Abstract

Background & objectives:

It was hypothesized that both thrombogenic and atherogenic factors may be responsible for premature coronary heart disease (CHD) in young Indians. A case-control study was performed to determine cardiovascular risk factors in young patients with CHD in India.

Methods:

Successive consenting patients <55 yr with an acute coronary event or recent diagnosis of CHD were enrolled (cases, n=165). Age- and gender-matched subjects with no clinical evidence of CHD were recruited as controls (n=199). Demographic, anthropometric, clinical, haematological, and biochemical data were obtained in both groups. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were performed to identify important risk factors.

Results:

In cases vs. controls mean systolic BP, diastolic BP, platelet counts, LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and fibrinogen were higher and HDL cholesterol lower (P<0.001). The presence of current smoking, low fruit and vegetables intake, high fat intake, hypertension, diabetes, low HDL cholesterol, and high LDL cholesterol, total:HDL ratio, fibrinogen and homocysteine was significantly higher in cases (P<0.05). Multivariate logistic regression analysis (age adjusted odds ratio, 95% confidence intervals) revealed that smoking (19.41, 6.82-55.25), high fat intake (1.66, 1.08-2.56), low fruit and vegetables intake (1.99, 1.11-3.59), hypertension (8.95, 5.42-14.79), high LDL cholesterol [2.49 (1.62-3.84)], low HDL cholesterol (10.32, 6.30-16.91), high triglycerides (3.62, 2.35-5.59) high total:HDL cholesterol (3.87, 2.35-5.59), high fibrinogen (2.87, 1.81-4.55) and high homocysteine (10.54, 3.11-35.78) were significant.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Our results showed that thrombotic (smoking, low fruit/vegetables intake, fibrinogen, homocysteine) as well as atherosclerotic (hypertension, high fat diet, dyslipidaemia) risk factors were important in premature CHD. Multipronged prevention strategies are needed in young Indian subjects.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, cholesterol, coronary heart disease, fibrinogen, India, risk factors

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is epidemic in India1 characterized by premature onset and high mortality. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that while more than 70 per cent of coronary deaths occur in subjects older than 70 yr in North America and Western Europe, in India and other developing countries 70 per cent deaths occur in subjects less than 70 yr of age1. Factors of risk for the premature CHD in Indian subjects could be multiple, ranging from social, economic, psychological, lifestyle (smoking, sedentary lifestyle, improper diet) and biological (abnormal lipids, hypertension, diabetes, obesity)2. Genetic factors such as mutations at specific chromosomal locations and single nucleotide polymorphisms have also been implicated3. The INTERHEART case-control study reported that nine established risk factors (high apolipoprotein B/A1 ratio, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, psychosocial stress, low fruit and vegetables intake, low alcohol intake and sedentary lifestyle), explained more than 90 per cent of acute myocardial infarction4. Prospective cohort studies in developed countries have identified that five major cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, hypertension, high LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol and diabetes) are associated with CHD5. These studies also reported that more than 90 per cent of acute coronary events can be predicted by major coronary risk factors5.

Previous case-control studies from India have reported importance of smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and abnormal lipids6–9. Individual studies have also studied novel risk factors such as lipid subtypes, lipoprotein(a), insulin resistance, homocysteine, and dietary factors2. Large studies for identification of risk factors for premature CHD among Indian subjects are not available and most are limited to 50-100 subjects1,2. We hypothesized that thrombogenic risk factors (e.g., smoking, dietary antioxidant deficiency, fibrinogen, platelet functions, etc.) are important in premature CHD in Indians. To test this hypothesis a case-control study was performed to identify association of multiple vascular risk factors, both thrombogenic and atherogenic, in subjects (≤55 yr age) with an acute coronary event (myocardial infarction or unstable angina) or recent angina.

Material & Methods

The study protocol was approved by institutional ethics committee and a proforma was prepared for collection of data for socio-demographic characteristics such as education, occupation, income and housing status for classification of socio-economic status; previous history of risk factors such as smoking or tobacco use, hypertension, diabetes; and treatment of chronic diseases. Physical examination focused on measurement of height and weight as soon as the patient was ambulant. Blood (9-10 ml) was collected within 24 h of admission for estimation of haematological and biochemical parameters using EDTA and plain vials respectively. Premature CHD was defined as first manifestation before 55 years in both men and women as per current guidelines2.

Successive consenting patients with an acute coronary event (ST elevation or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina) presenting to SP Medical College and Associated Group of Hospitals, Bikaner, Rajasthan during October 2003 to September 2006 were enrolled as cases. Those with past history of acute coronary event or those with stable angina hospitalized for routine investigations were excluded. Age- and gender-matched subjects with no clinical evidence of CHD were recruited from other hospital areas such as surgical wards, blood banks, and outpatient clinics as controls.

Demographic (occupation, socio-economic status), dietary, anthropometric (body mass index, BMI), clinical (blood pressure, BP), haematological (haemoglobin, leucocyte counts, platelet counts, platelet distribution width), and biochemical [total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, calculated non-HDL cholesterol, calculated low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, fibrinogen, homocysteine] data were collected in both groups. The investigators were trained in questionnaires and dietary assessment. Dietary data were collected using a modified validated food frequency questionnaire10. This questionnaire uses recall over a 12-month period. Anthropometric measurements were performed according to WHO guidelines11. Haematological parameters were measured using Coulter automated cell counter. Lipids were measured using standardized biochemical methods reported earlier12. Fibrinogen and homocysteine were measured using ELISA techniques.

Statistical analyses: Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± 1 standard deviation or in per cent. All the anthropological and biochemical variables followed a normal distribution with low skew and kurtosis. As the sample size was large, case-control comparisons were performed using z-test or chi-square test as appropriate. Prevalence of risk factors was determined using standard guidelines reported earlier12. For determining associations of CHD with various risk factors univariate logistic regression analysis was performed for calculation of odds ratios (OR) and 95 per cent confidence intervals (CI) using SPSS statistical program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA; Version 10.0). Age-adjusted ORs and 95 per cent CIs were calculated after imputing age in the regression equation. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was then performed after adjusting for risk factors found important on univariate analyses. For a given independent risk factor, multivariate analyses were performed after adding all the other risk factors jointly. Thus, we included the INTERHEART study4 risk factors and others found important in the present study (smoking, low fruits and vegetable intake, high fat intake, obesity, hypertension, known diabetes, high LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol and high triglycerides) following the age-adjustment. Subsequently, addition of emerging risk factors (fibrinogen and homocysteine) was done jointly and ORs determined. P<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

A total of 250 subjects who consecutively presented to the department were enrolled, however, all clinical and biochemical details were available for 165 (152 men and 13 women) patients (acute ST elevation myocardial infarction 97, acute coronary syndromes 56, newly diagnosed stable angina 12). Age- and gender-matched controls (n=199) were also recruited.

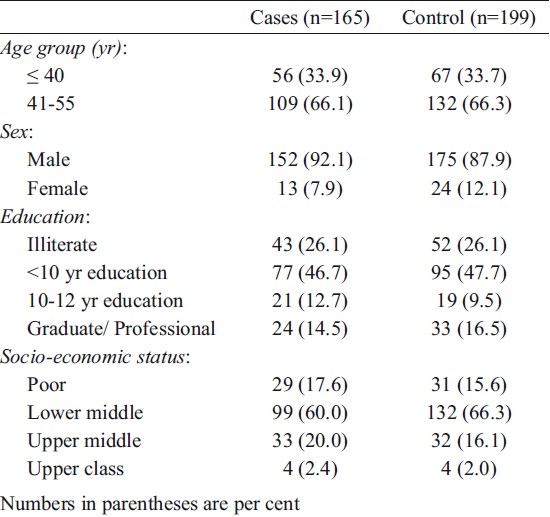

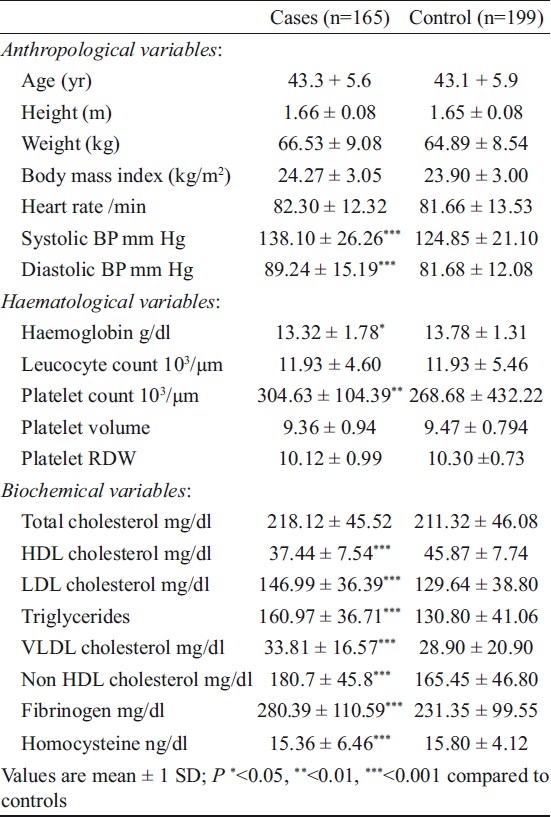

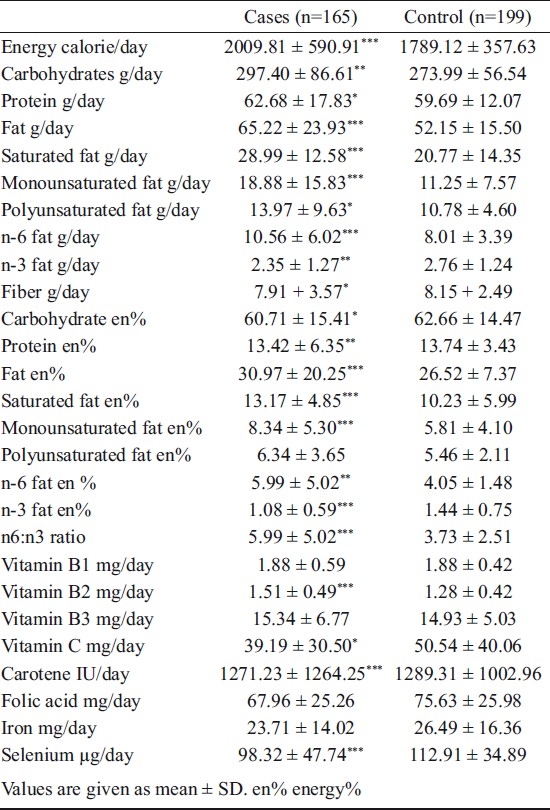

The demographic characteristics are shown in Table I. The cases and controls were well matched for age and other socio-economic characteristics. Level of literacy and socio-economic status were also similar. Mean values of various biological variables including physical measurements, BP, and haematological and biochemical variables in cases and controls are shown in Table II. The mean weight, height and BMI were not significantly different while systolic and diastolic BP was higher in cases (P<0.001) compared to controls. Total platelet counts were significantly more (P<0.05) in cases while platelet volume and platelet random distribution width was similar. Mean total cholesterol levels were not significantly different in cases and controls. Mean HDL cholesterol was significantly lower and non-HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides significantly greater in cases (P<0.001) than in controls. Mean fibrinogen levels were significantly (P<0.001) greater in cases and homocysteine levels not significantly different. Analysis of food intake showed that, in cases vs controls, intake (g/day) of pulses and legumes (18.8 ± 22.5 vs 25.1 ± 27.2), roots and tubers (60.0 ± 57.7 vs 90.7 ± 80.9), green leafy vegetables (10.0 ± 20.1 vs 15.1 ± 32.2), other vegetables (50.1 ± 64.4 vs 147.0 ± 102.8) and fruits (13.9 ± 32.7 vs 50.5 ± 56.0) was significantly lower (P<0.01) in cases. The intake (g/day) of milk and its products (456.7 ±199.6 vs 356.8 ± 242.2), visible fats and oils (15.7 ± 5.8 vs 14.0 ± 5.5), ghee (13.8 ± 19.0 vs 1.5 ± 6.7), deep fried food (15.2 ± 25.0 vs 1.0 ± 5.1) and shallow fried foods (24.0 ± 60.4 vs 2.7 ± 17.2) was more in cases (P<0.01). Intake of total calories as well as various macronutrients such as fats, saturated fats, mono- or polyunsaturated fats was significantly more (P<0.001) in cases while n-3 fats higher in controls. Intakes of various nutrients after adjustment for energy intake (energy%) revealed that intake of total fats, mono- and polyunsaturated fats and n-6 fats was more and intake of n-3 fats lower in cases. Intake of vitamin C, folic acid and selenium was lower in cases. There was no difference in intake of other proximate factors or micronutrients (Table III).

Table I.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study subjects

Table II.

Anthropometric, haematological and biochemical variables

Table III.

Intake of various proximate and micronutrients

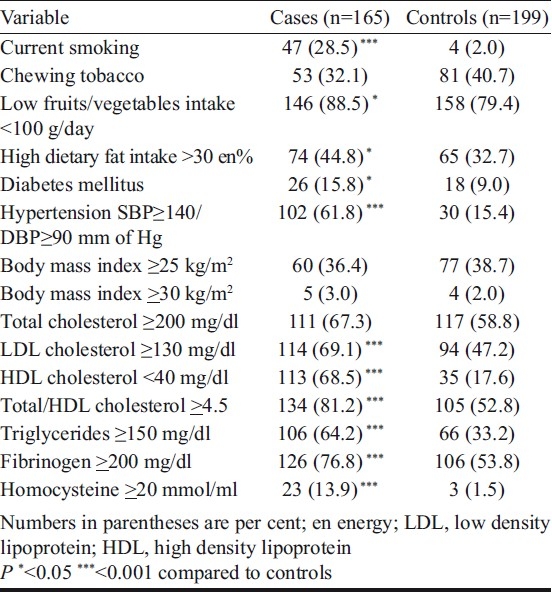

Presence of various risk factors was also determined in the study subjects (Table IV). In cases vs controls presence of current smoking (28.5 vs 2.0%), low fruit and vegetables intake (88.5 vs 79.4%), high fat intake >30en per cent (44.8 vs 32.7%), known diabetes mellitus (15.8 vs 9.0%), hypertension (61.8 vs 15.4%), high LDL cholesterol ≥130 mg/dl (69.1 vs 47.2%), total:HDL cholesterol ≥4.5 (81.2 vs 52.8%) and triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl (64.2 vs 33.2%) was significantly higher. Hyperfibrinogenaemia levels >200 mg/dl (76.8 vs 53.8%) as well as hyperhomocysteinaemia >20 ng/ml (13.9 vs 1.5%) were more in cases.

Table IV.

Presence of cardiovascular risk factors

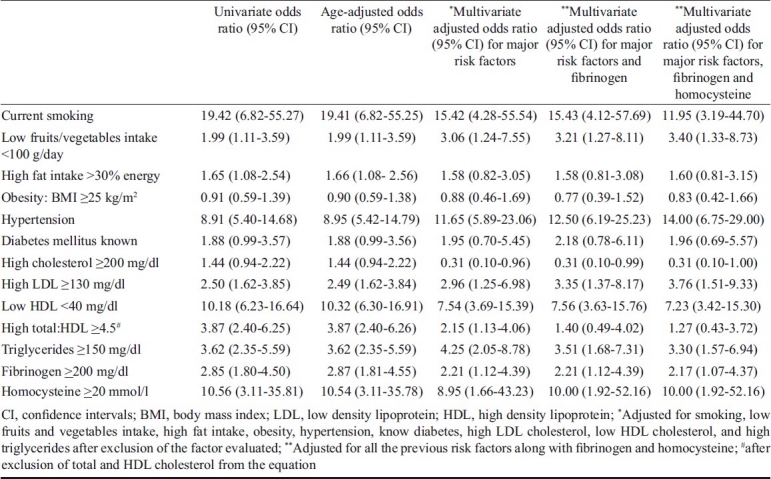

Univariate, age-adjusted and multivariate adjusted ORs for association of risk factors with CHD are shown in Table V. On univariate as well as age-adjusted analyses significant associations are observed with current smoking, low fruit and vegetables intake, high fat intake, hypertension, known diabetes, high LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, high total:HDL cholesterol ratio, high triglycerides, high fibrinogen and high homocysteine levels. No association is observed with poverty (age-adjusted OR 1.18, CI 0.67-2.07), illiteracy (OR1.18, CI 0.96-1.04) and obesity (OR 0.90, CI 0.59-1.38). Multivariate analysis after adjustment for age, smoking, fruits and vegetable intake, fat intake, obesity, hypertension, known diabetes and lipid abnormalities showed that significance of smoking, low fruits and vegetables intake, hypertension, low HDL cholesterol, high triglycerides, high fibrinogen and high homocysteine persisted (P<0.05). Further adjustment after addition of fibrinogen and homocysteine revealed persisting importance of smoking, low fruit and vegetable intake, high fat intake, hypertension, low HDL cholesterol and high triglycerides. To determine influence of fruits and vegetables intake on risk from homocysteine a step-wise analysis of association of CHD with homocysteine was done. Significance of univariate OR (10.56, CI 3.11-35.81) persisted after addition of age (OR 10.54, CI 3.11-35.78), fruits and vegetables intake (OR, CI) as well as addition of all the other risk factors (OR 8.95, CI 1.66-43.23).

Table V.

Odds ratios and 95 per cent confi dence intervals for association of risk factors with premature coronary heart disease

Discussion

This study showed that thrombotic factors (smoking, low fruit and vegetables intake, high fibrinogen, high homocysteine) as well as atherogenic factors (high fat diet, hypertension, high LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol and high triglycerides) were important in the development of premature CHD. Thrombotic risk factors have been considered more important in premature CHD in studies from India. Previous case-control studies in premature CHD from India reported smoking, hypertension and low HDL cholesterol as important risk factors1,2,4. The present study also showed the importance of both thrombogenic and atherogenic risk factors. This finding is similar to the studies on premature CHD in developed countries5,13. Studies among older CHD patients in India such as the INTERHEART4 and others6–9 reported that multiple thrombogenic and atherogenic risk factors such as smoking, high apolipoprotein B, known hypertension or diabetes, high waist-hip ratio (WHR), psychosocial factors, lack of exercise and low fruit and vegetables consumption are important. The INTERHEART study also reported that younger age of onset of major risk factors explained the premature CHD in South Asians4. Epidemiological studies have reported younger age of onset of metabolic cardiovascular risk factors14.

The highest risks for CHD in the present study were smoking, low fruit and vegetables intake, hypertension and low HDL cholesterol similar to studies among the premature CHD in high income countries13. In INTERHEART study the adjusted ORs for these risk factors were significantly lower15. The age-adjusted and multivariate-adjusted ORs, for smoking, daily fruits and vegetables intake, hypertension and high ApoB/ApoA1were substantially lower than the present study. It is likely that these risk factors are more important in younger patients. Our study also shows that emerging risk factors such as fibrinogen and homocysteine are important in young CHD patients. Prospective studies have identified fibrinogen as important cardiovascular risk factor16. Role of high homocysteine as cardiovascular risk factor is well established17 and the present study shows that high levels are associated with increased risk even after multivariate adjustments. Previous case-control studies from India did not report significant association with homocysteine unlike the present study1,2. It may be possible that this factor is important in younger patients but larger studies are needed to confirm this finding. The statistical distribution of homocysteine level is skewed and the numbers of controls with high homocysteine are small and this is a shortcoming. We did not find significant correlation with other haematological parameters including platelet size and platelet distribution which are markers of platelet activation18. The platelet counts were higher in cases than controls but this could be a marker of activation during an acute coronary event hence this was not analyzed further. Dietary factors were also studied and low fruit and vegetables intake was found to be associated with increased risk. Other associations noted were with high intake of fats, edible oils, ghee and fried foods and intake of saturated fats, mono- and polyunsaturated fat, n-6 fats and an inverse association with n-3 fats. A very low intake of ghee and shallow and deep fried foods in controls was surprising and might reflect either changing dietary habits or misreporting of fat intake. More studies are required although the dietary differences observed in the present study are similar to previous Indian studies7,8.

There were several limitations in this study. Case-control studies have large number of inherent biases especially in identification of controls. To minimize these, controls were included from the hospital as these would be from the same locations as cases. Similar strategy was used in the INTERHEART study4. Moreover, risk factors in controls were similar to population based studies in western India12 and, therefore, controls were representative of local population. Secondly, measurements of risk factors in hospitalized patients are fraught with errors. BP values are unstable after acute coronary event, lipid levels quickly change, fibrinogen levels increase, platelet counts increase and dietary recalls may be biased. Past history of hypertension and diabetes was asked and BP levels were measured at multiple times, lipid levels were measured within 24 h of admission but blood glucose levels were not measured for diagnosis of diabetes as performed in previous studies4,6. Thirdly, although the number of subjects was not large, it is the largest study of premature CHD in India. Fourthly, this was not a prospective study which could have definitely evaluated the potential impact of various risk factors. Fifthly, many emerging risk factors [lipoprotein(a), triglyceride remnants, lipid subtypes, insulin resistance, C-reactive protein, inflammatory factors] or genetic markers that have been implicated in premature CHD, were not studied2,3. And, finally, as the number of women in this study was small, the risk factors could not be generalized. The strengths of the study include a robust case-control design, large numbers, enrollment of fresh cases, and strict biochemical and statistical criteria for analyses.

In conclusion, this study shows that premature coronary artery disease in Indians is due to combination of thrombotic and atherosclerotic vascular risk factors. These risk factors are highly prevalent in the community1. Prevention and control of premature cardiovascular diseases in India needs urgent control of these factors. Improving lifestyles with tobacco cessation, diet modulation with more fruits and vegetables and lower fat intake, and increased physical activity are critical. Target oriented control of hypertension, lipid levels and glycaemia is required. The study adds that lowering fibrinogen and homocysteine using novel strategies as well as control of all the risk factors from an early age are essential to prevent premature disease.

Acknowledgments

The study was financially supported by ad-hoc grant number 5/4/1-5/2002/NCD-II of the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India.

References

- 1.Gupta R, Joshi P, Mohan V, Reddy KS, Yusuf S. Epidemiology and causation of coronary heart disease and stroke in India. Heart. 2008;94:16–26. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jomini V, Oppliger-Pasquali S, Wietlisbach V, Rodondi N, Jotterand V, Paccaud F, et al. Contribution of major cardiovascular risk factors to familial premature coronary artery dsiease: the GENECARD project. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:676–84. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson PWF. Progressing from risk factors to omics. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2008;1:141–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.815605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi P, Islam S, Pais P, Reddy S, Dorairaj P, Kazmi K, et al. Risk factors for early myocardial infarction in South Asians compared with individuals in other countries. JAMA. 2007;297:286–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenland P, Knoll MD, Stamler J, Neaton JD, Dyer AR, Garside DB, et al. Major risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2003;290:891–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pais P, Pogue J, Gerstein H, Zachariah E, Savitha D, Jayprakash S, et al. Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Indians: a case-control study. Lancet. 1996;348:358–63. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rastogi T, Reddy KS, Vaz M, Spiegelman D, Prabhakaran D, Willett WC, et al. Diet and risk of ischemic heart disease in India. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:582–92. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patil SS, Joshi R, Gupta G, Reddy MV, Pai M, Kalantri SP. Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in a rural population of central India: hospital based case-control study. Natl Med J India. 2004;17:189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain P, Jain P, Bhandari S, Siddhu A. A case-control study of risk factors for coronary heart disease in urban Indian middle-aged males. Indian Heart J. 2008;60:233–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singhal S, Gupta P, Mathur B, Banda S, Dandia R, Gupta R. Educational status and dietary fat and anti-oxidant intake in urban subjects. J Assoc Physicians India. 1998;46:684–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Technical Report Series No. 854. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta R, Gupta VP, Sarna M, Bhatnagar S, Thanvi J, Sharma V, et al. Prevalence of coronary heart disease and risk factors in an urban Indian population: Jaipur Heart Watch-2. Indian Heart J. 2002;54:59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falk E, Shah PK. Pathogenesis of atherothrombosis. In: Fuster V, Topol EJ, Nabel EG, editors. Atherothrombosis and coronary artery disease. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. pp. 451–65. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta R, Misra A, Vikram NK, Kondal D, Sengupta S, Agrawal A, et al. Younger age of escalation of cardiovascular risk factors in Asian Indian subjects. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. INTERHEART study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danesh J, Lewington S, Thompson SG, Lowe GD, Collins R, Kostis JB, et al. Fibrinogen Studies Collaboration. Plasma fibrinogen levels and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;294:1799–809. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Homocysteine Studies Collaboration. Homocysteine and risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288:2015–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu SG, Becker RC, Berger PB, Bhatt DL, Eikelboom JW, Konkle B, et al. Mean platelet volume as a predictor of cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:148–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]