Abstract

The large gap between intervention outcomes demonstrated in efficacy trials and the apparent ineffectiveness of these same programs in community settings has prompted investigators and practitioners to look closely at implementation fidelity. Critically important, but often overlooked, are the implementers who deliver evidence-based programs -- the effectiveness of programs cannot surpass skill levels of the people implementing them. This article distinguishes fidelity at the programmatic level from implementer fidelity. Two components of implementer fidelity are defined. Implementer adherence and competence are proposed to be related but unique constructs that can be reliably measured for training¸ monitoring, and outcomes research. Observational measures from a school-based preventive intervention are provided and the unique contributions of implementer adherence and competence are illustrated. Distinguishing implementer adherence to the manual and competence in program delivery is a critical next step in child mental health program implementation research.

Keywords: Fidelity, implementer skill, adherence, competence, observational methods, measurement

Introduction

It is widely recognized that prevention programs for children and families must have demonstrated efficacy through randomized control trials. A variety of sources (e.g., Blueprints; Mihalic & Irwin, 2003) list interventions proven to prevent or reduce mental health problems under tightly controlled conditions. The same outcomes, however, are frequently not evident when these programs are transported to community-based settings (Backer, 2000; Bumbarger & Perkins, 2008; Glasgow, Lichtenstein & Marcus, 2003; Spoth, Clair, Greenberg, Redmond & Shin, 2007). Clearly, the next phase for prevention research is the systematic study of factors that promote effective implementation and positive outcomes in the real world where children’s services are provided.

What accounts for the gap between intervention outcomes demonstrated in efficacy trials and the effectiveness of these same programs in community settings? The literature points to several implementation factors including readiness to implement an evidence-based program, adaptation and drift from the program model that occur in response to barriers and contextual factors, and weak pre-implementation training and lack of ongoing monitoring (Bumbarger & Perkins, 2008; Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Freidman & Wallace, 2005). Often overlooked, but critically important, is the fact that the effectiveness of programs in communities cannot surpass skill levels of the people implementing them (Cross, 2009). Thus, examining implementer behaviors is critical to understanding how evidence-based programs are actually delivered to children and families. This information is vital for interpreting lower-than-expected clinical outcomes. Without accurate measures of adherence associated with program and implementer implementation, and competence at the implementer level, Type III errors (Dobson & Cook, 1980) may occur. That is, conclusions about an intervention’s lack of outcomes will be erroneous if results reflect poor implementation at either level rather than a failure of theoretical or programmatic elements.

In this article, we first distinguish implementation fidelity at the program level from behaviors that comprise fidelity at the implementer level, and then focus on the latter. Implementer fidelity can be operationalized as: a) adherence to the intervention manual and, b) competence in program delivery. The rationale for, and benefits of, distinguishing these two components of implementer fidelity are discussed. Observational measures of implementer adherence and competence from a school-based preventive intervention are presented to illustrate each constructs’ potential unique contribution to understanding implementation.

Implementation fidelity: An overview

The term implementation fidelity generally refers to the degree to which a program is delivered as intended by the developers. There is, however, a tension in the literature between those who advocate strict fidelity to the original program and those who promote flexibility in adapting to community contexts. Simply stated, advocates of the former assert that the research evidence supports the program as it was delivered under specific conditions and that it should be implemented “with fidelity” in order to achieve the same outcomes. The latter proponents argue that adaptation of program elements, including implementation, is necessary to respond to contextual and cultural characteristics. Although we do not address the “fidelity-adaption” debate in this article (cf Backer, 2002; Hill, Maucione & Hood, 2007; Ringwalt, Ennett, Johnson, Rohrbach, Simons-Rudolph et al., 2003), we believe studies that measure implementer adherence and competence, as illustrated in this article, will contribute important data and elucidate the discussion.

As a broad construct, fidelity of implementation has been defined variously across studies which creates some confusion (Durlak & DuPre 2008; Dusenbury, Brannigan, Falco & Hansen, 2003; Forgatch, Patterson, & Degarmo, 2005; Frank, Coviak, Healy, Belsa & Casado, 200). One reason for the confusion is that the terms fidelity, ‘adherence’, and ‘competence’ have been used across programmatic implementation and interventionist implementation levels. At the programmatic level of implementation, investigators often consider adherence to the program delivery model as the measure of fidelity. This is also relevant at the individual level but the quality of how the intervention is delivered, which is reflected in the competence of the implementer, is also critical and can only be measured at the individual level. Moreover, because many interventions are transactional in nature, process variables are appropriately measured at the individual level. We will first describe adherence and competence broadly, and then focus on the rationale for and measurement of adherence and competence at the interventionist level.

At the programmatic level, adherence refers to the degree to which program implementation in the target setting is consistent with, or adherent to, the original implementation plan dictated by the developers. Program adherence, sometimes referred to as program fidelity, attends to elements, activities, and materials that differentiate it from other similar programs . For example, in the school-based prevention program, Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS; Greenberg, Kusche, Cook & Quamm, 1995), specific classroom lessons are to be presented three times a week by teachers. Implementation adherence at the PATHS program level is compromised if the lessons are not delivered by teachers or are conducted at a different rate, thereby altering the intervention “dosage.”

Program fidelity, or implementation adherence at the programmatic level, is typically measured by surveying program representatives or via site visits (Poduska, Kellam, Brown, Ford, Windham et al., 2009; Warren, Domitrovich & Greenberg, 2009). For example, Dariotis, Bumbarger, Duncan & Greeenberg (2008) sampled 32 evidence-based prevention programs and measured adherence to the implementation plan. Program representatives used a single-item to rate on a 4-point scale how closely to the original plan they felt their program was being delivered. As part of the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project, McHugo and colleagues (McHugo, Drake, Whitley, Bond, Campbell, Rapp et al., 2007) describe multi-item fidelity scales used by program site visitors. Sources of information included: interviews with team leaders and practitioners, observations of team meetings and of the intervention, interviews with program recipients, and chart reviews. A multimodal approach to assessment of program fidelity, such as the one conducted by McHugo et al., yields comprehensive, reliable information.

In large scale program dissemination, implementation adherence at the program level can inform researchers about the feasibility of translating an intervention to communities. If an intervention cannot be delivered accurately or fully in real-world settings, it may not be feasible as it was originally designed and may require modification. Assessment of adherence at the programmatic level also allows researchers to learn about the extent to which adaptation occurs.

At the individual implementer level, adherence refers to the degree to which the implementation agent delivers the content of the program as specified in the manual to the target person or group. In the treatment literature, this is referred to as intervention integrity (Flannery-Schroeder, 2005; Perepletchikova & Kazdin, 2005). When measured by objective behavioral markers, implementer adherence can be operationalized in terms of percent of the program delivered. For example, in the PATHS program, each lesson has specified content and activities that must be carried out; implementer adherence is the degree to which the teacher conducts the lesson as instructed in the manual. One teacher may deliver 90% of a specific lesson while another may deliver 30% of the same lesson, the former being more adherent. Competence, or quality of program delivery, is less likely than adherence to be assessed and reported in the literature. If it is considered, competence is typically measured at the individual implementer level in the context of treatment studies (e.g., Hogue, Henderson, Dauber, Barajas, Fried et al., 2008) rather than preventive interventions delivered by non-clinicians in communities.

Waltz, Addis, Koerner & Jacobson (1993) assert that an interventionist’s competence should be considered in the context of a specific program, “We move away from a notion of general therapeutic competence and focus instead on competence in performing a certain type of treatment.” (p. 621). The conceptualization of competence by Waltz and colleagues is particularly valuable for studies of manualized preventive interventions because most programs are not conducted in a rote manner. Unlike therapists, who are expected to develop general therapeutic skills across a variety of treatments, prevention interventionists are typically non-clinicians (e.g., teachers, coaches, paraprofessionals) trained to deliver a specific program. For example, teachers trained to deliver PATHS are not expected to be competent to deliver other mental health or preventive interventions. Moreover, it seems reasonable to expect that quality of program delivery is no less important when the implementers are non-clinicians.

Rationale for studying implementer adherence and competence

The rationale for examining interventionist behaviors can be summarized in three broad categories: outcome research, transporting programs to community settings, and training. We address each briefly.

Outcome research

Implementer adherence to program content is critically important for accurate conclusions of even the most rigorous outcome studies including randomized controlled trials (RCT). Variations in interventionist adherence or competence --or both-- may account for conflicting findings in the literature about a program’s effectiveness. Low levels of adherence to the manual content would compromise a test of an intervention. It would be inaccurate, for example, to conclude that Intervention X was effective, or ineffective, if implementers delivered content and techniques from Intervention Y, or a mix of Interventions X and Y along with a few elements from other programs. Although low implementer adherence indicates that the intervention is not fully delivered, strict adherence to a manual’s techniques or content may have consequences as well. There is evidence that very high adherence to some programs’ content actually may be associated with poorer outcomes (James, Blackburn, Milne, & Reichfelt, 2001). Evidence for establishing the level of adherence associated with positive outcomes is simply lacking for most programs. In addition, developers typically include a number of elements in an intervention based on theory. Once positive outcomes are demonstrated, questions arise regarding which elements of a program are necessary for an implementer to deliver in order to achieve those outcomes. As part of the deconstruction process of an intervention, knowledge about implementer adherence has the potential to provide important data about the active ingredients.

How might the quality or competence of implementer program delivery affect conclusions from outcome research on an intervention? One can imagine a situation where an implementer provides the content described in Intervention X’s manual, and thus demonstrates a high level of adherence, but does so in a manner that is not at all consistent with the developer’s expectations for delivery quality. For example, insensitivity to the individual or group receiving the program, as well as poorly timed or clumsily communicated content, would compromise the transactional nature of the process and thus clinical outcomes. It would be difficult to assert that a true test of the program has occurred under these conditions. The James et al. study (2001), in which a high level of adherence was associated with poor outcomes, did not assess competence which may have been low. Clearly, a low level of implementer competence is likely to confound interpretation of intervention outcome research.

Transporting programs to community settings

Evidence-based programs shown to prevent or reduce poor outcomes in children and families are destined for agencies, schools, and other community-based settings. Nevertheless, research has found a gap between outcomes from efficacy studies and the positive impact of the same programs implemented ‘on the ground.’ Implementation variability has been posited as one of the reasons for the difference (Bumbarger & Perkins, 2008; Fixsen et al., 2005; Hutchings, Bywater, Eames & Martin, 2008). Rigorous studies of implementation agent behaviors in community settings over time have yet to be carried out for the majority of programs. Ongoing (or periodic) assessment of implementer adherence can help identify individuals who are having difficulty accurately and fully delivering components of the intervention. Similarly, measuring implementer competence can provide supervisors with information about implementer delivery quality as well as the targets for remediation. By assessing adherence and competence during the early stages of an intervention, problems with delivery can be identified and addressed in a timely manner. If an evidence-based program cannot be delivered accurately, fully, or with high quality in real-world settings, it may not be feasible to disseminate it widely as it was originally designed.

Training

Individuals such as teachers, coaches, paraprofessionals or other community-based implementers must be trained to a standard to ensure manualized programs are delivered as intended. Measures of adherence and competence have the potential to be very useful in establishing performance standards during the training process and ongoing monitoring (Cross, 2009). For example, assessments by trainers during the initial learning process could be used to rate proportion (adherence) and quality of program delivery (competence). If outcome data are available and levels of adherence and competence associated with positive outcomes are known, trainees may be required to demonstrate a requisite level of adherence and quality of implementation to ‘graduate’ from training. Similarly, site supervisors could be trained to provide ongoing feedback to implementers to maintain effective delivery as part of the monitoring process. In fact, interventionists could be trained to self-rate their adherence to the manual as well as certain competencies (e.g., timing, interactivity) to maintain those individual implementation behaviors. Taken together, the use of adherence and competence measures for program training and monitoring will help prevent implementer drift over time.

Measuring Implementation at the Individual Level

The treatment literature is mixed with respect to the relationship between adherence and outcomes in studies with clinician implementers (Miller & Binder, 2002; Perepletchikova & Kazdin, 2005). Some conclude high adherence reflects therapist rigidity and overreliance on technique, compromising the formation of an effective therapeutic relationship (Castonguay, Goldfried, Wiser, Raue & Hayes, 1996; Henry, Schacht, Strupp, Butler & Binder, 1993). Others have found a positive relationship between adherence and outcomes (Huey, Henggeler, Brondino & Pickrel, 2000) and between adherence in early therapy sessions and early symptom improvement (Barber, Crits-Christoph, & Luborsky, 1996). There is, however, difficulty in interpreting these finding if adherence and competence are not operationalized and assessed separately: Rigid adherence may be a matter of quality of delivery (i.e., competence) for example.

There is emerging evidence that accurate and skillful implementation may have an influence on program outcomes for prevention programs targeting children and adolescents (e.g., Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Greenberg, Domitrovich & Bumbarger, 2001; Rohrbach, Grana, Sussman & Valente, 2006). Nevertheless, the majority of studies fail to report measures of adherence and competence (Dane & Schneider, 1998; Domitrovich & Greenberg, 2000; Durlak, 1997; Waltz et al., 1993). Studies that do report either of these aspects of implementation fidelity seldom provide information on the reliability, validity and psychometric properties of their assessment tools (Brekke & Wolkon, 1988). Without standard definitions and valid and reliable measures, the impact of implementer adherence and competence on clinical outcomes cannot be clearly studied and fully understood. Several important elements of measuring implementer adherence are discussed below.

Implementer Adherence

Implementer adherence is most commonly measured by self-report checklists completed by the implementer, indicating which components of the intervention s/he delivered and/or by the recipient of the intervention who may report on which aspects of the program/intervention s/he received (Henggeler, Melton, Brondino, Schere & Hanley, 1997). Self-report measures of adherence may be categorical (yes/no) or continuous, and may range from single-item to multiple item surveys. The strengths of self-report adherence measures are low cost, ease of administration, and speed of data collection. The accuracy of self-reports, however, is questionable. Studies show, in fact, that implementer self-reports of their own behaviors tend to have low reliability and be positively skewed compared to observational ratings (Miller & Mount, 2001; Moore, Beck¸ Sylvertsen & Domitrovich, 2009). Moreover, the relationship between implementer adherence measured by self-report checklists and clinical outcomes is unclear.

In contrast, observational measures are more reliable and have higher validity than self-reports of implementer behavior (Hansen, Graham, Wolkenstein & Rohrbach, 1991; Harachi, Abbott, Catalano, Haggerty & Fleming, 1999). Observational methods involve an objective rater or team of raters who observe the implementer on site or via videotaped sessions to complete ratings or checklists. The rater(s) records or codes the implementer’s delivery of specific program components prescribed by the program manual. Ratings may be dichotomous (presence/absence) or continuous to reflect the degree of adherence to the prescribed behaviors (Rohrbach, Dent, Skara, Sun & Sussman, 2007; Zvoch, 2009).

The strengths of observational measures of implementer adherence are numerous (Carroll, Nich, Sifry, Nuro, Frankforter et al., 2000; Snyder, Reid, Stoolmiller, Howe, Brown et al., 2006). When recordings are made of program delivery, inter-rater reliability can be easily established. In addition, observational measures have greater accuracy and are more likely to be linked to outcomes than self-report data (Hansen et al., 1991; Hogue et al., 2008; Lillehoj, Griffin & Spoth, 2004). Implementer behaviors can be monitored longitudinally to provide rich information about adherence at different time points during training and implementation. Moreover, when interventions are transported from highly controlled efficacy studies to community and public service settings, observational ratings of community-based implementers’ adherence can provide much needed information about drift and adaptation in the field.

Cost is a significant obstacle to measuring adherence with observational methods, although there are strategies for maximizing cost-effectiveness (Snyder et al., 2006). One methodological criticism of studies using observational measures is the common reliance on a single session which may not be representative (Waltz et al., 1993). Hogue et al. (2008)’s treatment study of adolescent substance abuse is one of few studies with multiple observational measures of implementer adherence. A recent dissemination study by Rohrbach, Gunning, Sun & Sussman (2009) of a drug prevention program in schools is exemplary – these investigators endeavored to conduct two observations to capture a representative measure of implementation fidelity.

Observational measures of implementer program delivery were originally developed for psychotherapy studies of depression treatment to discern the unique and common elements of theoretically different interventions (Shaw, Elkin, Yamaguchi, Olmstead, Vallis, Dobson et al., 1999). Since then other treatment measures of therapist behaviors have emerged. For example, the Yale Adherence Competence Scale (YACS; Carroll, Nich & Rounsaville, 1998; Carroll et al., 2000) is a general system for evaluating therapist adherence and skill across several types of manualized substance abuse treatments and an example of global ratings using observational methods. Because adherence is rated on a likert-type scale, from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extensively), the amount of the intervention content that is delivered cannot be quantified.

When implementer adherence is reported as the number of observed components delivered, the amount of the program content provided is easily quantified. Adherence may also be reported as a categorical variable (highly adherent vs. low adherent). Researchers are encouraged to report the full range of data, however, because categorical designations are arbitrary, provide little specific information for comparison across studies, and may lack generalizability (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Because methods for measuring implementer behaviors are just emerging, descriptions of procedures, measurement development, and descriptive data need to be communicated in the literature (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Dusenbury et al., 2003).

Some studies combine adherence and competence in one measure and do not differentiate between the two constructs. At this stage of prevention implementation research, particularly with non-clinicians, disentangling adherence and competence – and measuring them separately -- is critical to understanding translation of evidence-based programs to communities. We next present an illustration of the development and use of adherence and competence measures in the context of a school-based preventive intervention (Rochester Resilience Project; Wyman, Cross, Brown, Tu & Yu, 2010). We believe that using methods that are generalizable to other manualized programs and offer our measures as templates for others to consider.

Measuring implementer adherence: An illustration

The Rochester Resilience Project is an indicated preventive intervention delivered in schools by highly trained paraprofessionals to children in 1st to 3rd grade with elevated aggressive-disruptive and social-emotional problems identified through a population-based screening. The 24–session manualized intervention is delivered to children in semi-private meetings over two years (Cross & Wyman, 2005). Implementers (Resilience Mentors) teach children a hierarchically-ordered set of skills from emotion self-monitoring to cognitive-behavioral strategies and “coach” children in applying those skills in various contexts. Implementer – child meetings are videotaped (with guardian permission) for coding purposes.

The program manual details the structure and content for each of the 24 sessions. Structurally, each meeting has the same six segments starting with a feelings “check in,” followed by a brief review of the last meeting and subsequent contact with the child, an introduction to the skill, teaching the skill, actively practicing the skill, and finally reviewing and generalizing the skill for use. The content prescribed by the manual differs by session although the structural components do not. For example, in one meeting the implementer must first introduce the concept that feelings have different ‘levels’ by telling an engaging story about a feeling that grows, then teach labels for levels of a variety of feelings (i.e., anger, sadness, happiness, fear), and finally engage the child in role plays and other active learning activities to practice noticing and labeling different feeling intensity. In addition to the six segments of each meeting, sessions are coded for adhering to the designated timeframe (25 +/− 3 minutes).

We developed a session-specific adherence measure for six sessions that focus on skills theoretically core to the intervention and related to outcomes (Session 9, see Appendix A). During the measurement development phase, we consulted the intervention manual, master trainer tapes, and reviewed several hours of various mentors delivering the specific session to a variety of children. We detailed the content of each segment in the session and the scoring rules for coding the specific session. Items are coded as: not at all observed (0), partially observed (1) or fully observed (2) to capture the degree of content delivered for each item. An iterative process of reviewing sessions, coding, and revising the scoring manual ensued followed by a period of coding to establish inter-rater reliability. Once established, coding for sessions was conducted independently with significant overlap between raters and over time (to assess for inter-rater reliability and rater coding drift). We did not expect the adherence rating scales to have high internal consistency because the items are not necessarily related. That is, an implementer’s adherent delivery of one segment (e.g., review of previous session) is not necessarily predictive of adherent delivery of another (e.g., active learning). Internal consistency is expected for competence items, however, because they measure one over-arching construct.

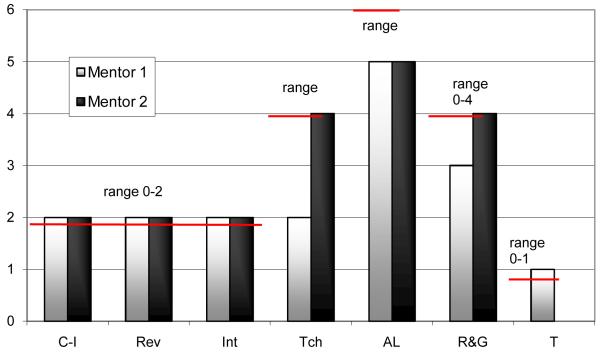

Each observational adherence measure of an implementer–target child meeting results in a total adherence score that can be transformed into “percent of content” delivered, which reflects dose of delivered intervention. Figure 1 shows observational scores on each segment of one session (Session 9, Emotion Regulation) for two implementers delivering to different children. Both implementers are females who were previously employed as classroom aides in elementary schools in the same school district, and trained by the same trainers. Total scores are equivalent for Mentors 1 and 2 who are both highly adherent. The two children received the same amount (80%) or ‘dose’ of the intervention. The quality of implementer delivery, however, cannot be discerned from these scores. We turn now to a discussion of implementer competence.

Figure 1.

Resilience Project Adherence raw scores and range for two implementers*

Key: C-I= Check-in; Rev = Review of previous meeting; Int = Introduction to new skill; Tch = Teach new skill; AL = Active Learning & Practice new skill; R & G = Review of new skill and Generalization to daily context; T= time/duration

*Session 9

Implementer Competence

Treatment studies pioneered research on interventionist competence (e.g., Barberet al., 1996; Creed & Kendall, 2005; Davidson, Scott, Schmidt, Tata, Thornton et al., 2004; Hogue et al., 2008). Behaviors that commonly comprise definitions of therapist competence include: relationship and alliance building behaviors such as validating (Creed & Kendall, 2005), tone of voice (Lochman, Boxmeyer, Powell, Qu, Wells et al., 2009) and collaboration (Creed & Kendall, 2005; Davidson et al., 2004), the ability to correctly teach a specific skill (Lochman et al., 2009), pacing (Davidson et al., 2004), and the ability to tailor the session to the recipient (Creed & Kendall, 2005). Consistent with Waltz et al.’s (1993) conceptualization, some of the techniques that constitute skillful delivery may be specific to the type of intervention rather than general therapeutic competencies even in treatment studies. For example, the Cognitive Therapy Scale (CTS; Trepka, Rees, Shapiro, Hardy & Barkham, 2004) measures therapist behaviors on general interview procedures, interpersonal effectiveness, and specific cognitive-behavioral techniques using a 7-point Likert-type scale. One study found that the more competent therapists, as measured by the CTS, achieved better outcomes for clients who completed therapy (Trepka et al., 2004). Only one session was rated, however, to represent each course of treatment.

In the prevention literature, studies of implementer competence are just emerging but are critical for understanding effectiveness in community-based settings where interventionists are typically non-clinicians. Assessment of implementer competence is also critical during training to ensure that potential implementers are able to deliver the program components with high quality, and similarly, during dissemination to ensure that the program is competently delivered over time. For example, Lochman et al. (2009) included a measure of program delivery quality in a field study of training in the Coping Power Program. The authors used observations of implementer competence and concluded that training intensity was a critical component of successful dissemination. Some outcome studies of community prevention programs include a brief description of how implementer competence is assessed in the training and implementation phases as a means of quality control. For example, Domitrovich, Cortes and Greenberg (2007) describe use of a rating scale by PATHS coordinators who conducted monthly classroom visits in order to assess the quality with which teachers taught and generalized PATHS concepts.

The failure of most studies to assess implementer competence is in large part due to challenges associated with observational measurement (Hogue et al., 2008). Observational ratings of implementer competence require a sophisticated understanding of the intervention (Stiles, Honos-Webb, & Surko, 1998). Unlike adherence ratings that code the presence or absence of specific behaviors, competence measures rate complex behaviors in the context of interpersonal transactions. Reliable measures of implementer competence thus require significant resources for training and elaborate coding procedures. Further contributing to cost, accurate assessment of competence requires coding multiple intervention sessions to capture the interventionist quality reliably (Waltz et al., 1993). Forgatch and colleagues developed an observational fidelity of implementation measure of the Parent Management Training-Oregon program (PMTO; Forgatch, Patterson, DeGarmo & Beldavs, 2009) that is used to code multiple sessions in a course of treatment.

The Fidelity of Implementation Rating System (FIMP; Knutson, Forgatch, & Rains, 2003) measures interventionist ‘competent adherence’ to the PMTO method. This observational measure codes implementer behavior on five domains, using a 9-point scale. High FIMP ratings predict change in observed parenting practices from baseline to 12 months demonstrating a relationship between implementer behaviors and outcomes (Forgatch et al., 2005). The FIMP is integral to the training and certification of PMTO therapists and ensures fidelity to the model as the program is disseminated (Ogden, Forgatch, Askeland, Patterson & Bullock, 2005). PMTO is delivered by professionals with the requisite skills and experiences associated with clinical training. If PMTO implementers were community interventionists or school-based paraprofessionals, separate measures of adherence and competence would likely be useful to differentiate the content from the quality of program implementation for training, outcome and dissemination purposes.

Clearly, as with adherence, the prevention field currently lacks a consistent means of operationalizing and measuring implementer competence and doing so independent of adherence. Below, we describe a competence measure developed for the Rochester Resilience Project.

Measuring implementer competence: An illustration

We developed a single observational measure to rate implementer competence delivering the Rochester Resilience Project (Appendix B). Seven core competencies conceptualized as high quality delivery and hypothesized to be related to positive outcomes are coded. The measured competencies are: 1) emotional responsiveness, 2) boundaries, 3) language, 4) pacing, 5) active learning /practice, 6) individualizing/ tailoring, and, 7) use of in-vivo. Although these competencies may be relevant for a variety of interventions and implementers, paraprofessionals require specific training to develop high quality – competent -- implementation skills. Moreover, consistent with Waltz et al. 1993, we operationalize each of the competencies specifically for the Resilience Project intervention. For example, implementers in the program must use language (Competency 3) that is appropriate for young elementary school children and terminology that is specific to the program. Because the intervention is skill-based, and involves teaching children skills and practicing those skills, the implementer involves children in active learning through role play practice that is engaging behaviorally and affectively. High ratings on this competence domain would be given to a Mentor who first models a skill, then uses a “show me” strategy whereby the Mentor role plays with figures or dolls, and sensitively guides the child to practice the skill. Individualizing sessions and tailoring (Competency 6) are critical to competent Rochester Resilience Project intervention delivery, and the cornerstone of many programs. The implementer is trained to be flexible in delivering the content material to be relevant for each child.

We based the scoring for our observational competence measure on Forgatch et al.’s (2005) FIMP measure. Each competency domain, therefore, is coded on a 9-point scale and can be categorized as ‘good work’ ‘adequate work’ or ‘needs work.’ The Rochester Resilience Project competence measure was developed in an iterative process that began with operationalizing each competency and developing scoring rules, coding multiple intervention meetings, calculating inter-rater reliabilities, and modifying the coding scheme. High internal consistency and inter-rater reliability have been established (Cross, West, Wyman & Schmeelk-Cone, 2009).

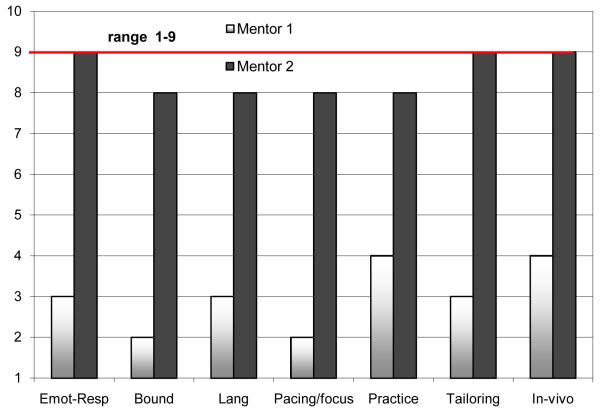

Each session is coded using the general competence measure along with the adherence measure specially developed for each session. Figure 2 illustrates competence scores for Mentor 1 and Mentor 2 for Session 9 (during which a core “resilience” skill is taught and practiced). It shows that Mentor 1’s competence across all domains is much lower than Mentor 2 who shows high quality of implementation for this session.

Figure 2.

Resilience Project Competence raw scores and range for two implementers*

Key: Emot-Resp = Emotional responsiveness; Bound = Boundaries; Lang = Language; Pacing/focus = Pacing of delivery and focus on skill; Practice = Practice and rehearsal engagement; Tailoring = Individualizing material; In-vivo = spontaneous teaching/reinforcing

*Session 9

Recall that the two Mentors scored comparably on the adherence measure for this observed session (Figure 1). They delivered an equal amount or ‘dose’ of the intervention to their child targets. They did so, however, with very different levels of competence. If we were to measure only adherence, or take a checklist approach to fidelity, we would miss a great deal of information about the quality of delivery. It is likely that a child receiving the intervention content in ways that are consistently emotionally responsive, sensitive in terms of language, and tailored to his or her context may benefit more than the child whose mentor is not competent. This is currently an empirical question which we are studying by rating adherence and competence for a variety of children for each mentor, across a number of sessions during the course of the intervention. The goal of the study is to assess the impact of implementer skill—operationalized by ratings of adherence and competence—on child clinical outcomes in a randomized control trial. Because we have multiple sessions available for each implementer-child dyad, we will also be able to quantify the variability of adherence and competence within each course of intervention as well as between dyads.

In addition to studying implementer competence in the context of outcome studies, knowledge about implementer adherence and competence is useful for intervention training programs. For example, PMTO implementers are certified for independent practice based on consistent, satisfactory FIMP ratings. Similarly, one of the goals of the Rochester Resilience Project training program for non-clinicians is to develop an evidence-base for revising training and retaining implementers. We are currently examining observational ratings of implementer adherence and competence early, middle and late in their training to predict implementers that are retained to deliver the intervention with high quality. In addition, the trajectory of successful implementers’ adherence and competence development over time, and the relationship between them, is under study to establish learning curve profiles. The findings from these studies will be used in future training endeavors to improve implementation cost-effectiveness of the program.

Conclusion

Effective implementation is critical for efficacious programs to achieve positive outcomes in real world settings where services are delivered to children. Factors associated with implementation, such as fidelity at the programmatic and implementer level, have been variously conceptualized and measured in the treatment and prevention literatures. Consensus, however, has yet to be achieved. This article focused on the delivery of preventive interventions because they are increasingly delivered by non-clinicians who must be trained to deliver evidence-based interventions with accuracy and quality and, because programmatic effectiveness cannot surpass skill levels of implementers.

In this paper, we discussed individual implementer adherence and competence as separate constructs and have argued that each is important for measuring outcomes, understanding program dissemination (including adaptation in real-world settings) and developing training programs. We illustrated the unique contribution of implementer adherence and competence through measures from a manualized, school-based preventive intervention delivered by paraprofessionals. Measurement development is discussed and examples of measures are provided for others who wish to pursue similar implementation questions. We are in the process of revising these valid and reliable research measures for clinical use by supervisors in the field to provide feedback to implementers about behaviors that have been shown to enhance or impede outcomes.

Critical questions to move forward the field of outcomes research, with implications for training and transport of interventions to communities, are: What level of adherence to manuals and competence in program delivery is “good enough” to ensure positive results? That is, how much of the program content needs to be delivered to the target individual or group, and with what quality of delivery, to achieve positive results? A range of adherence and a minimum level of competence together may be associated with positive outcomes. Secondly, what are the developmental trajectories of these two constructs? There may be a trajectory of adherence that quickly ascends during training and immediately afterward but competence may develop over a more gradual learning curve. In a recent study by Ringwalt, Pankratz, Jackson-Newsom, Gottfredson, Hansen et al. (2010), teachers’ fidelity to a drug prevention curriculum was measured via observational methods over a three-year period. They found that, regardless of their baseline level of proficiency, all teachers regressed to a mean level of implementation fidelity in subsequent iterations of delivering the curriculum. Finally, what is the relationship between adherence and competence? We propose that although there will be some degree of overlap, measuring these constructs separately will provide unique information about program implementation.

Operationalizing, measuring and reporting fidelity at programmatic and individual implementer levels are essential to the growing literature on implementation science. It behooves funders and editors to encourage contributions to this developing knowledge base as studies are reviewed and published. Observational data, while costly, are likely to be most effective during the foundational stages of implementation research in order to understand more fully what is occurring in the transaction among implementer, intervention, and child and to build a solid evidence base to inform service delivery. Once accomplished, the next critical step is to translate findings from rigorous observational research into clinically useful supervisory tools for monitoring and feedback on implementer behaviors in community settings.

Summary of policy & practice implications of research.

Program outcomes cannot surpass the skill level of implementers delivering evidence-based programs in community settings. Implementer fidelity is understudied.

It is critical that interventionists are trained to deliver manualized interventions with adherence to the program content and competence in program delivery. This is particularly true for prevention implementers who are not trained mental health practitioners.

Adherence and competence are related but separate constructs that can be reliably measured. Research tools may be modified and used by supervisors in community-based settings for training and monitoring purposes to provide feedback to interventionists.

Observational measures are the optimal way to reliably measure adherence and competence and to provide important information about program adaptation in the field.

Studies that develop methods to assess adherence and competence should be a priority for research funding agencies. Intervention researchers should be encouraged to report methods that they use to assess implementers’ adherence and competence, and to translate their research measures into clinical and supervisory practices. The cost-effectiveness of offering evidence-based interventions in community settings is likely to be undermined by poorly understood and under appreciated implementation practices.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Cross is currently supported by NIMH (K23MH73615; K23MH073615-03S1). Dr. West receives support through NIMH (R01 R01MH068423, PI: Wyman; K23MH073615-03S1, PI: Cross). We are grateful for the ongoing support of Dr. Peter Wyman and Dr. Eric Caine. We thank Karen Schmeelk-Cone¸ Ph.D. and Holly Wadkins, M.A. for their assistance preparing this article.

Biography

Dr. Wendi Cross is a clinical psychologist specializing in implementation research. Her work focuses on testing models, methods and measures for training individuals charged with carrying forth a variety of evidence-based interventions into community settings. She is Co-Director of the Rochester Resilience Project, a school-based preventive intervention, and is particularly interested in non-clinician implementer training and program delivery.

Dr. Jennifer West is a clinical psychologist, educator and collaborator on training and research in the Rochester Resilience Project. She is interested in the use of observational methodology to assess interventionist skill. She is also Director of the Child and Adolescent Psychology Track of the Doctoral Internship Program in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

Appendix A.

Resilience Project Adherence Measure Session 9 *

| Session 9: Adherence Item |

Structure/section of session |

Item description (see Coding Manual ) | Rating: 0 - 2 |

Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check-in | Use of feelings check-in sheet/feelings poster to reflect child’s feeling | C-I= | |

| 2 | Review | Noticing feeling 2 ways – can be in vivo | Rev = | |

| 3 | Introduction | Dimensions of Feelings – tells a story that illustrates dimensions of a feeling | Int = | |

| 4 | Teaching | 1. Sorts feeling labels from 2 or more dimensions showing increased intensity; using feeling thermometer to elicit child’s experiences with different intensities |

Tch = | |

| 5 | 2. Highlights that high intensity feelings are most difficult to manage and that it is best to stop by using Mental Muscles before becoming out of control/going ‘over the top’ |

|||

| 6 |

Active Learning & practice skill |

1. Uses examples from child’s book/folder (or if legitimately none available, generates one that is relevant to child) to practice concept of feeling intensities |

AL = | |

| 7 | 2. Uses concrete illustration of concept—not just indicating thermometer on wall; child must be engaged in “hands on” activity for ‘2’ |

|||

| 8 | 3. Materials /notes are put in folder to underscore constructs | |||

| 9 | Review & Generalization | 1. Reviews by highlighting feeling words for different intensities/levels and helps to know what causes “over the top” feelings |

R&G = | |

| 10 | 2. indication can try to stop strong feelings (e.g., Mental Muscles, indication of ‘stop’ line on graphic, hot zone area) |

|||

| 11 | 3. Encourages child to notice feelings increase/decrease in intensity in specific daily context | |||

| 12 | Time | 22-28 minutes (goal: 25″) Start: End: | 0 1 | T = |

| Notes: | Total (0-23) = | |||

Rochester Resilience Project, University of Rochester

Contact authors for complete measure and scoring

Appendix B.

Resilience Project Competence Measure *

| Item Number |

Label | Item Description (see Coding Manual) | Good Work | Acceptable Work | Needs Work | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 1 |

Emotional responsiveness |

Ability to respond empathically to the child’s statements and behaviors by reflecting and labeling feelings |

9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | Boundaries | Ability to maintain appropriate psychological and physical boundaries that promote the child’s autonomy and competence |

9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 |

Language/ verbal communication |

Ability to use developmentally appropriate language that clearly conveys both the concepts/skills and the implementer’s empathic connection to the child (e.g., warm, enthusiastic tone, use of specific praise) |

9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | Pacing/ focus | Ability to strategically and sensitively adjust the pace of the session to the needs of the child while remaining focused on relevant aspects of the session content |

9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | Active learning | Ability to effectively use interactive strategies, such as demonstrations and role-plays, to introduce, teach and reinforce concepts and skills |

9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 |

Individualizing / Tailoring |

Ability to use flexibly tailor teaching and concepts/skills so that they are meaningful for the child and his/her context |

9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | In vivo | Ability to use spontaneous material such as the child’s presentation, story, or observations to introduce/teach /reinforce skills or concepts |

9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Rochester Resilience Project, University of Rochester

Contact authors for complete measure and scoring

Footnotes

Portions of the article were presented at the 2nd Annual Conference on the Science of Implementation and Dissemination: Building Research Capacity to Bridge the Gap from Science to Service. NIMH. Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Category: Methodological issues and developments (2) or Evaluation (3)

Contributor Information

Wendi F. Cross, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Rochester, New York, USA.

Jennifer C. West, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Rochester, New York, USA.

References

- Backer TE. The failure of success: Challenges of disseminating effective substance abuse prevention programs. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(3):363–373. [Google Scholar]

- Backer TE. Finding the Balance: Program fidelity and adaptation in substance abuse prevention: A state-of-the-art review. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (DHHS/PHS); Rockville, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, Crits-Cristoph P, Luborsky L. Effects of therapist adherence and competence on patient outcome in brief dynamic therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(3):619–622. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke JS, Wolkon GH. Monitoring program implementation in community mental health settings. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 1988;11(4):425–440. doi: 10.1177/016327878801100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumbarger BK, Perkins DF. After randomized trials: issues related to dissemination of evidence-based interventions. Journal of Children’s Services. 2008;3(2):53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Rounsaville BJ. Use of observer and therapist ratings to monitor delivery of coping skills treatment for cocaine abusers: utility of therapist session checklists. Psychotherapy Research. 1998;8:307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry RL, Nuro KF, Frankforter TL, Ball SA, Fenton L, Rounsaville BJ. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;57(3):225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castonguay LG, Goldfried MF, Wiser S, Raue PJ, Hayes AM. Predicting the effect of cognitive therapy for depression: a study of unique and common factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(3):497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed TA, Kendall PC. Therapist alliance-building behavior within a cognitive-behavioral treatment for anxiety in youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):498–505. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross W. A model of training and transfer of training. Paper presented to the 2nd Annual Conference on the Science of Implementation and Dissemination: Building Research Capacity to Bridge the Gap from Science to Service. NIMH; Bethesda, Maryland. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cross W, West J, Wyman PA, Schmeelk-Cone KH. Disaggregating and measuring implementer adherence and competence. Paper Presented to the 2nd Annual Conference on the Science of Implementation and Dissemination: Building research Capacity to Bridge the Gap from Science to Service; Bethesda, Maryland. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cross W, Wyman PA. Curriculum for the Rochester Child Resilience Project. University of Rochester; Rochester, NY: 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Dane AV, Schneider BH. Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18(1):23–45. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dariotis JK, Bumbarger BK, Duncan LG, Greenberg MT. How do implementation efforts relate to program adherence? Examining the role of organizational, implementer, and program factors. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36(6):744–760. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K, Scott J, Schmidt U, Tata P, Thornton S, Tyrer P. Therapist competence and clinical outcome in the Prevention of Parasuicide by Manual Assisted Behaviour Therapy Trial: the POPMACT study. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34(5):855–863. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson LD, Cook TJ. Avoiding Type III error in program evaluation: results from a field experiment. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1980;3(4):269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Cortes RC, Greenberg MT. Improving young children’s social and emotional competence: a randomized trial of the preschool “PATHS” curriculum. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28(2):67–91. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Greenberg MT. The study of implementation: current finding from effective programs for school-aged children. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation. 2000;11(2):193–221. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA. School-based prevention programs for children and adolescents. Plenum; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JAD, DuPre E. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3-4):327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research. 2003;18(2):237–256. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Freidman RM, Wallace F. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; Tampa, FL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery-Schroeder E. Treatment integrity: implications for training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12(4):388–390. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity: predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon model of parent management training. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS, Beldavs ZG. Testing the Oregon delinquency model with nine-year follow-up of the Oregon Divorce Study. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:637–660. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JC, Coviak CP, Healy TC, Belsa B, Casado BL. Addressing fidelity in evidence-based health promotion programs for older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2008;27(1):4–33. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Domitrovich C, Bumbarger B. The prevention of mental disorders in school-aged children: current state of the field. Prevention and Treatment. 2001;4(1):1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Kusche CA, Cook ET, Quamma JP. Promoting emotional competence in school-aged children: the effects of the PATHS curriculum. Development & Psychopathology. 1995;7(1):117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Graham JW, Wolkenstein BH, Rohrbach LA. Program integrity as a moderator of prevention program effectiveness: results for fifth grade students in the adolescent alcohol prevention trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(6):568–579. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harachi TW, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Haggerty KP, Fleming CB. Opening the black box: using process evaluation measures to assess implementation and theory building. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27(5):711–731. doi: 10.1023/A:1022194005511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Brondino MJ, Schere DG, Hanley JH. Multisystemic therapy with violent and chronic juvenile offenders and their families: the role of treatment fidelity in successful dissemination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:821–833. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry WP, Schacht TE, Strupp HH, Butler SF, Binder JL. Effects of training in time-limited dynamic psychotherapy: changes in therapist behavior. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(3):434–440. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill LG, Maucione K, Hood BK. A focused approach to assessing program fidelity. Prevention Science. 2007;8(1):25–34. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Henderson CE, Dauber S, Barajas PC, Fried A, Liddle HA. Treatment adherence, competence, and outcome in individual and family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(4):544–555. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Henggeler SW, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Mechanisms of change in multisystemic therapy: reducing delinquent behavior through therapist adherence and improved family and peer functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):451–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings J, Bywater T, Eames C, Martin P. Implementing child mental health interventions in service settings: lessons from three pragmatic randomised controlled trails in Wales. Journal of Children’s Services. 2008;3(2):17–27. [Google Scholar]

- James IA, Blackburn IM, Milne DL, Reichfelt FK. Moderators of trainee therapists’ competence in cognitive therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;40(2):131–141. doi: 10.1348/014466501163580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson NM, Forgatch MS, Rains LA. Fidelity of Implementation Rating System (FIMP): the training manual for PMTO. Oregon Social Learning Center; Eugene: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj CJG, Griffin KW, Spoth R. Program provider and observer ratings of school-based preventive intervention implementation: agreement and relation to youth outcomes. Health Education and Behavior. 2004;31(2):242–257. doi: 10.1177/1090198103260514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman J, Boxmeyer C, Powell N, Qu L, Wells K, Windle M. Dissemination of the Coping Power Program: importance of intensity of counselor training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):397–409. doi: 10.1037/a0014514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugo J, Drake RE, Whitley R, Bond GR, Campbell K, Rapp CA, Goldman HH, Lutz WJ, Finnerty MT. Fidelity outcomes in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(10):1279–1284. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.10.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic SF, Irwin K. Blueprints for violence prevention: from research to real-world settings--factors influencing the successful replication of model programs. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2003;1(14):307–329. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SJ, Binder JL. The effects of manual-based training on treatment fidelity and outcome: a review of the literature on adult individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory/Research/Practice/Training. 2002;39(2):184–198. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Mount KA. A small study of training in motivational interviewing: Does one workshop change clinician and client behavior? Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Moore JE, Beck TC, Sylvertsen A, Domitrovich C. Making sense of implementation: multiple dimensions, multiple sources, multiple methods. Paper presented to the 17th Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; Washington, DC, USA. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden T, Forgatch MS, Askeland E, Patterson GR, Bullock BM. Implementation of parent management training at the national level: the case of Norway. Journal of Social Work Practice. 2005;19(3):317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity and therapeutic change: issues and research recommendations. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12(4):365–383. [Google Scholar]

- Poduska J, Kellam S, Brown CH, Ford C, Windham A, Keegan N, Wang W. Study protocol for a group randomized controlled trial of a classroom-based intervention aimed at preventing early risk factors for drug abuse: integrating effectiveness and implementation research. Implementation Science. 2009;4(56):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwalt CL, Ennett S, Johnson R, Rohrbach LA, Simons-Rudloph A, Vincus A, Thorne J. Factors associated with fidelity to substance abuse prevention curriculum guides in the nation’s middle schools. Health Education and Behavior. 2003;30(3):375–391. doi: 10.1177/1090198103030003010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwalt CL, Pankratz MM, Jackson-Newsom J, Gottfredson NC, Hansen WB, Giles SM, Dusenbury L. Three-year trajectory of teachers’ fidelity to a drug prevention curriculum. Prevention Science. 2010;11:67–76. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0150-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach LA, Dent CW, Skara S, Sun P, Sussman S. Fidelity of implementation in Project Towards No Drug Abuse (TND): a comparison of classroom teachers and program specialists. Prevention Science. 2007;8(2):125–132. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0056-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach LA, Grana R, Sussman S, Valente T. Type II translation: transporting preventive interventions from research to real-world settings. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2006;29(3):302–333. doi: 10.1177/0163278706290408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach LA, Gunning M, Sun P, Sussman S. The Project Towards No Drug Abuse (TND) dissemination trial: implementation fidelity and immediate outcomes. Prevention Science. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0151-z. published online September 15, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BF, Elkin I, Yamaguchi J, Olmstead M, Vallis TM, Dobson KS, et al. Therapist competence ratings in relation to clinical outcome in cognitive therapy of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(6):837–846. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Reid J, Stoolmiller M, Howe G, Brown CH, Dagne G, Cross W. Measurement systems for randomized intervention trials: the role of behavioral observation in studying treatment mediators. Prevention Science. 2006;7(1):43–56. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Clair S, Greenberg M, Redmond C, Shin C. Toward dissemination of evidence-based family interventions: maintenance of community-based partnership recruitment results and associated factors. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(2):137–146. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles WB, Honos-Webb L, Surko M. Responsiveness in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5(4):438–458. [Google Scholar]

- Trepka C, Rees A, Shapiro DA, Hardy GE, Barkham M. Therapist competence and outcome of cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28(2):143–157s. [Google Scholar]

- Waltz J, Addis ME, Koerner K, Jacobson NS. Testing the integrity of a psychotherapy protocol: assessment of adherence and competence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(4):620–630. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren HK, Domitrovich CE, Greenberg MT. Implementation quality in school-based research: roles for the prevention researcher. In: Dinella LM, editor. Conducting science-based psychology research in schools. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2009. pp. 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman PA, Cross W, Brown CH, Tu X, Yu Q. Intervention to strengthen emoitonal self-regulation in children with emerging mental health problems: Proximal impact on school behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9398-x. published Online First, Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvoch K. Treatment fidelity in multisite evaluation: A multilevel longitudinal examination of provider adherence status and change. American Journal of Evaluation. 2009;30(1):44–61. [Google Scholar]