Abstract

A random copolymer, poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin), consisting of N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAAm) and platinum (II) porphyrin units, behaves as an optical dual sensor for oxygen and temperature. The dual sensor is designed by incorporating an oxygen-sensitive platinum (II) porphyrin (M1) into a temperature-sensitive polymer (PNIPAAm). The polymer exhibited low critical solution temperature (LCST) property at 31.5 °C. This LCST affected the polymer’s aggregation status, which in turn affected the nanostructures, fluorescence intensities, and responses to dissolved oxygen. This enables the polymer to functionalize as a dual temperature and dissolved oxygen sensor. Oxygen response of the platinum (II) porphyrin probes in the polymer followed a two-site Stern-Volmer model, indicating the nonuniform distribution of the probes. The copolymer was used to preliminarily monitor the oxygen consumption of Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria. The results indicate a potential application of the polymer in biological fields.

Keywords: Dual optical sensor, Oxygen sensor, Temperature sensor, Platinum porphyrin, Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)

1. INTRODUCTION

Oxygen is one of the key metabolites in aerobic systems and the rate of oxygen uptake is an important indicator of cell metabolic activity which correlates to cell viability. Therefore, monitoring the oxygen consumption has caused significant scientific interests for understanding cell respiration and metabolism, as well as for other physiological and biological applications. Various types of oxygen sensors have been developed based on mechanisms such as electrochemistry [1], fluorescence quenching [2] and fluorescence-based colorimetry [3]. Because an emission quenching based sensor is non-invasive, disposable, easily miniaturized (down to sub-micrometer), and simple to process (as a coating or solid layer on optical fibers or surfaces for remote measurement of chemical and biochemical parameters), the optical approach [4] for measuring dissolved oxygen (DO) held the most interest to us among the various mechanisms being used. Furthermore, we are using the optical oxygen sensors integrated with lab-on-a-chip devices for single cell metabolism studies [5,6].

Like oxygen, temperature has a significant effect on metabolic activity of cells [7]; metabolic activity generally increases with temperature [8]. Living systems have complex metabolic networks involving many different chemical reactions which affect metabolic activities in many different ways. Therefore, it is assumed that the metabolism of cell is an overall chemical reaction (as a blackbox), the effect of temperature on the rate of chemical reaction, in general, gives a straight line slope on the Arrhenius plot that is characteristic of the particular reaction [7,9]. Recently, fluorescent temperature sensors have also attracted much attention because they allow simple monitoring of the solution temperature in terms of fluorescence intensity [10–12].

Measurement of these two parameters is often required in complex media and processes [13–18]. Recently, several kinds of dual sensors have been described for O2/T [13–18]. Almost all these sensors consist of an oxygen-sensitive probe (such as Pt(II)-5,10,15,20-tetrakis-(2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorophenyl) porphyrin (PtTFPP)) and a temperature-sensitive probe (such as Eu(III)-tris(thenoyltrifluoroacetonato)-(2-(4-diethylaminophenyl)-4,6-bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazine) (Eu(tta)3(dpbt)). Accordingly, energy transfers and other quenching interactions between the two luminescent dyes may occur [18]. Because the toxicity of europium compounds [19] has not been fully investigated, and there are no clear indications if europium is toxic compared to other heavy metals, thus their applications in the biological and medical field are restricted.

Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm) is a biocompatible polymer, displaying a thermal responsive property close to 32 °C and can be tuned to close to body temperature with an introduction of hydrophilic segments [20]. This thermoresponsive property is called low critical solution temperature (LCST) [21,22]. Usually, below the LCST, the polymer is highly swollen in water, but upon increasing the temperature above the LCST the polymer chains rapidly deswell to a collapsed polymer globule. This material is of interest due to the wide range of physical properties that are modulated by the phase transition, including the hydrophobicity, particle size, porosity, refractive index, colloidal stability, scattering cross-section, electrophoretic mobility, and rheology [23], which has been applied to diverse fields such as drug delivery [24], biosensing [25], chemical separations [26], cell culture substrates [27,28] and catalysis [29]. Some fluorophores were chemically integrated into the PNIPAAm and the fluorophore-containing polymers were studied as body temperature thermometers [30,31].

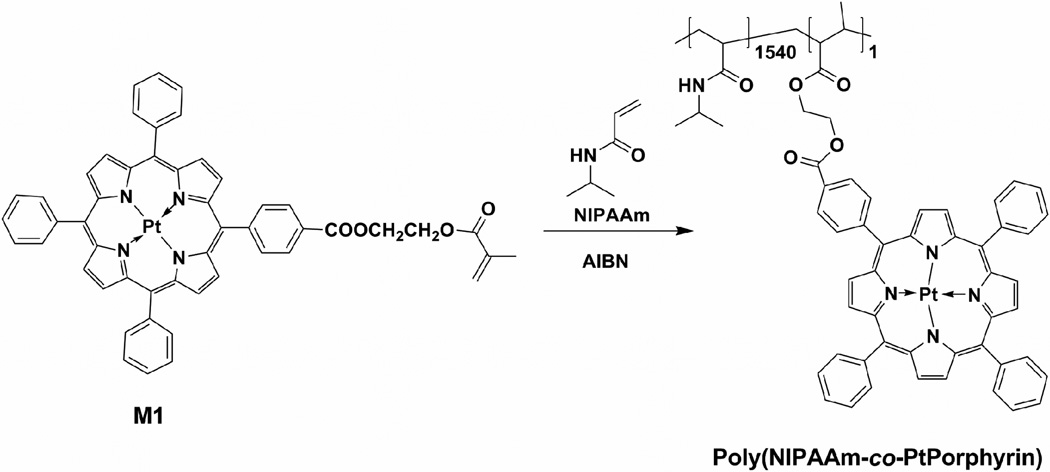

Herein, for the first time, we integrated the PNIPAAm with a platinum (II) porphyrin (oxygen probe). The oxygen probe (M1) is also a monomer, which can be polymerized with the NIPAAm monomer under nitrogen using AIBN as an initiator (Scheme 1). The fluorescence properties of the oxygen probe is expected to be stimulated or affected by the LCST property. Thus, using one probe but integrating it with a thermal-responsive PNIPAAm, the polymer will act as a dual oxygen and temperature sensor. Here we report the synthesis, the thermal response (the LCST property), the LCST stimulated nanostructures and oxygen responses. This is the first report of the synthesis and investigation of a dual oxygen and temperature sensor based on PNIPAAm. In order to demonstrate the potential application of the polymer for oxygen sensor in a biological environment, we report the preliminary results using this polymer to monitor the oxygen consumption of Escherichia coli (E. coli).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin).

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

The NIPAAm monomer was purified by recrystallization from n-hexane. Milli-Q water (18 MΩ) was used for titrations. Other chemicals and solvents were of analytical grade and were used without further purification. The oxygen sensing monomer (M1) was synthesized according to literature procedures [32]. Calibration gases (nitrogen and oxygen, each of 99.999% purity) were purchased from AIR Liquide America, LP (Houston, TX). Exact gas percentage was precisely controlled with a custom-built, in-line, digital gas flow controller. All sensing measurements were carried out at atmospheric pressure, 760 mmHg or 101.3 kPa. Luria-Bertani (LB) medium was made of 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g NaCl in 1 L distilled water.

Preparation of Poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin)

The polymer poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) was synthesized according to our previously published procedure (Scheme 1) [33]. NIPAAm (700 mg, 6.2 mmol), M1 (2.7 mg, 0.0028 mmol), and azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) (10 mg, 0.059 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL of THF. The solution was degassed by three freeze-pump-thaw cycles and stirred at 65 °C overnight under N2. The polymer was then precipitated into diethyl ether (100 mL) and filtrated. The procedure was repeated until the unreacted M1 in the diethyl ether solution disappeared completely. The precipitate obtained was dried in vacuum, affording poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) as rufous solid, 360 mg. (Yield: 51.4%). Mn = 9300, Mw/Mn = 1.61. The number ratio (x/y) of NIPAAm to PtPorphyrin units in poly(NIPAAmx-co-PtPorphyriny) was determined to be 1540:1 by comparison of absorbance (A402 nm) with monomer M1 dissolved in THF at 23 °C.

Instruments

All spectroscopic measurements were carried out with a 10-mm-path-length quartz cell. Fluorescence spectra were measured on a Shimadzu RF-5301 spectrofluorophotometer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD). Absorption spectra were measured on a UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-3600). A temperature controller was used to adjust the temperature from 25 to 45 °C using a Fisher Scientific Isotemp 202S water bath with ± 0.5 °C precision. The measurements started after the solution was stabilized for 3 min at the designated temperature. Polymer particle sizes were measured using a 173° back-scattering Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, United Kingdom). The molecular weight of the polymer was determined by gel permeation chromatography using a Waters 1515 GPC coupled with a RI detector, in reference to a series of polystyrene standards with THF as the eluent.

Oxygen consumption by E. coli

A preculture of E. coli (strain: JM 109) was grown in 25 mL of LB medium to an optical density (OD600) of 2.0 in a 100 mL shake flask. The culture was grown at 37 °C and 200 rpm (incubator: Excella E25). Small aliquots of the stock solution of E. coli was added into the 10-mm-path-length quartz cell and then diluted to 107~108 cfu/mL calculated using OD600. OD600 in the range of 0.1 to 1 is proportional to E. coli density of 5 × 107 to 5 × 108 cfu/mL, respectively. The random copolymer was added to the cell and then 0.4 mL of mineral oil was applied to each cell. Monitoring of the fluorescent signal was initiated. Each cell was monitored for 90 min and at the same time the growth curve was recorded based on the OD600’s reading. The images were acquired on a confocal fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000E, Melville, NY). All measurements were carried out at 25 °C.

Experimental Data Processing

Data processing was performed using Origin vs 7.0 (www.originlab.com) and Matlab (www.mathworks.com) software.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Materials design and synthesis

To sense both oxygen and temperature, two indicators are usually required in a single polymer matrix [13–18]. Our design of dual functional material for sensing oxygen and temperature is to integrate the oxygen-sensitive probe (M1) with PNIPAAm possessing LCST property. Herein, the LCST property was integrated with the oxygen probe and was used to affect the fluorescence property of M1. Thus using only one fluorescence optical probe and one thermal responsive polymer, the new functional polymer is expected to act as a dual oxygen and temperature sensor. The polymer was synthesized using a typical random polymerization technique and was characterized using UV-Vis and fluorescence spectrometers to determine the content of the probe in the polymer. It was found that the ratio of probe to PNIPAAm was 1:1540 by mole.

LCST property and LCST related nanostructures

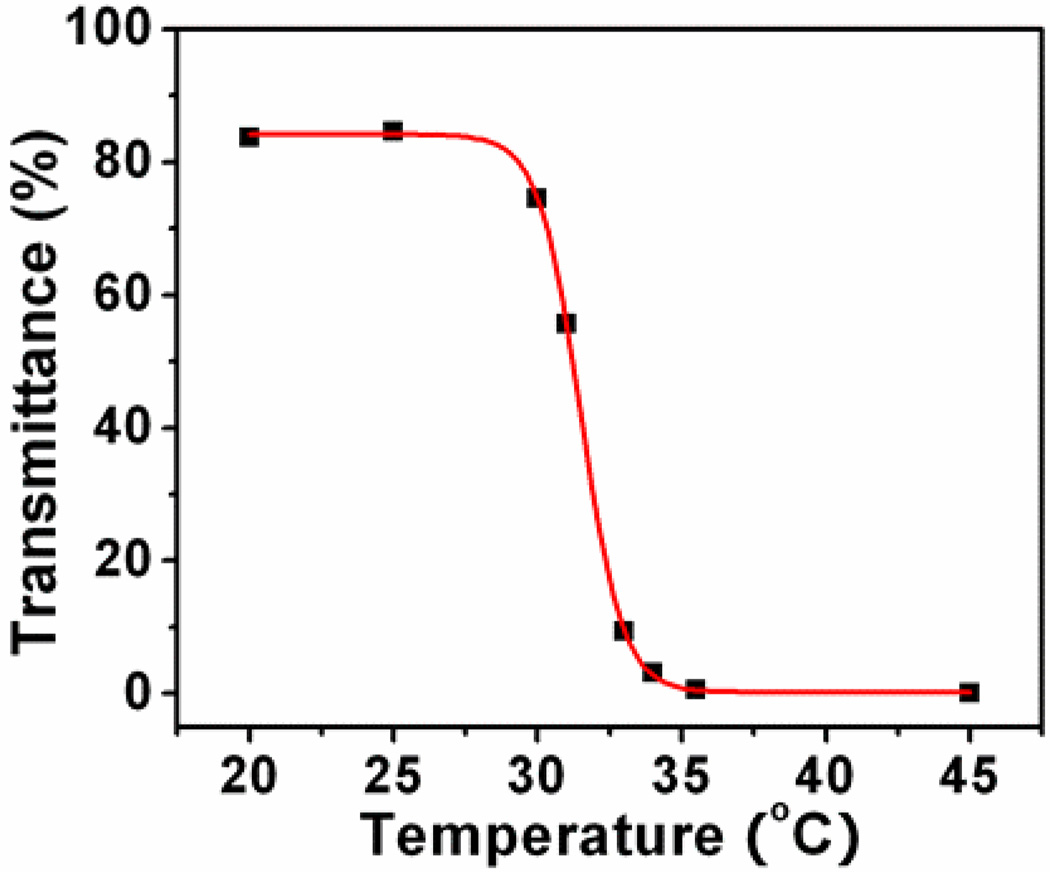

LCST property was characterized by measuring the transmittance at 650 nm on heating (Figure 1). It was found that the LCST of this polymer upon heating is 31.5 °C, which is close to the pure PNIPAAm (32°). The introduction of the hydrophobic segment of M1 did not affect the thermal property significantly. This small change, however, is most likely due to the small fraction of the hydrophobic moiety in the polymer.

Figure 1.

Temperature-dependant transmittance of the poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) solution. The sigmoidal fitting was used for LCST determination.

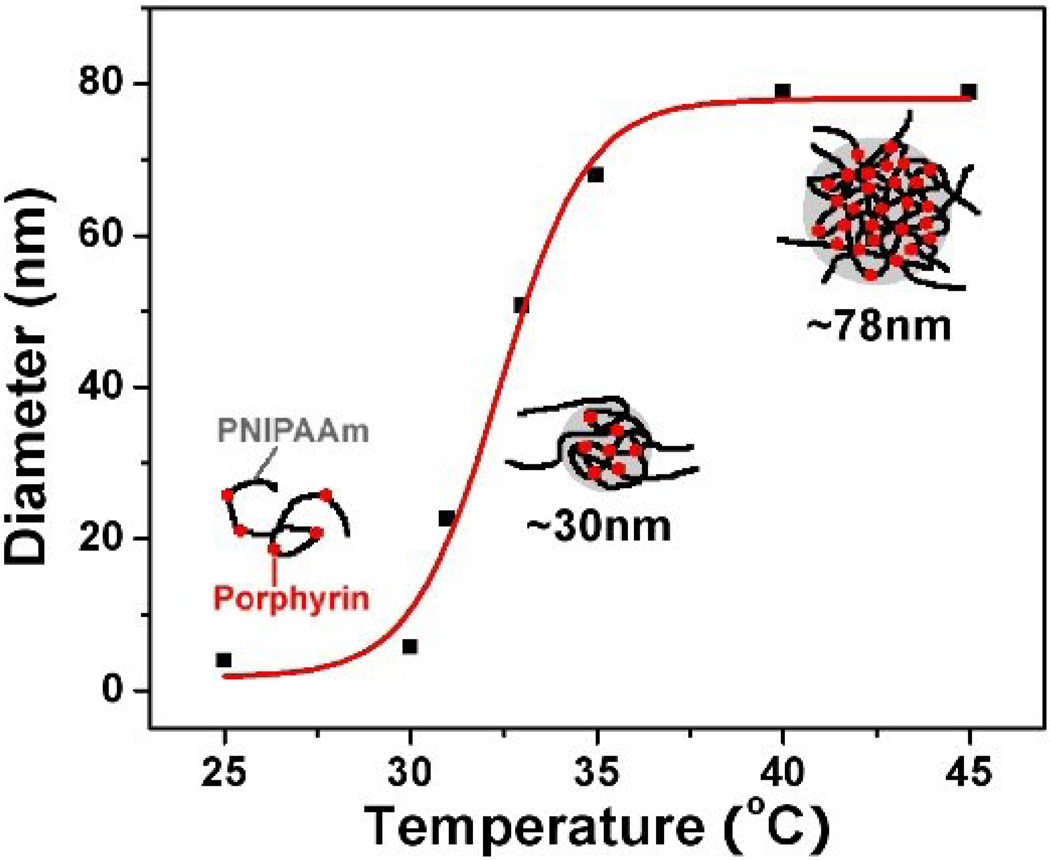

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to characterize the LCST stimulated nanostructures (Figure 2). At 25 °C, an average diameter of 4 nm was observed, showing the polymer is a unimer (Figure 2). When the temperature is over 30 °C, the diameter started to increase and stabilized at 78.8 nm when the temperature became greater than 40 °C, where the PNIPAAm becomes hydrophobic and aggregates. Figure 2 gives the schematic illustration of the nanostructure changes stimulated by the LCST. The structure change of this polymer is in accordance with those of other PNIPAAm random copolymers [30].

Figure 2.

Temperature-dependant hydrodynamic diameters of the polymer measured using dynamic laser scattering. The inserted drawings give the schematic illustrations of the nanostructure changes stimulated by the LCST.

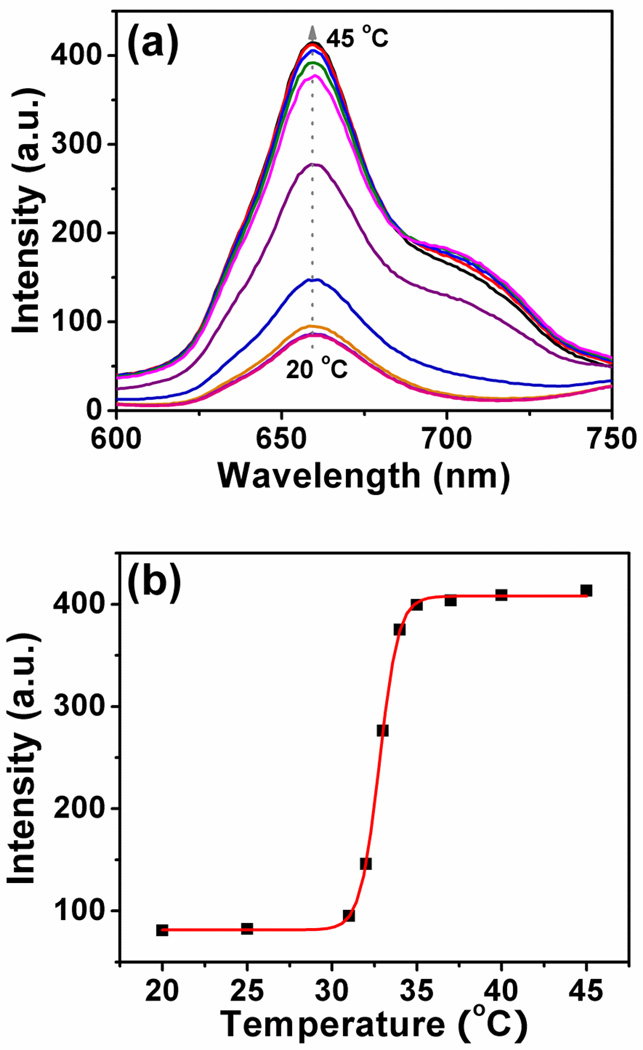

Influence of LCST on fluorescence property of the polymer

Figure 3 shows the LCST stimulated fluorescence properties of the polymer. At 20 °C, an emission with a peak at 660 nm from the platinum porphyrin was observed. When the temperature is higher than its LCST, the emission intensity becomes stronger. The change is due to the nanostructure difference at the variable temperatures. At room temperature, the polymer is a unimer (Figure 2), the probe freely rotates and interacts efficiently with water. Thus low quantum efficiency was observed. When the temperature is higher than its LCST, the polymer starts to aggregate. The aggregated polymers provide hydrophobic and viscous microdomains to suppresses the rotation of the fluorophores and alleviate the interaction with water. This results in fluorescence efficiency enhancement. The utilization of the LCST property to increase the fluorescence intensity was reported by other scientists [30]. It should be noted that for the platinum porphyrin based oxygen probe in solutions and films, higher temperature usually results in lower fluorescence intensity [12–18]. This is because of the much faster molecular rotation at higher temperatures, which makes a more significant non-radioactive energy loss. Therefore, the LCST significantly changes the platinum porphyrin’s photophysical property.

Figure 3.

(a) Temperature-dependant fluorescence spectra of poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) at the constant oxygen partial pressure (21 kPa). (b) The corresponding emission intensity at 660 nm along the temperature change.

Oxygen response

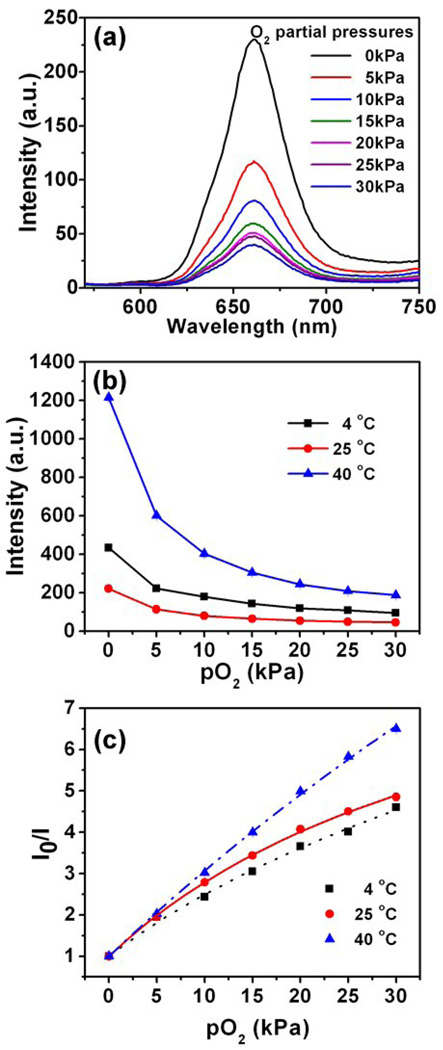

Figure 4a shows the oxygen response of poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) measured in water at ambient temperature. A marked dependence of fluorescence intensity on dissolved oxygen concentrations [O2] was observed, showing that the emission of the oxygen probe was physically quenched by oxygen. The intensity ratio (I0/I) did not show linear dependence on the concentration change, indicating the oxygen response of the polymer does not follow a linear Stern-Volmer quenching equation. However, the Stern-Volmer plot shows downward curvature and thus a deviation from linearity. Carraway et al. [34] proposed a “two-site model” which assumes the dye to be located in two regions of different microenvironment:

| (1) |

where f1 and f2 are the respective fractions of the total emission for each component, (with f1 + f2 being 1), KSV1 and KSV2 are the Stern-Volmer constants for each component, [O2] is the dissolved oxygen concentration which is proportional to the oxygen partial pressure (at 23 °C, [O2] in water is 8.57 mg/L at atmospheric pressure corresponding an oxygen partial pressure of 21 kPa), and I0 and I are the steady-state fluorescence signals measured in the presence of nitrogen and various oxygen concentrations generated by controlled gas bubbling, respectively.

Figure 4.

(a) Response to dissolved oxygen at room temperature. (b) Fluorescence intensity changes along the oxygen partial pressures at different temperatures (4, 25, 40 °C). (c) Stern-Volmer plots of poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) in water at different temperatures (4, 25, 40 °C).

Temperature dependent oxygen responses were given in Figure 4b. At the same oxygen partial pressure, the probe exhibits higher emission intensities at the low (4 °C) and the high temperature (40 °C) than at room temperature. This is quite interesting. As discussed before, for the oxygen probe, usually an increase in temperature will result in a decrease of the emission intensity, because the oxygen probe rotates and interacts with water more freely at higher temperature. Therefore, low quantum efficiency was observed for polymer at 25 °C compared with at 4 °C. However, the LCST plays a critical role for the polymer aggregation to change the microenvironment of the oxygen probes in the Poly(NIPAAm) matrix, which endows an increase of the fluorescence intensity for polymer in 40 °C compared with that at 25 °C.

The two-site model fits the experimental findings very well (Figure 4c) below the LCST, in that R2 in all cases is better than 0.996. A fit gave values of 0.886 for f1 and 0.114 for f2 at 4 °C, while at 25 °C the fit gave values of 0.904 for f1 and 0.096 for f2. The first KSV1 increases strongly with temperature (from 0.201 to 0.244 kPa−1 for 4 °C to 25 °C). As expected, the poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) exhibits higher sensitivity to oxygen at elevated temperatures (Figure 4c). Such behavior is common for many optical oxygen sensors [35–38], because the higher temperature causes both higher oxygen diffusion in the polymer and more efficient interactions of the probes with oxygen molecules [34]. Interestingly, when the temperature is increased above the LCST, the polymer exhibits a different oxygen-quenching dynamic, which is close to linear. A “two-site model” can fit the data well with R2 is larger than 0.9997, giving values of 0.973 for f1 and 0.027 for f2. This indicates that dye is mainly localized at the first site, giving the first Stern-Volmer constants KSV1 of 0.225 kPa K−1.

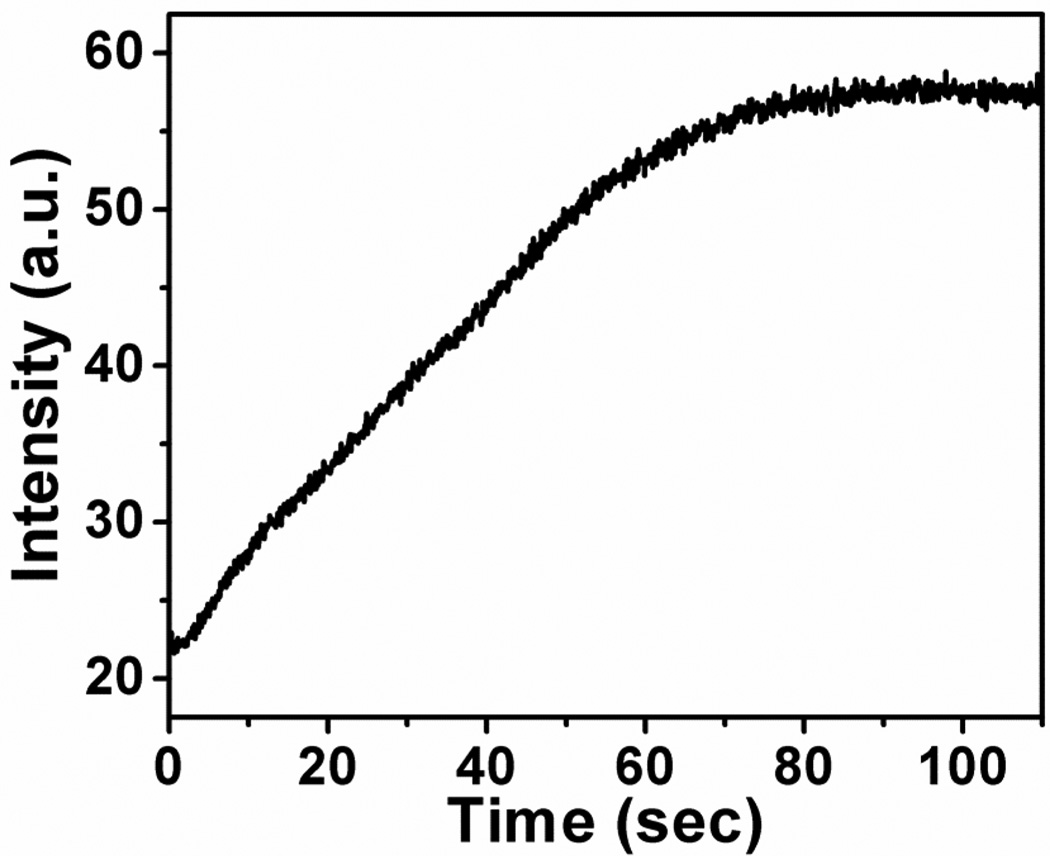

Response time is an important factor for sensing. Figure 5 shows the course of enzymatic reaction of glucose oxidation monitored with help of the oxygen-sensitive copolymer at a stationary condition. The apparent response of the copolymer is 70 s, which is the overall time needed for mixing the enzyme and enzymatic reaction itself. In fact, when the experiment is executed under stirring of the anaerobe solution, the whole signal change occurs within 2 s. Like the oxygen nanosensor prepared by incorporating PtTFPP in polystyrene-block-polyvinylpyrrolidone beads [38], the copolymer introduces virtually no diffusional barrier for diffusion-limited quenching processes (Figure 5), so real time monitoring of fast processes becomes possible.

Figure 5.

Course of enzymatic oxidation of glucose monitored using poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin). The concentration of glucose is 0.25 M. 60 µL of glucose oxidase solution (C = 10 mg/mL) was added to the test solution (V = 3 mL). The experiment was performed at 25 °C.

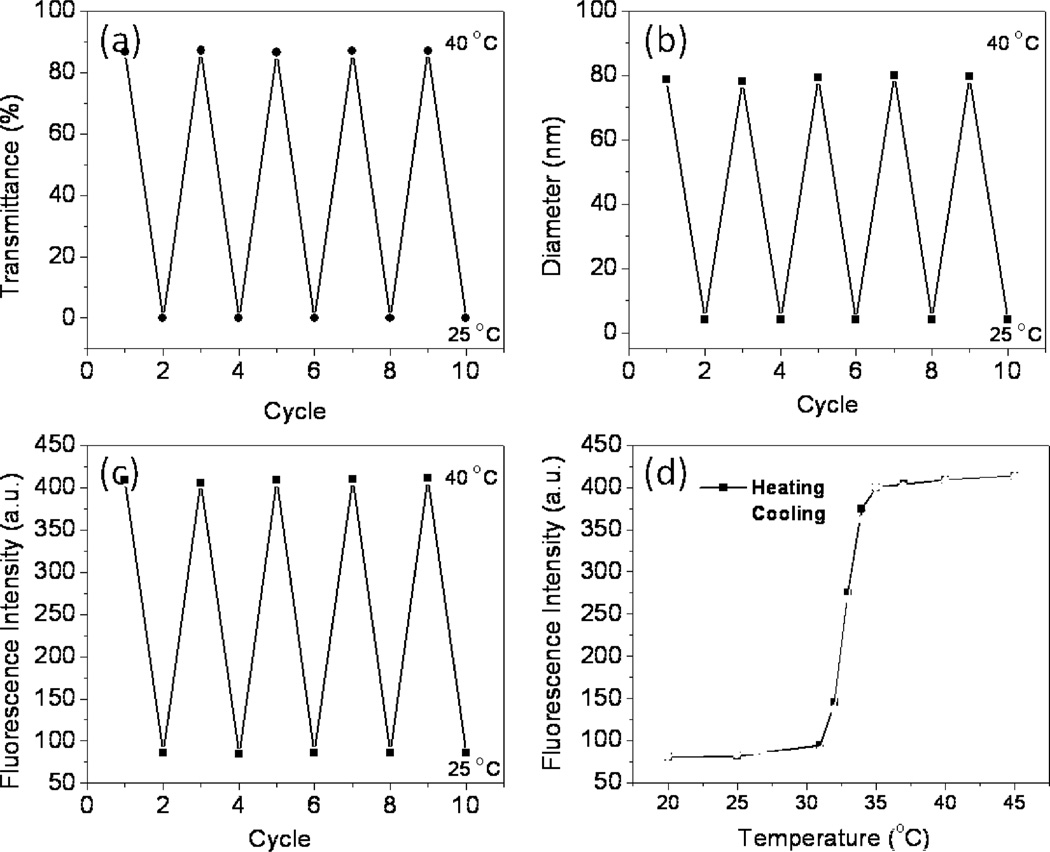

Reversibility

The fluorescence enhancement/quenching of poly(NIPAMm-co-PtPorphyrin) occurs reversibly, regardless of the heating/cooling process. Figure 6 shows the change in transmittance (6a), average diameters (6b), and fluorescence intensity (6c), where the temperature is changed repeatedly between 25 and 40 °C. The data clearly show that the fluorescence intensity is reversibly changeable at least 10 times. In addition, as shown by red symbols in Figure 6d, the fluorescence intensity data obtained during a cooling sequence are almost the same as that obtained during a heating sequence (black symbols), as is observed for related PNIPAAm-based thermometers [30,39]. This indicates that this polymer allows a smooth structure change in response to the temperature change and allows a reversible fluorescence response.

Figure 6.

Change in transmittance (a), hydrodynamic diameter (b) and fluorescence intensity (c) of poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) in water, where the temperature was changed repeatedly between 25 and 40 °C. (d) Temperature-dependent change of fluorescence intensity (λem = 660 nm) of the poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) on heating (black) and cooling (red).

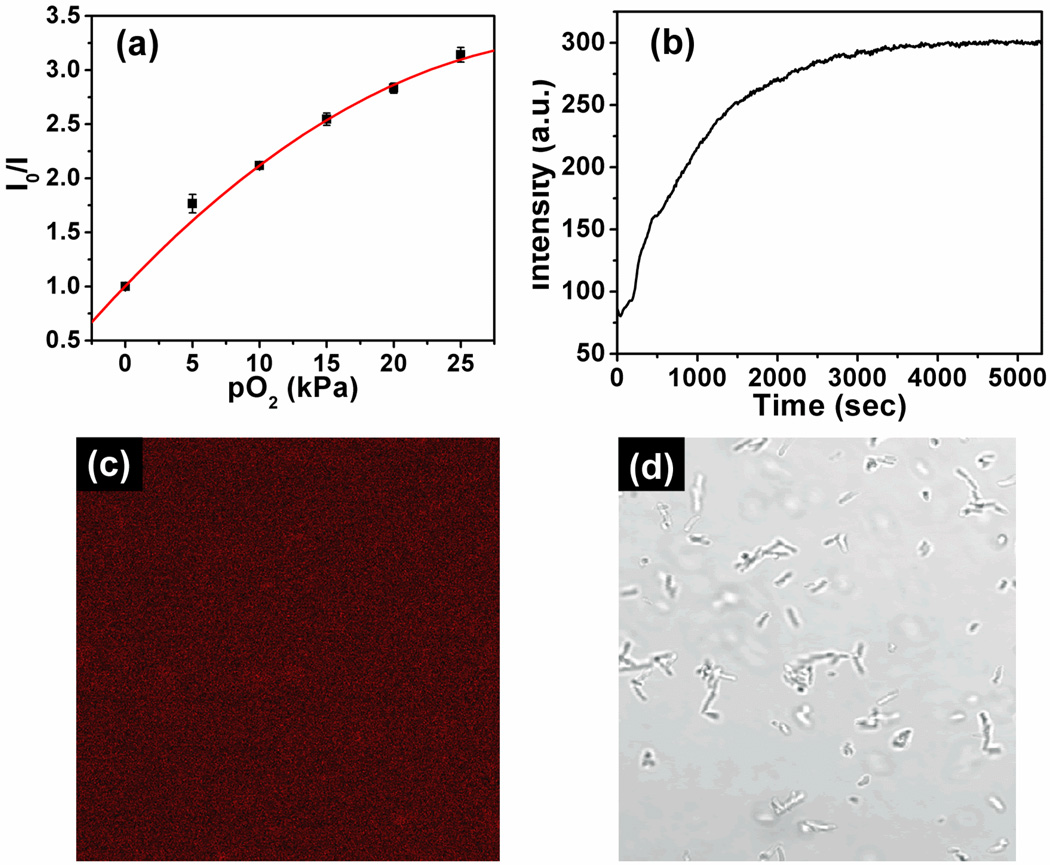

Preliminary application of poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) for DO monitoring during the growth of Escherichia coli (E. coli)

It is well known that generation time of prokaryotic E. coli is short, usually in the range of 20 to 90 minutes, depending on culture conditions including temperature and cell density [40,41]. This short growth time facilitates the use of E. coli for preliminary monitoring of extracellular dissolved oxygen concentration changes. E. coli can grow either in the presence or absence of oxygen because of its ability to use different metabolism pathways. During the growth process, the metabolism of E. coli consumes oxygen. To efficiently monitor oxygen concentration changes, a layer of mineral oil was added on the top of the LB medium to prevent the introduction of O2 from the air into the medium [2,42]. First the calibration plot for the poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) in LB media was achieved at different oxygen concentrations (0–25 kPa at atmospheric pressure) at 25 °C and is presented in Figure 7a. The response of the copolymer to oxygen still followed the “two-site model” Stern-Volmer equation. At 25°C, the first Stern-Volmer constant KSV1 in LB (0.127 kPa−1) is much less than in water (0.244 kPa−1). This phenomenon agrees with our previous published paper [36] because the additives (proteins and tryptone) in the LB media affected the sensors’ oxygen response. As can be seen in Figure 7b, for the initial E. coli density of 1 × 107 cfu/mL, clear oxygen consumption was observed during the growth periods. This is because the E. coli consumes oxygen present in the LB medium. After all the oxygen was consumed, the emission of the sensor reached a maximum and did not change with time. We also found our polymeric sensor is cell impermeable to the E. coli. Under the fluorescence microscope, there was no red emission observed (Figure 7c and 7d). This preliminary study indicates the polymer is applicable for extracellular oxygen consumption and metabolism activity investigation. The sensor has no influence on the growth of E. coli’ with a polymer concentration of 3 mg/mL cultured at 37 °C for 2 hours. The optical densities at 600 nm of the cells cultured with and without the polymer had no difference.

Figure 7.

(a) Stern-Volmer plot of poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) in LB media at ambient temperature. (b) Oxygen consumption monitored using poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) using the initial E. coli density of 107 cfu/mL. (c) Fluorescence confocal image of the E. coli after 3 hours internalization with poly(NIPAAm-co-PtPorphyrin) (3 mg/mL). (d) Bright field image of the E. coli after 3 hours internalization with the oxygen sensor.

Advantage/disadvantage of this fluorescent polymer for O2/T

Usually dual sensor systems are achieved in most cases by different fluorescent dyes with different optical emission filters, requiring clearly separable emission wavelengths of the two indicators with almost no spectral overlap [14]. Furthermore, energy transfer and other quenching interactions between the two indicators could possibly occur. Therefore, in practice, it is a high challenge to select such a combination of indicators. In this study, the temperature-sensitive response (Figure 3) of the copolymer is totally different from the oxygen-sensitive response (Figure 4) due to the concomitant change of transmittance of the solution and hydrodynamic radius of the polymer (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Therefore, data from the temperature-related response can be used to compensate the deviation in the oxygen partial pressure determination. Therefore, it is possible to use this polymer for dual oxygen and temperature measurement. Accurate determination of the temperature is confined in the range of 30–35 °C because the temperature response comes from the LCST property of the PNIPAAm backbone. There is also a disadvantage for real application when both temperature and oxygen concentration change, especially when the measurements of the transmittance becomes difficult. However, this study may provide a new strategy for the design of O2/T dual sensors.

On the other hand, it should be noted here, intensity based measurement is easily interfered by drift of optical probe, non-uniform local dye concentration, turbidity of sample, photobleaching or scattering effects. The use of decay time or lifetime will be advantageous when compared to intensity-based methods, not only because of the above mentioned problems but also because it is unnecessary to use an internal standard for lifetime measurements. Further, fluorescence decay time isn’t affected by excitation intensity and wavelength [13–17]. Therefore, it is expected lifetime based measurements may alleviate the above mentioned problems and show advantages for the dual temperature and oxygen sensing system. Further investigation for this dual sensing system using the lifetime based measurement is necessary to be explored.

4. CONCLUSIONS

A dual fluorescent sensor is presented here for sensing temperature and oxygen. The sensor exhibits temperature-dependant changes in fluorescence spectra in water, enabling an application in the temperature range of 30–35 °C. Meanwhile the sensor exhibits good response to the dissolved oxygen. In addition, the sensor can easily be prepared by copolymerizing commercially available NIPAAm with an oxygen-sensitive monomer. A successful preliminary application of the sensor was performed in a biological system, which was used to monitor oxygen consumption of E. coli. The simple material design presented here may contribute to the development of more efficient and useful functional materials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support was provided by the Microscale Life Sciences Center, a NIH Center of Excellence in Genomic Sciences at Arizona State University: Grant 5P50 HG002360, Dr. Deirdre Meldrum, PI, Director.

Biographies

Xianfeng Zhou received his BS and MS degrees from the Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Jilin University (China) in 2002 and 2004. In 2007, he received his PhD degree in polymer chemistry and physics from Jilin University. He worked as senior researcher at Wuxi Apptec. Co., Ltd. He is now working at the Center for Biosignatures Discovery Automation, Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University as a postdoc. His research interests are major on design and synthesis of optical sensors for application in biological systems.

Fengyu Su received her BS and MS degrees from the Department of Organic Chemistry, Jilin University (China) in 1990 and 1993, and her PhD degree in Polymer Physics and Chemistry from Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1997. She worked at Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, RIKEN Advanced Science Institute, Tokyo Metropolitan University, and University of Washington. She is now working at the Center for Biosignatures Discovery Automation of the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University as an Associate Research Scientist. Her research interests include development of polymer hydrogels and sensors, and application of optical sensors for biosensing and bioimaging.

Yanqing Tian received his BS and MS degrees from the Department of Organic Chemistry, Jilin University (China) in 1989 and 1992. In 1995, he received his PhD degree in polymer chemistry and physics from Jilin University. He worked at Jilin University, Sagami Chemical Research Center (Japan), Tokyo Metropolitan University, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo University of Science, and University of Washington. He is now working at the Center for Biosignatures Discovery Automation, Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University as a Research Assistant Professor. His research interests include synthesis and application of optical sensors and block copolymers for biosensing, bioimaging and drug delivery.

Roger H. Johnson has been a Research Scientist and Laboratory Manager in the Center for Biosignatures Discovery Automation in ASU’s Biodesign Institute since 2006. Roger is responsible for overall management of daily research activities in the Center, and leads the cell CT research. He has over twenty years’ experience in 3D micro-CT, and is an expert in CT scanner design and construction, image reconstruction algorithms, and 3D image processing and analysis. Prior to joining ASU, he was a tenured associate professor in Biomedical Engineering at Marquette University in Milwaukee, with appointments at the Medical College of Wisconsin (Departments of Biophysics and Radiology) and the Milwaukee VAMC Department of Physiology, where he built an X-ray microtomograph to study the lung microvasculature in animal models of pulmonary hypertension. Before moving to Marquette in 1996, he was Assistant Professor in Bioengineering and Radiology at The Ohio State University. Roger obtained his BA degree in German and chemistry from the University of Connecticut in 1979. This included a junior year abroad in Salzburg, Austria. From 1980 through 1987 he worked in the orthopedic implant field, both in industry and the hospitalbased research setting. It was this pursuit that led him to the practice and the study of 3D medical imaging, first with light and electron microscopy, then using other modalities including CT, MRI, and PET. He returned to complete the PhD in Bioengineering at the University of Washington from 1987 to 1995. For his dissertation research, he designed and built an X-ray microscope and X-ray microtomograph for point-projection data acquisition of biological specimens. Dr. Johnson is co-inventor of the cell CT and has seven patents including two on X-ray and two on optical microtomography.

Deirdre R. Meldrum, ASU Senior Scientist, Professor of Department of Electrical Engineering at Arizona State University, is also director of the Center for Biosignatures Discovery Automation at the Biodesign Institute. In addition, Meldrum directs a National Institutes of Health Center of Excellence in Genomic Sciences called the Microscale Life Sciences Center. Her research interests include genome automation, microscale systems for biological applications, single cell technologies for understanding cancer and inflammation, ecogenomics, robotics and control systems. Before joining ASU in 2007, Meldrum was on the faculty of the University of Washington in Seattle since 1992, where she founded and directed UW’s Genomation Laboratory. She is a member of the National Advisory Council for Human Genome Research, a Presidential Early Career Awardee for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE), fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), and fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). She received her BS in Civil Engineering from University of Washington, her MS in electrical engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and her PhD in electrical engineering from Stanford University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tierney MJ, Kim HOL. Anal. Chem. 1993;65:3435–3440. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomas CO, Deirdre B, Vladimir O, Rosemary O, Dmitri BP. Anal. Biochem. 2000;278:221–227. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang XD, Chen X, Xie ZX, Wang XR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:7450–7453. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagl S, Wolfbeis OS. Analyst. 2007;132:507–511. doi: 10.1039/b702753b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lidstrom ME, Meldrum DR. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;1:158–164. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molter TW, McQuaide SC, Suchorolski MT, Strovas TJ, Burgess LW, Meldrum DR, Lidstrom ME. Sens. Actuators, B. 2009;135:678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi M. Pacific. Sci. 1974;28:123–138. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pechenik JA. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1984;74:241–257. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrell J, Rose AH. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1967;21:101–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.21.100167.000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li C, Li S, Dong B, Liu Z, Song C, Yu Q. Sens. Actuators, B. 2008;134:313–316. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gota C, Okabe K, Funatsu T, Harada Y, Uchiyama S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2766–2767. doi: 10.1021/ja807714j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchiyama S, Matsumura Y, de Silva AP, Iwai K. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:5926–5935. doi: 10.1021/ac0346914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlos B, Stefan N, Michael S, Mario NBS, Otto SW. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:6449–6457. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthias IJS, Stefan N, Otto SW, Ulrich H, Michael S. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008;18:1399–1406. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anna SK, Sergey MB, Christian K, Otto SW. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:8486–8493. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sergey MB, Otto SW. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:5094–5101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sergey MB, Anna SV, Christian K, Otto SW. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006;16:1536–1542. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muhammet EK, Bruce FC, Kirk SS. Langmuir. 2005;21:9121–9129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haley TJ, Komesu N, Colvin G, Koste L, Upham HC. J. Pharm. Sci. 1965;54:643–645. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600540435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feil H, Bae YH, Feijen J, Kim SW. Macromolecules. 1993;26:2496–2500. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heskins M, Guillet JE. J. Macromol. Sci. Chem. 1968;A2:1441–1445. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winnik FM. Macromolecules. 1990;23:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gan DJ, Lyon LA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:8203–8209. doi: 10.1021/ja015974l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee CF, Wen CJ, Lin CL, Chiu WY. J. Polym. Sci. A: Polym. Chem. 2004;42:3029–3037. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyata T, Asami N, Uragami T. Macromolecules. 1999;32:2082–2084. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka T, Wang C, Pande V, Grosberg AY, English A, Masamune S, Gold H, Levy R, King K. Faraday. Discuss. 1995;101:201–206. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon OH, Kikuchi A, Yamato M, Sakurai Y, Okano TJ. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000;50:82–89. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200004)50:1<82::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li YY, Zhang XZ, Zhu JL, Cheng H, Cheng SX, Zhuo RX. Nanotechnology. 2007;18:215605–215612. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergbreiter DE, Case BL, Liu YS, Caraway JW. Macromolecules. 1998;31:6053–6062. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang DP, Miyamoto R, Shiraishi Y, Hirai T. Langmuir. 2009;25:13176–13182. doi: 10.1021/la901860x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiraishi Y, Miyamoto R, Hirai T. Langmuir. 2008;24:4273–4279. doi: 10.1021/la703890n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obata M, Tanaka Y, Araki N, Hirohara S, Yano S, Mitsuo K, Asai K, Harada M, Kakuchi T, Ohtsuki C. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2005;43:2997–3006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang CC, Tian YQ, Jen AK-Y, Chen WC. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. 2006;44:5495–5504. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carraway ER, Demas JN, DeGraff BA. Anal. Chem. 1991;63:337–342. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillanders RN, Tedford MC, Crilly PJ, Bailey RT. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2005;545:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian YQ, Shumway BR, Meldrum DR. Chem. Mater. 2010;22:2069–2078. doi: 10.1021/cm903361y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Payne SJ, Fiore GL, Fraser CL, Demas JN. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:917–921. doi: 10.1021/ac9020837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borisov SM, Mayr T, Klimant I. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:573–582. doi: 10.1021/ac071374e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uchiyama S, Kawai N, de Silva AP, Iwai K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3032–3033. doi: 10.1021/ja039697p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plank LD, Harvey JD. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1979;115:69–77. doi: 10.1099/00221287-115-1-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wheelis M. Principle of Modern Microbiology. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publisher; 2008. p. 195. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sattley WM, Madigan MT. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007;272:48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]