Abstract

Background & objectives:

Fas receptor and Fas Ligand (FasL) system has been implicated in the resistance to apoptosis, insensitivity to chemotherapy and in providing immune privileged status to most of the tumours. However, no reports are available on Fas and FasL expression in patients with tobacco-related oral carcinoma. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to observe Fas and FasL expression and their correlation with clinicopathological features as well as cell cycle parameters.

Methods:

Immunohistochemistry for Fas, FasL and DNA flow cytometry for cell cycle parameters was successfully done on 41 paraffin embedded tumour and 10 normal samples. The results were evaluated for possible association of Fas and FasL with clinicopathological features and cell cycle parameters.

Results:

Weak Fas expression was observed on the cell membrane only in 2 of 41 (5%) oral tumours while FasL immunoreactivity was seen in 26 of 41 (63.4%) tumours. In contrast, all ten normal oral tissues exhibited strong cytoplasmic and membrane Fas receptor immunoreactivity but absence of FasL staining. Older patients, greater tumour size and lymph node positivity were found to be associated with high expression of FasL. Significantly higher (P<0.01) expression of FasL was observed in oral tumours with aggressive DNA pattern like aneuploidy and high S-phase fraction.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Downregulation of Fas receptor and up-regulation of Fas ligand appear to be an important feature of tobacco-related intraoral carcinoma. Association of FasL expression with advanced clinical stage and aggressive DNA pattern suggests that the Fas and FasL system may be used as an important prognostic variable in patients with tobacco-related intraoral squamous cell carcinoma.

Keywords: DNA ploidy, Fas, FasL, oral cancer

Fas (CD95 or APO-1), is a 36-kDa cell surface protein that belongs to a large family of TNF receptors1. Fas Ligand (FasL or CD178) is a type II membrane protein of 40 kDa that binds to Fas2. Activation of Fas with FasL induces apoptosis in normal and tumour cells. The Fas-mediated cell death pathway includes cell death transactivation adaptor molecule (FADD/MORT 1) with a death domain and a FADD-associated caspase-8 (FLICE/MACH)3,4 that forms death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) resulting in apoptotic cell death. Thus, Fas and FasL system has been implicated in the establishment and escape of tumours from immune surveillance5,6 of the host. It has been proposed that an immuno-privileged status for tumour is established via the Fas mediated apoptosis of tumour-specific lymphocytes7. The decreased expression of Fas and/or increased expression of FasL favours malignant transformation and tumour progression4.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is one of the most common malignancy affecting males in India. The National Cancer Registry established by the Indian Council of Medical Research has also unequivocally reported that while India is one of the few countries in the world with a very low overall incidence of cancer, about 48 per cent of cancer reported in males and 20 per cent in females are tobacco related cancer of the oral cavity8. These tumours may remain localized for a longer time in some cases while in others it grows very fast and becomes inoperable in a short period suggesting a role of host immunity in such peculiar biological behaviour9. We have earlier shown an altered Fas and FasL expression on peripheral blood T-cells as well as Fas and FasL mediated apoptosis of the major T-cell subsets as a possible mechanism for the downregulation of immune functions and reduced apoptosis of tumour cells in patients with tobacco related oral squamous cell carcinoma10,11. We have also reported higher frequency of aneuploidy and higher S-phase fraction in oral tumours that was related to advanced clinical stage, lymph node metastasis, poor histological differentiation and early recurrence12. However, reports on Fas and FasL expression and their relation to clinicopathological features and cell cycle parameters in oral cancer are scanty. Therefore, the present study was planned to study Fas and FasL expression in patients with tobacco-related intraoral squamous cell carcinoma and their correlation with clinicopathological features and aggressive DNA pattern as determined by DNA flow cytometry.

Material & Methods

Study subjects: A cohort of randomly selected 41 patients with intra-oral cancer operated at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, between 2001-2006 were included in the study. Age of the patients ranged from 27 to 75 yr with a mean age of 53.0 ± 12.3 yr; 33 (80.5%) patients were males while 8 (19.5%) were females. All patients had history of tobacco chewing for periods ranging from 5 to 25 yr. The most commonly affected sites were lower alveolus (46%), buccal mucosa (27%), tongue (10%), followed by other sites like lower lip, retromolar trigone, gingivo-buccal sulcus and floor of the mouth. None of the patients had received pre-operative radiation or chemotherapy before the biopsy was taken. Tumour, node and metastasis (TNM) classification and clinical staging of the tumour were performed as per criteria laid down by American Joint Committee on Cancer13. Since only a few patients presented with T1 and T3 tumours, all were divided into two groups T1/T2 and T3/T4 for the analysis of data. Ten histologically normal oral tissue samples obtained from the otorhinolaryngology clinic served as control. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences and informed consent was obtained from all study subjects.

Histopathological examinations: Histopathological analysis was performed on primary tumours on haematoxylin and eosin stained sections. Histological grade was determined as per standard criteria13. Of the 41 patients with primary tumours, 30 had well differentiated, 11 presented with moderately differentiated and none with poorly differentiated tumours. Paraffin blocks containing more than 70 per cent of tumour area were selected for sectioning for immunohistochemical and flow cytometric studies.

Immunohistochemistry for Fas and FasL: The Fas and FasL expression was studied in formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded tissues by the standard immunohistochemical technique on 5 micron paraffin sections using Streptavidin – biotin Universal Detection Kit (Immunotech, France). Briefly, after sequential rehydration through acetone, ethanol and distilled water, the endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3 per cent H2O2 in methanol at room temperature for 5 min. The sections were washed with water and antigen was retrieved by heating sections in microwave (700 W) in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min. Before incubation in antibody solution, the sections were covered with protein blocking agent (PBA) for 5 min at room temperature, excess PBA was taped off and sections were covered with mouse monoclonal anti-Fas/FasL antibody (1:75 dilution; Neomarkers, Lab Vision Corporation, Fremont, CA) for 2 h in a wet chamber. The sections were washed and treated with biotinylated secondary antibody (anti-mouse 1gG) for 30 min at room temperature followed by treatment with streptavidin-peroxidase for 30 min at room temperature. The colour was developed using freshly prepared chromogen, diaminobenzidine (DAB) from commercially available kit (Immunotech, France) as per manufacturer's instructions. The sections were counter-stained with Mayer's haematoxylin and mounted with D.P.X. mountant. Similarly stained prostate tissue served as positive control while negative control slide was prepared by omitting primary antibody. Ten similarly stained normal oral tissue samples were included for comparison of the data. Slides were examined under light microscope and scored positive in case with membrane and cytoplasmic staining of more than 10 per cent cells in at least three randomly selected areas of dense staining.

DNA flow cytometry: Flow cytometry was performed on nuclei prepared from 30 μM thick sections from formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue by the modified technique of Hood et al14, as described earlier12. Briefly, sections were de-paraffinized with xylene and re-hydrated with changes in graded ethanol followed by two washes with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4). The samples were subjected to chemical digestion by incubating with 0.5 per cent pepsin (pH 1.5) at 37°C in water bath for 30 min with intermittent stirring. Disaggregated tissues were filtered through a 50 μm nylon mesh, washed twice and re-suspended in PBS. The cell suspension was fixed by adding cold ethanol and labelled with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) with 0.01 per cent Triton X and RNAse (1 mg/ml, Sigma, USA) at room temperature for 45 min in the dark. The samples were acquired in flow cytometer (BD Inc., San Jose, CA) equipped with 488 nm 15 mW argon ion laser. The equipment was calibrated using PI labelled chicken RBC. Normal human peripheral blood lymphocytes were used to identify the normal diploid peak that served as reference peak for subsequent assays.

At least 10,000 events were collected for each sample using ‘Cell Quest’ software (Becton-Dickinson Inc., San Jose, CA). Acquisition program was set to collect DNA fluorescence signal as total area versus peak (signal height) in order to eliminate doublets and aggregates. Data were analyzed using ‘Modfit LT’ software (BD Inc., San Jose, CA). Mean co- efficient of variation of the measurements were within acceptable range (2-8%) in all the samples.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using STATA-7.0 (intercooled version) computer software (Stata Inc. Houston, TX, USA). Association of two categorical variables was assessed either by Chi square (χ2) test or Fishers’ Exact test as and when appropriate. P< 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

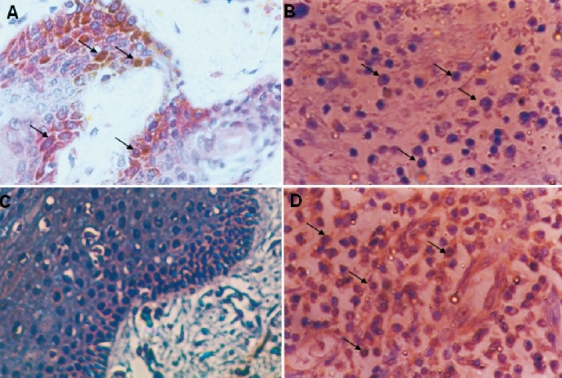

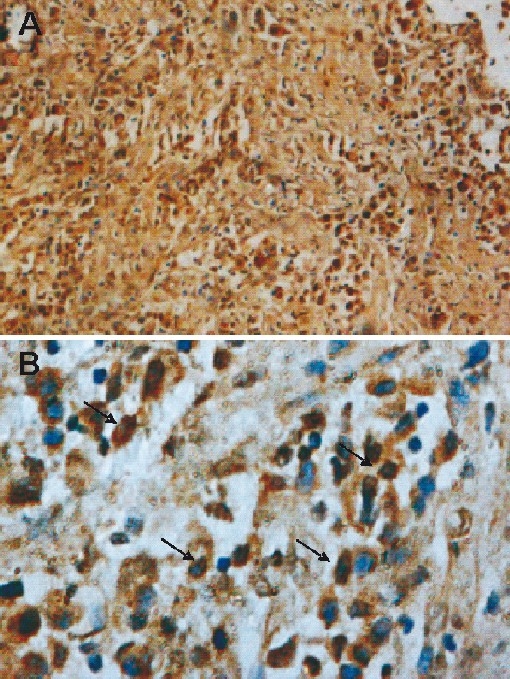

In this study Fas and FasL expression was evaluated in 41 patients with primary tobacco-related intra-oral carcinoma and associated the data with clincopathological feature and cell cycle parameters. Higher Fas receptor immunoreactivity was observed in all normal oral tissues (Fig. 1A), among patients low Fas immunoreactivity was observed in 2 of 41 (5%) cases (Fig. 1B). One patient showed higher Fas expression in tumour infiltrating lymphocytes but tumour cells per se were negative. Thus no further analysis was possible on Fas immunoreactivity with clinicopathological and cell cycle parameters. FasL expression in normal oral tissues and oral tumours has been shown in Fig. 1 (C D). FasL immunoreactivity was observed in 26 of 41 (63%) patients with primary tumours but not in the normal tissues. Further, in contrast to Fas, higher FasL staining was observed in most of the tumour area (Fig. 2A) that showed both membrane and cytoplasmic staining in tumour cells (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1.

Fas receptor and FasL immunoreactivity in normal oral mucosa and tobacco-related intraoral squamous cell carcinoma: A. Fas receptor immunoreactivity in normal oral mucosa showing high expression on the cell surface and in the cytoplasm (arrows). B. Faint Fas receptor expression on the cell surface in oral squamous cell carcinoma (arrows). C. Negative FasL immunoreactivity in normal oral mucosa E. High FasL expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma (arrows) (original magnifi cation ×400).

Fig. 2.

FasL immunoreactivity in tobacco-related intraoral squamous cell carcinoma: A. High FasL expression seen in whole tumour area (original magnifi cation X100). B. High expression of FasL is seen (arrows) on cells surface and in the cytoplasm (original magnification ×400).

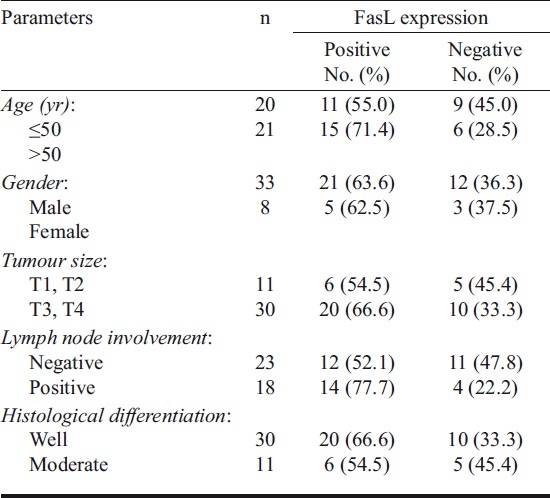

The association of FasL expression with clincopathological features has been presented in Table I. In this series, majority of patients were males (80%) with larger (T3/T4; 73%), node negative (56%) and well differentiated (73%) tumours. The composite late tumour stage was associated with higher FasL staining as compared to early stage tumours, although the values were statistically insignificant. FasL positive tumours were more frequent (71.4%) in patients with late onset (>50 yr) of the disease. Similarly, greater tumour size (T3, T4) and lymph node involvement was associated with higher FasL immunoreactivity as compared to the smaller (T1, T2) tumours. Furthermore, no significant difference was observed in FasL expression between well differentiated and moderately differentiated tumours.

Table I.

FasL expression in relation to clinicopathological features of oral cancer patients

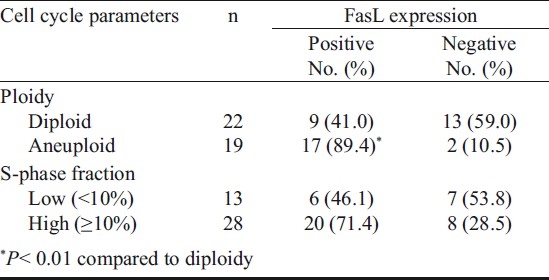

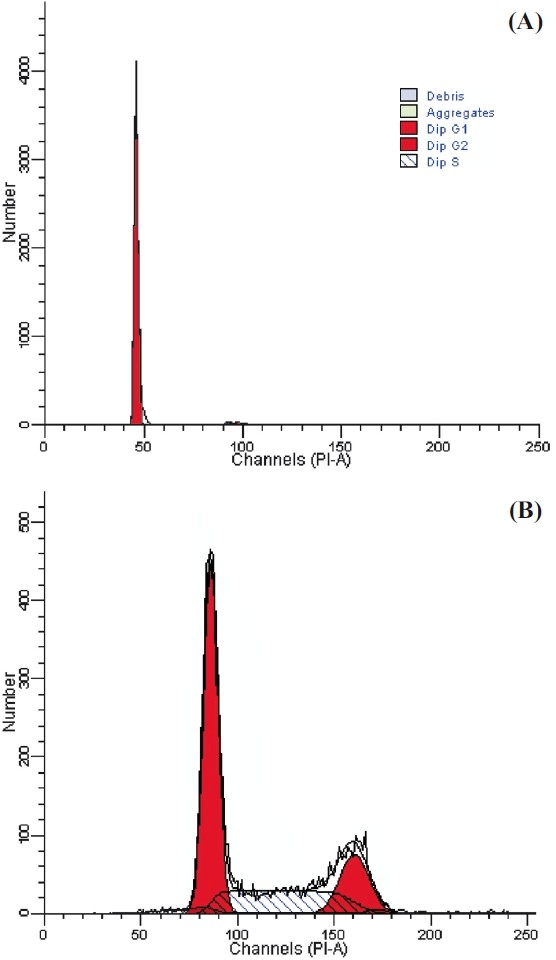

The association of FasL expression with cell cycle parameters is shown in Table II. The representative histogram of DNA ploidy is shown in Fig. 3. The DNA flow cytometry of primary tumours revealed diploidy in 22 (54%) and aneuploidy in 19 (45%), and 68 per cent of tumours showed higher (>10%) S-phase fraction (SPF). Analysis considering the most aggressive DNA pattern (aneuploidy) revealed significantly (P<0.01) higher frequency of FasL expression in aneuploid (89.4%) as compared to those with diploid (41%) tumours. Similarly, patients with higher SPF values showed higher frequency of FasL immunoreactivity (71.4%) as compared to those with lower SPF. It appears that FasL expression is related to the most aggressive DNA pattern such as aneuploidy and high SPF in patients with tobacco related intraoral squamous cell carcinoma.

Table II.

FasL expression in relation to cell cycle parameters of oral cancer patients

Fig. 3.

DNA histogram showing cell cycle fractions: A Normal cells; B Tumour cells.

Discussion

Apoptosis plays an important role in a variety of physiological processes and its disregulation contributes to many diseases including cancer15. Fas and FasL have been regarded as very important effectors of apoptosis in various biological conditions and its disregulated expression in a variety of carcinomas such as breast16 hepatocellular17, colorectal18 and nasopharyngeal19 carcinoma. Previously, it has been shown that squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and oral cavity, lung and oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines express Fas20. In contrast, in the present study Fas expression was seen only in 5 per cent of patients with tobacco-related intraoral carcinoma while majority of patients did not show Fas immunoreactivity. Similarly, Fas expression has been found to be heterogeneous and essentially absent in majority of patients with oesophageal carcinoma21 though it was expressed in the normal oesophageal squamous epithelium22. Suppression of Fas receptor has been shown to be negatively associated with tumour cell differentiation and apoptosis in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma23. The cause of Fas downregulation in cancer cells is still unknown. However, in case with oesophageal adenocarcinoma Fas downregulation was found not due to genetic defect or mRNA abnormality but possibly by post-translational modifications21,24. The downregulation or absence of Fas receptor in tumour cells has been considered as a primary mechanism for apoptotic resistance and insensitivity to treatments22,25.

In the present study, we observed FasL expression in 63 per cent of patients with primary tobacco-related oral squamous cell carcinoma. In addition, the expression of FasL was restricted to the tumour area only and not in the normal area of the same tissue or in the normal oral tissue samples. FasL immunoreactivity appeared to be associated with late onset and advanced stage tumours. In our study association between FasL expression and histological differentiation of tumour could not be established probably due to absence of poorly differentiated tumours in the series. Although there are not many reports on FasL expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma, a higher FasL expression has been reported in oral squamous cell carcinoma23 and other human malignancies such as lung26, oesophageal22, gastric27 and colorectal carcinoma18. Our results are further supported by earlier observations which demonstrated prevalent expression of FasL protein and mRNA in primary cancer cells and throughout the cancer progression6 and FasL was regarded as a common mediator of immune privilege status to the tumour cells6.

One of the important finding of the present study was that FasL expression in oral cancer patients showed a direct association with the aggressive DNA pattern. We observed intense FasL expression in almost 90 and 71 per cent patients with aneuploid tumours and with high S-phase fraction respectively. Thus it appears that FasL expression is associated with most aggressive DNA pattern in patients with tobacco-related intra oral squamous cell carcinoma. Fas and FasL system has been proposed to serve as a cellular proliferating mechanism18 and FasL expression as a precursor of human malignancies28. In addition, Fas and FasL system was found to be related to spontaneous apoptosis in a proportion of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) but not from the normal healthy donors29. It has been shown that FasL is involved at least in part, in activation of caspases in Fas+ T-lymphocytes and that the tumour associated FasL mediates apoptotic death of Fas bearing effector T-cells in the peripheral blood as well as tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with head and neck cancer29–31. Similarly, tumour cell-induced apoptosis was observed in Jurkat T-cells co-incubated with HNSCC cells. Such apoptotic cell death was found to be associated with the increasing ratio of tumour cells: lymphocytes and was inhibited by FasL neutralizing antibody32. Interestingly, the tumour-derived FasL-mediated apoptotic cell death was found to be differentially occurring in activated CD8+ T-cells33. FasL expressing cells become insensitive to apoptotic stimuli22 because these simultaneously acquire the capability to evade apoptotic pathway by over-expressing bcl-2 and/or Bax. Recently, Fas-FasL mediated apoptosis of CD8+ T-cells was found to be one of the mechanisms by which CD4+ CD25 high Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells (Treg) induces suppression of cell mediated immune response in HNSCC patients34. Thus FasL expression appears to be an acquired capability of tobacco-related oral carcinoma to evade immune-surveillance and may also be involved in the establishment, growth and dissemination of the tumour cells.

In conclusion, results of the present study suggest that downregulation of Fas receptor and upregulation of FasL is an important feature of tobacco-related intraoral squamous cell carcinoma. FasL expression was associated with advanced clinical stage and the aggressive DNA pattern. These tumours appear to not only escape Fas-mediated apoptosis by downregulation of the expression of Fas receptor, but may have ability to actively kill Fas bearing tumour infiltrating lymphocytes by constitutive expression of FasL. Thus Fas and FasL system may be an important prognostic variable in patients with tobacco-related intraoral squamous cell carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi. The second author (PK) was recipient of the research fellowship from DBT under Post-MD/MS training program.

References

- 1.Cheng J, Liu C, Koopman WJ, Mountz JD. Characterization of human Fas gene. Exon/intron organization and promoter region. J Immunol. 1995;154:1239–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suda T, Takahashi T, Golstein P, Nagata S. Molecular cloning and expression of the Fas ligand, a novel member of the tumor necrosis factor family. Cell. 1993;75:1169–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90326-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boldin MP, Goncharov TM, Goltsev YV, Wallach D. Involvement of MACH, a novel MORT 1/FADD – interacting protease, in Fas/APO1-and TNF-receptor-induced cell death. Cell. 1996;85:803–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muschen M, Warskulat U, Beckmann MW. Defining CD95 as a tumor suppressor gene. J Mol Med. 2000;78:312–25. doi: 10.1007/s001090000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahne M, Rimoldi D, Schroter M, Romero P, Schreier M, French LE, et al. Melanoma – cell expression of Fas (Apo-1/CD95) ligand: implications for tumor immune escape. Science. 1996;274:1363–6. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connell J, O’Sullivan GC, Collins JK, Shanahan F. The Fas counterattack: Fas-mediated T-cell killing by colon cancer cells expressing Fas ligand. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1075–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichmann E. The biological role of the Fas/FasL system during tumour formation and progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:309–15. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biennial Report, National Cancer Registry Programme 1988-89. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 1992. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna NN, Srivastava PK, Khanna S, Das SN. Intensive combination chemotherapy for cancer of the oral cavity. Cancer. 1983;52:790–3. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830901)52:5<790::aid-cncr2820520506>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawhney M, Mathew M, Valarmathi MT, Das SN. Age related changes in Fas (CD95) and Fas ligand gene expression and cytokine profiles in healthy Indians. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2006;24:47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manchanda P, Sharma SC, Das SN. Differential regulation of IL-2 and IL-4 in patients with tobacco related oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2006;12:455–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das SN, Khare P, Patil A, Pandey RM, Singh MK, Shukla NK. Association of DNA pattern of metastatic lymph node with disease free survival in patients with intraoral squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:216–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manual for staging of cancer. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott; 1998. American Joint Committee on Cancer; pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hood DL, Petras RE, Edinger M, Fazio V, Tubbs RR. Deoxyribonucleic acid ploidy and cell cycle analysis of colorectal carcinoma by flow cytometry.A prospective study of 137 cases using fresh whole cell suspensions. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93:615–20. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/93.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerr JF, Winterford CM, Harmon BV. Apoptosis. Its significance in cancer and cancer therapy. Cancer. 1994;73:2015–26. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940415)73:8<2013::aid-cncr2820730802>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullauer L, Mosberger I, Grusch M, Rudas M, Chott A. Fas ligand is expressed in normal breast epithelial cells and is frequently up regulated in breast cancer. J Pathol. 2000;190:20–30. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200001)190:1<20::AID-PATH497>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuzawa K, Takahashi K, Furuta K, Tagaya T, Ishikawa T, Wada K, et al. Expression of Fas/Fas Ligand and its involvement in infiltrating lymphocytes in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:681–8. doi: 10.1007/s005350170031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimoyama M, Kanda T, Liu L, Koyama Y, Suda T, Sakai Y, et al. Expression of Fas ligand is an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis. J Surg Oncol. 2001;76:63–8. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200101)76:1<63::aid-jso1011>3.0.co;2-c. discussion 69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdulkarim B, Sabri S, Deutsch E, Vaganay S, Marangoni E, Vainchenker W, et al. Radiation-induced expression of functional Fas ligand in EBV-positive human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:229–37. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000415)86:2<229::aid-ijc12>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundelin K, Jadner M, Norberg-Spaak L, Davidsson A, Hellquist HB. Metallothionein and Fas (CD95) are expressed in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1860–4. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Younes M, Schwartz MR, Finnie D, Younes A. Over expression of Fas ligand (FasL) during malignant transformation in the large bowel and in Barrette's metaplasia of the esophagus. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1309–13. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gratas C, Tohma Y, Barnas C, Taniere P, Hainaut P, Ohgaki H. Up-regulation of Fas (APO-1/CD95) ligand and down-regulation of Fas expression by human esophageal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2057–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loro LL, Vintermyr OK, Johannessen AC, Liavaag PG, Jonsson R. Suppression of Fas receptor and negative correlation of Fas ligand with differentiation and apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:82–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huges SJ, Nambu Y, Soldes OS, Hamstra D, Rehemtulla A, Iannettoni MD, et al. Fas/APO-1 (CD95) is not translocated to the cell membrane in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5571–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nambu Y, Hughes SJ, Rehemtulla A, Hamstra D, Orringer MB, Beer DG. Lack of cell surface Fas/APO-1 expression in pulmonary adenocarcinomas. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1102–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niehans GA, Brunner T, Frizelle SP, Liston JC, Salerno CT, Knapp DJ, et al. Human lung carcinomas express Fas ligand. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1007–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett MW, O’Connell J, O’ Sullivan GC, Brady C, Roche D, Collins JK, et al. The Fas counterattack in vivo: apoptotic depletion of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes associated with Fas ligand expression by human esophageal carcinoma. J Immunol. 1998;160:5669–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill LL, Ouhtit A, Loughlin SM, Kripke ML, Ananthaswamy HN, Owen-Schaub LB. Fas ligand: a sensor for DNA damage critical in skin cancer etiology. Science. 1999;285:898–900. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann TK, Dworacki G, Tsukihiro T, Meidenbauer N, Gooding W, Johnson JT, et al. Spontaneous apoptosis of circulating T lymphocytes in patients with head and neck cancer and its clinical importance. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2553–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JW, Wieckowski E, Taylor DD, Reichert TE, Watkins S, Whiteside TL. Fas ligand-positive membranous vesicles isolated from sera of patients with oral cancer induce apoptosis of activated T lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1010–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whiteside TL. The role of death receptor ligands in shaping tumor microenvironment. Immunol Invest. 2007;36:25–46. doi: 10.1080/08820130600991893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gastman BR, Atarshi Y, Reichert TE, Saito T, Balkir L, Rabinowich H, et al. Fas ligand is expressed on human squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck, and it promotes apoptosis of T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5356–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergmann C, Strauss L, Wieckowski E, Czystowska M, Albers A, Wang Y, et al. Tumor-derived microvesicles in sera of patients with head and neck cancer and their role in tumor progression. Head Neck. 2009;31:371–80. doi: 10.1002/hed.20968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strauss L, Bergmann C, Whiteside TL. Human circulating CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ regulatory T cells kill autologous CD8+ but not CD4+ responder cells by Fas –mediated apoptosis. J Immunol. 2009;182:1469–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]