Abstract

Canonical β-catenin-mediated Wnt signaling is essential for the induction of nephron development. Noncanonical Wnt/planar cell polarity (PCP) pathways contribute to processes such as cell polarization and cytoskeletal modulation in several tissues. Although PCP components likely establish the plane of polarization in kidney tubulogenesis, whether PCP effectors directly modulate the actin cytoskeleton in tubulogenesis is unknown. Here, we investigated the roles of Wnt PCP components in cytoskeletal assembly during kidney tubule morphogenesis in Xenopus laevis and zebrafish. We found that during tubulogenesis, the developing pronephric anlagen expresses Daam1 and its interacting Rho-GEF (WGEF), which compose one PCP/noncanonical Wnt pathway branch. Knockdown of Daam1 resulted in reduced expression of late pronephric epithelial markers with no apparent effect upon early markers of patterning and determination. Inhibiting various points in the Daam1 signaling pathway significantly reduced pronephric tubulogenesis. These data indicate that pronephric tubulogenesis requires the Daam1/WGEF/Rho PCP pathway.

Multiple organs including the kidney, lung, mammary gland, gut, heart, and ear are composed of tubule networks, the formation of which requires Wnt signaling. Several of these systems utilize canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling at early inductive stages followed by downregulation at later developmental time points.1–7 Noncanonical Wnt signals in turn regulate later tubulogenesis processes, including the polarized migration of branching cells.8–16 As learned from studies in varied organ systems, the Wnt pathways appear to exhibit key roles in tube formation.17–29

The kidney is an essential organ that functions in filtering wastes, absorbing nutrients and water, and maintaining body fluid osmolarity. The kidney develops from the intermediate mesoderm and undergoes inductive events promoting mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition to form the epithelial tubules of the nephron, the basic unit of filtration.30 Such nephric tubules serve not only as conduits for fluid flow within the kidney but also as a filtration device for selective absorption and excretion.

Three progressive developmental stages characterize mammalian kidney formation, resulting in the pronephros, mesonephros, and ultimately the adult kidney—the metanephros.31 On the other hand, amphibian and fish kidneys transition only once, from the pronephric (embryonic) to the mesonephric (adult) stage. Formation of the mesonephros (and metanephros in mammals) requires the preceding formation of the pronephros,32,33 and nephrons within each distinct stage form as a consequence of similar molecular events, thereby producing analogous tubular morphologies.34–37 From an experimental perspective, the pronephros, which contains a single nephron, offers a simplified system that mirrors events of mesonephric and metanephric nephron formation.34,38

Multiple signals contribute to nephron formation, including those of the fibroblast growth factor, bone morphogenic protein, and Wnt pathways.31,39,40 Numerous Wnt ligands are expressed in the developing kidney, including Wnt2, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt6, Wnt7b, Wnt8, Wnt9a, Wnt9b, Wnt11, and Wnt11b,41–48 and several of these are required for nephrogenesis. Although the downstream signaling trajectories for several of these Wnt ligands have been identified, many within the context of kidney development remain unclear. Wnt ligands may activate the canonical trajectory, defined as occurring through β-catenin, and/or they may activate noncanonical trajectories involving planar cell polarity (PCP), calcium signaling components, or other constituents. Although practical considerations generally constrain investigators to address one or two trajectories within a single study, it is now thought that each Wnt ligand is likely to activate several trajectories in context-dependent manners and even within a single context to activate multiple networked trajectories (exhibiting crosstalk).49

Wnt4 and Wnt9b are required for tubulogenesis within the metanephric mesenchyme in mice and initially act predominantly via canonical/β-catenin signaling.1,41,45 However, attempts to rescue Wnt4 and Wnt9b knockouts with β-catenin in explants of mouse kidney resulted in partial success, permitting metanephric mesenchyme condensation, but failed tubulogenesis.1 Furthermore, the overexpression of β-catenin in developing mouse or frog kidneys reduces tubule epithelialization.1,2 These studies suggested that canonical Wnt signals arise downstream of Wnt4 and Wnt9b, but must subsequently be attenuated for proper tube formation.1,50 Indeed, recent studies provide tantalizing evidence that noncanonical Wnt signals attenuate canonical Wnt signals to promote tubulogenesis.9,14,15

Several noncanonical Wnt components of the PCP pathway are implicated in kidney tubulogenesis, and disruption of these components is linked to morphogenesis defects leading to cystic kidney diseases.51 Mouse kidneys with hypomorphic Wnt9b expression in collecting duct stalks exhibit cystic phenotypes and deficient tubulogenesis, consistent with reduced Rho and JNK activation and the misorientation of cell divisions within developing nephric tubules.9 Vertebrate Inversin, a ciliary protein disrupted in nephronophthisis II cystic kidney disease and homologous with the Drosophila PCP component Diego, has been likened in zebrafish to a molecular switch between canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling.15 Mutations in seahorse, the zebrafish protein product of which interacts with Inversin and Dishevelled, likewise result in cystic kidneys,14 whereas Vangl2, homologous to Drosophila PCP component Van Gogh, regulates the posterior tilt of primary cilia within the zebrafish pronephric duct.10 In nonkidney mucociliary epithelia, Dishevelled's DEP and PDZ domains, which each contribute to noncanonical Wnt signaling, respectively participate in ciliogenesis or cilia orientation.52 Finally, loss of the fat4 protocadherin in mice, which in Drosophila is needed to orient PCP in the wing,53 results in cystic kidney disease.8 These studies underscore noncanonical Wnt PCP roles upstream or in conjunction with Dishevelled during kidney tubulogenesis.

In addition to roles in the formation and orientation of cilia and oriented cell division, vertebrate PCP signaling components have common roles in morphogenic directed cell migration, as occurs in gastrulation, convergent extension, and neurulation. Disruption of vertebrate PCP components results in common phenotypic outcomes including defects in gastrulation and neural tube closure and morphogenic processes involving cell migration dependent upon Rho family small-GTPase activity.54–61 PCP-mediated Rho activation involves the formin protein Daam1 (Dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis), which together with its associated Rho-GEF, WGEF, participates in cytoskeletal regulation (e.g., convergence and extension movements).61,62 Formin proteins modulate actin polymerization by coordinating the association of actin monomers, recruited by profilin proteins, to the barbed, elongating ends of filamentous actin.63–65 Because most other PCP effectors, including JNK and small GTPases, act in additional non-PCP pathways, Daam1 appears to provide a useful entry point to more selectively evaluate PCP signaling. Upon binding Dishevelled, Daam1's autoinhibition is relieved, allowing it to promote Rho activation and actin polymerization.66 Additionally, the actin-monomer binding proteins profilin-1 and profilin-2 are direct effectors of Daam1, with each exhibiting distinct roles in gastrulation.67–69 Thus, Daam1 provides a molecular target linking PCP signaling and cytoskeletal events. Daam1 and WGEF each provide an important and accessible experimental opportunity to assess the Daam1/WGEF/Rho trajectory's role in tubule morphogenesis.

Although there is growing evidence linking kidney development and disease with noncanonical Wnt PCP signaling, the role of PCP components directly regulating the actin cytoskeleton in tubulogenesis has not been established. In this study, we show that Daam1 and WGEF are expressed in the developing pronephros, and we use amphibian (Xenopus laevis) and fish (Danio rerio) model systems to show that Daam1, WGEF, and Rho are required for generating proper tubule morphologies.

RESULTS

Daam1 and WGEF Are Expressed in the Developing Xenopus Pronephros

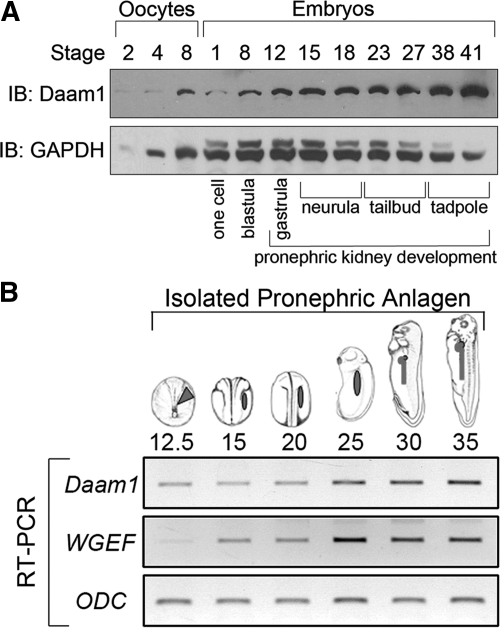

To assess whether the temporal protein levels of Daam1 are consistent with its possible involvement in pronephric development, we conducted immunoblot analysis using a characterized antibody directed against Daam1.68 Daam1 protein is present in whole Xenopus egg and embryo lysates, maternally through tadpole stages, overlapping with pronephric kidney formation from gastrulation (stage 12.5) through tadpole stages (stage 41) (Figure 1A). To examine Daam1 and WGEF spatial expression across embryonic kidney development, reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was undertaken of surgically isolated pronephric regions from Xenopus, demonstrating expression of both transcripts between stages 12.5 and 35. Transcript levels intensified at roughly stage 25, before differentiation and morphogenesis of the pronephric epithelium (Figure 1B). In situ hybridization studies in whole animals showed that Daam1 and WGEF transcripts are expressed over a range of embryonic stages (Supplementary Figure S1). When compared with sense control probes, Daam1 and WGEF antisense probes detected Daam1 and WGEF transcripts within the pronephric tubule and duct at stage 41 (data not shown), a stage not assessed in prior in situ studies.62,70 Thus, Daam1 and WGEF transcripts were detected earlier via RT-PCR (Figure 1B) than using in situ methods (data not shown).62,70 Collectively, the temporal and spatial expression profiles of Daam1 and WGEF are compatible with potential contributions toward kidney development.

Figure 1.

Daam1 protein is detectable during Xenopus pronephric development, with Daam1 and WGEF transcripts expressed in the developing pronephros. (A) Immunoblot (IB) of lysates from stage 2 to 8 oocytes and stage 1 to 41 embryos (approximately 1/2 oocyte or embryo per lane), showing Daam1 and GAPDH (loading control) protein from oocyte through tailbud stages, a timeline encompassing pronephric development (stages 12.5 to 41). (B) RT-PCR of pronephric anlagen isolated from stage 12.5 to 35 embryos showing expression of Daam1 and WGEF, with intensification at stage 25 during pronephric differentiation and morphogenesis.

Daam1 Depletion in Xenopus Alters the Expression of Late but Not Early Pronephric Markers

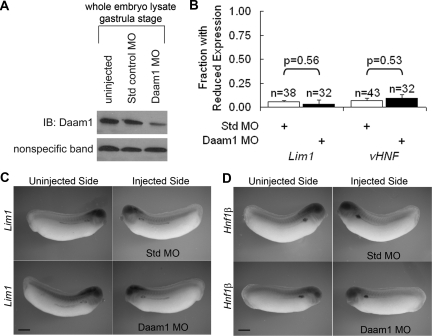

As a first test of Daam1's involvement in pronephric development, we examined effects upon nephric marker expression after its depletion. Knockdown of Daam1 was achieved using an established translation blocking Daam1 morpholino (MO) targeting the transcript's 5′ untranslated region.61 Immunoblot analysis confirmed the reduction of Daam1 protein levels in gastrula-stage embryos as compared with uninjected or standard control (Std MO)-injected embryos (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Daam1 knockdown in Xenopus does not affect expression of early pronephric determination and patterning markers. (A) Single-cell embryos were uninjected, injected with 40 ng of Std MO, or injected with 40 ng Daam1 MO. IB analysis from gastrula-stage embryos (approximately 1 embryo equivalent per lane) shows Daam1 protein levels were reduced in Daam1-MO-injected embryos as compared with uninjected or Std-MO-injected embryos. (B through D) The left V2 blastomere of eight-cell stage embryos was injected with 20 ng of Std MO or Daam1 MO. Embryos developed until stage 29 to 30 and were analyzed for Lim1 or Hnf1β expression levels on their injected (left) versus uninjected (right) sides. (B) The fraction of Daam1-depleted embryos with reduced Lim1 and Hnf1β marker expression on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side was similar to that of Std-MO-injected controls. (C) Injected sides of Daam1-MO and Std-MO-injected embryos do not have reduced Lim1 expression. (D) Injected sides of Daam1-MO- and Std-MO-injected animals do not have reduced Hnf1β expression. (C, D) Bars are 500 μm.

Because Daam1 and WGEF are expressed in the developing pronephros (Figure 1), we assessed knockdown effects on early pronephric markers of patterning and determination, Lim1 and vHNF. By injecting MO into the V2 blastomere on the left side of eight-cell stage Xenopus embryos, in combination with a nuclear-mCherry membrane green fluorescent protein (GFP) lineage tracer,71 spatial targeting of the pronephric anlagen was achieved and confirmed. Embryos were allowed to develop until stage 28 to 30 and then analyzed for Lim1 or Hnf1β expression by in situ hybridization (Figure 2B through 2D). The small fraction of animals with reduced expression of Lim1 or Hnf1β markers on the Daam1-MO injected as compared with the uninjected side of the embryo was similar to that seen with Std-MO-injected negative controls (Figure 2B through 2D). Our in situ hybridization data therefore suggest that targeted Daam1 depletion does not disrupt early development of the pronephros.

Because Daam1 and WGEF expression was found to intensify at stage 25 after the pronephros is patterned and determined (Figure 1B), pronephric Daam1 depletion may affect differentiation and/or morphogenesis. We therefore assessed the effect of Daam1 knockdown on epithelial markers within the glomus (similar to the metanephric glomerulus), proximal tubules, distal tubules, and collecting ducts using a similar V2 blastomere targeting strategy as noted above (Figure 3A). Embryos were allowed to develop until stage 38 to 40 and were then analyzed via in situ hybridization for the expression of Nephrin (nphs1; glomus), Chloride Channel (clckb; distal tubule and duct), Sodium Glucose Cotransporter (slc5a1; proximal tubules), and Sodium Potassium ATPase (atp1a1; tubules and duct). After Daam1 knockdown, the fraction of animals with reduced expression of nphs1 on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side of the embryo was similar to that of the Std-MO-injected controls (Figure 3B). In contrast, the fraction of animals with reduced expression of clckb, slc5a1, or atp1a1 in Daam1-MO-injected as compared with uninjected embryo sides was greater than that for Std-MO-injected controls (Figure 3B). Although there was no observable loss in nphs1 expression (Figure 3, B and C), Daam1-MO-injected animals exhibited significant reductions in expression of clckb within the distal tubules and ducts, slc5a1 within the proximal tubules, and atp1a1 in tubules and ducts (Figure 3, B and D through F). The reductions in expression of these markers appears to result primarily from reduced tubule elaboration rather than reduced intensity of expression, suggesting that the epithelium has properly differentiated but that morphogenesis is disrupted. In all cases, these data together suggest that Daam1's function is crucial during subsequent differentiation and morphogenesis stages to form the proximal and distal tubules and collecting ducts of the pronephros.

Figure 3.

Daam1 knockdown reduces the expression of late pronephric markers of differentiation and morphogenesis in Xenopus. (A) Diagram of Xenopus pronephric kidney showing positions of proximal tubules, distal tubules, collecting duct, and glomus. (B through F) The left V2 blastomere of eight-cell stage embryos was injected with 20 ng of Std MO or Daam1 MO. Embryos developed until stage 38 to 40 and were analyzed for nphs1, clckb, slc5a1, and atp1a1 expression levels on their injected (left) side as compared with their uninjected (right) side. (B) The fraction with reduced nphs1 marker expression on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for Daam1-MO-injected animals was similar to that of Std-MO-injected controls, whereas the fraction with reduced clckb, slc5a1, and atp1a1 expression on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for Daam1-MO-injected animals is greater than that for Std-MO-injected controls. (C) Injected sides of Std-MO- and Daam1-MO-injected animals do not have reduced nphs1 expression. (D) Injected sides of Std-MO-injected animals do not have reduced clckb expression, whereas injected sides of Daam1-MO-injected animals have significantly reduced clckb expression. (E) Injected sides of Std-MO-injected animals do not have reduced slc5a1 expression, whereas injected sides of Daam1-MO-injected animals have significantly reduced slc5a1 expression. (F) Injected sides of Std-MO-injected animals do not have reduced atp1a1 expression, whereas injected sides of Daam1-MO-injected animals have significantly reduced atp1a1 expression. (C through F) Bars are 500 nm.

Daam1 Depletion Alters Morphogenesis of the Pronephric Tubules and Duct in Xenopus

Because Daam1 depletion reduces marker expression of the mature pronephric epithelium and appears to alter pronephric morphology, we conducted a more thorough analysis of shape changes of the tubules and duct. Proximal tubule architecture was evaluated using the 3G8 antibody (unknown epitope) or lectin (sugar binding protein) staining, whereas that of distal tubules and duct used the 4A6 antibody (P.D. Vize, personal communication) (Figure 4A).72

Figure 4.

Daam1 knockdown alters morphogenesis of the pronephric tubules and duct and can be rescued by flDaam1 as assessed by markers of the mature pronephros in Xenopus. (A) Diagram of Xenopus pronephric kidney showing positions of lectin staining in the proximal tubules (green) and 4A6 antibody staining in the distal tubules and collecting duct (red). (B through F) The left V2 blastomere of eight-cell stage embryos was injected with 20 ng of Std MO or Daam1 MO. Embryos developed until stage 38 to 40 and were analyzed for lectin, 4A6 antibody, and 12/101 antibody staining within the proximal tubules, distal tubules/duct, and somites, respectively, on their injected (left) side as compared with their uninjected (right) side. (B) The PNI is greater in Daam1-MO-injected animals than in Std-MO-injected animals. (C) The fraction with reduced proximal tubule and distal tubule/duct marker staining on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for Daam1-MO-injected animals is greater than that for Std-MO-injected controls, whereas the fraction with reduced somite marker staining on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for Daam1-MO-injected animals was similar to that of Std-MO-injected controls. (D) Injected sides of Std-MO-injected animals do not have reduced proximal tubule marker staining, whereas injected sides of Daam1-MO-injected animals have significantly reduced proximal tubule marker staining. Bar is 100 μm. (E) Injected sides of Std-MO-injected animals do not have reduced distal tubule and duct marker staining, whereas injected sides of Daam1-MO-injected animals have significantly reduced distal tubule and duct marker staining. Bar is 100 μm. (F) Injected sides of Std-MO- or Daam1-MO-injected animals do not have reduced somite marker staining. Bar is 250 μm. (G through M) The left V2 blastomere of eight-cell stage embryos was injected with 20 ng Std MO + 1 ng β-gal, 20 ng Daam1 MO + 1 ng β-gal, or 20 ng Daam1 MO + 1 ng flDaam1. Embryos developed until stage 38 to 40 and were analyzed for lectin, 4A6 antibody, and 12/101 antibody staining within the proximal tubules, distal tubules/duct, and somites, respectively, on their injected (left) side as compared with their uninjected (right) side. (G) The PNI is greater in Daam1-MO + β-gal-injected animals than in Std-MO + β-gal embryos or Daam1-MO + flDaam1-injected rescue animals. (H) The fraction with reduced proximal tubule marker staining on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for Daam1 MO + β-gal-injected animals was greater than that of Std-MO + β-gal-injected controls. This reduction in proximal tubule staining seen in Daam1 MO + β-gal animals was rescued in Daam1-MO + flDaam1-injected animals. (I) The fraction with reduced distal tubule and duct marker staining on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for Daam1-MO + β-gal-injected animals was greater than that of the Std-MO + β-gal-injected controls. This reduction in distal tubule and duct staining seen in Daam1 MO + β-gal animals was rescued in Daam1 MO + flDaam1-injected animals. (J) The fraction with reduced somite marker staining on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for was similar for Std-MO + β-gal-, Daam1-MO + β-gal-, and Daam1-MO + flDaam1-injected animals. (K) Injected sides of Std-MO + β-gal-injected animals do not have reduced proximal tubule marker staining, whereas injected sides of Daam1-MO + β-gal injected animals have significantly reduced proximal tubule marker staining. This loss of proximal tubule marker staining is rescued in Daam1-MO + flDaam1-injected animals. Bar is 100 μm. (L) Injected sides of Std-MO + β-gal-injected animals do not have reduced distal tubule and duct marker staining, whereas injected sides of Daam1-MO + β-gal-injected animals have significantly reduced distal tubule and duct marker staining. This loss of staining with the distal tubule and duct marker is rescued in Daam1-MO + flDaam1-injected animals. Bar is 100 μm. (M) Injected sides of Std-MO + β-gal-, Daam1-MO + β-gal-, and the Daam1-MO + flDaam1-injected animals do not have reduced somite marker staining. Bar is 250 μm.

To quantitatively assess the effects of perturbing Daam1 pathway components on proximal tubule morphogenesis, an established pronephric index (PNI) scoring system was utilized that compares the development of proximal tubule components on the injected (left) sides versus uninjected (right) sides.73 The PNI system assigns one point for each of the five proximal tubule components of the mature pronephros (stage 38 visualized using the proximal tubule marker 3G8 antibody or lectin); this results in fully developed proximal tubules receiving a score of 5. Unformed tubules receive a score of 0, and scores for partially formed tubules range between 1 and 4. The PNI is expressed as the number of tubule components on the uninjected (right) sides minus that on the injected (left) sides of the embryo. Thus, experimental conditions that significantly reduce tubule components result in high PNI values, whereas conditions of little consequence result in low PNI values.73 Originally, the PNI system was stringently defined such that values ≥2 were considered significant.73 However, within our studies, PNI values <2 were shown to be significant in certain experimental cases on the basis of repeated observations and statistical analyses, thereby supporting the existence of subtle changes in pronephric development at later stages of epithelialization and morphogenesis.

Relative to Std-MO-injected controls, Daam1 pronephric depletion reduced tubule elaboration and branching in pronephic proximal segments (Figure 4, B through D). This was reflected in PNI values being significantly greater after pronephric Daam1 knockdown (Figure 4B). Similar results were obtained using a dominant negative N-Daam1 construct (data not shown).61 Tubule and duct morphogenesis was further assessed, with Daam1 depletion leading to reduced proximal and distal tubules and ducts. To assess a possible secondary effect contributing to the observed alterations, we examined somite integrity because earlier work implicated somite involvement in pronephrogenesis.74 After examination of Daam1-MO- versus Std-MO-injected animals (12/101 antibody/myofiber marker), no significant loss in somite integrity was observed (Figure 4, C and F).

To assess the specificity of Daam1 MO effects, we wished to test if the above noted pronephric morphogenic defects could be rescued using co-injected full-length Daam1 (flDaam1; resistant to Daam1 MO).61 First, we assessed if flDaam1 overexpression itself within the developing pronephros produced a phenotype. However, unlike other PCP components producing overexpression phenotypes,54,55 Daam1 is autoinhibited (when not bound to Dishevelled),61 likely accounting for relatively subtle phenotypic effects upon its overexpression (Supplemental Figure S2). The rescuing capacity of flDaam1 expression upon Daam1 MO depletion was then evaluated. β-Galactosidase (β-gal) was used as a negative control for rescue. As expected, Daam1 MO depletion in the presence of β-gal continued to result in fewer proximal tubule components (no rescue) relative to Std MO + β-gal-injected controls (Figure 4G). In contrast, flDaam1 exhibited clear rescuing capacity (Figure 4G). Similarly, as evaluated using a prior noted antibody or lectin staining, we determined that flDaam1 significantly rescued proximal tubules (Figure 4, H and K) as well as distal tubules and ducts (Figure 4, I and L). The fraction of animals with reduced somite staining suggested a negligible likelihood of secondary effects upon the pronephros (Figure 4, J and M). These data together demonstrate that our MO-directed pronephric depletion of Daam1 is specific.

Daam1 Depletion Has Little Effect on Proliferation or Apoptosis within Pronephric Tubules

In addition to effects upon differentiation or morphogenesis, reduced staining of pronephric markers might result from the loss of cells through decreased proliferation, increased apoptosis, or from changes in cell size. As assessed by in situ staining using the atp1a1 marker, we first observed that Daam1 depletion results in reduced cell number rather than cell size (data not shown). We then tested whether Daam1 depletion altered proliferation or apoptosis at two time points after the increase of endogenous Daam1 and WGEF expression at stage 25. Cell proliferation, assessed using a phospho-histone H3 antibody,75,76 was not effected by Daam1 depletion within the pronephric region at stage 27 (data not shown). An apparently small decrease in proliferation was observed in stage 32 pronephric proximal tubules after Daam1 depletion (an averaged difference of <1 cell per kidney) (Supplemental Figure S3). Because tubule staining (3G8 antibody), and likely the total cell number within Daam1-depleted pronephroi, is reduced compared with controls, this small difference is even less likely to be meaningful. As measured using an active caspase-3 antibody77 after Daam1 depletion, no measurable apoptosis within the pronephros was detected at stage 27 (data not shown) or stage 32 (Supplemental Figure S4). As a positive control, apoptosis was readily detectable in somite regions at both stages, and exposure of embryos to doxorubicin, an inhibitor of DNA replication, produced apoptosis in 100% of pronephroi and most other tissues. These data suggest that depletion of Daam1 has negligible effects on proliferation and apoptosis and that the observed alterations in pronephric tubular structure are likely due to effects upon differentiation and morphogenesis.

WGEF Depletion in Xenopus Perturbs Pronephric Tubule and Duct Morphogenesis

To further test the role of the Daam1 trajectory of the PCP pathway in pronephric tubulogenesis, WGEF, a Rho-GEF that associates with Daam1, was depleted within the pronephric field. Staining with proximal and distal tubule markers (Figure 5A) was assessed following established MO-based WGEF knockdown using a strategy similar to that used with Daam1 knockdown.62 The PNI scoring for reduced tubule components was significantly greater in WGEF-depleted than Std-MO-injected animals (Figure 5B). Likewise, the fraction of injected animals with reduced marker staining of the proximal tubule or distal tubules and duct was greater for WGEF-MO- than Std-MO-injected controls (Figure 5, C through E). Indeed, the pronephric phenotype resulting from WGEF knockdown was more severe than that after Daam1 knockdown (Figure 4, B and C, and Figure 5, B and C). Somite integrity was similar in WGEF-MO- versus Std-MO-injected embryos (Figure 5, C and F). Possibly because Daam1 and WGEF physically interact,62 their co-depletion caused similar reductions in staining of pronephric proximal tubules, distal tubules, and ducts, as seen for single depletions (Supplemental Figure S5). These findings support a role of the Daam1/WGEF trajectory of the PCP pathway in pronephric tubulogenesis.

Figure 5.

WGEF knockdown and DN Rho alter morphogenesis of the pronephric tubules and duct as assessed by markers of the mature pronephros in Xenopus. (A) Diagram of Xenopus pronephric kidney showing positions of lectin staining in the proximal tubules (green) and 4A6 antibody staining in the distal tubules and collecting duct (red). (B through F) The left V2 blastomere of eight-cell stage embryos was injected with 20 ng of Std MO or WGEF MO. Embryos developed until stage 38 to 40 and were analyzed for lectin, 4A6 antibody, and 12/101 antibody staining within the proximal tubules, distal tubules/duct, and somites, respectively, on their injected (left) side as compared with their uninjected (right) side. (B) The PNI is greater in WGEF-MO-injected animals than in Std-MO-injected animals. (C) The fraction with reduced proximal tubule and distal tubule/duct marker staining on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for WGEF-MO-injected animals is greater than that for Std-MO-injected controls, whereas the fraction with reduced somite marker staining on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for WGEF-MO-injected animals was similar to that of Std-MO-injected controls. (D) Injected sides of Std-MO-injected animals do not have reduced proximal tubule marker staining, whereas injected sides of WGEF-MO-injected animals have significantly reduced proximal tubule marker staining. Bar is 100 μm. (E) Injected sides of Std-MO-injected animals do not have reduced distal tubule and duct marker staining, whereas injected sides of WGEF-MO-injected animals have significantly reduced distal tubule and duct marker staining. Bar is 100 μm. (F) Injected sides of Std-MO- or WGEF-MO-injected animals do not have reduced somite marker staining. Bar is 250 μm. (G through K) The left V2 blastomere of eight-cell stage embryos was injected with 200 pg of β-gal or DN Rho. Embryos developed until stage 38 to 40 and were analyzed for lectin and 4A6 antibody staining within the proximal tubules and distal tubules/duct, respectively, on their injected (left) side as compared with their uninjected (right) side. (G) The PNI is greater in the DN-Rho-injected animals than the β-gal-injected animals. (H) The fraction with reduced proximal tubule and distal tubule/duct marker staining on the injected side as compared with the uninjected side for DN-Rho-injected animals is greater than that for β-gal-injected controls. (I) Injected sides of β-gal-injected animals do not have reduced proximal tubule marker staining, whereas injected sides of DN-Rho-injected animals have significantly reduced proximal tubule marker staining. (J) Injected sides of β-gal-injected animals do not have reduced distal tubule and duct marker staining, whereas injected sides of DN-Rho-injected animals have significantly reduced distal tubule and duct marker staining. (I, J) Bars are 100 μm. (K) Injected sides of DN-Rho-injected animals do not have reduced somite marker staining. Bar is 250 μm.

Dominant Negative Rho Alters Pronephric Tubule and Duct Morphogenesis in Xenopus

Because the Daam1/WGEF PCP trajectory leads to the activation of Rho GTPase, we examined whether Rho is indeed required for pronephros formation. Dominant negative RhoN19 (DN Rho) was injected into the V2 blastomere of eight-cell stage embryos, followed by staining for markers of proximal tubules or of distal tubules and ducts (Figure 5A).78–80 DN Rho injection resulted in PNI values significantly greater than for β-gal-expressing animals, meaning that the number of proximal tubule components was reduced (Figure 5G). Markers of proximal tubules, distal tubules and ducts, and somites further indicated that DN Rho has an inhibitory effect upon tubule, duct, and somite formation (Figure 5, H through K).

Daam1 Depletion in Zebrafish Reduces Kidney Tubulogenesis and Alters Morphogenesis

To support that the role of the Daam1 trajectory in nephrogenesis is not restricted to Xenopus, we examined Daam1 depletion in zebrafish (D. rerio) using an established MO.81 The mature zebrafish pronephric kidney has an architecture similar to the Xenopus pronephros, containing a glomus, nephrostomes, tubules, and ducts (Supplemental Figure S6A). Zebrafish pronephroi exhibit a characteristic shape, including nephrostomes that turn in toward the midline and pronephric tubules and ducts that run parallel to each other but never touch or branch (Supplemental Figure S6A). We injected single-cell zebrafish embryos with Daam1 MO versus Std MO, allowing then to develop 72 hours postfertilization. Pronephric tubule and duct shapes were assessed using the α6F antibody, which recognizes the α subunit of the sodium potassium ATPase. Whereas Std-MO-injected animals shared the characteristic pronephric shapes of uninjected embryos, Daam1-MO-injected animals exhibited the absence of nephrostomes or those that did not turn inward toward the midline (Supplemental Figure S6C). Furthermore, evidencing phenotypes rarely seen under normal conditions, tubules and ducts became wavy (convoluted) after Daam1 depletion (Supplemental Figure S6, B and D), occasionally branching and frequently touching (Supplemental Figure S6E). Because MOs are usually injected at the single-cell stage in zebrafish, multiple morphogenic tissues or events may have been influenced, including convergence-extension of the elongating embryo. Thus, analysis of convergent-extension was performed after Daam1 depletion; as anticipated, nearly all such embryos exhibited convergent-extension defects in contrast to Std-MO-injected animals (Supplemental Figure S6F). In summary, disruption of the Daam1 PCP trajectory in zebrafish results in morphogenic defects of the pronephros, possibly reflecting Daam1's conserved role across vertebrate species.

DISCUSSION

Tubulogenesis is integral to the formation and function of multiple organ systems, including the kidney, lung, mammary and prostate glands, digestive tract, and cardiovascular and auditory systems. In each case, Wnt signals are crucial for the induction and morphogenesis of these tubular assemblies.17–29 Although Wnt signaling requirements in kidney formation are accepted, 2,41–48,82 understanding the relative contributions of varying Wnt components and trajectories remains a key question. For example, β-catenin-mediated (canonical Wnt) signaling is essential in inducing kidney tubulogenesis,1,2,83–85 whereas studies have only begun to examine noncanonical Wnt PCP contributions. Several PCP components or regulators that establish the plane of polarization within cells are recognized players, such as Wnt9b, Fat4, Vangl2 (homolog of Van Gogh), Inversin (homolog of Diego), and Seahorse.8–10,14,15 However, involvement of PCP effectors that regulate actin dynamics have not yet been studied in kidney formation or in tubulogenesis. Our study demonstrates that Daam1 and WGEF, components of the vertebrate PCP pathway involved in cytoskeletal modulation, are expressed in the developing kidney and are required for pronephric tubule morphogenesis in Xenopus and likely also in zebrafish (Figures 1, 4, and 5 and Supplemental Figure S6).

Several studies support the hypothesis that Wnt signaling initially acts via canonical Wnt/β-catenin signals that become attenuated and supplanted by noncanonical Wnt pathways. Supportive primary evidence for this idea includes studies in which β-catenin overexpression prevents kidney tubules from forming.1,2 Additionally, within ex vivo mouse kidney explants derived from Wnt4 or Wnt9b knockout mice, exogenous β-catenin rescues condensation of the metanephric mesenchyme but fails to rescue subsequent tubule formation.1 This is consistent with the idea that signals in addition to β-catenin and downstream of Wnts are needed in nephrogenesis. Studies in zebrafish suggest that the PCP component Inversin (homolog of Diego) attenuates canonical Wnt signaling and simultaneously induces PCP signaling through selective degradation of cytoplasmic Dishevelled.15 However, the nature of the noncanonical components that attenuate canonical signaling remain poorly resolved. The studies presented here indicate that the Daam1/WGEF trajectory of the PCP pathway is required for the elaboration and morphogenesis phases of nephric tubulogenesis rather than for mesenchyme induction (Figures 2 and 3); that is, after β-catenin induction/condensation of the nephrogenic mesenchyme, we propose that the Daam1/WGEF trajectory contributes to the epithelialization and morphogenesis of developing nephrons. Because the pronephric WGEF knockdown phenotype is more severe than those after knockdown of Daam1 or inhibition of Rho activity, WGEF may play additional roles (beyond the Daam1 trajectory) within these developmental processes.

To this point, disruption of PCP components in the developing kidney, including Wnt9b, Fat4, Vangl2 (homolog of Van Gogh), Inversin (homolog of Diego), and Seahorse, leads to morphologic defects reminiscent of cystic kidney disease in humans.8–10,14,15 These components establish the plane of polarity to coordinate asymmetric signaling by downstream PCP effectors such as Daam1, leading to alteration of the actin cytoskeleton.86,87 Unexpectedly, Daam1 knockdown does not show an obvious cystic kidney phenotype in Xenopus (Figure 4), although in zebrafish a small fraction of animals exhibited cystic kidneys.81 Differences in kidney phenotypes after perturbation of distinct PCP components may in part be a consequence of their relative positions within the PCP pathway. For example, components modulating a greater number of key effectors might be expected to have a more substantial effect on morphogenic processes than Daam1. Alternatively, Daam1 may play a role in cystic kidney disease but in combination with other unresolved factors. Hypomorphic Wnt9b expression in collecting duct stalks of mouse kidney results in a cystic defect thought to be primarily caused by failure of tubules to elongate in the face of misoriented cell divisions.9 These hypomorphs also display reduced Rho and JNK activation, although it is unknown if this is instrumental in forming nephric cysts.9 Thus, although Rho disruption upon Daam1 knockdown does not notably produce nephric cysts on its own, it may do so in combination with other (PCP, etc.) disruptions.

Studies to substantiate the role of PCP signaling in kidney tubulogenesis and cystic kidney disease are accumulating,9,10,14,15,51 but the mechanisms underlying PCP involvement in shaping kidney tubules have remained largely unclear. For example, work has examined PCP participation in establishing the plane of polarity within tissues in relation to cilia formation and orientation as well as oriented cell divisions.10,14,15,51 However, the relevance of PCP signaling to cytoskeletal modulation, leading to directional cell movements in morphogenic processes such as gastrulation, convergent extension, and neurulation, suggests that PCP may also be involved in nephric tubulogenesis.88–93 Daam1 and WGEF are central players in PCP effects upon cytoskeletal architecture, which occur through the modulation of formin and Rho GTPase activities. Our work, in combination with previous studies of Daam1 in other tissues/systems,61,62,66,68,69 appears consistent with its role in PCP-directed cytoskeletal rearrangements in nephric morphogenesis.

Our understanding of the role of Wnt signaling in tubulogenesis is growing because of the application of multiple animal models and differing organ systems. Commonalities exist between tubulogenic systems including kidney, lung, heart, and stomach, such as the requirement of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling at early stages followed by its attenuation during further development.1–7 Noncanonical Wnt signals are necessary in direct tubule branching of kidney, lung, and mammary gland, likely via contributions to directional cell migration.8–15 PCP is also linked with orientating the primary cilia of several tissues, including the kidney and inner ear, and ciliary signaling in turn has an effect on noncanonical signaling in the developing kidney.8,10,14,15,94–101 Although our evidence supports the role of PCP signaling in nephric tubulogenesis, the involvement of more downstream signaling components will require future work. The role of PCP signaling in processes such as gastrulation, convergent extension, and neurulation, and specifically in tissues including the kidney, will ultimately help to resolve its mechanistic involvement in tissue movements and cell-shape changes contributing to tube generation. In all cases, our findings show that there is a conserved requirement for the Daam1 trajectory of the PCP signaling pathway in the morphogenesis of tubular structures.

CONCISE METHODS

Embryos

X. laevis embryos were obtained, reared,102 and visualized (Nikon model SMZ-U and Zeiss Stemi DV4). Zebrafish embryos, D. rerio strain DZ, were reared103 and staged.104

Western Blots

Oocytes were isolated from adult female X. laevis.105 Embryos were collected at various stages.106 Protein lysates were made107 and boiled for 5 minutes at 95°C in 2× Laemmeli (BioRad) with 100 μΜ dithiothreitol. Ten to 20 μl of lysate (0.5 to 1 oocyte or embryo equivalent) were run on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel and transblotted to nitrocellulose. Blots were exposed to a rabbit Daam1 antibody (1:1000)68 and/or a rabbit glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody (1:5000) (Santa Cruz FL-335) followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase secondary (BioRad) and enhanced chemiluminscence (Pierce Supersignal West Pico).

RT-PCR Analysis

The pronephric anlagen was dissected from X. laevis embryos ranging from stages 12.5 to 35 and homogenized in 150 μl XT buffer (300 mM sodium chloride, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS). Total RNA was isolated from pronephric anlagen and was used to generate first-strand cDNA.108 The relative quantity of input cDNA was assessed by comparing ODC (ornithine decarboxylase) PCR band intensities. Linearity of PCR amplification was confirmed with consecutive doubling dilutions of input cDNA.47 Primers used are as follows: Daam1-forward 5′-AGTCGATGGAGCCAGCATTG-3′, Daam1-reverse 5′-GCTTGGTCCTAAGTGCAGTC-3′, WGEF-forward 5′-CTCCATAGCCGTCGATCATT-3′, WGEF-reverse 5′-TGTTCCTGATACGCCTGGTT-3′, ODC-forward 5′-GGAGCTGCAAGTTGGAGA-3′, and ODC-reverse 5′-TCAGTTGCCAGTGTGGTC-3′.

In Situ Hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes were prepared using the DIG RNA labeling kit (Roche). The constructs were linearized and synthesized using the listed enzyme and polymerase: CDaam1-antisense EcoRI/T7-sense NotI/Sp6,61 NDaam1-antisense StuI/T7-sense NotI/Sp6,61 WGEF-antisense HindIII/T7-sense NotI/Sp6,62 Lim1-antisense XhoI/T7,109,110 HNF-antisense SmaI/T7,111 Nephrin-antisense SmaI/T7,112 ClcK-antisense EcoRI/T7,113 NaGluc-antisense SmaI/T7,114 and NaKATPase-antisense SmaI/T7b.115 Embryos were collected, fixed, and processed as described, eliminating the triethanolamine and acetic anhydride steps.116

Molecular Cloning

A nuclear-mCherry membrane-GFP construct containing H2b-mCherry and glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor-GFP71 was cloned into the pCS2 vector using the XhoI and XbaI restriction sites.

MOs and RNA Constructs

Published X. laevis translation-blocking MOs targeting the 5′ untranslated region of Daam1 5′-CCGCAGGTCTGTCAGTTGCTTCTA-3′ and WGEF 5′-TCATTGTGTGAGTCCATCAGTCCCG-3′ were used with Std MO 5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′.61,62 For zebrafish Daam1 knockdowns, a splice-blocking MO targeting 5′-TCTTGACTTGCCCACCTGAAAGCGC-3′ at the exon 6/intron 6 junction was used with the above listed Std MO.81 cDNA constructs included flDaam1 and dominant negative NDaam1,61 DN Rho,78–80 and a bicistronic nuclear-mCherry membrane-GFP.71 cDNA constructs were linearized using NotI, transcribed in vitro using the SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion), and purified.107

Microinjections and Drug Treatment

X. laevis microinjections were performed as described previously.107 For targeting of constructs and MOs to the pronephros, microinjections were made into the V2 blastomere at the eight-cell stage,106 which contributes primarily to the pronephros, dorsal and ventral fin epidermis, trunk crest, dorsal spinal chord, dorsal and ventral somite, lateral plate fin mesenchyme, central somite, hindgut, and proctodeum.117,118 Targeting of injected constructs was verified by co-injection with nuclear-mCherry membrane-GFP.71 Zebrafish microinjections were performed at the single-cell stage.119 Uninjected X. laevis embryos at stages 27 and 32 were treated with a 1:1000 dilution of doxorubicin hydrochloride (EMD Chemicals, KS13305, 5 μg/μl) in 0.1× Marc's modified ringers solution for 4 hours before fixation.

Immunostaining

X. laevis and zebrafish embryos were stained as described previously.2 Proximal tubules were detected using fluorescein-coupled Erythrina cristagalli lectin at 50 μg/ml (Vector Labs) (PD Vize, personal communication) or primary monoclonal antibody 3G8 (1:30; unknown epitope),72 whereas distal tubules and ducts and somites were detected using monoclonal 4A6 (1:5) antibody (unknown epitope)72 and monoclonal 12/101 (myofiber marker; 1:100), respectively.120,121 Cell proliferation and apoptosis were respectively assayed using Upstate anti-phospho-Histone H3 (06-570) and BD PharMingen rabbit anti-active Caspase-3 (551150) antibodies.75–77 Staining was visualized using goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:2000) coupled to alkaline phosphatase (AP) (Zymed) or goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa 488 or Alexa-555 (Invitrogen). In zebrafish, monoclonal antibody α6F (α-1 subunit of NaK ATPase) with goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:2000) AP (Zymed) and nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate AP substrate (Roche) were used to detect tubules and ducts.122,123 Embryos stained with AP reagents were bleached as described previously.124 Zebrafish embryos were dehydrated in methanol and cleared in Murray's clearing medium.102

Imaging

Images were captured with an Olympus SZX12 stereomicroscope with a DF PLFL 1.6× PF objective and an Olympus DP71 12.5 megapixel camera and software (version 3.3.1.292). Images were assembled using Adobe CS4 Photoshop and Illustrator.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful Jun-Ichi Kyuno for his experimental contributions to the manuscript. Unfortunately, we are unable to include him as third author because of journal copyright restraints. We thank all members of the Houston Frog and Fish Club for helpful suggestions, in particular laboratory members of P.D. McCrea, A.K. Sater, J. Kuang, and D.S. Wagner. We also thank D. Gu and J.Y. Hong for training of R.K.M. in the methodology of Xenopus research. We are particularly grateful to I.B. Dawid, M. Kloc, P.D. Vize, R.R. Behringer, V. Huff, M.C. Barton, and F. Costantini for reagents and advice. Additionally, we thank Y. Furuta for the use of his stereomicroscope and J.L. Polan for microscopy training. We are grateful to Thomas Dunham and Jessica Tyler for assistance with analysis of staining within the cover image. This work was supported by an National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grant (GM052112), the March of Dimes (1-FY-07-461-01), an NIH training grant (HD07325 to R.K.M.), an NIH postdoctoral National Research Service Award (DK082145 to R.K.M.), and a postdoctoral fellowship provided by the Odyssey Program and the Theodore N. Law Endowment for Scientific Achievement at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (UTMDACC) (R.K.M.). The DNA sequencing and other core facilities at UTMDACC were supported by UTMDACC National Cancer Institute core grant CA-16672.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Making a Tubule the Noncanonical Way,” on pages 1575–1577.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Park JS, Valerius MT, McMahon AP: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates nephron induction during mouse kidney development. Development 134: 2533–2539, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lyons JP, Miller RK, Zhou X, Weidinger G, Deroo T, Denayer T, Park JI, Ji H, Hong JY, Li A, Moon RT, Jones EA, Vleminckx K, Vize PD, McCrea PD: Requirement of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in pronephric kidney development. Mech Dev 126: 142–159, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rajagopal J, Carroll TJ, Guseh JS, Bores SA, Blank LJ, Anderson WJ, Yu J, Zhou Q, McMahon AP, Melton DA: Wnt7b stimulates embryonic lung growth by coordinately increasing the replication of epithelium and mesenchyme. Development 135: 1625–1634, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shu W, Jiang YQ, Lu MM, Morrisey EE: Wnt7b regulates mesenchymal proliferation and vascular development in the lung. Development 129: 4831–4842, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Langhe SP, Sala FG, Del Moral PM, Fairbanks TJ, Yamada KM, Warburton D, Burns RC, Bellusci S: Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) reveals that fibronectin is a major target of Wnt signaling in branching morphogenesis of the mouse embryonic lung. Dev Biol 277: 316–331, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Okubo T, Hogan BL: Hyperactive Wnt signaling changes the developmental potential of embryonic lung endoderm. J Biol 3: 11, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schneider VA, Mercola M: Wnt antagonism initiates cardiogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Genes Dev 15: 304–315, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saburi S, Hester I, Fischer E, Pontoglio M, Eremina V, Gessler M, Quaggin SE, Harrison R, Mount R, McNeill H: Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat Genet 40: 1010–1015, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karner CM, Chirumamilla R, Aoki S, Igarashi P, Wallingford JB, Carroll TJ: Wnt9b signaling regulates planar cell polarity and kidney tubule morphogenesis. Nat Genet 41: 793–799, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borovina A, Superina S, Voskas D, Ciruna B: Vangl2 directs the posterior tilting and asymmetric localization of motile primary cilia. Nat Cell Biol 12: 407–412, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Imbert A, Eelkema R, Jordan S, Feiner H, Cowin P: Delta N89 beta-catenin induces precocious development, differentiation, and neoplasia in mammary gland. J Cell Biol 153: 555–568, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cervantes S, Yamaguchi TP, Hebrok M: Wnt5a is essential for intestinal elongation in mice. Dev Biol 326: 285–294, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li C, Xiao J, Hormi K, Borok Z, Minoo P: Wnt5a participates in distal lung morphogenesis. Dev Biol 248: 68–81, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kishimoto N, Cao Y, Park A, Sun Z: Cystic kidney gene seahorse regulates cilia-mediated processes and Wnt pathways. Dev Cell 14: 954–961, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simons M, Gloy J, Ganner A, Bullerkotte A, Bashkurov M, Kronig C, Schermer B, Benzing T, Cabello OA, Jenny A, Mlodzik M, Polok B, Driever W, Obara T, Walz G: Inversin, the gene product mutated in nephronophthisis type II, functions as a molecular switch between Wnt signaling pathways. Nat Genet 37: 537–543, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yates LL, Schnatwinkel C, Murdoch JN, Bogani D, Formstone CJ, Townsend S, Greenfield A, Niswander LA, Dean CH: The PCP genes Celsr1 and Vangl2 are required for normal lung branching morphogenesis. Hum Mol Genet 19: 2251–2267, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merkel C, Karner C, Carroll T: Molecular regulation of kidney development: Is the answer blowing in the Wnt? Pediatric Nephrology 22: 1825–1838, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cardoso WV, Lu J: Regulation of early lung morphogenesis: Questions, facts and controversies. Development 133: 1611–1624, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robinson GW, Hennighausen L, Johnson PF: Side-branching in the mammary gland: The progesterone-Wnt connection. Genes Dev 14: 889–894, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rubin DC: Intestinal morphogenesis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 23: 111–114, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verzi MP, Shivdasani RA: Wnt signaling in gut organogenesis. Organogenesis 4: 87–91, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brade T, Manner J, Kuhl M: The role of Wnt signalling in cardiac development and tissue remodelling in the mature heart. Cardiovasc Res 72: 198–209, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cohen ED, Tian Y, Morrisey EE: Wnt signaling: An essential regulator of cardiovascular differentiation, morphogenesis and progenitor self-renewal. Development 135: 789–798, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Riccomagno MM, Takada S, Epstein DJ: Wnt-dependent regulation of inner ear morphogenesis is balanced by the opposing and supporting roles of Shh. Genes Dev 19: 1612–1623, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ohyama T, Mohamed OA, Taketo MM, Dufort D, Groves AK: Wnt signals mediate a fate decision between otic placode and epidermis. Development 133: 865–875, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Freter S, Muta Y, Mak SS, Rinkwitz S, Ladher RK: Progressive restriction of otic fate: The role of FGF and Wnt in resolving inner ear potential. Development 135: 3415–3424, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jayasena CS, Ohyama T, Segil N, Groves AK: Notch signaling augments the canonical Wnt pathway to specify the size of the otic placode. Development 135: 2251–2261, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller RK, McCrea PD: Wnt to build a tube: Contributions of Wnt signaling to epithelial tubulogenesis. Dev Dyn 239: 77–93, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ueno N, Greene ND: Planar cell polarity genes and neural tube closure. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 69: 318–324, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Saxén L: Organogenesis of the Kidney, New York, Cambridge University Press, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davidson AJ: Mouse kidney development. In: Stembook [Internet], edited by Melton D, Girard L. Cambridge, MA, Harvard Stem Cell Institute, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bouchard M, Souabni A, Mandler M, Neubuser A, Busslinger M: Nephric lineage specification by Pax2 and Pax8. Genes Dev 16: 2958–2970, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dressler GR: The cellular basis of kidney development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22: 509–529, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vize PD, Seufert DW, Carroll TJ, Wallingford JB: Model systems for the study of kidney development: Use of the pronephros in the analysis of organ induction and patterning. Dev Biol 188: 189–204, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jones EA: Xenopus: A prince among models for pronephric kidney development. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 313–321, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chan T, Asashima M: Growing kidney in the frog. Nephron Exp Nephrol 103: e81–e85, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brandli AW: Towards a molecular anatomy of the Xenopus pronephric kidney. Int J Dev Biol 43: 381–395, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wingert RA, Davidson AJ: The zebrafish pronephros: A model to study nephron segmentation. Kidney Int 73: 1120–1127, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Costantini F: Renal branching morphogenesis: Concepts, questions, and recent advances. Differentiation 74: 402–421, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schmidt-Ott KM, Barasch J: WNT/beta-catenin signaling in nephron progenitors and their epithelial progeny. Kidney Int 74: 1004–1008, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stark K, Vainio S, Vassileva G, McMahon AP: Epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney regulated by Wnt-4. Nature 372: 679–683, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kispert A, Vainio S, McMahon AP: Wnt-4 is a mesenchymal signal for epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney. Development 125: 4225–4234, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lin Y, Liu A, Zhang S, Ruusunen T, Kreidberg JA, Peltoketo H, Drummond I, Vainio S: Induction of ureter branching as a response to Wnt-2b signaling during early kidney organogenesis. Dev Dyn 222: 26–39, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Itaranta P, Lin Y, Perasaari J, Roel G, Destree O, Vainio S: Wnt-6 is expressed in the ureter bud and induces kidney tubule development in vitro. Genesis 32: 259–268, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carroll TJ, Park JS, Hayashi S, Majumdar A, McMahon AP: Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev Cell 9: 283–292, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yu J, Carroll TJ, Rajagopal J, Kobayashi A, Ren Q, McMahon AP: A Wnt7b-dependent pathway regulates the orientation of epithelial cell division and establishes the cortico-medullary axis of the mammalian kidney. Development 136: 161–171, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tételin S, Jones EA: Xenopus Wnt11b is identified as a potential pronephric inducer. Dev Dyn 239: 148–159, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Majumdar A, Vainio S, Kispert A, McMahon J, McMahon AP: Wnt11 and Ret/Gdnf pathways cooperate in regulating ureteric branching during metanephric kidney development. Development 130: 3175–3185, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cha SW, Tadjuidje E, Tao Q, Wylie C, Heasman J: Wnt5a and Wnt11 interact in a maternal Dkk1-regulated fashion to activate both canonical and non-canonical signaling in Xenopus axis formation. Development 135: 3719–3729, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lyons JP, Mueller UW, Ji H, Everett C, Fang X, Hsieh JC, Barth AM, McCrea PD: Wnt-4 activates the canonical beta-catenin-mediated Wnt pathway and binds Frizzled-6 CRD: Functional implications of Wnt/beta-catenin activity in kidney epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res 298: 369–387, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McNeill H: Planar cell polarity and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2104–2111, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Park TJ, Mitchell BJ, Abitua PB, Kintner C, Wallingford JB: Dishevelled controls apical docking and planar polarization of basal bodies in ciliated epithelial cells. Nat Genet 40: 871–879, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Matakatsu H, Blair SS: Interactions between Fat and Dachsous and the regulation of planar cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Development 131: 3785–3794, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Goto T, Keller R: The planar cell polarity gene strabismus regulates convergence and extension and neural fold closure in Xenopus. Dev Biol 247: 165–181, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Veeman MT, Slusarski DC, Kaykas A, Louie SH, Moon RT: Zebrafish prickle, a modulator of noncanonical Wnt/Fz signaling, regulates gastrulation movements. Curr Biol 13: 680–685, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Carreira-Barbosa F, Concha ML, Takeuchi M, Ueno N, Wilson SW, Tada M: Prickle 1 regulates cell movements during gastrulation and neuronal migration in zebrafish. Development 130: 4037–4046, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Choi SC, Han JK: Xenopus Cdc42 regulates convergent extension movements during gastrulation through Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway. Dev Biol 244: 342–357, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Heisenberg CP, Tada M, Rauch GJ, Saude L, Concha ML, Geisler R, Stemple DL, Smith JC, Wilson SW: Silberblick/Wnt11 mediates convergent extension movements during zebrafish gastrulation. Nature 405: 76–81, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kim GH, Han JK: JNK and ROKalpha function in the noncanonical Wnt/RhoA signaling pathway to regulate Xenopus convergent extension movements. Dev Dyn 232: 958–968, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Habas R, Dawid IB, He X: Coactivation of Rac and Rho by Wnt/Frizzled signaling is required for vertebrate gastrulation. Genes Dev 17: 295–309, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Habas R, Kato Y, He X: Wnt/Frizzled activation of Rho regulates vertebrate gastrulation and requires a novel Formin homology protein Daam1. Cell 107: 843–854, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tanegashima K, Zhao H, Dawid IB: WGEF activates Rho in the Wnt-PCP pathway and controls convergent extension in Xenopus gastrulation. Embo J 27: 606–617, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chhabra ES, Higgs HN: The many faces of actin: Matching assembly factors with cellular structures. Nat Cell Biol 9: 1110–1121, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Baarlink C, Brandt D, Grosse R: SnapShot: Formins. Cell 142: 172, 172.e1, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Faix J, Grosse R: Staying in shape with formins. Dev Cell 10: 693–706, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liu W, Sato A, Khadka D, Bharti R, Diaz H, Runnels LW, Habas R: Mechanism of activation of the Formin protein Daam1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 210–215, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Komiya Y, Habas R: Wnt signal transduction pathways. Organogenesis 4: 68–75, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sato A, Khadka DK, Liu W, Bharti R, Runnels LW, Dawid IB, Habas R: Profilin is an effector for Daam1 in non-canonical Wnt signaling and is required for vertebrate gastrulation. Development 133: 4219–4231, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Khadka DK, Liu W, Habas R: Non-redundant roles for Profilin2 and Profilin1 during vertebrate gastrulation. Dev Biol 332: 396–406, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nakaya MA, Habas R, Biris K, Dunty WC, Jr, Kato Y, He X, Yamaguchi TP: Identification and comparative expression analyses of Daam genes in mouse and Xenopus. Gene Expr Patterns 5: 97–105, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Stewart MD, Jang CW, Hong NW, Austin AP, Behringer RR: Dual fluorescent protein reporters for studying cell behaviors in vivo. Genesis 47: 708–717, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vize PD, Jones EA, Pfister R: Development of the Xenopus pronephric system. Dev Biol 171: 531–540, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wallingford JB, Carroll TJ, Vize PD: Precocious expression of the Wilms' tumor gene xWT1 inhibits embryonic kidney development in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol 202: 103–112, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mauch TJ, Yang G, Wright M, Smith D, Schoenwolf GC: Signals from trunk paraxial mesoderm induce pronephros formation in chick intermediate mesoderm. Dev Biol 220: 62–75, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Agrawal R, Tran U, Wessely O: The miR-30 miRNA family regulates Xenopus pronephros development and targets the transcription factor Xlim1/Lhx1. Development 136: 3927–3936, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Saka Y, Smith JC: Spatial and temporal patterns of cell division during early Xenopus embryogenesis. Dev Biol 229: 307–318, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schreiber AM, Cai L, Brown DD: Remodeling of the intestine during metamorphosis of Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 3720–3725, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Fang X, Ji H, Kim SW, Park JI, Vaught TG, Anastasiadis PZ, Ciesiolka M, McCrea PD: Vertebrate development requires ARVCF and p120 catenins and their interplay with RhoA and Rac. J Cell Biol 165: 87–98, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Park JI, Ji H, Jun S, Gu D, Hikasa H, Li L, Sokol SY, McCrea PD: Frodo links Dishevelled to the p120-catenin/Kaiso pathway: Distinct catenin subfamilies promote Wnt signals. Dev Cell 11: 683–695, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Gu D, Sater AK, Ji H, Cho K, Clark M, Stratton SA, Barton MC, Lu Q, McCrea PD: Xenopus delta-catenin is essential in early embryogenesis and is functionally linked to cadherins and small GTPases. J Cell Sci 122: 4049–4061, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Skouloudaki K, Puetz M, Simons M, Courbard JR, Boehlke C, Hartleben B, Engel C, Moeller MJ, Englert C, Bollig F, Schafer T, Ramachandran H, Mlodzik M, Huber TB, Kuehn EW, Kim E, Kramer-Zucker A, Walz G: Scribble participates in Hippo signaling and is required for normal zebrafish pronephros development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 8579–8584, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Saulnier DM, Ghanbari H, Brandli AW: Essential function of Wnt-4 for tubulogenesis in the Xenopus pronephric kidney. Dev Biol 248: 13–28, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Iglesias DM, Hueber PA, Chu L, Campbell R, Patenaude AM, Dziarmaga AJ, Quinlan J, Mohamed O, Dufort D, Goodyer PR: Canonical WNT signaling during kidney development. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F494–F500, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Schmidt-Ott KM, Masckauchan TN, Chen X, Hirsh BJ, Sarkar A, Yang J, Paragas N, Wallace VA, Dufort D, Pavlidis P, Jagla B, Kitajewski J, Barasch J: Beta-catenin/TCF/Lef controls a differentiation-associated transcriptional program in renal epithelial progenitors. Development 134: 3177–3190, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Schedl A: Renal abnormalities and their developmental origin. Nat Rev Genet 8: 791–802, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Habas R, Dawid IB: Dishevelled and Wnt signaling: Is the nucleus the final frontier? J Biol 4: 2, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wallingford JB, Habas R: The developmental biology of Dishevelled: An enigmatic protein governing cell fate and cell polarity. Development 132: 4421–4436, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Roszko I, Sawada A, Solnica-Krezel L: Regulation of convergence and extension movements during vertebrate gastrulation by the Wnt/PCP pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol 20: 986–997, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tada M, Kai M: Noncanonical Wnt/PCP signaling during vertebrate gastrulation. Zebrafish 6: 29–40, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Dale RM, Sisson BE, Topczewski J: The emerging role of Wnt/PCP signaling in organ formation. Zebrafish 6: 9–14, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Seifert JR, Mlodzik M: Frizzled/PCP signalling: A conserved mechanism regulating cell polarity and directed motility. Nat Rev Genet 8: 126–138, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Jenny A, Mlodzik M: Planar cell polarity signaling: A common mechanism for cellular polarization. Mt Sinai J Med 73: 738–750, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Wallingford JB: Vertebrate gastrulation: Polarity genes control the matrix. Curr Biol 15: R414–R416, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Curtin JA, Quint E, Tsipouri V, Arkell RM, Cattanach B, Copp AJ, Henderson DJ, Spurr N, Stanier P, Fisher EM, Nolan PM, Steel KP, Brown SD, Gray IC, Murdoch JN: Mutation of Celsr1 disrupts planar polarity of inner ear hair cells and causes severe neural tube defects in the mouse. Curr Biol 13: 1129–1133, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Montcouquiol M, Rachel RA, Lanford PJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kelley MW: Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature 423: 173–177, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Montcouquiol M, Sans N, Huss D, Kach J, Dickman JD, Forge A, Rachel RA, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Bogani D, Murdoch J, Warchol ME, Wenthold RJ, Kelley MW: Asymmetric localization of Vangl2 and Fz3 indicate novel mechanisms for planar cell polarity in mammals. J Neurosci 26: 5265–5275, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Wang J, Hamblet NS, Mark S, Dickinson ME, Brinkman BC, Segil N, Fraser SE, Chen P, Wallingford JB, Wynshaw-Boris A: Dishevelled genes mediate a conserved mammalian PCP pathway to regulate convergent extension during neurulation. Development 133: 1767–1778, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wang J, Mark S, Zhang X, Qian D, Yoo SJ, Radde-Gallwitz K, Zhang Y, Lin X, Collazo A, Wynshaw-Boris A, Chen P: Regulation of polarized extension and planar cell polarity in the cochlea by the vertebrate PCP pathway. Nat Genet 37: 980–985, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wang Y, Guo N, Nathans J: The role of Frizzled3 and Frizzled6 in neural tube closure and in the planar polarity of inner-ear sensory hair cells. J Neurosci 26: 2147–2156, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Qian D, Jones C, Rzadzinska A, Mark S, Zhang X, Steel KP, Dai X, Chen P: Wnt5a functions in planar cell polarity regulation in mice. Dev Biol 306: 121–133, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Etheridge SL, Ray S, Li S, Hamblet NS, Lijam N, Tsang M, Greer J, Kardos N, Wang J, Sussman DJ, Chen P, Wynshaw-Boris A: Murine dishevelled 3 functions in redundant pathways with dishevelled 1 and 2 in normal cardiac outflow tract, cochlea, and neural tube development. PLoS Genet 4: e1000259, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Sive HL, Grainger RM, Harland RM: Early Development of Xenopus laevis: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 103. Brand M, Granato M, Nusslein-Volhard C: Keeping and raising zebrafish, Oxford, NY, Oxford University Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF: Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn 203: 253–310, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Kloc M, Etkin LD: Analysis of localized RNA in Xenopus oocytes. In: Advances in Molecular Biology: Comparative Methods Approach to Study of Oocytes and Embryos, edited by Richter JD. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999, pp 256–278 [Google Scholar]

- 106. Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J: Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin): A Systematical and Chronological Survey of the Development from the Fertilized Egg Till the End of Metamorphosis, New York, Garland Publishing, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kim SW, Fang X, Ji H, Paulson AF, Daniel JM, Ciesiolka M, van Roy F, McCrea PD: Isolation and characterization of XKaiso, a transcriptional repressor that associates with the catenin Xp120(ctn) in Xenopus laevis. J Biol Chem 277: 8202–8208, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Barnett MW, Old RW, Jones EA: Neural induction and patterning by fibroblast growth factor, notochord and somite tissue in Xenopus. Dev Growth Differ 40: 47–57, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Taira M, Jamrich M, Good PJ, Dawid IB: The LIM domain-containing homeo box gene Xlim-1 is expressed specifically in the organizer region of Xenopus gastrula embryos. Genes Dev 6: 356–366, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Carroll TJ, Vize PD: Synergism between Pax-8 and lim-1 in embryonic kidney development. Dev Biol 214: 46–59, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. von Strandmann EP, Nastos A, Holewa B, Senkel S, Weber H, Ryffel GU: Patterning the expression of a tissue-specific transcription factor in embryogenesis: HNF1 alpha gene activation during Xenopus development. Mech Dev 64: 7–17, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Gerth VE, Zhou X, Vize PD: Nephrin expression and three-dimensional morphogenesis of the Xenopus pronephric glomus. Dev Dyn 233: 1131–1139, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Vize PD: The chloride conductance channel ClC-K is a specific marker for the Xenopus pronephric distal tubule and duct. Gene Expr Patterns 3: 347–350, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Zhou X, Vize PD: Proximo-distal specialization of epithelial transport processes within the Xenopus pronephric kidney tubules. Dev Biol 271: 322–338, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Eid SR, Brandli AW: Xenopus Na,K-ATPase: Primary sequence of the beta2 subunit and in situ localization of alpha1, beta1, and gamma expression during pronephric kidney development. Differentiation 68: 115–125, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Harland RM: In situ hybridization: An improved whole-mount method for Xenopus embryos. Methods Cell Biol 36: 685–695, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Moody SA: Fates of the blastomeres of the 16-cell stage Xenopus embryo. Dev Biol 119: 560–578, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Moody SA: Fates of the blastomeres of the 32-cell-stage Xenopus embryo. Dev Biol 122: 300–319, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Strehlow D, Heinrich G, Gilbert W: The fates of the blastomeres of the 16-cell zebrafish embryo. Development 120: 1791–1798, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Seufert DW, Brennan HC, DeGuire J, Jones EA, Vize PD: Developmental basis of pronephric defects in Xenopus body plan phenotypes. Dev Biol 215: 233–242, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Kintner CR, Brockes JP: Monoclonal antibodies identify blastemal cells derived from dedifferentiating limb regeneration. Nature 308: 67–69, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Drummond IA, Majumdar A, Hentschel H, Elger M, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, Neuhauss SC, Stemple DL, Zwartkruis F, Rangini Z, Driever W, Fishman MC: Early development of the zebrafish pronephros and analysis of mutations affecting pronephric function. Development 125: 4655–4667, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Takeyasu K, Tamkun MM, Renaud KJ, Fambrough DM: Ouabain-sensitive (Na+ + K+)-ATPase activity expressed in mouse L cells by transfection with DNA encoding the alpha-subunit of an avian sodium pump. J Biol Chem 263: 4347–4354, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Mayor R, Morgan R, Sargent MG: Induction of the prospective neural crest of Xenopus. Development 121: 767–777, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]