Loose bodies (“joint mice”) in joints have long been recognized. According to Nagura [4], Monroe described “pea-sized arthrophytes in the knee and in a cavity corresponding to the arthrophyte in the lateral condyle of a female corpse, (and) ascribed the origin of the arthrophytes to trauma.” He also stated that Laennec, writing on joint mice in 1817, espoused the view that loose bodies were not related to trauma, but a “proliferation of the cartilage of the periarticular synovial tissue.” On the other hand, Broca, in 1854, suggested loose bodies arose from spontaneous necrosis of a part of the articular surface. (I have been unable to confirm these three references and they are not cited among Nagura’s 104 references.) Regardless of the cause, it is clear loose bodies were well recognized in the first half of the 19th Century [1]. Perhaps König best described and established Broca’s theory that loose bodies arose from pieces of articular cartilage that broke loose from articular surface, and coined the term “osteochondritis dissecans” [2]. His observations came from operations on three patients.

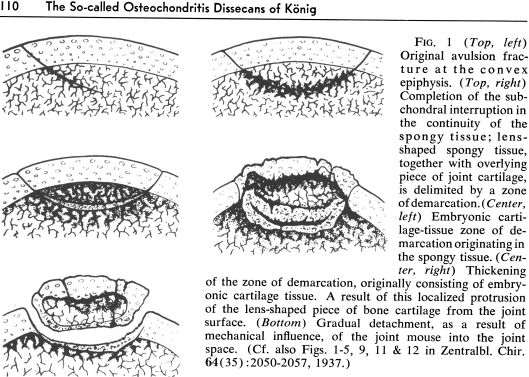

Nagura, who had written on osteochondritis as early as 1937 [3], described the various theories – and disagreements between authors – in some detail, and provided extended quotations from some of the late 19th and early 20th Century writers. He showed the radiographic and gross appearances at surgery were indeed consistent with separation of the articular cartilage and/or subchondral bone with attempts to repair (Fig. 1). He produced experimental “interruption in the continuity of subchondral bone” and showed similar findings [3]. Based on his 59 clinical cases, experimental studies, and review of the literature, Nagura concluded osteochondritis dissecans arose from repeated and successive minor interruptions in the subchondral bone with subsequent cartilaginous repair and sometimes separation of a fragment that was incompletely healed to the subjacent bone and/or cartilage, and that it did not arise as a result of spontaneous necrosis. To this day, the argument of the origin is unsettled.

Fig. 1.

The figure shows Nagura’s description of the origin of osteochondritis dissecans. (Reprinted with permission and © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, from Nagura S. The So-called Osteochondritis Dissecans of König. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1960;18:100–118.)

References

- 1.Catalogue of The Hunterian Collection in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London: Part 1. Comprehending The Pathological Preparations in Spirit. London: Richard Taylor; 1830.

- 2.König F. Über freie Körper in Gelenken [On free bodies in joints] Dtsch Z Chir. 1887;27:90–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02792135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagura S. Das Wesen und die Enstehung der Osteochondritis dissecans Königs (bzw. der Perthes, Köhler II- und der ähnlichen Krankheiten und Veränderungen an wachsended Knochenenden [The Nature and Origin of osteochondritis dissecans of König (or Perthes, Köhler II and similar diseases and changes in growing ends of bones. Zentralbl Chir. 1937;62:2049. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagura S. Problem of so-called osteochondritis of the femur head [In German] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1959;91:224–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]