55.4) | 75.3 (36.8) | 69.2 (20.2) | 65.8 (24.5) | 0.73 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (u/L) | 84.8 (48.5) | 88.7 (39.5) | 88.4 (51.9) | 95.8 (48.5) | 0.10 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) (u/L) | 24.6 (12.5) | 22.1 (6.0) | 23.1 (9.9) | 24.7 (10.5) | 0.27 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) (u/L) | 42.4 (15.9) | 37.9 (14.7) | 41.3 (21.1) | 41.1 (16.4) | 0.98 |

| ECG – rate | 56.1 (13.9) | 66.9 (9.6) | 57.3 (12.1) | 66.0 (15.6) | 0.43 |

| ECG -QTc | 401.4 (31.8) | 409.8 (21.3) | 399.6 (27.2) | 414.1 (23.5) | 0.20 |

| ECG -PR | 143 (21.3) | 139 (16.7) | 151.5 (20.1) | 141.4 (23.3) | 0.23 |

| Supine Pulse | 60.8 (18.8) | 69.9 (13.3) | 61.8 (13.0) | 66.6 (15.7) | 0.75 |

| Standing Pulse | 92.0 (17.9) | 91.3 (25.7) | 96.1 (21.4) | 85.1 (16.8) | 0.82 |

Note: QTc = corrected interval between start of Q and end of T wave.

Difference between Risperidone and Placebo for glucose at baseline was significant (p=0.04)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this exploratory study is the first randomized placebo controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of risperidone in the treatment of AN. The primary exploratory hypothesis of the study was that subjects on risperidone would show a significant decrease in drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction and body image distortion as compared to subjects on placebo. This study found a statistically significant decrease on the EDI-2 DT subscale for R subjects over the first 7 weeks, with an effect size of 0.88. However, this difference was not sustained to study end. Both subject groups continued to have clinically significant EDI-2 DT scores throughout the study. Risperidone did not significantly affect measures of body dissatisfaction, body image distortion or anxiety, despite moderate effect sizes for some of the rating scales in this small exploratory study.

A secondary exploratory aim of the study was to determine if risperidone was an effective mediator in shortening the length of time it takes for subjects with AN to reach and maintain a target weight and if risperidone had an effect on body metabolism, as measured by REE, as a mediator of weight gain. Surprisingly, not only did subjects on R not gain weight any faster than subjects on PL, but there was a trend for subjects on R to have an increase in REE, not a decrease. This finding needs to be replicated, but presents an interesting paradox. In many patients taking risperidone for other reasons, there is significant weight gain. Most consider this due to appetite increase and subsequent increase in food intake, but it is possible that risperidone affects body metabolic rate. We do not know if AN subjects on risperidone experienced increased appetite which they had to defend against in order to maintain their drive for thinness. With regard to measures of safety and tolerance, risperidone was well tolerated, other than elevated prolactin levels, which should be closely monitored in patients on risperidone, and no other lab or ECG abnormalities were found in either group.

In future studies, it may be important to evaluate participation in concomitant treatment, motivation for change and improved sleep as additional target outcomes. Although not part of the study hypotheses, there was a sustained significant decrease for subjects on risperidone on the EDI-2 Interpersonal Distrust subscale, which includes items primarily related to communication; being open about feelings, trusting others and expressing emotions, which warrants further exploration in future studies.

There are a number of limitations to the study. The investigators decided to end the study after 4 years due to slow recruitment typical of this subject pool and exhausted funding, although the results do not suggest that reaching the intended recruitment number of 50 would have changed the outcome. At the time of study termination, the sample size of 40 was larger than previously published randomized trials of atypical neuroleptics for AN. A sample size of 40 had 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.91 rather than the planned effect size of 0.81, but the study nevertheless was powered to detect clinically important differences. Enrollment was significantly impacted by the number of potential subjects who declined participation. Medication studies in AN have typically been challenged by slow and low enrollment as it is difficult to recruit and retain subjects with AN. 31, 32 Multi-site studies should be considered in this subject population whenever possible to improve recruitment numbers and length of time for study completion. Providers may also consider only prescribing psychotropic medications under a clinical research trial, similar to the oncologists, as a way of improving documentation of what is effective in this population. Subject retention was challenging, with 33% of subjects requesting to end the study before reaching their target weight. Halmi 32 comments that the high treatment refusal rates in AN leads to challenges in interpreting results as they may “apply only to AN patients who are willing to accept pharmacological and intensive day treatments that enhance weight gain, in other words, a minority of the AN population”. One effort to conduct a study of olanzapine in adolescents with AN 31 was closed due to inadequate enrollment, resulting in a publication of the many factors which impacted subject recruitment, including challenges related to inclusion criteria and 74% of eligible subjects declining participation primarily due to concerns about the study medication and research in general.

The study design also presented some limitations. While the design was built to replicate clinical practice with risperidone and focused on symptoms during weight restoration in subjects initially treated in higher levels of care, the study medication titration and length of time on study medication was based on weight trends and reaching target weight and contributed to variation in dosing and length of study participation. A study design with fixed medication titration and target doses for all subjects, independent of weight trends, might improve the ability to interpret the impact of the medication over time. It is also possible that the core symptoms of AN may require a longer period of time on an atypical neuroleptic, or a higher dose to remit or improve. Despite the lack of significant improvement based on the rating scales used in this study, most subjects showed significant and sustained improvement in BMI during the study. It is not clear what allowed subjects to maintain at a healthier weight while still experiencing drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction and anxiety, but it likely has to do with other therapeutic elements of the treatment intervention. The exclusion of male subjects limits the ability to generalize results to males with AN.

Another limitation of this study was the inclusion of subjects treated concurrently with an antidepressant. While accounted for with stratification during the randomization process, this may still have contributed to the results of the study, despite the fact that research has not established antidepressant medications to be beneficial for core symptoms of AN or co-morbid anxiety and depression in the context of AN.

Although there appear to be alterations in dopamine and serotonin transmission in the brain in AN, the psychopharmacological interventions currently available do not significantly impact treatment outcomes for patients with AN. Identifying neurobiological mechanisms that contribute to the development and maintenance of AN through genetic and neuroimaging methods may help identify more promising targets for pharmacologic interventions.

This exploratory pilot study does not demonstrate a clear benefit from the addition of risperidone in the course of active treatment and weight restoration in adolescents with AN. At this time, there is not sufficient evidence to support recommending atypical neuroleptics for the treatment of AN, and caution should be used when doing so. Further studies are required to more definitively evaluate the efficacy of atypical neuroleptics for AN. Based on current research, there are no empirically based effective treatments for adolescent AN. Family based interventions show the most promise for outpatient teenage AN patients who do not have lengthy durations of illness.33, 34

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Clinical Trials Research Center, Children’s Hospital Colorado (M01RR00069), an investigator-initiated grant from Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, for the study medication, placebo and subject compensation and a grant from the Developmental Psychobiology Endowment Fund, University of Colorado School of Medicine (JH)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Dr. Sigel receives research funding from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the Colorado Injury Control Research Center, and the University of Colorado School of Medicine Dean’s Academic Enrichment Fund. He has served on a speakers’ bureau for Merck Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Frank receives research support from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Davis Foundation Award of the Klarman Family Foundation Grants program in Eating Disorders. Dr. Wamboldt receives research support from Eli Lilly and Co., the National Institute of Mental Health, the American Psychiatric Association (APA), and has books and intellectual property with the American Lung Association and the APA Press. Drs. Hagman, Gralla, Gardner, and O’Lonergan, and Ms. Ellert, and Ms. Dodge report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Hagman, University of Colorado School Of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado

Jane Gralla, University of Colorado School Of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado

Eric Sigel, University of Colorado School Of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado

Swan Ellert, University of Colorado School Of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado

Mindy Dodge, Children’s Hospital Colorado. Dr. Gardner is with the University of Colorado, Denver

Rick Gardner, University of Colorado School Of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado

Teri O’Lonergan, University of Colorado School Of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado

Guido Frank, University of Colorado School Of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado

Marianne Z. Wamboldt, University of Colorado School Of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado

References

- 1.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulik CM. Exploring the gene-environment nexus in eating disorders. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005 Sep;30(5):335–339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Couturier J, Lock J. A review of medication use for children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Nov;16(4):173–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strober M, Freeman R, DeAntonio M, Lampert C, Diamond J. Does adjunctive fluoxetine influence the post-hospital course of restrictor-type anorexia nervosa? A 24-month prospective, longitudinal followup and comparison with historical controls. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(3):425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crow SJ, Mitchell JE, Roerig JD, Steffen K. What potential role is there for medication treatment in anorexia nervosa? Int J Eat Disord. 2009 Jan;42(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.20576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gwirtsman HE, Guze BH, Yager J, Gainsley B. Fluoxetine treatment of anorexia nervosa: an open clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990 Sep;51(9):378–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holtkamp K, Konrad K, Kaiser N, et al. A retrospective study of SSRI treatment in adolescent anorexia nervosa: insufficient evidence for efficacy. J Psychiatr Res. 2005 May;39(3):303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attia E, Haiman C, Walsh BT, Flater SR. Does fluoxetine augment the inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa? Am J Psychiatry. 1998 Apr;155(4):548–551. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martiadis V, Castaldo E, Monteleone P, Maj M. The role of psychopharmacology in the treamtent of eating disorder. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4(2):51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aragona M. Tolerability and efficacy of aripiprazole in a case of psychotic anorexia nervosa comorbid with epilepsy and chronic renal failure. Eat Weight Disord. 2007 Sep;12(3):e54–e57. doi: 10.1007/BF03327643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trunko ME, Schwartz TA, Duvvuri V, Kaye WH. Aripiprazole in anorexia nervosa and low-weight bulimia nervosa: Case reports. Int J Eat Disord. 2010 Feb 22; doi: 10.1002/eat.20807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boachie A, Goldfield GS, Spettigue W. Olanzapine use as an adjunctive treatment for hospitalized children with anorexia nervosa: case reports. Int J Eat Disord. 2003 Jan;33(1):98–103. doi: 10.1002/eat.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis K, Le Grange D, Bremer J. Olanzapine use in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2006 Jun;11(2):e53–e56. doi: 10.1007/BF03327760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ercan ES, Copkunol H, Cykoethlu S, Varan A. Olanzapine treatment of an adolescent girl with anorexia nervosa. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2003 Jul;18(5):401–403. doi: 10.1002/hup.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.La Via MC, Gray N, Kaye WH. Case reports of olanzapine treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2000 Apr;27(3):363–366. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200004)27:3<363::aid-eat16>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehler C, Wewetzer C, Schulze U, Warnke A, Theisen F, Dittmann RW. Olanzapine in children and adolescents with chronic anorexia nervosa. A study of five cases. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001 Jun;10(2):151–157. doi: 10.1007/s007870170039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman-Toker J. Risperidone in anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000 Aug;39(8):941–942. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200008000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powers PS, Santana CA, Bannon YS. Olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: an open label trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2002 Sep;32(2):146–154. doi: 10.1002/eat.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labellarte M, Riddle MA. Growing Up Whole: A focus on the use of atypical antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Quintiles Medical Communications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bissada H, Tasca GA, Barber AM, Bradwejn J. Olanzapine in the treatment of low body weight and obsessive thinking in women with anorexia nervosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Oct;165(10):1281–1288. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brambilla F, Garcia CS, Fassino S, et al. Olanzapine therapy in anorexia nervosa: psychobiological effects. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007 Jul;22(4):197–204. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328080ca31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carver A, Miller S. International Conference on Eating Disorders. Boston, MA: Academy of Eating Disorders; 2001. The use of risperidone for anorexia nervosa. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golden NH, Jacobson MS, Sterling WM, Hertz S. Treatment goal weight in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: use of BMI percentiles. Int J Eat Disord. 2008 May;41(4):301–306. doi: 10.1002/eat.20503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv. Data. 2000 Jun 8;314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garner DM. Eating Disorder Inventory-2: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardner RM, Boice R. A computer program for measuring body size distortion and body dissatisfaction. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004 Feb;36(1):89–95. doi: 10.3758/bf03195553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wooley OW, Roll S. The Color-A-Person Body Dissatisfaction Test: stability, internal consistency, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 1991 Jun;56(3):395–413. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5603_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.March J, editor. Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children. Tonawanda, NY: Multihealth Systems Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simpson GM, Lee JH, Zoubok B, Gardos G. A rating scale for tardive dyskinesia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1979 Aug 8;64(2):171–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00496058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munetz MR, Benjamin S. How to examine patients using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. Hosp. Community Psychiatry. 1988 Nov;39(11):1172–1177. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.11.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norris ML, Spettigue W, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N. Factors influencing research drug trials in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Eat Disord. 2010 May;18(3):210–217. doi: 10.1080/10640261003719468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halmi KA. The perplexities of conducting randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trials in anorexia nervosa patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Oct;165(10):1227–1228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08060957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lock J, Agras WS, Bryson S, Kraemer HC. A comparison of short- and long-term family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Jul;44(7):632–639. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000161647.82775.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lock J, Couturier J, Agras WS. Comparison of long-term outcomes in adolescents with anorexia nervosa treated with family therapy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006 Jun;45(6):666–672. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215152.61400.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]