Abstract

Recent technical advances have rapidly advanced the discovery of novel peptides, as well as the transcripts that encode them, in the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum. Here we report that many of these novel peptides produce profound and varied effects on locomotory behavior and levels of cyclic nucleotides in A. suum. We investigated the effects of 31 endogenous neuropeptides encoded by transcripts afp-1, afp-2, afp-4, afp-6, afp-7, and afp-9 - 14, (afp: Ascaris FMRFamide –like Precursor protein) on cyclic nucleotide levels, body length and locomotory behavior. Worms were induced to generate anteriorly propagating waveforms, peptides were injected into the pseudocoelomic cavity, and changes in the specific activity (nmol/mg protein) of second messengers cAMP (3′5′ cyclic adenosine monophosphate) and cGMP (3′5′ cyclic guanosine monophosphate) were determined. Many of these neuropeptides changed the levels of cAMP (both increases and decreases were found), whereas few neuropeptides changed the level of cGMP. A subset of the peptides that lowered cAMP was investigated for effects on the locomotory waveform and on body length. Injection of AF19, or AF34 (afp-13), AF9 (afp-14), AF26 or AF41 (afp-11) caused immediate paralysis and cessation of propagating body waveforms. These neuropeptides also significantly increased body length. In contrast, injection of AF15 (afp-9) reduced the body length, and decreased the amplitude of waves in the body waveform. AF30 (afp-10) produced worms with tight ventral coils. Although injection of neuropeptides encoded by afp-1 (AF3, AF4, AF10 or AF13) produced an increased number of exaggerated body waves, there were no effects on either cAMP or cGMP. By injecting peptides into behaving A. suum, we have provided an initial screen of the effects of novel peptides on several behavioral and biochemical parameters.

Keywords: Neuropeptides, cAMP, cGMP, Ascaris suum, locomotory behavior, parasite

1. Introduction

Neuropeptides are well established as signaling molecules and are widespread and numerous across animal phyla. They function as neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, affecting many different physiological properties of their target cells [1]. Neuropeptides have been particularly well studied in nematodes, where the discovery of new peptides has been approached by two general methods, chemical analysis of the peptides themselves [2–11], and database mining of genomic or EST libraries [12–15]. Localization studies in nematodes show that the majority of these neuropeptides are expressed in neurons [11, 16–20]. Neurons in nematodes are few in number and are simple geometrically. The adult hermaphrodite Caenorhabditis elegans has 302 neurons [21], and adult female Ascaris suum has 298 neurons [22], and the morphology of these neurons is, in most cases, unusually simple [21, 23] with at most two branch points. Neuronal morphology is conserved between the two species, with the neurons differing in little else but size. This is remarkable considering that nematodes are estimated to have diverged evolutionarily about 550 million years ago [30].

Both Caenorhabditis elegans and Ascaris suum contain a large number of peptides; each species has been estimated to encode about 250 different peptides [5, 11]. Many of the peptides are known to have potent activity on subsets of neurons and/or on muscle cells, as well as on locomotory behavior [2, 4–9, 24–29]. The sequences of these neuropeptides are also highly conserved among different species of nematodes, being either identical or very similar, implying strong positive selection pressure on the sequences. The fact that there are so many peptides in nematodes suggests that they may have a correspondingly large number of important functional roles.

In this laboratory, we have explored the role of neuropeptides at the cellular, physiological and behavioral levels. We investigate both the transmitting cell and the receiving cell that constitute the intercellular signaling dyad mediated by the peptide. To identify the cells that produce and presumably secret these peptides, we use three different approaches: immunocytochemistry with highly specific antibodies against individual peptides [31], in situ hybridization with riboprobes derived from cloned genes encoding the peptides [32], or direct analysis of peptide content by mass spectrometry of single dissected neurons [6]. In almost all cases the three techniques give the same answer. The other half of the cellular signaling dyad, namely the cells bearing the receptors for each peptide, has been explored by observing peptide effects on the electrophysiological properties of single neurons [9, 24], on muscle cells [7, 8, 25–27, 29, 33–35], and on levels of cAMP [28, 36].

We have long been interested in the effects of neuropeptides on the locomotory behavior of A. suum [24, 28]. The importance of locomotion in nematode behavior has been summarized by Croll [37, 38]. In parasitic nematodes locomotion is crucial for the migration of the various life form stages during the parasitic life cycle, and, for many adult intestinal nematodes, locomotion is used to maintain position within the intestine. Nematodes make a variety of body movements, including twisting into a corkscrew, and coiling; they also generate waveforms in the body, and the propagation of these waveforms is responsible for locomotion. The number of wave crests within each waveform and the direction of propagation may vary. In A. suum, alternating dorsal and ventral muscle contraction and relaxation cycles generate the body bends that constitute the propagating waveform. In the host intestine, where the worm braces its body against the intestinal wall, the direction of waveform propagation is the same as the direction of locomotion, so, unlike in C. elegans, forwards propagating waves produce forward locomotion [37]. These movements can be observed in a glass tube with a diameter similar to that of the lumen of the small intestine of the pig.

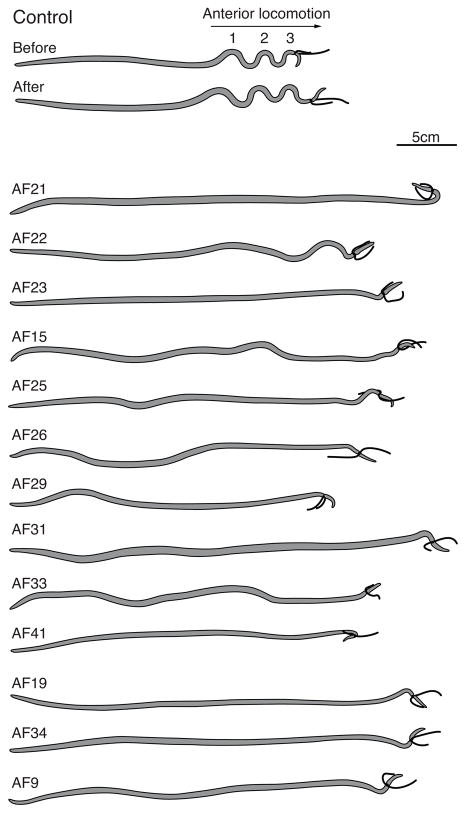

To establish a baseline of locomotory behavior, all A. suum used in this study were ligatured at the head with surgical thread, which induces stereotypical anteriorly-propagating body waves [28, 39]. These waves are initiated in the region of the gonopore in females. For the typical female adult, after placement of the ligature there are generally three crests in the anteriorly propagating waveform (Figure 1). A. suum is large enough that neuropeptides can easily be injected into the pseudocoelomic cavity posterior to the ligature. This minimally invasive technique keeps the neuromuscular system intact for monitoring the effects of peptides on behavior and body length, as well as on downstream signal transduction events.

Figure 1.

Postures of worms after injection of neuropeptides. Heads are to the right. All injected peptides disrupted locomotory behavior, either completely abolishing all movements and producing a straight worm, or producing a severe reduction in the generation and propagation of locomotory waveforms. Control: Digital image of A. suum generating a typical locomotory waveform. Ligaturing the head induces anterior propagation of waveforms. Generally there are three waveforms present in the anterior region and they propagate in the anterior direction. After injection of control saline there is no change in behavior.

In previous experiments we analyzed the effects of six endogenous A. suum peptides and five peptides from C. elegans, and showed that most peptides produced significant effects on behavior [28]. Some peptides also produced changes in cAMP levels, and both increases and decreases were seen. In the present paper we extend our previous analyses by assaying the effects of 31 endogenous A. suum peptides (Table 1) on both cAMP and cGMP, as well as on locomotory behavior, body length, and body tonus. We report results on peptides encoded by the transcripts afp-1 [40], afp-2 [51], and afp-4 [32], as well as on the more recently discovered peptides encoded by afp-6 [9], afp-7 [41], afp-9, afp-10 [42], afp-11 [42, 51], afp-12 and afp-13 [6], and afp-14 [C. Konop, pers.comm.].

Table 1.

A. suum neuropeptides and the transcripts that encode them.

| Neuropeptide | Transcript | Sequence | C. elegans homolog |

|---|---|---|---|

| AF1 | afp-7 | KNEFIRFa | flp-8 |

| AF2 | afp-4 | KHEYLRFa | flp-14 |

| AF3 | afp-1 | AVPGVLRFa | flp-18 |

| AF4 | afp-1 | GDVPGVLRFa | flp-18 |

| AF10 | afp-1 | GFGDEMSMPGVLRFa | flp-18 |

| AF13 | afp-1 | SDMPGVLRFa | flp-18 |

| AF5 | afp-2 | SGKPTFIRFa | flp-4 |

| AF21 | afp-6 | AMRNALVRFa | flp-11, flp-32 |

| AF22 | afp-6 | NGAPQPFVRFa | flp-11 |

| AF23 | afp-6 | SGMRNALVRFa | flp-11 |

| AF15 | afp-9 | AQTFVRFa | flp-16 |

| AF30 | afp-10 | APNKILMRFa | flp-28 |

| AF11 | afp-11 | SDIGISEPNFLRFa | flp-1 |

| AF25 | afp-11 | NNFLRFa | flp-1 |

| AF26 | afp-11 | KPNFLRFa | flp-1 |

| AF27 | afp-11 | PADPNFLRFa | flp-1 |

| AF28 | afp-11 | SAEPNFLRFa | flp-1 |

| AF29 | afp-11 | NAEPNFLRFa | flp-1 |

| AF31 | afp-11 | TPSNNFLRFa | flp-1 |

| AF32 | afp-11 | GSDPNFLRFa | flp-1 |

| AF33 | afp-11 | SNQAQNFLRFa | flp-1 |

| AF41 | afp-11 | KPNFIRFa | flp-1 |

| TF | afp-11 | TAPPLTFa | |

| NY | afp-11 | NDQFDREY | |

| AF36 | afp-12 | VPSAADMMIRFa | flp-24 |

| AF19 | afp-13 | AEGLSSPLIRFa | flp-13 |

| AF34 | afp-13 | DSKLMDPLIRFa | flp-13 |

| AF35 | afp-13 | DPQQRIVTDETVLRFa | |

| TT | afp-13 | TPPEEDLLGRFT | |

| TL | afp-13 | TNIMGENRLNRNL | |

| AF9 | afp-14 | GLGPRPLRFa | flp-21 |

Accession numbers. afp-1: U15279; afp-4: AY386834; afp-6: AY705391; afp-9: BM518433; afp-12: HM125966; afp-13: HM125967; flp-1: F23B2.5; flp-4: C18D1.3; flp-8: F31F6.4; flp-11: K02G10.4; flp-13: F33D4.3; flp-14: Y37D8A.15; flp-16: F15D4.8; flp-18: Y48D7A.2; flp-21: C26F1.10; flp-24: C24A1.1; flp-28: W07E11.4; flp-32: R03A10.2.

We report for the first time the effects of these peptides on cGMP, a well-known second messenger in other systems: we observed both increases and decreases. We also extend the list of peptides that increase or decrease cAMP levels. There is a loose correlation between the changes in cyclic nucleotides and body length: in general, increases in cAMP are associated with contraction of the body, although there is a marked exception for AF2 which produces the largest change in cAMP, yet no change in body length [28]; similarly decreases in cAMP are generally associated with body relaxation. It is striking that in the case of multiple peptides derived from a single transcript, the activities of the individual peptides are not always identical. Divergent activities of the different products of a single transcript have been observed previously for the afp-6 transcript in A. suum [9], and the flp-18 peptides of C. elegans [43].

One reason for our interest in neuropeptides in nematodes is to address the growing resistance to currently available anthelmintics. Since nematode locomotion is a prime target for anthelminthic action, we aim to identify potential new targets for future anthelminthic development by characterizing the peptide-mediated signaling pathways that are involved in locomotory behavior.

2. Material and methods

A. suum were collected at a local slaughterhouse from the small intestines of freshly killed pigs, and stored at 37 °C in PBS (140 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4). In these experiments, large female worms 25–40 cm were used within 30 h of collection.

2.1 Head ligature procedure

In all second messenger assays and all behavioral and body length change determinations, A. suum were induced to generate stereotypical anteriorly propagating locomotory waveforms by ligaturing the worm with surgical thread ca. 5 mm posterior to the pharynx.

2.2 cAMP and cGMP second messenger assays

For the second messenger assays, the A. suum were injected (27.5 gauge needle) just behind the ligature with 100 μl 10 μM test neuropeptide in Ascaris saline (4 mM NaCl, 125 mM sodium acetate, 24.5 mM KCl, 5.9 mM CaCl2, 4.9 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM MOPS buffer, pH 6.8), or with control saline, and then placed in a beaker containing PBS at 37 °C. Previous experiments with injection of 100 μl of dye solution showed that there was a ca. 10-fold dilution in the region of the injection, so that target cells were exposed to ca. 1 μM peptide [39]. After observing general behavioral effects, namely body tonus immediately after injection (stiff or relaxed), the shape of the body (straight or curved) and whether or not propagating waveforms were affected, the worms were frozen in liquid nitrogen 5 – 7 minutes after injection. A ca. 2 cm piece of worm from the injected region was excised and stored at −80 °C.

Tissue preparation for the determinations of cAMP and cGMP were made as previously described [28]. Briefly, the frozen tissue was homogenized in 750 μl ice-cold 6% TCA, and then centrifuged, and the supernatant extracted with ether to remove TCA. cAMP and cGMP were assayed by ELISA (BioVision cAMP or cGMP assay kit) or RIA (New England Nuclear). Both samples and standards were acetylated to improve the sensitivity of the assays [44]. The 1% Triton X-100 soluble protein in each TCA pellet was determined (Bradford reagent [45]) in order to calculate the specific activity of each cyclic nucleotide (nmol/mg protein). A Student’s t-test was used to test for significance of the neuropeptide-induced changes compared to controls.

Most determinations of cyclic nucleotides were made by ELISA. In our previously reported experiments [28], cAMP was assayed by RIA, so to ensure that the results with ELISA were comparable some determinations were made by both RIA and ELISA. Additional validation of the ELISA assays was accomplished by spiking A. suum samples with a series of cAMP or cGMP standards. In each case, the arithmetic sum of the standard plus the amount contributed by the worm was found, showing that there was no interference from A. suum material in the assays.

2.3 Photo-documentation of locomotory posture and body length determinations

For the body length determinations, worms were ligatured as described above, and placed in a glass tube (18 mm internal diameter × 41 cm in length fitted with stoppers) containing PBS maintained at 37 °C. The worm was photographed with a Nikon D50 digital camera before and after injection against a background transparent centimeter grid. Images for body length determinations were made 3–6 minutes before and after injection. The images were encoded with a random file name and stored in batches of 50 to 100 files, then body lengths were measured in ImageJ (NIH) using images magnified up to 4X on the screen in order to reduce ambiguity about the positions of the lips and the tail. At least ten determinations of each worm’s body length were averaged to give the body length for each worm. Worms that showed coiling were not measured. After the analysis was complete, the images were decoded. The average percent change in body length and the standard error for each treatment was computed and compared to control worms. A Student’s t-test was used to test for significance.

2.4 Source of neuropeptides

Neuropeptides were synthesized by the UW-Madison Biotechnology Center, and were over 99% pure as determined by HPLC. The molecular mass of each peptide was determined by MALDI-TOF MS as a further control of the quality of the synthesis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Head – Restricted Behavior

The utility of a head ligature for inducing the stereotypical Head-Restricted Behavior [39] was first discovered when we were attempting to refine the markedly varied behavior observed when A. suum is placed in a large beaker of PBS. In this environment, the locomotory behavior is largely unpredictable, consisting of alternating bouts, of variable duration, of forwards- and backwards-moving waveforms, superimposed upon apparently random body bends that can sometimes form knots. By prolonged observation, it is possible to observe the effects of injected peptides on locomotory behavior [9, 24, 28], but we (J.E. Donmoyer and A.O.W. Stretton, unpublished) sought a way to induce standardized behavior by applying to the head (where the sensory receptors are concentrated) compounds that might act as attractants (like the presence of the opposite sex) or repellents (like garlic), while leaving the rest of the body free for observation of locomotory behavior. We devised an apparatus consisting of a glass trough with two compartments separated by a sheet of dental rubber dam. The head was inserted through a hole in the dam, and we varied the diameter of the hole to minimize leakage. When the head was squeezed tightly enough to prevent leakage, the worm generated forwards-moving waves without the necessity of chemical stimulation. We found that a head ligature produced the same effect, generating the standardized behavior we were seeking. A similar effect is produced by decapitation, but the useful lifetime of the preparation is reduced as the turgor pressure goes down due to leakage of the pseudocoelomic fluid. The basis for the behavioral bias produced by the ligature is not clear. The ligature is placed posterior to the pharynx, so the nerve ring and its associated sensory neurons are well separated from the rest of the body. The appropriate tightness of the ligature was determined by injections of Fast Green solution (10 mg/ml) into the posterior or anterior side of the ligature: when the ligature was tight enough to produce the standardized behavior, there was no diffusion between the injected and non-injected side. We presume that the ligature prevents conduction of nerve signals past the ligature, but have no proof for this assumption. Many of the peptides we investigate in this paper are encoded by the afp-11 transcript that is expressed in the paired AVK neurons in the ventral ganglion [51]. The cell bodies of these neurons are separated from the body by the ligature, but the ventral cord processes of AVK extend into the region of the worm posterior to the ligature [51], which is where injected peptides act, so we surmise that the behavioral effects of injected peptides encoded by afp-11 are relevant to the natural effects of peptides released from the AVK processes.

3.2 Effects of neuropeptides on cAMP and cGMP responses, body length and locomotory behavior

Almost all of the neuropeptides tested here (Table 1) are AF peptides, with C-terminal RFamide. Peptides NY, TT and TL are intervening sequences between AF peptides encoded by afp-11 or afp-13, and are known to be expressed since they were detected by single-cell MS [6]. Peptide TF was predicted, but its expression has not yet been confirmed.

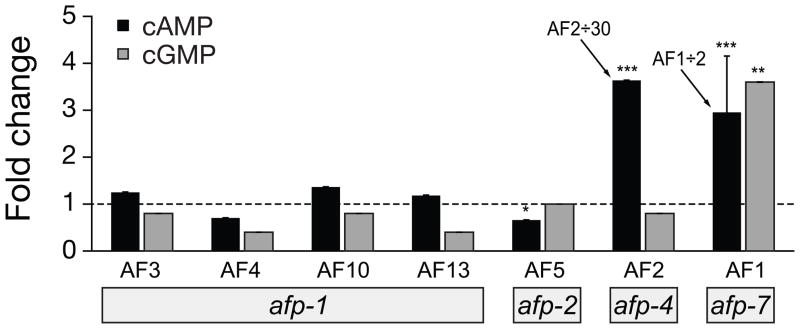

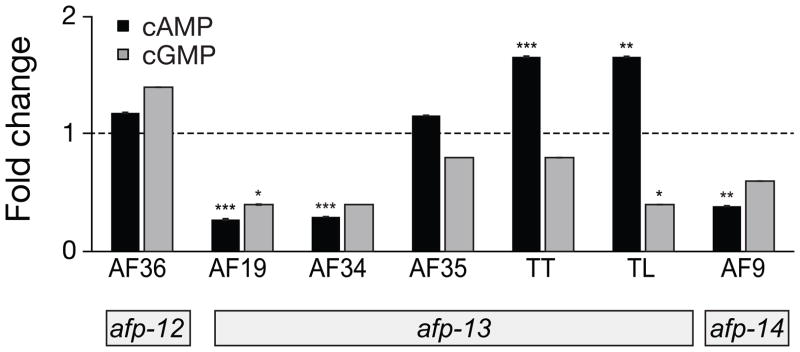

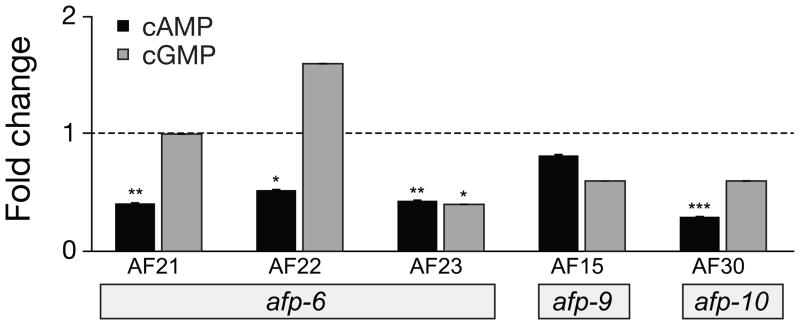

The effects of neuropeptides on levels of cAMP and cGMP are shown in Figures 2 – 5 as fold changes from control levels after injection of saline. Numerical values of specific activity are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Control injections produced no significant changes in cAMP or cGMP, and no change in posture; the worms still have at least three propagating wave crests in the anterior region (Figure 1). Control injected worms did not show a significant change in body length (Table 2). Basal levels of cAMP and cGMP were in good agreement with the values reported in A. suum by Thompson et al. [36]

Figure 2.

cAMP and cGMP fold changes relative to control after injection of peptides encoded by afp-1, afp-2, afp-4, and afp-7. Peptides were injected in 100 μl volumes at a concentration of 10 μM unless indicated otherwise. Black bars, cAMP; gray bars, cGMP (this convention is used in subsequent figures). Since AF2 and AF1 caused elevation of cAMP far beyond the scale of the other treatments shown, their calculated cAMP fold changes were divided as indicated. Standard error bars are shown. Significance, (Student’s t-test): * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001

Figure 5.

cAMP and cGMP responses to injections of the neuropeptides encoded by afp-12, afp-13, and afp-14. AF19 and AF34 dramatically decreased cAMP levels whereas peptide TT and TL (not RFamide-like) elevated cAMP. Standard error bars are shown. Significance (t-test): * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Effects on body length produced from 10 μM injection of neuropeptides.

| Treatment | Mean % Change a | Posture |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.4 ± 0.2 (20) | 2–3 propagating waveforms |

| AF1 | −5.3 ± 0.6 (13)*** | shallow crest, no propagation |

| AF30 | n.d. (6) | ventral coil |

| AF21 | 3.8 ± 0.7 (5)*** | linear, no propagation |

| AF22 | 4.7 ± 0.7 (8)*** | broad static waveform |

| AF23 | 10.6 ± 1.5 (7)*** | linear, no propagation |

| AF15 | −2.3 ± 2.2 (6) * | shallow crest, no propagation |

| AF25 | 4.5 ± 1.4 (5) *** | linear, no propagation |

| AF26 b | 6.2 ± 0.6 (5) *** | linear, no propagation |

| AF29 | 7.1 ± 2 (5) *** | linear, no propagation |

| AF31 | 7.4 ± 2 (6) *** | linear, no propagation |

| AF33 | 0.5 ± 1 (5) *** | broad static waveform |

| AF41 c | 4.5 ± 0.7 (5) *** | linear, no propagation |

| AF19 | 8.7 ± 2.0 (6) *** | linear, no propagation |

| AF34 | 7.7 ± 2.2 (8) *** | linear, no propagation |

| AF9 | 7.8 ± 1.5 (8) *** | linear, no propagation |

t-test was applied to determine significance.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

100 μM injected.

5 μM injected.

3.2.1 Effects of peptides encoded by afp-1 (AF3, 4, 10, 13)

In A. suum treated with neuropeptides AF3 (AVPGVLRFa), AF4 (GDVPGVLRFa), AF10 (GFGDEMSMPGVLRFa), and AF13 (SDMPGVLRFa), all encoded by afp-1 [40], there are no significant changes in either cAMP or cGMP levels (Figure 2). However, these peptides do have strong effects on locomotory behavior. In head-ligatured worms generating anteriorly propagating locomotory waves, injection of any of the neuropeptides encoded by the afp-1 transcript increased the number of crests in the locomotory waveform. This was also observed after peptide injection into worms with or without ligatures and free in a beaker, rather than in a tube [24], and we have confirmed these results. A significant decrease in body length (contraction) was produced after injection with AF10 [28]. Previous studies have shown that these peptides have very little effect on the electrophysiological properties of motor neurons [24]. The afp-1 neuropeptides were not investigated further in this study.

3.2.2 Effects of peptides encoded by afp-2 (AF5), afp-4 (AF2), and afp-7 (AF1)

As shown in Figure 2, AF5 (SGKPTFIRFa) produced a significant decrease in cAMP (0.029 nmol/mg +/− 0.004, p < 0.05). In worms without ligatures, Davis and Stretton [24] described the behavioral effects of AF5 as being similar to those of AF1, with marked decreases in locomotory movements and reduced amplitude of body waves. The increase in body tonus immediately after injection of AF5 was also similar to those observed for AF1 [24]. AF5 and AF1 are similar in that they share a FIRFamide C-terminal sequence, and each has a lysine residue seven amino acids from the C terminus.

Figure 2 also shows the changes in cAMP and cGMP produced by AF2 (KHEYLRFa, afp-4) or AF1 (KNEFIRFa, afp-7). We previously demonstrated that both AF1 and AF2 dramatically elevated cAMP [28], but the effects on cGMP levels were not determined. In the present experiments, AF1 increased cAMP 6-fold (comparable to previous results obtained with a different assay [28]) and increased average cGMP 6-fold, although the range was large (17 – 0.7 times control), and increases were seen in only 6/16 cases; the reasons for this high variability are unknown. In contrast, AF2 dramatically increased cAMP, by 175-fold, but had no effect on cGMP levels. Thompson et al. [36] have confirmed our results on the effects of AF1 and AF2 on cAMP levels, but did not observe any effect of AF1 on cGMP levels.

In another experiment, we followed the time course of the responses of cGMP to a higher dose (100 μM) of AF1. We confirmed that cAMP levels continue to rise for up to 45 minutes after injection, as in previous experiments [28], but there was no significant change in cGMP during the same time period. This contrasts with the effects on cGMP of the lower dose of AF1, suggesting that the peptide may have multiple sites and/or mechanisms of action on cGMP.

In a few experiments we injected control saline or 10 μM AF1 into the head region anterior to the ligature, and assayed for cAMP and cGMP in heads. In control worms, the specific activity for cGMP was below the detection limit of our assay. In AF1-treated worms, cAMP was elevated relative to control but control specific activity of cAMP from the head was much lower than from the more posterior region of the worm (data not shown). Because of the low levels of cyclic nucleotides that could be detected from single heads, these experiments were not pursued further.

We previously found that AF1 injections produce worms that are paralyzed, have stiff tonus and shallow waveforms [28]. AF1 also increases muscle tension [4] and depolarizes the excitatory motor neuron DE2 [24]. The response to AF2 is different. The posture produced by injection of AF2 is similar to that produced by AF1 (contracted shallow crests, not shown) [28], but AF2-injected worms make intense thrashing jerky flexions, perhaps associated with backward propagating waveforms. AF2 also produces a biphasic change in muscle tension, an initial relaxation followed by a sustained contraction [2].

Both AF1 and AF2 can elevate cAMP and they have been shown to have distinct receptors in A. suum [29]. Brief application of AF2 produces a lasting potentiation of ACh responses in muscle strips. It is thought that multiple interacting second messenger systems elements are involved in the AF2 regulation of muscle, but our results suggest that cGMP is not one of them.

3.2.3 Effects of peptides encoded by afp-6 (AF21, 22, 23)

Figure 3 shows changes observed in levels of cAMP and cGMP following treatment with AF21 (AMRNALVRFa), AF22 (NGAPQPFVRFa), and AF23 (SGMRNALVRFa), which are encoded by the afp-6 transcript [9]. All three neuropeptides produced significant decreases in cAMP and one of them, AF23, significantly decreased cGMP. Each of the three afp-6 peptides produced a significant lengthening of the body (AF23>AF22=AF21) and abolition, or near abolition, of the body waveform (Figure 1, Table 2). A. suum treated with AF22 showed loss of waveform propagation and a reduction in the amplitude of most waveforms; the waveform in the region near the gonopore where the waveforms normally originate remained static. AF21 and AF23 produced similar locomotory posteriors that were noticeably more flattened than the posture from AF22 injections.

Figure 3.

cAMP and cGMP responses to injection of 10 μM neuropeptides encoded by the transcripts afp-6, afp-9, and afp-10. Neuropeptides AF21, AF22, and AF23 (afp-6) and AF30 (afp-10) significantly lowered cAMP. A significant decrease in cGMP was observed following AF23 injections. Standard error bars are shown. Significance (t-test): * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

It is interesting to compare these responses to the electrophysiological effects of these peptides that were described previously [9]. The responses of muscle to 10 μM macrophoretic application of peptide showed that AF21, 22, and 23 all produced muscle hyperpolarization and relaxation, with relative potency AF22>AF21=AF23. However, the effects of AF22 on motor neurons AF22 differed dramatically from effects of AF21 and AF23. Whereas AF22 hyperpolarized excitatory motorneurons DE1 and DE2 and inhibitory motorneuron DI, with little effect on input resistance, AF21 and AF23 produced strong depolarization in DE1, DE2, and DI, accompanied by a large reduction in input resistance [9].

While in the electrophysiological experiments AF21 and AF23 had similar effects, in the second messenger assay AF21 and AF23 have different actions. The effects of these three peptides on motor neurons clearly involve signal transduction pathways in addition to cyclic nucleotides, and merit further study.

Among nematodes, all three peptides are highly conserved, which implies a strong positive selective pressure on each of these sequences. AF22 is structurally quite distinct from AF21 and AF23. Although AF21 and AF23 are sequence related, they have separately conserved sequences; the AF21-related consensus is AMRNALVRFa, while the most common sequence for the AF23-related peptides is (A/S)GMRNALVRFa, sometimes with two additional N-terminal amino acid extensions [9]. In several other nematodes there are two separate gene families, one of which encodes all three AF21, 22 and 23 sequelogs, while the other encodes only one of these peptides, AF21 or its close relative AMRNSLVRFa [5]. At least in C. elegans, it is known that both genes, flp-11 and flp-32, are expressed [5].

3.2.4 Effects of peptides encoded by afp-9 (AF15) and afp-10 (AF30)

Afp-9 encodes three copies of AF15 (AQTFVRFa). Although AF15 has no effect on either cAMP or cGMP (Figure 3, Supplemenatry Table 1), it is a potent inhibitor of locomotion. After injection of AF15, the body of the worm is stiff and contracted (Table 2); waveform propagation is inhibited, although there are some regions of the body that adopt low amplitude body bends (Figure 1). These effects are not correlated with changes in cyclic nucleotide levels.

Peptide AF30 (APNKILMRFa), which is encoded by afp-10 [42], produces a decrease in cAMP, but has no significant effect on cGMP (Figure 3). AF30 produced ventral coils in 4 out of 6 A. suum. We have no information on effects on body length since ventral coiling interferes with the measurements. It is interesting that peptide AF8 (encoded by afp-3 [32]), which was tested previously [28], also produces ventral coils, but since AF8, unlike AF30, does not change cAMP levels, we conclude that ventral coiling does not necessarily involve changes in cAMP. AF8 (KSAYMRFa) has been shown to relax dorsal muscle and contract ventral muscle [46], consistent with the generation of ventral coils. It may be relevant that both AF8 and AF30 share a C-terminal –MRFa sequence.

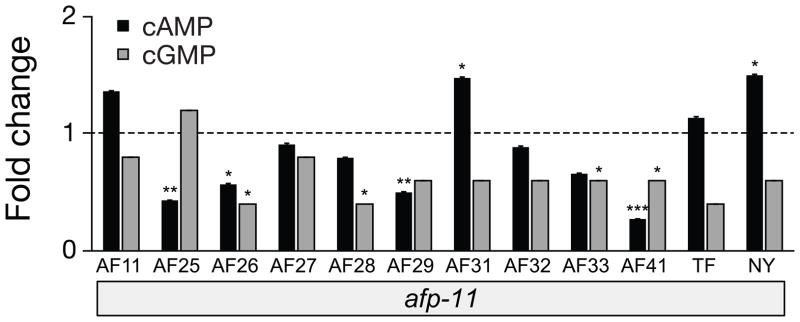

3.2.5 Effects of peptides encoded by afp-11 (AF 11, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 41, and TF and NY)

The effects on cAMP and cGMP produced by the twelve different neuropeptides encoded by afp-11 are shown in Figure 4. These peptides include ten AF peptides, AF11 [3], AF25 [10], and AF26 [10], and the recently discovered peptides AF27, AF28, AF29, AF31, AF32, AF33, AF41, as well as two non-RFamide peptides, TF and NY which are intervening sequences between AF peptides in the AFP-11 precursor protein [42, 51]. These peptides produced multiple classes of responses when injected into A. suum (see also Supplementary Table 1). Peptides AF25, AF26, AF29, and AF41 significantly lowered cAMP. Neuropeptides AF31 and NY slightly elevated cAMP (but not cGMP) and produced low amplitude body waveforms, but these effects on locomotion were less dramatic than those of other neuropeptides that lowered cyclic nucleotides. For example, neuropeptides AF26 (KPNFLRFa) and AF41 (KPNFIRFa) significantly lowered both cyclic nucleotides and caused body wall relaxation.

Figure 4.

cAMP and cGMP responses to injections of the twelve neuropeptides encoded by afp-11. Key observations are that AF25 and AF29 both decrease cAMP; AF26 (KPNFLRFa) and AF41 (KPNFIRFa) decrease both cAMP and cGMP. Neuropeptides AF31 and NY showed slight elevations of cAMP. Standard error bars are shown. Significance (t-test): * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Peptides AF26 and AF41 were investigated further for effects on body length using different concentrations of the peptides. AF26 at higher concentration (100 μM) produces a similarly shaped worm to that of AF41 injected at a lower concentration (5 μM). Immediately after injection of AF41, all of the anteriorly propagating waveforms are abolished and the posture is severely flattened. AF41 injections after AF26 produces the more flattened posture and the effects are long lasting (> 15 minutes) (N= 10 worms; data not shown). Tested at the same concentration, AF26 has a much less dramatic effect in the behavioral assay, as propagating waveforms are still present, although the number of wave crests present is reduced and the wavelength is elongated. These results are notable, in that the sequences of these two neuropeptides only differ in that the isoleucine in AF41 is replaced by leucine in AF26; both peptides are endogenous in A. suum.

Three independent detection techniques, MALDI-TOF MS of single neurons [42], ICC, and ISH [42, 51, 52] indicated localization of neuropeptide AF11 to AVK neurons. The AVK neurons are paired neurons with cell bodies in the ventral ganglion. Their processes traverse the nerve ring and then project posteriorly in the ventral nerve cord; they are ventral cord interneurons.

Previous experiments with related peptides PF1 (SDPNFLRFa) and PF2 (SADPNFLRFa), isolated from Panagrellus redivivus, showed peptide-induced relaxation of A. suum muscle [47, 48]. This relaxation involved hyperpolarization of muscle cells by a mechanism independent of GABA activity.

3.2.6 Effects of peptides encoded by afp-12 (AF36), afp-13 (AF 19, 34, 35, and TT and TL), and afp-14 (AF9)

Afp-12 encodes AF36 (VPSAADMMIRFa), the only predicted peptide product of this precursor protein [6]. AF36 is co-expressed with AF8 and the six peptides encoded by afp-13 in the ALA neuron of the dorsal ganglion. AF36 did not change levels of either cAMP or cGMP nucleotide level (Figure 5) yet produced a flaccid response when it was injected (data not shown).

Afp-13 encodes 6 peptides, all of which have been detected by single-cell MS in the ALA neuron of the dorsal ganglion [6]. Three of these are AF peptides, and the others are either intervening sequences or flanking sequences relative to the AF peptides. Two AF peptides, AF19 (AEGLSSPLIRFa) and AF34 (DSKLMDPLIRFa), which share a C-terminal PLIRFa sequence, produce a marked reduction in cAMP (Figure 5). The third AF peptide, AF35 (DPQQRIVTDETVLRFa), had no effect on cAMP levels. Two of the remaining peptides, peptides TT (TPPEEDLLGRFT) and TL (TNIMGENRLNRNL), produced small but significant increases in cAMP. Small but significant reductions in cGMP levels were induced by AF19 and peptide TL. AF19 and AF34 increased the body length by more than 7% (Table 2) and dramatically inhibited locomotion and locomotory posture (Figure 1).

The afp-14 transcript encodes one copy of AF9 (GLGPRPLRFa), and no other predicted peptide (C. Konop, personal communication). AF9 lowered cAMP, but had no effect on cGMP (Figure 5). Mostly, the body pieces taken for cyclic nucleotide determinations were straight, although sometimes tightly curved at the anterior end near where the injection was made and then dramatically flattened posteriorly. AF9 increased the body length by more than 7% (Table 2) and dramatically inhibited locomotion and obliterated the locomotory posture (Figure 1).

3.2.7 Locus of cAMP and cGMP changes

Previously we concluded that the large AF2-induced elevation of cAMP most probably occurred in muscle [28]. In the experiments reported here, we made no attempt to locate the cellular source of the changes in cAMP or cGMP. The preparations include body wall (cuticle, hypodermis, muscle, excretory canal, and neurons in the nerve cords) and intestine. Cells in any of these tissues might produce the changes in cyclic nucleotides. In C. elegans, the majority of the receptor guanylate cyclases are expressed in sensory neurons in the head [49]. If the receptor guanylate cyclases of A. suum are similarly expressed, these receptors are not present in the region where we sampled.

4 Summary

Instead of using isolated A. suum dissected preparations, the behavior and other bioassays were performed on whole A. suum, modified by ligaturing the head; this induces stereotypical anteriorly propagating body waveforms, and leaves intact the neuromuscular system that generates locomotory behavior. A standard dose of the neuropeptide of interest is injected into the worm. While it is known from other studies that neuropeptides can work in tandem with classical neurotransmitters at the same synapse [50], in the behaving worm any essential co-ligands would have to be supplied by the endogenous system, and it is not clear whether the concentrations are appropriate.

Presumably through a variety of different G protein coupled receptors, cyclic nucleotide levels are regulated by A. suum neuropeptides, and both increases and decreases were seen. Decreases in cAMP correlated with reduced amplitude and/or abolition of waveforms, loss of waveform propagation and increases in body length. Large increases in cAMP are correlated with body contraction and intense jerky thrashing movements (AF2). Neuropeptides AF23, AF26, AF41 and AF19 lower both cAMP and cGMP, and these treatments also produced relaxed linear shaped worms. cGMP is also lowered by TL (afp-13) but the consequence of this on behavior is not obvious.

The changes in cyclic nucleotides we have observed are correlated with the administration of particular peptides, but we do not know whether these effects are direct. Injected peptides might be activating the release of other signaling molecules from cells, and these molecules might be the agonists that affect the cyclic nucleotide levels. Identification and cellular localization of peptide receptors, and the demonstration at the single cell level that cyclic nucleotide levels are changed in that cell by injected peptide, are important goals for future work.

The complete description of neuropeptides present in the A. suum nervous system is essential if we are to understand the role of the nervous system in the organism’s behaviors, and this description is still far from complete. However, the demonstration that the endogenous neuropeptides we have investigated here can disrupt locomotory behavior makes them interesting potential targets for the future development of anthelminthics. Their receptors are in a separate class from those targeted by drugs that affect the cholinergic or GABAergic systems. Peptidergic pathways are thus important in their potential for overcoming genetic drug resistance to the first generation of anthelminthics, many of which affect cholinergic or GABAergic neurotransmission.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH Grant RO1 AI15429. We thank Judith Donmoyer, India Viola, Jessica Jarecki, Katherine Andersen, and Christopher Konop for communicating unpublished results, and Philippa Claude for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Becky Byla, Jason Hummelt, William Marquardt, Diego Calderon, Christopher Konop, and Ben Axt for collecting worms, Bill Feeney for help with the illustrations, and Dave Hoffman for construction of apparatus.

Abbreviations

- AF

Ascaris FMRFamide-like peptide

- afp

Ascaris FMRFamide-like Precursor protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Catharine A. Reinitz, Email: reinitz@wisc.edu.

Anthony E. Pleva, Email: apleva@gilson.com.

Antony O.W. Stretton, Email: aostrett@wisc.edu.

References

- 1.Strand FL. Neuropeptides: regulators of physiological processes. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowden C, Stretton AO. AF2, an Ascaris neuropeptide: isolation, sequence, and bioactivity. Peptides. 1993;14(3):423–430. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(93)90127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowden C, Stretton AO. Eight novel FMRFamide-like neuropeptides isolated from the nematode Ascaris suum. Peptides. 1995;16(3):491–500. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(94)00211-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowden C, Stretton AO, Davis RE. AF1, a sequenced bioactive neuropeptide isolated from the nematode Ascaris suum. Neuron. 1989;2(5):1465–1473. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li C, Kim K. Neuropeptides. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarecki JL, Andersen K, Konop CJ, Knickelbine JJ, Vestling MM, Stretton AO. Mapping neuropeptide expression by mass spectrometry in single dissected identified neurons from the dorsal ganglion of the nematode Ascaris suum. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1(7):505–519. doi: 10.1021/cn1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maule AG, Shaw C, Bowman JW, Halton DW, Thompson DP, Geary TG, et al. KSAYMRFamide: a novel FMRFamide-related heptapeptide from the free-living nematode, Panagrellus redivivus, which is myoactive in the parasitic nematode, Ascaris suum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200(2):973–980. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maule AG, Geary TG, Bowman JW, Marks NJ, Blair KL, Halton DW, et al. Inhibitory effects of nematode FMRFamide-related peptides (FaRPs) on muscle strips from Ascaris suum. Invert Neurosci. 1995;1(3):255–265. doi: 10.1007/BF02211027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yew JY, Davis R, Dikler S, Nanda J, Reinders B, Stretton AO. Peptide products of the afp-6 gene of the nematode Ascaris suum have different biological actions. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502(5):872–882. doi: 10.1002/cne.21357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yew JY, Dikler S, Stretton AO. De novo sequencing of novel neuropeptides directly from Ascaris suum tissue using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight/time-of-flight. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17(24):2693–2698. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yew JY, Kutz KK, Dikler S, Messinger L, Li L, Stretton AO. Mass spectrometric map of neuropeptide expression in Ascaris suum. J Comp Neurol. 2005;488(4):396–413. doi: 10.1002/cne.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C, Kim K, Nelson LS. FMRFamide-related neuropeptide gene family in Caenorhabditis elegans. Brain Res. 1999;848(1–2):26–34. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01972-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McVeigh P, Alexander-Bowman S, Veal E, Mousley A, Marks NJ, Maule AG. Neuropeptide-like protein diversity in phylum Nematoda. Int J Parasitol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McVeigh P, Leech S, Mair GR, Marks NJ, Geary TG, Maule AG. Analysis of FMRFamide-like peptide (FLP) diversity in phylum Nematoda. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35(10):1043–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nathoo AN, Moeller RA, Westlund BA, Hart AC. Identification of neuropeptide-like protein gene families in Caenorhabditiselegans and other species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(24):14000–14005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241231298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brownlee DJ, Fairweather I, Holden-Dye L, Walker RJ. Nematode neuropeptides: Localization, isolation and functions. Parasitol Today. 1996;12(9):343–351. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)10052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cowden C, Sithigorngul P, Brackley P, Guastella J, Stretton AO. Localization and differential expression of FMRFamide-like immunoreactivity in the nematode Ascaris suum. J Comp Neurol. 1993;333(3):455–468. doi: 10.1002/cne.903330311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K, Li C. Expression and regulation of an FMRFamide-related neuropeptide gene family in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Comp Neurol. 2004;475(4):540–550. doi: 10.1002/cne.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sithigorngul P, Cowden C, Stretton AO. Heterogeneity of cholecystokinin/gastrin-like immunoreactivity in the nervous system of the nematode Ascaris suum. J Comp Neurol. 1996;370(4):427–442. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960708)370:4<427::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sithigorngul P, Stretton AO, Cowden C. Neuropeptide diversity in Ascaris: an immunocytochemical study. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294(3):362–376. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White J, Southgate E, Thomson N, Brenner S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode C. elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1986;314:1–340. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stretton A, Donmoyer J, Davis R, Meade J, Cowden C, Sithigorngul P. Motor behavior and motor nervous system function in the nematode Ascaris suum. J Parasitol. 1992;78(2):206–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis RE, Stretton AO. The motornervous system of Ascaris: electrophysiology and anatomy of the neurons and their control by neuromodulators. Parasitology. 1996;113 (Suppl):S97–117. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000077921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis RE, Stretton AO. Structure-activity relationships of 18 endogenous neuropeptides on the motor nervous system of the nematode Ascaris suum. Peptides. 2001;22(1):7–23. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00351-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fellowes RA, Maule AG, Marks NJ, Geary TG, Thompson DP, Shaw C, et al. Modulation of the motility of the vagina vera of Ascaris suum in vitro by FMRF amide-related peptides. Parasitology. 1998;116 ( Pt 3):277–287. doi: 10.1017/s0031182097002229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holden-Dye L, Brownlee DJ, Walker RJ. The effects of the peptide KPNFIRFamide (PF4) on the somatic muscle cells of the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120(3):379–386. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purcell J, Robertson AP, Thompson DP, Martin RJ. PF4, a FMRFamide-related peptide, gates low-conductance Cl(−) channels in Ascaris suum. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;456(1–3):11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinitz CA, Herfel HG, Messinger LA, Stretton AO. Changes in locomotory behavior and cAMP produced in Ascaris suum by neuropeptides from Ascaris suum or Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;111(1):185–197. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00317-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verma S, Robertson AP, Martin RJ. The nematode neuropeptide, AF2 (KHEYLRF-NH2), increases voltage-activated calcium currents in Ascaris suum muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151(6):888–899. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanfleteren JR, Van de Peer Y, Blaxter ML, Tweedie SA, Trotman C, Lu L, et al. Molecular genealogy of some nematode taxa as based on cytochrome c and globin amino acid sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1994;3(2):92–101. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1994.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sithigorngul P, Jarecki JL, Stretton AOW. A specific antibody to neuropeptide AF1 (KNEFIRFamide) recognizes a small subset of neurons in Ascaris suum: differences from Caenorhabditis elegans. J Comp Neurol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cne.22584. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nanda JC, Stretton AO. In situ hybridization of neuropeptide-encoding transcripts afp-1, afp-3, and afp-4 in neurons of the nematode Ascaris suum. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(6):896–910. doi: 10.1002/cne.22251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowman JW, Friedman AR, Thompson DP, Ichhpurani AK, Kellman MF, Marks N, et al. Structure-activity relationships of KNEFIRFamide (AF1), a nematode FMRFamide-related peptide, on Ascaris suum muscle. Peptides. 1996;17(3):381–387. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowman JW, Friedman AR, Thompson DP, Maule AG, Alexander-Bowman SJ, Geary TG. Structure-activity relationships of an inhibitory nematode FMRFamide-related peptide, SDPNFLRFamide (PF1), on Ascaris suum muscle. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32(14):1765–1771. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brownlee DJ, Walker RJ. Actions of nematode FMRFamide-related peptides on the pharyngeal muscle of the parasitic nematode, Ascaris suum. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;897:228–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson DP, Davis JP, Larsen MJ, Coscarelli EM, Zinser EW, Bowman JW, et al. Effects of KHEYLRFamide and KNEFIRFamide on cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels in Ascaris suum somatic muscle. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33(2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Croll NA. Behavioural analysis of nematode movement. Adv Parasitol. 1975;13:71–122. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croll NA. The behaviour of nematodes: their activity, senses and responses. London: Edward Arnold; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reinitz CA, Stretton AO. Behavioral and cellular effects of serotonin on locomotion and male mating posture in Ascaris suum (Nematoda) J Comp Physiol A. 1996;178(5):655–667. doi: 10.1007/BF00227378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edison AS, Messinger LA, Stretton AO. afp-1: a gene encoding multiple transcripts of a new class of FMRFamide-like neuropeptides in the nematode Ascaris suum. Peptides. 1997;18(7):929–935. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(97)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nanda J. Ascaris suum. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2004. Molecular biological analysis of neuropeptide transcripts from the nematode. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarecki JL. Identification and localization of neuropeptides in Ascaris suum by mass spectrometry. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dossey AT, Reale V, Chatwin H, Zachariah C, deBono M, Evans PD, et al. NMR analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans FLP-18 neuropeptides: implications for NPR-1 activation. Biochemistry. 2006;45(24):7586–7597. doi: 10.1021/bi0603928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horton JK, Martin RC, Kalinka S, Cushing A, Kitcher JP, O’Sullivan MJ, et al. Enzyme immunoassays for the estimation of adenosine 3′,5′ cyclic monophosphate and guanosine 3′,5′ cyclic monophosphate in biological fluids. J Immunol Methods. 1992;155(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maule AG, Bowman JW, Thompson DP, Marks NJ, Friedman AR, Geary TG. FMRFamide-related peptides (FaRPs) in nematodes: occurrence and neuromuscular physiology. Parasitology. 1996;113 (Suppl):S119–135. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000077933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franks CJ, Holden-Dye L, Williams RG, Pang FY, Walker RJ. A nematode FMRFamide-like peptide, SDPNFLRFamide (PF1), relaxes the dorsal muscle strip preparation of Ascaris suum. Parasitology. 1994;108 ( Pt 2):229–236. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000068335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holden-Dye L, Franks CJ, Williams RG, Walker RJ. The effect of the nematode peptides SDPNFLRFamide (PF1) and SADPNFLRFamide (PF2) on synaptic transmission in the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum. Parasitology. 1995;110 ( Pt 4):449–455. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000064787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ortiz CO, Etchberger JF, Posy SL, Frokjaer-Jensen C, Lockery S, Honig B, et al. Searching for neuronal left/right asymmetry: genomewide analysis of nematode receptor-type guanylyl cyclases. Genetics. 2006;173(1):131–149. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.055749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fioravante D, Smolen PD, Byrne JH. The 5-HT- and FMRFa-activated signaling pathways interact at the level of the Erk MAPK cascade: potential inhibitory constraints on memory formation. Neurosci Lett. 2006;396(3):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viola IR. Comparing the cellular localization of Ascaris neuropeptides using immunocytochemistry, molecular biology and mass spectrometry. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersen KM. Development of single neuron mass spectrometry in Ascaris suum. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.