Abstract

Background & objectives:

Chronic cough and chronic phlegm are important indicators of respiratory morbidity, accelerated lung function decline, increased hospitalization and mortality. This study was planned to estimate the prevalence of chronic cough and phlegm in the absence of dyspneoa and wheezing and to study its associated factors in a representative population of Mysore district.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was planned in a representative population of Mysore taluk. Eight villages were randomly selected based on the list of villages from census 2001. Trained field workers using the Burden of Obstructive Diseases questionnaire carried out a house-to-house survey.

Results:

A total of 4333 adult subjects were enrolled in the study with 2333 males and 2000 females. The prevalence of chronic cough in the community was 2.5 per cent and that of chronic phlegm was 1.2 per cent. A significant association was observed between chronic cough and age, gender, occupation and smoking and chronic phlegm with age, gender, occupation, indoor animals and smoking. A multivariate analysis confirmed independent association of age, occupation and smoking for chronic cough and age and smoking for chronic phlegm. On sub-group analysis of males, heavy smokers had higher prevalence of chronic cough and chronic phlegm as compared to light smokers and non smokers.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The prevalence of chronic cough was 2.5 per cent and chronic phlegm was 1.2 per cent in the general population in Mysore which is lower than that observed in other studies. Heavy smoking was an important preventable risk factor identified in this study and efforts towards smoking cessation are crucial to achieve good respiratory health in the community.

Keywords: Chronic cough, chronic phlegm, prevalence, tobacco smoking

Prevalence of chronic cough and phlegm are important indicators of respiratory morbidity in the community1. These have assumed importance ever since epidemiological studies have shown significant association of these symptoms with mortality due to respiratory diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)2,3. These have also been shown to be associated with accelerated lung function decline4,5 and increased risk of hospitalization and utilization of health services5. It remains to be proven however, whether chronic respiratory symptoms precede COPD and offers a window period when interventions could prevent disease progression. Long-term follow up studies have shown conflicting results leading to the GOLD guidelines6 to remove stage 0 or “at risk” population which included subjects with chronic cough and phlegm with normal lung functions. A retrospective analysis in the Copenhagen City Heart Study did not find any association with the presence of chronic cough and phlegm with the prevalence of COPD5. However, two long-term prospective follow up studies, which used incident cases of COPD as an outcome, found a significant association between chronic respiratory symptoms like chronic cough and phlegm and COPD7,8. These studies concluded that the presence of chronic cough and chronic phlegm is an early marker of COPD in a non-ignorable proportion of patients, independent of smoking habits, and in clinical practice, the persistence of chronic symptoms should be accurately investigated. Chronic cough and phlegm in India would include not only COPD, but also common conditions like chronic asthma, tuberculosis, and bronchiectasis among others. Data on prevalence of chronic cough and phlegm in India are sparse especially in the rural population, where environmental factors are different compared to the urban areas.

Globally, respiratory diseases are set to occupy the third most common cause of death and the fifth most common cause of disability by 20209. In India, chronic respiratory disease was estimated to account for 7 per cent of all deaths and 3 per cent of DALY′S lost10. Tobacco smoking is observed to be the most important risk factor associated with chronic respiratory morbidity11. Environmental tobacco smoke12 and exposure to biomass fuels13,14 are other important risk factors especially in women and children. The major objectives of the present study were to estimate the prevalence of chronic cough and phlegm in the absence of dyspneoa and wheezing and to study its associated factors in a representative population of Mysore district, Karnataka, in south India.

Material & Methods

Study design and subjects: The cross-sectional survey to estimate the prevalence of COPD was done in a representative population in Mysore district. A representative sample was drawn from the rural areas of Mysore district. A two stage sampling design was adopted. In the first stage, taluks were selected at random and in the second stage villages were randomly selected from the list of all the villages in the selected taluks and the entire village was covered. In the first stage, two out of five taluks in Mysore district, Mysore taluk and Nanjangud taluk were selected.

The sample size for the study was estimated utilizing the available information on the prevalence of COPD in India. It was observed in the earlier studies11,15 that the prevalence estimates was around 5 per cent among adults more than 40 yr of age. Since many smokers start in their teens, it was decided to include adults above the age of 30 yr to assess the prevalence of chronic cough and phlegm in younger adults. Thus with a 5 per cent prevalence with 10 per cent error on the estimate, the sample size for the study was calculated to be 8000 adults. The sampling unit of the study was “household” and all the eligible persons in the households were included in the study. Since nearly 25-30 per cent of the population was above 30 yr of age, a total of 32,000 individuals were required to be covered to identify 8000 eligible subjects for the study. With an average village size of 2000, 16 villages needed to be covered. A total of 16 villages were thus randomly selected, 8 villages in each taluka from the list of all villages according to the census 2001. The present study on the prevalence of chronic cough and phlegm was a sub-study of the prevalence of COPD and the study included 4333 subjects from 8 selected villages from Mysore taluka. All the subjects in these 8 selected villages above the age of 30 yr were included in the present study.

Methodology: The total duration of the study was 3 years (June 2006-May2009). The data collection for the Mysore taluka was completed in 12 months. The 4333 study subjects were a random representative selection of the general population in Mysore taluka. Trained field workers collected information after a house-to-house visit. The questionnaire used was a validated instrument used in “The Burden of Obstructive Lung Diseases” study16. The questionnaire was translated into the local language according to standard procedures for translation and back-translation and pilot tested in the population studied. The questionnaire was read out to the patient in exactly the same order as listed in the questionnaire and sufficient time was given to the patient to respond to the questions. If the patient did not understand the questions, it was repeated. If the patient still was doubtful about the answer, it was recorded as “No”. The survey was conducted both in the morning and evening to ensure compliance. The field workers visited all the houses in the selected villages. Where houses were locked, no information could be obtained. In other houses, there were non-responders due to non availability of the eligible subject or refusal. The houses were visited at least on three occasions before declaring them as “non-responders” or “locked houses”.

Cases were identified on the basis of a positive response to the questions: (i) Do you usually cough when you do not have a cold?; (ii) Are there months in which you cough on most days? and (iii) Do you cough on most days for as much as three months each year?

Similar questions were asked about phlegm. Chronic respiratory symptoms were defined according to standard Medical Research Council definition17. “Chronic cough” being cough first thing in the morning or at any time during the day or night for as much as three months each year and “chronic phlegm” is the production of phlegm from the chest first thing in the morning or at any time during the day or night for as much as three months each year.

The smoking habit was classified as current smokers, past smokers or non smokers. Non smokers were defined as subjects who have never smoked. Past smokers were defined as subjects who have stopped smoking for at least 1 year and current smokers were defined as subjects who continue to smoke7. Based on pack years of smoking18 they were classified as light smokers (0-14 pack years) or moderate-heavy smokers (> 14 pack years). The major types of drinking water facility in the villages were tap, well, bore well or pond. Indoor animals present were defined as animals kept within the house other than pets, such as cows, buffaloes, sheep, goats and hens.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the JSS Medical College, Mysore.

Statistical analysis: The data analysis was carried out utilizing EPIINFO 8 and SPSS version 13 to estimate the prevalence of chronic cough and phlegm and also to evaluate the significant association of the factors considered in the study. For each of the variables, which were of categorical nature, such as, age, occupation and education, the dummy variable approach, was used to derive the odds ratios. The dummy variables were prepared considering each of the classification within the variable as a separate ‘risk factor’ and the remaining subjects as ‘no risk factor’. The multivariate analysis was also carried out to study the independent association of the factors, which were observed to be significant in the univariate analysis.

Results

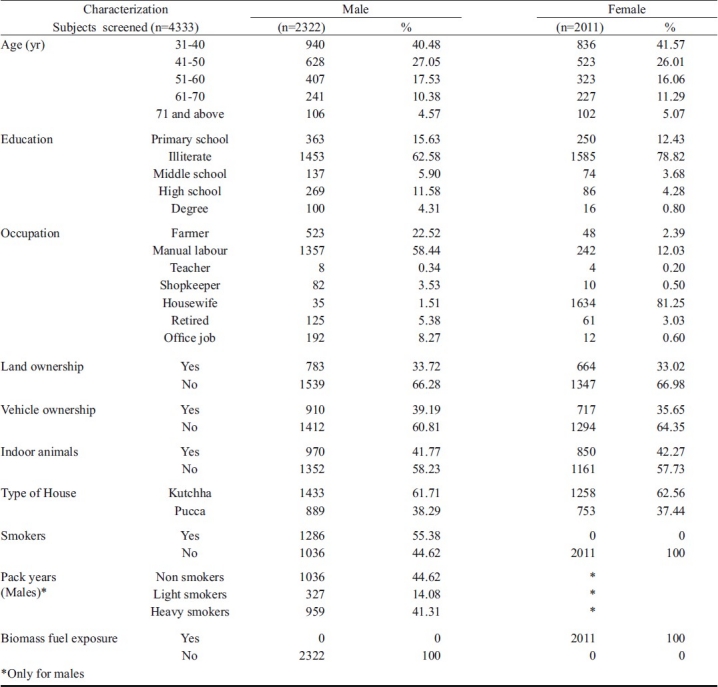

A total of 4333 subjects were screened in Mysore taluk. The gender distribution constituted 2322 (53.59%) males and 2011 (46.41%) females. The individual non-responder rate was 137 (3.16%). The number of houses with locked doors was 7.54 per cent. Demographic features of the population are presented in Table I. Most of the population in the rural areas of Mysore district were illiterate 3038 (70%), manual labour was the most common occupation 1356 (58.4%) in males and majority of women were housewives 1633 (81.2%). Nearly 33.4 per cent of the population owned land and 1627 (37%) owned vehicles. Forty two per cent (1028) of the population had indoor animals other than pets, 2691 (62%) lived in kuccha houses and 3719 (85.8%) had drinking water supply from the Gram panchayat. The other important source of drinking water supply was bore wells 599 (13.8%). Only a few families had drinking water source from wells 13 (0.3%) and ponds 2 (0.06%). More than half the males in the population smoked 1286 (55.38%). There were only 38 ex-smokers. Most of the smokers smoked beedis. The mean pack years smoked was 23.02 (SD 17.17). Among smokers, heavy smokers were the most common 959 (74.5%) and the remaining were light smokers. Most of the women were exposed to biomass fuels on a regular basis 2011 (100%).

Table I.

Socio demographic characterisation of the persons included in the study

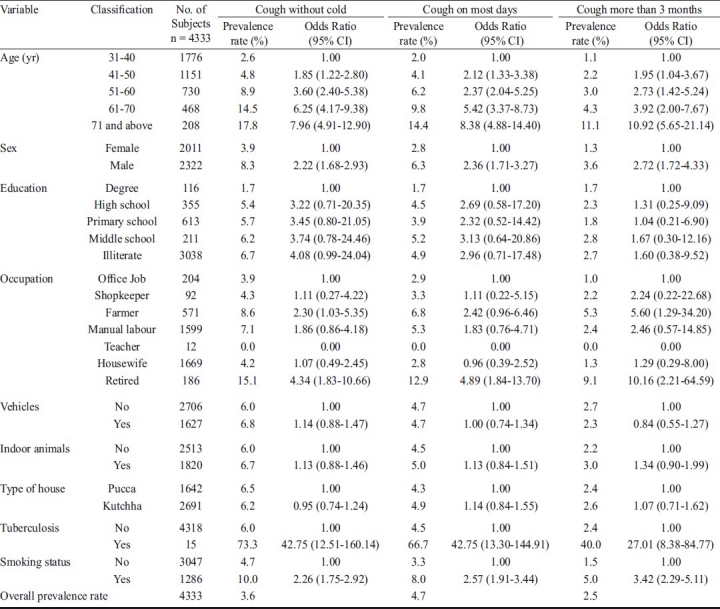

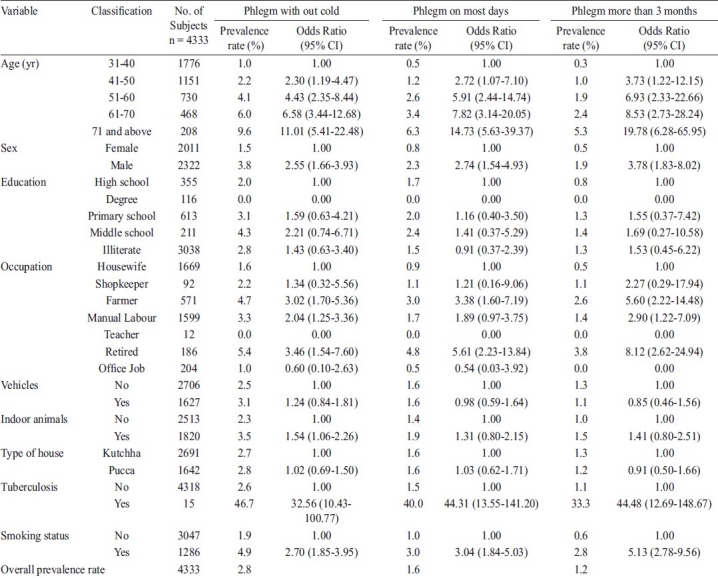

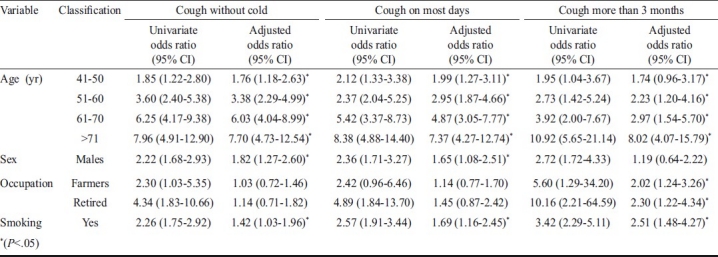

The prevalence of chronic cough in the population studied was 2.5 per cent and the prevalence of chronic phlegm was 1.2 per cent. The prevalence of cough when not having a cold, cough on most days of a month and the prevalence of chronic cough and their associated factors are presented in Table II. The prevalence of phlegm from the chest when not having cold, phlegm on most days of a month and the prevalence of chronic phlegm and their associated factors are presented in Table III.

Table II.

Factors associated with cough without a cold, cough on most days and cough for more than 3 months in Mysore Taluk

Table III.

Factors associated with phlegm without a cold, phlegm on most days and phlegm for more than 3 months in Mysore Taluk

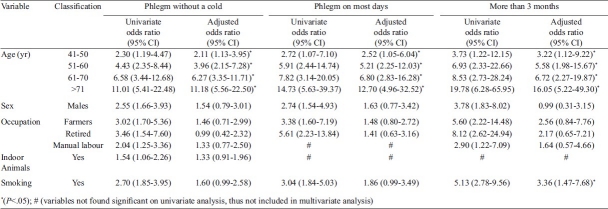

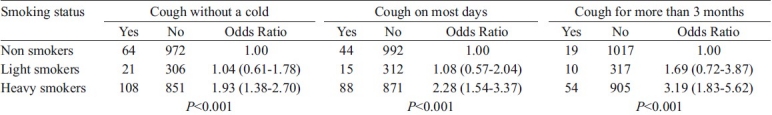

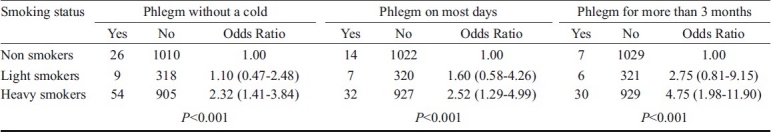

The logistic regression analysis was carried out to study the independent factors associated with all the six dependent variables such as cough without a cold, cough on most days and cough for three months (Table IV), phlegm without a cold, phlegm on most days and phlegm for thee months (Table V), utilizing the factors which were significant in the univariate analysis. Independent association with cough without a cold was observed for age, gender and smoking, but not for occupation. The older age groups starting from 41 years had higher risk and there was an increasing trend in the odds ratio. Similar factors were found to be significantly associated with cough on most days. In subjects with chronic cough, significant association was observed with age, smoking and occupation (farmers and retired). In both phlegm without cold, and phlegm on most days, independent association was observed for increasing age but not for other variables significantly associated in univariate analysis. In subjects with chronic phlegm, increasing age and smoking was found to have a significant association. Smoking was significantly associated with cough and phlegm and a significant association was observed for all the variables of cough and phlegm for heavy smokers (Tables Table VI & VII). Regular use of biomass fuels was noted in all women and no statistical tests could, therefore, be performed.

Table IV.

Factors associated with cough without a cold, cough on most days and cough more than 3 months

Table V.

Factors associated phlegm without a cold, phlegm on most days and phlegm for more than 3 months

Table VI.

Dose response trend of cough without a cold, cough on most days and cough for more than 3 months with pack years of smoking among males

Table VII.

Dose response trend of phlegm without a cold, phlegm on most days and phlegm for more than 3 months with pack years of smoking among males

Discussion

The prevalence of chronic cough and chronic phlegm, are important indicators of respiratory morbidity and mortality. These symptoms were associated with an accelerated decline in lung function4, increased hospitalization5 and an increased all cause mortality2. An important concern was the findings of a longitudinal study in 5,002 young adults aged 20 to 44 yr by de Marco et al8 which followed the subjects for a median of 8.9 yr for incident COPD, which showed that a substantial number of young subjects with chronic cough and chronic phlegm developed COPD and that the presence of chronic cough and phlegm almost doubled the risk of COPD after adjusting for risk factors for this disease. In another longitudinal study by Lindberg et al7 respiratory symptoms were found to be significantly associated with incident COPD in both men and women.

The present study evaluates the prevalence of chronic cough and phlegm in the general population and its associated factors in the rural Mysore taluka. The prevalence of chronic cough in the rural population was found to be 2.5 per cent and that of chronic phlegm was 1.2 per cent, which was less than that reported in other studies. Different studies in the western world have analyzed different age groups depending on whether their emphasis is on asthma or COPD and the prevalence of chronic cough varied from 2.9 to 32 per cent and that of chronic phlegm varied from 3.1 to 31 per cent18–20. In many studies8,18,19 the prevalence of chronic phlegm was more than or equal to the prevalence of chronic cough unlike in our study, where many patients with chronic cough did not have chronic phlegm. There are only a few studies that have evaluated the prevalence of cough and phlegm in India. The prevalence of cough was found to be between 2.4 and 5.6 per cent in the rural areas and 1.7 to 5.4 per cent in the urban areas in different centers in India21. The prevalence of phlegm in the same study was 1.9 to 4.4 per cent in the rural areas and 2 to 4.4 per cent in the urban areas. In another study by Gupta et al22 the prevalence of cough was 2.2 per cent and phlegm 2 per cent in subjects living in houses without environmental tobacco smoke exposure and cough was 2.6 per cent and phlegm was 2.2 per cent in houses with environmental tobacco exposure. The operational definitions used for cough and phlegm in these studies was different from our study, which may account for the higher prevalence of the above symptoms in these studies. The operational definition for cough and phlegm used in these two studies were “cough at night”, “cough in the morning” and “phlegm in the morning”, whereas the present study used cough and phlegm “without a cold”, “on most days” and “for at least 3 months”.

Increasing age was found to be an important factor associated with chronic cough and chronic phlegm in our study, probably reflecting a higher prevalence of diseases associated with chronic cough and chronic phlegm like COPD and chronic asthma and also a longer duration of exposure to risk factors like smoking and biomass fuels. The prevalence of chronic cough of 11.1 per cent seen in subjects above 70 years was similar to the prevalence observed in most other studies20,23 that included subjects above 65 years. Even in this subgroup of elderly subjects, the prevalence of chronic phlegm noted in our study was much less than the prevalence previously observed. Studies in the young adults (20-44 yr) have demonstrated a prevalence of chronic cough around 11 per cent18 while the prevalence of chronic cough in young adults in our study was 1.1 per cent and chronic phlegm was 0.3 per cent, probably reflecting a lower prevalence of chronic allergic diseases which are contributory for chronic cough and phlegm in this age group in the rural areas.

Males had an increased risk of suffering from chronic cough (3.6 versus 1.3%) and chronic phlegm (1.9 versus 0.5%) than females. This observation is consistent with other studies24 and is probably related to the increased prevalence of smoking among males in India. In the West, where a significant prevalence of smoking among females is present, an equal or even higher prevalence of these respiratory symptoms have been reported in women25.

When subgroup analysis was carried out for males, heavy smoking was found to be an important association identified in this study both for chronic cough and chronic phlegm. Both light and heavy smokers had a higher prevalence of chronic cough than non smokers, and a dose response relationship was observed. Similar association was observed for prevalence of chronic phlegm as well; with light smokers and heavy smokers having higher prevalence than nonsmokers and a dose response relationship was observed. Previous studies21,22,26 have demonstrated that smoking is indeed a major risk factor for chronic respiratory diseases and symptoms. Dose-response relationship has been observed in these studies and beedi smoking was associated with higher respiratory symptoms than cigarette smoking26. The prevalence of smoking in our rural male population was 55.38 per cent, higher than other studies in India21,26.

Exposure to biomass fuels was present in all women and, therefore, statistical analysis could not be performed. It was interesting to note that the prevalence of chronic cough and chronic phlegm among women were similar to non smoking men.

On univariate analysis a significant association was observed with chronic cough for farmers and retired subjects, and on multivariate analysis, an independent association was also observed. The association of chronic cough with retired subjects was independent of age and the prevalence of smoking among retired subjects was less than the smoking prevalence in this rural population. It would be useful in future studies to evaluate the previous occupations of these retired subjects. On univariate analysis, a significant association with chronic phlegm was observed for farmers, manual labourers and retired subjects. Multivariate analysis did not reveal an independent association for any occupation.

Similar associations were found for cough and phlegm without a cold and for cough and phlegm on most days of a month, which had a much higher prevalence than that of chronic cough and chronic phlegm. The cases with cough and phlegm without a cold could progress to cases with chronic cough and chronic phlegm in the future.

The strengths of our study were its large sample size, good study design, and good sampling strategy in identifying a representative population in the rural areas of Mysore district. Our study has important clinical implications. Chronic cough and chronic phlegm are important indicators of respiratory health in the general community. Data of our study have highlighted some interesting results. The prevalence of smoking among adult males in rural Mysore taluk was much higher as compared to other studies in rural adults in India20. However, the prevalence of chronic cough and chronic phlegm was low in our study population compared to the burden of smoking. Prevalence of chronic cough in heavy smokers (>14 pack yr) in a study of urban adults in Delhi26 was 67.4 per cent and chronic phlegm was 67.2 per cent compared to 5.63 and 3.12 per cent respectively among heavy smokers in our study population. The factors related to this low prevalence needs further study to examine whether this is related to a difference in inhalation practices of smoking like absence of deep inhalation of tobacco smoke as compared to subjects in other studies, difference in nutrition, other environmental or genetic factors or other protective factors prevalent in our population including better anti-oxidant defenses. There is a need for multicentric studies to evaluate the above-mentioned factors in a systematic and standardized method to throw more light on this observation.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that the prevalence of chronic cough and chronic phlegm were 2.5 and 1.2 per cent respectively, in the rural areas of Mysore district. The study observed a decreasing trend from cough and phlegm without a cold, to chronic cough and phlegm. There is a need for studies to identify the various diseases responsible for chronic cough and chronic phlegm in the community and determine measures which could help in preventing the cases with cough and phlegm without a cold into progressing into chronic cough and chronic phlegm. Heavy smoking was an important preventable risk factor identified in this study and efforts towards smoking cessation are crucial to achieve good respiratory health in the community.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research for financial support [ICMR Grant No. 5/8/4-4 (Env)/2003-NCD-I] and Dr Sonia Buist, BOLD executive committee for permission to use the BOLD questionnaire. Authors thank JSS Mahavidyapeetha, Principal, JSS Medical College and Medical Superintendent, JSS Hospital for the support in conducting the study.

References

- 1.Annesi I, Kauffmann F. Is respiratory mucus hypersecretion really an innocent disorder. A 22-year mortality survey of 1,061 working men? Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:688–93. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.4.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lange P, Nyboe J, Appleyard M, Jensen G, Schnohr P. Relation of ventilatory impairment and of chronic mucus hypersecretion to mortality from obstructive lung disease and from all causes. Thorax. 1990;45:579–85. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.8.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speizer FE, Fay ME, Dockery DW, Ferris BG., Jr Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality in six U.S. cities. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:S49–55. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3_Pt_2.S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman CB, Xu X, Speizer FE, Ferris BG, Jr, Weiss ST, Dockery DW. Longitudinal lung function decline in subjects with respiratory symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:855–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P. Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1530–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindberg A, Jonsson AC, Ronmark E, Lundgren R, Larsson LG, Lundback B. Ten-year cumulative incidence of COPD and risk factors for incident disease in a symptomatic cohort. Chest. 2005;127:1544–52. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Marco R, Accordini S, Cerveri I, Corsico A, Anto JM, Kunzli N, et al. Incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort of young adults according to the presence of chronic cough and phlegm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:32–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-381OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinath Reddy K, Shah B, Varghese C, Ramadoss A. Responding to the threat of chronic diseases in India. Lancet. 2005;366:1744–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jindal SK. Emergence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an epidemic in India. Indian J Med Res. 2006;124:619–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaakkola MS. Environmental tobacco smoke and health in the elderly. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:172–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00270702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brundtland GH. Health and the World Conference on Sustainable Development. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orozco-Levi M, Garcia-Aymerich J, Villar J, Ramirez-Sarmiento A, Anto JM, Gea J. Wood smoke exposure and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:542–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00052705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jindal SK, Aggarwal AN, Chaudhry K, Chhabra SK, D’Souza GA, Gupta D, et al. A multicentric study on epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its relationship with tobacco smoking and environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, Chen P, Kang J, Huang S, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:753–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1749OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Defi nition and classifi cation of chronic bronchitis for clinical and epidemiological purposes. A report to the Medical Research Council by their Committee on the Aetiology of Chronic Bronchitis. Lancet. 1965;1:775–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerveri I, Accordini S, Corsico A, Zoia MC, Carrozzi L, Cazzoletti L, et al. Chronic cough and phlegm in young adults. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:413–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00121103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vestbo J. Chronic cough and phlegm in young adults: should we worry? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:2–3. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1458ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enright PL, Kronmal RA, Higgins MW, Schenker MB, Haponik EF. Prevalence and correlates of respiratory symptoms and disease in the elderly. Cardiovascular Health Study. Chest. 1994;106:827–34. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.3.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aggarwal AN, Chaudhry K, Chhabra SK, D’Souza GA, Gupta D, Jindal SK, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for bronchial asthma in Indian adults: a multicentre study. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Chaudhry K, Chhabra SK, D’Souza GA, Jindal SK, et al. Household environmental tobacco smoke exposure, respiratory symptoms and asthma in non-smoker adults: a multicentric population study from India. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:31–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundback B, Nystrom L, Rosenhall L, Stjernberg N. Obstructive lung disease in northern Sweden: respiratory symptoms assessed in a postal survey. Eur Respir J. 1991;4:257–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pena VS, Miravitlles M, Gabriel R, Jimenez-Ruiz CA, Villasante C, Masa JF, et al. Geographic variations in prevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD: results of the IBERPOC multicentre epidemiological study. Chest. 2000;118:981–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.4.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anto JM, Vermeire P, Vestbo J, Sunyer J. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:982–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17509820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chhabra SK, Rajpal S, Gupta R. Patterns of smoking in Delhi and comparison of chronic respiratory morbidity among beedi and cigarette smokers. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2001;43:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]