Abstract

Many youth experience ongoing trauma exposure, such as domestic or community violence. Clinicians often ask whether evidence-based treatments containing exposure components to reduce learned fear responses to historical trauma are appropriate for these youth. Essentially the question is, if youth are desensitized to their trauma experiences, will this in some way impair their responding to current or ongoing trauma? The paper addresses practical strategies for implementing one evidence-based treatment, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) for youth with ongoing traumas. Collaboration with local therapists and families participating in TF-CBT community and international programs elucidated effective strategies for applying TF-CBT with these youth. These strategies included: 1) enhancing safety early in treatment; 2) effectively engaging parents who experience personal ongoing trauma; and 3) during the trauma narrative and processing component focusing on a) increasing parental awareness and acceptance of the extent of the youths’ ongoing trauma experiences; b) addressing youths’ maladaptive cognitions about ongoing traumas; and c) helping youth differentiate between real danger and generalized trauma reminders. Case examples illustrate how to use these strategies in diverse clinical situations. Through these strategies TF-CBT clinicians can effectively improve outcomes for youth experiencing ongoing traumas.

Keywords: children, adolescents, Trauma-Focused CBT, ongoing traumas, domestic violence, community violence

Introduction

A number of evidence-based treatments are now available to treat children who experience trauma (www.nctsn.org). This paper focuses on one such manualized, evidence-based treatment for maltreatment-related traumatic stress responses, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT, Cohen, Mannarino & Deblinger, 2006; www.musc.edu/tfcbt). TF-CBT includes components to enhance youth resiliency-based coping skills, actively includes parents or caregivers in treatment, and develops trauma narratives and cognitively processes the youth’s personal trauma experiences. Many neurobiological systems change in response to child trauma experiences (DeBellis et al, 1999; b; Cohen, Perel, DeBellis, Friedman & Putnam, 2002) and are often manifested as problems with sleep, concentration, irritable outbursts, or somatic symptoms. Current knowledge is lacking about the impact of treatment on these biological-based vulnerabilities, or the interaction of therapy and repeated trauma on reversing these changes. For past traumas, relaxation, affective modulation and in vivo strategies are typically implemented to address biological-based hyperarousal symptoms (e.g., physiological reactivity to trauma cues; hypervigilance or over-attention to environmental threat detection etc.). Parental support contributes significantly to success. Youth experiencing ongoing trauma may not be able to successfully apply coping strategies until they are able to differentiate between historical danger, realistic present danger, and over-generalized trauma reminders. The process of creating a trauma narrative is often critical to providing youth with the ability to make these distinctions. Trauma-focused treatments such as TF-CBT impart skills useful for coping with ongoing trauma, including awareness of and increased ease with coping with ongoing trauma reminders and recognizing traumatic responses. This may prove important to professionals in providing continuity of care, as well as reporting re-abuse that occurs in these youth.

Therapists often provide TF-CBT to children who have experienced past traumas such as child abuse or neglect, traumatic losses, or multiple previous traumas. However, many children experience ongoing traumas. Various forms of violence may be new or newly detected after TF-CBT treatment initiation. Typical types of ongoing traumas are domestic, community and school violence. For example, maltreated youth are at increased risk for high school bullying victimization (e.g., Mohapatra, Irving, Pagia-Boak, Wekerle, Adlaf & Rehm, 2010), which may include sexual harassment and physical attack, as well as the more common psychological abuse (verbal abuse; rumor-spreading; ostracizing etc.). These potentially traumatic events are similar to child maltreatment in some ways (e.g., all tend to be chronic; all may have multiple perpetrators), and may re-surface prior posttraumatic stress responses. However domestic, community or school violence differ from child maltreatment in that no formal system exists to protect children from the former types of traumas. As a result, they rarely if ever result in legal child protective action or prosecution. Thus, beyond any protection families themselves can provide, few if any, external forces prevent these traumas from continuing. In a recent study of youth receiving treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms related to their mothers’ domestic violence, more than half of their mothers acknowledged that their youth continued to have ongoing contact with the perpetrators; youth themselves reported more frequent contact with the perpetrators, with 40% acknowledged repeated trauma exposure during treatment (Cohen, Mannarino & Iyengar, 2011). Clearly, ongoing risk to the youth remains. Despite mandated reporting requirements and child protective services, child abuse may also reoccur during therapy. Two international studies of HIV affected sexually abused youth indicated that more than half of these youth lived with families where there were domestic violence perpetrators, and almost half (48%) had ongoing contact with their sexual abuse perpetrator (Murray, Skavenski, Familiar, Bass, Bolton & Jere, 2010 Murray; Semrau, Familiar, Scott, Johnson, Thea et al, 2011). This level of risk to the youth is problematic for their healthful development and severely challenges resilience processes (e.g., Cichetti, Rogosch, Sturge-Apple & Toth, 2010).

Mental health therapists often ask whether evidence-based, trauma-focused treatments such as TF-CBT are appropriate and helpful for youth who experience ongoing traumas. In particular, therapists are concerned about using the exposure-based components (e.g., gradual exposure; trauma narration and cognitive processing of traumatic experiences), which are typically used to gain mastery over memories and reminders about past traumatic experiences. Therapists question how youth can benefit from these exposure-based interventions that are supposed to “de-sensitize” youth to their past traumatic memories and experiences, if they are simultaneously experiencing repeated traumas in real life and thus being repeatedly re-sensitized to the same types of traumas. How exactly is TF-CBT used for these youth and is there any evidence that it works for these youth?

We have been conducting a series of TF-CBT treatment studies in the U.S. and Zambia for children who were exposed to ongoing traumas including domestic violence (U.S.) and multiple traumas related to domestic violence and HIV/sexual abuse (Zambia). Collaborative efforts between the authors, community/local therapists, and family members have helped us to develop practical strategies for implementing TF-CBT for these youth. The purpose of this paper is to share the practical strategies learned from these efforts, and to address the above concerns of therapists who are trying to help youth who are exposed to ongoing traumatic experiences. Youth experiencing ongoing traumas often have little time to reflect upon these experiences before the next trauma occurs. It is exceedingly difficult to see oneself and one’s situation clearly while still being immersed within that situation. It is, therefore, important to help these youth to develop coherent narratives or self-stories with adaptive cognitions and contextualization even in the context of ongoing traumas. TF-CBT is an intervention designed to achieve these goals, and additional attention is needed when ongoing trauma is detected.

TF-CBT Application for Past Traumas

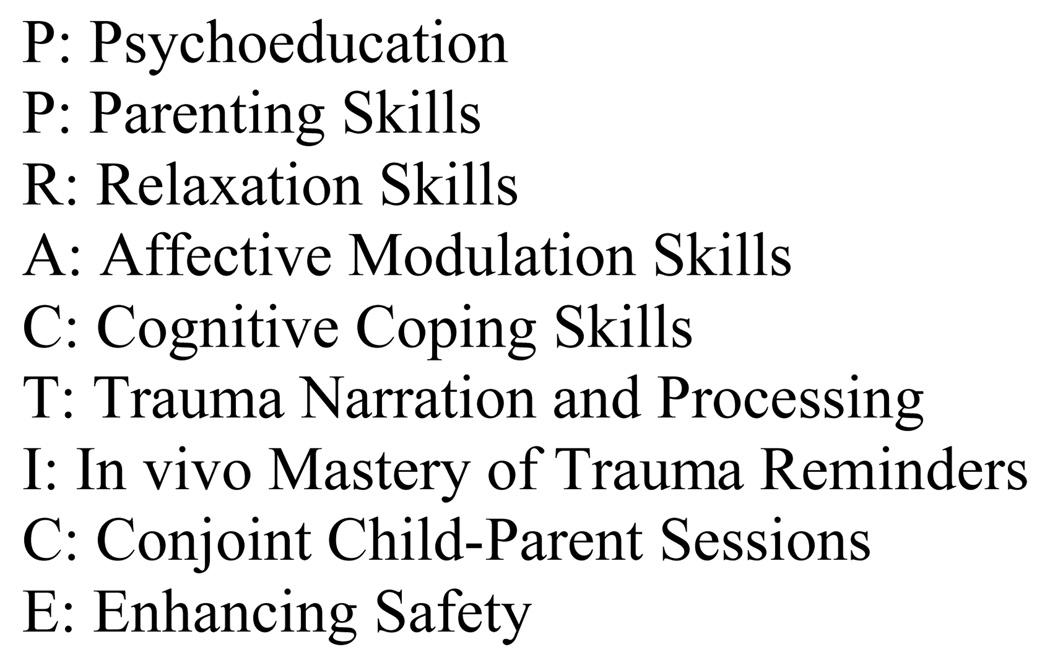

In order to most clearly describe how these strategies are different, we briefly describe a case example, to illlustrate how TF-CBT is typically implemented for a youth who experienced past traumas. TF-CBT components and their typical application for past traumas are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

TF-CBT Components for Past Traumas

Case example

Maya,1 a 12 year old girl, experienced sexual abuse from approximately 5–9 years old by her biological father who is now incarcerated. Maya presented to treatment initiated by her foster mother’s concerns about angry outbursts and trouble at school. During the assessment, Maya acknowledged intrusive thoughts about the sexual abuse which triggered anger and shame, attempts to avoid remembering the abuse, anger at her biological mother for not believing her about the abuse (which led to her placement in foster care), difficulty concentrating in school, and difficulty sleeping at night.

Treatment began with a focus on psychoeducation in which the therapist validated Maya’s problems as being sexual abuse-related rather than “bad” behavior or characterological issues. At first the foster mother was dubious about the connection between Maya’s trauma and her current behavior problems, but she knew no details of Maya’s trauma history that would help her understand this. Initially, Maya was hesitant about foster mother knowing about her sexual abuse, but agreed to let the therapist share this with the foster mother in a parent session. The foster mother expressed shock when the therapist told her about what Maya had experienced. After this session the foster mother assured Maya that she believed her, and that no one would hurt her in foster mother’s home. With the knowledge, the foster mother was able show increased levels of support and compassion, and this was very important to the positive outcome of therapy.

The therapist helped Maya and her foster mother gain a better understanding of external and internal cues that reminded Maya of her past sexual abuse (“trauma reminders”). For example, Maya got really mad when she saw “happy families,” especially girls with their fathers, suggesting that children have traumatic responses to what they experienced, as well as what they failed to experience knowing normative expectations for families. Maya also had angry outbursts at school when she was in class with boys who talked loudly, and used certain rude words that reminded her of things that her father said to her during his violent attacks. These situations made Maya have intrusive memories during class time (i.e., memories of what her parents did to her appeared involuntarily into her consciousness). Taken together, these provocations triggered anxious feelings and generalized fears that someone might hurt her again. The therapist helped Maya develop specific relaxation and grounding activities (i.e., focusing on being in the “here and now”). Also, cognitive coping skills were taught to challenge the belief that “it will happen again now”, and encouraged the foster mother to help initiate and reinforce Maya’s use of these skills. Specific relaxation strategies and bedtime routines were also implemented to help Maya sleep at night. Foster mother worked with Maya to assure her of her current safety, particularly at nighttime, as that was when her father used to sexually abuse Maya, as is common in incest. As Maya implemented these skills and no further traumas occurred, she gradually gained increasing mastery over the past trauma reminders. An in vivo exposure plan helped Maya gradually master her nighttime fears. Foster mother worked with Maya’s teacher, who helped Maya use affective modulation strategies at school. Through practicing her newly acquired skills when she experienced reminders, Maya became increasingly able to master these reminders, to maintain focus on her school work, and to control aggressive responding to internal and external cues.

The therapist then helped Maya to create a trauma narrative about her personal abuse experiences. Maya started by describing her family before the abuse began, including positive memories of both parents. She described several episodes of sexual abuse by her father, her belief that mother would rescue her once she told, and her hurt and anger at mother’s betrayal. Through this process, the therapist was able to identify and process several maladaptive cognitions (e.g., “I should have been able to stop him from abusing me;” “Why didn’t I tell my mom earlier, maybe she would have believed me then?”). Verbalizing these memories further concretized for Maya that she had already lived through these experiences and that they had occurred in the past. The therapist shared the narrative with the foster mother in parallel parent sessions, allowing the foster mother to develop a clearer understanding of Maya’s trauma experience. Through this process, the foster mother provided more meaningful support to Maya that, in turn, reinforced Maya’s belief in her current safety with the foster mother.

During conjoint sessions Maya directly shared the narrative with the foster mother, and received the foster mother’s praise for her courage and skills to cope with these experiences. Together with the therapist, they addressed skills to enhance Maya’s future safety (e.g. recognizing potential trauma triggers when she was ready to start dating; developing drug refusal skills, how to select safe dating partners, staying safe from sexual predators in the future, etc). At TF-CBT closure, Maya had largely learned how to cope successfully with trauma reminders. Although she still experienced these reminders on occasion, Maya understood that the traumas themselves occurred in the past and that she was now safe.

Differences between past and ongoing traumas: Key issues for TF-CBT adaptation

There are three key issues to be recognized for TF-CBT use where there is risk for ongoing trauma to the youth. The first difference between past and ongoing traumas is the degree to which youth, their parents and therapists can realistically count on the youth’s ongoing safety. As evident in the above case example, Maya initially did not believe she was safe from future abuse; however, her therapist could realistically address these maladaptive cognitions because Maya’s current environment was no longer dangerous. When Maya experienced trauma reminders such as hearing boys at school talk like her father, she could realistically remind herself that they were not her father, and that she was safe from ongoing sexual abuse by her father. In contrast, when traumas are ongoing, the therapist needs to validate safety concerns and proactively help the youth and parent to develop realistic safety contingencies that are consistent with the individual youth’s developmental abilities and living situation.

A second difference between past and ongoing traumas is often the degree to which the non-offending parent or primary caregiver (hereafter referred to as “parent”) is able to protect to the youth, and how this affects the parent’s self-view. Where a parent’s protection efficacy remains challenged, that parent’s acceptance, acknowledgement, and validation of the youth’s experiences and related problems may often be similarly challenged. Although parents may feel guilt and self-blame about a youth’s previous traumas, failure to protect in the past or the youth's behavior problems parents can also reassure themselves that they are currently protecting the youth from trauma and assuring the youth’s safety. For example, once Maya’s foster mother saw herself as a critical “protective shield” to Maya, she stopped thinking that she was a failure as a foster parent and re-focus her efforts on protecting a vulnerable youth. In contrast, parents have much greater difficulty viewing himself or herself as protecting when there is ongoing trauma. This may be particularly true for parents who make decisions that place the child in harm’s way (e.g., staying with a partner who is perpetrating domestic violence). These parents may feel guilty, ashamed, defensive about their choices, depowered by their current romantic situation, and not being in a psychological or economic position to perceive that alternative action is an option. Some of these parents minimize, invalidate or deny the youth’s traumatic experiences. Parents who are themselves experiencing ongoing trauma, or may have personal, unresolved traumatic histories, may be unavailable to support the child due to their own trauma or depressive symptoms. This can be especially challenging since, unlike other treatments, TF-CBT involves youth directly describing their personal trauma experiences and parents directly hearing these narratives from their child. Since parental support is a strong mediator of positive child outcomes during TF-CBT treatment (Cohen & Mannarino, 1996; 2000), it is critical to enhance parental engagement while addressing parental shame or self-blame.

A third difference is the degree to which youth are able to engage in perspective-taking and contextualizing. The multiple goals of narrative include mastery of learned avoidance and fear, as well as to gain more accurate cognitions and perspectives about traumatic experiences and place them within the broader context of one’s life. Due to the heightened emotional arousal and diminished cognitive and verbal functioning associated with acute trauma exposure, individuals cannot develop coherent trauma narratives during these episodes. Youth who are no longer being traumatized have the opportunity to contrast their past traumatic experiences with their current experiences of relative safety. No longer living in the trauma context allows youth to gain perspective and meaning in a reflective manner about how the past traumas have impacted their lives. Maya was able to think about her previous sexual abuse from the perspective of currently living in a safe environment where her caregiver believed and supported her. This helped her to both grieve her parents’ inability to protect her and acknowledge her hope for some form of reconciliation with them in the future—ideas that would have made her feel far too vulnerable earlier.

Collaborative Projects Implementing TF-CBT for Ongoing Traumas

The strategies described here were developed through collaboration with families (youth and parents), community therapists and other professionals providing services to these families in two settings. The Children Recover after Family Trauma (CRAFT) Project was conducted from 2004–2009 to evaluate the effectiveness of TF-CBT compared to usual child treatment in a community domestic violence center, the Women’s Center and Shelter of Greater Pittsburgh (WCS) (Cohen, Mannarino & Iyengar, 2011). The project involved receiving initial and ongoing input from the WCS Executive director, clinical director, child supervisor, child therapists, and family members regarding how TF-CBT should be implemented for youth and mothers who experienced domestic violence including ongoing domestic violence Additional meetings took place between the child therapists, directors and child supervisor and the first author (JAC) regarding additional changes that needed to be made to the model As treatment proceeded, we solicited both verbal and written input from mothers. Tailoring TF-CBT to this ongoing trauma risk remains an empirical effort.

The Zambia Project was conducted from 2006–2009 in Lusaka to evaluate the feasibility of training and implementing TF-CBT with national lay workers to treat children who had experienced sexual abuse and other traumatic experiences. This project employed multiple collaborative steps. A local qualitative study was conducted first to identify problems and symptoms from the communities’ perspective (Murray, Haworth, Semrau, Singh, Aldrovandi, Sinkala et al. 2006). Focus groups were held with local stakeholders to discuss the results of the qualitative study, review intervention options, and eventually discuss TF-CBT and its application in Zambia. National counselors were trained in TF-CBT by the third author (LKM), during which discussions took place about the cross-cultural applicability of each component (Murray, Skavenski, Jere, Kasoma, Imasiku, Hupunda, et al., 2011). The counselors continued giving feedback throughout their local “practice sessions,” where they would practice role-playing the different components in two local languages (Nyanja and Bemba). As national counselors took on cases, written and verbal reports were given describing how the model should be and was being applied in Zambia (e.g., additional time in psychoeducation explaining how TF-CBT was different from “counseling,” as understood by most in Zambia which is 1 – 2, 15 minute sessions of advice giving).

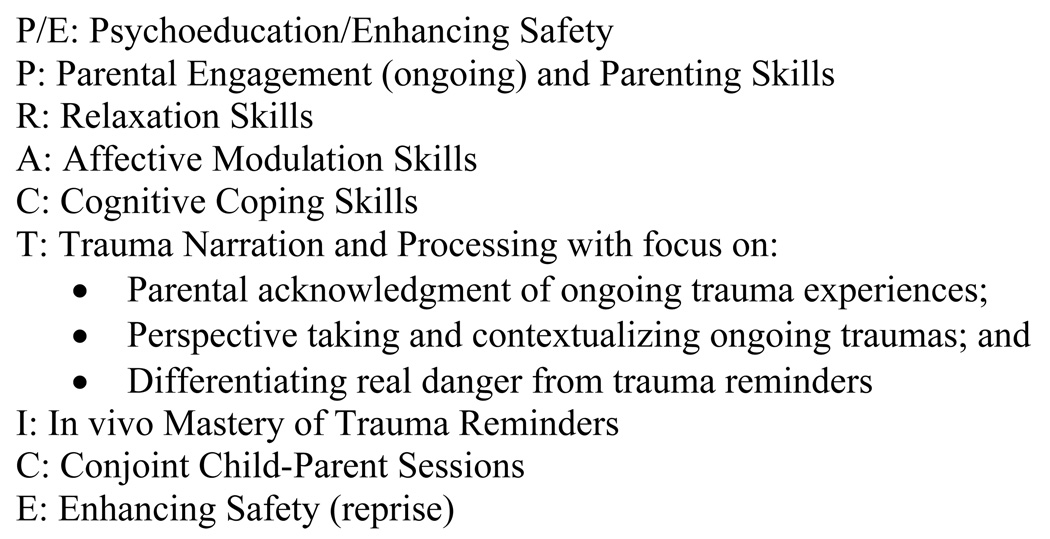

Using these strategies in the CRAFT Project, youth exposed to domestic violence who received TF-CBT experienced significantly greater improvement in anxiety and PTSD symptoms and PTSD diagnosis than those who received child centered therapy. Incorporating these strategies into TF-CBT treatment also led to significant improvement in PTSD and shame among youth experiencing domestic violence, sexual abuse and multiple traumas in the Zambia projects (Murray, Skavenski, Familiar, Bass, Bolton, Jere, 2010;Murray, Skavenski, Michalopoulos, Bolton, Bass, Cohen, 2011). It is noteworthy that the most improvement occurred in the very areas that some therapists express the most doubt about. Despite the possibility that youth would experience repeated re-sensitization due to repeated trauma exposure, the CRAFT Project documented that youth experienced the greatest improvement in PTSD avoidance and PTSD hyperarousal (Cohen et al, 2011), suggesting that with the above strategies TF-CBT can effectively reverse maladaptive trauma responses even in the face of repeated trauma exposure. Importantly, youth receiving TF-CBT also experienced significantly fewer serious adverse events such as re-abuse, psychiatric hospitalization or repeated episodes of domestic violence. The TF-CBT application for ongoing trauma are summarized in Figure 2 and described in detail in the sections that follow.

Figure 2.

TF-CBT Components for Ongoing Trauma Exposure

TF-CBT Strategy #1: Enhancing Safety Early in Treatment

From the start of both of the above projects, addressing safety early in treatment was identified as a priority for youth experiencing ongoing traumas by several stakeholders. The first application was to move the Enhancing Safety component to the start of treatment as depicted in Figure 2. Therapists begin to implement this component at the outset of treatment by assessing children’s immediate risk for repeated trauma exposure. This can be a daunting and sensitive task. For example, in the CRAFT Project therapists asked mothers each week how much contact youths had with the domestic violence perpetrator during the prior week. A mother might report that the youth had not seen the perpetrator at all during the previous week, but the youth might mention during his individual session that the family was living with the perpetrator. These situations present challenges to safety planning, as well as to maintaining engagement with the mother. The therapist needs to address both the risk posed by the presence of the perpetrator and that posed by the youth’s disclosure (i.e., will the youth face negative consequences for revealing this?) In our jurisdiction (Pennsylvania), domestic violence is not a form of child abuse, so the therapist can assure the mother that she has no negative judgment about the mother in this regard and is only asking in order to engage in appropriate safety planning since this partner previously perpetrated violence in the home. In the Zambia project, addressing safety early in treatment was also seen as critical. As with many low-resource countries, there is usually no mental health infrastructure to afford families’ shelters or protection services. In addition, the situation was complicated by the fact that often the perpetrators were the bread-winners in the family system, and thus represented the livelihood of the family. National counselors followed the same process as described above.

Safety planning in the context of ongoing traumas depends on several factors, including the nature and severity of danger involved in the trauma; the youth’s developmental level and ability to carry out concrete safety plans, the non-offending parent’s availability and ability to serve as a source of safety (e.g., if the mother is the direct victim of domestic violence, she will likely be unable to do so since she will likely be under direct attack when the violence is occurring); and the availability of other individuals who can serve as backup sources of safety for the youth. The therapist must take all of these factors into consideration when helping the youth and mother to develop a feasible safety plan. Younger children are more dependent on adults for protection, and safety plans must take into account individual developmental, cognitive and emotional factors as well as the abilities of the adults to protect the child. In addition to obvious physical factors (young children are not as fast, smart or coordinated as adults and usually cannot escape, elude or call for help), they also may not be capable of fully grasping the reality and implications of the danger. For these children providing a concrete behavioral plan with in-session role play, practice at home, rewards for following the plan and clear consequences for non-compliance, while acknowledging the child’s attachment to the parent, is more effective than trying to use logic to explain the plan to the child. Youth experiencing community violence and their parents may perceive that their entire environment is dangerous and that there is no way to stay safe. Therapists work with these youth and their parents to identify any safe places, people and settings that may exist even within the most dangerous communities. Identifying churches, mosques or faith-based organizations, neighborhood watch organizations, schools, YMCA or other community organizations, relatives’ and neighbors’ apartments or homes where the youth can seek refuge if there is an episode of sudden violence on the way to or from school or in other unexpected situations can help youth and parents recognize that although the danger may be ubiquitous, safety is also available. Youth and parents plan alternative routes to places they might go, with several “safe” places along the way. Therapists may also practice specific safety strategies if the youth were to encounter someone with a weapon (e.g., hiding, lying still) in order to help the youth feel more empowered in these scenarios.

One of the initial questions that therapists often ask when the youth continues to live with the perpetrator is whether directly discussing the violence in therapy has the potential to pose added risks to the child. For example, if the perpetrator is the father and the child is very young, very emotionally attached to the father and/or the father is so focused on quashing attempts that may lead to the mother and child leaving that he demands to know everything that goes on during the child’s therapy, the child may tell the father details of what is being discussed during trauma-focused therapy. This may provoke increased violence, including toward the child for describing the father’s abusive behaviors to an “outsider” (i.e., the therapist). Therapists often ask how to balance the potential benefits and risks of TF-CBT in these circumstances. We have found that it is often helpful in these situations to obtain permission from the mother to contact the father via phone to explain the purpose of the treatment. This typically decreases the father’s need to obtain information directly from the child about the content of treatment. When the therapist initiates such contact, openly tells the father about TF-CBT (e.g., describing it in terms of improve the child’s symptoms related to family issues), and offers to speak with the father if he has questions in the future, this often mitigates the father’s need to elicit or coerce information directly from the child on an ongoing basis. Below are three case examples depicting the complex situations where violence continues. The TF-CBT work in these cases focused on the goals of enhancing child safety, recognizing the reality that it is a process towards family-wide safety and living security.

Case example 1

Trina, a 10 year old child in Zambia, experienced ongoing domestic violence at home. The father became physically violent towards Trina as well as her younger sister during these episodes. During the first session with mother, the therapist validated mother’s distress and praised mother’s courage for being willing to support Trina during TF-CBT since mother knew that Trina would be talking about mother’s domestic violence experiences and this might be difficult for mother. Mother said that she was willing to do this in order to help her child, but that they depended on the money the father made for surviving. The therapist addressed mother’s desire to protect her children from the violence at home, and this led to brainstorming about specific strategies that the mother and Trina might take to protect Trina and her younger sister. Trina, her mother and the therapist met together, and the therapist asked questions to try to help Trina and her mother identify signs just before the abuse occurred. Trina and mother both said that father drank a lot and that this was usually when he became angry and abusive. They agreed that if father stayed out after 8 PM this was a “bad sign” that there may be trouble later that night, because he was probably out drinking at a bar. Trina and her mother agreed that if father had not come home by 8 PM, Trina would take her little sister and go sleep next door with her “auntie” (a term used in Zambia for someone close to the family, whether actually part of the family or a neighbor). The therapist asked whether mother might also go next door in order to avoid the violence, but mother said that this would be too dangerous because when father came home, if he found that mother was not there he would come looking for her at the auntie’s house and the girls would then be in just as much danger as if they had stayed at home. Trina started implementing this plan and began to feel safer over time. Although she continued to experience occasional episodes of domestic violence at other times, and she knew that her mother continued to be victimized on a regular basis, she now said “I can keep me and my sister safe”. Her mother also felt empowered by being able to more effectively protect her children.

Case example 2

Luwi, a 13 year old Zambian girl was staying with her aunt who was supportive and participating in the TF-CBT treatment with her (both of the girl’s parents had died of AIDS). However, her uncle was often verbally abusive of Luwi and treated her “like a 2nd class citizen” (a phrase commonly used with HIV orphans living with other family members). Luwi shared with the therapist that her uncle came home during the day (when aunt was at work) with alcohol on his breath. At these times the uncle would often try to sexually abuse her. He had never actually molested her, but Luwi was frightened that she would get pregnant or contract HIV, and be forced to leave aunt’s home just as she had been forced to leave her previous aunt’s home when she disclosed sexual abuse by her other uncle. She did not want to tell her aunt about her uncle’s behavior because Luwi did not want to risk her aunt getting angry at her, or not believing her. Luwi summarized her situation: “I don’t have any other family to live with, I will have to live on the streets.” The therapist believed that the aunt would be supportive, but Luwi said that she would run away before telling the aunt about her uncle. The therapist was concerned that the danger of Luwi running away was imminent and real, so agreed not to discuss what was occurring with the aunt. The therapist and Luwi developed the strategy that if the uncle came home with alcohol on his breath during the day when the aunt was at work, Luwi would say that she had to go to the market in order to fix him something to eat. She would then leave and not return until her aunt had returned home. Luwi practiced this strategy with the therapist and felt empowered to do it with her uncle. The following week she reported that she had used it successfully and, after a few weeks, she felt able to share with her aunt what had been occurring.

Case Example 3

David was a 7 year old child who experienced ongoing severe domestic violence between biological parents. After their separation father began stalking mother. David was very upset about only being able to see his father during twice monthly visits. Whenever he spotted his father, he got very excited and tried to run to see him. Mother was very concerned since the father often became abusive towards her in David’s presence. In one such instance father began shooting a pistol at mother; David ran towards his father as father shot at mother directly over David’s head. Mother was hit with several bullets. After this episode mother sought treatment and TF-CBT began with safety planning. David insisted that his father did not mean to hurt his mother. The therapist met alone with mother. She validated how scary the recent experience had been for mother and that the first priority would be to help David to learn and practice safety strategies in case his father engaged in future violence. Mother was very agreeable to this. The therapist then explained that in order for David to learn safety skills, the therapist, mom and her new partner would need to help David express his positive feelings about his father in safe ways. Mother was initially upset and asked why this was necessary. The therapist explained that her impression was that David kept running to see his father whenever he appeared instead of taking a safer course of action, because he really missed and loved his father, and until he could talk about these feelings, he would not be able to see that sometimes his father was dangerous to be around. Mother thought about this and said that as mad as it made her to realize that David loved her ex, it did make sense to her. The therapist first modeled and then role played several times with mother as the therapist took the part of “David” talking to mother about how great his father was, how much he missed him, how much he wanted to see him, and even complaining to mother about not being able to live together as a family while mother listened supportively. The therapist praised mother repeatedly for being so supportive without getting frustrated. Mother said that she believed she could continue to do this at home. Mother and therapist then discussed a very clear behavioral plan for what David needed to do if father appeared at anytime other than his established bi-weekly visitation schedule. Mother and therapist agreed that the plan was for David to not speak to father and to go to his room or to the car if the family was not at home. They agreed to meet together to discuss safety with David; during this session the therapist would explain the rules to David while mother would express empathy about David missing his father. In this way the neutral therapist could introduce the new safety rules, while mother would maintain the parental role of validating David’s feelings about these rules.

The therapist explained the safety rules and said that David could only see his father at the arranged times. If his father broke the rules and tried to approach the family any other time, David was not to approach father. If David broke the rules, the therapist explained that this would mean that David did not know how to stay safe around father. David became angry, and mother commiserated with him about how hard it was not to be able to live with father. When David blamed mother for this, as the therapist and mother had practiced, mother said, “I know how disappointed you are about this and that it’s really hard for you. If you show me that you can stay safe by following these safety rules, I’ll feel better about you spending time with your father.” David was surprised to hear this from his mother, and he agreed to try to follow the rules. Mother called the therapist later in the week and said that she was pleasantly surprised with David’s response and that he was being much more cooperative with her and her partner.

TF-CBT Strategy #2: Enhancing Parental Engagement

As with any effective trauma treatment model, engagement is a critical part of TF-CBT (Cohen et al, 2006, pp 35–43) since betrayal of trust is a core issue for traumatized individuals that successful therapy must address. Parents who have remained with abusive partners, have repeatedly returned to these partners, or who have gotten into repeated abusive relationships often believe that in these situations, there is more danger in leaving the perpetrator than in remaining. Therapists can successfully engage parents in these situations by simultaneously validating the parent’s desire to protect their children from violence, and the parent’s fear that the perpetrator will become more dangerous if they left. Providing psychoeducation that demonstrates the therapist’s insight into the parent’s present quandary may be a helpful initial engagement strategy. For example, explaining that most battered women leave multiple times before leaving permanently; and validating that the risk of violence often increases at the time the battered woman leaves, often helps mothers trust that their therapist understands the complexity of their situation without seeming judgmental. Engagement is also an important strategy for parents who are inadvertently reinforcing their youth’s negative behaviors due to the parent’s personal trauma issues. This seems to occur in situations in which the youth’s trauma-related behavioral or emotional problems serve as personal trauma reminders for the parent. TF-CBT psychoeducation and other TF-CBT coping skills are unlikely to be useful for these parents and youth unless therapists have first effectively engaged the parent. Working with chronic victims of interpersonal violence can be frustrating for child therapists, who may struggle to feel positively towards parents who seemingly fail to protect their children. In these situations, therapists must remain sensitive to the child’s attachment to and dependence on the non-offending parent, and possibly even the offending caregiver. Such therapists must ask themselves what is best for the child; unless the therapist can maintain effective engagement with the parent, while also taking the appropriate steps to assure youth safety (e.g., making mandated reports to Child Protection), this will ultimately interfere with effective treatment. Some therapists resolve this conflict by not reporting disclosures of child maltreatment, justifying this by telling themselves that doing so will fatally compromise the therapeutic relationship. However, the fact is that youth trusted the therapist to make the disclosure, hoping not only for an empathic response, but also for an end to violence. Therapists who fail to report such abuse not only break the law, they violate the trust that their clients place in them. The following case example illustrates how a therapist maintained engagement while reporting a disclosure of abuse.

Case example

Lori was providing TF-CBT to Naomi and her 6 year old son Peter. During treatment Peter described an episode during which Naomi’s boyfriend Jack beat him with a belt. Peter showed Lori a mark on his leg from the beating. Lori told Peter that as she had said at the start of treatment, she would need to talk to someone whose job it was to keep children safe from abuse, and that she would also talk to mother about this. Peter was worried that mother would get angry at him for “telling on Jack”. Lori reassured Peter that he had done the right thing and met alone with Naomi. Naomi was angry when Lori told her about Peter’s disclosure and accused Lori of “putting ideas into Peter’s head”.

Lori remained very calm and supportive, and validated that this was very upsetting for Naomi to hear. She said, “If someone told me that the person I loved and lived with had hurt my child whom I loved and wanted to protect, it would be impossible for me to believe it too.” Naomi said, “Damn right”. Lori continued, “Being put in the position of having to choose which one to believe would be impossible for me. I wouldn’t know how to do that. So I understand why you are angry at me for telling you this.” Naomi nodded and said, “That’s right. Jack couldn’t have done this. I don’t know why Peter is making this stuff up.” Lori said, “I don’t know the answer to that, but he did show me a belt mark on his leg. Peter told me that Jack hit him with his belt and I know you want to figure out what’s at the bottom of this as much as I do.” Naomi said, “I do want to understand why he would say something like that.” Lori said, “That’s why there are people whose job it is to figure out the truth in these situations. It is just too hard for the people who are so close to the child to sort it out. You or I can call Child Protection and tell them about this and they will help us get to the bottom of it.” Naomi was not happy about calling Child Protection, but agreed to consider it if she could first see the belt mark for herself. When she saw the mark on Peter’s leg, she agreed to call Child Protection with Lori present. While Naomi was still doubtful that Jack had abused Peter, she agreed that someone had hurt her son and wanted to find out how it had happened. Child Protection indicated the report against Jack but Naomi remained engaged with Lori throughout TF-CBT treatment and worked closely with Lori to develop a safety plan. She thanked Lori for “understanding how I felt—not just assuming I was a bad parent from the get-go”.

TF-CBT Strategy #3: Optimally Focusing the Trauma Narration and Processing

Typical goals of the trauma narrative and cognitive processing include: 1) desensitizing youth to feared memories of past traumatic experiences and thus mastering phobic avoidance of these memories; 2) identifying and addressing maladaptive cognitions related to past traumas; 3) contextualizing past trauma into one’s entire life experiences; and 4) preparing the parent to directly support the youth related to past traumatic experiences. Ongoing traumatic experiences provide new opportunities for perpetrators or others to reinforce youth maladaptive cognitions. In our clinical work, we have found that creating narratives are particularly helpful in the following ways for youth experiencing ongoing traumas. First, hearing youths’ detailed trauma experience descriptions results in many non-offending parents more fully acknowledging these experiences, and how they are impacting youths’ behaviors and emotions. Second, describing traumatic experiences from the safety of the therapy session, even if traumatic episodes continue to recur, allows youth to engage in some perspective-taking, cognitive processing and contextualization. Finally, youth gain increased ability to distinguish between real danger and trauma reminders by including descriptions of both types of situations in their narratives. As the narratives unfold parents hear details about what youth have heard and seen, and what they continue to hear and see in the present, that may contrast starkly with their understanding (e.g., “my child has barely seen anything”; “staying together as a family is best for my children”). Hearing their own child speak their personal account has been successful in countering parental minimization about the youth’s experiences, allowing the parent to more appropriately validate the youth’s trauma experiences. This validation is an extremely important step in empowering youth. It is also critical to improving parental protection and, ultimately, supporting parents actualize their best version of themselves as parents. For example, one domestically attacked mother responded to her son’s narrative with new insight: “It was like a light bulb went on in my head. I finally got what it was like …. Until I saw it in his own words, I never got that all this time he’s been living through this just like me.” The following case example illustrates how the trauma narrative enhanced the parent’s support of the youth, addressed the youth’s maladaptive cognitions and helped the youth distinguish between real danger and trauma reminders and hence to implement safety strategies more effectively.

Case example

Jerrrod was a 15 year old who had experienced severe community violence. His mother minimized the degree to which Jerrod’s current school truancy was connected to these traumatic experiences. She was angry that he had been suspended due to frequent truancy and leaving school in the middle of the day. The therapist had tried to develop a safety plan at the start of treatment but mother had minimized the need for this, insisting that their community only had occasional incidences of violence and Jerrod had simply been “unlucky” to witness “a little” violence. The therapist suggested several safety strategies (e.g., having a buddy to walk to school with; developing a safe route to walk to school, etc) but mother minimized the need for these strategies and as a result Jerrod did not use them consistently. During the trauma narrative Jerrod described his worst experience in which he witnessed a young woman being raped and murdered by gang members two blocks from his school. This episode started with the gang members speaking in loud voices to the young woman, then escalated to them pushing her down, repeatedly raping her, then dismembering her body. During this episode Jerrod hid in a dumpster less than 10 feet away, fearing that if he was discovered he would suffer the same fate as the victim. He was afraid to move for more than an hour after the perpetrators left. As he crawled out of the dumpster he was terrified that he would be found and killed. When he got home he was punished for coming home late. Jerrod included in his narrative the statement “If only I had come home early like my parents told me to, this wouldn’t have happened.” As Jerrod provided more details in the narrative, it became clear that both school generally (because the episode occurred close to his school) and loud voices at school (because the episode started with the perpetrators using loud voices and escalated to increasing violence) served as trauma triggers for Jerrod. He often avoided going to school altogether or left school when peers or teachers spoke in loud or harsh voices. This became a focus of differentiating trauma triggers from real danger as described below.

The therapist had previously worked with Jerrod on general cognitive processing using the metaphor of “going from black and white TV to color cable with HD: there are so many more possibilities.” Jerrod agreed that he would much rather have HD cable TV than be restricted to a few black and white channels. In the same way, he agreed that he would rather have a variety of thoughts to choose from when he had an upsetting thought than being stuck with that one thought. The thought, “If only I had come early, this wouldn’t have happened” was an example of an upsetting thought, and Jerrod worked with the therapist to come up with other thought choices from which to choose. One example was, “Even if I hadn’t been there, it still would have happened. I just wouldn’t have seen it.” The therapist said, “Exactly. You being there was terrible for you, but it didn’t change what they did to the young woman. They would have done it whether you were there or not. How does that make you feel?” Jerrod said, “I really wish I wasn’t there, but it still would’ve happened. I just feel bad for the girl who died.” They agreed that this was a much more realistic and helpful thought.

As Jerrod mastered his feared memories about the horrific episode, he was able to more realistically address differences between real danger which was ongoing in his community (e.g., when gangbangers raise their voices they may escalate to violence at any time) versus innocuous trauma reminders (e.g., kids at school argue but these arguments never turn into real violence; teachers use harsh voices and you may get into trouble but this never turns into real violence). The therapist asked Jerrod how he could help himself to recognize the difference between the two, and Jerrod said that he had to remind himself that the latter situations were not really dangerous. The therapist praised him for using this cognitive coping strategy, and suggested that pairing it with a relaxation technique such as grounding, visualization or breathing technique may also help him to “turn down the volume” of the fear he experienced in these situations. He practiced this with the therapist using a loud voice several times in the session, and then said he would try it in school. Mother also supported these strategies at home as described below. Over the next several sessions he returned to school and was able to increasingly tolerate typical peer interactions and stay in school without undue distress.

As Jerrod was developing his narrative, the therapist was sharing it in individual sessions with mother. As mother heard Jerrod’s trauma narrative she was horrified, both that her son had witnessed this level of violence and that she had so grossly underestimated his level of distress. The therapist provided support to mother (“Jerrod didn’t tell you the details before so you had no way of knowing, but now that you do know, there is so much that you can do to help him.”) Mother now understood why school served as trauma reminder and why he avoided school or left school in the middle of the day Mother became much more supportive of Jerrod, and during conjoint sessions mother told Jerrod that she was proud of him for his courage and quick thinking in hiding in the dumpster, and that she now understood why he was skipping school. She apologized to him for minimizing how scared he had been and said that they needed to start on implementing the safety plans the therapist had previously suggested. She was supportive to him as he implemented cognitive coping and relaxation skills and spoke to the school about Jerrod’s treatment plan so that the school could also provide support in this regard as Jerrod attempted to return to school. Although Jerrod continued to witness ongoing community violence, he was able to successfully return to school and use safety skills appropriately without a reemergence of PTSD symptoms.

Summary

Through collaboration with local community organizations, therapists and family members, TF-CBT developers and trainers have developed practical strategies for applying this evidence-based trauma treatment for youth who continue to experience ongoing traumas and their non-offending parents. These strategies include 1) focusing early and as needed on an ongoing basis during therapy on enhancing safety for youth and parent that is appropriate to the youth’s developmental, emotional and situational context; 2) enhancing engagement strategies for parents who are experiencing ongoing personal trauma exposure; and 3) during the trauma narrative and cognitive processing component including focus on enhancing parental acknowledgment and support of the youth’s ongoing trauma experiences; addressing maladaptive cognitions about these experiences; and differentiating between real danger and trauma reminders. Through the use of these strategies, youth exposed to ongoing traumas and their non-offending parents have experienced significant improvement, indicating TF-CBT a viable practical option for working with complex cases where violence risk is not readily or quickly eliminated.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by grants from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Grant No SM 54319) and the National Institute of Mental Health (Grants No R01 MH72590 and K 23 MH 077532). We thank the Women’s Center and Shelter of Greater Pittsburgh, The University of Lusaka and the counselors who participated in these projects. Most importantly we thank the families and children who participated in these projects for their assistance, courage and inspiration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

In order to protect client confidentiality all examples in this paper are composite case descriptions

Contributor Information

Judith A. Cohen, Allegheny General Hospital Department of Psychiatry; Drexel University College of Medicine

Anthony P. Mannarino, Allegheny General Hospital Department of Psychiatry; Drexel University College of Medicine

Laura A. Murray, Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health

References

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Sturge-Apple M, Toth SL. Interaction of child maltreatment and 5-HTT polymorphisms: suicidal ideation among children from low SES backgrounds. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;37:536–546. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Factors that mediate treatment outcome for sexually abused preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1402–1410. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Predictors of treatment outcome in sexually abused children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2000;24:983–994. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Iyengar S. Community treatment for PTSD in children exposed to intimate partner violence: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:16–21. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Perel JM, DeBellis MD, Friedman MJ, Putnam FJ. Treating traumatize children: Clinical implications of the psychobiology of PTSD. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2002;3:91–108. [Google Scholar]

- DeBellis MD, Baum AS, Birmaher B, Keshavan MS, Eccard CH, Boring AM, Jenkins FJ, Ryan ND. Developmenatl traumatology, Part I: Biological stress systems. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:1259–1270. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra S, Irving H, Paglia-Boak A, Wekerle C, Adlaf E, Rehm J. History of family involvement with child protective services as a risk factor for bullying in Ontario schools Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2010;15:157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2009.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Skavenski S, Familiar I, Bass J, Bolton P, Jere E. Catholic Relief Services, SUCCESS Return to Life. Zambia TF-CBT Pilot Project Report to USAID. USAID. 2010

- Murray LK, Haworth A, Semrau K, Singh M, Aldrovandi GM, Sinkala M, Thea DM, Bolton PA. Violence and abuse among HIV-Infected Women and their children in Zambia: A Qualitative Study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006 August;194(8) doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000230662.01953.bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Skavenski S, Jere-Folotiya J, Kasoma M, Dorsey S, Imasiku M, Hupunda G, Bolton PA, Bass J, Cohen JA. An international training and adaptation model: Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children in Zambia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins School of Public Health; 2011. Unpublished manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Skavenski S, Michalopoulos L, Bolton P, Bass J, Cohen JA. Zambian counselor and client perspectives on implementation of TF-CBT. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins School of Public Health; 2011. Unpublished manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Semrau K, Familiar I, Scott N, Johnson E, Thea D, Cohen JA, Bolton P, Haworth A, Imasiku M, Bass J, Chomba E. Demographics of child sexual abuse in Zambia: Data from a one-stop centre. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins School of Public Health; 2011. Unpublished manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]