History of the REMS Program

On September 27, 2007, President George W. Bush signed into law the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA), which authorized the FDA to require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program for drugs and biological agents.1 REMS programs are intended to support the safe use of products for which the risks and benefits need to be carefully weighed in general or in specific patient populations. The FDA can require a REMS program at the time of a product’s approval. If a safety problem is detected after approval, the REMS can be required at any time during a drug’s life cycle.

The decision about whether to require a REMS program is based on the estimated patient population likely to be exposed to the product, the seriousness of the condition being treated by the drug, the expected benefit and duration of treatment, and the safety risk created by use of the drug.2 The results of this analysis determine the need for and the components of the REMS.

The FDAAA legislation authorized several individual requirements, one or more of which may be combined to make up a product-specific REMS program.2 The requirements include:

a medication guide.

a communication plan to disseminate risk information to health care professionals (e.g., Dear Healthcare Professional letters).

elements to ensure safe use.

an implementation system to monitor and evaluate the program’s success.

Several elements to ensure safe use are outlined in the legislation (Table 1). Products can vary greatly in their REMS requirements. As of December 10, 2010, more than 150 drug products had a REMS program.3 Of those drugs, almost all included a medication guide (Table 2). For other products, such as antidepressants as a class, a medication guide may be required outside of a REMS program.4

Table 1.

Elements to Ensure Safe Use

| A REMS program to ensure safe use incorporates one or more of the following elements: |

|

Data from FDA Amendments Act of 2007.2

Table 2.

Drug Products With REMS Programs—Medication Guide Only

| Antiepileptic drugs, selected |

| Carbamazepine (Equetro) |

| Ethosuximide (Zarontin) |

| Ethotoin (Peganone) |

| Gabapentin (Neurontin) |

| Lacosamide (Vimpat) |

| Levetiracetam (Keppra) |

| Lamotrigine (Lamictal) |

| Pregabalin (Lyrica) |

| Primidone (Mysoline) |

| Tiagabine (Gabitril) |

| Topiramate (Topamax) |

| Zonisamide (Zonegran) |

| Antiretrovirals, selected |

| Abacavir (Ziagen) |

| Abacavir/lamivudine (Epzicom) |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) |

| Abacavir/lamivudine/zidovudine (Trizivir) |

| Nevirapine (Viramune) |

| Didanosine (Videx, Videx EC) |

| Telbivudine (Tyzeka) |

| Saquinavir (Invirase) |

| Fluoroquinolones, all |

| Interferon alfa and beta, all |

| Long-acting beta2-agonist combination products, selected |

| Formoterol/budesonide (Symbicort) |

| Salmeterol/fluticasone (Advair) |

| Thiazolidinediones, all |

| Other agents |

| Bupropion (Aplenzin, Wellbutrin) |

| Colchicine (Colcrys) |

| Dabigatran (Pradaxa) |

| Diclofenac oral and topical solutions (Cambia, Pennsaid) |

| Doxepin (Silenor) |

| Fenofibric acid (Trilipix) |

| Mefloquine (Lariam) |

| Methsuximide (Celontin) |

| Metoclopramide oral solution and disintegrating tablets (Metozolv ODT) |

| Milnacipran (Savella) |

| Morphine oral solution |

| Naltrexone (Vivitrol) |

| Olanzapine (Zyprexa) |

| Olanzapine/fluoxetine (Symbyax) |

| Omalizumab (Xolair) |

| Oral bowel prep kits |

| Oxycodone oral solution |

| Pancrelipase (Creon, Pancreaze, Zenpep) |

| Pazopanib (Votrient) |

| Propylthiouracil |

| Quetiapine (Seroquel) |

| Ramelteon (Rozerem) |

| Repository corticotropin (HP Acthar Gel) |

| Ribavirin (Copegus, Rebetol) |

| Rufinamide (Banzel) |

| Sirolimus (Rapamune) |

| Sitagliptin (Januvia, Janumet) |

| Sunitinib (Sutent) |

| Testosterone, topical (AndroGel, Axiron, Testim) |

| Trazodone extended release (Oleptro) |

| Varenicline (Chantix) |

| Zolpidem oral spray (ZolpiMist) |

Data from FDA, as of December 2010. Information for REMS is updated routinely on the FDA Web site.3

Many drugs also include a communication plan. A subset of drugs, including the erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), requires elements to ensure safe use with or without an implementation system (Table 3, page 425). The FDA seeks input from patients and health care practitioners when developing the program design to ensure that it will not be unduly burdensome to patients or the health care system.2

Table 3.

REMS Program Requirements by Drug Product or Class

| Medication Guide | Communication Plan | Elements of Safe Use | Implementation System | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvimopan (Entereg) | X | X | X | |

| Alglucosidase alfa (Lumizyme) | X | X | X | |

| Alosetron (Lotronex) | X | X | X | |

| Armodafinil (Nuvigil) | X | X | ||

| Botulinum toxin A (Botox, Dysport, Xeomin) and B (Myobloc) | X | X | ||

| Buprenorphine transdermal (Butrans) | X | X | ||

| Buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual film (Suboxone) | X | X | X | |

| Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (Xiaflex) | X | X | ||

| Dalfampridine (Ampyra) | X | X | ||

| Denosumab (Prolia) | X | X | ||

| Dronedarone (Multaq) | X | X | ||

| Ecallantide (Kalbitor) | X | X | ||

| Eculizumab (Soliris) | X | X | ||

| Electrolyte containing bowel prep tablets (OsmoPrep, Visicol) | X | X | ||

| Eltrombopag (Promacta) | X | X | X | |

| Endothelin receptor antagonists (Letairis, Tracleer) | X | X | X | |

| Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (Aranesp, Epogen, Procrit) | X | X | X | X |

| Everolimus (Zortress) | X | X | ||

| Fingolimod (Gilenya) | X | X | ||

| Formoterol/mometasone (Dulera) | X | X | ||

| Fentanyl buccal film (Onsolis) | X | X | X | X |

| Glucagon-like peptides (Byetta, Victoza) | X | X | ||

| Hydromorphone extended release (Exalgo) | X | X | ||

| Isotretinoin (Accutane, Amnesteem, Claravis) | X | X | X | |

| Lenalidomide (Revlimid) | X | X | X | |

| Modafinil (Provigil) | X | X | ||

| Morphine/naltrexone (Embeda) | X | X | ||

| Nilotinib (Tasigna) | X | X | ||

| Olanzapine extended release injection (Zyprexa Relprevv) | X | X | X | X |

| Oxycodone extended release | X | X | ||

| Pegloticase (Krystexxa) | X | X | ||

| Prasugrel (Effient) | X | X | ||

| Quinine (Qualaquin) | X | X | ||

| Romiplostim (Nplate) | X | X | X | X |

| Sacrosidase (Sucraid) | X | X | X | |

| Salmeterol (Serevent) | X | X | ||

| Telavancin (Vibativ) | X | X | ||

| Teriparatide (Forteo) | X | X | ||

| Tetrabenazine (Xenazine) | X | X | ||

| Thalidomide (Thalomid) | X | X | X | |

| Tocilizumab (Actemra) | X | X | ||

| Tolvaptan (Samsca) | X | X | ||

| Tumor necrosis factor antagonists: certolizumab (Cimzia), etanercept (Enbrel), adalimumab (Humira), infliximab (Remicade), golimumab (Simponi) | X | X | ||

| Ustekinumab (Stelara) | X | X | ||

| Vigabatrin (Sabril) | X | X | X | X |

Data from FDA, as of December 2010. Information for REMS is updated routinely on the FDA Web site.3

The Use of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents In Oncology

ESAs have been widely used in cancer patients on the basis of data showing that they decreased transfusion requirements. A 2006 meta-analysis of more than 9,000 patients receiving ESAs, with and without concurrent antineoplastic therapy, reported a 36% decreased need for red blood cell transfusions.5 Unfortunately, the authors also found a 67% increase in thromboembolic events (transient ischemic attacks, stroke, pulmonary emboli, deep-vein thrombosis, and myocardial infarction) for those receiving ESAs, conflicting with results of a previous publication.6 This earlier analysis, published in 2005,6 also indicated a trend toward increased survival that was not supported by the subsequent 2006 study.5

A meta-analysis, published in 2008 by Bennett et al., reinforced the elevated thromboembolic risk associated with ESA use compared with a placebo (7.5% vs. 4.9%, respectively).7 The authors also found an increased mortality risk with ESAs (hazard ratio [HR], 1.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.20).

A 2009 update to the 2006 meta-analysis5 revealed increased mortality with the use of ESAs (combined HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06–1.3) and decreased survival (combined HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1–1.12) during the active study period.8 There was no statistically significant increase in mortality (combined HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.98–1.24) or decrease in overall survival (combined HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.97–1.11) in the subgroup of patients receiving concomitant chemotherapy and ESAs.

In addition to the meta-analyses of studies investigating ESAs, the FDA Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) met three times to discuss the findings and the future place of ESAs in the management of patients with cancer. At the first meeting in 2004, two trials with adverse findings were reviewed (Table 4, page 426): Evaluation of NeoRecormon on outcome in Head And Neck Cancer in Europe (ENHANCE)9 and the Breast Cancer Erythropoietin Survival Trial (BEST).10 Based on these trials and previous data regarding thromboembolic events, the FDA-approved labeling of ESAs was updated to warn of the increased risks of thrombosis and tumor promotion.

Table 4.

Summary of Trials of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents (ESAs) Reviewed by the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee

| Trial | Study Design | Selected Results |

|---|---|---|

| Reviewed in 2004 | ||

| ENHANCE9 |

|

ESA use was associated with:

|

| BEST10 |

|

Study was stopped early; higher mortality rates in the ESA group than in the placebo group:

|

| Reviewed in 2007 | ||

| EPO CAN-2011 |

|

Study was stopped early; higher mortality rates in the ESA group than in controls:

|

| Amgen study 2001-010312 |

|

ESA use was associated with:

|

| Amgen study 2000-016113 |

|

ESA use was associated with:

|

| DAHANCA 1014 |

|

ESA use was associated with:

No statistically significant difference in overall survival |

| Reviewed in 2008 | ||

| GOG-19115 |

|

Study was stopped early; concerns about an increased rate of thromboembolic events with ESAs:

ESA use was associated with a numerical, but not a statistically significant, decrease in:

|

| PREPARE16 |

|

An unplanned interim analysis after a median follow-up period of 3 years showed an association of ESA use with:

|

CI = confidence interval; Hb = hemoglobin; HR = hazard ratio.

Trials: BEST = Breast Cancer Erythropoietin Survival Trial; DAHANCA = Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group; ENHANCE = Evaluation of NeoRecormon on outcome in Head And Neck Cancer in Europe; EPO CAN-20 = Epoetin Alfa in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer; GOG = Gynecologic Oncology Group; PREPARE = Preoperative Epirubicin Paclitaxel Aranesp.

In 2007, the ODAC discussed four additional trials that showed adverse outcomes: Epoetin Alfa in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer (EPO CAN-20),11 Amgen studies 2001-010312 and 2000-0161,13 and the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA 10)14 (see Table 4). This review resulted in the addition of a boxed warning to the labeling of ESAs regarding an increased risk of death, more rapid tumor progression, and serious cardiovascular and thromboembolic events.

In 2008, the ODAC was convened to review the results of two additional trials: the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG-191)15 and the Preoperative Epirubicin Paclitaxel Aranesp (PREPARE16) study. Based on these trials and the earlier literature showing adverse outcomes, the ODAC recommended limiting the use of ESAs to patients receiving palliative treatment. The ODAC also recommended that the FDA require informed consent or a patient agreement before ESAs could be administered. The FDA-approved labels were subsequently revised to state that ESAs were not recommended when the intent of chemotherapy was to cure and when a REMS program was initiated.

In response to published data, national guidelines have been updated. The 2010 American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society of Hematology guideline recommends ESAs as an option when hemoglobin levels are below 10 g/dL during chemotherapy.17 The guideline does not include a specific hemoglobin target; instead, it recommends maintaining hemoglobin at the lowest level required to avoid a transfusion. Notably, the guideline differs from the FDA-approved labeling by stating that limiting the use of ESAs to palliative chemotherapy regimens is a clinical judgment and not expressly supported by the literature. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) defined the appropriate setting for ESAs to apply only to patients receiving chemotherapy in the palliative setting with a hemoglobin level of less than 10 g/dL and further recommend discontinuing ESAs within eight weeks of the last chemotherapy dose.18

ESA APPRISE and an Approach to Compliance

In February 2010, based on the ODAC’s recommendations and the FDA’s subsequent action, Amgen and Centocor Ortho Biotech announced that the FDA had approved a REMS program called Assisting Providers and cancer Patients with Risk Information for the Safe use of ESAs (the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program).19 This program incorporates a medication guide, a communication plan, elements to ensure safe use, and an implementation system.20

Medication Guide

The original REMS for ESAs included a requirement that a medication guide be distributed to each patient when an ESA was to be dispensed.20 There was no specific direction with regard to the practice setting (i.e., inpatient or outpatient) or the frequency with which guides should be distributed (i.e., upon therapy initiation or with every drug administration).

In February 2011, the FDA issued a draft guidance explaining its approach to discretionary enforcement of the REMS regulations.21 Although not yet formally in effect as of this writing, the draft guidance specifies requirements for in-patient and outpatient sites and when medication guides must be distributed. For hospitalized patients, a guide is not mandatory unless the patient or patient’s agent requests it. Instead, providing patient information, including appropriate use, potential side effects, and follow-up by a health care professional in the course of care, is considered sufficient to meet the regulatory intent. In an outpatient setting, in which the ESA is dispensed to a health care professional to administer to the patient, the medication guide must be distributed upon request, at the first time drug is dispensed, and when the guide’s content has been substantively changed.

The FDA guidance does not affect the duty of the hospital to inform a patient of the REMS program. Although distribution of the actual medication guide is not mandated for each patient with each drug administration, a review of the information must still be included for each patient each time.

(Note: Distribution of the guide is required for all uses of ESAs, whereas other elements of ESA APPRISE are unique to patients with cancer.)

Some logistical considerations are associated with this process and must be addressed by each hospital, such as which member of the health care team is responsible for reviewing the information with the patient (nurse, pharmacist, or physician) and whether the medication guide must be used to facilitate discussion. If the guide is used, the process by which it is stored and retrieved must also be addressed.

For instance, the medication guides are five pages long, they are not supplied in a 1:1 ratio with the product, and they are subject to updates. At St. Vincent Indianapolis Hospital, the nurse reviews the guide with the patient. The guide is printed by the pharmacy from the manufacturer’s Web site at the time of dispensing, It is then sent with the ESA to ensure that the most recent version is used, thereby eliminating the need to store paper copies. The medication guide is distributed with each drug administration to each patient so that the content provided and the method of dissemination are consistent.

Communication Plan

The responsibility of the communication plan rests with the manufacturer. The Dear Healthcare Provider letters and other materials can be accessed at www.esa-apprise.com.20

Elements to Ensure Safe Use20

Three of the elements to ensure safe use are incorporated into the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program: (1) health care provider training and certification, (2) hospital certification, and (3) dispensing following the documentation of safe-use conditions. All prescribers who plan to order ESAs for cancer patients must receive training and must enroll in ESA APPRISE. The manufacturer maintains an on-line list of enrolled prescribers through an independent third party. The hospital must appoint a designee to receive training and enroll in APPRISE on behalf of the institution. At our hospital, the designee is the director of pharmacy.

Training, which is available on the manufacturer’s Web site, includes a review of the risks of using ESAs in cancer patients. Enrollment includes an agreement to conform to the mandates of ESA APPRISE. The hospital designee is responsible for establishing and overseeing a process that includes verification of prescriber enrollment in the program as well as patient and prescriber discussions of risks and benefits before ESAs are dispensed.

One of the elements of ESA APPRISE is a formal, documented discussion between a certified prescriber and the patient regarding the risks and benefits of ESA use in cancer. Both parties sign an acknowledgment form. Outside the hospital, these forms are faxed to a central repository and are also maintained in the patient’s medical record. For in-hospital use of ESAs, forms are not submitted to a central repository; they are provided to the hospital designee only to validate that the discussion has occurred before an ESA has been dispensed. Completion of the form does not constitute patient enrollment in any registry or program; it serves only as documentation of the required discussion between prescriber and patient.

We’ve noted many logistical problems involving the acknowledgment form in our institution, which is a community hospital without an integrated electronic health record (EHR) system. In the REMS program, a prescriber is required to complete the form with the patient for each course of therapy, although many times therapy is initiated in the outpatient setting and continued in the hospital. The hospital could choose to require a copy of the acknowledgment form to verify completion. If so, the form must travel from the office to the hospital, or it must be completed again in the hospital. The office might be unable to provide a copy during off-hours, or the physician might be unavailable to complete it again.

According to the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program, it is the duty of the prescriber to complete the acknowledgment form with the patient. This task cannot be delegated to other members of the health care team. Verification also needs to occur with each admission, and completed forms must be stored and retrieved by the pharmacist or must be provided again by the office or physician with each admission.

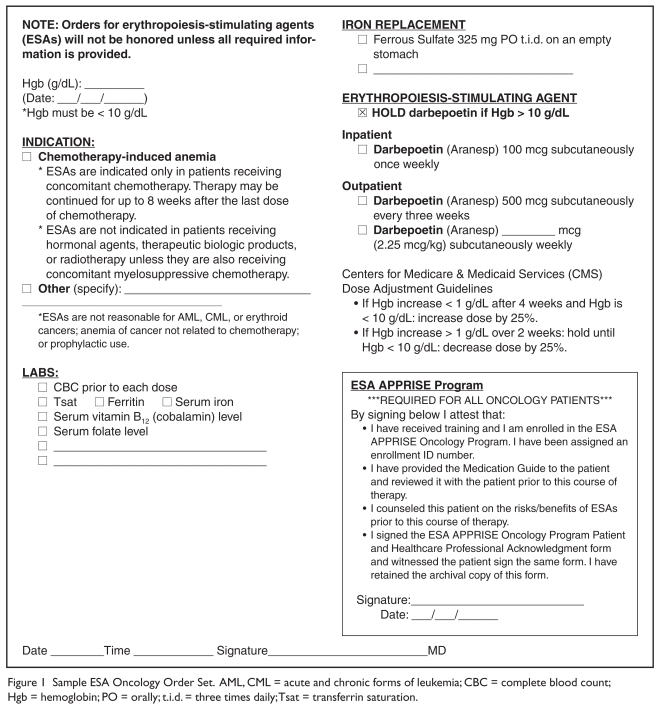

Our hospital has opted for a different approach and has determined that a specific medication order set for ESAs is the best approach in treating cancer patients (Figure 1). Included in the order set is a physician’s attestation that the medication guide has been reviewed, the risks and benefits have been discussed, and the prescriber and patient have signed the acknowledgment form. Following confirmation that the prescriber is registered with the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program, this order set serves as our hospital’s documentation of compliance. The patient acknowledgment form, in addition to the medication order set, may be submitted to the pharmacy; however, this is not required, because the physician’s attestation serves as a surrogate.

Figure 1.

Sample ESA Oncology Order Set. AML, CML = acute and chronic forms of leukemia; CBC = complete blood count; Hgb = hemoglobin; PO = orally; t.i.d. = three times daily; Tsat = transferrin saturation.

Implementation

The manufacturer is responsible for confirming compliance with ESA APPRISE. This is achieved through a series of random on-site audits of enrolled hospitals. Those hospitals that are not enrolled or that are not in compliance may not have access to ESAs.20

Conclusion

REMS programs represent a new facet of drug safety regulation. With a growing number of programs and a wide variety of requirements within the programs, hospitals may be challenged to meet the criteria for compliance. The ESA APPRISE Oncology Program represents a difficult challenge, in that ESAs may be high-use agents, and the elements to ensure safe use present logistical considerations for hospital pharmacy departments.

References

- 1.Identification of drug and biological products deemed to have risk evaluation and mitigation strategies for purposes of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007. Fed Register. 2008;73(60):16313–16314. [Google Scholar]

- 2.FDA Full text, FDA Amendments Act of 2007. Available at: www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/FederalFoodDrugandCosmeticActFDCAct/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/FoodandDrugAdministrationAmendmentsActof2007/FullTextofFDAAALaw/default.htm. Accessed December 21, 2010.

- 3.FDA Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm111350.htm. Accessed December 10, 2010.

- 4.Drug products with medication guides. Pharm Lett Prescriber Lett. 2006;22(220331) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohlius J, Wilson J, Seidenfeld J, et al. Recombinant human erythropoietins and cancer patients: Updated meta-analysis of 57 studies including 9353 patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:708–714. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohlius J, Langensiepen S, Schwarzer G, et al. Recombinant human erythropoietin and overall survival in cancer patients: Results of a comprehensive meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:489–498. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett CL, Siver SM, Bjulbegovic B, et al. Venous thromboembolism and mortality associated with recombinant erythropoietin and darbepoetin administration for the treatment of cancer-associated anemia. JAMA. 2008;299:914–924. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohlius J, Schmidlin, Brillant C, et al. Recombinant human erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and mortality in patients with cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1532–1542. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60502-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henke M, Laszig R, Rube C, et al. Erythropoietin to treat head and neck cancer patients with anaemia undergoing radiotherapy: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:1255–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leyland-Jones B, Semiglazov V, Pawlicki M, et al. Maintaining normal hemoglobin levels with epoetin alfa in mainly nonanemic patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving first line chemotherapy: A survival study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5960–5972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright JR, Ung YC, Julian JA, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of erythropoietin in non-small-cell lung cancer with disease-related anemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1027–1032. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith RE, Aapro MS, Ludwig H, et al. Darbepoetin alfa for the treatment of anemia in patients with active cancer not receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy: Results of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1040–1050. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedenus M, Adriansson M, San Miguel J, et al. Efficacy and safety of darbepoetin alfa in anaemic patients with lymphoproliferative malignancies: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:394–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overgaard J, Hoff C, Sand Hansen H, et al. Randomized study of the importance of novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein (Aranesp) for the effect of radiotherapy in patients with primary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC): The Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group DAHANCA 10 randomized trial. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2007;5:7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas G, Ali S, Hoebers FJP, et al. Phase III trial to evaluate the efficacy of maintaining hemoglobin levels above 120 g/dl with erythropoietin vs. above 100 g/dl without erythropoietin in anemic patients receiving concurrent radiation and cisplatin for cervical cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FDA Background information for the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting, March 13, 2008. Available at: www.fda.gov/ohrms/DOCKETS/ac/08/briefing/2008-4345b2-05-AMGEN.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2010.

- 17.Rizzo JD, Brouwers M, Hurley P, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society of Hematology clinical practice guideline update on the use of epoetin and darbepoetin in adult patients with cancer. Blood. 2010;116:4045–4059. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Decision memo for erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) for non-renal disease indications (CAG 00383N) Available at: https://www.cms.gov/mcd/viewdecisionmemo.asp?from2=viewdecisionmemo.asp&id=203&. Accessed December 20, 2010.

- 19.Amgen and Centocor Ortho Biotech Products Finalize ESA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) With FDA. Feb 16, 2010. Available at: www.amgen.com/media/media_pr_detail.jsp?releaseID=1391301. Accessed December 22, 2010.

- 20.ESA APPRISE Oncology Program. Amgen. Available at: https://www.esa-apprise.com/ESAAppriseUI/ESAAppriseUI/default.jsp. Accessed December 22, 2010.

- 21.Guidance for Industry. Medication Guides—Distribution Requirements and Inclusion in Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS). Draft Guidance, February 2011. Available at: www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM244570.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2011.