INTRODUCTION

This Product Profiler introduces health care professionals to Privigen®, Immune Globulin Intravenous (Human), 10% Liquid. Privigen® has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as replacement therapy for the treatment of primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD). This includes, but is not limited to, the humoral immunodeficiency in congenital agammaglobulinemia, common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and severe combined immunodeficiencies (SCIDs) (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011). Privigen® is also indicated for the treatment of patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) to raise platelet counts (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Replacement immunoglobulin therapy is the standard of care for primary humoral immunodeficiency disorders and has also been used for immunomodulatory treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (Looney 2006, Shehata 2010). Immunoglobulins are isolated from pooled plasma donated by thousands of individuals, which ensures that a broad spectrum of antibodies is contained in the final preparation (Looney 2006). The resulting fractionated blood product provides immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, with minimal IgA and IgM constituents. IgG therapy has been used for the treatment of PIDD since the 1950s (Shehata 2010). Initially, IgG preparations were administered via intramuscular (IM) or subcutaneous (SC) routes. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) was introduced in the 1970s. Eventually, IM administration of IgG was superceded by IV and SC treatment because of the latter’s improved tolerability (Shehata 2010).

Today, several IVIg products are approved by the FDA for an array of clinical indications: 1) to treat PIDD; 2) to increase platelet counts in patients with ITP to prevent or control bleeding; 3) to prevent bacterial infections in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia or recurrent bacterial infections, or both, associated with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL); 4) to prevent coronary artery aneurysms in patients with Kawasaki disease (KD); 5) to prevent infections, pneumonitis, and acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after bone marrow transplantation in adults aged ≥20 years; and 6) to reduce the frequency and severity of bacterial infections in children with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (Orange 2006, Looney 2006).

The following text presents an overview of PIDD and chronic ITP; current treatment options for these disorders; a review of the evidence-based literature supporting the FDA-approved indications for Privigen®; product information pertaining to Privigen®, including clinical trial data and safety information; and considerations for P&T committee decisions regarding this product.

DISEASE OVERVIEW: PRIMARY IMMUNODEFICIENCY

Incidence and Prevalence

PIDD is recognized as an inherited, heterogeneous disorder of the immune system that results in increased rates and severity of infections, immune dysregulation associated with autoimmune diseases, and the development of malignancies (AAAAI 2011, Bonilla 2005, Lindegren 2004). Repeated infections due to PIDDs can lead to severe organ damage, repeated hospitalizations, diminished quality of life (QOL), and reduced life expectancy (AAAAI 2011, Garcia 2010). PIDDs are clinically similar to, but distinct from, secondary immunodeficiencies that may develop in response to viral infections, immunosuppressive therapies, systemic therapy for autoimmune diseases, or chemotherapy for malignancies (Bonilla 2005, Lindegren 2004). At least 50% of all primary immunodeficiency syndromes are primary antibody deficiency disorders (Herriot 2008).

PIDD is more likely to occur in persons aged <20 years, and 70% of cases affect males because of an X-linked recessive pattern of inheritance (Lindegren 2004). It has been estimated that there are currently at least 150 different types of PIDDs, with more than 60 of these involving impaired production of antibodies (Buckley 2009, Orange 2011a). Fewer than 20 PIDDs account for more than 90% of cases (Lindegren 2004).

PIDDs are considered rare, although accurate estimates of incidence or prevalence are unavailable (Boyle 2007, Kumar 2006). Registries established by countries to collect information about PIDDs are believed to underestimate the true prevalence of PIDD for several reasons, among them lack of recognition/diagnosis by clinicians and altered presentation of the disease because of widespread antibiotic use (Kumar 2006, Lindegren 2004).

The incidence and prevalence of the different types of PIDD are widely variable. For example, selective IgA deficiency is recognized as the most common PIDD, with an estimated frequency of 1:223 to 1:1,000 individuals in the US (Kumar 2006, Yel 2010). Higher incidence rates of 1:500 to 1:700 were reported for white individuals of European descent (NPIRC 2011a). CVID affects an estimated 1 in 50,000 persons, and SCID, the most serious primary immune disorder, has an estimated incidence of 1 in 1,000,000 (NPIRC 2011b, 2011c).

Thus, the true incidence and prevalence of PIDD are largely unknown. However, the two most common types are selective IgA deficiency and CVID.

Etiology

Defects in approximately 150 genes are associated with the development of PIDD (Ortutay 2009). Table 1 lists gene mutations that have been identified in key PIDDs (Herriot 2008). These mutations provide researchers with valuable insights into the role of genes in the development and function of immune cells and in immune-related homeostatic mechanisms (Fischer 2004).

TABLE 1.

Gene mutations in key PIDDs

| Disorder | Inheritance | Gene mutations |

|---|---|---|

| Severe reduction in all immunoglobulin isotypes and absent B cells: | ||

| X-linked agammaglobulinemia | XL | Btk |

| Autosomal recessive agammaglobulinemia | AR | μ

chain Igα Igβ λ5 BLNK |

| Severe reduction in at least 2 isotypes with normal or low B cell numbers: | ||

| Common variable immunodeficiency | AR |

ICOS CD19 BAFFR SBDS |

| AD or AR | TACI | |

| Severe reduction in IgG and IgA with normal or increased IgM and normal B cell numbers: | ||

| CD40 ligand deficiency | XL | CD40XL |

| CD40 deficiency | AR | CD40 |

| AID deficiency | AR | AICDA |

| UNG deficiency | AR | UNG |

| Individual isotype or light-chain deficiencies with normal B cell numbers: | ||

| Immunoglobulin heavy-chain deletions | AR | 14q32 deletions |

| K chain deficiency | AR | K constant gene |

| Selective IgA deficiency | AD or AR | TACI |

XL = X-linked; Btk = Bruton tyrosine kinase; AR = autosomal recessive; BLNK = B cell linker protein; ICOS = inducible co-stimulator; BAFFR = B cell activation factor of the TNF family receptor; SBDS = Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome gene; AD = autosomal dominant; TACI = transmembrane activator and calcium-modulating ligand interactor; AICDA = activation-induced cytidine deaminase; UNG = uracil-DNA glycolase.

Source: Adapted from Herriot 2008.

Pathophysiology

The human body depends on the immune system for protection against invading pathogens (Haynes 2008). There are two basic types of immunity: innate and adaptive (Haynes 2008, Chaplin 2006). The innate immune system, evolved over millions of years, consists of physiologic barriers against invading pathogens (NIAID 2011) along with a variety of host cells bearing gene-encoded receptors that recognize and destroy disease-causing agents (Haynes 2008, Chaplin 2006). The body’s front-line defenses against pathogens include the skin and the respiratory and digestive tracts. Intact skin forms a virtually impenetrable barrier to invaders. Microbes entering the nose often cause the nasal surfaces to secrete protective mucus, and attempts to enter the nose or lungs can trigger a sneeze or cough reflex, which forces microbial invaders out of the respiratory passageways. The stomach contains a strong acid that destroys many pathogens that are swallowed with food. Mucosal surfaces also secrete immunoglobulin A (IgA), a special class of antibody that is often the first type of antibody to encounter an invading microbe. If pathogens are able to bypass the body’s front-line physiologic barriers, they are confronted by a cellular defense system, which is ready to attack without regard for specific antigen markers (NIAID 2011). Key players in this system include NK cells, phagocytes, and complement (a group of proteins that produce inflammation in the presence of infection) (Haynes 2008, NIAID 2011, Blaese 2007).

Unlike the innate immune system, adaptive immunity is characterized by the ability to precisely target invading pathogens (Chaplin 2006). In the adaptive immune response, gene elements are rearranged on the surfaces of B and T lymphocytes to create antigen-binding molecules with high specificity for individual microbial and environmental structures (Haynes 2008, Chaplin 2006). Adaptive immunity consists of both cellular and humoral (antibody) immune functions. In cellular immunity, cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize and destroy virus-infected or foreign cells (Haynes 2008, Chaplin 2006). In humoral immunity, B cells produce antibodies in response to specific antigens (Haynes 2008). A key feature of the adaptive immune response is the production of long-lived cells that can repeat their effector functions when they encounter an antigen for the second time (Chaplin 2006).

The innate and adaptive immune systems usually work together, with innate responses representing the body’s first line of defense. Adaptive immunity “kicks in” several days later as antigen-specific T and B lymphocytes become activated (Chaplin 2006). Synergy between the innate and adaptive immune systems is crucial for an effective immune response (Chaplin 2006).

Table 2 describes key components of the body’s immune system and their functions.

TABLE 2.

Key Components of the Immune System

| Component | Functions |

|---|---|

| B lymphocytes |

|

| T lymphocytes |

|

| Natural killer cells |

|

| Phagocytes |

|

| Complement system |

|

Sources: Adapted from Blaese 2007, Haynes 2008, Shier 2010.

PIDDs are classified according to the immune mechanisms that are dysfunctional or hypofunctional (Table 3) (Merck Manual 2010). In the adaptive immune system, defective immune functions include humoral (antibody) deficiencies, cellular deficiencies, or a combination of both. In the innate immune system, defects can include phagocyte and complement deficiencies (Merck Manual 2010).

TABLE 3.

Classification of Immune System Component Defects

| Type of component defect | Description | % of PIDD disorders | Common associated disorders |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-cell defects |

|

50–60% |

|

| T-cell defects |

|

5–10% |

|

| Combined B- and T-cell defects |

|

20% |

|

| Natural killer-cell defects |

|

NA | NA |

| Phagocytic-cell defects |

|

10–15% |

|

| Complement defects |

|

≤2% |

|

CVID = common variable immunodeficiency; Ig = immunoglobulin; XLA = X-linked agammaglobulinemia; ZAP-70 = Z-associated protein 70.

Sources: Adapted from Bonilla 2005, Merck Manual 2010.

Clinical Presentation and Evaluation

The hallmark feature of PIDDs is an increased susceptibility to, and severity of, upper and lower respiratory bacterial infections, such as sinusitis, otitis media, bronchitis, or pneumonia, in the absence of other known or suspected contributing factors (e.g., smoking) (Buckley 2009, Herriot 2008, Wood 2007). Patients with PIDDs are at increased risk of multiple or recurrent infections, infections that are refractory to treatment, unusually severe infections, or infections associated with opportunistic pathogens (Blaese 2007, Kumar 2006). Commonly affected sites of persistent or recurrent infections include the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, skin, eyes, skeleton, and central nervous system (Herriot 2008). Table 4 presents estimated infection rates in patients with PIDDs.

TABLE 4.

Estimated Rates of Infection by Site in Patients With PIDDs

| Site of Infection | % (Range) |

|---|---|

| Respiratory/chest (including pneumonia, excluding bronchitis) | 37.0–90.0 |

| Recurrent sinusitis | 19.0–98.0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 6.0–38.0 |

| Cutaneous | 1.0–13.0 |

| Central nervous system/meningitis | 2.0–9.0 |

| Septic arthritis/osteomyelitis | 1.0–7.0 |

| Ophthalmic | 1.4–10.0 |

Source: Adapted from Wood 2009.

While most cases of PIDD are characterized by an increased susceptibility to infections, these patients may develop other clinical disorders, particularly autoimmune diseases, such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia (Bussone 2009, Wood 2007).

Nonspecific features of PIDD include arthropathy and tissue abnormalities, such as lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (Herriot 2008, Wood 2007). In children, symptoms of antibody deficiency may include failure to thrive, recurrent pyrexia of unknown origin, coping problems at school, poor attendance at school, and recurrent respiratory and GI tract infections (Wood 2007). In addition, individuals with PIDD may demonstrate a poor clinical response to vaccinations, such as immunization against Haemophilus influenzae (Herriot 2008).

The Jeffrey Modell Foundation has published a list of warning signs to help physicians in diagnosing cases of PIDD (Jeffrey Modell Foundation 2009). These signs are described in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

10 Warning Signs of Primary Immunodeficiency

|

Source: Jeffrey Modell Foundation 2009. Reproduced with permission.

Individuals with antibody deficiency may begin to show symptoms of the disorder as early as 7 to 9 months after birth, when maternal antibodies have decreased to below protective levels (Ballow 2002). Most PIDDs (>80%) are diagnosed by the age of 20 years (Kumar 2006, Paul 2002).

A definitive diagnosis of PIDD requires a thorough medical history and physical examination to identify the presence of antibody deficiency and to distinguish between primary and secondary disease (de Vries 2006, Wood 2009). Laboratory evaluations include a complete blood count with differential and platelet count (Paul 2002, Cooper 2003). In addition, an assessment of serum immunoglobulin levels is recommended for patients with a suspected PIDD (Paul 2002, Wood 2009).

Early recognition and referral of patients with suspected PIDD are important since timely initiation of appropriate therapies can prevent or reduce infections as well as prevent the development of systemic complications (Wood 2009). Unfortunately, many patients do not benefit from diagnosis early in life. Among respondents to the third national Immune Deficiency Foundation (IDF) survey of patients with PIDDs, conducted in 2007, only 27% of respondents were diagnosed by the age of 6 years; 51% were not diagnosed until age 30 years or older, and 26% were not diagnosed until age 45 years or older (IDF 2009a).

Effects of PIDD on Health Outcomes and Quality of Life

Despite appropriate therapy, patients with PIDDs are at increased risk of developing organ-specific and systemic complications (Wood 2009). In the 2007 IDF survey, 49% of respondents reported significant, permanent functional impairment prior to their initial diagnosis; 32% indicated permanent loss of lung function, 16% indicated impaired digestive function, and 13% reported permanent loss of hearing (IDF 2009a). Similar results were obtained in a 2008 IDF survey of treatment preferences among PIDD patients, with respondents reporting permanent impairment of their lungs (37%), digestive system (17%), and hearing (13%) (IDF 2009b). In the 2007 survey, delayed diagnoses were associated with higher rates of permanent impairment (IDF 2009a).

The challenges of diagnosing and treating PIDDs can be a significant source of stress and life disruption, with a major impact on the physical and psychologic well-being of patients, caregivers, and family members (Buckley 2009). In the 2007 IDF survey, 26% of respondents described their health status as fair, and 10% indicated poor or very poor health (IDF 2009a). The health-status ratings of patients with PIDDs in the 2007 IDF survey were lower compared with responses from an age-matched US population in the National Health Interview Survey. A health status of good or better was reported by 72.8% of respondents with no permanent functional impairments compared with 26.2% of those with 3 or more impairments (IDF 2009a).

Cost Burden of PIDD

The direct economic impact of the diagnosis, treatment, and long-term care of patients with PIDDs is substantial and can include such factors as the use of antimicrobial agents, hospitalization, and treatment of systemic complications (Simoens 2009).

The cost of care for undiagnosed and untreated individuals with PIDD is likely to be considerably higher than the direct medical costs associated with the care of diagnosed patients. In 2007, physician-experts were surveyed to determine the health care costs of undiagnosed/untreated PIDD versus diagnosed/treated disease (Modell 2007). The findings from this study indicated that the average annual cost of health care for an undiagnosed individual with PIDD was $102,736, compared with $22,696 for a diagnosed patient. The diagnosis of patients with underlying PIDD was estimated to save an average of $79,942 per patient per year (Modell 2007). The National Institutes of Health (NIH) have estimated that there are at least 500,000 cases of undiagnosed PIDD in the US (Modell 2007).

DISEASE OVERVIEW: CHRONIC IMMUNE THROMBOCYTOPENIC PURPURA

Incidence and Prevalence

Using the Integrated Healthcare Information System data base, which contains demographic and health information for more than 70 million patients in the US, individuals enrolled in participating health plans between 2002 and 2006 were assessed for the incidence and prevalence of chronic ITP, according to appropriate ICD-9 codes (Feudjo-Tepie 2008). The adjusted diagnosed prevalence rate for chronic ITP among adults aged 18 years or older was 23.6 per 100,000 population. This was equivalent to 52,700 adults with chronic ITP, based on 2005 census population estimates. Age- and gender-adjusted prevalence rates were 20.3 per 100,000 persons, or 60,200 cases, in analyses based on the total population, which included individuals aged <18 years. The prevalence of chronic ITP increased with age and was higher for women than for men.

Rates of chronic ITP in children are generally low, with an estimated annual incidence of 0.46 per 100,000 children and an estimated prevalence of 4.6 per 100,000 children (Gernsheimer 2008). Evidence suggests that children aged 8 to 14 years are more likely to develop chronic ITP compared with those aged ≤7 years (Gernsheimer 2008).

Etiology

ITP is an acquired autoimmune disorder caused by inadequate production and increased destruction of platelets (Pruemer 2009, Gernsheimer 2009, Cines 2002). The disease can be acute (lasting ≤6 months) or chronic (>6 months) (Cines 2002). ITP affects all ages and ethnic groups, and women have a 2- to 3-fold greater risk of developing the disease compared with men. The predominance of women is especially apparent in the 30 to 60 age group (Pruemer 2009, PDSA 2011b). Chronic ITP is more common in adults and persists for at least 6 months in the absence of other abnormalities (Gernsheimer 2009). Children are usually diagnosed at a young age (approximately 5 years), and disease onset is characterized by the sudden appearance of petechiae or purpura after an infectious illness (Cines 2002). The condition spontaneously resolves in 80% to 85% of children within 6 months, regardless of the therapeutic intervention (Cines 2002, Gernsheimer 2008). A small proportion (15% to 20%) of children develops chronic ITP that resembles the adult form of the disease (Gernsheimer 2008).

Infectious causes of ITP include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and Helicobacter pylori infection (Stasi 2009). Before HIV infection was treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), HIV thrombocytopenia occurred in 5% to 30% of patients infected with HIV-1, with a positive correlation between thrombocytopenia and the progression of immunosuppression due to HIV (Stasi 2009). In several cross-sectional studies, the overall prevalence of HCV was 20% in adult patients with ITP (Stasi 2009). A comparison of the incidence rates of ITP among HCV-infected and uninfected US veterans showed that HCV was associated with an increased risk of ITP, with a hazard ratio of 1.8 regardless of treatment status (Stasi 2009). Evidence has shown that the eradication of H. pylori can improve platelet responses in adults with chronic ITP (Stasi 2009). The overall rate of H. pylori infection was 62.3% across more than two dozen studies of adult ITP patients, conducted mostly in Japan and Italy (Stasi 2009).

Pathophysiology

ITP is an autoimmune disease characterized by the development of platelet autoantigens (Cines 2002, Pruemer 2009). This, in turn, results in the destruction or impaired production of platelets, leading to thrombocytopenia (Pruemer 2009). As platelet membrane proteins become antigenic, the immune system responds by producing autoantibodies directed against glycoprotein complexes on platelet surfaces (Cines 2002, Gernsheimer 2009, Pruemer 2009). These autoantibodies have the ability to attach to circulating platelets, which are then removed from the spleen and liver via the reticuloendothelial system (Gernsheimer 2009).

Cytotoxic T cells also play a role in disrupting the production of new platelets (Gernsheimer 2009, Pruemer 2009). Specifically, CD3+ lymphocytes show higher expression of cytotoxic genes, including tumor necrosis factor, perforin, and granzyme A and B. High numbers of CD56+ CD3− NK cells are detected in patients with treatment-dependent ITP and in those who do not respond to treatment. In addition, a high expression of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules is present in patients with refractory ITP. These findings suggest that NK cells contribute to the pathogenesis of ITP through the destruction of IgG-coated targets (Gernsheimer 2009). Megakaryocyte abnormalities, antibody-induced inhibition of megakaryocyte production and growth, an improper response of the bone marrow to ongoing platelet destruction, and deficiencies in thrombopoietin receptor signaling are all thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic ITP as platelet production is reduced (Pruemer 2009).

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

While ITP may be asymptomatic in some patients, the most commonly reported symptom is mucocutaneous bleeding, which manifests as purpura, epistaxis, or menorrhagia, or as oral mucosal, GI, or (in the most severe cases) intracranial hemorrhage (Pruemer 2009). Platelet counts generally remain at one third to one half the normal value of 150 ×109/L but can drop to <10 ×109/L; such dramatic declines in the platelet count may follow viral infection (Gernsheimer 2008).

Chronic ITP may persist for as long as 30 years, but the disease has a generally favorable prognosis for patients who respond to treatment. The risk of bleeding increases with age; a meta-analysis has suggested that age-adjusted bleeding risks are 0.004 per patient-year for individuals aged <40 years, 0.012 per patient-year for patients aged 40 to 60 years, and 0.130 for patients aged >60 years (Gernsheimer 2008).

The diagnosis of ITP is one of exclusion; when all other causes of low platelet counts have been ruled out, then the diagnosis is ITP (PDSA 2011a). Other causes of low platelets include disseminated intravascular coagulation, vitamin deficiency, infection (e.g., HIV and HCV), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, IgA deficiency, common variable hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphoproliferative diseases, the use of certain medications, chronic liver disease, and primary bone marrow disease (Cines 2002, Gernsheimer 2008, Pruemer 2009). A history and physical examination are essential, as are a complete blood count and examination of the peripheral blood smear (Pruemer 2009). The physical examination may yield information about the type and severity of bleeding and may identify other symptoms, such as splenomegaly, that could rule out a diagnosis of ITP (Pruemer 2009). The patient’s history should include changes in prescription or nonprescription medications; vaccinations; the use of supplements, vitamins, or herbs; exposure to pesticides, herbicides, or other chemicals; a diagnosis of lymphoma, lupus, HCV, or HIV; insect or animal bites; travel outside the US; a family history of autoimmune diseases; a family or personal history of bruising easily or of a bleeding disorder; and a personal history of numerous colds, flu, or infections (PDSA 2011a).

Effects of Chronic ITP on Health Outcomes and Quality of Life

In 2009, the Platelet Disorder Support Association surveyed 251 members, including patients with acute and chronic ITP (PDSA 2011c). Sixty percent of respondents indicated that ITP had negative effects on their ability to exercise or to engage in sports; 54% reported mood changes; 44% noted that ITP interfered with their ability to travel; and 31% to 36% indicated that the condition affected their ability to take care of children/family members, to engage in social activities, to perform household tasks, and to perform their job responsibilities. Respondents reported fatigue (67%), bruising (63%), anxiety/fear (57%), and bleeding gums (29%). Almost half (44%) indicated that they worried about the future, and 31% were discouraged by the treatment options that were available to them.

An online survey of patients diagnosed with ITP and healthy, age- and gender-matched controls was conducted to determine the impact of ITP on health-related QOL, utilization of health care resources, and workplace productivity (Snyder 2008, Tarantino 2010). A total of 1,002 patients with ITP and 1,031 controls completed the survey, which included a comprehensive health-related QOL assessment. Patients with ITP had significantly lower scores on 7 of 8 health-related QOL domains, which included physical function, bodily pain, and general health, as well as lower scores on the physical and mental summary measures compared with controls (P<.05 for all comparisons) (Snyder 2008). Patients who had been diagnosed with ITP within the past 5 years had significantly (P=.019) lower overall QOL scores compared with patients who had been diagnosed more than 5 years before the survey. Lower platelet counts were consistently associated with worse scores on an ITP-Patient Assessment Questionnaire. This study demonstrated that patients with ITP have significant deficits in their health-related QOL (Snyder 2008).

With respect to health care utilization, a significantly higher proportion of patients with ITP reported visits to their primary care physicians (20%) or to specialists (28%) within the month preceding the survey, whereas only 11% of the healthy controls reported visits to primary care providers or specialists during the same period (P≤.001) (Tarantino 2010). More than half (56%) of the patients with ITP had taken sick leave compared with 30% of the controls (P≤.001), and the ITP patients were more likely to report an inability to perform usual chores (18% and 13% for patients and controls, respectively; P≤.003). Patients with ITP scored significantly worse than the healthy controls on 6 work productivity measures (P≤.05) (Tarantino 2010).

Current Treatment Options

PRIMARY IMMUNODEFICIENCY

Treatment priorities for patients with PIDDs focus on preventing infections, increasing the patient’s life expectancy, and improving QOL (Lindegren 2004). Several therapeutic approaches are available for patients with PIDD, including treatment of infections with antibiotics; immunoglobulin replacement therapy with IgG; and potentially curative treatments, including gene therapy and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) (Durandy 2005, Lindegren 2004, Notarangelo 2006).

Antibiotics play an essential role in the treatment of infections and also contribute to prophylactic management of infectious diseases, such as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (Lindegren 2004). Patients with antibody-deficient PIDDs are at increased risk of infections with encapsulated bacteria, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis. Timely treatment with antibiotics prevents progression of these infections to meningitis, osteomyelitis, consolidated pneumonitis, and mastoiditis (Durandy 2005). However, treatment with antibiotics cannot address all of the types of infections that commonly occur in patients with PIDD. For example, the microorganisms commonly responsible for mycoplasma infections are resistant to most antibiotics, although they are somewhat sensitive to tetracyclines and floxacins (Durandy 205).

IgG replacement therapy in patients with PIDDs is complex, requiring an individualized patient approach for the most appropriate and effective dosage, frequency of infusions, route of administration, and monitoring to ensure optimal patient outcomes (Maarschalk-Ellerbroek 2011, Shehata 2010). Despite these challenges, the efficacy of IgG as replacement or immunomodulatory therapy for PIDDs is well established (Cherin 2010). IgG replacement therapy may be administered via IV infusions or SC injections and is viewed as the primary treatment for PIDDs (Durandy 2005, Lindegren 2004, Orange 2006). Early diagnosis and appropriate management with IgG replacement therapy reduces morbidity and mortality and improves QOL in patients with PIDDs (Shehata 2010). Studies have shown that IgG replacement therapy can decrease infection rates and hospitalizations. Evidence also suggests that IgG replacement therapy may reduce the risk of comorbid chronic illnesses that often affect patients with PIDDs (Shehata 2010).

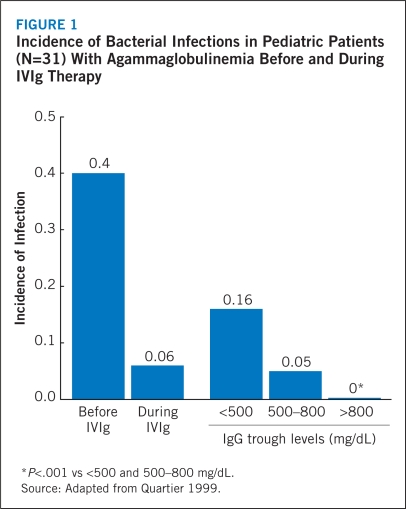

Although no randomized, controlled studies have been conducted, 500 mg/dL has been viewed as a minimum acceptable target for IgG trough serum levels. Increased doses of IgG and subsequent elevations in trough serum levels have been associated with fewer infections and shorter illnesses (Maarschalk-Ellerbroek 2011). It is recommended that IgG trough serum levels range from 600 to 900 mg/dL (Orange 2010). In a study of pediatric patients with agammaglobulinemia, the annual incidence of bacterial infections was lowest when IgG trough serum levels were maintained at >800 mg/dL (Figure 1) (Quartier 1999). A recent meta-analysis of 17 studies involving 676 patients with PIDDs found that IgG trough serum levels increased by 121 mg/dL with each additional 100-mg/kg increase in the IVIg dose (Orange 2010). The incidence of pneumonia progressively declined as IgG trough serum levels increased; pneumonia incidence showed a significant 27% reduction with each 100-mg/dL increase in trough IgG (Orange 2010). These results appear to support the clinical utility of higher IgG trough serum levels (Orange 2010). However, investigators continue to recognize that the IgG replacement dose must be individualized to achieve the best clinical response and long-term outcomes (Lucas 2010, Maarschalk-Ellerbroek 2011). For example, Lucas and colleagues demonstrated that the IgG trough serum level and the dose of replacement therapy required to maintain a minimal infectious burden are unique to each individual patient (Lucas 2010). Protective IgG trough serum levels were achieved with a broad range of replacement doses (0.2–1.2 g/kg/mo), supporting the individualization of doses. Of note, patients with bronchiectasis required twice as much replacement therapy to achieve the same IgG level compared with those free of bronchiectasis. The authors concluded that the goal of IgG replacement therapy should be to improve individualized clinical outcomes rather than to achieve a specific trough serum level.

FIGURE 1.

Incidence of Bacterial Infections in Pediatric Patients (N=31) With Agammaglobulinemia Before and During IVIg Therapy

*P<.001 vs <500 and 500–800 mg/dL.

Source: Adapted from Quartier 1999.

Because there are significant differences in the half-life of IgG among patients with PIDD, the frequency and amount of immunoglobulin therapy may vary from patient to patient. The proper amount may be determined by monitoring clinical response. The dosage should be adjusted over time to achieve the desired IgG trough serum levels and clinical responses. No randomized, controlled trial data are available to determine an optimal trough level in patients receiving immunoglobulin therapy (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

In patients with SCID, allogeneic HSCT has been the definitive treatment for nearly 40 years (Notarangelo 2006). HSCT is also used for the treatment of patients with other types of PIDD. However, patients are at increased risk of life-threatening complications, including GVHD, after undergoing this procedure (Notarangelo 2006). A number of challenges remain before HSCT may be considered standard therapy for patients with PIDDs; these challenges include improving the critical care required by HSCT patients; providing more accurate identification of potential stem-cell donors; developing strategies to prevent or control GVHD; and applying interventions that will improve thymopoiesis (Notarangelo 2006).

CHRONIC IMMUNE THROMBOCYTOPENIC PURPURA

The main treatment goal for both children and adults with ITP is to ensure adequate hemostasis rather than to achieve a “normal” platelet count (Neunert 2011). Children with no bleeding or mild bleeding may require only observation regardless of the platelet count, whereas treatment with a short-term course of corticosteroids may be administered to children with platelet counts below 10 × 109/L or to those experiencing mucosal bleeding; long-term corticosteroid treatment is not recommended in children because of the risk of side effects (Cines 2002, Neunert 2011). First-line treatment of children with ITP may also include a single dose of IVIg (0.8 to 1.0 g/kg) (Cines 2002, Neunert 2011). Second-line treatments for children with ITP who are nonresponders or who have chronic disease include rituximab, high-dose dexamethasone, and splenectomy (Cines 2002, Neunert 2011).

The optimal treatment of adults with chronic ITP is based on the individual patient’s risk of bleeding, on the side effects associated with treatment, and on the patient’s treatment preferences (Neunert 2011). Pharmacologic therapy is recommended for newly diagnosed adults with platelet counts below 30 × 109/L (Neunert 2011). Pharmacologic options for these patients include treatment with IVIg, corticosteroids, or anti-D immunoglobulin (Cines 2002, Neunert 2011, NHLBI 2011). Adults with refractory ITP after first-line corticosteroid therapy are candidates for splenectomy. Thrombopoietin-receptor agonists are recommended for patients who are at increased risk of bleeding, who relapse after splenectomy, or who have contraindications to splenectomy and have failed to respond to at least 1 other therapy (Neunert 2011). Rituximab has also been used (Neunert 2011). Emergency treatments to increase platelet counts in adults with ITP include IVIg, corticosteroids, platelet transfusions, recombinant factor VIIa, antifibrinolytics, and emergent splenectomy (Neunert 2011).

ROUTES OF ADMINISTRATION

Today, the majority of patients with PIDD receive IgG via IV or SC injection. Each route of administration has both benefits and limitations and must be tailored to the individual patient’s needs and lifestyle (Durandy 2005).

Self-administered SC injections of IgG are more convenient for some patients, are associated with a low rate of systemic AEs, and provide stable IgG trough serum levels. The SC route is particularly useful for patients with venous access problems (Durandy 2005).

Table 6 lists the key features of IVIg. Since IV injections of IgG are administered by health care providers, regular follow-up helps to ensure continuity of care and comprehensive disease management (Durandy 2005).

TABLE 6.

Key Features of IVIg

| Features | Description |

|---|---|

| Pharmacokinetics | High “peak” IgG level immediately after infusion, followed by relatively low level at “trough” just before next dose is due |

| FDA-approved indications | Current indications include use as replacement therapy in patients with primary immunodeficiency syndromes, ITP, CLL, KD, pediatric HIV, and CIDP |

| Systemic side effects | Common |

| Local reactions | Infrequent |

| Administration | Typically administered in outpatient clinic or home setting with nursing support |

| Average length of infusion | 2 to 4 hours |

| Dosing interval | Usually once every 3 or 4 weeks |

| Most common adverse events | Headache, chills, low-grade fever, myalgia, nausea |

| Patient satisfaction | A better option than SCIg for patients who have difficulty with needles and/or self-injection. Preferable in patients who have difficulty with compliance. |

CIDP = chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; CLL = chronic lymphocytic leukemia; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IgG = immunoglobulin G; ITP = immune thrombocytopenic purpura; IVIg = intravenous immunoglobulin; KD = Kawasaki disease; SCIg = subcutaneous immunoglobulin.

Privigen® is FDA-approved for PIDD and chronic ITP.

Sources: Adapted from Blaese 2007, Skoda-Smith 2010, Cherin 2010.

In the 2007 IDF survey of PIDDs in the US, 74% of respondents indicated that they were currently receiving treatment for their disease (IDF 2009a). Of these patients, 58% were receiving IVIg therapy, and 16% were being treated with SC injections. In comparison, in the 2008 IDF treatment survey, 69% and 23% of patients were receiving IV and SC injections, respectively (IDF 2009b).

In patients with PIDDs, standard doses of IVIg range from 300 to 600 mg/kg body weight, administered at 3- to 4-week intervals, although some patients may require more frequent infusions to achieve optimal clinical results (Orange 2011a). For patients with autoimmune diseases, such as chronic ITP, the recommended dose of IVIg is 2 g/kg (Maddur 2009). A typical treatment regimen consists of 5 daily infusions of 400 mg/kg each or a single dose of 2 g/kg, followed by additional infusions of 2 g/kg at intervals of 4 to 6 weeks (Maddur 2009, Negi 2007). The mean half-life of infused IVIg is approximately 25 to 32 days (Maarschalk-Ellerbroek 2011). Patients must be evaluated individually, as the outcomes desired with a specific IgG regimen can differ from patient to patient (Orange 2011a).

Once the decision has been made to use an IVIg product, numerous payer-directed barriers may impede a physician’s efforts to provide optimal therapy in PIDD (Table 7) (Orange 2011b). For example, some payers require trough-level monitoring every 3 months. While trough levels can be helpful in guiding treatment in some patients, frequent monitoring may unnecessarily add to costs. Another potential barrier is frequent requests from payers for a trial of therapy cessation. In a genetically based disorder such as PIDD, the underlying reason for requiring IVIg will not change, and patients will require treatment for the remainder of their lives. A trial of IVIg cessation is not an option in these individuals (Orange 2011b).

TABLE 7.

Potential Payer-directed Barriers to Applying Best Practice in PIDD

|

Source: Orange 2011b. Reproduced with permission.

Guiding principles for the optimal use of IVIg products are listed in Table 8.

TABLE 8.

Eight Guiding Principles for the Use of IVIg Products in PIDD

|

IVIg = intravenous immunoglobulin; SCIg = subcutaneous immunoglobulin.

Source: Orange 2011b. Reproduced with permission.

When choosing the most appropriate IVIg product, physicians should compare the risks and benefits of the available preparations, based on product attributes, as well as the health status of the individual patient. Patients with no known risk factors for serious AEs are likely to respond well to a high-concentration IVIg formulation. However, all patients should be started at the minimum infusion rate and titrated per individual tolerability. Patients known to be at risk of renal failure should not be given IVIg formulations with a high sugar and/or sodium content and high osmolality/osmolarity. Moreover, IVIg products should be administered at the lowest dose and at the slowest possible infusion rate in these patients (Cherin 2010). Similarly, IVIg products with a high sugar and/or sodium content and high osmolality/osmolarity should be used with caution in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease or with an increased risk of thrombotic events. All patients should be carefully monitored during the IV infusion (Cherin 2010).

IVIg therapy is generally well-tolerated, with headache, low-grade fever, flushing, myalgia, backache, and nausea among the most commonly reported treatment-related AEs (Cherin 2010). These events are generally related to the infusion, are of mild severity, and are reversible. The per-infusion rates of mild-to-moderate AEs range from 5% to 15%, although these rates may be higher for the following patients: those with newly diagnosed hypogammaglobulinemia that has never been treated with IVIg; those who are switching from one IVIg product to another; those who have had a dose interruption; and those with a chronic underlying infection, such as bronchitis or sinusitis (Cherin 2010). The presence of aggregates in the IVIg formulation and rapid infusion rates (>0.08 mL/kg/min) are associated with an increased risk of infusion reactions (Cherin 2010). The risk of AEs may be reduced by eliminating aggregates, by administering the product at a slower infusion rate, and by premedicating the patient with corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or antipyretics (Cherin 2010). Serious AEs have been rarely reported during post-marketing surveillance of IVIg products. These events have included acute renal failure, stroke, myocardial infarction, venous thromboembolism, anaphylaxis, aseptic meningitis, and hemolysis (Cherin 2010).

All IVIg products have a boxed warning regarding the potential for renal failure (FDA 1998). The use of IVIg products, particularly those containing sucrose, has been reported to be associated with a disproportionate occurrence of renal dysfunction, acute renal failure, osmotic nephropathy, and death. Patients at risk of acute renal failure include those with any degree of pre-existing renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, advanced age (>65 years), volume depletion, sepsis, or paraproteinemia, or those receiving known nephrotoxic drugs. Privigen® does not contain sucrose or any other sugars in its formulation (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

DIFFERENCES IN INTRAVENOUS IMMUNOGLOBULIN PREPARATIONS

IVIg products are derived from pooled plasma donated by a large number of healthy donors (15,000 to 60,000) to ensure that the products contain a wide spectrum of antibodies (Cherin 2010, Fernandez-Cruz 2009, Orange 2006). All IVIg preparations must adhere to national and international standards to ensure viral safety as well as to achieve optimal therapeutic efficacy and tolerability (Cherin 2010).

The manufacture of IVIg products generally involves the purification of pooled donor plasma using fractionation and chromatography (Cherin 2010). The resulting IVIg products differ in composition, and these variations may affect their tolerability (Cherin 2010). The currently available IVIg products may vary with respect to:

Product formulation. Whether the product is lyophilized or liquid (ready-to-use) has implications for convenience in terms of storage, the time required for reconstitution (lyophilized products), patient administration time, the potential for errors, and transport (Siegel 2005).

Available concentration of IgG. Protein concentrations range from 3% to 12% in the various IVIg products. A product’s concentration affects its administration volume (Siegel 2005).

Type of stabilizer used. Stabilizers include glycine, proline, and sugars (e.g., glucose, maltose, sucrose, or sorbitol) (Cherin 2010). All are used to keep the IgG molecule in its monomeric form. An increased risk of renal dysfunction has been associated with IVIg formulations that contain sucrose (Siegel 2005).

Maximum recommended infusion rate. This determines the amount of time required to complete an infusion and the potential for AEs, and it can have a significant effect on patient convenience and overall experience (Siegel 2005).

Osmolality. This may increase considerably when lyophilized products are reconstituted for administration (Siegel 2005).

Sugar content. This increases the risk of AEs in patients with diabetes. Higher rates of renal dysfunction and acute renal failure have been associated with products that use sucrose as a stabilizer (Siegel 2005).

Sodium content. This may be higher when lyophilized products are reconstituted for administration and may increase certain patients’ risk of renal and cardiac events (Siegel 2005). Sodium content is also an important consideration in patients with fluid restrictions.

pH levels. These are important determinants of product stability. A pH level of approximately 4.5 is associated with greater purity and maximal monomer content. The addition of stabilizers to maintain pH levels may increase the risk of several AEs, including renal toxicity (Siegel 2005). pH is an important consideration in neonates and infants.

IgA content. This increases the risk of anaphylactic shock in patients with antibodies to IgA and a history of hypersensitivity reactions (Siegel 2005).

Volume load. This affects the amount of product that must be given. The administration of large-volume infusions may not be well-tolerated by patients with heart failure, renal dysfunction, hypertension, or vascular disease (Siegel 2005).

Product Information

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Privigen® is an immune globulin intravenous (human), 10% liquid indicated for the treatment of the following conditions:

Primary humoral immunodeficiency. Privigen® is indicated as replacement therapy for primary humoral immunodeficiency. This includes, but is not limited to, the humoral immune defect in congenital agammaglobulinemia, common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), X-linked agammaglobulinemia, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and severe combined immunodeficiencies (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura.Privigen® is indicated for the treatment of patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) to raise platelet counts (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

DESCRIPTION

Privigen® is a ready-to-use, sterile, 10% protein liquid preparation of polyvalent human immunoglobulin G (IgG) for intravenous administration. Privigen® has a purity of at least 98% IgG, consisting primarily of monomers. The balance consists of IgG dimers (≤12%), small amounts of fragments and polymers, and albumin. Privigen® contains ≤25 mcg/mL IgA. The IgG subclass distribution (approximate mean values) is IgG1, 67.8%; IgG2, 28.7%; IgG3, 2.3%; and IgG4, 1.2%. Privigen® has an osmolality of approximately 320 mOsmol/kg (range: 240 to 440) and a pH of 4.8 (range: 4.6 to 5.0) (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

IgG isolated from the pooled plasma of a large number of donors may form idiotype/anti-idiotype antibody dimers. In turn, the presence of IgG dimers in IVIg may be associated with an increased risk of adverse reactions, such as headache, fever, and flushing, during IV infusion of IgG (Berger 2011, Bolli 2010). Dimer levels in IVIg products may be controlled by formulating the product at a low pH and/or by adding small amphiphilic molecules as stabilizers (Berger 2011, Bolli 2010). The hydrophobic groups in these compounds may interact with the hydrophobic domains of IgG molecules. This inhibits the occurrence of hydrophobic interactions and prevents excessive dimerization (Bolli 2010). Amphiphilic molecules are more effective for preventing protein-protein interactions compared with polar compounds or polyols, such as glycerol or sugars (Berger 2011). Masking the hydrophobic regions of the protein with amphiphilic compounds achieves stability of the IgG in the polar-water environment, decreases the likelihood of dimerization, and prevents the formation of aggregates (Berger 2011).

Studies of the effects of proline on IgG dimer and aggregate formation under various conditions (e.g., different IgG concentrations, pH, time, and temperature) have confirmed that proline is an optimal stabilizer. Proline has also been shown to prevent the fragmentation of IgG and the oxidation of proteins; such fragmentation and oxidation have the potential to decrease the activity of specific antibodies during prolonged storage (Berger 2011). Further, proline reduces the formation of idiotype/anti-idiotype dimers in liquid IVIg products (Bolli 2010). The final formulation of Privigen® contains approximately 250 mmol/L of proline (range: 210 to 290 mmol/L) as the sole stabilizer at a pH of 4.8 (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011, Berger 2011). The formulation of Privigen® with proline at a pH of 4.8 allows the product to remain stable when stored at room temperature (up to 25°C [77°F]) for 36 months (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011, Berger 2011). Of note, the administered proline is rapidly cleared from the blood circulation after an infusion of Privigen® and does not accumulate in patients with normal proline metabolism (Hagan 2011).

A 3-year study evaluated the stability and activity of Privigen® under long-term storage conditions at 25°C (Cramer 2009). Privigen® maintained good stability under these conditions. The aggregate content remained below the detection limit of 0.1% for up to 9 months in 5 of 7 lots. Increases up to 0.5% were observed by month 36, but this was still well below the specified limit of 2.0%. Fragment levels were below the detection limit of 1.9% for up to 12 months for all 7 lots. These levels increased to 3.9% by month 36. However, this was significantly less than the specification limit of 6.0%. Importantly, the purity of IgG was 98% and the monomer/dimer levels of Privigen® were 96% after 36 months of storage. Initial dimer levels ranged between 3.8% and 4.8%. These levels increased to a range of 4.9% to 7.6% after 36 months of storage, which was below the specification threshold of 12%. The function of the Fc antibody region ranged from 73% to 107% at study initiation and maintained a range of 85% to 104% after 36 months of storage. These results confirm the observation that storage of Privigen® at room temperature for up to 36 months causes minimal degradation, aggregation, or dimerization, and has no detrimental effects on Fc function and on the activity of specific antibodies (Bolli 2010, Berger 2011).

Privigen® does not contain sucrose or other forms of carbohydrate stabilizers. IVIg products that contain sucrose as a stabilizer have been associated with renal dysfunction. Only trace amounts of sodium are present in Privigen®. Privigen® contains no preservatives and does not require refrigeration or reconstitution prior to administration (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

MANUFACTURING PROCESS

Privigen® is prepared from large pools of human plasma by a combination of cold ethanol fractionation, octanoic acid fractionation, and anion exchange chromatography. The IgG proteins are not subjected to heating or to chemical or enzymatic modification. The Fc and Fab functions of the IgG molecule are retained. Fab functions tested include antigen binding capacities, and Fc functions tested include complement activation and Fc-receptor-mediated leukocyte activation (determined with complexed IgG). Privigen® does not activate the complement system or prekallikrein in an unspecific manner (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

All plasma units used in the manufacture of Privigen® have been tested and approved for manufacture using FDA-licensed serologic assays for hepatitis B surface antigen and antibodies to HCV and HIV-1/2 as well as FDA-licensed nucleic acid testing (NAT) for HCV and HIV-1 and have been found to be nonreactive (negative). For HBV, an investigational NAT procedure is used and the plasma units found to be negative; however, the significance of a negative result has not been established. In addition, the plasma has been tested for B19V DNA by NAT. Only plasma that passed virus screening is used for production, and the limit for B19V in the fractionation pool is set not to exceed 104 IU of B19V DNA per mL (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

The manufacturing process for Privigen® includes three steps to reduce the risk of virus transmission. Two of these are dedicated virus clearance steps: pH 4 incubation to inactivate enveloped viruses and virus filtration to remove, by size exclusion, both enveloped and nonenveloped viruses as small as approximately 20 nanometers. In addition, a depth filtration step contributes to the virus reduction capacity. These steps have been independently validated in a series of in vitro experiments for their capacity to inactivate and/or remove both enveloped and nonenveloped viruses (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

The viral removal, inactivation, and nanofiltration processes involved in the manufacture of Privigen® result in ≥16 log-fold reductions for HIV and West Nile virus; ≥12 log-fold reductions for large DNA viruses, such as herpes; ≥7.9 and ≥9.4 log-fold reductions for model viruses corresponding to hepatitis A and B, respectively; and ≥7.8 log-fold reductions for a model of B19V. In addition, the process used to manufacture Privigen® decreases prions that contribute to transmissible spongiform encephalopathies by at least 14.8 log-fold (Berger 2011).

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action of IVIg is complex and is not completely understood. It is thought to involve modulation of the expression and function of Fc receptors; interference with the activation of complement and the cytokine network; effects on the activation, differentiation, and effector functions of T cells and B cells; and other significant processes (Kazatchkine 2001).

Two widely studied and accepted mechanisms of IVIg action are supplementation of essential antibodies and immunomodulatory effects (Simon 2003, Kazatchkine 2001). In supplementation, IVIg therapy is used to provide protective antibodies to patients with PIDDs by delivering immune antibodies against common pathogens (Simon 2003). With immunomodulatory effects, a number of events take place (Kazatchkine 2001), including:

Blockade of Fc receptors on macrophages and effector cells

Attenuation of complement-mediated inflammatory damage

Neutralization of circulating autoantibodies by anti-idiotypes

Selective down-regulation of antibody production

Regulation of apoptosis

Mechanism of action in primary immunodeficiency diseases. Privigen® is a replacement therapy for PI, and supplies a broad spectrum of opsonic and neutralizing IgG antibodies against bacterial, viral, parasitic, and mycoplasma agents and their toxins (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011). As recommended by the FDA and by the Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association, Privigen® is manufactured from the pooled plasma of thousands of blood donors and therefore includes a broad variety of antibody specificities against common pathogens to which the donor population has been exposed (Cramer 2009, Orange 2006). Moreover, the antibodies in Privigen® are structurally and functionally intact, and their effector functions are fully operative (Cramer 2009). The mechanism of action of Privigen® in PI has not been fully elucidated (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Mechanism of action in immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Studies have suggested that IVIg mediates short-term increases in platelet counts as a result of reticuloendothelial system (RES) blockade, which may occur via two independent mechanisms: 1) IVIg contains IgG dimers and multimers that can bind to Fc receptors and block platelet clearance and prolong platelet survival, and 2) IVIg contains IgG molecules that bind to host antigens, form immune complexes, and compete with antibody-sensitized platelets for Fc receptors in the RES, resulting in prolonged platelet survival (Lazarus 1998). Other mechanisms may also contribute to the inhibition of thrombocytopenia. For example, IVIg has been shown to have effects on the cellular immune response itself. Specifically, IVIg-induced changes in cellular immunity may modulate B- and T-cell functions, leading to the suppression of autoantibody production (Lazarus 1998). The mechanism of action of high doses of immunoglobulins in the treatment of chronic ITP has not been fully elucidated (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics

Treatment of primary humoral immunodeficiency. In the pivotal clinical study of Privigen®, which assessed the product’s efficacy and safety in 80 subjects with PI, serum concentrations of total IgG and IgG subclasses were measured in 25 subjects (ages 13 to 69 years) following the 7th infusion for 3 subjects on a 3-week dosing interval and following the 5th infusion for 22 subjects on a 4-week dosing interval. The doses of Privigen® used in these subjects ranged from 200.0 mg/kg to 714.3 mg/kg. After the infusion, blood samples were taken until Day 21 and Day 28 for the 3-week and 4-week dosing intervals, respectively. Table 9 summarizes the pharmacokinetic parameters of Privigen®, based on serum concentrations of total IgG (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

TABLE 9.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Privigen® in Subjects With PI

| 3-Week Dosing Interval (n=3) | 4-Week Dosing Interval (n=22) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (Range) | Mean (SD) | Median (Range) | |

| Cmax (peak, mg/dL) | 2,550 (400) | 2,340 (2,290–3,010) | 2,260 (530) | 2,340 (1,040–3,460) |

| Cmin (trough, mg/dL) | 1,230 (230) | 1,200 (1,020–1,470) | 1,000 (200) | 1,000 (580–1,360) |

| t1/2 (days) | 27.6 (5.9) | 27.8 (21.6–33.4) | 45.4 (18.5) | 37.3 (20.6–96.6) |

| AUC0–t (day × mg/dL)* | 32,820 (6,260) | 29,860 (28,580–40,010) | 36,390 (5,950) | 36,670 (19,680–44,340) |

| AUC0–∞ (day × mg/dL)* | 79,315 (20,170) | 78,748 (59,435–99,762) | 104,627 (33,581) | 98,521 (64,803–178,600) |

| Clearance (mL/day/kg) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.9–2.1) |

| Mean residence time (days)* | 38.6 (8.1) | 39.5 (30.1–46.2) | 65.2 (24.7) | 59.0 (33.2–129.6) |

| Volume of distribution at steady state (mL/kg)* | 50 (13) | 44 (40–65) | 84 (35) | 87 (40–207) |

Cmax = maximum (peak) serum concentration; Cmin = minimum (trough) serum concentration; t½ = elimination half-life; AUC0-t = area under the curve from 0 hour to last sampling time; AUC0-∞ = area under the curve from 0 hour to infinite time.

Calculated by log-linear trapezoidal rule.

The median half-life of Privigen® was 36.6 days for the 25 subjects in the pharmacokinetic subgroup (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Although no systematic study was conducted to evaluate the effect of gender and age on the pharmacokinetics of Privigen®, based on a small sample size (11 males and 14 females) it appears that clearance of Privigen® is comparable in males (1.27 ± 0.35 mL/day/kg) and females (1.34 ± 0.22 mL/day/kg). In 6 subjects between 13 and 15 years of age, the clearance of Privigen® (1.35 ± 0.44 mL/day/kg) was comparable with that observed in 19 adult subjects 19 years of age or older (1.29 ± 0.22 mL/day/kg) (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

The IgG subclass levels observed in the pharmacokinetic study were consistent with a physiologic distribution pattern (mean trough values): IgG1, 564.91 mg/dL; IgG2, 394.15 mg/dL; IgG3, 30.16 mg/dL; and IgG4, 10.88 mg/dL (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Treatment of chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Pharmacokinetic studies with Privigen® were not performed in subjects with chronic ITP (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

Preparation and Handling

Privigen® is a clear or slightly opalescent, colorless to pale yellow solution. Inspect parenteral drug products visually for particulate matter and discoloration prior to administration, whenever solution and container permit. Do not use if the solution is cloudy or turbid, or if it contains particulate matter (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Do not shake.

Do not freeze. Do not use if Privigen® has been frozen.

Privigen® should be at room temperature (up to 25°C [77°F]) at the time of administration.

Do not use Privigen® beyond the expiration date on the product label.

The Privigen® vial is for single-use only. Promptly use any vial that has been entered. Privigen® contains no preservative. Discard partially used vials or unused product in accordance with local requirements.

Infuse Privigen® using a separate infusion line. Prior to use, the infusion line may be flushed with Dextrose Injection, USP (D5W) or 0.9% Sodium Chloride for Injection, USP.

Do not mix Privigen® with other IVIg products or other IV medications. Privigen® may be diluted with Dextrose Injection, USP (D5W).

An infusion pump may be used to control the rate of administration.

If large doses of Privigen® are to be administered, several vials may be pooled using aseptic technique. Begin infusion within 8 hours of pooling.

Dosage

Treatment of primary humoral immunodeficiency. Because there are significant differences in the half-life of IgG among patients with PI, the frequency and amount of immunoglobulin therapy may vary from patient to patient. The proper amount can be determined by monitoring clinical response (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

The recommended dosage of Privigen® for patients with PI is 200 to 800 mg/kg (2 to 8 mL/kg) administered every 3 to 4 weeks. If a patient misses a dose, the missed dose should be administered as soon as possible, and then scheduled treatments should be resumed every 3 or 4 weeks, as applicable (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

The dosage should be adjusted over time to achieve the desired trough serum levels and clinical responses. No randomized controlled data are available to determine an optimal trough level in patients receiving immune globulin therapy (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Treatment of chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. The recommended dosage of Privigen® for patients with chronic ITP is 1 g/kg (10 mL/kg) administered daily for 2 consecutive days, resulting in a total dose of 2 g/kg. The high-dose regimen (2 g/kg divided over 2 days) is not recommended for individuals with expanded fluid volumes or where fluid volume may be a concern (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Administration

Privigen® is for intravenous administration only. Monitor the patient’s vital signs throughout the infusion. Slow or stop the infusion if adverse reactions occur. If symptoms subside promptly, the infusion may be resumed at a lower rate that is comfortable for the patient (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Ensure that patients with pre-existing renal insufficiency are not volume depleted. For patients judged to be at risk of renal dysfunction or thrombotic events, administer Privigen® at the minimum infusion rate practicable, and discontinue Privigen® administration if renal function deteriorates. Table 10 provides the recommended infusion rates for Privigen® (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

TABLE 10.

Recommended Infusion Rates for Privigen®

| Condition | Initial Infusion Rate | Maintenance Infusion Rate (If Tolerated) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD) | 0.5 mg/kg/min (0.005 mL/kg/min) | Increase to 8 mg/kg/min (0.08 mL/kg/min) |

| Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) | 0.5 mg/kg/min (0.005 mL/kg/min) | Increase to 4 mg/kg/min (0.04 mL/kg/min) |

Source: Adapted from Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011.

The following patients may be at risk of developing inflammatory reactions on rapid infusion of Privigen® (>4 mg/kg/min [0.04 mL/kg/min]): 1) those who have never received Privigen® or another IgG product or have not received it within the past 8 weeks, and 2) those who are switching from another IgG product. These patients should be started at a slow rate of infusion (e.g., 0.5 mg/kg/min [0.005 mL/kg/min] or less) and gradually advanced to the maximum rate, as tolerated (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

How Supplied

Privigen® is supplied in a single-use, tamper-evident vial containing the labeled amount of functionally active IgG. The components used in the packaging for Privigen® are latex-free (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011). The following presentations of Privigen® are available:

| NDC Number | Fill Size (mL) | Grams Protein |

|---|---|---|

| 44206-436-05 | 50 | 5 |

| 44206-437-10 | 100 | 10 |

| 44206-438-20 | 200 | 20 |

Each vial has an integral suspension band and a label with two peel-off strips showing the product name, lot number, and expiration date (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Storage and Handling

When stored at room temperature (up to 25°C [77°F]), Privigen® is stable for up to 36 months, as indicated by the expiration date printed on the outer carton and on the vial label (Privigen® Prescribing Information 2011).

Keep Privigen® in its original carton to protect it from light.

Do not freeze.

Clinical Trials

TREATMENT OF PRIMARY IMMUNODEFICIENCY

Safety and Efficacy of Privigen®, a Novel 10% Liquid Immunoglobulin Preparation for Intravenous Use, in Patients With Primary Immunodeficiencies

Methods. A phase III, open-label, single-arm, multicenter trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of Privigen® in 80 patients with PIDD (59 with CVID and 21 with XLA) (Stein 2009). The patients’ median age was 25 years (range: 3–69 years). All patients received Privigen® at 3- to 4-week intervals for 12 months. Doses ranged from 200 to 800 mg/kg.

The study’s primary end point was the number of acute serious bacterial infections (aSBIs), including pneumonia, bacteremia/septicemia, osteomyelitis/septic arthritis, bacterial meningitis, and visceral abscess. Secondary end points included the occurrence of any infection, the number of days missed from work or school due to illness, the number of days hospitalized, and the number of days on which antibiotics were taken.

Results. During the 12-month study period, an aSBI occurred in 6 patients (7.5%), including 3 patients with pneumonia (3.8%) and 1 patient each with septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and iatrogenic visceral abscess (following bowel perforation during surgery) (1.3% each), corresponding to an annual rate of 0.08 for the intention-to-treat population (N=80). Sixty-six patients (82.5%) experienced 255 episodes of any type of infection, including aSBIs, for an annual infection rate of 3.55 per patient. The majority of infections were mild or moderate; 16 infections (6.3%) experienced by 10 patients were considered to be severe. The most common infection was sinusitis. Table 11 lists the aSBIs and other infections that occurred during this study.

TABLE 11.

aSBIs and All Other Infections Occurring in >5% of PIDD Patients Treated With Privigen® for 12 Months

| Infections | ITT Population [N=80] No. (%) |

|---|---|

| aSBIs* | 6 (7.5) |

| Pneumonia | 3 (3.8) |

| Septic arthritis | 1 (1.3) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1 (1.3) |

| Visceral abscess | 1 (1.3) |

| All other infections | 66 (82.5) |

| Sinusitis | 25 (31.3) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 18 (22.5) |

| URTI | 15 (18.8) |

| Bronchitis | 11 (13.8) |

| Rhinitis | 11 (13.8) |

| Influenza | 10 (12.5) |

| Gastroenteritis | 7 (8.8) |

| Conjunctivitis | 6 (7.5) |

| Ear infection | 6 (7.5) |

| Urinary tract infection | 6 (7.5) |

Blood cultures were negative in 3 of the 6 patients with aSBIs and were not performed in 2 patients. In the patient with osteomyelitis, vancomycin-resistant enterococci and yeast-like fungi were found. aSBIs = acute serious bacterial infections; ITT = intention-to-treat; URTI = upper respiratory tract infection.

Source: Stein 2009. Reproduced with kind permission from Springer+Business Media: J Clin Immunol. Safety and efficacy of Privigen®, a 10% liquid immunoglobulin preparation for intravenous use, in patients with primary immunodeficiencies. 2009;29(1):137–144. Stein MR, Nelson RP, Church JA, et al. Table II.

Fifty-three patients (66.3%) missed work, school, or daycare or were unable to perform normal activities because of illness, for an annual average rate of 7.94 days per patient. Fifteen patients were hospitalized for a total of 166 days, which corresponded to an annual rate of 2.31 days of hospitalization per patient. The annual rate of antibiotic use was 87.4 days. Mean IgG trough serum levels ranged from 8.84 to 10.27 g/L for all infusions.

At least one AE occurred in 78 patients (97.5%) during the study period. Headache was the most common AE, affecting 67.5% of patients. Most AEs (60%) were mild in severity and not related to study treatment (84%). Sixteen patients (20%) experienced 38 serious AEs. Only 1 patient had serious AEs that were considered to be related to the study drug (i.e., hypersensitivity, chills, fatigue, dizziness, and body temperature increased).

Conclusions. In this pivotal phase III study, Privigen® provided stable IgG trough serum levels, a low annual aSBI rate, and a low proportion of infusions with temporally associated AEs in patients requiring regular immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Tolerability of a New 10% Liquid Immunoglobulin for Intravenous Use, Privigen®, at Different Infusion Rates

Methods. Patients who completed the pivotal phase III trial of Privigen®, described above, were enrolled in a phase III, open-label, single-arm, prospective, multicenter extension study for further treatment for up to 124 weeks at stable doses (up to 875 mg/kg) (Sleasman 2010). Forty-five patients with PIDD (34 with CVID and 11 with XLA) participated in the study. The patients’ median age was 19 years (range: 4–66 years).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate further the safety and efficacy of Privigen® in patients with PIDD and to assess the tolerability of Privigen® at a higher maximum infusion rate (12 mg/kg/min). The study’s primary tolerability end point was the frequency of temporally associated AEs, which were defined as any AE that occurred during an infusion or within 72 hours after completion of an infusion, regardless of assessment of causal relation to the study drug. AEs were continuously monitored at each study visit and with patient diaries.

All of the patients received infusions of Privigen® at 3- to 4-week intervals. Treatment lasted for up to 124 weeks, with all doses of study medication remaining at the same level (not exceeding 875 mg/kg) unless a dose adjustment was required for medical reasons. At the investigators’ discretion (based on the patients’ tolerability), 23 patients were selected to receive a high maximum infusion rate (HIR; 12 mg/kg/min), and the remaining 22 patients received a low maximum infusion rate (LIR; 8 mg/kg/min).

Results. Privigen® was well tolerated at the high infusion rate without any compromise in tolerability. The percentage of infusions with temporally associated AEs was significantly lower in the HIR group compared with the LIR group (8% vs 21%, respectively; P=.0089). Moreover, the most frequently associated AEs were less common in patients receiving HIR than in those receiving LIR (Table 12). Overall, headache was the most common temporally associated AE, occurring in 56 (8%) of 688 infusions.

TABLE 12.

Most Frequent (≥1% of Infusions in Any Group) Temporally Associated Adverse Events in PIDD Patients Treated With Privigen® for Up to 124 Weeks

| Adverse Event | Number (%*) of Temporally Associated AEs | |

|---|---|---|

| Low Max. Infusion Rate 8 mg/kg/min 423 Infusions | High Max. Infusion Rate 12 mg/kg/min 265 Infusions | |

| Headache | 54 (12.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Pain† | 23 (5.4) | 4 (1.5) |

| Nausea | 8 (1.9) | 2 (0.8) |

| Chills | 7 (1.7) | 0 (0) |

| Vomiting | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0) |

| Pyrexia | 9 (2.1) | 1 (0.4) |

Percentage of infusions associated with each AE (i.e., number of AEs divided by number of infusions).

Includes the following AE preferred terms: pain, abdominal pain, abdominal pain lower, abdominal pain upper, back pain, chest pain, infusion site pain, injection site pain, neck pain, pain in extremity, urinary tract pain, pharyngolaryngeal pain, and ear pain.

Source: Adapted from Sleasman 2010.

Conclusions. The results of this study demonstrate that patients can tolerate Privigen® at high infusion rates without compromising tolerability.

Efficacy and Safety of Privigen® in Children and Adolescents With Primary Immunodeficiency

Methods. A phase III, prospective, open-label, multi-center, single-arm study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Privigen® in children and adolescents with CVID or XLA (Church 2009). The study population consisted of 31 pediatric patients who had participated in the pivotal phase III trial of Privigen®, described above. This population was divided into children (aged 3 to 11 years; n = 19) and adolescents (aged 12 to 15 years; n = 12). The study’s primary end point was the annual rate of aSBIs (e.g., pneumonia, bacteremia, and septicemia) per patient. Secondary end points included the annual rate of any infections per patient, the number of days missed from school or daycare, the number of days unable to perform usual activities, the number of days hospitalized, and the use of antibiotics.

All of the patients received Privigen® at doses of 200 to 800 mg/kg body weight at 3- to 4-week intervals for 12 months. The Privigen® infusions were increased to a maximum of 4 mg/kg/min for the first 3 infusions. From the fourth infusion onward, the infusion rate could be increased to a maximum of 8 mg/kg/min, if well tolerated.

Results. The annual rates of aSBIs per patient were 0.12 for children and 0.10 for adolescents. The corresponding annual rates of all infections (including aSBIs) per patient were 4.63 and 2.42, respectively. URTIs were the most common infections, occurring in 32% of all patients. The annual rates of days missed from school or daycare per patient were 11.5 in children and 4.8 in adolescents. Table 13 summarizes the study’s primary and secondary efficacy results.

TABLE 13.

Annual Rates of Efficacy Parameters in Pediatric Patients With PIDD Treated With Privigen® for 12 Months

| End Point | Children (3–11 Years) [n=19] | Adolescents (12–15 Years) [n=12] | Total [n=31] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of study days | 6,152 | 3,776 | 9,928 |

| Annual rate of aSBIs per patient | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| No. of patients with aSBI | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| No. of aSBIs | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Annual rate of all infections per patient | 4.63 | 2.42 | 3.79 |

| No. of patients with infections | 17 | 11 | 28 |

| No. of infections | 78 | 25 | 103 |

| Annual rate of days missed from school/daycare per patient | 11.51 | 4.83 | 8.97 |

| No. of patients who missed | 16 | 7 | 23 |

| No. of days missed | 194 | 50 | 244 |

| Annual rate of days hospitalized per patient | 0.53 | 0 | 0.33 |

| No. of patients hospitalized | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| No. of days hospitalized | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Annual rate of days with antibiotics per patient | 47.88 | 56.64 | 51.21 |

| No. of patients treated with antibiotics | 16 | 9 | 25 |

| No. of days on antibiotics | 807 | 586 | 1,393 |

Source: Adapted from Church 2009.

Fourteen children (74%) and 7 adolescents (58%) experienced temporally associated AEs (occurring during or within 72 hours after the end of an infusion) on at least 1 occasion. The most common temporally associated AEs were headache, fatigue, chills, and vomiting. Most of these AEs were mild or moderate in severity. The most common AEs related to Privigen® infusion were headache, vomiting, fatigue, chills, nausea, and back pain. Fourteen serious AEs occurred in 6 children, and 1 serious AE occurred in 1 adolescent. Five of the 14 serious AEs in children occurred in a single patient and were considered related to Privigen®. These events included hypersensitivity, chills, fatigue, dizziness, and increased body temperature.

Conclusions. This study demonstrated that Privigen® is effective and safe in children and adolescents with PIDD.

TREATMENT OF CHRONIC IMMUNE THROMBOCYTOPENIC PURPURA

Efficacy and Safety of Privigen®, a Novel Liquid Intravenous Immunoglobulin Formulation, in Adolescent and Adult Patients With Chronic Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Methods. A phase III, prospective, open-label study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Privigen® in 57 adolescent and adult patients with chronic ITP (Robak 2009). Patients were included in the study if they had a platelet count of ≤20 × 109/L at screening, no other known cause for thrombocytopenia, and a platelet count of ≤150 × 109/L over 6 months or a response to previous treatment with a subsequent decrease in platelet count even if the duration of chronic ITP was <6 months. The patients’ mean age was 38 years (range: 15–69 years). Fifty-two patients (91.2%) had received previous treatment for ITP.

The administration of concomitant medications, including other immunoglobulins, intravenous steroids, immunosuppressant agents, blood products, and medications that could affect the blood-clotting response, was not permitted, although oral steroids were allowed if the dose had been stable for at least 15 days prior to screening and for the duration of the study period.