Abstract

During mitosis, chromatin is condensed into mitotic chromosomes and transcription is inhibited, processes that might be opposed by the chromatin remodeling activity of the SWI/SNF complexes. Brg1 and hBrm, which are components of human SWI/SNF (hSWI/SNF) complexes, were recently shown to be phosphorylated during mitosis. This suggested that phosphorylation might be used as a switch to modulate SWI/SNF activity. Using an epitope-tag strategy, we have purified hSWI/SNF complexes at different stages of the cell cycle, and found that hSWI/SNF was inactive in cells blocked in G2–M. Mitotic hSWI/SNF contained Brg1 but not hBrm, and was phosphorylated on at least two subunits, hSWI3 and Brg1. In vitro, active hSWI/SNF from asynchronous cells can be phosphorylated and inactivated by ERK1, and reactivated by dephosphorylation. hSWI/SNF isolated as cells traversed mitosis regained activity when its subunits were dephosphorylated either in vitro or in vivo. We propose that this transitional inactivation and reactivation of hSWI/SNF is required for formation of a repressed chromatin structure during mitosis and reformation of an active chromatin structure as cells leave mitosis.

Keywords: SWI/SNF complex, nucleosomes, phosphorylation, mitosis, chromatin

Regulation of gene expression occurs in the context of chromatin, whose structure inhibits transcription at different levels including activator binding, preinitiation complex formation, and transcription elongation (for review, see Paranjape et al. 1994; Kingston et al. 1996). The inhibitory effects of chromatin structure on transcription factor function can be alleviated by ATP-dependent remodeling complexes, which include two major classes: complexes that contain the SWI2/SNF2 family of proteins (SWI/SNF and RSC), and ISWI-containing complexes (NURF, ACF, and CHRAC).

All of these remodeling complexes contain a highly conserved subunit that is related to the yeast SWI2/SNF2 protein, which harbors a DNA-dependent ATPase domain (Laurent et al. 1992; Tamkun et al. 1992; Khavari et al. 1993; Muchardt and Yaniv 1993; Chiba et al. 1994). In yeast, the highly related proteins, SWI2/SNF2 and STH1, are part of two distinct remodeling complexes designated SWI/SNF and RSC, respectively (Cairns et al. 1994, 1996; Peterson et al. 1994). In Drosophila, a SWI2/SNF2 homolog termed brahma (Tamkun et al. 1992) is associated with a SNF5-related protein (Snr1) in a large multisubunit complex (Dingwall et al. 1995). A second Drosophila ATPase-containing protein, designated I-SWI (imitation switch), has been shown to be part of at least three different complexes, NURF, ACF, and CHRAC (Tsukiyama and Wu 1995; Ito et al. 1997; Varga-Weisz et al. 1997). In humans, two separate nucleosome remodeling complexes have been isolated that contain the highly related ATPases, Brg1 and hBrm (Kwon et al. 1994; Wang et al. 1996a,b). These complexes are collectively referred to as the human SWI/SNF complexes. The yeast and human SWI2/SNF2-family complexes, and the Drosophila I-SWI-containing complexes have all been purified and shown to alter nucleosome structure in vitro in an ATP-dependent manner (Côté et al. 1994; Kwon et al. 1994; Tsukiyama and Wu 1995; Ito et al. 1997; Varga-Weisz et al. 1997).

Different members of the SWI/SNF family of proteins have been shown to be involved in regulating cell growth and proliferation. Two subunits of the yeast RSC complex, STH1 and SFH1, a SNF5 paralog, are both essential for viability (Laurent et al. 1992; Cao et al. 1997). In contrast, the genes encoding the yeast SWI/SNF complex are not essential for mitotic growth under certain growth conditions (for review, see Winston and Carlson 1992). The role of Brg1 in controlling cell growth in mammals has been elucidated by gene targeting experiments. Inactivation of both alleles of Brg1 in murine F9 cells leads to cell death; however, when a human Brg1 cDNA is stably expressed in these cells prior to the inactivation of both endogenous alleles, cells are able to proliferate (Sumi-Ichinose et al. 1997). This suggests that Brg1 is essential for viability, and further suggests that the function of both RSC and the Brg1-based hSWI/SNF complexes is essential for cell growth and viability (Laurent et al. 1992; Cairns et al. 1996; Cao et al. 1997).

Other studies in human cells have shown that Brg1 and hBrm can interact with the retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressors, and consequently induce cell-cycle arrest (Dunaief et al. 1994; Strober et al. 1996). Moreover, analysis of Brg1 and hBrm during the cell cycle revealed that both proteins undergo phosphorylation on entry into mitosis, and although the level of Brg1 remains constant, hBrm appears to be degraded during mitosis (Muchardt et al. 1996; Reyes et al. 1997). Taken together, these results suggest that some of the components of hSWI/SNF complexes are involved in regulating cell growth, and that their activities are regulated in a cell-cycle dependent manner.

During mitosis, newly replicated interphasic chromatin is condensed into mitotic chromosomes, and many proteins are phosphorylated by specific cyclin-dependent kinases (for review, see Nasmyth 1996; Dynlacht 1997). These changes contribute to the abrupt and general inhibition of transcription during mitosis (for review, see Gottesfeld and Forbes 1997). Mitotic inhibition of gene expression is likely to be caused in part by altering the activity of general transcription factors (Hartl et al. 1993; White et al. 1995; Segil et al. 1996). Other mechanisms for mitotic inhibition of transcription might involve inactivation of gene-specific transcriptional activators (Lüscher and Eisenman 1992), and displacement of these factors from mitotic chromatin (Martinez-Balbás et al. 1995). It might also be important to inactivate remodeling activities during mitosis to allow the tight compaction of DNA. Moreover, a mechanism that reversibly inactivated chromatin remodeling complexes during mitosis could prevent these activities from interfering with the processes that direct chromatin condensation. The cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of Brg1 and hBrm discussed above suggested the possibility that the activity of hSWI/SNF complexes might be regulated in this manner. To address this hypothesis, we developed a cell line that can be used to rapidly purify hSWI/SNF complexes at different stages of the cell cycle. We show here that the hSWI/SNF complexes are reversibly inactivated by phosphorylation as cells traverse mitosis.

Results

Purification of Flag-tagged hSWI/SNF complexes

To purify homogeneous hSWI/SNF complex with high specific activity, we used a helper-free retrovirus system to establish a cell line that expresses an epitope-tagged copy of Ini1, which is the human homolog of yeast SNF5 protein (Kalpana et al. 1994). This strategy has been used previously to immunopurify multisubunit complexes (Zhou et al. 1992). We used the Ini1 gene because attempts to establish cell lines with retrovirally transduced tagged versions of Brg1 or hBrm resulted in cells that grew very slowly (data not shown). In human cells, Ini1 is thus far the only SNF5 homolog found in association with either Brg1- or hBrm-containing hSWI/SNF complexes (Wang et al. 1996a,b). HeLa S3 clones expressing varying levels of carboxy-terminally Flag-tagged Ini1 (FL–Ini1) were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-Flag M2 antiserum that recognizes the Flag–tag epitope (data not shown), and clone FL–Ini1-11 which expresses high levels of FL–Ini1 was selected for further characterization.

Previously, SNF5 has been shown to be a subunit of the yeast SWI/SNF complex, and more recently the yeast SNF5 homolog, SFH1, has been found to be part of the RSC complex (Cairns et al. 1994; Peterson et al. 1994; Cao et al. 1997). To determine whether the tagged Ini1 could interact with endogenous Brg1 and hBrm, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments, and found that FL–Ini1 can form complexes with both Brg1 and hBrm (data not shown, and see below).

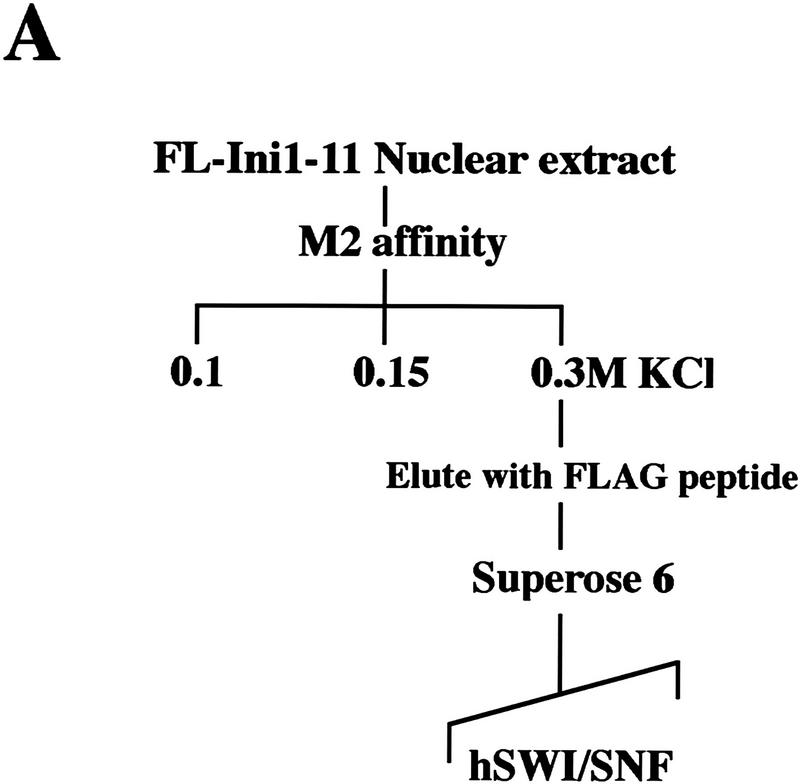

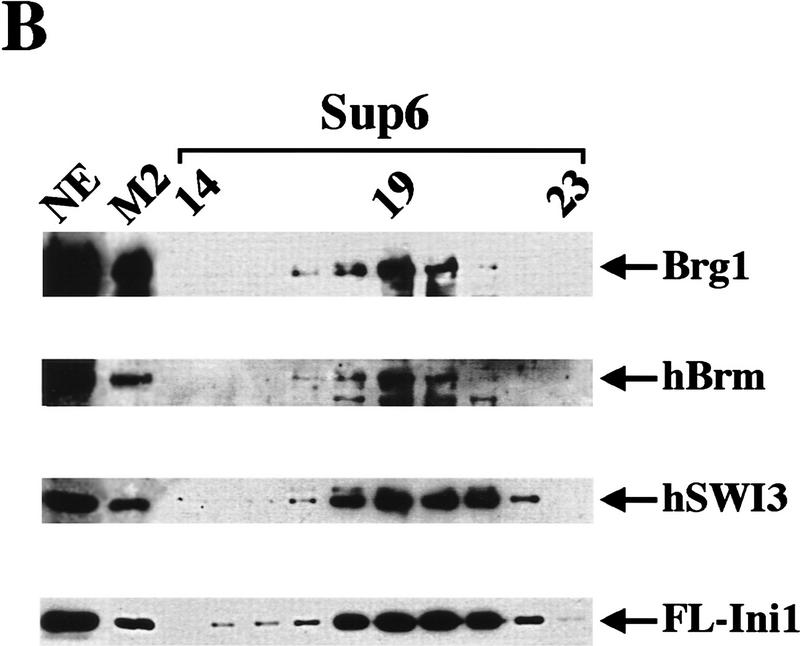

To purify hSWI/SNF complexes, we developed a two-step purification scheme using the FL–Ini1-11 cell line (Fig. 1A). Nuclear extracts were incubated with anti-Flag M2 affinity gel, and after extensive washing with buffers containing increasing salt concentrations, the affinity column was eluted with buffer containing Flag peptide. Using antibodies specific to cloned hSWI/SNF subunits, we were able to detect the presence of Brg1, hBrm, hSWI3, and FL–Ini1 in the eluate (Fig. 1B, lane M2). Analysis of this fraction by SDS-PAGE demonstrated that it contained several prominent bands of the same size as hSWI/SNF subunits (arrows, Fig. 2A, lane 1). The affinity fractionated hSWI/SNF complexes were further purified by gel filtration through a Superose 6 sizing column (Fig. 1A). The Brg1, hBrm, hSWI3, and FL-Ini1 proteins all cofractionated on this column (Fig. 1B). The resultant peak fractions contained nine polypeptides with the characteristic mobility of hSWI/SNF components (arrowheads, Fig. 2A, lane 2). Brg1 and hBrm are believed to form two distinct complexes, each of which contains the other seven indicated subunits (Kwon et al. 1994; Wang et al. 1996a,b). Therefore, we conclude that the FL-Ini1-11 cell line can be used to isolate both the hBrm and the Brg1-based hSWI/SNF complexes.

Figure 1.

Purification of proteins associated with Flag-tagged Ini1. (A) Purification of Flag-tagged hSWI/SNF complexes. FL-Ini1-11 nuclear extracts were incubated with anti-Flag M2 affinity gel, and after several washes with buffer containing increasing amounts of salt, the proteins retained on the affinity column were eluted with buffer containing 20-fold molar excess of Flag peptide. Eluted proteins were then fractionated on a Superose 6 sizing column. (B) hSWI/SNF subunits cofractionate with FL-Ini1. Western blot analysis was performed with 50 μg of nuclear extract (NE); 1.2 μg of affinity purified SWI/SNF fraction (M2), and 15 μl of sizing column fractions 14–23 [Superose 6 (Sup6)].

Figure 2.

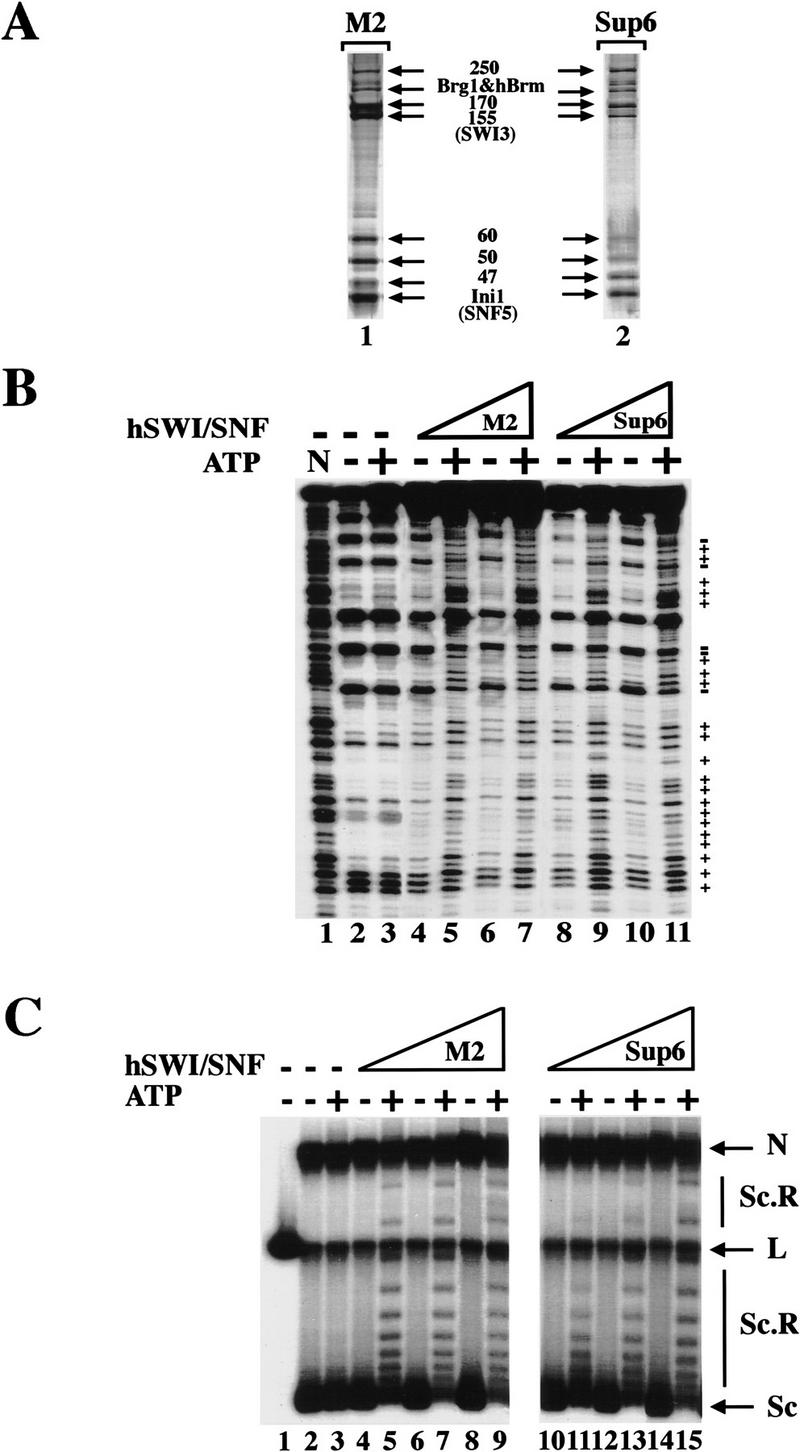

Biochemical characterization of Flag-tagged hSWI/SNF complexes. (A) Amounts of 560 ng of affinity-purified hSWI/SNF (M2, lane 1) and 465 ng of sizing column fraction Superose 6 (sup6), lane 2] were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were visualized by silver staining. (B) Nucleosome disrupting activity. Either 280 ng (lanes 4,5) or 560 ng (lanes 6,7) of M2 fractions was incubated with mononucleosomes with or without ATP. Similarly, 155 ng (lanes 8,9) and 310 ng (lanes 10,11) of Sup6 peak fractions were incubated with core particles as indicated. As a control, naked DNA (N, lane 1) and nucleosomal DNA with or without ATP (lanes 2,3) are shown. Symbols at right indicate the changes to DNase sensitivity caused by hSWI/SNF in an ATP-dependent manner. (C) Remodeling activity on nucleosomal arrays. Increasing amounts of either M2: 19 ng (lanes 4,5), 56 ng (lanes 6,7), 84 ng (lanes 8,9), or Sup6 fractions: 10 ng (lanes 10,11), 31 ng (lanes 12,13), 62 ng (lanes 14,15), were incubated with 8 ng of assembled chromatin templates with or without ATP as indicated. (Lane 1) Linear plasmid DNA (lanes 2,3) assembled template incubated with or without ATP. The resolved DNA templates are supercoiled (Sc); relaxed and supercoiled (Sc.R); linear (L); and nicked (N).

Biochemical characterization of Flag-tagged hSWI/SNF complexes

To determine whether Flag-tagged hSWI/SNF complexes are active, we tested their ability to disrupt nucleosomal core particles (Fig. 2B). When M2 immunoaffinity column fractions were added to the reactions without ATP, there was no significant change in the digestion pattern of nucleosomes (Fig. 2B, lanes 4,6). When ATP was added, disruption of the DNase I pattern was observed (lanes 5,7), and this activity was maximal at a fourfold ratio of hSWI/SNF to nucleosomes (cf. lanes 5 and 7). Similar activity at the same molar ratios was seen with the Superose 6-purified hSWI/SNF (lanes 8–11).

Human SWI/SNF has been shown to efficiently alter the topology of DNA templates that have been assembled into arrays of nucleosomes (Kwon et al. 1994). When the hSWI/SNF fractions tested above were incubated with templates that had been assembled into nucleosomes by use of Drosophila embryo extracts (Bulger and Kadonaga 1994), there was no change in the topology of the plasmid DNA in the absence of ATP (Fig. 2C). However, when ATP was added, the topology of the templates changed, as shown by the decrease in the amount of rapidly migrating DNA and the increase in intermediate species that contain fewer negative supercoils. In this assay, both immunopurified and superose 6 fractions were able to remodel chromatin templates at molar ratios of considerably less than one SWI/SNF complex per nucleosome, showing that these fractions are highly active.

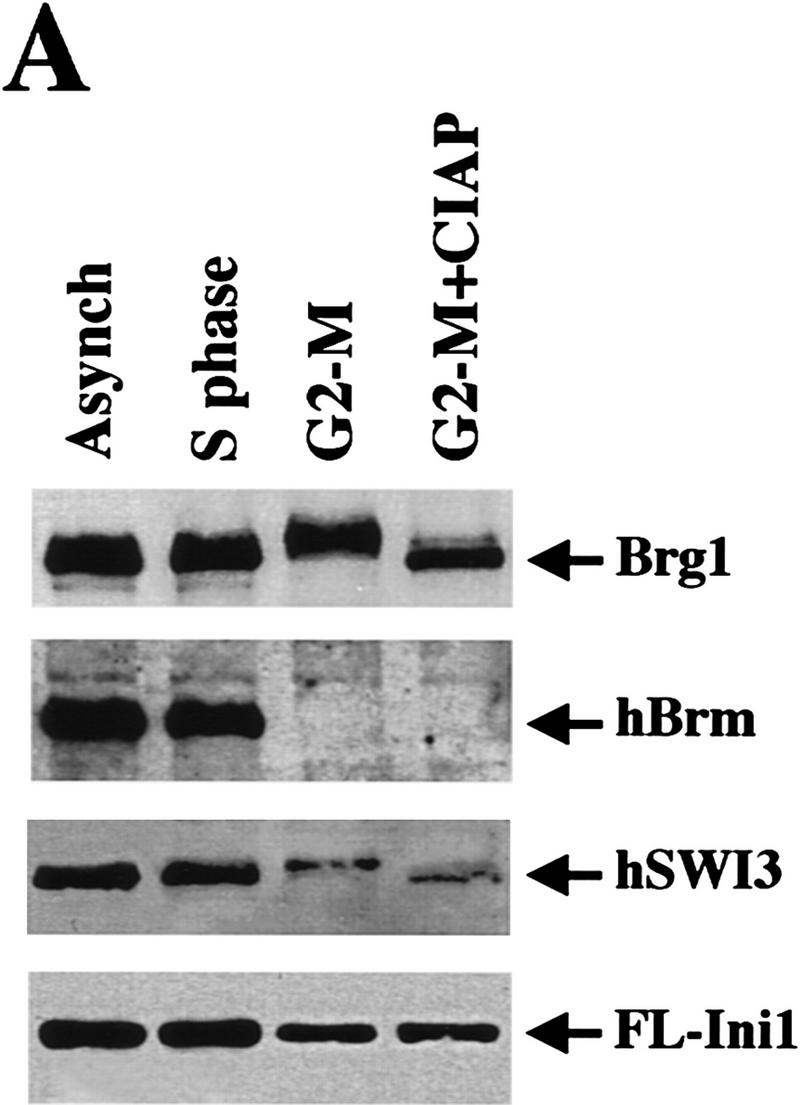

hSWI/SNF nucleosome-disrupting activity is inhibited during mitosis

To examine the subunit composition and nucleosomal disrupting activity of hSWI/SNF complexes during the course of the cell cycle, we used the epitope-tagged Ini1 cell line. Cells were blocked either at S phase (90% of cells were blocked as estimated by flow cytometry) or G2–M phase (94% block) by treatment with hydroxyurea or nocodazole, respectively, and extracts from these cells and from exponentially growing cells (mitotic index <20%) were prepared. Blocking cells at G2–M by nocodazole treatment has been shown to result in phosphorylation of Brg1 and hBrm, and partial degradation of hBrm (Muchardt et al. 1996; Reyes et al. 1997). We reproduced this observation using Western analysis (Fig. 3A). The levels of both proteins remained constant in asynchronous cells and cells blocked at S phase. However, in cells blocked at G2–M, Brg1 migrated with a reduced mobility on SDS–polyacrylamide gels, and hBrm was not detected. Furthermore, when we tested two other subunits, hSWI3 and FL-Ini1, we discovered that hSWI3 also had a slower mobility and the levels of both hSWI3 and Ini1 were slightly reduced in cells blocked at G2-M (Fig. 3A). Treatment of G2–M extract with alkaline phosphatase increased the mobility of both Brg1 and hSWI3, indicating that the change in mobility of Brg1 and hSWI3 was caused by phosphorylation of these proteins in the G2-M extracts.

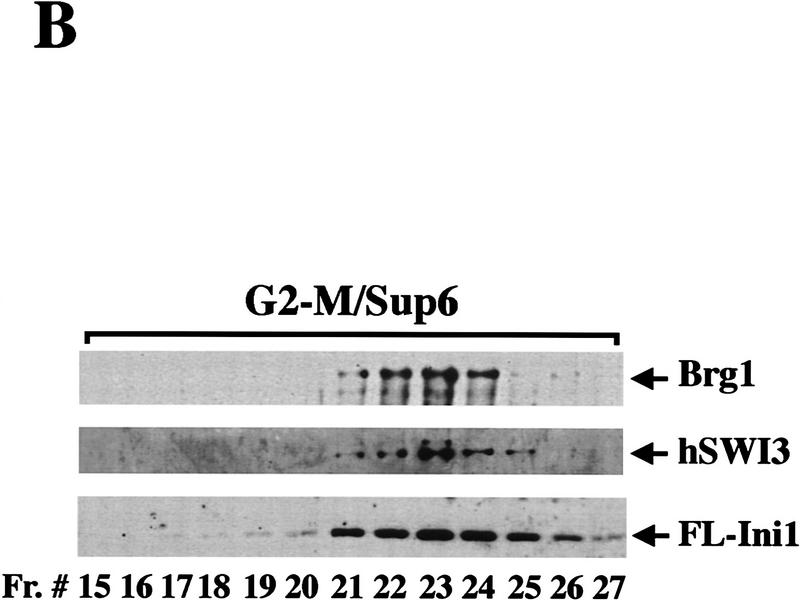

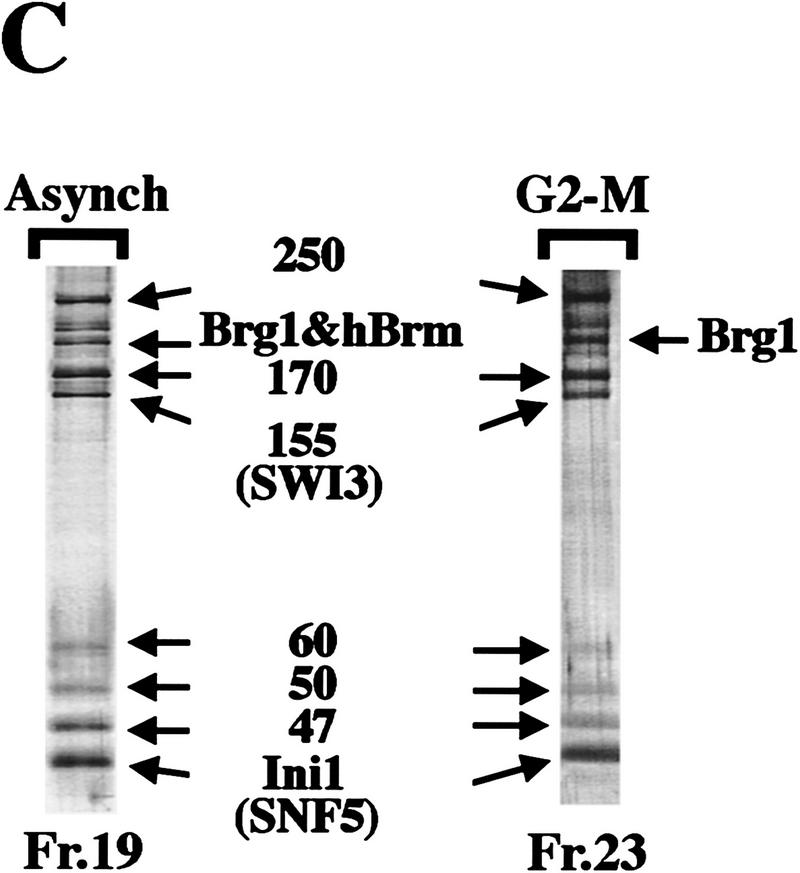

Figure 3.

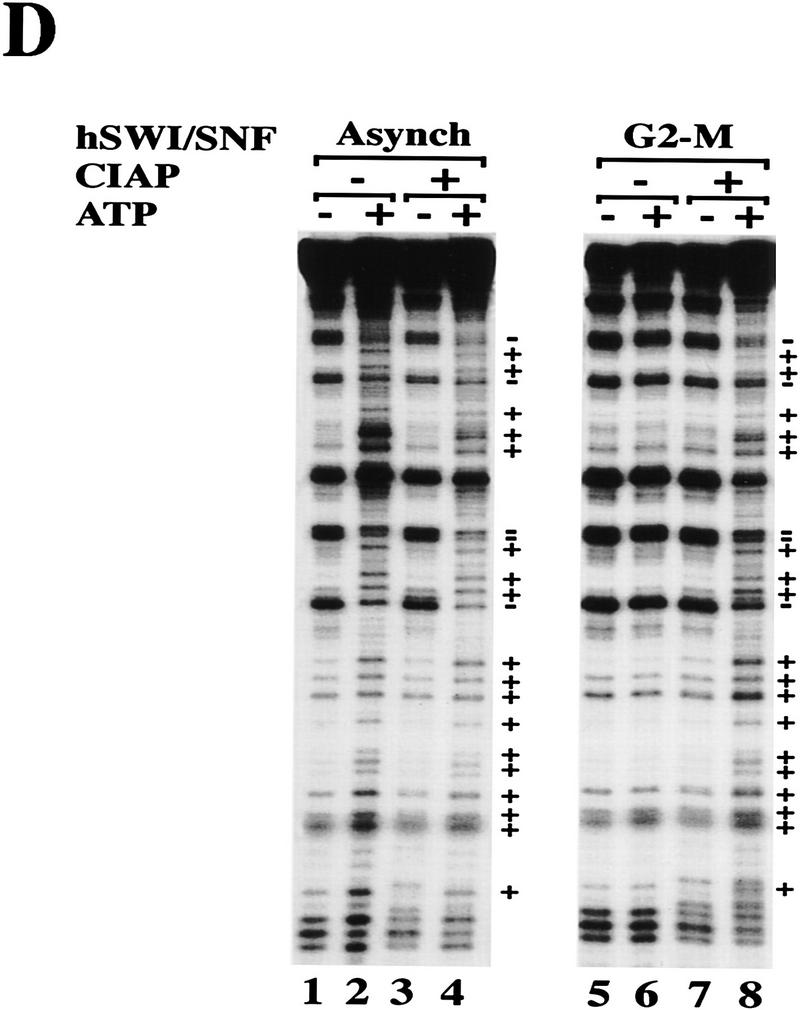

Mitotic hSWI/SNF is phosphorylated and lacks nucleosome disrupting activity. (A) hSWI/SNF subunits are regulated differently during mitosis. Approximately 10 μg of total protein from exponentially growing cells (Asynch), cells blocked in S phase (S phase), or cells blocked in prometaphase (G2–M) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Brg1, anti-hBrm, anti-hSWI3, or anti-Flag antiserum. Where indicated, proteins were incubated with 10–20 units of calf alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) for 45 min at 37°C. (B) Mitotic hSWI/SNF subunits cofractionate through Superose 6 (Sup6) sizing column. Western blot analysis of Sup6 column fractions (fr.) 15–27, with anti-Brg1, anti-hSWI3, and anti-Flag antisera. Mitotic hSWI/SNF subunits consistently (n = 4) eluted later (fr. 23) than the asynchronous complex (fr. 19). (C) Mitotic hSWI/SNF complex is intact. Equal amounts of hSWI/SNF sizing column peak fractions (∼500 ng) from either exponentially growing cells (Asynch, fr. 19), or cells blocked in early mitosis (G2–M, fr. 23) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. (D) Phosphatase treatment of mitotic hSWI/SNF enables the complex to disrupt mononucleosomes. Similar amounts of Sup6 fractions from either asynchronous cells (500 ng) or cells blocked in G2-M (560 ng) were incubated with mononucleosomes with or without ATP and CIAP as indicated.

We examined the integrity of the hSWI/SNF complexes isolated at various stages of the cell cycle by using immunoaffinity fractionation on an anti-Flag M2 column. Analysis by silver staining of the proteins purified from asynchronous, S-phase or G2-M extracts showed that their polypeptide composition was grossly similar, suggesting that hSWI/SNF complexes remained intact at different stages of the cell cycle (data not shown and see below). Activity of these fractions was tested by use of mononucleosome disruption assays (data not shown and see below). hSWI/SNF complexes from either asynchronous cells or cells blocked at S phase were able to disrupt nucleosomal core particles to the same extent in an ATP-dependent manner. However, when hSWI/SNF complex purified from cells arrested at G2–M was used in this assay, DNase I activity was inhibited, and no significant ATP-dependent effects were observed.

We further purified hSWI/SNF from the G2–M phase using a Superose 6 sizing colum (Fig. 3B), and compared it with hSWI/SNF purified in the same manner from asynchronous cells. The activity in the G2–M preparation that inhibits DNase I eluted at a larger apparent size (fr. 19) than the hSWI/SNF subunits on this column (data not shown), and therefore was not pursued further in this work. The hSWI/SNF complex purified from G2–M had a composition similar to that of the complex purified from asynchronous cells (Fig. 3B,C), and eluted at a smaller apparent native molecular weight than the asynchronous complex on an equivalent Superose 6 column (mitotic hSWI/SNF subunits peak at fr. 23, Fig. 3B and asynchronous hSWI/SNF peaks at fr. 19, Fig. 1B). However, unlike hSWI/SNF purified from asynchronous cells, mitotic hSWI/SNF lacks nucleosome remodeling activity in the presence of ATP (Fig. 3D, cf. lane 6 with lane 2). When both asynchronous and mitotic hSWI/SNF fractions were treated with alkaline phosphatase, however, they were both able to alter nucleosome structure in the presence of ATP (Fig. 3D, cf. lanes 4 and 8 with lane 2). Taken together, these findings show that phosphorylated hSWI/SNF isolated from cells at G2–M is inactive, and that dephosphorylation restores its nucleosome remodeling activity.

hSWI/SNF complex is reactivated as cells exit mitosis

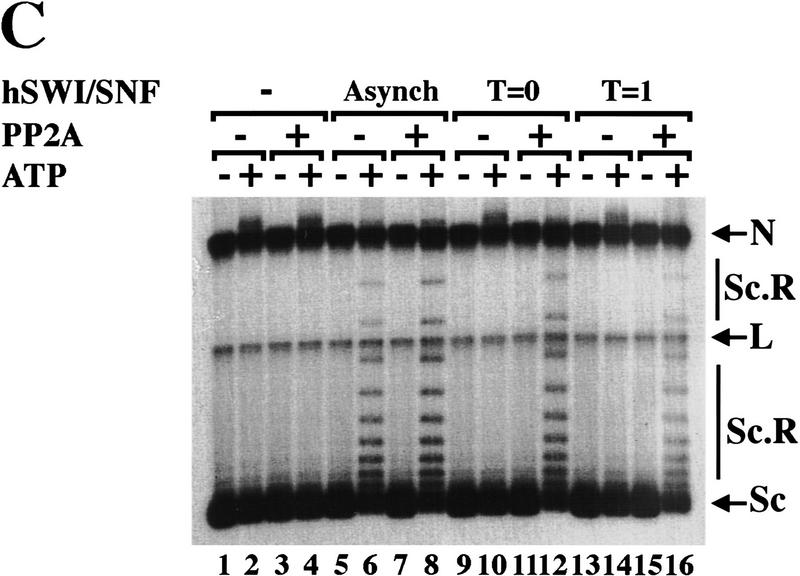

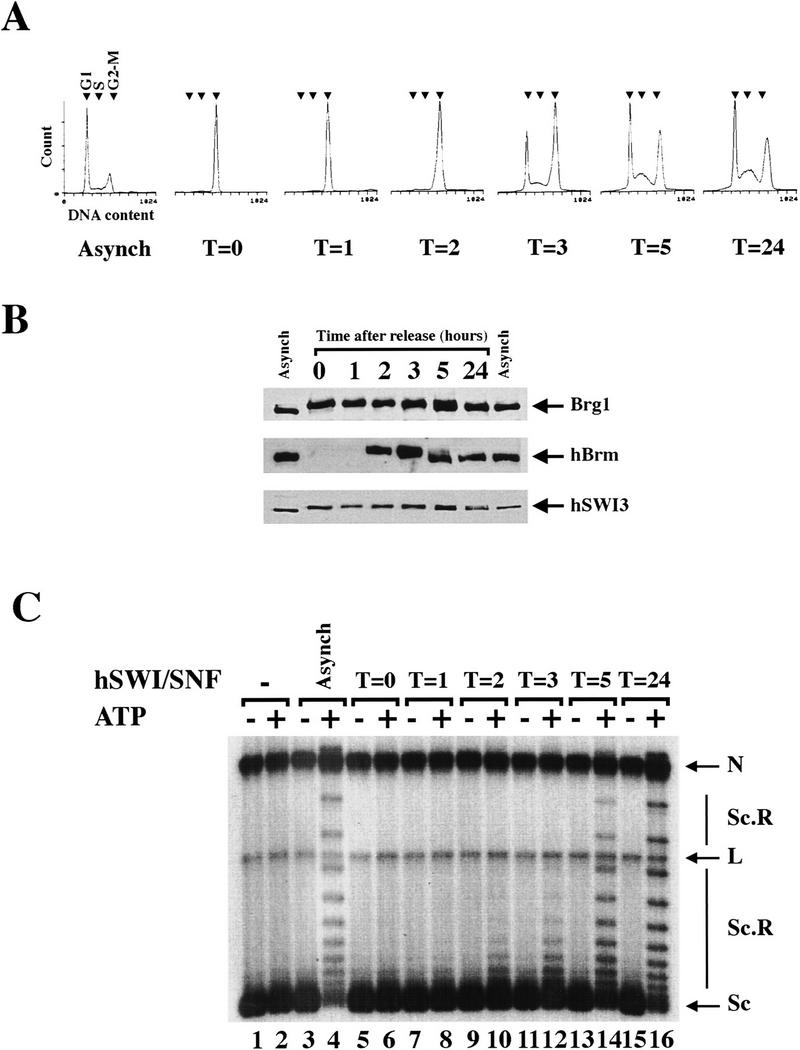

To examine when hSWI/SNF regained activity, we carried out a detailed analysis of its activity as cells exit mitosis. Cell were synchronized with nocodazole in G2–M, and then were released by washing in medium without drug. After release from the G2–M block, cells were collected at different times, and hSWI/SNF was immunoaffinity purified and its activity was measured by determining the effect on the supercoiling of assembled plasmid templates. In parallel, the DNA content of each sample was determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 4A). Most cells traversed mitosis within 2–3 hr, and after 3 hr cells started to enter G1. Analysis of the DNA content of cells released from the G2–M block revealed that by 5 hr after release, cells began to show a profile that was similar to that of exponentially growing cells.

Figure 4.

Cell cycle-dependent reactivation of hSWI/SNF complexes. (A) Exponentially growing FL-Ini1 cells were synchronized in G2–M by nocodazole treatment, and then released from the block by washing in medium without drug. Cells were harvested at the indicated times (T), and their DNA content was determined by FACS analysis. For comparison, the DNA content of exponentially growing cells (Asynch) is shown. Small arrowheads indicate the position of each stage of the cell cycle. (B) Cell cycle-dependent dephosphorylation of hSWI/SNF subunits. hSWI/SNF complexes were affinity purified from either asynchronous cells (Asynch), or cells blocked in G2–M and then released (T = 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 24), and hSWI/SNF fractions were then examined for their protein composition and phosphorylation state. Approximately 200 ng of each fraction was analyzed by Western blotting with either anti-Brg1, anti-hBrm, or anti-hSWI3. (C) hSWI/SNF reactivation correlates with dephosphorylation of its subunits. Equal amounts (200 ng) of affinity-purified hSWI/SNF fractions from asynchronous cells (lanes 3,4), cells blocked in G2–M (lanes 5,6), or cells that were released from the block (lanes 7–16) were tested for chromatin remodeling activity by use of an 8 ng assembled template, with or without ATP as indicated. Nicked closed circular (N); linear (L); supercoiled (Sc); and supercoiled and relaxed (Sc.R) plasmid DNA are indicated.

We also examined the protein levels and phosphorylation state of Brg1, hBrm, and hSWI3 for each sample (Fig. 4B), and found that both Brg1 and hSWI3 were still phosphorylated 2–3 hr after release from the block. Both proteins appeared to undergo dephosphorylation ∼3–5 hr after release, and became completely dephosphorylated by 24 hr. hBrm was not detected in the affinity-purified hSWI/SNF fractions until 2 hr after release, at which time it was present and migrated more slowly, consistent with a phosphorylated state (Fig. 4B). The kinetics of dephosphorylation of hBrm correlated with those of Brg1 and hSWI3.

When we tested hSWI/SNF fractions purified from cells blocked in G2–M, and cells that were released from nocodazole block for activity (Fig. 4C), we found that the complex began to regain chromatin remodeling activity 2–3 hr after release, and was more active by 5 hr. The activity of hSWI/SNF at 5 and 24 hr after release was comparable with that of the purified complex from asynchronous cells. Moreover, the ability of the hSWI/SNF complex to remodel chromatin correlated with dephosphorylation of Brg1, hBrm, and hSWI3. These data show that hSWI/SNF is reactivated as cells leave mitosis and enter interphase, and that blocking FL-Ini1 cells with nocodazole did not result in an irreversible modification of hSWI/SNF complexes.

hSWI/SNF complex is inactivated in vitro by ERK1 and reactivated by protein phosphatase 2A

To test whether phosphorylation is the only modification required to inactivate the hSWI/SNF complex, we sought to identify a kinase that can phosphorylate hSWI/SNF and alter its activity. Previously, it has been shown that Brg1 is phosphorylated in unfertilized Xenopus eggs, which are naturally blocked in metaphase (Stukenberg et al. 1997). Fractionation of Xenopus egg extracts revealed that a single peak of activity that can phosphorylate Brg1 perfectly cofractionates with ERK1 (T. Stukenberg, unpubl.).

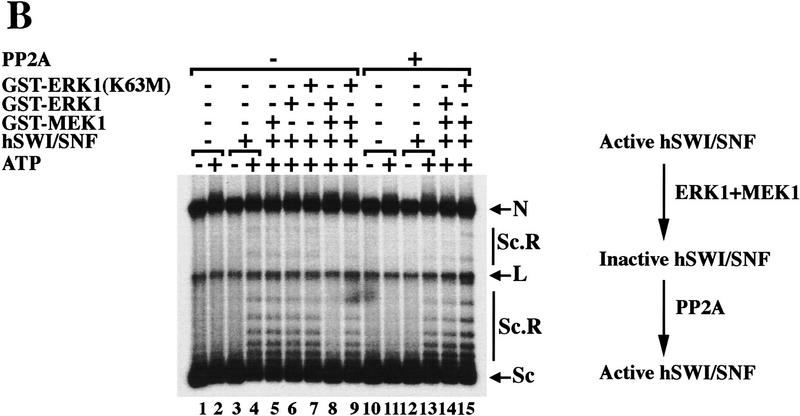

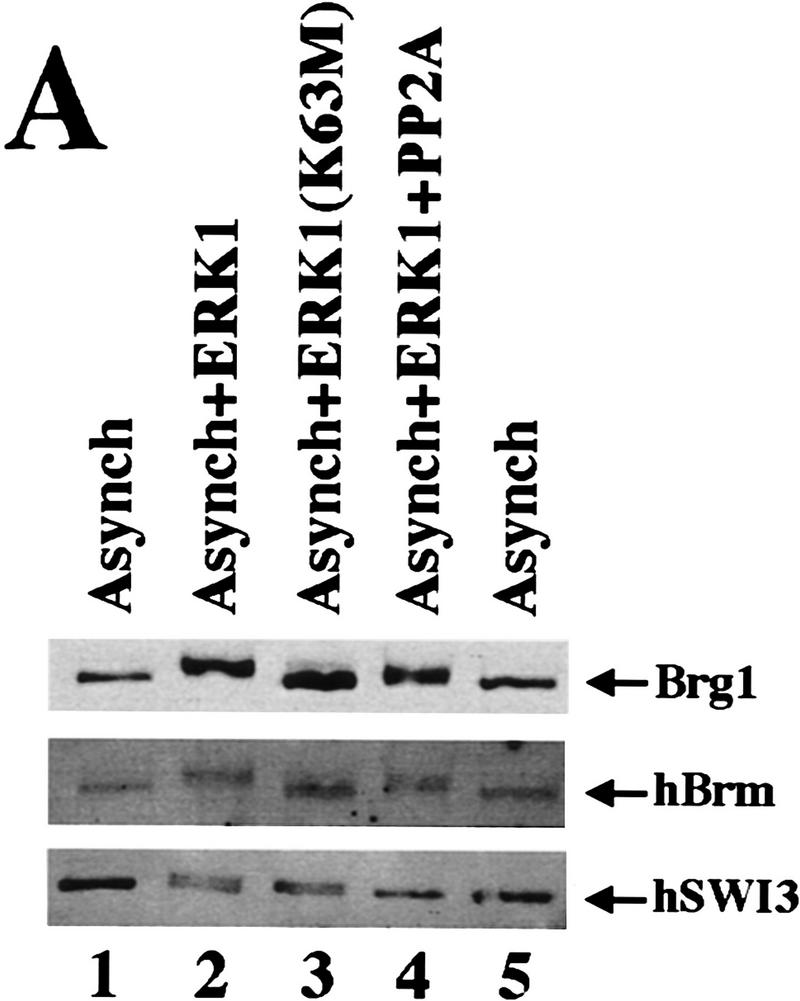

To determine whether ERK1 can phosphorylate human SWI/SNF subunits, we tested MEK1-activated ERK1 for its ability to phosphorylate the hSWI/SNF complex. We found that wild-type GST–ERK1 can phosphorylate SWI/SNF subunits, whereas a kinase-deficient form of GST–ERK1 cannot (Fig. 5A, lanes 2,3). Furthermore, other well-characterized mitotic kinases such as cdc2-cyclinA, cdc2–cyclinB and polo-like kinase 1, were unable to phosphorylate SWI/SNF subunits (data not shown). When we tested the hSWI/SNF complex that is phosphorylated in vitro by activated GST–ERK1 for its ability to remodel chromatin templates, we found that it was inactive (Fig. 5B, lane 8); however, when mutant GST–ERK1 (K63M) that lacks kinase activity was used, hSWI/SNF was still able to remodel assembled templates in an ATP-dependent manner (Fig. 5B, lane 9). In addition, inhibition of hSWI/SNF activity depended on the presence of wild-type GST–ERK1 that is activated by GST–MEK1, and not GST–MEK1, GST–ERK1, or GST–ERK1 (K63M) alone (Fig. 5B, lanes 5–7).

Figure 5.

Active hSWI/SNF is inhibited by ERK1 in vitro. (A) Brg1, hBrm, and hSWI3 are phosphorylated in vitro by GST–ERK1. Equal amounts (0.75 μg/15 μl reaction) of either wild-type GST–ERK1 or mutant GST–ERK1 (K63M) were activated by GST–His–MEK1 (0.25 μg/15 μl reaction) as described in Materials and Methods. Approximately 200 ng of asynchronous SWI/SNF was added to the reactions containing either GST–ERK1 (lane 2), or GST–ERK1 (K63M) (lane 3). Samples were incubated at 30°C for 1 hr and analyzed by Western blotting. When PP2A was added (lane 4), the GST fusion proteins were removed by adding GST beads to the reactions, and the supernatant was incubated with 0.1 units of PP2A at 30°C for 1 hr. As a control, asynchronous hSWI/SNF subunits are shown (lanes 1,5). (B) hSWI/SNF that is phosphorylated in vitro by ERK1 is inactive. Asynchronous hSWI/SNF fractions were incubated (conditions as in A) with either MEK1-activated or inactive GST–ERK1 and GST–ERK1 (K63M) as indicated. As controls, hSWI/SNF was also tested for activity after incubation with either GST–MEK1 (lane 5), GST–ERK1 (lane 6), or GST–ERK1 (K63M) (lane 7). When PP2A was added (lanes 10–15), samples were treated as described in A. Assays are performed as in Fig. 4. (C) Brg1-containing complex is efficiently reactivated by PP2A. hSWI/SNF fractions purified from cells growing exponentially (Asynch), cells blocked in G2–M (T = 0), or cells blocked and then released (T = 1), were incubated with supercoiled templates with or without ATP and PP2A as indicated. When PP2A was added, samples were preincubated with 0.1 units of PP2A at 30°C for 1 hr.

Because ERK1 is serine/threonine protein kinase, we wanted to determine whether we could reactivate hSWI/SNF efficiently by using a phosphatase that is specific for phosphoserine and phosphothreonine, such as protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A). Active hSWI/SNF was incubated with or without GST–ERK1 and GST–ERK1 (K63M), and the GST fusion proteins were then removed by adding glutathione beads to the reactions. The supernatant that contained phosphorylated and inactive hSWI/SNF, was incubated with PP2A, and then either analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 5A) or tested for activity (Fig. 5B).

Treatment of phosphorylated SWI/SNF with PP2A caused partial dephosphorylation of Brg1 and hBrm, and complete dephosphorylation of hSWI3 (Fig. 5A, lane 4). Treatment with PP2A reactivated phosphorylated SWI/SNF (Fig. 5B, cf. lane 14 with lane 8), essentially back to starting levels (Fig. 5B, cf. lane 14 with lane 13). These data show that hSWI/SNF activity can be turned off in vitro with ERK1 and turned on with PP2A, and therefore show a strong correlation between SWI/SNF activity and phosphorylation state.

Mitotic and inactive Brg1-containing complex is reactivated by PP2A

SWI/SNF activity is regained when Brg1 and hSWI3 become dephosphorylated either in vitro by alkaline phosphatase or in vivo as cells exit mitosis (Figs. 3,4). To determine whether the Brg1-containing complex can be reactivated by PP2A, we examined hSWI/SNF fractions that contain Brg1 but not hBrm (Fig. 4B, T = 0 and T = 1). Following PP2A treatment, both fractions were able to efficiently remodel chromatin templates (Fig. 5C, cf. lanes 12 and 16 with lanes 10 and 14), suggesting that the Brg1-based complex isolated from cells in mitosis can be fully reactivated by dephosphorylation by PP2A.

Discussion

We have developed a cell line that can be used to rapidly purify hSWI/SNF complexes to near homogeneity through a two-step purification method. When we examined the activity of hSWI/SNF complexes at different stages of the cell cycle, we found that hSWI/SNF purified from cells blocked in prometaphase is inactive, contains Brg1 but not hBrm, and is phosphorylated on Brg1 and hSWI3. When this complex was treated in vitro with phosphatase, it regained ATP-dependent remodeling activity. We have also shown that active hSWI/SNF from asynchronous cells can be phosphorylated and inhibited in vitro by ERK1, and that phosphatase treatment of this complex results in its efficient reactivation. These data suggest that hSWI/SNF activity is regulated by phosphorylation as cells traverse mitosis.

Inactivation of hSWI/SNF activity occurs as cells enter mitosis and chromosomes become condensed and many genes become transcriptionally inactive. The nucleosome remodeling activity of SWI/SNF is believed to play a direct role in activating gene expression by increasing transcription factor access to chromatin, and thus inactivation of this complex might be one mechanism of inhibiting gene expression during mitosis. It is also possible that inactivation of this complex is an important step in the process that leads to efficient condensation of chromatin structure. The Brg1-based hSWI/SNF complex is present at high levels, and the remodeled chromatin state that results from its action might not be a suitable substrate for the proteins that condense chromatin. The observed reversible inactivation of the intact Brg1-based complex is a parsimonious solution to the problem of inactivating remodeling complexes when chromosomes become condensed and inactive. By keeping this complex intact during mitosis, it is possible that it can be rapidly reactivated when cells exit mitosis and require an active nucleosome remodeling activity to reactive gene expression.

Brg1 and hBrm-based hSWI/SNF complexes are regulated differently during mitosis

It is not clear what mechanisms are used in the cell to distinguish the Brg1-based complex from the hBrm-based complex. Both complexes appear to have very similar if not identical subunit composition, with the only clear difference being the nature of the ATPase associated with the complex. It is clear, however, from both this work and previous work (Muchardt et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996b) that the two complexes play different roles and are regulated differently in vivo. We have shown that the Brg1-based complex is soluble and intact in cells blocked in G2–M, and contains all of the subunits characteristic of hSWI/SNF complexes (Fig. 3C). The majority of Brg1 protein becomes dephosphorylated 5 hr after cells are released from a nocodazole bock (Fig. 4B; Muchardt et al. 1996). Reactivation of hSWI/SNF activity occurs with the same kinetics as dephosphorylation of the Brg1 and hSWI3 proteins in vivo. The reactivation of hSWI/SNF activity is likely to be caused in large part by reactivation of the Brg1-containing complex, as dephosphorylation of fractions that contain only phosphorylated Brg1, and not hBrm, leads to reactivation of ATP-dependent remodeling (Fig. 5C).

The inactivation of the hBrm-based complex, which appears to be targeted for degradation during mitosis, is another mechanism by which cells might inhibit nucleosome remodeling complexes. Western analysis on whole cells shows that most of the hBrm is degraded in cells blocked in G2–M, but there remains a small amount that is not soluble (data not shown). The level of hBrm is restored to normal 2 hr after release from the block, and it is at this time that it becomes detectable in the affinity-purified fractions. The levels of hSWI3 and Ini1, both of which are components of hBrm complexes, are also reduced slightly during mitosis and increase 2 hr after release from nocodazole block. It appears, therefore, that the hBrm-based complex is targeted for degradation during mitosis.

Regulation of hSWI/SNF activity by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation

It is not known which kinase(s) are responsible for phosphorylation of hSWI/SNF subunits as cells enter mitosis, and which phosphatase(s) are required for dephosphorylation later in the cell cycle. Cdc2 is considered to be essential for G2-to-M transition and appears to phosphorylate a wide variety of proteins (Riabowol et al. 1989). Previous work with the Xenopus homolog of human Brg1 showed that Xenopus Brg1 is phosphorylated during mitosis; however, it is not phosphorylated by cdc2-cyclinB kinase in vitro (Stukenberg et al. 1997). This is in accord with our findings that mitotic kinases such as cdc2–cyclinA, cdc2-cyclinB, and polo-like kinase 1 do not phosphorylate hSWI/SNF subunits.

We have found that active ERK1 can phosphorylate and thus inactivates hSWI/SNF complexes. The involvement of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal transduction pathway in mitosis is not well understood; however, recently MEK1 has been shown to be involved in the golgi fragmentation that occurs during mitosis by activating a novel ERK that is associated with the golgi membrane (Acharya et al. 1998). We have shown that ERK1 can inhibit hSWI/SNF activity by phosphorylating Brg1, hBrm, and hSWI3 in vitro, and that these same SWI/SNF subunits are also phosphorylated in vivo. There are thirteen potential MAPK sites in Brg1, and seven in hSWI3, so it is not clear at this time what portion of these large proteins might be phosphorylated. It is possible that ERK1, or another MAPK with similar substrate specificity, might be involved in regulating hSWI/SNF activity during mitosis; however, it is also possible that other kinases are involved. Further experiments are needed to clarify the role of the MAPK family of proteins in regulating the activity of chromatin remodeling complexes in vivo.

Regulation of hSWI/SNF complexes by phosphorylation leads to their exclusion from condensed chromatin (Muchardt et al. 1996) and to the inactivation of Brg1-containing complexes and degradation of hBrm-based complexes. We do not yet understand the mechanism by which phosphorylation inactivates the Brg1 complex. The phosphorylated Brg1 complex, which contains all of the SWI/SNF subunits, elutes at a smaller apparent native molecular weight than the nonphosphorylated complex on a sizing column (Fig. 3; data not shown). It is possible that phosphorylation causes a conformational change that alters the mobility of the complex, or that there is a monomer–dimer transition of the complex. The FL-Ini1 cell line that we have developed can be used to further define how the characteristics of SWI/SNF change with and without phosphorylation, and how SWI/SNF activity changes as cells traverse the cell cycle.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructions

Plasmic pBabe/FL-Ini1 for the expression of carboxy-terminally Flag-tagged Ini1 was generated by subcloning the 1.2-kb fragment described below into the unique EcoRI site of the retroviral vector pBabe (Morgenstern and Land 1990). Ini1 cDNA sequences were obtained by PCR amplification from a human peripheral blood cDNA library (HPB-ALL) by use of two oligonucleotides (5′-CCGGAATTCCCGCCTCTGCCGCCGCAATG-3′, and 5′-CGGAATTCCTCATTATTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTCCCAGGCCGGGCCCGTGTTGGCAAGACG-3′, Ini1 sequences are shown in boldface type) containing EcoRI sites, which are specific for the Ini1 cDNA (nucleotides 52–72 and 1198–1224, respectively, Kalpana et al. 1994). The 3′ primer was designed to incorporate a Flag-tagged (DYKDDDDK) sequence before the stop codon of Ini1. To generate plasmid pGEX–5cSWI3 for the expression of GST–hSWI3 (amino acids 672–771) fusion protein, a partial human SWI3 (hSWI3) cDNA encoding amino acids 1–808 was isolated by screening the HPB–ALL plasmid library with a 0.68-kb human cDNA probe, which encodes amino acids 424–563 (kindly provided by Alexander Strunnikov and Doug Koshland, Carnegie Institution of Washington). Several clones were isolated and the longest hSWI3 cDNA (2.5 kb) was sequenced and found to be similar but not identical to hSWI3 (BAF155) (Wang et al. 1996a). Using this partial hSWI3 cDNA clone, a 0.36-kb fragment encoding amino acids 672–771 was generated with specific primers, which introduced a BamHI and an EcoRI site at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The BamHI–EcoRI fragment was subcloned into pGEX–2TK (Pharmacia, Inc.) to generate pGEX–5cSWI3.

Establishment of cell lines expressing FL-Ini1

Retroviral expression plasmid pBabe/FL-Ini1, which contains a puromycin resistance gene, was transfected into the Bing-packaging cell line essentially as described previously (Ausubel et al. 1996). Briefly, 20 μg of plasmid DNA was used to transfect 2 × 106 Bing cells by the calcium phosphate method in the presence of 25 μm/ml chloroquine. Medium containing helper-free and replication-deficient retrovirus was harvested 48–72 hr posttransfection, and used to infect 2 × 106 freshly seeded HeLA S3 cells in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene. Infected cells were grown in medium containing 2 μg/ml puromycin, and individual colonies were isolated and expanded into cell lines. Four clones that were estimated to express varying levels of FL-Ini1 were expanded into large volumes of medium containing puromycin at Cellex Biosciences, Inc.

Purification of Flag-tagged hSWI/SNF complexes

Clone FL-Ini1-11 was used to prepare nuclear extracts as described previously (Dignam et al. 1983; Li et al. 1991). Approximately 60 mg of nuclear proteins were incubated with 1 ml of anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Kodak, Inc.) at 4°C for 8–12 hr. Beads were then loaded onto a column and washed extensively with buffer BC-0 [20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 20% glycerol, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT and 0.5 mm PMSF] supplemented with 0.15 m KCl, followed with a wash with buffer BC-0.3 (BC-0 containing 300 mm KCl). Bound proteins were eluted in BC-0 containing 100 mm KCl (BC-0.1) and a 20-fold molar excess of Flag peptide (Kodak). The concentration of immunopurified hSWI/SNF complexes was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), and proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining as described previously (Kwon et al. 1994). Affinity-purified complexes were then fractionated on a Superose 6 sizing column (Pharmacia). All Superose 6 columns were 40 ml, were equilibrated in buffer BC-0.1, and 1-ml fractions were collected.

Cell culture synchronization

FL-Ini1 cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle media (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) until they reached 30%–40% confluence, then they were fed with medium containing either 10 mm hydroxyurea for 24 hr (S-phase block), or 330 nm nocodazole for 20–24 hr (G2–M block). Cells were then collected, washed twice with PBS, and extracts were prepared as described previously (Dignam et al. 1983; Li et al. 1991). When cells were released from the nocodazole block, they were washed with PBS, resuspended in medium without nocodazole and grown at 37°C before they were harvested at different times. The DNA content of each sample was determined as described previously (Ausubel et al. 1996).

Nucleosome disruption assays

A DNA fragment of ∼150 bp, which contains two copies of a 20-bp artificial nucleosome positioning sequence at one end and a TATA box in the middle, was obtained by digesting plasmid TPT with EcoRI and MluI (plasmid pTPT, Anthony Imbalzano, unpubl.). The EcoRI–MluI fragment was 32P-labeled and was assembled into a mononucleosomal core particle in the presence of purified HeLa core histones by salt dilution as described (Imbalzano et al. 1994). Assembled templates were purified by glycerol gradient sedimentation and 3.3 ng of nucleosome core particles was incubated with or without ATP and hSWI/SNF fractions in a 25 μl reaction containing 12 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 60 mm KCl, 6 mm MgCl2, 60 μm EDTA, 2 mm DTT and 13% glycerol. Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 30 min, treated with DNase I (0.2 units) for 2 min at room temperature, and analyzed on an 8% SDS–polyacrylamide-denaturing gel.

Chromatin remodeling assays

A 2.7-kb plasmid DNA was linearized with EcoRI, treated with alkaline phosphatase, and kinased with T4 polynucleotide kinase. The labeled plasmid DNA was religated and used to reconstitute chromatin templates as described previously (Becker and Wu 1992; Bulger and Kadonaga 1994). Briefly, 1 μg of internally labeled plasmid DNA was incubated with 1.5 mg of S-190 Drosophila embryo extract (Bulger and Kadonaga 1994) and 0.6 μg of HeLa core histones at 27°C for 5 hr. Reactions were stopped with 0.5 m EDTA to a final concentration of 20 mm. Assembled chromatin templates were purified by glycerol gradient sedimentation, and incubated for 60–90 min at 30°C with or without ATP and hSWI/SNF fractions in a 25 μl reaction supplemented with wheat germ topoisomerase I (Promega) as described for nucleosome disruption assays. Reactions were then stopped with buffer B [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.1 mm EDTA, 25% (vol/vol) glycerol, 3% (wt/vol) SDS, 0.04% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue and 0.04% (wt/vol) xylene cyanol] supplemented with 2 mg/ml proteinase K, then were incubated at 37°C for 30–40 min before they were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel.

Kinase assays

Wild-type and mutant GST–ERK1, and their activating kinase, GST–His–MEK1, were prepared as described (Crews et al. 1991, 1992; Huang and Erikson 1994). Both GST–ERK1 and GST–ERK1 (K63M) were activated by a constitutively active form of MEK1 in a 15 μl reaction containing kinase buffer [15 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 15 mm MgCl2, 75 μg/ml BSA, 1 mm ATP] at 30°C for 1 hr. Active hSWI/SNF was added to the reactions, and ATP was added to a final concentration of 2 mm. Samples were incubated at 30°C for 1 hr, and were either added directly to the reactions containing supercoiled templates as described above, or analyzed by Western blotting. When samples were dephosphorylated, GST fusion proteins were removed by adding GST beads that were pre-equilibrated in buffer BC-0.1 to the reactions. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and protein phosphatase 2A (CAL Biochem, Inc.) (final concentration of 0.1 units) was added to the supernatant. Samples were incubated at 30°C for 1 hr, and were either tested for chromatin remodeling activity or analyzed by Western blotting.

Western blotting and antibody production

Proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and detected by ECL reagents according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Amersham). hSWI3 rabbit polyclonal antiserum was generated by use of GST–hSWI3 fusion protein containing amino acids 672–771. Anti-hBrm rabbit polyclonal antiserum was raised against a peptide that is unique to hBrm (amino acids 282–313). Both anti-hSWI3 and anti-hBrm antibodies were generated by Covance, Inc. Mouse monoclonal anti-Flag M2 and rabbit polyclonal anti-Flag antibodies were purchased from Kodak and Santa Cruz, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Pear, M. Scott, and D. Baltimore for kindly providing the pBabe retroviral vector and Bing cell line, A. Strunnikov and D. Koshland for hSW13 cDNA probe, A. Imbalzano for plasmid TPT and HeLa core histones, J. Hogan and J. Avruch for the GST–His–MEK1 construct, and R. Erikson for plasmids for the expression of wild-type and mutant GST–ERK1. We are grateful to H. Su for technical assistance, Z. Shao, G. Schnitzler, and A. Imbalzano for providing Drosophila embryo extracts and anti-Brg1 sera, and M. Hirschel and J. Moquist from Cellex Biosciences, Inc. for growing our cell lines. We thank T. Gilmore, J. Lee, and members of our laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM48405 to R.E.K. S.S. Was supported by an NIH postdoctoral fellowship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL kingston@frodo.mgh.harvard.edu; FAX (617) 726-5949.

References

- Acharya U, Mallabiabarrena A, Acharya JK, Malhotra V. Signaling via mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1) is required for golgi fragmentation during mitosis. Cell. 1998;92:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80913-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Becker PB, Wu C. Cell-free system for assembly of transcriptionally repressed chromatin from Drosophila embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2241–2249. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulger M, Kadonaga JT. Biochemical reconstitution of chromatin with physiological nucleosome spacing. Methods Mol Genet. 1994;14:241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns BR, Kim YJ, Sayre MH, Laurent BC, Kornberg RD. A multisubunit complex containing the SWI1/ADR6, SWI2/SNF2, SWI3, SNF5, and SNF6 gene products isolated from yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:1950–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns BR, Lorch Y, Li Y, Zhang M, Lacomis L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Du J, Laurent B, Kornberg RD. RSC, an essential, abundant chromatin-remodeling complex. Cell. 1996;87:1249–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Cairns BR, Kornberg RD, Laurent BC. Sfh1p, a component of a novel chromatin-remodeling complex, is required for cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3323–3334. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba H, Muramatsu M, Nomoto A, Kato H. Two human homologues of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SWI2/SNF2 and Drosophila brahma are transcriptional coactivators cooperating with the estrogen receptor and the retinoic acid receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1815–1820. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.10.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté J, Quinn J, Workman JL, Peterson CL. Stimulation of GAL4 derivative binding to nucleosomal DNA by the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Science. 1994;265:53–60. doi: 10.1126/science.8016655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews CM, Alessandrini AA, Erikson RL. Mouse Erk-1 gene product is a serine/threonine protein kinase that has the potential to phosphorylate tyrosine. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:8845–8849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— The primary structure of MEK, a protein kinase that phosphorylates the ERK gene product. Science. 1992;258:478–480. doi: 10.1126/science.1411546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam JD, Martin PL, Shastry BS, Roeder RG. Eurkaryotic gene transcription with purified components. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:582–598. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall AK, Beek SJ, McCallum CM, Tamkun JW, Kalpana GV, Goff SP, Scott MP. The Drosophila snr1 and brm proteins are related to yeast SWI/SNF proteins and are components of a large protein complex. Mol Biol Cel. 1995;6:777–791. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunaief JL, Strober BE, Guha S, Khavari PA, Alin K, Luban J, Begemann M, Crabtree GR, Goff SP. The retinoblastoma protein and BRG1 form a complex and cooperate to induce cell cycle arrest. Cell. 1994;79:119–130. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynlacht BD. Regulation of transcription by proteins that control the cell cycle. Nature. 1997;389:149–152. doi: 10.1038/38225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesfeld JM, Forbes DJ. Mitotic repression of the transcriptional machinery. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl P, Gottesfeld J, Forbes DJ. Mitotic repression of transcription in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:613–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Erikson RL. Constitutive activation of Mek1 by mutation of serine phosphorylation sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:8960–8963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbalzano AN, Kwon H, Green MR, Kingston RE. Facilitated binding of TATA-binding protein to nucleosomal DNA. Nature. 1994;370:481–485. doi: 10.1038/370481a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Bulger M, Pazin MJ, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga JT. ACF, an ISWI-containing and ATP-utilizing chromatin assembly and remodeling factor. Cell. 1997;90:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalpana GV, Marmon S, Wang W, Crabtree GR, Goff SP. Binding and stimulation of HIV-1 integrase by a human homolog of yeast transcription factor SNF5. Science. 1994;266:2002–2006. doi: 10.1126/science.7801128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khavari PA, Peterson CL, Tamkun JW, Mendel DB, Crabtree GR. BRG1 contains a conserved domain of the SWI2/SNF2 family necessary for normal mitotic growth and transcription. Nature. 1993;366:170–174. doi: 10.1038/366170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston RE, Bunker CA, Imbalzano AN. Repression and activation by multiprotein complexes that alter chromatin structure. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:905–920. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H, Imbalzano AN, Khavari PA, Kingston RE, Green MR. Nucleosome disruption and enhancement of activator binding by a human SW1/SNF complex. Nature. 1994;370:477–481. doi: 10.1038/370477a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent BC, Yang X, Carlson M. An essential Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene homologous to SNF2 encodes a helicase-related protein in a new family. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1893–1902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Ross J, Scheppler JA, Franza BR., Jr An in vitro transcription analysis of early responses of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat to different transcriptional activators. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1883–1893. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher B, Eisenman RN. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of the nuclear oncoproteins. Myc and Myb. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:775–784. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.4.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Balbás MA, Dey A, Rabindran SK, Ozato K, Wu C. Displacement of sequence-specific transcription factors from mitotic chromatin. Cell. 1995;83:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgernstern JP, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: High titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchardt C, Yaniv M. A human homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF2/SWI2 and Drosophila brm genes potentiates transcriptional activation by the glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO J. 1993;12:4279–4290. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchardt C, Reyes JC, Bourachot B, Leguoy E, Yaniv M. The hbrm and BRG-1 proteins, components of the human SNF/SWI complex, are phosphorylated and excluded from the condensed chromosomes during mitosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:3394–3402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K. Viewpoint: Putting the cell cycle in order. Science. 1996;274:1643–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjape SM, Kamakaka RT, Kadonaga JT. Role of chromatin structure in the regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:265–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CL, Dingwall A, Scott MP. Five SWI/SNF gene products are components of a large multisubunit complex required for transcriptional enhancement. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:2905–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JC, Muchardt C, Yaniv M. Components of the human SWI/SNF complex are enriched in active chromatin and are associated with the nuclear matrix. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:263–274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riabowol K, Dretta G, Brizuela L, Vandre D, Beach D. The cdc2 kinase is a nuclear protein that is essential for mitosis in mammalian cells. Cell. 1989;57:393–401. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90914-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segil N, Guermah M, Hoffmann A, Roeder RG, Heintz N. Mitotic regulation of TFIID: Inhibition of activator-dependent transcription and changes in subcellular localization. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:2389–2400. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober BE, Dunaief JL, Guha S, Goff SP. Functional interactions between the hBRM/hBRG1 transcriptional activators and the pRB family of proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1576–1583. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukenberg PT, Lustig KD, McGarry TJ, King RW, Kuang J, Kirschner MW. Systematic identification of mitotic phosphoproteins. Curr Biol. 1997;7:338–348. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi-Ichinose C, Ichinose H, Metzger D, Chambon P. SNF2β-BRG1 is essential for the viability of F9 murine embryonal carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5976–5986. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamkun JW, Deuring R, Scott MP, Kissinger M, Pattatucci AM, Kaufman TC, Kennison JA. brahma: A regulator of Drosophila homeotic genes structurally related to the yeast transcriptional activator SNF2/SWI2. Cell. 1992;68:561–572. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90191-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama T, Wu C. Purification and properties of an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling factor. Cell. 1995;83:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga-Weiz PD, Wilm M, Bonte E, Dumas K, Mann M, Becker PB. Chromatin-remodelling factor CHRAC contains the ATPases ISWI and topoisomerase II. Nature. 1997;388:598–602. doi: 10.1038/41587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Xue Y, Zhou S, Kuo A, Cairns BR, Crabtree GR. Diversity and specialization of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Genes & Dev. 1996a;10:2117–2130. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.17.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Côté J, Xue Y, Zhou S, Khavari PA, Biggar SR, Muchardt C, Kalpana GV, Goff SP, Yaniv M, Workman JL, Crabtree GR. Purification and biochemical heterogeneity of the mammalian SWI-SNF complex. EMBO J. 1996b;15:5370–5382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Gottlieb TM, Downes CS, Jackson SP. Mitotic regulation of a TATA-binding protein-containing complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1983–1992. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston F, Carlson M. Yeast SNF/SWI transcriptional activators and the SPT/SIN chromatin connection. Trends Genet. 1992;8:387–391. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90300-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Lieberman PM, Boyer TG, Berk AJ. Holo-TFIID supports transcriptional stimulation by diverse activators and from a TATA-less promoter. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:1964–1974. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]